Abstract

Data from a large cross-sectional sample of wild chimpanzee mother-infant dyads yields evidence that young chimpanzees’ pant grunting unfolds nonlinearly over the early developmental period. Though infants begin pant grunting early, and mothers’ rates did not decrease, infant pant grunting declined as infants aged through infancy. Mother-infant dyadic pant grunting discordance therefore increased over infancy, with some discordance observed at even the earliest ages. In half of 90 observed instances involving infants ranging in age from 2 weeks to 69 months, only one member of the mother-infant dyad pant grunted; infants’ pant grunting was neither influenced by their mother’s age, their position on their mother’s body at the time of the greeting, nor the dominance status of the male greeted. Male infants were more likely to pant grunt than female infants. We discuss the developmental trend in the context of infants’ increasing independence, changing social motivations, and maledominated social hierarchy.

Keywords: chimpanzee, infant, vocal behavior, dominance, development

Introduction

Wild chimpanzees live in a socially complex world, marked by shifting dominance hierarchies, frequent inter- and intra-group aggression, long-term kin relationships, and cooperation that occurs in the contexts of short-term coalitions, long-term alliances, meat sharing, and territorial boundary patrols [Goodall 1986; Mitani 2009]. They live in large intergenerational communities, in which males remain in their natal groups and females disperse when reaching sexual maturity. Chimpanzees spend the majority of their time socializing, grooming, feeding, and resting in close proximity with others. As they do so, they utilize several calls to develop and maintain social relationships, one of the most important of which is the pant grunt used to signal subordinance [e.g., Goodall 1968; Marler and Tenaza 1977; Noë et al. 1980].

Pant grunts are one of the most frequently emitted calls in the chimpanzee vocal repertoire [Bygott 1979, Sakamaki 2011]. This call is a formal signal of submission, given by lower-ranking chimpanzees to higher-ranking individuals [see Foerster et al 2016]. Human researchers use observations of pant grunts to evaluate dominance rank relationships between chimpanzees, and the animals themselves undoubtedly use such knowledge when giving calls and responding to them. Virtually all females are subordinate to adult males, so females predictably give pant grunts to males (though see Laporte & Zuberbuhler, 2010 for discussion of flexibility). Females pant grunt to each other infrequently, though when they do so, calls are given up the hierarchy [de Waal 1982]. In contrast, exchanges between adult or adolescent males are heard often, providing rich and ever-changing information regarding chimpanzees’ acknowledgment of their relative status. Failure to acknowledge another’s higher status may trigger that individual’s aggression to affirm his position; ignorance of how to use pant grunts therefore carries a cost (see Nishida et al. 1995 and Watts 2004, for descriptions of possible gang-retaliation for hierarchy violation; see also Wilson et al. 2014).

These dyadic greetings are not only directly relevant to the pair, but also provide chimpanzee onlookers with information about the current dominance hierarchy. Such information could be useful in many contexts, including deciding who to challenge in fights and when to attempt mating with females. It would therefore be quite useful for pant grunts to be understood and given early in development. Because pant grunts reflect the sometimes subtle social hierarchy, it is apparent that some sort of learning or training is taking place. Although pant grunts are given frequently in adulthood (see above), few data exist regarding the development and acquisition of the call [see Hayaki 1990]. Goodall (1986) and Hiraiwa-Hasegawa (1989) placed the early emergence of the true pant grunt to conspecifics at about 3–4 months. Plooij (1984) described socially directed grunting somewhat earlier, around 2 months of age, while Marler (1976) noted a relative absence of the call in wild infants). Bard (2003), observing captive chimpanzees, recorded calls within the first few weeks. In contrast, Jacobsen and colleagues (1932) did not record pant grunts until after the second month. In these cases, pant grunts were given to human caretakers, suggesting infants may learn the vocalization as a generalized greeting rather than one elicited by a conspecific.

Infants learn the pant grunt while they are in physical contact with their mothers. Mothers carry infants <1 year ventrally, with the infants clinging belly-to-belly. By about 7 months of age, infants also ride dorsally on their mother’s back, jockey-style. By 18 months of age, riding is predominantly dorsal. Infants 3 years or younger are rarely outside their mother’s arm reach and, when mothers are traveling or climbing, they are still carried (sometimes for several years longer); the two remain in close visual contact up to about 5 years old [van Lawick-Goodall 1968, Lonsdorf et al 2014]. Of relevance to the current work, infants riding dorsally share their mother’s view of encountered individuals; infants riding ventrally typically do not. Infants riding ventrally do, though, have their chests against their mother’s chest, and may therefore receive tactile information about her vocalizations in addition to visual and auditory information. It would be useful to distinguish among simple mimicry, some kind of arousal-based contagion, and a “true” pant grunting based on recognition of a newly-arrived other’s higher status. Available data make the first two difficult to distinguish (though mother-infant concordance rates are useful, see also Laporte and Zuberbuhler 2011), but for the third it is possible that infant positional information could yield insight.

