Abstract

Background

In 2016, Medicare implemented the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model (CJR), a national mandatory bundled payment model for lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR) in randomly selected metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). Hospitals in selected MSAs receive bonuses or pay penalties based on LEJR spending through 90 days post-discharge.

Methods

We conducted difference-in-differences analyses using Medicare claims from 2015–2017, comparing LEJR episodes in 75 MSAs randomized to mandatory participation in CJR (treatment MSAs) with episodes in 121 control MSAs, before vs. after CJR implementation. Our primary outcomes were institutional spending per LEJR episode (primarily hospital and post-acute facility payments), rates of post-surgical complications, and the proportion of patients with higher spending risk (a measure of patient selection). Analyses adjusted for hospital of admission and beneficiary and procedure characteristics.

Results

In 2015–2017 there were 280,161 LEJR procedures in 803 hospitals in treatment MSAs and 377,278 procedures in 962 hospitals in control MSAs. After CJR initiation, institutional spending per LEJR episode declined more in treatment than in control MSAs (differential change: -$812 or −3.1% relative to the treatment group baseline; p<0.001). The differential reduction was driven largely by a 5.9% relative decrease in the fraction of episodes with any institutional post-acute care. The program had no effect on complication rates (p=0.67) or the fraction of LEJR procedures performed on higher-risk patients (p=0.81).

Conclusions

In its first 18 months, the CJR program resulted in a modest reduction in spending per LEJR episode, before accounting for program bonuses and penalties, without increasing complication rates

INTRODUCTION

In April 2016, Medicare initiated the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model (CJR), a mandatory bundled payment model for inpatient lower extremity joint replacements (LEJR) of the hip and knee.1 In the CJR program, hospitals are held accountable for spending for an episode of care composed of the index hospitalization for the LEJR procedure and all spending (with minor exceptions specified by CMS) in the 90 days following discharge.2 In contrast to the voluntary nature of other alternative payment models, CJR randomized metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) to mandatory participation.3,4 Hospitals in MSAs randomized to the CJR program were subject to bundled payments for all LEJR episodes.

Like other bundled payment programs,5,6 CJR was designed to provide financial incentives for hospitals to reduce spending without compromising quality across an entire episode of care after discharge. During a CJR episode, fee-for-service payments are made as usual to all providers (e.g., outpatient physicians or skilled nursing facilities). Participating hospitals then undergo an annual retrospective reconciliation process in which their average spending per episode is compared to a hospital-specific benchmark. Hospitals share savings with Medicare if spending falls below the benchmark or, starting in 2017, pay a penalty if spending exceeds the target.1,2 Like Medicare’s accountable care organization programs,7,8 hospitals’ savings or losses are adjusted based on performance on a mix of LEJR quality measures such as complication rates.

Voluntary bundled payment programs have been associated with either unchanged or reduced spending without deterioration in quality.9–11 However, changes observed in these programs could be due to the selective participation of highly motivated hospitals and providers.12,13 CJR is an important advance on prior voluntary programs because it features both a randomized design and mandatory participation. Evaluations of the first year of CJR found modest decreases in total spending, though not always statistically significant, without changes in quality.14,15 As CJR matures it is unclear whether these savings become larger and whether negative unintended consequences, such as hospitals avoiding sicker, potentially costly patients,12,13 become evident.

We compared changes in spending and quality in the first two years of the CJR program between MSAs randomized to the new bundled payment model (treatment MSAs) and control MSAs. We also examined for any potentially unintended consequences such as the selection of healthier patients for LEJR, increased volume, or changes in coding practices to receive higher target prices.

METHODS

Study Population

We analyzed Medicare claims and enrollment data from 2015–2017 for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with inpatient primary LEJR procedures (diagnosis-related group [DRG] 469 or 470 at discharge) at hospitals in one of the 196 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) eligible for participation in the CJR program (inclusion flow diagram in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Revisions or replacements of prior LEJR procedures were not included in CJR. The unit of analysis was the LEJR episode, defined as the time period between the date of admission for the hospitalization and 90 days post-discharge.

