Abstract

Background

Nattokinase (NK), which is a member of the subtilisin family, is a potent fibrinolytic enzyme that might be useful for thrombosis therapy. Extensive work has been done to improve its production for the food industry. The aim of our study was to enhance NK production by tandem promoters in Bacillus subtilis WB800.

Results

Six recombinant strains harboring different plasmids with a single promoter (PP43, PHpaII, PBcaprE, PgsiB, PyxiE or PluxS) were constructed, and the analysis of the fibrinolytic activity showed that PP43 and PHpaII exhibited a higher expression activity than that of the others. The NK yield that was mediated by PP43 and PHpaII reached 140.5 ± 3.9 FU/ml and 110.8 ± 3.6 FU/ml, respectively. These promoters were arranged in tandem to enhance the expression level of NK, and our results indicated that the arrangement of promoters in tandem has intrinsic effects on the NK expression level. As the number of repetitive PP43 or PHpaII increased, the expression level of NK was enhanced up to the triple-promoter, but did not increase unconditionally. In addition, the repetitive core region of PP43 or PHpaII could effectively enhance NK production. Eight triple-promoters with PP43 and PHpaII in different orders were constructed, and the highest yield of NK finally reached 264.2 ± 7.0 FU/ml, which was mediated by the promoter PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43. The scale-up production of NK that was promoted by PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43 was also carried out in a 5-L fermenter, and the NK activity reached 816.7 ± 30.0 FU/mL.

Conclusions

Our studies demonstrated that NK was efficiently overproduced by tandem promoters in Bacillus subtilis. The highest fibrinolytic activity was promoted by PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43, which was much higher than that had been reported in previous studies. These multiple tandem promoters were used successfully to control NK expression and might be useful for improving the expression level of the other genes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12866-019-1461-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Nattokinase, Tandem promoter, Core promoter region, Bacillus subtilis, Recombinant enzyme

Background

Nattokinase (NK, E.C. 3.4.21.62) was first identified by Sumi et al. from “Natto”, which is a popular traditional Japanese soybean food [1]. NK, as a potent fibrinolytic enzyme, can directly cleave cross-linked fibrin in vitro and inactivate the fibrinolysis inhibitor or catalyze the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin [2, 3]. Studies in rats showed that NK exhibited 5-fold more fibrinolytic activity than that of plasmin [4]. Compared with other thrombolytic reagents, including urokinase, tissue type plasminogen activator (t-PA) and streptokinase, NK has advantages in preventative and prolonged effects, with few side effects and stability in the gastrointestinal tract [5]. The NK gene was cloned and characterized, and protein engineering techniques and site-directed mutagenesis were carried out to improve NK stability [6–10]. The NK enzyme is usually industrially produced by the wild-type Bacillus subtilis natto (B. subtilis natto) [11].

The species B. subtilis is a good host strain for the industrial production of the NK enzyme, as NK was isolated from B. subtilis natto. B. subtilis is a gram-positive bacterium and is a well-studied host for the expression of heterologous proteins because of its many attractive features [12]. As a model organism, B. subtilis is widely used in laboratory studies because it is easy to culture and has a high-level secretory system. In addition, B. subtilis is a food-grade safety strain and presents no safety concerns, as reviewed by the U.S. FDA Center. Some efficient expression systems have been constructed to promote the production of homologous and heterologous proteins in B. subtilis, because of its well-characterized physiological and biochemical properties and nonpathogenicity [13–15]. B. subtilis strains has been engineered as extracellular-protease deficient strains for the overexpression of subtilisin and β-lactamase in B. subtilis WB600 [16, 17], the overexpression of staphylokinase and xylanase in B. subtilis WB700 [18, 19], and the overexpression of phospholipase C in B. subtilis WB800 [20]. In addition, several studies have reported the secretory overexpression of NK in recombinant B. subtilis strains [21, 22].

As is well known, the promoter-regulated gene transcription is usually located upstream of the gene. There are two kinds of promoters: the constitutive promoter that is active in all circumstances and the regulated promoter that become active only in response to specific stimulation in the cell. Because the promoter is a crucial aspect of the expression system, many strong promoters have been screened and characterized in B. subtilis [23–26]. Recent studies have increasingly focused on the strategy to improve the expression level of recombinant proteins or peptides by the construction of tandem promoters and promoter engineering. Using engineered promoters by altering the − 10 or − 35 region led to a much higher production of recombinant proteins [27, 28]. Widner et al. had studied the gene expression in B. subtilis and found that the expression level of the gene could increase by using expression systems that contain two or three tandem promoters in contrast to a single promoter. The study demonstrated that the expression of aprL achieved a high level by combining the mutant amyQ promoter with the promoter of the cry3A gene [29]. The thermostable 4-α-glucanotransferase from Thermus scotoductus was overexpressed in B. subtilis, and its productivity was elevated by more than ten-fold when promoted by a dual-promoter system, compared to that of the single HpaII promoter system [30]. Researchers have investigated the strength of single and dual promoters for overexpression of aminopeptidase in B. subtilis. In addition, the dual-promoter PgsiB–PHpaII gave the best performance, which was much higher than PHpaII and PgsiB [31]. The system containing a dual-promoter PHpaII-PamyQ′ was found to sustain superior expression of β-cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase in a B. subtilis strain (CCTCC M 2016536) [32]. Okegawa and Motohashi successfully expressed the functional ferredoxin-thioredoxin reductase by using a system containing tandem T7 promoters in Escherichia coli [33].

In this study, we aimed to increase the secretory expression of NK in B. subtilis WB800 by mediating the gene expression promotion by tandem promoters. Six constitutive promoters, PHpaII, PP43, PBcaprE, PluxS, PgsiB and PyxiE, were selected, and a series of expression cassettes containing single promoters, dual-promoters and triple-promoters was achieved by arranging promoters in different orders. The efficacies of these multiple tandem promoters for controlling the expression of NK are presented.

Results

Construction of expression cassettes for overexpression of nattokinase

Six strong and widely used promoters, PHpaII, PP43, PBcaprE, PluxS, PgsiB and PyxiE, were selected as targets for enhancing the production of NK, and their origins and characteristics are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The plasmid pSG-PHpaII was constructed in our previous study [31]. Then, the plasmid pSG-pro-NK with no promoter was constructed first, and five promoters were employed to construct the plasmids pSG-PP43, pSG-PBcaprE, pSG-PluxS, pSG-PgsiB and pSG-PyxiE following the MEGAWHOP method (Fig. 1a).

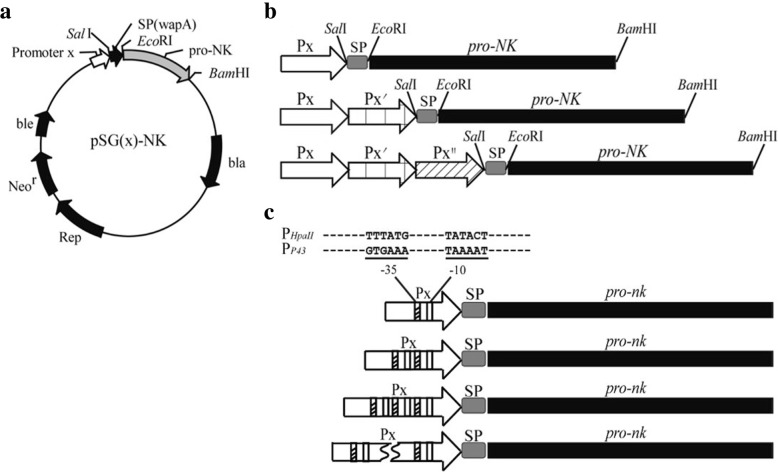

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the expression cassettes. a Map of the pSG(x)-NK vectors. All of the expression cassettes were cloned into the pMA0911-wapA-pro-NK, and the sites of the relevant restriction enzymes were shown. b The schematic diagram of the expression cassettes with tandem promoters. The signal peptide (SP) and the NK gene are represented by gray and black, respectively. The promoters, PX, are represented by arrows. c The expression cassettes with repetitive core regions of promoters. The sequences of core regions (− 35 and − 10) are shown

As shown in Fig. 1b, plasmids harboring multiple promoters in tandem were constructed (pSG-PX-PY-PZ). These six promoters were further inserted into the downstream region of different promoters to result in fourteen kinds of plasmids in which the NK was controlled by dual-promoters. Based on the NK expression level of recombinant strains under the control of dual-promoters, promoter P43 and HpaII were combined in the pattern of three and four promoters in tandem, and ten different kinds of promoters were successfully obtained.