Previous work [Laporte & Zuberbuhler, 2011] investigated pant grunt use from early infancy through adulthood, presenting initial evidence for a possible U shaped developmental curve. Utilizing a mixed longitudinal/cross-sectional design, they reported that the call was used at higher rates in early infancy, declined in late infancy and juvenility, and rose again in adolescence. Data for their target developmental period were collected from a sample of 14 infants and juveniles (<6.5 years). A large chimpanzee community at Ngogo in Kibale National Park, Uganda, in contrast, offers an opportunity to add to the scant data record. Here we report observations of 37 infants in the same developmental period, providing a more detailed and focused examination of the period during which a decline in pant-grunting occurs.

In this paper, we address several questions: How commonly do infants give pant grunts? How concordant are mother-infant pairs? Does the infant’s age affect the likelihood of greeting? Does the infant’s physical position vis a vis the mother, or the dominance status (high, low, medium) of the greeted male, impact likelihood of greeting? Because females immigrate into a community at adolescence (and thus young mothers have far less social experience than older mothers), does maternal age impact infants’ greeting behavior? We also investigate sex differences in call usage.

Method

We conducted observations at Ngogo in Kibale National Park, Uganda, during 5 months from July to December 2016. During this time, we observed 37 infants ranging in age from 2 weeks to 69 months (mean = 26 months). In total, 90 observations were recorded from 35 different mothers and 30 different greeted males (Table 1). During this study, only once was a female observed to be the target of a greeting (a 4-month old male greeted 20-year old Carson; for simplicity, we henceforth refer to all targets as male). For 83 of these observations, data on the infant’s specific position at the time of the greeting were recorded; in 66 of these 83 cases, infant and mother were in physical contact with each other at the time of the greeting. Infant position was recorded as either “dorsal” (i.e. riding on the mother’s back) or “ventral” (i.e. clinging to her abdomen). There were 4 cases in which the infant had slid somewhat off the mother’s back and was hanging so that their sides were pressed together. These cases were counted as dorsal.

Table 1.

Chimpanzee study subjects (mother-infant dyads and male greeted) with names, ages, and ranks

| Mother | Mother Age (yrs) | Infant Age (mos) | Infant Name | Male Age | Male Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amelia | 22 | 11 | noname | 17 | low |

| Anderson | 42 | 55 | Amina | 15 | low |

| Bartoli | 32 | 20 | Herzog | 43 | high |

| Beecher | 15 | 10 | Vigilant | 33 | high |

| Beryl | 14 | 9 | noname | 14 | low |

| Binoche | 24 | 15 | Sufjan | 50 | mid |

| Carson | 20 | 34 | Rosalind | 17 | low |

| Cate | 15 | 5 | Lady Muraski | 26 | mid |

| Cecilia | 40 | 61 | Joya | 31 | mid |

| Christine | 17 | 35 | Nadine | 39 | low |

| Dahlia | 23 | 48 | Septima | 19 | low |

| Fitzgerald | 47 | 44 | Pilar | 20 | mid |

| Geraldyn | 20 | 24 | Tubman | 27 | low |

| Hester | 15 | 0.5 | noname | 39 | mid |

| Ingrid | 22 | 21 | Varda | 22 | high |

| Jolie | 28 | 1 | Kabacwezi | 25 | high |

| 68 | Zawinul | 17 | low | ||

| Julianne | 38 | 6 | noname | 34 | high |

| Kidman | 39 | 44 | Cedar | 44 | mid |

| Kundry | 44 | 42 | Mandela | 32 | high |

| Leigh | 15 | 30 | Lombard | 27 | mid |

| Leonora | 39 | 56 | Sandino | 54 | low |

| Lita | 48 | 15 | M. Ali | 10 | low |

| Natalie | 18 | 11 | Lumumba | 21 | mid |

| Penelope | 25 | 5 | Chimamanda | 22 | mid |

| Rusalka | 26 | 59 | Flanagan | 29 | mid |

| Sabin | 18 | 41 | Nina | 29 | high |

| Sarah | 40 | 51 | Salonen | 30 | mid |

| Senta | 34 | 4 | Junot | 20 | low |

| 66 | Struhsaker | 17 | low | ||

| Shire | 18 | 46 | Rodriguez | ||

| Sigourney | 40 | 60 | Fricka | ||

| Sills | 50 | 19 | Denis | ||

| Stella | 21 | 30 | Anarkali | ||

| Sutherland | 54 | 69 | Naidu | ||

| Taylor | 25 | 0.5 | noname | ||

| Wangari | 20 | 6 | Biko | ||

ages listed here were at first observation (in data analysis, ages included were those at each observation)

