Abstract

Sexual infidelity plays a significant role in the high rate of spousal transmission of HIV in Cambodia. The sexual beliefs and attitudes of a person begin in childhood and are developed through multiple chains in early adolescence, affecting his or her future sexual behavior and future incidence of HIV. A deeper understanding of the perspectives of adolescents regarding infidelity is critical to effective HIV prevention efforts during adulthood. Using a descriptive qualitative approach, this study explored the perceptions of male adolescents regarding male infidelity. Through the thematic analysis method, themes and subcategories were developed from the responses of 48 male high school students from three provinces. Majority of the participants (n = 33) were found to have liberal attitudes not only toward male infidelity but also toward the high possibility of their own future infidelity (n = 14). Almost 45% (n = 21) of the participants explained that men would fulfill their sexual desires outside, such as in karaoke, when their wives are unable to have sex with them. Participants believed it annoying for men to disclose their extramarital activities to their wives. The study concluded that the participants hold accepting perceptions about infidelity; they are part of the HIV problem and must be part of the solution. Educators and counselors need to deliver age-appropriate, scientifically correct, and culturally relevant messages about sexual health and HIV prevention to growing adolescents.

Keywords: Cambodia, adolescents, males, infidelity

Although monogamy and sexual exclusivity are the expressed cultural norms of a great majority of people, infidelity is widespread around the world (Butovskaya et al., 2014). Infidelity not just occurs with deleterious effects on couples’ relationships but also affects the health of the individuals in the relationship (Shrout & Weigel, 2018). It has been a powerful factor in the diffusion of the HIV pandemic in many parts of the world (Coma, 2013; Ravikumar & Balakrishna, 2013), including Cambodia.

In Cambodia, HIV/AIDS is spread mainly through heterosexual contact, especially through men engaging in unsafe sexual behaviors with women in brothels or in sexual entertainment establishments (World Health Organization [WHO], 2011). Not only are unfaithful husbands at direct risk of exposure to HIV, but the primary partners of these individuals are also at a high indirect risk of infection (Fals-Stewart et al., 2003). Spousal intercourse remains the primary route of HIV transmission in Cambodia, mainly from husband to wife (48%; National AIDS Authority, 2015). Men, compared to women, in Cambodia have more favorable attitudes toward infidelity; male infidelity is more common and is viewed as less of a threat to marriage (Yang, Wojnar, & Lewis, 2015). A Cambodian woman’s status is based on her loyalty to her husband, and retaining this status warrants overlooking a partner’s infidelity (Yang & Thai, 2017).

Knowledge of the factors associated with infidelity is necessary if appropriate interventions are to be undertaken to slow the spread of HIV. In Cambodia, behind the remarkably high prevalence of high-risk behaviors of young men are the various socioeconomic factors such as urban dwelling, being employed, being out of school, and living away from parents as well as the health-risk behavior factors like alcohol use and substance abuse (Yi et al., 2014). Breadwinner husbands (Munsch, 2018), men perceiving multiple sex partners as a key component of good health and peer pressure (Macia, Maharaj, & Gresh, 2011), remarriage, high income, alcohol consumption, and older age (Mtenga, Pfeiffer, Tanner, Geubbels, & Merten, 2018) correlate to male infidelity in different parts of the world. In one study, one third of Nigerian husbands recalled resorting to extramarital affairs to satisfy their unmet sexual need during their spouse’s pregnancy (Onah, Iloabachie, Obi, Ezugwu, & Eze, 2002). In rural Tanzania, the desire to prove masculinity and strong beliefs that men shall dominate women were reported as some of the factors influencing male infidelity (Mtenga et al., 2018), while work-related mobility was the major reason cited in another study (Smith, 2007). While a substantial proportion of women remain unaware of their risk because of false beliefs regarding their supposedly monogamous relationship (Essien, Meshack, Peters, Ogungbade, & Osemene, 2005), the majority of men who engage in extramarital affairs do not disclose this information to their spouses (Schmitt, 2003). This dual situation increases the risk of HIV among people.

The theory of planned behavior posits that an individual’s behavior is predicted by his or her intentions, attitudes toward behaviors, and perceived social norms (Ajzen, 1991) and that these attitudes result from social learning (Karimi & Saffarinia, 2005). One’s sexual behaviors are also influenced by one’s personal attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and desires (Arbuthnott, 2009; Rahimi-Naghani et al., 2016). Such sexual beliefs and attitudes begin in childhood and are developed over the course of the transition to adulthood, affecting individuals’ future sexual behavior (Kouta & Tolma, 2008) and likely influencing the future incidence of HIV. Adolescents should be an important focus of HIV research and HIV-preventive interventions. A deeper understanding of the perspectives of adolescents regarding infidelity is critical to effective HIV prevention efforts during adulthood (Yang, Lewis, & Wojnar, 2016).