In addition, another type of tandem promoter (pSG-nCPX) was constructed, as shown in Fig. 1c. The core region of the promoter (− 10 and − 35 region) was amplified and linked in tandem repeats. All of the plasmids for the NK expression that was constructed in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains or plasmids | Description | Source | Highest yield of NK (U/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| Escherichia coli JM109 | RecA1 pupE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi∆(lac-proAB) F′[traD36 proAB+lacIq lacZ∆M15] | Lab stock | – |

| Bacillus subtilis WB800 | nprE aprE epr bpr mpr::ble nprB::bsr ∆vpr wprA::hyg | Lab stock | – |

| Plasmids | |||

| pMA0911-pro-NK | shuttle vector for E. coli/B. subtilis, PHpaII, SPwapA, pro-NK, Apr, Kmr, | Lab stock | 110.8 ± 5.2 |

| pSG-pro-NK | pMA0911-pro-NK without promoter PHpaII | This study | – |

| pSG-PBcaprE | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PBcaprE | This study | 103.5 ± 4.2 |

| pSG-PluxS | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PluxS | This study | 99.2 ± 3.8 |

| pSG-PgsiB | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PgsiB | This study | 44.6 ± 2.9 |

| pSG-PyxiE | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PyxiE | This study | 20.2 ± 2.0 |

| pSG-PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43 | This study | 140.5 ± 2.5 |

| pSG-2PgsiB | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PgsiB-PgsiB | This study | 48.0 ± 2.2 |

| pSG-2PBcaprE | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PBcaprE-PBcaprE | This study | 120.3 ± 2.4 |

| pSG-2PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PHpaII | This study | 199.4 ± 7.1 |

| pSG-2PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43-PP43 | This study | 157.2 ± 4.0 |

| pSG-PP43-PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43-PHpaII | This study | 231.7 ± 6.0 |

| pSG-PHpaII-PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PP43 | This study | 210.6 ± 5.2 |

| pSG-PBcaprE-PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PBcaprE-PHpaII | This study | 175.5 ± 5.0 |

| pSG-PHpaII-PBcaprE | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PBcaprE | This study | 0 |

| pSG-PyxiE-PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PyxiE-PHpaII | This study | 0 |

| pSG-PHpaII-PyxiE | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PyxiE | This study | 166.7 ± 2.5 |

| pSG-PgsiB-PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PgsiB-PHpaII | This study | 164.9 ± 3.0 |

| pSG-PHpaII-PgsiB | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PgsiB | This study | 0 |

| pSG-PluxS-PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PluxS-PHpaII | This study | 77.5 ± 4.0 |

| pSG-PHpaII-PluxS | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PluxS | This study | 0 |

| pSG-3PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII | This study | 213.3 ± 4.1 |

| pSG-3PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43-PP43-PP43 | This study | 219.2 ± 7.7 |

| pSG-2PHpaII-PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43 | This study | 264.2 ± 7.0 |

| pSG-PP43-2PHpaIII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43-PHpaII-PHpaII | This study | 47.5 ± 3.1 |

| pSG-PHpaII-2PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PP43-PP43 | This study | 199.4 ± 7.1 |

| pSG-2PP43-PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43-PP43-PHpaII | This study | 149.4 ± 5.0 |

| pSG-PHpaII-PP43-PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PP43-PHpaII | This study | 206.3 ± 7.0 |

| pSG-PP43-PHpaII-PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43-PHpaII-PP43 | This study | 182.3 ± 5.6 |

| pSG-4PHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII | This study | 200.0 ± 2.6 |

| pSG-4PP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter PP43-PP43-PP43-PP43 | This study | 222.9 ± 4.8 |

| pSG- 2CPBcaprE | pSG-pro-NK with promoter CPBcaprE-PBcaprE | This study | 120.3 ± 2.4 |

| pSG-2CPHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter CPHpaII-PHpaII | This study | 200.8 ± 4.6 |

| pSG-3CPHpaII | pSG-pro-NK with promoter CPHpaII-CPHpaII-PHpaII | This study | 138.3 ± 3.8 |

| pSG-2CPP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter CPP43-PP43 | This study | 166.7 ± 5.3 |

| pSG-3CPP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter CPP43-CPP43-PP43 | This study | 181.7 ± 6.3 |

| pSG-4CPP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter CPP43-CPP43-CPP43-PP43 | This study | 231.7 ± 8.0 |

| pSG-5CPP43 | pSG-pro-NK with promoter CPP43-CPP43-CPP43-CPP43-PP43 | This study | 254.2 ± 5.1 |

Note: The corresponding highest yield of NK for each construct was detected using the 36-h supernatant

Expression of nattokinase in B. subtilis WB800 with a single promoter

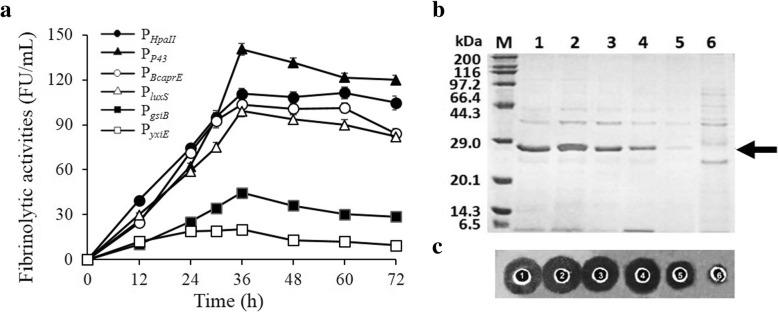

To compare the abilities of those six promoters to promote NK expression, the six strains harboring the different plasmids, pSG-PHpaII, pSG-PP43, pSG-PBcaprE, pSG-PluxS, pSG-PgsiB and pSG-PyxiE, were cultivated in TB medium. The effects of these single promoters on the secretory expression level of recombinant NK were determined by SDS-PAGE and fibrinolytic analysis (Fig. 2). Fibrinolytic activity curves showed that the highest activity was achieved at 36 h (Fig. 2a). The highest yield of NK mediated by PHpaII was 110.8 ± 3.6 FU/ml, while the maximum NK activity was 140.5 ± 3.9 FU/ml produced by the strain harboring pSG-PP43. The expression levels under the control of PBcaprE (103.5 ± 4.2 FU/ml) and PluxS (99.2 ± 3.8 FU/ml) were similar, second only to the expression under the control of PHpaII. The promoter PyxiE (20.2 ± 2.0 FU/ml) exhibited the lowest expression level of NK among the six promoters, and its promoter strength was only 14% of PP43. The results of SDS-PAGE and the fibrin plate assay supported the above fibrinolytic analysis results (Fig. 2b and c).