Criteria for data point inclusion were the following: (1) infant and mother must be traveling or resting together, no more than 3 meters apart at the moment of encountering the male (2) at least one of the mother-infant dyad must give a pant grunt greeting (3) both the mother and the male encountered must be identifiable by name (in the four instances where a group of males was the target of the greeting, the highest-ranking male’s data were used) and (4) mother’s and infant’s face must be simultaneously visible at the moment of the greeting. Simply hearing, or failing to hear, a greeting was not sufficient.

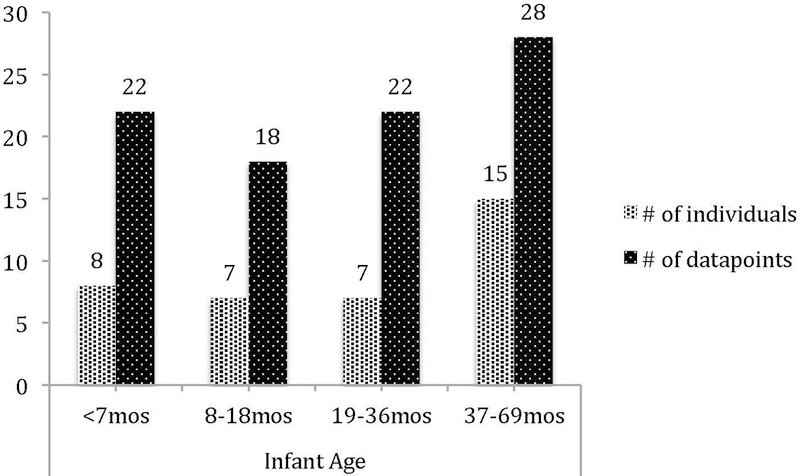

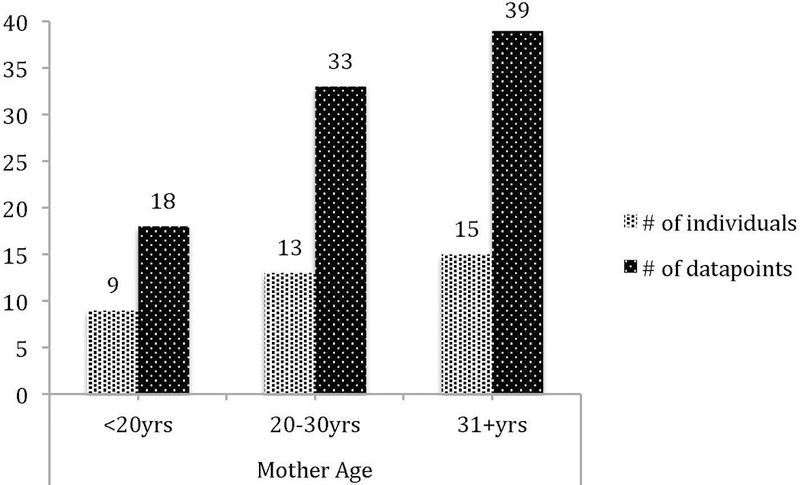

For the purposes of analyzing developmental change, infant chimpanzees were categorized into 4 age groups, based on those used in the previous literature, and consistent with locomotor development [e.g., Hiraiwa-Hasegawa 1989; Matsumoto 2017; Plooij 1984; Sarringhaus et al. 2016]: <7 months, 8–18 months, 19–36 months, and 37–69 months. Note that 25 of 37 dyads contributed more than one data point. Figure 1 provides counts for both individuals and data points. On average, each dyad contributed 2.4 cases to the dataset (median = 2). For purposes of analyzing potential relevance of mothers’ status, adult females were categorized into three groups: <20 years (young/primiparous), 20–30 years (middle aged), and 31+ years (mature). Figure 2 shows counts for both individuals and data points. We conceptualize infant age as both a continuous (weeks of age) and a categorical (4 age classes) variable; the continuous measure served to ensure that findings (or lack thereof) were not due to classifying infants into age-class groupings.

Fig. 1.

Count of infant chimpanzees (and total datapoints contributed) by age class

Fig. 2.

