Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the effect of sperm concentration adjustment in human ejaculates on the sperm DNA quality and longevity.

Methods

Semen samples were obtained from 30 donors with a normal spermiogram. Following centrifugation, the sperm pellet was resuspended in PBS, and the sperm concentration adjusted to 200, 100, 50, 25, 12, and 6 × 106/mL. Each set of samples was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the sperm DNA damage was assessed using the chromatin-dispersion test following 0 h, 2 h, 6 h, and 24 h of incubation.

Results

Sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) did not differ between the selected experimental conditions at T0; however, Kaplan–Meier estimates for survival showed significant differences with respect to the dilution and time (all P values were smaller than .001). DNA fragmentation in semen samples adjusted to 200 × 106/mL was approximately 3.3 times higher when compared to samples containing 25 × 106/mL and 3.9 higher in comparison with samples adjusted to 12 × 106/mL following 2 h of in vitro incubation. Although there was evidence of individual variation in SDF during the incubation period, the general finding was that lower sperm concentrations resulted in a slower rate of DNA fragmentation.

Conclusions

Incubation of spermatozoa for ART purposes should be done following a concentration adjustment below 25 × 106/mL in order to avoid a higher susceptibility of the sperm DNA molecule towards fragmentation.

Keywords: Sperm DNA fragmentation, Sperm concentration, Fertility, Male factor

Introduction

When different human ejaculates are compared, one of the main variations observed is the large fluctuation existing in the sperm count [1]. Such differences are even larger, but stable within a determined range, when different mammalian species are compared [2]. This reflects that, under natural conditions, the reproductive strategies associated to any species are highly sperm-concentration dependent; however, a tolerance for the sperm count in the ejaculate does exist within each species. Nevertheless, assisted reproduction techniques (ARTs) have challenged this biological rule, and high sperm concentration, associated to normal individuals, is no longer required for a successful reproductive outcome. For example, in bulls, the sperm concentration in a neat ejaculate is averaged on 400 × 106, while commercial straws for insemination purposes are usually adjusted to 20 × 106/mL spermatozoa [3, 4] or even less than 5 × 106/mL when sex-sorted sperm is used [5].

Successful artificial insemination (AI) relies on the delivery of a sufficient and effective number of spermatozoa into the female reproductive tract. However, low number of spermatozoa used for insemination must be compensated with sperm characteristics such as acceptable motility, normal morphology, stable membranes, and the ability to undergo acrosome reaction and above all, spermatozoa must have good DNA quality in order to successfully participate in syngamy producing an orthodox and stable 2n zygote [6, 7]. In fact, in the era of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), sperm DNA integrity has become increasingly more important to achieve pregnancy rather than the number of spermatozoa present in the ejaculate. In contrast, when other reproductive strategies such IVF or intrauterine insemination (IUI) are used for fertilization, larger quantities of spermatozoa are still mandatory [8], but the quality control of DNA is not excluded.

Most clinical studies still address sperm DNA integrity as a static property, providing information concerning the amount of spermatozoa with DNA damage at a determined time moment, which is usually associated with the ejaculation-collection time. It must be however emphasized that DNA, like any other vital biomolecule present in the spermatozoon, tends to accumulate damage proportionately to the increasing time of exposure to in vitro conditions [9–11]. As such, the loss of sperm fertilizing ability may be directly associated with such dynamic growth of DNA damage in relation to the time of in vitro semen exposure [10]. To emphasize on such DNA longevity, we have previously established the rate of sperm DNA fragmentation (r-SDF) defined as the increment of SDF in a specific time unit (generally hours), when spermatozoa are exposed to the in vitro environment under specific experimental conditions [7, 11].

Using ram as an experimental model, we have demonstrated that lower sperm concentrations may result in a slower r-SDF [12]. Rams usually present an extremely high sperm concentration when compared with other species [13, 14], but we found that reducing this concentration to values between 12 and 6 million spermatozoa per milliliter leads to a stabilization of SDF, while also increasing the relative sperm DNA longevity. Because these findings may have important implications for in vitro manipulation of ejaculates used for ARTs and given that advanced reproductive procedures tend to use sperm at low concentrations, the aim of this study was to analyze the effect of sperm concentration on the sperm DNA integrity. For this purpose, we designed an experiment where sperm DNA longevity was dependent on two different variables, incubation time and sperm concentration, when the samples were exposed to equivalent experimental conditions.

Material and methods

Semen samples for this study were obtained from 30 healthy donors (age of 28.5 ± 2.0 years) during the spring and summer of 2017. All subjects had to accomplish the criteria for semen quality as per the WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen (concentration ≥ 15 million/mL, motility ≥ 40%, morphology ≥ 4%, Endtz-negative) [15]. All subjects provided an informed consent to use the sample for the purposes of the experiments. All specimens were collected following 3 days of abstinence and left to liquefy for 30 min. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min and the seminal plasma was discarded. The resulting sperm pellet was resuspended in PBS (Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Six different aliquots from each sample where adjusted to final concentrations of 200, 100, 50, 25, 12, and 6 million/mL.