The CJR program began in April 2016. Our 12-month pre-intervention period included procedures performed between January 1 through December 31, 2015, and our 15-month post-intervention period included procedures occurring July 1, 2016 through September 30, 2017. We used data through December 31, 2017 to cover the 90-day period after hospital discharge for all LEJRs, which encompasses the time period used by CJR to assess performance in years 1 and 2 of the program. We excluded episodes that began during a six-month transition period from January 1 through June 30, 2016, as during this time LEJR episodes overlap into the post-intervention period or occurred early after initiation when hospitals may have been adjusting to the new payment model.

For each beneficiary with an LEJR procedure, we included the first LEJR admission with or without fractures from 2015–2017. We excluded episodes for patients with active end-stage renal disease or for episodes with any additional LEJR procedures (e.g. sequential knee replacements) in the 90 days after discharge from the initial procedure. We also excluded LEJR procedures performed in hospitals participating in the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) program for LEJR procedures,16 and any LEJR episode where the patient was discharged to a skilled nursing facility or home health agency participating in the BPCI program for LEJR.

We applied one additional exclusion criterion not part of CJR: to assess patient risk and ensure we captured all care within the episode, we limited our analyses to beneficiaries with continuous enrollment in fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B for 12 months prior to their LEJR episode through 90 days after discharge or until death (comparison of overall Medicare population and continuous enrolled population in Table S1).

Study Variables

CJR Exposure

Of 380 MSAs nationally, 196 were identified as eligible for the CJR program based on LEJR volume and BPCI participation (Appendix Methods A in the Supplementary Appendix). Medicare categorized the 196 eligible MSAs into strata based on median population (2 strata) and quartile of pre-intervention LEJR episode spending (4 strata) for a total of 8 strata. Within each stratum, Medicare then randomized MSAs to treatment or control groups, with higher probabilities of treatment assignment in the higher-spending strata. To address potential bias from regression to the mean that would otherwise result from the oversampling within higher-spending strata, we weighted MSAs to equalize the probability of treatment assignment within each of the 8 strata (Appendix Methods A).

The initial randomization was announced by Medicare in July 2015,2 but in November 2015, Medicare cut the number of MSAs randomized to the intervention from 75 to 67, largely due to updates in hospital participation in BPCI (Appendix Methods A). Because these cuts were not random, we conducted an intent-to-treat analysis based on the initial randomization, where all LEJR episodes performed in hospitals in the initially randomized 75 MSAs composed the treatment population.

Patient, Hospital, and Procedure Characteristics

From Medicare enrollment files, we assessed patients’ age, sex, race, rural/urban categorization of their ZIP code of residence,17 original reason for Medicare enrollment (i.e., disability vs. age), Medicaid enrollment, and the presence of 27 chronic conditions from the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse.18 For each LEJR episode, we assessed the type of procedure (hip or knee replacement and total or partial replacement), DRG, and whether there was a hip fracture.

Primary Outcomes

Our first primary outcome was institutional spending, which included payments to a hospital (inpatient or outpatient), post-acute care, hospice and durable medical equipment spending (further details in Appendix Methods B). We chose institutional spending as a primary outcome because it makes up approximately 85% of all spending in LEJR episodes, it is the component of spending where prior LEJR bundled payment demonstrations have shown savings, 9,19 and non-institutional spending (payments to physicians and other providers, ambulance, independent laboratories) was only available for a 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries (additional details in Table S2). Our measures of spending focused only on reimbursements to providers and did not account for bonuses or penalties applied during the CJR annual reconciliation process.

Our second primary outcome was a composite LEJR complications measure developed and used by Medicare for public reporting20 which defines a complication as any of several medical (e.g. pulmonary embolism) or surgical complications (e.g. joint infection) during or within 90 days after the admission date (full details in Appendix Methods B). We included all cases in this quality measure.

Our third primary outcome was the proportion of patients receiving LEJR procedures who were at elevated risk for higher spending. Under CJR, hospitals have a financial incentive to selectively avoid sicker, higher-cost patients because the CJR program does not adjust each hospital’s benchmark for patient factors other than the presence of a hip fracture.21 We estimated each patients’ burden of illness for each LEJR episode by estimating a “risk score” based on predicted episode spending. Risk scores were estimated using a linear regression model predicting total episode spending fitted with pre-intervention 2013–2014 data incorporating patient characteristics (Appendix Methods C). Using this model, we assigned each episode to a quartile of risk score and assessed the proportion of LEJR procedures performed on patients in the highest quartile.