Count of mother chimpanzees (and total datapoints contributed) by age class

Several particularities of data collection deserve description. First, our focus was infants’ and juveniles’ greetings within the dyad - if either executed the pant grunt, the data were included. Since at least one member of the dyad must have pant grunted for the observation to be recorded, “negative” data were not included; this avoided recording as “failure to greet” females who had recently greeted that male outside the researcher’s view and were simply shifting position. Thus, base rates of greetings in this sample are not calculable. Our fourth inclusion criterion, in which faces must be visible, ensured inclusion of instances in which young infants’ voices were so quiet that, while the greeting was obvious from the shape of the infant’s mouth, it was not clearly audible from the researcher’s vantage point. Laporte and Zuberbuhler (2011) note too, that, due to the effort required to produce an audible pant grunt, infants may sometimes be seen to form the greeting with their mouth even in the absence of an audible sound. Relatively few infant pant grunts were recorded in this way (i.e., seen but not heard); their inclusion demonstrates our focus on the development of attempt/motivation and not specifically skill in execution.

Results

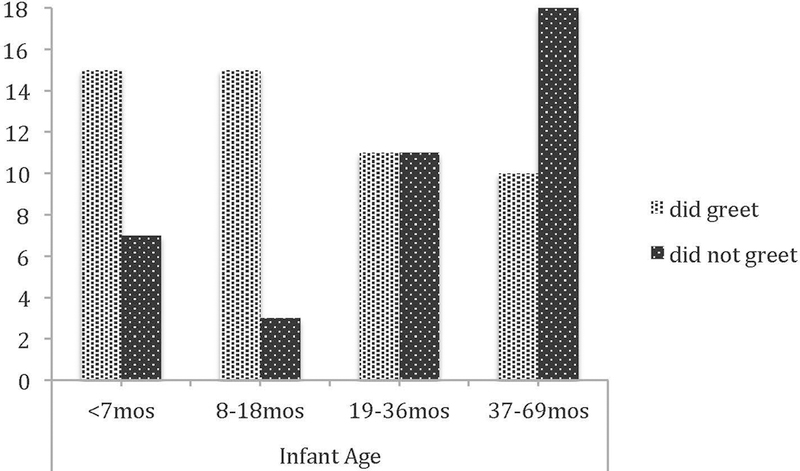

Infant chimpanzees’ greeting behavior varied based on their age. Infant age at instances of greeting (mean=81 wks) was significantly younger than infant age at instances of failure-to-greet (when mother did, mean=135 wks; t(69.26) = 3.27, p=0.002). Chi-square analysis demonstrated a significant effect of age on greeting (X2 = 11.06, p=0.011; Figure 3). The percentage of greetings (vs. silence) in each age class were: <7 months (15/22, 68.2%), 8–18 months (15/18, 83.3%), 19–36 months (1½2, 50%), and 37–69 months (10/28, 36%). This age-based pattern also emerges when infants are analyzed separately by sex (and with age in months as a continuous variable): t(36) = 2.48, p=.018 and t(45) = 1.95, p=.057 for males and females, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Infant chimpanzee pant grunting counts, by age class

Maternal age (in years) was unrelated to whether infants greeted or not (t(89) = 0.94, p=0.35). Infants of young mothers greeted others 72% of the time, and infants of middle aged and mature mothers pant grunted to conspecifics 52% and 54% of the time, respectively. Mothers’ age class did not affect their infants’ greeting behavior (X2 = 2.26, p=0.32). Conversely, when infant age was treated as a continuous variable (age in months), mothers with older infants did greet more (t(8.69) = −2.33, p=0.045). With so few cases in which mothers did not greet (7 total), we are cautious in interpreting these results.