Fig. 2.

Effects of different single promoters on the overexpression of NK. (a) Fibrinolytic activities of NK in the supernatant. The recombinant strains having different single promotes were cultured in TB medium for 72 h with periodical sampling. b SDS-PAGE analysis. Recombinant strains having different single promoters were cultured in the TB medium for 36 h, and then the cells and the supernatant culture were separated by centrifugation. Supernatant (15 μL) was loaded into each lane. Lane M: standard marker proteins; Lane 1–6: PHpaII; PP43; PBcaprE; PluxS; PgsiB and PyxiE. The arrow indicates that the NK bands correspond to 36-h supernatant. c Fibrin plate analysis. Transparent zones produced by the enzyme activity of NK and its variants in the supernatant, which was induced for 36 h, were examined by the fibrin plate method, which was conducted at 37 °C for 4 h. 1–6: PHpaII; PP43; PBcaprE; PluxS; PgsiB and PyxiE

Effects of different dual-promoter systems on nattokinase expression

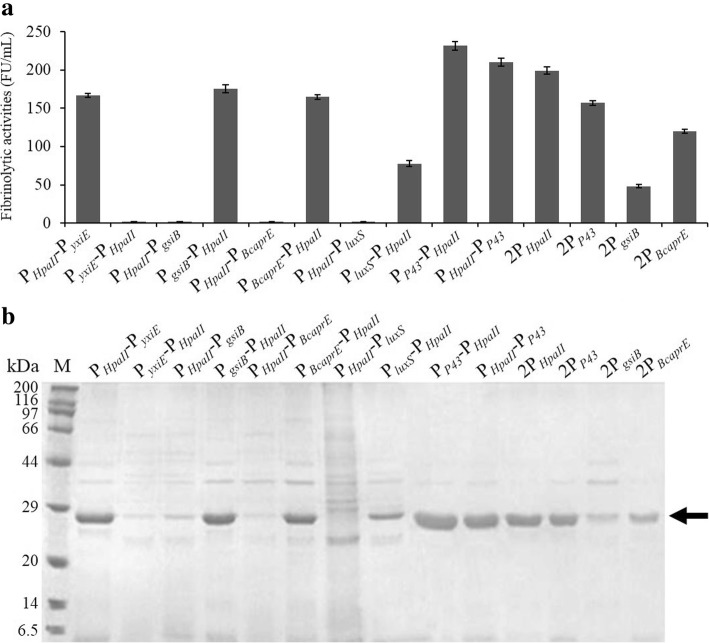

To investigate whether two of these promoters in tandem could enhance NK production, fourteen types of dual-promoters were constructed. The effects of these dual-promoter systems on the expression of recombinant NK were compared by SDS-PAGE and by measuring the fibrinolytic activity (Fig. 3). The NK expression from these dual-promoters containing two of the same promoters was constitutively increased compared with that from a single promoter, such as PP43-PP43 (157.2 ± 3.0 FU/ml) compared with PP43 (140.5 ± 3.9 FU/ml), PHpaII-PHpaII (199.4 ± 4.8 FU/ml) compared with PHpaII (110.8 ± 3.6 FU/ml), PBcaprE-PBcaprE (120.3 ± 2.4 FU/ml) compared with PBcaprE (103.5 ± 4.2 FU/ml), and PgsiB-PgsiB (48.0 ± 2.2 FU/ml) compared with PgsiB (44.6 ± 2.9 FU/ml). These results showed that the experiments involving PgsiB in tandem or separately did not exhibit an efficient expression of NK.

Fig. 3.

Overproduction of NK under the control of the dual-promoter systems. a Fibrinolytic activities of NK in the supernatant. b SDS-PAGE analysis. Lane M: standard marker proteins. The position of the NK protein bands is indicated by an arrow. Recombinant strains having different dual-promotes were cultured in the TB medium for 36 h, and then the cells and the supernatant culture were separated by centrifugation

Intriguingly, the dual-promoter system containing different promoters showed that the order of two promoters has an important effect on the expression of NK. The NK activity under the control of PHpaII-PyxiE was approximately 166.7 ± 2.5 FU/ml, but the production under the control of PyxiE-PHpaII displayed an obviously opposite effect, in which the expression of NK was undetected (0 FU/ml). Similar results were observed in strains harboring pSG-PgsiB-PHpaII (164.9 ± 3.0 FU/ml) and pSG-PHpaII-PgsiB (0 FU/ml), pSG-PBcaprE-PHpaII (175.5 ± 5.0 FU/ml) and pSG-PHpaII-PBcaprE (0 FU/ml), and pSG-PluxS-PHpaII (77.5 ± 4.0 FU/ml) and pSG-PHpaII-PluxS (0 FU/ml).

However, regardless of how PHpaII and PP43 were arranged in tandem, NK was expressed at a high level in the recombinant strain B. subtilis WB800. The NK yield mediated by pSG-PP43-PHpaII reached the highest value (231.7 ± 6.0 FU/ml), which increased by 109% when compared with PHpaII and 64.9% when compared with PP43. The strain harboring pSG-PHpaII-PP43 exhibited the second highest expression of 210.6 ± 5.2 FU/ml. The result of the SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 3b) was supported by the above results of the fibrinolytic activity. These results showed that NK expression levels under the control of these double promoters were clearly different from each other.