Although the perceptions of infidelity of married adults and older adolescents in dating relationships have been well documented (Baranoladi, Etemadi, Ahmadi, & Fatehizade, 2016; Jahan et al., 2017; Kouta & Tolma, 2008), studies on the perspectives of unmarried adolescents regarding infidelity in marriage remain scant. Previously, the present research team investigated the perspectives of Cambodian adolescent women on male infidelity (under review). Many participants in that study were accepting of male infidelity and expected such behaviors in future husbands. Cambodian adolescent women perceived male sexual dominance as normal and justified separations caused by work-related mobility as fodder for male infidelity. The prior study on Cambodian adolescent women concluded that adolescent women in Cambodia are having HIV-vulnerable perceptions that increase their risk of HIV infection. Cambodian boys might have less generalized attitudes and beliefs regarding their infidelity or male infidelity in society. Cambodia’s rural adolescents’ comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS and its prevention is significantly lower than that of urban adolescents (National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health, & ICF International, 2015). Thus, there is a need to understand rural adolescent men’s perceptions and beliefs regarding infidelity, which may elicit particular sexual behaviors that might put them and their partners at risk of HIV infection in adulthood. Specifically, this study aimed to explore what rural Cambodian adolescents think about (a) men soliciting extramarital sex, (b) own future infidelity, (c) when wife is inaccessible to husband for sex, and (d) wife’s desire to know about husband’s extramarital behavior. The findings could provide valuable insights into early HIV prevention and program development that enhance young males’ knowledge of safe sexual practices and attitudes during their transition into adulthood.

Methods

Theoretical Background

The present study is an expanded one of the findings of an evidence-based model of HIV transmission from husbands to wives in Cambodia (Yang et al., 2016). Yang et al. (2016) developed the model through a systemic review of literature, professional publications, policy reports, and referential books related to HIV transmission within marriage in Cambodia along with data interpreted from interviews of Cambodian women who were infected with HIV by their spouses. In the evidence-based model, the two main social processes and culturally embedded mechanisms reported by Cambodian adult women that influence HIV transmission in marital relationships were as follows: first, a husband’s involvement with commercial sex workers and second, unprotected sex between an HIV-positive husband and his uninfected wife. Under these two mechanisms, participants in the model stated that men have stronger sexual desire and can have sex with other women if wives are not available for sex, husbands are trusted to be faithful, and women stay unaware of their husbands’ infidelity. A phenomenological study has recommended to understand adolescents’ perspectives and beliefs on marriage, sex, and infidelity in order to address the importance of attitudes on infidelity for effective HIV prevention during the transition to adulthood (Yang et al., 2015). The present study investigated the thoughts of adolescent men regarding the above-mentioned socially and culturally embedded factors of HIV transmission, and the model informed the current study’s aims and the associated interview questions (refer Table 1). The four study aims [objectives] were to explore what adolescent men in rural Cambodia think about (a) men soliciting extramarital sex, (b) own future infidelity, (c) when wife is inaccessible to husband for sex, and (d) wife’s desire to know about husband’s extramarital behavior.

Table 1.

Interview Questions.

| Category in Yang’s Model | Aims: To Understand the Perspectives of Adolescents on | Interview Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Husband’s involvement with commercial sex workers | Men soliciting extramarital sex | What do you think about Cambodian men going out for sex with other women? |

| Own future infidelity | How do you take it of yourself going out for sex even after marriage? | |

| When wife is inaccessible to wife for sex | According to your beliefs, what do you think one should do when one’s wife is not available for sex? | |

| Unprotected sex between HIV-positive husband and his uninfected wife | Wife’s desire to know about her husband’s sex behavior outside of marriage | In your thinking, how is it for a wife to be aware of her husband’s sex behavior outside of marriage? |

Study Setting and Participants

A qualitative, descriptive method guided the present study because it allows to make sense of, or interpret, social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as its participants feel it or live it in their natural settings (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008). Three rural provinces, namely, Koh Kong, Kampong Cham, and Kampong Chhnang were selected through convenient sampling, and sample recruitment occurred from three high schools, one from each province, from July 2017 to August 2017. The eligibility criteria for participants were unmarried men born in Cambodia, between 18 and 19 years of age, and in their third year of high school. The study was approved by Chonbuk National University Institutional Human Subjects Review Committee (2017-06-014-002) and the Cambodia Ethics Committee for Health Research of the Ministry of Health.

Interview Questions

Semistructured interview questions were asked to explore the views of the participants. Based on evidence-based model (Yang et al., 2016), four broad questions were devised (Table 1). The research guiding questions were “What do you think about Cambodian men having sex with other women?”; “How do you take it of yourself going out for sex even after marriage?”; “According to your beliefs, what do you think one should do when one’s wife is not available for sex?”; and “In your thinking, how is it for a wife to be aware of her husband’s extra-marital sex behavior?” Probing questions (e.g., “Will you explain more about . . .?”) were posed whenever necessary. Sociodemographic information was collected through a questionnaire developed by the authors. The research questions were similar to those used in a study (under review) on Cambodian adolescent women on the same issue. Before the interviews, the participants were assured that there were no right or wrong answers and that the researchers were only interested in their viewpoints on each question.

Data Collection

The research team consisted of two non-native females (senior and first authors) and one native male. In order to standardize the interview, the team members underwent 2 days of training on research aims, interview techniques, and procedures with the senior author. Initially, a document with details on study aims, research process, and interview questions was submitted to the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport (MoEYS) Cambodia. Upon approval from the Ministry, study purpose, eligibility criteria, and sample participation process were discussed in detail with high school principals and permission was requested to recruit students. With their permission, the third-year male students were approached after their class hours by the native team member of the study group. The potential participants were briefed about the study goals and procedures and were assured that their participation was voluntary. An interview was scheduled for the interested students.

All interviews were conducted in local Khmer language, and the native male team member (a PhD scholar majoring in nursing, with extensive knowledge and experience conducting qualitative interviews) assisted in all interviews as a Khmer/English interpreter. Since the interview topic was highly sensitive, rapport was established with the participants at the beginning of the interview by introducing topics, the study’s significance, the importance of participants’ responses, and the written informed consent assuring their privacy and confidentiality. Privacy was maintained by conducting interviews in a school-provided classroom with closed doors and windows. Participants were told that they could terminate the interview at any time. All interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ permission. Each interview lasted about 50 to 85 min. A total of 60 students (20 from each school) were approached of whom 12 (20%) rejected; 48 respondents were enrolled, although saturation was achieved after 43 respondents. Finally, $5 USD in a sealed envelope was provided to each interviewee as incentive for participation.