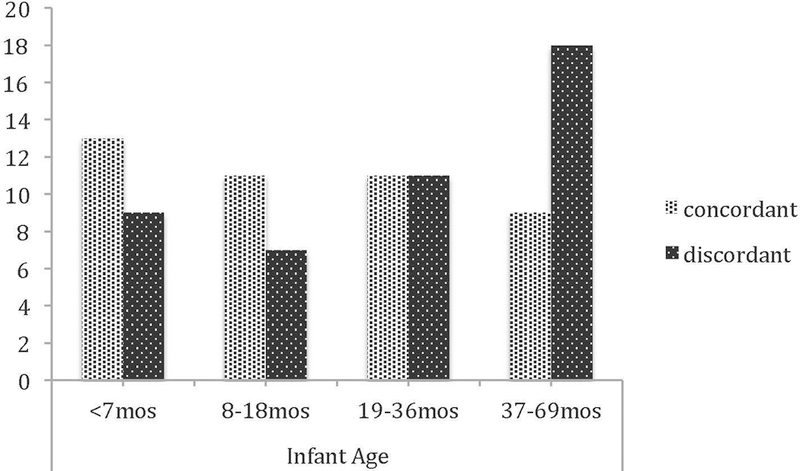

A mother’s likelihood of greeting males did not differ as a function of her age in years, t(88)=−0.520, p=0.604; if infants greet less as they get older, concordance rates within the dyad should fall as infants age. In concordant dyads, infants were indeed younger (m=21mos, n=44) than in discordant dyads (m=31mos, n=46; t(84.98) = 2.40, p=0.019). When age is treated as a categorical variable, dyadic concordance rates appeared to decrease as infants aged, but this apparent pattern was not significant (X2 = 4.61, p=0.203; Figure 4). Concordance rates of mother-infant greetings in each infant age class were: <7 months (13/22, 59%), 8–18 months (11/18, 61%), 19–36 months (1½2, 50%), and 37–69 months (9/27, 33%; see Figure 4).

Fig. 4.

Dyadic concordance for pant grunting, by infant age class

Of the cases in which the dyad was discordant due to a mother giving a pant grunt while her infant remained silent, 18 of 39 of these (46%) comprised infants in the oldest age group (older than 3 years). When the dyad was discordant due to an infant pant grunting while his or her mother remained silent, only 1 of 7 (14%) comprised infants in that oldest group. In sum, decreasing dyadic concordance with infant age seemed primarily due to infants’ silence, not to the mothers’.

Infants’ position on their mother (dorsal vs. ventral) appeared unrelated to their pant grunt behavior (analyses included only those 66 cases in which mother and infant were physically in contact at the time of the greeting). Infants riding dorsally greeted others in 54% of cases (14/26), while those riding ventrally did so in 68% of cases (27/40).Chi-square analysis did not reveal a significant effect of position on greeting (X2 = 1.25, p=0.26). If we exclude those 4 cases in which the mother did not produce a pant grunt, results remain insignificant (X2= 0.63, p=0.43).

Infants’ greeting behavior did not vary based on the dominance status of the adult male being greeted. Infants were no more likely to greet high ranking males than medium- or lower-ranking ones: X2 = 5.15, p=0.076. Finally, infant males were more likely to greet than were infant females: male (23/33 instances = 70%) and females (21 of 47 instances = 45%; X2 = 4.90, p=0.027). This could not be accounted for by infant age - males were no older or younger than females: t(83)=−.296, p=.768.

Discussion

Data from a robust cross-sectional sample of wild-living chimpanzees yields evidence that young chimpanzees’ pant grunting unfolds nonlinearly over the early developmental period. Though infants begin pant grunting early (the earliest instance we observed was an approximately 10-day old neonate), rate of infant pant grunting is lower by at about 3 years of age, at a time when our data suggest mothers actually show higher rates of their own pant grunting. This difference does not reflect convergence on an adult pattern (pant grunting is again well-utilized in adolescence, e.g., Laporte & Zuberbuhler 2011; Sandel et al 2017); rather, this may be a feature of this developmental stage. Mother-infant dyadic concordance for pant grunting was higher when infants were younger, though some discordance was observed at even the earliest ages. While analyses treating age as both a continuous and categorical variable revealed the same trend, categorical analysis did not reach statistical significance perhaps due to small sample size. Of a total of 90 observed instances, in 46 (50%) only one member of the dyad pant grunted; infants’ pant grunting rates were neither influenced by their mother’s age nor the dominance status of the male greeted.

In 39 cases (43% of observations), a mother pant grunted and her infant did not. In only seven instances (two from the same dyad) was the reverse true. These seven warrant individual consideration, see Table 2 (note that only one of these instances involved a high-ranking male). Two mothers (Beryl and Cate) were the youngest, and the only primiparous females in this subsample; of these, one (Beryl) was a recent immigrant. Cate did greet on another occasion (alpha male Jackson), and Beryl greeted three other males ranging in age from 19–43 yrs over the course of study. The other seven mothers in this youngest age class greeted males consistently each time. In the cases of Juliane (failed to greet early adolescent male PeeWee) and Senta (failed to greet female Carson), it is arguable that the infants’ greetings were anomalous, and not due to their mothers’ lack of greeting. Binoche’s failure to greet two different males, including one of the oldest in the community, is curious; these are Binoche’s only two contributions to the data record. While it is possible that these seven cases were instances of “effort” or “food” grunts [Plooij 1984], and not intended as a greeting, in each of these cases it was the researcher’s sense that the target was a male (and in one case, a large female). These seven cases in which mothers failed to greet could be due to infant “error,” in which (1) the mother had recently greeted the same male out of sight of the human observer and appropriately avoided a “re-greet” or (2) the infant, but not the more savvy mother, “over-greets”, as appeared to be the case with Juliane and Senta. It is also possible that the human observer failed to see the mother’s greeting.