An aliquot of each sample was rapidly subjected to an initial SDF assessment which was considered as SDF-T0. Furthermore, to evaluate the sperm DNA longevity, we calculated the rate of SDF (r-SDF) of each sample incubated at 37 °C and ambient atmosphere for 24 h following 2 h (SDF-T2), 6 h (SDF-T6), and 24 h (SDF-T24) of incubation. The r-SDF was defined as the increase in SDF per time unit (h). The periods of evaluation considered were r-SDF T0–2, r-SDF T2–6, and r-SDF T6–24.

Sperm DNA fragmentation was assessed using Dynhalosperm® (Halotech DNA, Madrid, Spain). Tubes containing aliquots of low-melting point agarose were placed in a water bath at 90–100 °C for 5 min to fuse the agarose, and subsequently transferred to an incubator at 37 °C. After 5 min of incubation, 20 μL of the sample was mixed with the fused agarose. Twenty microliters of the semen-agarose mix was pipetted onto slides pre-coated with agarose and covered with a 20 × 20-mm coverslip. The slides were then placed on a cold plate at 4 °C for 5 min to allow the agarose to turn into a microgel with the spermatozoa embedded within. The coverslips were gently removed, and the slides immediately immersed horizontally into an acid solution for 7 min. Subsequently, the slides were placed into a lysis solution for 20 min. After washing in distilled water for 5 min, the slides were dehydrated in 70% and 100% ethanol for 2 min each and finally air-dried.

All slides were stained using SYBR Green (2 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) in VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and a minimum of 300 spermatozoa per sample were scored using an Epifluorescence Leica DMI6000 microscope using a dry ×40 fluorite magnification objective (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

All data were analyzed using the SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) program. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare SDF as well as r-SDF in specific time frames. To determine if the final concentration affected the dynamics of SDF over time, survival curves using the Kaplan–Meier analysis were created, reporting newly fragmented sperm DNA cells that appeared following each incubation time. The curves were compared using a log-rank test. To normalize the data, the background SDF was subtracted from each incubation time, thus producing a common starting survival value of 100% survival. The level of significance was set as P < 0.05.

Results

Static assessment

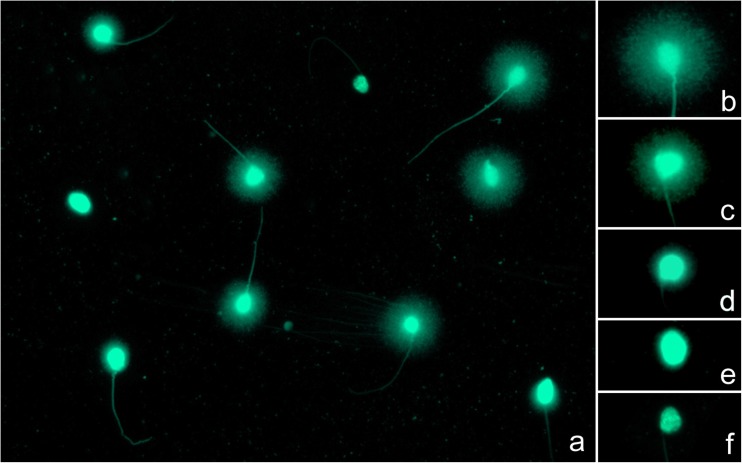

Following the chromatin dispersion test, spermatozoa without DNA fragmentation exhibited haloes of chromatin emerging from the nuclear core, while these haloes appeared small or completely absent in cells positive for DNA fragmentation (Fig. 1). A special, highly affected subgroup of spermatozoa, called degraded sperm, could be easily recognized as the nuclear core appears irregularly or faintly stained. Sperm DNA fragmentation increased over the time of incubation, independently of the final sperm concentration used in our experiment.

Fig. 1.

Interpretation of the SCD procedure (a). Spermatozoa without DNA fragmentation show haloes of chromatin around a compact core (b, c), whereas such haloes appear small (d) or absent (e) in cells containing fragmented DNA. In case of degraded spermatozoa, the nuclear core appears irregularly or faintly stained (f)