Secondary Outcomes

We examined several secondary outcomes (detailed in Appendix Methods B). Using claims for a 20% random sample of beneficiaries, we measured total Medicare spending per LEJR episode. Utilization measures included use of post-acute care by facility type, length of stay in post-acute facilities, and readmission or emergency department visits within 90 days of discharge. We also measured 90-day mortality and a complication measure that excluded hip fractures, as used by Medicare for public reporting. We examined differential changes in the DRG used for LEJR episodes (469 or 470), mean risk score, sociodemographic characteristics, and presence of chronic comorbidities. To assess the contribution of differential changes in observable patient characteristics to our estimates, we also compared results of our primary analysis with and without adjustment for patient and episode characteristics.

Statistical Analysis

Difference-in-differences Analysis

Our primary analysis was a difference-in-differences approach. We fit a linear regression model at the LEJR episode-level patient and procedure characteristics (described in Appendix Methods D) as well as hospital and MSA random effects to control for time-invariant differences between treatment and control hospitals and MSAs, as well as indicators for each quarter of our study period (see Appendix Methods D). The key variable in the model was an interaction between the post-intervention period and an indicator for the LEJR being performed in a treatment MSA, which describes the average differential change in the outcome for episodes in treatment MSAs relative to those in control MSAs (i.e. the estimated effect of the CJR program). In a pre-specified alternative modelling approach, we used hospital fixed effects with robust variance estimators at the MSA level (Appendix Methods D). In sensitivity analyses, we examined generalized linear models with a log link and mean proportional to variance function for continuous outcomes and logistic regression models for binary outcomes. Finally, in post-hoc analyses, we also compared outcomes in 3 six-month periods from April-September 2016, October 2016-March 2017 and April-September 2017 (Appendix Methods D).

There were no differences in the pre-intervention trends between the treatment and control MSAs for each outcome in 2015, the pre-period used in our models (Table S3). Because 2015 is a single year, we also compared pre-intervention trends over a longer time period (2011–2015) in a post-hoc analysis (more details provided in Appendix Methods E).

To adjust for multiple testing, we set the significance level for each of the three primary outcomes at P <0.0167 (0.05/3). We provide 95% confidence intervals, without p values, for exploratory estimates of secondary outcomes, which were not adjusted for multiple testing.

Our analytic protocol was pre-specified and is available online.22

RESULTS

Study Population

From 2015–2017, there were 280,161 LEJR procedures in 826 hospitals in treatment MSAs and 377,278 procedures in 990 hospitals in control MSAs (unweighted). In the treatment MSAs, 7% of LEJR procedures were performed in the 8 MSAs excluded after randomization. In 2015, before the intervention, there were differences between patients in treatment vs. control MSAs; for example, 11.4% of LEJR episodes were for Medicaid eligible patients in the treatment group, vs. 10.3% in the control MSAs (Table 1). Meaningful differences were also present in the characteristics of hospitals and counties in treatment vs. control MSAs in 2015 (Tables S4 and S5).

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics in Treatment and Control Groups in Period Before LEJR Implementation, 2015

| Treatment MSAs | Control MSAs | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (weighted N) | 102,089 | 143,824 |

| Age (mean) | 74.5 | 74.3 |

| Male (%) | 35.9% | 36.0% |

| DRG 469 (LEJR with major complication/comorbidity, %) | 5.6% | 5.1% |

| DRG 470 (LEJR without major complication or comorbidity, %) | 94.4% | 94.9% |

| Fracture (%) | 16.2% | 15.0% |

| Total Knee Replacement (%) | 54.2% | 56.2% |

| Total Hip Replacement (%) | 31.4% | 30.9% |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 89.8% | 90.8% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5.9% | 5.6% |

| Asian | 1.0% | 0.6% |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 2.2% | 2.2% |

| Hispanic | 1.1% | 0.7% |

| Original Reason for Entitlement (%) | ||

| Age >65 | 84.2% | 84.1% |

| Disability | 15.7% | 15.8% |

| ESRD1 | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Medicaid Eligible | 11.4% | 10.3% |

| Urban Residence2 | 85.0% | 82.4% |

| Prior Inpatient Use | 20.4% | 19.7% |

| Prior Institutional Post-Acute Care | 7.7% | 7.2% |

| Number of chronic conditions3 (mean) | 7.1 | 7.0 |

Abbreviations: diagnosis related group (DRG), lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR), end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Hospital characteristics were measured using the Medicare Provider of Services and Impact files.