Table 2.

Dyads in which mothers failed to pant grunt with their ages and male ranks

| Mother | Mother Age | Offspring Age | Male | Male Age | Male Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binoche | 24 yrs | 15 mos | Peterson | 21 | mid |

| (+2mos) | Brownface | 50 | mid | ||

| Kundry | 44 yrs | 42 mos | Jackson | 25 | 1 (alpha) |

| Juliane | 38 yrs | 6 mos | PeeWee | 10 | low |

| Senta | 34 yrs | 4 mos | Carson (female) | 20 | n/a |

| Beryl | 14 yrs | 9 mos | Porkpie | 22 | mid |

| Cate | 15 yrs | 9 mos | Garrett | 27 | low |

The unanticipated finding that young males greeted more than young females suggests an avenue for future investigation. This does not appear to be an artifact of individual infants being overrepresented in the data, such that an infant’s internal consistency might sway the data: three of the five infants contributing the most observations were male, and their likelihood of greeting ranged from 50% to 83% (mean=71%) in this subsample of five. One interesting possibility is that males prioritize attention to hierarchical signals early, given the large and important role it will play in their adolescent and adult lives. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that this should emerge early in males and be of less importance to females, to whom explicit recognition of intricacies of dominance hierarchies are less central to social life (and less varied, as essentially all females greet all adult males).

A recent report on a related question - the social context of pant grunting across the lifespan - showed onset at about 2 months of age rising to a peak at about 7 months of age, a subsequent decline in production through juvenility, and a rise again in early adolescence [Laporte & Zuberbuhler 2011]. Our observations of 37 infants similarly reveal a clear decline in pant grunting as infants age. Since young chimpanzees are not increasingly spatially, and therefore socially, separate from their mothers until their third year or so (and not fully weaned until their sixth, see Matsumoto, 2017), it is interesting that the pant grunt emerges so early at all. The literature suggests a developmental primacy to social vocalizations, and not merely triggered contagion - food grunting, for example, seems to emerge somewhat later. Laporte and Zuberbuhler (2011) suggest that infants who engage in this activity may be less likely to fall victim to infanticide by group members, concluding that “chimpanzee babies were keen to acknowledge the presence of any group member with a grunt, regardless of their identity...” (p. 1129). In our own sample, infants in the youngest age group (those at greatest risk for in-group infanticide, which does occur at Ngogo (Goodall 1986; Nishida 2012; Townsend et al 2007) greeted almost twice as often the oldest (68% vs 37%). That said, there is reason to doubt that infants are pant grunting in a direct attempt to fend off aggression, as adult males in the community are not typically aggressive to babes-in-arms and about half of infanticides are perpetrated by adult females (Wilson et al 2014), who are infrequently greeted by infants. Mature males do, however, often display aggression to adolescent males and females, who are frequent targets despite their enthusiastic displays of subordinance. This is not to say that greeting may not be an inborn reflex, selected for over time in the context of high rates of inter-individual aggression (or even as a trigger for maternal guarding, though young infants are very rarely out of their mother’s arm reach), as a precursor to species-typical adult behavior. Or, as Plooij (1984) noted in his observation of young infants, miscategorization of a startled uh-grunt elicited by sudden maternal pant grunt. Even so, dyadic concordance was not 100% in even the youngest age group observed, and the apparent lower rate in pant grunting by about three years of age remains unexplained.

It is difficult to argue that infants older than three are big enough to withstand aggression, and it is challenging to conceptualize a mechanism that would code for early behavior, then halt it, then begin it again. One possibility is that as infants age they (1) are more likely to encounter greeting situations distinct from their mothers’ due to physical separation from her and (2) exhibit different greeting behavior in these two situations. In such a scenario, the current inclusion criteria (recording only greeting events from mother-infant dyads) would not capture older infants’ behavior when away from their mothers. If this differed from that with their mother (if, for example, infants greeted when away, but not with for some reason) we would be underreporting these greetings in this age group. In this case, however, these older infants would still be proportionately less likely to greet, which remains a developmental phenomenon in need of explanation. We propose three alternatives for further consideration.