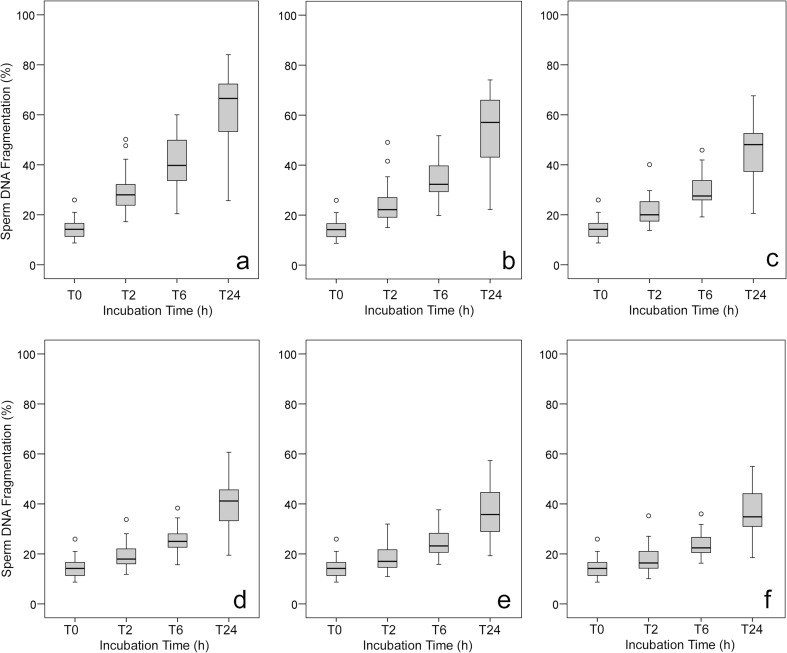

The net results of SDF assessed at different time frames are shown in Fig. 2 while results from the comparative analysis of SDF between the experimental groups are shown in Table 1. SDF values at T0 were obtained using sperm samples once the sperm was liquefied and centrifuged and the seminal plasma was removed. These values are common for all the experimental conditions depending on the sperm concentration.

Fig. 2.

a-f Box and Whisker diagram showing the distribution of sperm DNA fragmentation. Values observed in samples containing 200 × 106 (a), 100 × 106 (b), 50 × 106 (c), 25 × 106 (d), 12 × 106 (e), and 6 × 106 (f) spermatozoa per mL

Table 1.

Long-rank Matel–Cox and chi-square comparative analysis of SDF between the experimental groups

| Concentration | 200 × 106/mL | 100 × 106/mL | 50 × 106/mL | 25 × 106/mL | 12 × 106/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 × 106/mL |

χ2 = 93.8 P 0.000 |

||||

| 50 × 106/mL |

χ2 = 357.7 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 87.7 P 0.000 |

|||

| 25 × 106/mL |

χ2 = 710.7 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 299.6 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 64.2 P 0.000 |

||

| 12 × 106/mL |

χ2 = 858.2 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 402; P 0.000 |

χ2 = 64.3 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 8 P 0.000 |

|

| 6 × 106/mL |

χ2 = 913.5 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 441.9 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 139.9 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 14.9 P 0.000 |

χ2 = 1.0 P 0.300 |

Dynamic assessment

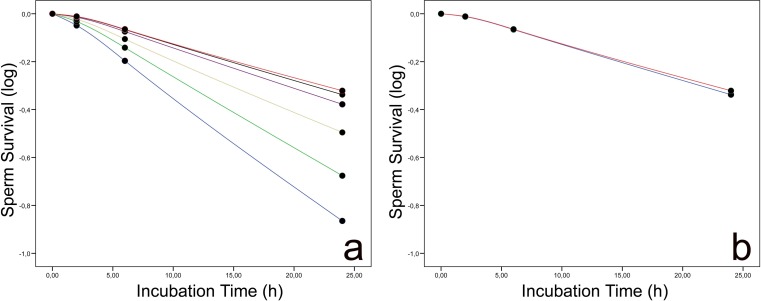

Following in vitro incubation, the % SDF increased in a time-dependent manner in all experimental groups. Sperm incubation in the presence of 200 × 106/mL and 100 × 106/mL for 24 h resulted in a dramatic loss of sperm DNA quality, and a high proportion of spermatozoa was fragmented by the time the incubation had ended (Fig. 3a). Nevertheless, SDF values being also high at 24 h compared with T0 was lower in groups with 12 × 106/mL and 6 × 106/mL, respectively (compare value distribution range at Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

a Kaplan–Meier survival curves displaying sperm DNA fragmentation values observed in samples exposed to 200 × 106/mL (blue), 100 × 106/mL (green), 50 × 106/mL (yellow), 25 × 106/mL (pink), 12 × 106/mL (violet), and 6 × 106/mL (orange). b Kaplan–Meier survival curves revealing minimal differences in DNA fragmentation dynamics between samples containing 12 × 106/mL (blue) or 6 × 106/mL (red) spermatozoa

With respect to sperm DNA longevity, the highest r-SDF was observed between T0 and T2. This r-SDF diminished in case of 200 × 106/mL, 100 × 106/mL, 50 × 106/mL, and 25 × 106/mL between T2 and T6, while it slightly increased in the groups containing 12 × 106/mL and 6 × 106/mL. The lowest r-SDF intensity was observed following between T6 and T24. The results on r-SDF following sperm incubation among different experimental groups are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of the rate of sperm DNA fragmentation (r-SDF) values observed in experimental groups

| r-SDF T0–2 | r-SDF T2–6 | r-SDF T6–24 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 200 × 106/mL | 7.28 ± 2.93 (6.18–8.37) | 3.32 ± 1.98 (2.58–4.06) | 1.21 ± 0.59 (0.99–1.46) |