Data Management and Analysis

All interviews were conducted in Khmer, transcribed verbatim by a college student majoring in nursing, and translated into English by the same native male interpreter who assisted with the interviews. To ensure further accuracy, 10 transcripts out of 48 (20.83%) were retranslated by a second translator, a native speaker working as an English tutor. The interpreter, translator, and transcriptionist all signed confidentiality agreements assuring the confidentiality of the participants’ information. Accuracy was confirmed through thorough revisions and frequent discussions on the ambiguities between the two versions among the translator and research team members. The text data were managed using the ATLAS.ti 6.0 program.

Thematic analysis, a method to understand patterns within qualitative data, was applied to analyze and interpret the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Six processes were followed: (a) The transcripts were read repeatedly to become familiar with the data; (b) the important features of the data were presented by generating codes; (c) appropriate themes were constructed and the related codes were clustered; (d) the proper matching of potential themes in relation to the coded extracts and data was checked; (e) each theme was provided with clear definitions and names; (f) and a review of the interrelation of the themes, research questions, and literature review was conducted, and an analytical report was produced.

Study Rigor

Study rigor was established by the careful monitoring of data quality throughout the interview, transcription, and translation processes. The transcripts were double-checked and verified against the audio recordings by the translator for accuracy. The trustworthiness of the study findings was achieved through peer debriefing and maintaining of an audit trial (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Ongoing reviews and discussions occurred in face-to-face meetings with all authors, which aided in interpretation, consensus, and confirmation of study findings. For privacy, pseudonyms and code numbers were assigned to all participant-related information.

Results

The median participant age was 18.01 years (range 18–19 years); most participants lived with their parents; five lived in rented accommodation; none smoked, and five drank alcohol; most followed Buddhism; and their average pocket money was $90.

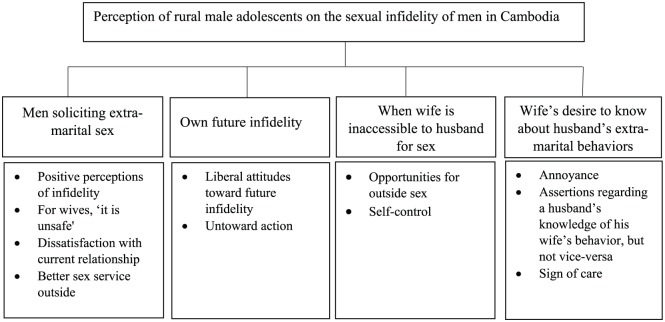

The themes and subcategories are outlined in Figure 1. Results are classified into four major themes: men soliciting extramarital sex; wife’s desire to know about husband’s extramarital behaviors; when wife is inaccessible to husband for sex; and own future infidelity. Further subcategories were arranged for the categories based on the participants’ answers.

Figure 1.

Perception of rural male adolescents on the sexual infidelity of men in Cambodia.

Men Soliciting Extramarital Sex

This theme relates to the participants’ outlook regarding sex-seeking extramarital behavior among married men. The possible reasons for such behaviors were also explained.

Positive perceptions of infidelity

More than half of the participants (n = 33) were in favor of male infidelity and did not perceive it as wrong. Participants believed that having sex with many women was not synonymous with being a bad person, associating multiple sex partners with men’s uncontrollable sexual desires. One stated:

I think he does it because he just likes it very much. It’s his uncontrollable desire. But that doesn’t mean he is a bad man. A good man can have such desires, and it is normal. (M2, 18 years)

For wives, “it is unsafe.”

A total of 12 participants had restrictive perceptions on infidelity, complaining that male infidelity meant cheating on one’s wife and family and being indecent. These participants were aware that infidelity was a risk factor for HIV transmission and a cause of family conflict. These participants added that perpetrators lose respect within their own family and the whole society. One participant said:

I don’t think it’s good to have extra-marital sex because we should always be honest to each other. When a husband cheats, there is the high chance of bringing STDs like HIV to the home, which is unsafe for the wife. In addition, when his wife comes to know about his behavior, domestic conflict will occur. Neighbors will start judging him badly. (M4, 19 years)

Dissatisfaction with current relationship

Thirty of the total participants considered the unmet needs and expectations of husbands within the marriage as a primary reason for male infidelity. Men who frequently fight within the home, who lack emotional support from wives, whose wives deny them sex for whatever reason, or who have stressful marriages would seek intimacy and comfort outside the marriage and this would likely result in extramarital relations. Twelve of the participants further raised concerns regarding imperfect wives, which they believed encourage husbands to seek out extramarital partners. Imperfect wife was defined as someone who stays ugly and is overweight, impolite, has no time for her husband because of overwork, whose beauty has faded after giving birth, or is ill and aged. One noted:

The main reason is his wife looking ugly as she grows older or after giving birth. She will not have enough time to groom herself, and sex service providers look far more beautiful than his wife at home. Also, if one’s wife is not polite to him, it will make him go away from her and search for another partner. (M32, 18 years)

Better sex service outside

Fourteen of the total participants perceived that outsiders were more beautiful and more skillful in terms of sexual satisfaction than wives would be and that routine sex with wives might be boring. For example, one man said,

I believe “no one eats sour soup every day.” This means a man always wants to try new and better soup, and same is for sex. Having sex with the same wife is so boring that a man will go with other women to change his taste. (M10, 20 years)

Moreover, the ease of affordable sex services in the community was considered as a perpetuating factor for infidelity. Access to money facilitates the expansion of male sexual networking with several women, as reported by the participants. One explained:

Because there is the availability of a better sex service just outside our door. And they are not expensive either. I heard that it costs approximately $10 to $50 for sex and massage. If it is so, then why would a man not go?!!!! (M9, 19 years)

Own Future Infidelity

One question asked about the participants’ possibility of and views on themselves seeking extramarital sex in their future marital life. Many justified that the accepting nature and culture of women made infidelity easier. Only a few perceived it as something wrong.