First, there may be some proximate social or ecological pressure, specific to the “preschooler” developmental stage, that inhibits pant grunt greeting. This stage marks increasing independence (both social and physical) from one’s mother, and perhaps repercussions for inaccurate or inappropriate greetings are greater than sanctions for not greeting at all. Mature males show tolerance for young infants’ exuberance, but this declines when infants are around three [van Lawick-Goodall 1968], at which point their misbehavior is more likely to result in a hitting or threatening response. This may enforce a “watch and learn” strategy that facilitates entry into a complex social hierarchy that must be individually learned; such a strategy may keep young chimps socially (and safely) sidelined until skills are learned or needed. The “watch and learn” approach may work well until juveniles approach reproductive age, at which point the balance shifts.

Second, it may be useful to consider the contributions of dynamic systems theory [e.g. Thelen & Smith 2006] to understand developing asynchronies or “regressions.” There are several well-studied examples of seeming “loss” of motor skills by human infants that can be meaningfully explained as dynamic system reorganizations during transitional periods. For example, infants return to the developmentally earlier, more “primitive” two-arm reaching during the transition to upright walking [Corbetta & Bojczyk 2002]. In this case, the balance and mobility pressure on infants as they learn to walk cause them to pair their arm movements - until the system stabilizes again, the locomotor benefit from synchronizing one’s arms temporarily alters previously- learned competencies. Such explanations are a reminder that all behaviors need not have been “selected for”, but may instead reflect myriad systems (social, behavioral, vocal, locomotor) self-organizing as they multi-directionally affect one another during periods of disequilibrium. Such “disequilibrium” may in fact characterize young chimpanzees in their fourth year, as they transition from mother-care to selfcare - locomoting and socializing autonomously for the first time. Young chimpanzees between 3–6 years spend a large proportion of their independent time with their peers (rather than non-maternal adults), and several new challenges may call for reprioritization of motor and vocal skill acquisition. In adult chimpanzees, greeting behavior involves a suite of vocal, behavioral, and postural cues, the sophisticated integration of which likely presents a substantial challenge for the young learner. Longitudinal, individualized data tracking the relation between greeting behavior and proportion of daily time spent with different age cohorts, may be revealing here.

Third, a U-shaped developmental curve may provide an interesting analog to early human linguistic behavior, in which toddlers make fewer tense regularization errors (e.g., “goed” instead of “went”) than do preschoolers, who make more [e.g., Marcus et al. 1992]. Older children then return to a low error rate, a pattern presumed to reflect toddlers’ simple mimicry of those around them, preschoolers’ attempts to discern and apply grammar rules (albeit incorrectly), and older children’s acceptance (and memorization) of irregulars. We do not suggest that chimpanzees’ greeting vocalizations are akin to human language - it is simply interesting to consider examples of mimicry as a “placeholder” precursor to more sophisticated social behavior. Laporte and Zuberbuhler (2011) make a related observation that “the lack of use [during the preschool years] was not the result of incompetence but could be explained with changes in motivation.” (p1230) The “watch and learn” strategy described above is one potential mechanism, made available to infants by an age- related increase in cognitive and behavioral control.

The current evidence confirms an early emergence of pant grunting and subsequent lower production over the infancy developmental period, beginning about 3 years of age. This difference is independent of mothers’ pant grunting, which remains steady regardless of infant age. Infants’ pant grunting did not vary based on the status of the male encountered, but male infants were more likely to pant grunt than female infants. Individual variation in infant pant grunting, through longitudinal investigation, might offer insight into the function of this greeting during prepubertal development. Situational, motivational, and maturational factors contributing to the spontaneous decrease (or suppression) of pant grunting in the late infancy period remain to be investigated more closely; these have the potential to illuminate the role of learned behavior in the intensely social world of wild chimpanzees.

Acknowledgements:

Our field research was sponsored by the Ugandan Wildlife Authority, Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the Makerere University Biological Field Station. We thank Samuel Angedakin, Rachna Reddy, and David Watts for logistical support and help in the field. This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grant RO1AG049395, and the Bard Research Fund. The authors state that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Bard K (2003). Development of emotional expressions in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) In Emotions inside out: 130 years after Darwin’s the expression of the emotions in man and animals (Ekman P, Campos J, Davidson R, de Waal F, eds.), pp 88–90. New York Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bygott J (1979). Agonistic behavior, dominance, and social structure in wild chimpanzees of the Gombe National Park In The Great Apes (Humburg D, McCown E, eds.), pp 405–427. Benjamin/Cummings, California. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta D, Bojczyk K (2002). Infants return to two-handed reaching when they are learning to walk. Journal of Motor Behavior 34:83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal F (1982). Chimpanzee politics. Harper & Row, New York [Google Scholar]