| 100 × 106/mL | 4.86 ± 2.79 (3.82–5.90) | 2.62 ± 1.74 (1.97–3.27) | 1.18 ± 0.61 (0.95–1.41) |

| 50 × 106/mL | 3.47 ± 2.05 (2.07–4.23) | 2.12 ± 1.33 (1.62–2.61) | 0.94 ± 0.56 (0.73–1.15) |

| 25 × 106/mL | 2.25 ± 1.94 (1.53–2.98) | 1.62 ± 1.28 (1.15–2.09) | 0.85 ± 0.48 (0.66–1.03) |

| 12 × 106/mL | 1.83 ± 1.91 (1.11–2.54) | 1.58 ± 1.21 (1.12–2.03) | 0.77 ± 0.49 (0.58–0.95) |

| 6 × 106/mL | 1.64 ± 2.06 (0.87–2.41) | 1.56 ± 1.20 (1.12–2.01) | 0.76 ± 0.45 (0.59–0.93) |

The values are depicted as mean ± SD (CI 95%)

The SDF dynamics followed a pattern corresponding to the data obtained from the static assessment of SDF consistent pattern when r-SDF was higher in samples with higher sperm concentration. The most dramatic loss of sperm DNA quality occurred during the first 2 h of incubation.

Discussion

The experimental rationale used in the present experimental design let us assume that the sperm concentration used for processing is affecting the DNA stability in samples used for insemination purposes. The lower the concentration, the better the DNA longevity, and this is maintained until values of 10 × 106/mL, on average, are achieved. This result has two important implications: (i) for in vitro sperm handling, it is less aggressive to use sperm concentrations close to 10 million per mL. For ICSI, this concentration is enough to select one sperm for injection purposes. (ii) Ten million of spermatozoa seems a physiological condition where spermatozoa do not interact so frequently preventing the negative impact of iatrogenic damage. Interestingly, similar values of sperm concentration to achieve a maximum level of DNA stability were observed in ram, the only species that has been analyzed under such scope by now [12]. Do other mammalian species behave in a similar fashion? By now, this is an open question that when investigated may give some interesting clues about choosing the right logistic pathway for insemination purposes in a wide range of species. What we have observed is that although in vitro DNA longevity is highly dependent of sperm concentration, probably the genetic design associated to each individual is also contributing to show inter-individual differences at equivalent sperm concentrations. In fact, in previous reports a variable ratio between protamine 1 and protamine 2 residues has been detected among different patients [16].

Based on a convincing amount of evidence emphasizing on a strong explanatory value of SDF in distinguishing potentially fertile and infertile subjects [1, 6, 7, 9, 17, 18], several studies have been carried out to establish a threshold value for sperm DNA damage that could provide more insight into the fertilization potential of a semen sample. Among different assays currently available for sperm DNA testing, assessments of the chromatin structure and integrity are described to be simple and precise with high repeatability and predictive value [19]. Different studies [20–22] have established a reference value for SDF ranging between 12 and 25% to differentiate between infertile and fertile subjects.

Even though the semen samples used in this study accomplished the criteria for semen quality, a high degree of individual susceptibility towards DNA fragmentation was observed among the samples where certain subjects presenting a relatively high level of SDF at T0 rapidly increased within 2 h of incubation. At the same time, SDF of such individuals was, to a large extent, unaffected by dilution, indicating that the DNA damage was most likely their inherent feature, most likely indicating a comparatively lower fertility. Inversely, other subjects had a consistently lower level of SDF independently of sperm concentration, which is why it may be speculated that such individuals could have an inherently low level of SDF and consequently might be associated with higher fertility.

The concentration-dependent dynamic behavior of sperm DNA quality provides a new focus on the complex scenario of sperm DNA quality assessment. This aspect relays on the fact that DNA integrity should be considered a marker for semen quality evaluation in ARTs [7, 17, 23], but it could be also considered at the time of organizing the laboratory logistics for ART purposes. Nevertheless, a static consideration of SDF, i.e., a discrete value obtained at a generally unreported time following ejaculation, is currently more accepted. As such, our results reflect on the biological fact that static SDF is only reflecting on a single and specific frame of a complex condition that is dependent upon time, individual, and environment. Such evidence becomes even more important when we consider that at any ART laboratory, fertilization is usually not rapidly performed following semen collection because of logistic delays.