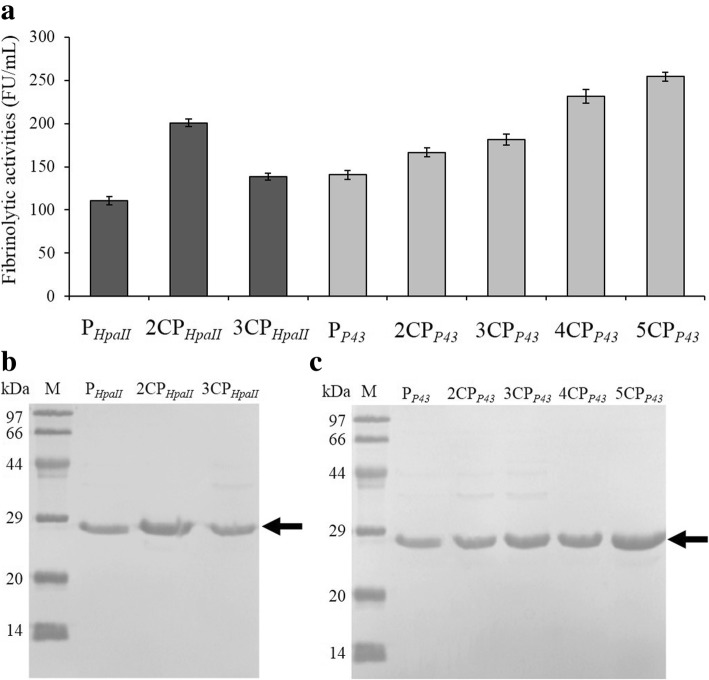

Effects of different triple-promoters on the nattokinase expression

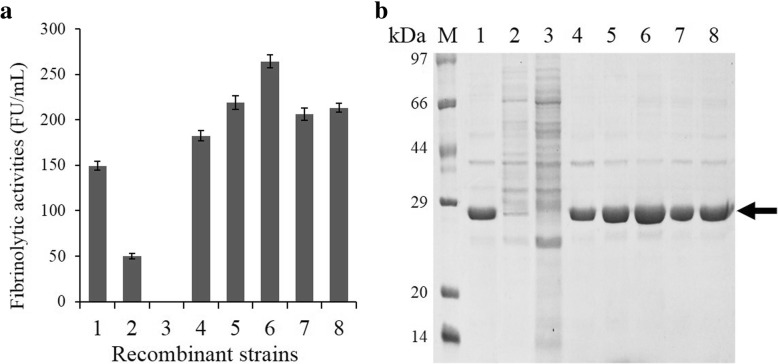

Analysis of NK production showed that promoters PHpaII and PP43 could efficiently promote the expression of NK. To further improve NK production, the expression profiles of eight recombinant strains with three tandem promoters were determined by enzymatic activities and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4a, the NK expression mediated by pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43 reached the highest activity, 264.2 ± 7.0 FU/ml, which was 14% higher than that under the control of the dual-promoter PP43-PHpaII. The triple-promoters PHpaII-PP43-PHpaII (206.3 ± 7.0 FU/ml) and PP43-PHpaII-PP43 (182.3 ± 5.6 FU/ml) showed similar promoter strengths, and the production that was promoted by both improved considerably compared with the production of PHpaII and PP43. In contrast, PP43-PHpaII-PHpaII (47.5 ± 3.1 FU/ml) did not exhibit an efficient expression of NK, and PHpaII-PP43-PP43 (0 FU/ml) exhibited no expression of NK. These results indicated that the arrangement of the promoters in tandem has intrinsic effects on the expression level of the target protein.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the NK production mediated by different triple-promoter systems. a Fibrinolytic activities of NK in the supernatant. b SDS-PAGE analysis of the culture supernatant. Recombinant strains promoted by different triple-promoters were cultured in the TB medium for 36 h, and then cells and the supernatant culture were separated by centrifugation. Lane 1–8: PP43-PP43-PHpaII, PP43-PHpaII-PHpaII, PHpaII-PP43-PP43, PP43-PHpaII-PP43, PP43-PP43-PP43, PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43, PHpaII-PP43-PHpaII, and PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII; Lane M: standard marker proteins. The arrow indicates NK bands

The NK production of the strain harboring pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII (213.3 ± 5.1 FU/ml) was increased by 92.2% compared with that under the control of pSG-PHpaII, and by 7% compared with that under the control of pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII. Furthermore, pSG-PP43-PP43-PP43 (219.2 ± 7.7 FU/ml) enhanced the NK production by 55.9% compared with pSG-PP43, and 39.4% compared with pSG-PP43-PP43. The above results of the fibrinolytic activity assays were consistent with those of SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 4b).

As the number of promoters increased, the level of NK expression was enhanced up to the triple-promoter. Therefore, we constructed quad-promoter systems, PP43-PP43-PP43-PP43 and PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII, to test whether the enhancement of NK expression would continue by increasing repetitive promoters. The results in Table 2 showed that the NK activity in the supernatant induced by PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII-PHpaII decreased slightly. Moreover, the NK production mediated by PP43-PP43-PP43-PP43 was almost as same as that mediated by PP43-PP43-PP43. These results documented that the expression level of the target protein will not increase unconditionally with the increase in the number of promoters PP43 or PHpaII.

Table 2.

Nattokinase yield under the control of tandem repeats containing whole sequence or core region of PHpaII and PP43

| Single | Whole promoter region in tandem |

Core promoter region in tandem |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter | Activity (FU/mL) | Promoter | Activity (FU/mL) | Promoter | Activity (FU/mL) |

| PHpaII | 110.8 ± 5.2 | 2PHpaII | 199.4 ± 7.1 | 2CPHpaII | 200.8 ± 4.6 |

| 3PHpaII | 213.3 ± 4.1 | 3CPHpaII | 138.3 ± 3.8 | ||

| 4PHpaII | 200.0 ± 2.6 | ||||

| PP43 | 140.5 ± 2.5 | 2PP43 | 157.2 ± 4.0 | 2CPP43 | 166.7 ± 5.3 |

| 3PP43 | 219.2 ± 7.7 | 3CPP43 | 181.7 ± 6.3 | ||

| 4PP43 | 222.9 ± 4.8 | 4CPP43 | 231.7 ± 8.0 | ||

| 5CPP43 | 254.2 ± 5.1 | ||||

Nattokinase expression mediated by core region of PHpaII and PP43 in tandem repeats

These two promoters, PP43 and PHpaII, had strong abilities to overexpress the recombinant NK in B. subtilis WB800. Considering that the length of the promoter affects its expression activity, plasmids harboring the core region of PP43 or PHpaII in tandem repeats (pSG-nCPX) were constructed, as shown in Fig. 1c. The NK expression activity of plasmids pSG-nCPX was determined by the fibrinolytic activity and SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of the multi core regions of PHpaII and PP43 in tandem on NK production. a The fibrinolytic activities of NK in the supernatant. Recombinant strains harboring promoters of repetitive core regions were cultured in TB medium for 36 h, and then cells and the supernatant culture were separated by centrifugation. The SDS-PAGE analysis of the NK expression mediated by the repetitive core regions of PHpaII (b) and PP43 (c). The arrow indicates the NK bands corresponding to the 36-h supernatant, and 15 μL supernatant was loaded into each lane

As shown in Fig. 5a, the NK production of the strain harboring pSG-2CPHpaII (200.8.2 ± 4.6 FU/ml) was increased by 81.2% compared with pSG-PHpaII. However, the NK production promoted by 3CPHpaII (138.3 ± 3.8 FU/ml) decreased by 31.1% compared with that promoted by 2CPHpaII. It could be seen that the NK expression that was mediated by pSG-5CPP43 (254.2 ± 5.1 FU/ml) was 80.9% higher than that mediated by pSG-PP43. The expression level of NK increased with the increase in the number of core regions of PP43 up to five. The SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the NK expressive quantity in the supernatant produced by pSG-nCPHpaII (Fig. 5b) and pSG-nCPP43 (Fig. 5c) was consistent with the results of the NK activity assay. These results suggested that the core regions of PP43 and PHpaII could produce and enhance the expression level of NK efficiently.

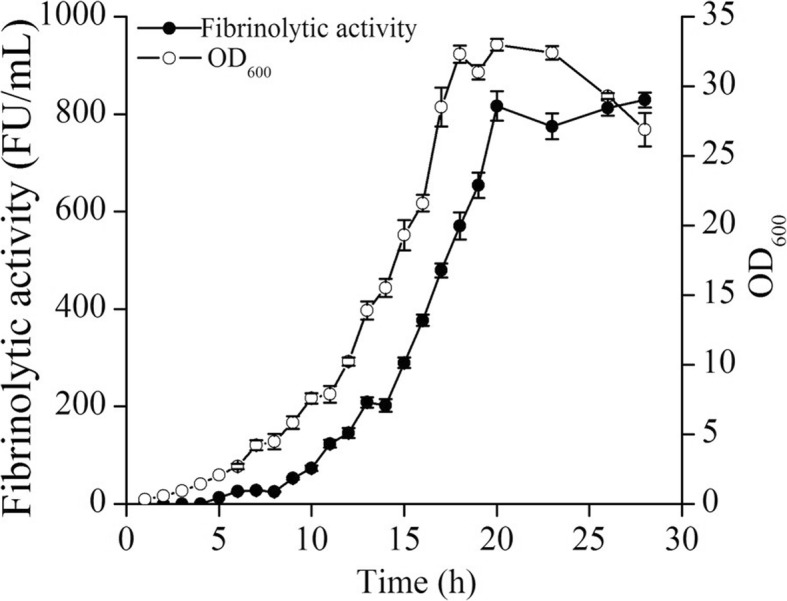

Scale-up expression of nattokinase in a 5-L fermenter using the strain harboring pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43