Patients with ESRD were excluded from the payment program. However, some patients initially qualified for Medicare due to ESRD but no longer classified as ESRD at the time of LEJR

Urban location defined using the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) code database (http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/index.php). Urban was defined as a patient residing in a “metropolitan” ZIP code. Data was missing for 0.16% of episodes which were largely located in Puerto Rico.

We assessed the presence of 27 conditions from the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW), which uses claims since 1999 to describe Medicare beneficiaries’ accumulated chronic disease burden (see Appendix Methods C for list of conditions).

Spending and Utilization

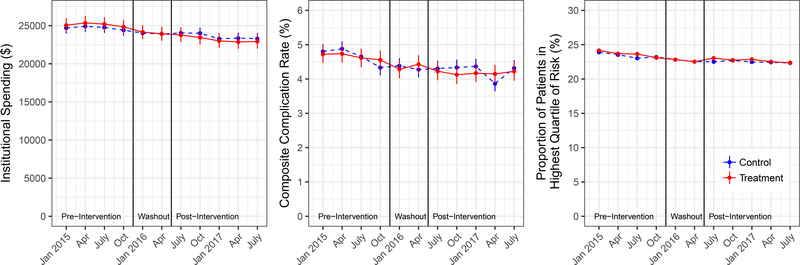

Institutional spending on LEJR episodes declined from $25,903 to $23,915 in the treatment group and from $24,596 to $22,238 in the control group (adjusted differential change of -$812, p<0.001), or a 3.1% differential decrease relative to mean pre-period spending in treatment MSAs (Figure 1 and Table 2). This decrease in institutional spending grew over the 18-month period of CJR implementation from a differential change of -$541 in April-September 2016 (95% CI −754, −328) to -$860 in April-September 2017 (95% CI −1075, −645; Table S6).

Figure 1. Adjusted Trends in Primary Outcomes, 2015–2017.

Adjusted estimates for each of the three primary outcomes by quarter from 2015–2017 for LEJR episodes in the treatment group (red solid line) vs. the control group (blue dashed line). The left panel shows trends in institutional spending, the middle shows composite complication rates and the right shows the proportion of patients in the highest quartile of risk. The solid black vertical lines mark the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods, with the January-June 2016 “washout” period in the middle (see Methods). All estimates adjust for hospital and MSA random effects. Estimates for institutional spending and complication rate also adjust for patient and episode characteristics as described in the Methods and Appendix Methods. The proportion of patients in highest risk quartile outcome does not adjust for patient or episode characteristics because these characteristics are used to generate the patient risk score, which uses coefficients estimated from 2013–2014 data.

Table 2.

Differential Change in Primary Outcomes Before and After CJR Implementation

| Treatment | Control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Period Episode Average |

Post-Period Episode Average |

Unadjusted Difference |

Pre-Period Episode Average |

Post-Period Episode Average |

Unadjusted Difference |

Adjusted Difference-in-Differences Estimate (95% CI) |

p-value | |

| Primary Outcomes | ||||||||

| Institutional Spending ($) | 25,903 | 23,915 | −1,988 | 24,596 | 23,238 | −1,358 | −812 (−981, −644) | <0.001 |

| Composite Rate of Complications | 4.72% | 4.15% | −0.6% | 4.56% | 4.00% | −0.6% | −0.04 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.67 |

| Proportion of Episodes with Top Quartile of Patient Risk | 25.30% | 23.60% | −1.69% | 23.12% | 21.62% | −1.50% | −0.1 (−0.5, 0.4) | 0.81 |

Adjusted estimates show the differential change in primary outcomes between treatment and control groups after vs. before CJR implementation. A detailed definition institutional spending is presented in the Methods and Appendix Table S1. For the complication rate, per Medicare’s approach, each episode was classified as having no complication or one or more complications. All estimates adjust for hospital and MSA random effects. Estimates for institutional spending and complication rate also adjust for patient and episode characteristics as described in the Methods and Appendix Methods. The top quartile of patient risk outcome does not adjust for patient or episode characteristics because these characteristics are used to generate the patient risk score, which uses coefficients estimated from 2013–2014 data.