Numerous reports [7, 9, 23–27] focused on the influence of an extended incubation on SDF emphasize on the fact that sperm DNA fragmentation may be considered a complex and dynamic feature, rapidly evolving over the time elapsed between the initial spermiogram and the real use of the semen sample in IUI, IVF, ICSI, or cryopreservation. Because of such dynamic behavior, we must acknowledge that the real reproductive outcome will reflect on the state of sperm DNA molecule at the time of the actual sperm–oocyte interaction rather than during the primary assessment of the ejaculate a few hours prior. In fact, several authors [28, 29] emphasized on a significant time-dependent loss of sperm DNA integrity which may significantly compromise the resulting embryo quality in humans. Similar results were obtained on suitable experimental models such as zebrafish [30] and rabbits [31]. Particularly in the case of zebrafish, although the fertilization rate was not particularly affected after causing an experimental increase of sperm DNA fragmentation by an intentional delay in the use of ejaculates, statistically significant differences were observed in the embryogenesis in comparison with rapidly used semen following ejaculation [29]. In the case of rabbits, the rate of stillborn pups was significantly higher in does inseminated by males with a high r-SDF, when they were compared to those with a low r-SDF. Additionally, the risk of stillborn was higher in males exhibiting high r-SDF values [31]. Accordingly, sperm DNA longevity has the potential to be used in the prognosis of ART outcomes, particularly in the case of IU insemination where DNA longevity could compensate for low sperm concentration or motility.

Processing and incubation conditions of spermatozoa prior to ARTs may also have a significant impact on the sperm DNA longevity. In general, male gametes are incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for at least 1–2 h before ICSI or insemination. Interestingly, Matsuura et al. [25] found that incubation under the conventional conditions, while maintaining temperature and pH, could induce further sperm DNA fragmentation. In our case, we chose to incubate the samples at 37 °C and ambient atmosphere. Although we did not examine SDF either at room temperature or in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, it may be feasible to evaluate sperm DNA longevity under different incubation conditions applicable to a specific ART.

In human ejaculates, the contribution of sperm concentration in the semen quality assessment has been denied. However, in other species this is not the case. A number of reports on mammalian and avian spermatozoa [12, 32–35] have studied the effects of sperm concentration on the quality of semen, particularly following freezing and thawing. There is a general consensus that a greater concentration of spermatozoa results in the reduction of sperm motility and viability. Furthermore, Moghbeli et al. [35] reported that malondialdehyde (MDA), a specific marker of lipid peroxidation, increased correspondingly to the increase of sperm concentration. Such observation could be attributed to the excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by damaged spermatozoa and acrosomal enzymes, which in turn may contribute to the destabilization of vital biomolecules, which could have a larger effect in case of higher sperm concentrations [18, 36, 37]. Oxidative stress has indeed been suggested as one of the leading factors contributing to sperm DNA damage [38–40]. According to this hypothesis, besides possible seminal leukocytes, immature or morphologically defect sperm with excessive amounts of residual cytoplasm may contribute to the resulting seminal oxidative stress [41]. At the same time, oxidative stress may result from an imbalance between ROS overproduction and the activity of antioxidants present in semen [42], which may become more pronounced when the sperm concentration is higher. On the one hand, ROS overgeneration has been implicated as a leading cause for DNA fragmentation in spermatozoa [43], while on the other, semen processing has also been shown to increase ROS generation in sperm [44, 45]. As such, DNA fragmentation in spermatozoa subjected to in vitro handling may be, to a large extent, caused by ROS overproduction and oxidative damage [36, 46, 47]. Dead or dying spermatozoa are likely to substantially contribute to ROS overgeneration [48, 49] via membrane alterations and the release of active enzymes into the medium. Accumulation of toxic metabolites and free enzymes, including those found in the acrosome, may ultimately result in the degeneration of the surviving spermatozoa. As such, when spermatozoa degrade, they may do so cumulatively and exponentially. This theory may explain DNA fragmentation dynamics observed in our experiment, as more concentrated spermatozoa were more likely to be exposed to ROS in comparison to those incubated at lower concentrations, and this effect seems to be more aggressive during the first 2 h of incubation. In this sense, removal of dead or dying spermatozoa prior to any ART using swim-up or Percoll gradient could offer a higher degree of protection for sperm DNA quality. Nevertheless, we must bear in mind that the selection of the appropriate semen processing method is highly dependent on the initial quality of the semen sample, as the specific properties of the ejaculate have a direct consequence on the final choice of a sperm preparation method. While the swim-up procedure or density gradient centrifugation is usually chosen for good-quality samples, a wash procedure is usually selected in case of extreme oligozoospermia for ICSI procedures. In this study, we have used a simple wash procedure to adjust the concentration in normozoospermic samples. As such, it must be noted that a low-quality sample could react differently under the same experimental conditions.

Based on the experimental groups designed in this study, we may predict that highly concentrated semen samples without a well-planned dilution may be likely more vulnerable to increased DNA damage. This negative effect has often been overlooked in clinical andrology and could be associated with poor success of AI or IVF in certain cases of employing significantly more concentrated semen samples. In this respect, more sperm cells may not necessarily be the best option, and an overabundance of spermatozoa could actually be detrimental to the survival of the sperm population as a whole, at least prior to the dilution, such as observed in a number of animal species [12, 33–35].