Our results indicated that the highest overexpression level of NK was produced by the triple-promoter PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43. Based on the results of the optimization of the cultivation conditions in shaking flask experiments (data not shown), the scale-up of recombinant NK production was completed in a 5-L fermenter using the strain harboring pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43. The process for the cultivation in the fermenter is shown in Fig. 6. The cell density reached the highest OD600 value of 33.0 ± 0.4 at 20 h. Similar to the cell growth, NK production was significantly increased and reached the highest value of 816.7 ± 30.0 FU/ml at 20 h, which was the highest value ever reported. NK production was about two-fold higher in the 5-L fermenter compared to that of the shaking flask experiments. These results indicated that the strain harboring pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43 had great potential for the industrial production of NK.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of fermentation of NK in the recombinant strain harboring pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43. The fermentation was carried out in a 5-L fermenter, and the cell growth and NK activity were measured by taking a sample every 2 h

Discussion

Six promoters having high expression strength were selected to overexpress the NK enzyme in B. subtilis WB800, and the overexpression of NK mediated by those single promoter systems exhibited significantly different levels. In our study, the highest expression level of NK driven by a single promoter was 140.5 ± 3.9 FU/ml as induced by PP43. The order of the strength of the six single promoters mediating NK expression in B. subtilis was PP43 > PHpaII > PBcaprE > PluxS > PgsiB > PyxiE. However, Guan et al. reported that the activity of the single promoter PP43 was lower than that of PluxS and PyxiE for aminopeptidase expression in B. subtilis [31]. In addition, Zhang et al. reported that PyxiE exhibited higher expression strengths than PP43, both in B. subtilis and E. coli [23]. The expression level of the target gene is naturally determined by the promoter, signal peptide and host, and many studies have suggested that the effect of the promoter strength on the heterologous expression varies. Our results are consistent with the effect of a promoter varying with the change in the target gene [34]. The growth curves of strains containing a single promoter were approximately same (Additional file 1: Figure S1), and this result confirmed that the expression cassettes with different promoters, not the cell amount, caused the different expression levels of NK.

The NK expression level driven by a dual-promoter PP43-PP43 reached 157.2 ± 3.0 FU/ml, which was 10% higher than that induced by the single promoter PP43. Similar results were observed between the dual-promoter PBcaprE-PBcaprE and the single promoter PBcaprE and the dual-promoter PgsiB-PgsiB and the single promoter PgsiB. However, the strength of the dual-promoter containing two PHpaII was 1.8-fold higher than that of the single promoter. The two promoters PP43 and PHpaII exhibited higher promoter activity for NK expression than that of the other promoters. We further carried out the experiments of arranging PHpaII and PP43 by combining three or four promoters in tandem. As shown in Table 2, our results indicated that the NK expression level was not associated with the numbers of tandem repeats of the promoters. The NK production under the control of PP43-PP43 was increased by 11.9% compared with that promoted by PP43, and the NK production mediated by PP43-PP43-PP43 increased by 39.4% compared with that promoted by PP43-PP43. However, the NK expression level increased by only 1.7% when promoted by PP43-PP43-PP43-PP43. Furthermore, NK production decreased under the control of four PHpaII in tandem compared with the expression controlled by three tandem promoters. The results were in agreement with studies that suggested that the length of the promoter affects its expression activity [35]. Although the cooperation mechanism of the tandem promoters was not clear, the increased production of NK suggested that this strategy of gene expression based on tandem promoter is an effective way to improve promoter activity.

The core region of a promoter plays an important role in regulating transcription initiation and is the minimal portion of a promoter that is required to properly initiate transcription [36]. To understand the effect of the length of repetitive whole-sequence promoters containing PP43 or PHpaII in tandem on the expression level of NK, a series of promoters with core-region repeats (nCPP43 and nCPHpaII) were constructed. The whole sequence of PHpaII is 284 bps; however, the core-region sequence of PHpaII is only 31 bps. The NK production mediated by 2PHpaII and 2CPHpaII almost reached the same level, which suggested that the core region of PHpaII could efficiently initiate the NK overexpression. However, it was unexpected that the strength of 3CPHpaII for NK expression was 35.2% lower than that of 3PHpaII. Further studies will be needed to explore the difference between the whole sequence and the core regions of PHpaII for the level of gene expression. In addition, the whole sequence of PP43 is 300 bps, and the core region of PP43 is 29 bps. The NK expression mediated by the whole sequence of PP43 in tandem increased to that mediated by 4PP43. The NK production that was initiated by core promoters of PP43 in tandem gradually increased as the number of core regions increased. It was found that both strong promoters, PP43 and PHpaII, have distinct characterization and differential expressions of NK. The analysis of the expression level of NK induced by more core regions of PP43 in tandem will be carried out.

Obviously different effects on NK production are caused by different arrangements in the dual-promoter system. The promoter is recognized by the σ factor of RNA polymerase to initiate gene transcription. Several σ factors have been defined in B. subtilis. It has been reported that σA- and σB-promoters can function cooperatively. The promoter synergism resulting from the double promoters was found only when the σB-promoter was located upstream of the σA-promoter, and the expression level of reporter gene was severely reduced by switching the locations of the σA- and σB-promoters [37]. Since PgsiB is σB-dependent (Additional file 1: Table S1), NK production promoted by PgsiB-PHpaII (164.9 ± 3.0 FU/ml) compared with that by PHpaII (110.8 ± 3.6 FU/ml) and that by PHpaII-PgsiB (0 FU/ml), suggested that PHpaII might be a σB-dependent promoter. Similar phenomena were observed in the results of NK expression mediated by PBcaprE-PHpaII (175.5 ± 5.0 FU/ml) and PHpaII-PBcaprE (0 FU/ml), by PluxS-PHpaII (77.5 ± 4.0 FU/ml) and PHpaII-PluxS (0 FU/ml), predicting that PluxS and PBcaprE are σB-dependent promoters. Whereas PyxiE is σA-dependent (Additional file 1: Table S1), results of NK production promoted by PHpaII-PyxiE (166.7 ± 2.5 FU/ml), compared with that by PyxiE-PHpaII (0 FU/ml) and that by PyxiE (20.2 ± 2.0 FU/ml), suggested that PHpaII might also be recognized by σA RNA polymerase. Therefore, promoters PHpaII and PP43 might be recognized by both σA and σB RNA polymerases. Our results showed that the NK expression that was promoted by the dual-promoter system makes a large difference, which could be due to the synergistic effect of the double promoters.

Studies have shown that triple-promoters could markedly increase the expression level of heterogeneous genes [29, 38]. We operated by combining both strong promoters in the form of three promoters in tandem. Eight strains harboring a triple-promoter system containing PHpaII and PP43 were generated, from which the NK production showed different levels. Among these 8 strains, one strain harboring the plasmid pSG-PHpaII-PP43-PP43 lost the ability to express NK, and one strain harboring the plasmid pSG-PP43-PHpaII-PHpaII exhibited low activity of NK expression (47.5 ± 3.1 FU/ml). The other six strains harboring the plasmid containing a triple-promoter exhibited relatively high production of the secreted NK, and the NK expression of four strains were higher than 200 FU/ml. The growth curves of strains containing triple-promoters were approximately the same (Additional file 1: Figure S2), and these results confirmed that the expression cassettes, but not the cell numbers, caused the different levels of NK production with different promoters. On account of the RNA polymerase gene transcription mechanism under the promoter action being very complex, the problem of how to produce this synergy has yet to be further studied. In this study, the highest NK production was mediated by a triple-promoter PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43 and achieved 264.2 ± 7.0 FU/ml, which is much higher than that reported in previous studies [39, 40]. This strain is a potential strain for the industrial production of NK. In addition, the high yield of NK could promote its application in medicine and in supplementary nutrition. A series of plasmids for NK expression in B. subtilis were constructed in this study, and they have great potential to be used for NK expression or the expression of other genes in industrial applications. The results of the various initial activities of multiple tandem promoters for NK expression also provide additional information on the synergistic interaction of promoters.