The differential spending reduction was driven largely by institutional post-acute care: skilled nursing facilities (adjusted differential change: -$527, 95% CI −611, −443) and inpatient rehabilitation facilities (-$227, 95% CI −274, −180). In the 20% sample of beneficiaries, total LEJR spending (including all professional fees in addition to institutional spending) differentially decreased by $1,084 (95% CI −1409, −760), or a 3.6% differential reduction (Table 4). There was no change in the per capita volume of LEJR episodes in the treatment vs. control MSAs after CJR intervention (Table S7).

The CJR program was associated with a 2.5% percentage point (95% CI −3.0, −2.1) differential decrease (or 5.9% relative decrease) in the proportion of patients discharged to institutional post-acute care and a differential reduction in length of stay of 1.7 days in post-acute facilities among those using any institutional post-acute care (95% CI −2.0, −1.4, Table 4). Estimates were not substantively different using models with fixed effects, generalized linear models or logistic regression models for their respective outcomes (Table S8).

Quality Outcomes

The program did not have a significant differential effect on the composite complication rate (adjusted differential change in proportion of episodes with a complication: −0.04%; p=0.67; Figure 1 and Table 2). In sensitivity analyses excluding hip fracture admissions, results were similar (−0.05%, 95% CI −0.2, 0.1, Table 3). The program had no significant negative effect on post-discharge hospital utilization (inpatient, ED or observation stay) or mortality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differential Change in Spending and Quality Outcomes Before and After CJR Implementation

| Treatment | Control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Period Episode Average |

Post-Period Episode Average |

Unadjusted Difference |

Pre-Period Episode Average |

Post-Period Episode Average |

Unadjusted Difference |

Adjusted Difference-in-Differences Estimate |

95% CIa | |

| Spending Outcomes ($) | ||||||||

| Total Spending (20% sample) b | 30,504 | 27,950 | −2,554 | 28,836 | 27,193 | −1,643 | −1,084 | −1409 ,−760 |

| Index Hospitalization | 14,733 | 14,605 | −128 | 14,326 | 14,086 | −241 | −67 | −179 ,44 |

| Other Inpatient (e.g. Readmissions) | 1,514 | 1,481 | −33 | 1,395 | 1,390 | −5 | −22 | −88 ,45 |

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 5,252 | 3,898 | −1,355 | 4,587 | 3,787 | −801 | −527 | −611 ,−443 |

| Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility | 1,261 | 877 | −384 | 1,201 | 1,030 | −171 | −227 | −274 ,−180 |

| Long Term Care Hospital | 86 | 56 | −30 | 113 | 76 | −37 | 9 | −13 ,30 |

| Home Health Agency | 2,056 | 1,988 | −68 | 1,963 | 1,857 | −106 | −4 | −22 ,14 |

| Hospice | 68 | 72 | 4 | 63 | 69 | 6 | 0 | −8 ,8 |

| Outpatient Facility c | 792 | 831 | 40 | 811 | 833 | 22 | 22 | 2 ,42 |

| Professional Services (20% Sample) | 4,182 | 4,125 | −57 | 4,017 | 3,975 | −42 | −37 | −93 ,18 |

| Durable Medical Equipment | 141 | 107 | −34 | 138 | 111 | −27 | −5 | −10 ,1 |

| Hospital and Post Acute Care (PAC) Utilization | ||||||||

| Index Hospitalization LOS, Days (mean) | 4.15 | 3.81 | −0.3 | 4.04 | 3.72 | −0.3 | −0.02 | −0.04 ,−0.004 |

| Discharged to Institutional PAC (%)d | 42.2% | 31.6% | −10.6% | 41.3% | 33.1% | −8.1% | −2.5 | −3.0 ,−2.1 |

| Discharged to Home Health Agency (HHA) (%) | 34.6% | 38.5% | 3.8% | 33.0% | 33.9% | 0.9% | 2.5 | 2.0, 2.9 |

| Institutional PAC LOS, Days (mean) e | 22.65 | 20.62 | −2.0 | 21.13 | 20.67 | −0.5 | −1.7 | −2.0 ,−1.4 |