A question that may be asked is that if sperm concentration has a direct effect on the rate of DNA damage, it would be plausible to know if there is an optimal sperm concentration for each individual, in terms of preventing DNA fragmentation during semen processing. A semen sample containing over 15 million sperm per milliliter is considered normal, according to the WHO [15]; however, there is no recommended sperm concentration for the use of extended or cryopreserved semen in ARTs. In this study, DNA fragmentation in semen samples adjusted to 200 × 106/mL was approximately 3.3 times higher when compared to samples containing 25 × 106 and 3.9 higher in comparison with samples adjusted to 12 × 106/mL following 2 h of in vitro incubation. As such, we may suggest that lowering the sperm concentration of processed semen may be beneficial to the DNA integrity of spermatozoa; however, it is critical to confirm if such a lower sperm concentration could contribute to a higher conception rate. Numerous factors may contribute to real-life fertility rates besides sperm parameters. Results like those here reported let us be iterative on the fact that each ejaculate destined for ART must be considered as a unique specimen and its subsequent manipulation must be performed according to the results of previous tests to fully understand individual in vitro sperm resilience.

An important limitation of this study is the use of PBS to adjust the sperm concentration and for subsequent incubation. Although PBS is a common basic choice for general semen processing, real-time ART procedures involve more complex media, often containing substances providing energy and/or protection to male gametes, such as glucose and antioxidants. Such extenders are suitably buffered to have pH and pKa values most appropriate for use with human gametes as well as for the procedures in which they are commonly used [50]. Furthermore, most extenders for human semen contain proteins (such as serum albumin) and complex components such as egg yolk which may prolong the sperm DNA longevity when compared to buffers free of any supplement [51, 52]. At the same time, a simple semen washing procedure may increase the risk for ROS sources (i.e., already dead or damaged spermatozoa) to be in close contact with healthy gametes [36, 39]. This cumulative effect of ROS derived from all sources may be subsequently negatively correlated with a normal sperm function and fertilization potential in vitro [18, 37, 40]. As such, we may suggest repeating our experiments using low-quality semen samples, complex media for sperm processing, and procedures used more commonly in human ART laboratories.

Conclusion

The individual nature of SDF depending upon time and sperm concentration was revealed in this study, demonstrating that SDF has not a static conception. This is why we are prone to assess sperm DNA fragmentation under standardized conditions of incubation time and sperm concentration, particularly in species with spermatozoa predisposed to experience high rates of DNA damage, and this includes humans. It seems that incubation of spermatozoa for ART purposes should be done following a concentration adjustment below 25 × 106 and with a minor risk if performed at 10 × 106, in order to avoid a higher susceptibility of the sperm DNA molecule towards fragmentation. The information gained from our experiments could be particularly relevant to those reproductive technologies such as AI, IVF, ICSI, all of which require semen survival for extended periods of time before the sperm has reached the oocyte. Logically, as the use of highly diluted semen could reduce the incidence of DNA fragmentation, this may provide better fertility outcomes.