Liberal attitudes toward future infidelity

A total of 14 participants were optimistic about the possibility of their own future infidelity. These participants insisted that, culturally, females are and should be softhearted and forgiving and should not be overly concerned about their husbands’ behaviors. Participants identified themselves as the future breadwinners of the family and wives as individuals with no right to argue with husbands and who should simply forgive their husbands. Marrying another woman was expected to meet with anger and negative reactions from wives, but physical relations were not considered a sufficient reason for wives to question the participants. Like one said,

We (men) will be the head of the family, and we will handle all the financial stuffs of the house. Wives and children will be dependent on us. She cannot get angry with me. And if she earns too, she should still not be upset with her husband’s extra-marital sex because she is a woman. A woman should never try to be a man’s equal. No matter what, she is a woman. (M35, 19 years)

Untoward action

Eleven participants perceived infidelity as behavior they would forego in the future. These participants reasoned that they did not want their behavior to upset their future wife or to cause the HIV virus to enter the marriage. Another reason was that they had faced the negative consequences of infidelity in their family because their own fathers were unfaithful. One said:

I have been facing this problem since my childhood; my father has many sexual partners outside and is HIV positive. After seeing what my father has done to us and my mother, I am determined that I will not repeat my father’s mistake. I will not let my mind get diverted toward other women, will always consider my wife pretty, and will not fantasized about extra marital relations, never. (M27, 19 years)

When Wife is Inaccessible to Husband for Sex

The participants were asked what they thought a man should do when he has strong feelings for sex but that his wife was sexually unavailable. A mix of responses were reported; some said one should go outside, while others spoke of the need for self-control.

Opportunities for extramarital sex

Almost 45% (n = 21) of the participants explained that men will fulfill their sexual desires outside, such as in karaoke, when their wives were unable to have sex with them. There was no second thought among these participants.

I think he should have sex service from outside if his wife is not accessible because of illness, pregnancy, or menstruation. And there is nothing wrong with this. It is available in KTV. I know some men who do so and they said that it costs only around $10 to $15. (M41, 18 years)

Four out of these 21 participants who responded searching for another sex partner when the wife is not accessible for sex, however, emphasized the need for consciousness about preventing themselves from spreading STDs like HIV by using condoms while using sex services. One stated:

It is common for a man to go for extra-marital sex in such situations. But he should well protect himself from HIV by using condoms. (M32, 18 years)

Self-control

Only 12 of the total study sample reported that a man should be a morally responsible husband by practicing sexual abstinence in such situations. For them, doing so meant being respectful to the wife. Doing exercises, watching movies, and entertaining oneself in other ways were suggested by the participants as ways to reduce sexual cravings in such situations.

No matter the situation, he should control himself. We should not disrespect our wives. It is normal for human beings to have sexual cravings, but the important thing is whether you can control it for a short period. One can listen to music, do yoga, chat with friends, or go for movies in order to forget about that feeling. (M40, 18 years)

Wife’s Desire to Know About Husband’s ExtraMarital Behavior

The participants expressed their views on a wife’s desire to know about her husband’s extramarital behavior. Their views were divided into three categories: annoyance; assertions regarding a husband’s knowledge of his wife’s behavior, but not vice versa; and sign of care.

Annoyance

For 14 participants, a wife’s desire to learn of her husband’s extramarital behavior was a sign of mistrust and suspicion toward her husband. Such a desire of a wife was assumed to be highly disturbing and annoying. As one said, “Maybe because she is jealous of him or she does not trust him. She thinks that he is cheating on her by having an outside girlfriend. It is the disturbing nature of every wife” (M18, 21 years). Participants mentioned that men cannot enjoy their privacy when such things happen and that they would probably tell a lie if their wives asked. One claimed:

If my wife interrogates me like this, it will be too annoying. I will tell her a lie that I am with my friends or in a meeting. Like this, she will not know the truth, and if she does not know, there will be no trouble. (M35, 19 years)

Assertions regarding a husband’s knowledge of his wife’s behavior, but not vice versa

Meanwhile, five of those who were not keen about wives’ desire to know their husbands’ extramarital behavior explained that they would always want to know what their wives did outside and with whom. Men were explained to be more sexually relaxed but less trusting than their wives. One said:

I don’t want to let her know about my activities. Even if I have a partner outside, it is annoying if she knows about it. But yes, I would definitely want to know about her, where she is, why she is there, and with whom. I am afraid that she might have another man outside. (M19, 19 years)

Sign of care

Twenty of the total participants positively evaluated a wife’s desire to learn about her husband’s extramarital behavior and linked this to a woman’s love and care for her husband. Being members of the same family, it was supposed essential for couples to be completely transparent with each other. Wives would be worried about their husbands’ health and safety when they are outside, so husbands should be responsible by always letting their wives know what they are doing. Seven of those who perceived a wife’s desire to know about her husbands’ activities as notification of care even gave examples of their own fathers, sharing that because their fathers let their mothers know about all activities, they learned that they should do the same in the future. For example:

It is all about being caring and loving. It is not at all disturbing. Women try to confirm whether husbands are fine or not. People may think that she is being suspicious, but I take it as a sign of care. (M11, 18 years)

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, rural adolescent men’s insights regarding male infidelity have remained unexplored, and this study has tackled the issue in the Cambodian context.