- Foerster S, Franz M, Murray C, Gilby I, Feldblum J, Walker K, Pusey A (2016). Chimpanzee females queue but males compete for social status. Scientific Reports 6:35404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J (1986). The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of behavior. Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J (1968). The behaviour of free-living chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve. Animal Behavior Monographs 1:161–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hayaki H (1990). Social context of pant-grunting in young chimpanzees In The chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains: Sexual and life history strategies (Nishida T, ed.), pp 189–206. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- Hiraiwa-Hasegawa M (1989). Sex differences in the behavioral development of chimpanzees at Mahale In Understanding chimpanzees (Heltne P, Marquardt L, eds.), pp 104–115. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen C, Jacobsen M, Yoshioka J (1932). Development of an infant chimpanzee during her first year. John Hopkins Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte M, Zuberbuhler K (2010). Vocal greeting behavior in wild chimpanzee females. Animal Behavior 80:467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte M, Zuberbuhler K (2011). The development of a greeting signal in wild chimpanzees. Developmental Science 14:1220–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdorf E, Markham A, Heintz M, Anderson K, Ciuk D, Goodall J, Murray C (2014). Sex differences in wild chimpanzee behavior emerge during infancy. PLoS ONE e99099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus G, Pinker S, Ullman M, Hollander M, Rosen T, Xu F (1992). Overregularization in language acquisition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 57:1–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marler P (1976). Social organization, communication, and graded signals: The chimpanzee and the gorilla In Growing points in ethology (Bateson P, Hinde R, eds.), pp 239–280. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Marler P, Tenaza R (1977). Signaling behavior of apes with special reference to vocalization In How animals communicate (Sebeok T, ed.), pp 965–1033. Indiana University Press, London, [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T (2017). Developmental changes in feeding behaviors of infant chimpanzees at Mahale, Tanzania: Implications for nutritional independence long before cessation of nipple contact. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 163:356–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani J (2009). Cooperation and competition in chimpanzees: Current understanding and future challenges. Evolutionary Anthropology 18:215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T (2012). Chimpanzees of the lakeshore. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Hosaka K, Nakamura M, Hamai M (1995). A within-group gang attack on a young adult male chimpanzee: Ostracism of an ill-mannered member? Primates 36: 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nishie H, Nakamura M (2017). A newborn infant chimpanzee snatched and cannibalized immediately after birth: Implications for “maternity leave” in wild chimpanzee. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 165:194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noë R, de Waal F, van Hooff J (1980). Types of dominance in a chimpanzee colony. Folia Primatologica 34:90–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plooij F (1984). The behavioral development of free-living chimpanzee babies and infants In Monographs on infancy (Lipsitt L, ed.). Ablex Publishing Corp., Norwood, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel A, Reddy R, Mitani J (2017) Adolescent male chimpanzees do not form a dominance hierarchy with their peers. Primates 58:39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamaki T (2011). Submissive pant-grunt greeting of female chimpanzees in Mahale Mountain National Park, Tanzania. African Study Mongraphs 32:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sarringhaus L, MacLatchy L, Mitani J (2016) Long bone cross-sectional properties reflect changes in locomotor behavior in developing chimpanzees. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 160:16–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E, Smith L (2006). Dynamic systems theories In Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development, 6th ed (Lerner R, Damon W, eds.), pp 258–312. Wiley & Sons Inc, [Google Scholar]

- Townsend S, Slocombe K, Thompson M, Zuberbuhler K (2007). Female-led infanticide in wild chimpanzees. Current Biology 17:355–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lawick-Goodall J (1968). A preliminary report on expressive movements and communication in the Gombe Stream chimpanzees In Primates. studies in adaptation and variability (Jay P, ed.), pp 313–374. Holt, Rhinehart & Winston, NY. [Google Scholar]

- van Lawick-Goodall J (1968). The behavior of free-living chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve In Animal Behavior Monographs (Cullen J, Beer C, eds.). Bailliere, Tindall, & Cassell, London. [Google Scholar]

- Watts D (2004). Intracommunity coalitionary killing of an adult male chimpanzee at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. International Journal of Primatology 25:507–521. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M, Boesch C, Fruth B, Furuichi T, Gilby I, Hashimoto C, Hobaiter C, Hohmann G, Itoh N, Koops K, Lloyd J, Matsuzawa T, Mitani J, Myungu D, Morgan D, Muller M, Mundry R, Nakamura M, Pruetz J, Pusey A, Riedel J, Sanz C, Schel A, Simmons N, Waller M, Watts D, White F, Wittig R, Zuberbuhler K, Wrangham R (2014). Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts. Nature 513:414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]