Funding

This study was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness—Programa Retos RTC-2016-4733-1 and by the Slovak Research and Development Agency Grant no APVV-15-0544. The funding bodies had no involvement in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee, with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Auger J, Eustache F, Ducot B, Blandin T, Daudin M, Diaz I, Matribi SE, Gony B, Keskes L, Kolbezen M, Lamarte A, Lornage J, Nomal N, Pitaval G, Simon O, Virant-Klun I, Spira A, Jouannet P. Intra- and inter-individual variability in human sperm concentration, motility and vitality assessment during a workshop involving ten laboratories. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(11):2360–2368. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.11.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lüpold S, Fitzpatrick JL. Sperm number trumps sperm size in mammalian ejaculate evolution. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282(1819):20152122. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karan P, Mohanty TK, Kumaresan A, Bhakat M, Baithalu RK, Verma K, Kumar S, Das Gupta M, Saraf KK, Gahlot SC. Improvement in sperm functional competence through modified low-dose packaging in French mini straws of bull semen. Andrologia. 2018;50:e13003. doi: 10.1111/and.13003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Januskauskas A, Söderquist L, Håård MG, Håård MC, Lundeheim N, Rodriguez-Martinez H. Influence of sperm number per straw on the post-thaw sperm viability and fertility of Swedish red and white A.I. bulls. Acta Vet Scand. 1996;37(4):461–470. doi: 10.1186/BF03548086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inaba Y, Abe R, Geshi M, Matoba S, Nagai T, Somfai T. Sex-sorting of spermatozoa affects developmental competence of in vitro fertilized oocytes in a bull-dependent manner. J Reprod Dev. 2016;62(5):451–456. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2016-032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakkas D, Ramalingam M, Garrido N, Barratt CL. Sperm selection in natural conception: what can we learn from Mother Nature to improve assisted reproduction outcomes? Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(6):711–726. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tvrdá E, López-Fernández C, Sánchez-Martín P, Gosálvez J. Sperm DNA fragmentation in donors and normozoospermic patients attending for a first spermiogram: static and dynamic assessment. Andrologia. 2018. 10.1111/and.12986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Zheng JF, Chen XB, Zhao LW, Gao MZ, Peng J, Qu XQ, Shi HJ. Jin XL. ICSI treatment of severe male infertility can achieve prospective embryo quality compared with IVF of fertile donor sperm on sibling oocytes. Asian J Androl. 2015;17(5):845–849. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.146971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gosálvez J, Cortés-Gutiérrez EI, Nuñez R, Fernández JL, Caballero P, López-Fernández C, Holt WV. A dynamic assessment of sperm DNA fragmentation versus sperm viability in proven fertile human donors. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(6):1915–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gosálvez J, López-Fernández C, Fernández JL, Gouraud A, Holt WV. Relationships between the dynamics of iatrogenic DNA damage and genomic design in mammalian spermatozoa from eleven species. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78(12):951–961. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosálvez J, García-Ochoa C, Ruíz-Jorro M, Martínez-Moya M, Sánchez-Martín P, Caballero P. ¿A qué velocidad “muere” el ácido desoxirribonucleico del espermatozoide tras descongelar muestras seminales procedentes de donantes? Rev Int Androl. 2013;11:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.López-Fernández C, Johnston SD, Fernández JL, Wilson RJ, Gosálvez J. Fragmentation dynamics of frozen-thawed ram sperm DNA is modulated by sperm concentration. Theriogenology. 2010;74(8):1362–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setchell BP. Sperm counts in semen of farm animals 1932-1995. Int J Androl. 1997;20(4):209–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1997.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.David I, Kohnke P, Lagriffoul G, Praud O, Plouarboué F, Degond P, Druart X. Mass sperm motility is associated with fertility in sheep. Anim Reprod Sci. 2015;161:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esteves SC, Zini A, Aziz N, Alvarez JG, Sabanegh ES, Jr, Agarwal A. Critical appraisal of World Health Organization's new reference values for human semen characteristics and effect on diagnosis and treatment of subfertile men. Urology. 2012;79(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García-Peiró A, Martínez-Heredia J, Oliver-Bonet M, Abad C, Amengua JM, Navarro J, Jones C, Coward K, Gosálvez J, Benet J. Protamine P1/P2 ratio correlates with dynamic aspects of DNA fragmentation in human sperm. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gosálvez J, Caballero P, López-Fernández C, Ortega L, Guijarro JA, Fernández JL, Johnston SD, Nuñez-Calonge R. Can DNA fragmentation of neat or swim-up spermatozoa be used to predict pregnancy following ICSI of fertile oocyte donors? Asian J Androl. 2013;15(6):812–818. doi: 10.1038/aja.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorostghoal M, Kazeminejad SR, Shahbazian N, Pourmehdi M, Jabbari A. Oxidative stress status and sperm DNA fragmentation in fertile and infertile men. Andrologia. 2017;49(10):e12762. doi: 10.1111/and.12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evenson DP. Sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA®): 30 years of experience with the SCSA®. In: Zini A, Agarawal A, editors. Sperm chromatin. Biological and clinical applications in male infertility and assisted reproduction. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 125–149. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sergerie M, Laforest G, Bujan L, Bissonnette F, Bleau G. Sperm DNA fragmentation: threshold value in male fertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:3446–3451. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benchaib M, Braun V, Lornage J, Hadj S, Salle B, Lejeune H, Guérin JF. Sperm DNA fragmentation decreases the pregnancy rate in an assisted reproductive technique. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1023–1028. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henkel R, Kierspel E, Hajimohammad M, Stalf T, Hoogendijk C, Mehnert C, Menkveld R, Schill WB, Kruger TF. DNA fragmentation of spermatozoa and assisted reproduction technology. Reprod BioMed Online. 2003;7:477–484. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61893-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Zhu L, Jiang H, Chen H, Chen Y, Dai Y. Sperm DNA fragmentation index and pregnancy outcome after IVF or ICSI: a meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32(1):17–26. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0374-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosálvez J, Cortés-Gutierez E, López-Fernández C, Fernández JL, Caballero P, Nuñez R. Sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation dynamics in fertile donors. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(1):170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuura R, Takeuchi T, Yoshida A. Preparation and incubation conditions affect the DNA integrity of ejaculated human spermatozoa. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:753–759. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed I, Abdelateef S, Laqqan M, Amor H, Abdel-Lah MA, Hammadeh ME. Influence of extended incubation time on human sperm chromatin condensation, sperm DNA strand breaks and their effect on fertilisation rate. Andrologia. 2018. 10.1111/and.12960. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Nabi A, Khalili MA, Halvaei I, Roodbari F. Prolonged incubation of processed human spermatozoa will increase DNA fragmentation. Andrologia. 2014;46:374–379. doi: 10.1111/and.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young KE, Robbins WA, Xun L, Elashoff D, Rothmann SA, Perreault SD. Evaluation of chromosome breakage and DNA integrity in sperm: an investigation of remote semen collection conditions. J Androl. 2003;24(6):853–861. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gosálvez J, Johnston S, López-Fernández C, Gosálbez A, Arroyo F, Fernández JL, Álvarez JG. Sperm fractions obtained following density gradient centrifugation in human ejaculates show differences in sperm DNA longevity. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2014;3(2):116–120. doi: 10.1016/S2305-0500(14)60014-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gosálvez J, López-Fernández C, Hermoso A, Fernández JL, Kjelland ME. Sperm DNA fragmentation in zebrafish (Danio rerio) and its impact on fertility and embryo viability—implications for fisheries and aquaculture. Aquaculture. 2014;433:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.05.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnston SD, López-Fernández C, Arroyo F, Gosálbez A, Cortés Gutiérrez EI, Fernández JL, Gosálvez J. Reduced sperm DNA longevity is associated with an increased incidence of still born; evidence from a multi-ovulating sequential artificial insemination animal model. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(9):1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0754-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banasewska D, Kondracki S, Wysokińska A. Effect of sperm concentration on ejaculate for morphometric traits of spermatozoas of the pietrain breed boars. J Cent Eur Agric. 2009;10(4):383–396. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salazar JL, Jr, Teague SR, Love CC, Brinsko SP, Blanchard TL, Varner DD. Effect of cryopreservation protocol on postthaw characteristics of stallion sperm. Theriogenology. 2011;76(3):409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Contri A, Gloria A, Robbe D, Sfirro MP, Carluccio A. Effect of sperm concentration on characteristics of frozen-thawed semen in donkeys. Anim Reprod Sci. 2012;136(1–2):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moghbeli M, Kohram H, Zare-Shahaneh A, Zhandi M, Sharideh H, Sharafi M. Effect of sperm concentration on characteristics and fertilization capacity of rooster sperm frozen in the presence of the antioxidants catalase and vitamin E. Theriogenology. 2016;86(6):1393–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iommiello VM, Albani E, Di Rosa A, Marras A, Menduni F, Morreale G, Levi SL, Pisano B, Levi-Setti PE. Ejaculate oxidative stress is related with sperm DNA fragmentation and round cells. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:321901. doi: 10.1155/2015/321901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oluwakemi O, Olufeyisipe A. DNA fragmentation and oxidative stress compromise sperm motility and survival in late pregnancy exposure to omega-9 fatty acid in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2016;19(5):511–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gosálvez J, López-Fernández C, Fernández JL, Esteves SC, Johnston SD. Unpacking the mysteries of sperm DNA fragmentation. Ten frequently asked questions. J Reprod Biotechnol Fertil. 2015;4:1–16. doi: 10.1177/2058915815594454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aitken RJ, Gibb Z, Baker MA, Drevet J, Gharagozloo P. Causes and consequences of oxidative stress in spermatozoa. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2016;28(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1071/RD15325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aitken RJ. DNA damage in human spermatozoa; important contributor to mutagenesis in the offspring. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(Suppl 4):S761–S764. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.09.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agarwal A, Qiu E, Sharma R. Laboratory assessment of oxidative stress in semen. Arab J Urol. 2018;16(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palani AF. Effect of serum antioxidant levels on sperm function in infertile male. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2018;23(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2017.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aitken RJ, De Luliis GN, McLachlan RI. Biological and clinical significance of DNA damage in the male germ line. Int J Androl. 2008;32:46–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2008.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomson LK, Fleming SD, Aitken RJ, De luliis GN, Zieschang JA, Clark AM. Cryopreservation-induced human sperm DNA damage is predominantly mediated by oxidative stress rather than apoptosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2061–2070. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghaleno LR, Valojerdi MR, Hassani F, Chehrazi M, Janzamin E. High level of intracellular sperm oxidative stress negatively influences embryo pronuclear formation after intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment. Andrologia. 2014;46(10):1118–1127. doi: 10.1111/and.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ball BA. Oxidative stress, osmotic stress and apoptosis: impacts on sperm function and preservation in the horse. Anim Reprod Sci. 2008;107:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucio CF, Regazzi FM, Silva LCG, Angrimani DSR, Nichi M, Vannucchi CI. Oxidative stress at different stages of two-step semen cryopreservation procedures in dogs. Theriogenology. 2016;85(9):1568–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahfouz RZ, Du Plessis SS, Aziz N, Sharma R, Sabanegh M, Agarwal A. Sperm viability, apoptosis, and intracellular reactive oxygen species levels in human spermatozoa before and after induction of oxidative stress. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aitken RJ, Baker MA, Nixon B. Are sperm capacitation and apoptosis the opposite ends of a continuum driven by oxidative stress? Asian J Androl. 2015;17(4):633–639. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.153850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Will MA, Clark NA, Swain JE. Biological pH buffers in IVF: help or hindrance to success. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28(8):711–724. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9582-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peirce KL, Roberts P, Ali J, Matson P. The preparation and culture of washed human sperm: a comparison of a suite of protein-free media with media containing human serum albumin. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2015;4(3):222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.apjr.2015.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ying-Fu Shih YF, Tzeng SL, Chen WJ, Huang CC, Chen HH, Lee TH, et al. Effects of synthetic serum supplementation in sperm preparation media on sperm capacitation and function test results. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016. 10.1155/2016/1027158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]