The majority of the study (n = 30) participants argued that marital or sexual dissatisfaction influenced male infidelity, which was consistent with participants’ views from other studies (Rada, 2012). The participants placed the responsibility squarely on wives. According to them, any husband whose wife argues incessantly, denies sex, or is ugly, fat, or a workaholic might be motivated to engage in extramarital relations. As with men from other countries, physical attractiveness is heavily weighted by Cambodian men in both short- and long-term mates, as discussed in previous studies, while women place less emphasis on it (Lippa, 2009; Yang, Thapa, & Lewis, 2018). Satisfaction in marital life is seen as a strategy to reduce the incidence of infidelity in marriage (Olderbak & Figueredo, 2010); however, relationship quality and satisfaction are determined by the contributions of both the husband and wife (Allen et al., 2008). Adolescent men should be guided early on that not only are wives responsible for exercising control of their relationships, but husbands are also equally responsible for nurturing a happy married life. Young men should be prepared to respect the institution of marriage and to follow strategies such as being faithful to one person, controlling inevitable feelings of being attracted to others outside, and preserving faithfulness in marital relationships (Butovskaya et al., 2014).

The current study participants compared extramarital sex and routine sex with a wife, claiming superiority of the former. Participants considered outsiders to be more beautiful and more skillful in providing a variety of sexual pleasures, while routine sex with a wife was regarded as boring. Traditionally, Cambodian husbands seek sexual variety from commercial sex workers, which they believe could not be obtained from their wives at home while Cambodian wives identify sex with husbands as the duty of a wife and follow the tradition of pardoning their husbands’ infidelity and this phenomenon contributes to male infidelity and HIV transmission within marriage in Cambodia (Ramage, 2002; Yang, 2012). Cautionary messages from Cambodian adults to younger people—not to fall for the outside appearances of outsiders, beauty is not everything in marital life, and faithfulness is important in husband–wife relationship (Yang et al., 2018)—are indeed fundamental to have a happy and healthy marital relationship. Special training and counseling programs for women about the meaning of sex and an acknowledgment of various sex techniques and positions could be fruitful in long-term marital life (Yang et al., 2018).

A majority of 33 participants in this study perceived infidelity positively, associating it with men’s uncontrollable sexual urges and expressed liberal attitudes about their future infidelity. According to them, there is nothing wrong with a man having multiple sexual partners, even after marriage, and sex with casual partners is expected when a regular partner is deemed unavailable. This explanation constitutes with the “masculine” ideals and the deeply rooted social norms that permit Cambodian men to have multiple extramarital relations (Family Health International, 2002). In the past two decades, studies (e.g., Phan & Patterson, 1994; Yang et al., 2015) have consistently concluded that male infidelity is indeed common and is culturally tolerated and socially accepted in Cambodia. Comparing the current results with perceptions of sexual norms suggests that Cambodian adolescent men are following the deleterious social norms of infidelity and beliefs of masculine virility. Gender norms, masculine beliefs, and stereotypes, including notions of sexuality, have important implications for men’s sexual behavior. Such perceptions at an early age may lead to particular sexual behaviors, which put males and their primary partners at risk for HIV infection (Macia et al., 2011). HIV-infected Cambodian men have appealed for loyalty in marriage and have expressed regret for not doing so in the past, while HIV-infected women have urged children not to follow the same social norms traversed by older men, as this increases the risk of HIV (Yang et al., 2018). These messages might be useful in persuading younger generations remain aware about social, cultural, and familial embedded risk factors associated with HIV. Growing adolescents are often neglected in HIV/AIDS education campaigns in Cambodia (United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], & WHO, 2015), and this study shows that they are clearly at risk. Cambodian adolescents need to recognize fidelity as a major HIV prevention and marital stability strategy. School-based sexuality education is a cornerstone in reducing adolescents’ risky sexual behaviors and in promoting healthy sexual attitudes prior to the onset of sexual activity (Achora, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, Akpor, & Mashalla, 2018).

The findings revealed that the participants were nonchalant about their future infidelity because they were sure that their future wives would be permissive. Male infidelity was believed to be equally perpetuated by women because of women’s dependency on men for survival. Although women are aware of their partners’ extramarital behavior, they lack control in sexual matters and are expected to be submissive (Mbonu, Van den Borne, & De Vries, 2010). It has been argued that women’s economic vulnerability and dependency increase their susceptibility to HIV, as their ability to negotiate—including regarding sexual abstinence, condom use, and multiple partnerships, which shape their risk of infection—is restrained (Thapa, Yang, Kang, & Nho, 2019). Studies also advocate women’s economic independence as a major factor in promoting preventive HIV behaviors; women then become sufficiently confident in demanding condom use and negotiating safer sex because the potential loss of partners would not affect their ability to support themselves and their children (Dworkin, Kambou, Sutherland, Moalla, & Kapoor, 2009; Kim, Pronyk, Barnett, & Watts, 2008). Practical and sustainable income-generating training would also be effective for women and would minimize their economic dependency on men, thus making it more likely that they will negotiate safe sex with their husbands.