| Non-IRF Institutional PAC LOS, Days (mean) e | 23.44 | 20.79 | −2.7 | 21.71 | 21.06 | −0.7 | −2.1 | −2.4 ,−1.8 |

| HHA Number of Episodes (mean) | 12.74 | 11.55 | −1.2 | 12.76 | 12.47 | −0.3 | −0.9 | −1.0 ,−0.8 |

| Composite Complication Rate and Mortality | ||||||||

| Medicare Defined Complications (No Fractures, %)f | 2.4% | 2.2% | −0.2% | 2.5% | 2.2% | −0.3% | −0.05 | −0.2 ,0.1 |

| 90 Day Mortality (%) | 2.6% | 2.2% | −0.4% | 2.3% | 2.1% | −0.1% | −0.06 | −0.2 ,0.1 |

| Post Discharge Hospital Use (90-Day Rates) | ||||||||

| All Cause Inpatient Readmission | 9.7% | 9.1% | −0.6% | 9.2% | 9.5% | 0.3% | −0.6 | −0.9 ,−0.2 |

| Emergency Department (ED) without Admission | 13.5% | 13.7% | 0.2% | 13.8% | 13.9% | 0.2% | 0.3 | −0.1 ,0.7 |

| Observation Stay without Admission | 2.1% | 2.2% | 0.1% | 2.3% | 2.4% | 0.05% | 0.05 | −0.1 ,0.2 |

| Any ED/Observation/Inpatient Visit | 22.1% | 21.6% | −0.5% | 21.8% | 22.2% | 0.3% | −0.3 | −0.8 ,0.1 |

Abbreviations: 95% confidence interval (95% CI), emergency department (ED), home health agency (HHA), inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR), length of stay (LOS), post-acute care (PAC).

Adjusted estimates show the differential change in secondary outcomes between treatment and control groups after vs. before CJR implementation. All estimates adjust for hospital and MSA random effects as well as patient and episode characteristics as described in the Methods and Appendix Methods.

The 95% CI presented are not adjusted for multiple testing and should be interpreted cautiously as they represent exploratory analyses.

Total spending includes both institutional and non-institutional spending (Appendix Table S2), or both Medicare Part A and Part B spending. This spending estimate uses a 20% random sample of LEJR episodes because professional services spending is only available for a 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries.

Outpatient facility spending includes payments to hospitals for physician office visits, imaging or lab tests, provided in facilities attached to or affiliated with a hospital. It does not include separate payments to physicians for their services.

Institutional post-acute care (PAC) includes all inpatient post-acute care, largely skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), but also including inpatient rehabilitation facilities and long-term acute care hospitals. Institutional PAC length of stay without inpatient rehabilitation facilities was estimated because these facilities are not paid based on length of stay.

Length of stay and number of episodes estimated only among beneficiaries with any use of institutional PAC (with or without IRF use) or HHA, respectively

Risk Selection and Changes in Coding

There was no differential change in our primary outcome for patient selection, the change in the proportion of patients in the top risk score quartile (differential change −0.04%, p=0.67; Figure 1 and Table 2), or in the average patient risk score (Table S9).

In treatment MSAs, there was a differential decrease in the proportion of patients who originally entered Medicare because of disability (−0.6 percentage points or relative change of −3.8%; 95% CI −1.0, −0.2, Table S10). However, the estimated impact of the CJR program effects on episode spending was reduced by only 2.5% after adjustments for observed patient characteristics before accounting for episode characteristics (Table S11).

DISCUSSION

Through 18 months after implementation, we found that the CJR program reduced payments per LEJR episode by 3% without any significant change in rates of complications. This decrease in payments grew over an 18-month period, raising the possibility that CJR could lead to greater payment reductions as hospitals adapt to the new payment model. The 3% payment reduction does not reflect net savings to Medicare because it does not account for administrative costs, bonus or penalty payments.1,23

As one of the only payment models in Medicare implemented as a mandatory randomized trial, the CJR program is a unique experiment in payment reform. CJR’s mandatory participation generated significant controversy, culminating in the Trump Administration transitioning the program to a partly voluntary model as of March 2018.24 Though the future of mandatory payment models is uncertain, the CJR program helps address the question of whether savings seen in prior bundled payment demonstrations were due to the select nature of the hospitals that volunteered. Our findings suggest that the changes observed in voluntary programs may be echoed in mandatory programs.