Conclusions

In this study, we generated and characterized the secretory expression of NK under the control of different promoters, including six single promoters and a series of promoters with the whole sequence or core regions in tandem. The expression level of NK mediated by one of these different promoters led to a remarkable difference in B. subtilis WB800. Among the six single promoters, NK production mediated by PHpaII and PP43 exhibited a higher level than the others. The arrangement of these promoters in tandem produced various effects on NK expression. We successively used the triple-promoter PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43 to increase the production of NK to 264.2 ± 7.0 FU/ml in B. subtilis WB800, which was the highest expression level ever reported. Our study provided an efficient way to increase NK production in Bacillus subtilis based on tandem promoters.

Materials and methods

Plasmids, strains and growth conditions

The plasmid pMA0911-pro-NK, an E. coli/B. subtilis shuttle plasmid with the HpaII promoter and wapA signal peptide, was used to clone and express NK. E. coli JM109 served as a host for cloning and plasmid preparation. B. subtilis WB800 is deficient in eight extracellular proteases and was used as a host for the NK expression. Bacillus subtilis 168 (B. subtilis 168) containing the promoter (PP43) was stored in our laboratory. Transformants were selected on LB agar (0.5% yeast extract, 1% tryptone, 1% NaCl and 2% agar), supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin for E. coli JM109 or 50 μg/mL kanamycin for B. subtilis WB800. E. coli JM109 was cultivated in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin. B. subtilis WB800 was incubated in TB medium (2.4% yeast extract, 1.2% tryptone, 0.4% glycerol, 17 mM KH2PO4, and 72 mM K2HPO4) additionally containing 0.02% CaCl2 and 50 μg/mL kanamycin. All of the strains were cultivated at 37 °C under shaking conditions at 200 rpm. Cell densities were measured using a UV-1800/PC spectrophotometer (MAPADA Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Construction of recombinant plasmids

Primers used in this study were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. and are listed in Table 3. A deficiency of the promoter PHpaII from the plasmid pMA0911-pro-NK was carried out following megaprimer PCR of the entire plasmid (MEGAWHOP) [41, 42] using primers P0-F and P0-R. The PCR product was digested by DpnI, and the resulting plasmid was transformed into JM109 to yield plasmid pSG-pro-NK without a promoter (Table 1).

Table 3.

Oligodeoxynucleotides used in this study

| Primers | Sequence (5′-3′) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| P0-F | GGCAAGGGTTTAAAGGTGGAGATTTTTTGAGTGTCGACATGAAAAAAAGAAAGAGGCGAAAC | Upstream for pMA0911-wapA-pro-NK construction |

| P0-R | CCTTTTAAAGTTTCGCCTCTTTCTTTTTTTCATGTCGACACTCAAAAAATCTCCACCTTTAAACC | Downstream for pMA0911-wapA-pro-NK construction |

| P1 | GGCAAGGGTTTAAAGGTGGAGATTTTTTGAGTTGATAGGTGGTATGTTTTCGCTTGAAC | Upstream of PP43 |

| P2 | CCTTTTAAAGTTTCGCCTCTTTCTTTTTTTCATGTCGACGTGTACATTCCTCTCTTACCTATAATGG | Downstream of PP43 |

| P3 | GGCAAGGGTTTAAAGGTGGAGATTTTTTGAGTTGCCGAATTCCATGAACGAGACTTAAAACG | Upstream of PBcaprE |

| P4 | CCTTTTAAAGTTTCGCCTCTTTCTTTTTTTCATGTCGACTCGGTTCCCTCCTCATTTTTATACCAACTTG | Downstream of PBcaprE |

| P5 | GGCAAGGGTTTAAAGGTGGAGATTTTTTGAGTGATCGTCACAATGCGCCATCAAACCG | Upstream of PluxS |

| P6 | CCTTTTAAAGTTTCGCCTCTTTCTTTTTTTCATGTCGACGGATCCCACTTTATGGACGCCGCAGTGTCTG | Downstream of PluxS |

| P7 | GGCAAGGGTTTAAAGGTGGAGATTTTTTGAGTCTATCGAGACACGTTTGGCTGG | Upstream of PgsiB |

| P8 | CCTTTTAAAGTTTCGCCTCTTTCTTTTTTTCATGTCGACTTCCTCCTTTAATTGGTGTTGGTTGTTGTATTC | Downstream of PgsiB |

| P9 | GGCAAGGGTTTAAAGGTGGAGATTTTTTGAGTGATCATTTAATTGAAGCGCGCGAAGC | Upstream of PyxiE |

| P10 | CCTTTTAAAGTTTCGCCTCTTTCTTTTTTTCATGTCGACGCTCTTCCCGCCTTTCGGACTGTGGGTGG | Downstream of PyxiE |

| P11 | GGGACAGGTAGTATTTTTTGAGAAGATCGTGTACATTCCTCTCTTACCTATAATGG | Downstream for PP43-PHpaII |

| P12 | GGCAAGGGTTTAAAGGTGGAGATTTTTTGAGTGATCTTCTCAAAAAATACTACCTGTCCC | Upstream of PHpaII |

| P13 | GGGACAGGTAGTATTTTTTGAGAAGATCTAAATCGCTCCTTTTTAGGTGGCACAAATGTG | Downstream or PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43 |

Note: Homology arms of targeting vectors for gene insertions were underlined

The promoter P43 gene was cloned from the genomic DNA of B. subtilis 168 with primers P1 and P2. The amplified product was cloned into pSG-pro-NK by the MEGAWHOP protocol, yielding plasmid pSG-PP43. The other single promoters (PBcaprE, PgsiB, PyxiE and PluxS) were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. and were employed to construct the plasmids pSG-PBcaprE, pSG-PgsiB, pSG-PyxiE and pSG-PluxS, respectively, using the same procedures as for pSG-PP43.

The six single promoters were further employed to construct 14 kinds of expression cassettes under the control of two promoters in tandem. The plasmid pSG-PP43-PHpaII was constructed by two steps. The fragment of P43 was amplified from pSG-PP43 using primers P1 and P11, and then the PCR product was inserted upstream of the promoter HpaII in pMA0911-pro-NK following the MEGAWHOP protocol, thereby yielding pSG-PP43-PHpaII. The same procedures were used to construct the other dual-promoter plasmids.

To construct the triple-promoter plasmid pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43, the fragment of HpaII was amplified from pMA0911-pro-NK with primers P12 and P13 and then was inserted into the front of the promoter PHpaII-PP43 in pSG-PHpaII-PP43 following the MEGAWHOP protocol. The other triple-promoter plasmids and two quad-promoter plasmids (pSG-4PHpaII and pSG-4PP43) were obtained after being treated in the same manner as for pSG-PHpaII-PHpaII-PP43.

The plasmids pSG-nCPX harboring the multiple tandem core promoter regions were synthesized by Shanghai RuiDi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. All plasmids were constructed and cloned in E. coli JM109 and were sequenced by Shanghai RuiDi Biological Technology Co., Ltd.