Consistent with the findings of other Cambodian studies, the present study respondents expressed the high possibility of extramarital intercourse in meeting their unmet sexual needs during their future wives’ pregnancy or any work-related mobility (Samnang et al., 2004; Sok et al., 2008; Sopheab, Fylkesnes, Vun, & O’Farrell, 2006). Samnang et al. (2004) identified that Cambodian fishermen who remained in port for more than 1 day had a significantly higher HIV prevalence (31.7%) than others (14.6%). Similarly, Sopheab et al. (2006) reported that travels exceeding 1 month in the past year was a strong independent contributing factor in extramarital sex among Cambodian men. Nigerian husbands also admitted to seeking extramarital sex during their wives’ pregnancy due to inaccurate beliefs about intercourse during pregnancy (Onah et al., 2002). In fact, as long as no health issues are involved, the recommendations and guidelines from health physicians are that cautious sexual intercourse during pregnancy is safe (Kontoyannis, Katsetos, & Panagopoulos, 2012). School health education must include education about sexual intercourse during pregnancy, and adolescents must be encouraged to visit antenatal care clinics with their future wives to discuss couple-related health issues or questions with a health-care professional (Onah et al., 2002). Youth-friendly and accessible counseling services may be effective in not only equipping the youth to make responsible choices for their own sexual lives and shaping healthy transitions into adulthood but also combating the HIV epidemic (Fonner, Armstrong, Kennedy, O’Reilly, & Sweat, 2014).

Seven participants in the present study recalled the experience of their parents’ infidelity, stating that they would not emulate their parents. Offspring witnessing parental infidelity are 2.5 times more likely, than their counterparts, to engage in infidelity themselves (Weiser & Weigel, 2017). The participants can also be categorized as risky because their parents would continuously attempt to communicate justifications about infidelity to minimize blame; children being raised with positive messages about infidelity, along with parental actions, internalize liberal beliefs about infidelity, increasing the likelihood of offspring infidelity (Thorson, 2014; Weiser & Weigel, 2017). The virtuous practice of discouraging infidelity among youth should continuously be promoted to help youth maintain healthy attitudes throughout their lives. Health officers should help parents negotiate infidelity experiences to reduce the likelihood of their children’s future infidelity (Weiser & Weigel, 2017). The influential role of parental infidelity on children in Cambodia merits further exploration. The social development model (SDM) suggests that families, schools, peer groups, and communities are fundamental units of socialization that determine youth activities and behaviors (Hawkins & Weis, 1985). Parents could create a friendly home environment to maintain lines of communication with their children about sexuality and gender equality may be beneficial at different stages during the child’s social and moral development (Kågesten et al., 2016).

Fourteen participants perceived wives’ desire to learn of their husbands’ extramarital behaviors with mistrust. This view appears to originate from cultural norms that expect Cambodian women to be modest and remain inattentive to men’s sexual relations (Saing, 2018). Poor communication related to sexual behaviors between couples is a major risk factor for HIV infection (Yang & Thai, 2017). Although husbands’ sex with multiple partners is a major source of HIV infection among Cambodian wives, virtuous wives are expected to remain quiet about their husbands’ sexual relations and to endure undesired sexual behaviors (Ramage, 2002; WHO, 2011). The present study findings suggest that culturally appropriate interventions could target adolescent men and women separately so as to create a safe communicating environment, transmit information about reproductive health, and facilitate sexual communication between couples in the future (Marlow, Tolley, Kohli, & Mehendale, 2010).

The majority of participants in the present study were found to be nonchalant about male infidelity, while adolescent women in the previous study (under review) were reported to be accepting of male infidelity; differences are minute when comparing these study findings to those from adult women in the evidence-based model (Yang et al., 2016). These similarities might be indicative of adolescents’ inclination to engage in extramarital affairs during adulthood, which could lead to further risk of HIV in Cambodia. This indicates that traditional, social, and cultural norms regarding male infidelity are deeply rooted in the country, irrespective of age and gender. The insights revealed in this study can inform the incorporation of several adjustments into existing or future HIV interventions, which will ultimately increase their effectiveness among growing Cambodian adolescents. While recognizing the importance for Cambodian youth to be aware of HIV and AIDS, MoEYS has closely cooperated and coordinated its program activities with international and local NGOs, National AIDS Authority (NAA), other line ministries, and the donor communities and has also mainstreamed HIV and AIDS in the education sector. They mainly focus on integrating HIV and AIDS in the national curriculum, providing training for preservice and in-service teachers and implementing Life Skills for HIV and AIDS Education (LSHE) program that targets the in-school and out-of-school youth. All these programs aim to provide the foundations to assist Cambodian youth in developing the values and norms that will allow them to generate and adopt behaviors that safeguard themselves and others from risky behaviors (MoEYS/ICHA, 2007). Other organizations like KHANA and Cambodian HIV/AIDS Education and Care (CHEC) are also working to ensure that youth are enriched with knowledge, motivated, and guided toward safe behaviors and attitudes in an effort to make them aware of harmful gender norms to ultimately prevent HIV transmission. However, there is a need to scale up these targeted interventions in the coming years, especially in the rural areas and ensure new and updated approaches to address sexual and reproductive health for the young population.

There are a few study limitations that must be considered. Sex-related behaviors and issues are rarely openly discussed in many parts of the world. Due to the sensitive nature of the questions asked, the results may be limited by the underreporting of participants. Also, the participants’ responses in face-to-face interviews might be socially desirable and norm driven (Hewett et al., 2008). In order to overcome the limitation of underreporting, all participants were encouraged to feel free to share their ideas, and a native male interviewer was assigned. Deeper explanations were also obtained with the help of probing questions. Convenience sampling method utilized in this study might have limited the transferability of the research findings.