The decreased spending in CJR participating hospitals came nearly exclusively from reductions in the use of inpatient post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. This is not surprising because post-acute care represents a large and highly variable fraction of spending in episodes25,26 and hospitals have strong financial incentives to reduce the frequency of institutional post-acute care. We found no negative impact on complications, readmissions, or mortality under CJR; therefore, it appears hospitals may have successfully identified patients at the margin of needing institutional post-acute care who could instead be safely discharged home with home health services. However, our measures of quality do not include important patient-centered measures such as functional status, pain and overall satisfaction. There may be a negative impact on these dimensions of quality that we do not observe.

Our results are consistent with prior evidence that savings in bundled payment models9,14,15,19,25,27 and other alternative payment models28,29 have been concentrated in changing post-acute care use. Post-acute care may represent the easiest target for hospitals to decrease episode-level spending because it is often unclear when post-acute care is beneficial or what intensity of post-acute care is optimal.30–32

One concern with current bundled payment programs is that they create a financial incentive to avoid sicker, more costly patients. There has been inconsistent evidence on risk selection in prior evaluations of voluntary bundling and CJR.9,33 While we did not see any substantive changes in our primary risk selection outcome, we found evidence of differential reductions in treatment MSAs in the proportion of patients undergoing LEJRs who were disabled. Adjustment for these and other observable patient characteristics had a minor effect on our estimates of savings. However, we could not examine whether changes in other unobserved risk factors for high post-surgical spending may have contributed to our results. Close monitoring for risk selection under the CJR program is warranted.

Our study has several limitations. Our conclusions on the impact of bundled payments may not generalize beyond LEJR procedures34 and our evaluation only covers the first 2 years of the program. However, because CJR transitioned to a partly voluntary model 3 months after the end of our study period, our evaluation encompasses all but two months when the model was mandatory. Our evaluation focused on payments from Medicare and did not assess the overall financial impact to hospitals. Finally, our estimate of savings may be an underestimate of the true impact of bundled payments because we included LEJR episodes performed in 8 MSAs (accounting for 7% of treatment episodes) originally randomized to participate in CJR but then subsequently excluded.

In conclusion, we found that mandatory bundled payment models for joint replacement led to modest decreases in spending per episode driven by lower use of institutional post-acute care, without any significant change in complications in the first two years of the CJR program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from The Commonwealth Fund (AW, AM, AME, KJM), National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (K23 AG058806, MLB and P01 AG032952, JMM).

Contributor Information

Michael L. Barnett, Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston MA; Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Andrew Wilcock, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

J. Michael Mc Williams, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Arnold M. Epstein, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Karen E. Joynt Maddox, Department of Internal Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

E. John Orav, Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston MA; Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

David C. Grabowski, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Ateev Mehrotra, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation; (Accessed Oct 9, 2016 at https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicare Program; Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Payment Model for Acute Care Hospitals Furnishing Lower Extremity Joint Replacement Services. Fed. Regist 2015;(Accessed Apr 18, 2017 at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/07/14/2015-17190/medicare-program-comprehensive-care-for-joint-replacement-payment-model-for-acute-care-hospitals) [PubMed]