Overexpression of the recombinant nattokinase in B. subtilis WB800

Plasmid transformation was carried out according to the method as previously reported [43, 44]. A single colony was inoculated into 10 ml LB medium (including 50 μg/ml kanamycin) and were grown overnight at 37 °C, 200 rpm. The culture was transferred into 100 mL TB medium as a final OD600 value of 0.2(v/v), and then was cultivated at 37 °C for 84 h under a shaking condition at 200 rpm for the expression of NK. The supernatant was collected for the following research by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 5 min) at 4 °C.

Fed-batch cultivation in 5-L fermenter

Fed-batch cultivations were carried out in a 5-L bioreactor, and the initial medium was 2 L (2% glycerol, 2% soybean peptone, 0.1% NaH2PO4, 0.2% Na2HPO4, 0.02% CaCl2, and 0.05% MgSO4) containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The pre-inoculum culture was 50 mL TB medium including 50 μg/mL kanamycin, which was incubated at 37 °C under a shaking condition at 200 rpm. After 12 h, the culture was inoculated into the 5-L fermenter. The inoculation volume was 8%. The cultivated condition was maintained at 37 °C, and the dissolved oxygen (DO) was performed above 30% under the control of the inlet air and the exponential feeding of glycerol and soybean peptone. During the cultivation process, the pH was controlled at 7.0 through the automatic addition of 50% ammonium solution. Samples were taken every 2 h.

Fibrin plate analysis

A qualitative analysis of the fibrinolytic activity was carried out according to the fibrin plate method [45]. In brief, 10 ml agarose solution (1%) and 10 ml bovine fibrinogen solution (1.8 mg/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer) were incubated separately at 60 °C, and 10 U thrombin was added into the agarose solution and mixed. The agarose solution and fibrinogen were mixed, and the plate was put at room temperature for 2 h to form fibrin clots. Holes were made in the fibrin plate, and 40 μl enzyme was added in each hole. The fibrin plates were placed at 37 °C for 4 h to detect the fibrinolytic activity.

Fibrinolytic activity determination

The fibrinolytic activity was determined using the method described by the Japan Nattokinase Association (http://j-nattokinase.org/jnka_nk_english.html). In brief, 1.4 mL Tris-HCl (0.05 M, pH 8.0) and 0.4 mL fibrinogen solution (0.72%) were pre-incubated in a 37 °C water bath for 5 min. Thereafter, 0.1 mL thrombin solution was added, followed by the addition of 0.1 mL diluted sample after 10 min. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for an hour. Finally, trichloroacetic acid solution (0.2 M) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min to stop the reaction. The supernatant was transferred into a microtest tube after centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 10 min), and the absorbance of the supernatant at 275 nm was read and recorded. One unit (1 FU) was defined as the amount of the enzyme that increased the absorbance of the filtrate at 275 nm by 0.01 per minute. The analysis of fibrinolytic activity was independently carried out in triplicate, and the data are presented as the mean ± s.d.

SDS-PAGE analysis

Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 5 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer and protease inhibitor PMSF (phenylmethane sulphonyl fluoride). Then, the samples were heated at 100 °C for 5 min and were applied into 12% SDS-PAGE with 5% stacking gels. Finally, the gels were stained by Coomassie Blue R-250.

Additional file

Table S1 Characterization of single promoters used for the NK production. Figure S1 The growth curves of recombinant strains harboring different plasmids with a single promoter. Figure S2 The growth curves of recombinant strains containing a triple-promoter. (DOCX 297 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFE0127400), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JUSRP51713B), the national first-class discipline program of Light Industry Technology and Engineering (LITE2018–04), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, the 111 Project (No. 111–2-06) and National natural science foundation of China (3140078).

Availability of data and materials

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its supplementary information.

Abbreviations

- LB

Luria-Bertani medium

- NK

Nattokinase

- PBcaprE

aprE promoter

- PgsiB

gsiB promoter

- PHpaII

HpaII promoter

- PluxS

luxS promoter

- PP43

P43 promoter

- PyxiE

yxiE promoter

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SP

The wapA signal peptide

- TB

Terrific Broth medium

Authors’ contributions

ZL conceived the idea, designed this study, analyzed the data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. WZ participated in revising the manuscript. CG performed the experiments, including construction of plasmids and expression cassettes, overexpression and fermentation, analyzed the data. WC participated in the experiments of constructing expression systems. LZ participated in the fermentation experiment of nattokinase. ZZ conceived of the study, participated in its design, and coordination. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhongmei Liu, Phone: +86-510-85197551, Email: lmeimei1220@hotmail.com.

Wenhui Zheng, Email: 2311479882@qq.com.

Chunlei Ge, Email: 944453908@qq.com.

Wenjing Cui, Email: wjcui@jiangnan.edu.cn.

Li Zhou, Email: lizhou@jiangnan.edu.cn.