Conclusion

The study concludes that the participants hold accepting perceptions about infidelity; they are part of the HIV problem and must be part of the solution. Their liberal attitudes toward infidelity reflects an HIV-vulnerable future. This study may facilitate preventive approaches to dealing with behaviors that may result in long-term negative consequences. Parents can act as role models by carrying a sense of responsibility to their families and by being faithful in the husband–wife relationship, which will eventually limit infidelity in their children. Teachers and counselors should educate and deliver age-appropriate, scientifically based, and culturally relevant messages about sexual health, HIV prevention, and impacts of sexual infidelity. High school curricula could be aimed at establishing gender role lessons pertaining to love and marriage and HIV; those not attending school should be reached through community-based awareness programs (Yang, 2012). The government should collaborate with schools, families, communities, health workers, and adolescents themselves to plan and develop appropriate programs that target adolescents. The media play a vital role in spreading knowledge on HIV and infidelity. Rural adolescents with limited access to media require alternative sources of information. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to implement national and multilevel youth-targeted interventional programs so that deep-rooted norms can be changed.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Global Research Network Program through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2016S1A2A2912566).

ORCID iD: Youngran Yang  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5610-9310

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5610-9310

References

- Achora S., Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G., Akpor O. A., Mashalla Y. J. S. (2018). Perceptions of adolescents and teachers on school-based sexuality education in rural primary schools in Uganda. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 17, 12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Allen E. S., Rhoades G. K., Stanley S. M., Markman H. J., Williams T., Melton J., Clements M. L. (2008). Premarital precursors of marital infidelity. Family Process, 47(2), 243–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuthnott K. D. (2009). Education for sustainable development beyond attitude change. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 10(2), 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Baranoladi S., Etemadi O., Ahmadi S. A., Fatehizade M. (2016). Qualitative evaluation of men vulnerability to extramarital relations. Asian Social Science, 12(7), 202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Butovskaya M., Nowak N. T., Weisfeld G. E., Imamoğlu O., Weisfeld C. C., Shen J. (2014). Attractiveness and spousal infidelity as predictors of sexual fulfillment without the marriage partner in couples from five cultures. Human Ethology Bulletin, 29(1), 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Coma J. C. (2013). When the group encourages extramarital sex: Difficulties in HIV/AIDS prevention in rural Malawi. Demographic Research, 28, 849–880. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. (2008). The landscape of qualitative research (Vol. 1). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin S. L., Kambou S. D., Sutherland C., Moalla K., Kapoor A. (2009). Gendered empowerment and HIV prevention: Policy and programmatic pathways to success in the MENA region. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51(Suppl 3), S111–S118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essien E. J., Meshack A. F., Peters R. J., Ogungbade G., Osemene N. I. (2005). Strategies to prevent HIV transmission among heterosexual African-American women. International Journal for Equity in Health, 4(1), 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W., Birchler G. R., Hoebbel C., Kashdan T. B., Golden J., Parks K. (2003). An examination of indirect risk of exposure to HIV among wives of substance-abusing men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 70(1), 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Health International. (2002). Strong fighting: Sexual behavior and HIV/AIDS in the Cambodian uniformed services. Retrieved from http://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/documents/FHI_2002_Cambodia_Sexual_Behavior_and_HIV_AIDS_in_the_Cambodian_Uniformed_Services.pdf

- Fonner V. A., Armstrong K. S., Kennedy C. E., O’Reilly K. R., Sweat M. D. (2014). School based sex education and HIV prevention in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 9(3), e89692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins J. D., Weis J. G. (1985). The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 6(2), 73–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett P. C., Mensch B. S., Ribeiro M. C. S. d. A., Jones H. E., Lippman S. A., Montgomery M. R., Wijgert J. H. H. M. v. d. (2008). Using sexually transmitted infection biomarkers to validate reporting of sexual behavior within a randomized, experimental evaluation of interviewing methods. American Journal of Epidemiology, 168(2), 202–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahan Y., Chowdhury A. S., Rahman S. M. A., Chowdhury S., Khair Z., Huq K. A. T. M. E., Rahman M. M. (2017). Factors involving extramarital affairs among married adults in Bangladesh. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 4(5), 1379–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Kågesten A., Gibbs S., Blum R. W., Moreau C., Chandra-Mouli V., Herbert A., Amin A. (2016). Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PloS one, 11(6), e0157805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi Y., Saffarinia D. (2005). Social psychology and attitude change energy consumers. Iranian Journal of Energy, 9(20), 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Pronyk P., Barnett T., Watts C. (2008). Exploring the role of economic empowerment in HIV prevention. AIDS, 22, S57–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontoyannis M., Katsetos C., Panagopoulos P. (2012). Sexual intercourse during pregnancy. Health Science Journal, 6(1), 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kouta C., Tolma E. L. (2008). Sexuality, sexual and reproductive health: An exploration of the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of the Greek-Cypriot adolescents. Global Health Promotion, 15(4), 24–31. doi: 10.1177/1025382308097695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry (Vol. 75). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lippa R. A. (2009). Sex differences in sex drive, sociosexuality, and height across 53 nations: Testing evolutionary and social structural theories. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(5), 631–651. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9242-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia M., Maharaj P., Gresh A. (2011). Masculinity and male sexual behaviour in Mozambique. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 13(10), 1181–1192. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.611537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow H. M., Tolley E. E., Kohli R., Mehendale S. (2010). Sexual communication among married couples in the context of a microbicide clinical trial and acceptability study in Pune, India. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(8), 899–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonu N. C., Van den Borne B., De Vries N. K. (2010). Gender-related power differences, beliefs and reactions towards people living with HIV/AIDS: An urban study in Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 10, 334. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport (MoEYS)/Interdepartmental Committee for HIV & AIDS (ICHA). (2007). HIV & AIDS in the Education Sector in Cambodia. Retrieved from https://hivhealthclearinghouse.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/Fact_Sheet_3_REVISED.pdf