- 3.Mechanic RE. Mandatory Medicare Bundled Payment — Is It Ready for Prime Time? N Engl J Med 2015;373(14):1291–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Maddox KEJ. The Rise and Fall of Mandatory Cardiac Bundled Payments. JAMA 2018;319(4):335–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter ME, Thomas H. Lee MD. The Strategy That Will Fix Health Care. Harv. Bus. Rev 2013;(Accessed Aug 28, 2017 at https://hbr.org/2013/10/the-strategy-that-will-fix-health-care) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Press MJ, Rajkumar R, Conway PH. Medicare’s New Bundled Payments: Design, Strategy, and Evolution. JAMA 2016;315(2):131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Next Generation ACO Model | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation; (Accessed Mar 15, 2017 at https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Next-Generation-ACO-Model/) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; Medicare Shared Savings Program: Accountable Care Organizations. Final rule. Fed Regist 2015;80(110):32691–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association Between Hospital Participation in a Medicare Bundled Payment Initiative and Payments and Quality Outcomes for Lower Extremity Joint Replacement Episodes. JAMA 2016;316(12):1267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Lena M., Ryan Andrew M., Shih Terry, Thumma Jyothi R., Dimick Justin B. Medicare’s Acute Care Episode Demonstration: Effects of Bundled Payments on Costs and Quality of Surgical Care. Health Serv Res 2017;53(2):632–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation; (Accessed Oct 9, 2016 at https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ACE/) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher ES. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Program for Joint Replacement: Promise and Peril? JAMA 2016;316(12):1262–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pronovost PJ, Miller J, Newman-Toker DE, Ishii L, Wu AW. We should measure what matters in bundled payment programs. Ann Intern Med 2018;(Accessed at + 10.7326/M17-2815) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelstein A, Ji Y, Mahoney N, Skinner J. Mandatory Medicare Bundled Payment Program for Lower Extremity Joint Replacement and Discharge to Institutional Postacute Care: Interim Analysis of the First Year of a 5-Year Randomized Trial. JAMA 2018;320(9):892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Lewin Group. CMS Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model: Performance Year 1 Evaluation Report. 2018;(Accessed Sep 5, 2018 at https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/cjr-firstannrpt.pdf)

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation; (Accessed Oct 9, 2016 at https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrill R, Cromartie J, Hart G. Rural-Urban Commuting Code Database. (Accessed Jun 29, 2018 at http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/index.php)

- 18.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. 2014;(Accessed Mar 25, 2015 at https://www.ccwdata.org/)

- 19.Navathe AS, Troxel AB, Liao JM, et al. Cost of Joint Replacement Using Bundled Payment Models. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(2):214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Complication Rate for Hip/Knee Replacement Patients. (Accessed May 21, 2018 at https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/Data/Surgical-Complications-Hip-Knee.html)

- 21.HealthPayerIntelligence. CMS Bundled Payment Models Lead to Greater Patient Selectivity. HealthPayerIntelligence; 2017;(Accessed May 22, 2018 at https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/cms-bundled-payment-models-lead-to-greater-patient-selectivity) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnett ML. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Program Evaluation. Open Sci. Framew 2018;(Accessed May 18, 2018 at https://osf.io/2pdtf/) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navathe AS, Liao JM, Shah Y, et al. Characteristics of Hospitals Earning Savings in the First Year of Mandatory Bundled Payment for Hip and Knee Surgery. JAMA 2018;319(9):930–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services 7500 Security Boulevard Baltimore. CMS finalizes changes to the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model, cancels Episode Payment Models and Cardiac Rehabilitation Incentive Payment Model. 2018;(Accessed May 17, 2018 at https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2017-Press-releases-items/2017-11-30.html)

- 25.Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Wild RC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Initiative: Most Hospitals Are Focused On A Few High-Volume Conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(3):371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huckfeldt PJ, Mehrotra A, Hussey PS. The Relative Importance of Post‐Acute Care and Readmissions for Post‐Discharge Spending. Health Serv Res 2016;51(5):1919–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jubelt LE, Goldfeld KS, Chung W, Blecker SB, Horwitz LI. Changes in Discharge Location and Readmission Rates Under Medicare Bundled Payment. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(1):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in Postacute Care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. JAMA Intern Med 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early Performance of Accountable Care Organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med 2016;374(24):2357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kane RL. Finding the Right Level of Posthospital Care: “We Didn’t Realize There Was Any Other Option for Him.” JAMA 2011;305(3):284–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoverman C, Shugarman LR, Saliba D, Buntin MB. Use of postacute care by nursing home residents hospitalized for stroke or hip fracture: how prevalent and to what end? J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56(8):1490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buntin MB, Colla CH, Deb P, Sood N, Escarce JJ. Medicare spending and outcomes after postacute care for stroke and hip fracture. Med Care 2010;48(9):776–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navathe AS, Liao JM, Dykstra SE, et al. Association of Hospital Participation in a Medicare Bundled Payment Program With Volume and Case Mix of Lower Extremity Joint Replacement Episodes. JAMA 2018;320(9):901–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Evaluation of Medicare’s Bundled Payments Initiative for Medical Conditions. N Engl J Med 2018;379(3):260–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.