Zhemin Zhou, Email: zhmzhou@jiangnan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sumi H, Hamada H, Tsushima H, Mihara H, Muraki H. A novel fibrinolytic enzyme (nattokinase) in the vegetable cheese Natto; a typical and popular soybean food in the Japanese diet. Experientia. 1987;43(10):1110–1111. doi: 10.1007/BF01956052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujita M, Nomura K, Hong K, Ito Y, Asada A, Nishimuro S. Purification and characterization of a strong fibrinolytic enzyme (Nattokinase) in the vegetable cheese Natto, a popular soybean fermented food in Japan. Biochem Bioph Res Commun. 1993;197(3):1340–1347. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urano T, Ihara H, Umemura K, Suzuki Y, Oike M, Akita S, Tsukamoto Y, Suzuki I, Takada A. The profibrinolytic enzyme subtilisin NAT purified from Bacillus subtilis cleaves and inactivates plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(27):24690–24696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujita M, Hong KS, Ito Y, Fujii R, Kariya K, Nishimuro S. Thrombolytic effect of Nattokinase on a chemically-induced thrombosis model in rat. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18(10):1387–1391. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumi H, Hamada H, Nakanishi K, Hiratani H. Enhancement of the fibrinolytic activity in plasma by oral administration of nattokinase. Acta Haematol. 1990;84(3):139–143. doi: 10.1159/000205051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura T, Yamagata Y, Ichishima E. Nucleotide sequence of the Subtilisin NAT gene, aprN, of Bacillus subtilis (natto) Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56(11):1869–1871. doi: 10.1271/bbb.56.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yanagisawa Y, Chatake T, Chiba-Kamoshida K, Naito S, Ohsugi T, Sumi H, Yasuda I, Morimoto Y. Purification,crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction experiment of nattokinase from Bacillus subtilis natto. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2010;66(12):1670–1673. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110043137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Y, Bao W, Jiang S, Weng M, Jia Y, Yin Y, Zheng Z, Zou G. Directed evolution improves the fibrinolytic activity of nattokinase from Bacillus natto. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;325(2):155–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unrean P, Nguyen N. Metabolic pathway analysis and kinetic studies for production of nattokinase in Bacillus subtilis. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2013;36:45–56. doi: 10.1007/s00449-012-0760-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng ZL, Ye MQ, Zuo ZY, Liu ZG, Tai KC, Zou GL. Probing the importance of hydrogen bonds in the active site of the subtilisin nattokinase by site-directed mutagenesis and molecular dynamics simulation. Biochem J. 2006;395(3):509–515. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dabbagh F, Negahdaripour M, Berenjian A, Behfar A, Mohammadi F, Zamani M, Irajie C, Ghasemi Y. Nattokinase: production and application. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(22):9199–9206. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagarajan V. System for secretion of heterologous proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:214–223. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85021-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright AV, Leuschner RGK, Robinson TP, Hugas M, Cocconcelli PS, Richard-Forget F, Klein G, Licht TR, Nguyen-The C, Querol A, Richardson M, et al. Qualified presumption of safety (QPS): a generic risk assessment approach for biological agents notified to the European food safety authority (EFSA) Trends Food Sci Tech. 2010;21(9):425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2010.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohl S, Harwood CR. Heterologous protein secretion by Bacillus species: from the cradle to the grave. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2010;73:1–25. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(10)73001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zweers JC, Barak I, Becher D, Driessen AJM, Hecker M, Kontinen VP, Saller MJ, Vavrova L, Dijl JM. Towards the development of Bacillus subtilis as a cell factory for membrane proteins and protein complexes. Microb Cell Factories. 2008;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao L, Zhang RH, Peng Y, Zhang YZ. Highly efficient gene expression of a fibrinolytic enzyme (subtilisin DFE) in Bacillus subtilis mediated by the promoter of alpha-amylase gene from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Biotechnol Lett. 2004;26(17):1365–1369. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000045634.46909.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu XC, Lee W, Tran L, Wong SL. Engineering a Bacillus subtilis expression-secretion system with a strain deficient in six extracellular proteases. J Bacteriol. 1991;173(16):4952–4958. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.4952-4958.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phuong ND, Jeong YS, Selvaraj T, Kim SK, Kim YH, Jung KH, Kim J, Yun HD, Wong SL, Lee JK, Kin H. Production of XynX, a large multimodular protein of Clostridium thermocellum, by protease-deficient Bacillus subtilis strains. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;168(2):375–382. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9781-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye RQ, Kim JH, Kim BG, Szarka S, Sihota E, Wong SL. High-level secretory production of intact, biologically active staphylokinase from Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;62(1):87–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19990105)62:1<87::AID-BIT10>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durban MA, Silbersack J, Schweder T, Schauer F, Bornscheuer UT. High level expression of a recombinant phospholipase C from Bacillus cereus in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74(3):634–639. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0712-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen TT, Quyen TD, Le HT. Cloning and enhancing production of a detergent- and organic-solvent-resistant nattokinase from Bacillus subtilis VTCC-DVN-12-01 by using an eight-protease-gene-deficient Bacillus subtilis WB800. Microb Cell Factories. 2013;12:79. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu SM, Feng C, Zhong J, Huan LD. Enhanced production of recombinant nattokinase in Bacillus subtilis by promoter optimization. World J Microb Biotechnol. 2010;27(1):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s11274-010-0432-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang AL, Liu H, Yang MM, Gong YS, Chen H. Assay and characterization of a strong promoter element from B. subtilis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li W, Li HX, Ji SY, Li S, Gong YS, Yang MM, Chen YL. Characterization of two temperature-inducible promoters newly isolated from B. subtilis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358(4):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang M, Zhang W, Ji S, Cao P, Chen Y, Zhao X. Generation of an artificial double promoter for protein expression in Bacillus subtilis through a promoter trap system. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han L, Suo F, Jiang C, Gua J, Li N, Zhang N, Cui W, Zhou Z. Fabrication and characterization of a robust and strong bacterial promoter from a semi-rationally engineered promoter library in Bacillus subtilis. Process Biochem. 2017;61:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng J, Guan C, Cui W, Zhou L, Liu Z, Li W, Zhou Z. Enhancement of a high efficient autoinducible expression system in Bacillus subtilis by promoter engineering. Protein Expres Purif. 2016;127:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guan C, Cui W, Cheng J, Zhou L, Liu Z, Zhou Z. Development of an efficient autoinducible expression system by promoter engineering in Bacillus subtilis. Microb Cell Factories. 2016;15:66. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0464-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widner B, Thomas M, Sternberg D, Lammon D, Behr R, Sloma A. Development of marker-free strains of Bacillus subtilis capable of secreting high levels of industrial enzymes. J Ind Microbiol Biot. 2000;25(4):204–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang HK, Jang JH, Shim JH, Park JT, Kim YW, Park KH. Efficient constitutive expression of thermostable 4-a-glucanotransferase in Bacillus subtilis using dual promoters. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;26:1915–1918. doi: 10.1007/s11274-010-0351-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan C, Cui W, Cheng J, Liu R, Liu Z, Zhou L, Zhou Z. Construction of a highly active secretory expression system via an engineered dual promoter and a highly efficient signal peptide in Bacillus subtilis. New Biotechnol. 2016;33:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang K, Su L, Duan X, Liu L, Wu J. Highlevel extracellular protein production in Bacillus subtilis using an optimized dualpromoter expression system. Microb Cell Factories. 2017;16:32. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okegawa Y, Motohashi K. Expression of spinach ferredoxin-thioredoxin reductase using tandem T7 promoters and application of the purified protein for in vitro light-dependent thioredoxin-reduction system. Protein Expres Purif. 2016;121:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blazeck J, Alper HS. Promoter engineering: recent advances in controlling transcription at the most fundamental level. Biotechnol J. 2013;8:46–58. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yue X, Cui X, Zhang Z, Hu W, Li Z, Zhang Y, Li Y. Effects of transcriptional mode on promoter substitution and tandem engineering for the production of epothilones in Myxococcus xanthus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:5599–5610. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M, Wang J, Geng Y, Li Y, Wang Q, Liang Q, Qi Q. A strategy of gene overexpression based on tandem repetitive promoters in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Factories. 2012;11:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phanaksri T, Luxananil P, Panyim S, Tirasophon W. Synergism of regulatory elements in sigma(B)- and sigma(a)-dependent promoters enhances recombinant protein expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2015;120(4):470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei WZ, Xiang H, Tan HR. Two tandem promoters to increase gene expression in Lactococcus lactis. Biotechnol Lett. 2002;24(20):1669–1672. doi: 10.1023/A:1020653417455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suwanmanon K, Hsieh PC. Isolating Bacillus subtilis and optimizing its fermentative medium for GABA and nattokinase production. Cyta-J Food. 2014;12(3):282–290. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2013.848472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei X, Zhou Y, Chen J, Cai D, Wang D, Qi G, Chen S. Efficient expression of nattokinase in Bacillus licheniformis: host strain construction and signal peptide optimization. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42(2):287–295. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyazaki K, Takenouchi M. Creating random mutagenesis libraries using megaprimer PCR of whole plasmid. BioTechniques. 2002;33(5):1033–1034. doi: 10.2144/02335st03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyazaki K. MEGAWHOP cloning: a method of creating random mutagenesis libraries via megaprimer PCR of whole plasmids. Methods Enzymol. 2011;498:399–406. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385120-8.00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J. Requirements for transformation in Bacillus Subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1961;81(5):741–746. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.741-746.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bott KF, Wilson GA. Development of competence in the Bacillus subtilis transformation system. J Bacteriol. 1967;94(3):562–570. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.3.562-570.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weng M, Zheng Z, Bao W, Cai Y, Yin Y, Zou G. Enhancement of oxidative stability of the subtilisin nattokinase by site-directed mutagenesis expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794(11):1566–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Characterization of single promoters used for the NK production. Figure S1 The growth curves of recombinant strains harboring different plasmids with a single promoter. Figure S2 The growth curves of recombinant strains containing a triple-promoter. (DOCX 297 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its supplementary information.