- Mtenga S. M., Pfeiffer C., Tanner M., Geubbels E., Merten S. (2018). Linking gender, extramarital affairs, and HIV: A mixed methods study on contextual determinants of extramarital affairs in rural Tanzania. AIDS Research and Therapy, 15(1), 12. doi: 10.1186/s12981-018-0199-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch C. L. (2018). Correction: “Her support, his support: money, masculinity, and marital infidelity” American Sociological Review, 80(3):469–95. American Sociological Review, 83, 833–838. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Authority. (2015). Cambodia country progress report. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/KHM_narrative_report_2015.pdf

- National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health, & ICF International. (2015). Cambodia demographic and health survey 2014. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr312/fr312.pdf

- Olderbak S. G., Figueredo A. J. (2010). Life history strategy as a longitudinal predictor of relationship satisfaction and dissolution. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(3), 234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Onah H. E., Iloabachie G. C., Obi S. N., Ezugwu F. O., Eze J. N. (2002). Nigerian male sexual activity during pregnancy. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 76(2), 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan H., Patterson L. M. (1994). Men are gold, women are cloth: A report on the potential for HIV/AIDS spread in Cambodia and implications or HIV/AIDS education. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: CARE International. [Google Scholar]

- Rada C. (2012). The prevalence of sexual infidelity, opinions on its causes for a population in Romania. Revista de Psihologie, 58(3), 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi-Naghani S., Merghati-Khoei E., Shahbazi M., Farahani F. K., Motamedi M., Salehi M., … Hajebi A. (2016). Sexual and reproductive health knowledge among men and women aged 15 to 49 years in metropolitan Tehran. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(9), 1153–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage I. (2002). Strong fighting: Sexual behavior and HIV/AIDS in the Cambodian uniformed services. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: FHI. [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B. C., Balakrishna P. (2013). Discordant HIV couple: Analysis of the possible contributing factors. Indian Journal of Dermatology, 58(5), 405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saing R. (2018). Exploring sexual coercion within marriage in rural Cambodia (PhD dissertation). Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Samnang P., Leng H. B., Kim A., Canchola A., Moss A., Mandel J. S., Page-Shafer K. (2004). HIV prevalence and risk factors among fishermen in Sihanouk Ville, Cambodia. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 15(7), 479–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D. P. (2003). Universal sex differences in the desire for sexual variety: Tests from 52 nations, 6 continents, and 13 islands. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(1), 85–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout M. R., Weigel D. J. (2018). Infidelity’s aftermath: Appraisals, mental health, and health-compromising behaviors following a partner’s infidelity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(8), 1067–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. J. (2007). Modern marriage, men’s extramarital sex, and HIV risk in southeastern Nigeria. American Journal of Public Health, 97(6), 997–1005. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2006.088583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sok P., Harwell J. I., Dansereau L., McGarvey S., Lurie M., Mayer K. H. (2008). Patterns of sexual behaviour of male patients before testing HIV-positive in a Cambodian hospital, Phnom Penh. Sex Health, 5(4), 353–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopheab H., Fylkesnes K., Vun M. C., O’Farrell N. (2006). HIV-related risk behaviors in Cambodia and effects of mobility. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 41(1), 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa R., Yang Y., Kang J. H., Nho J.-H. (2019). Empowerment as a predictor of HIV testing among married women in Nepal. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. Advance online publication. doi:10.1097/JNC.0000000000000021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorson A. R. (2014). Feeling caught: Adult children’s experiences with parental infidelity. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 15(1), 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA, UNESCO & WHO. (2015). Sexual and reproductive health of young people in Asia and the Pacific: A review of issues, policies, and programs. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002435/243566E.pdf

- Weiser D. A., Weigel D. J. (2017). Exploring intergenerational patterns of infidelity. Personal Relationships, 24(4), 933–952. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2011). Health of adolescents in Cambodia. Manila, Philippines: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Retrieved from http://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/5254/Health_adolescents_KHM_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. (2012). HIV transmission from husbands to wives in Cambodia: The women’s lived experiences (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fd88/e7a7cc6cac04ce474a09328160e134672f1f.pdf

- Yang Y., Lewis F. M., Wojnar D. (2015). Life changes in women infected with HIV by their husbands: An interpretive phenomenological study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 26(5), 580–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Lewis F. M., Wojnar D. (2016). Culturally embedded risk factors for Cambodian husband-wife HIV transmission: From women’s point of view. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 48(2), 154–162. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Thai S. (2017). Sociocultural influences on the transmission of HIV from husbands to wives in Cambodia: The male point of view. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(4), 845–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Thapa R., Lewis F. M. (2018). “I am a good example”: Suggestions from HIV-infected Cambodians for preventing HIV infection in marital relationships. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 29(4), 592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Wojnar D., Lewis F. M. (2015). Becoming a person with HIV: Experiences of Cambodian women infected by their spouses. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(2), 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi S., Tuot S., Yung K., Kim S., Chhea C., Saphonn V. (2014). Factors associated with risky sexual behavior among unmarried most-at-risk young people in Cambodia. American Journal of Public Health, 2(5), 211–220. [Google Scholar]