Abstract

Background

Bacteria are widely used as hosts for recombinant protein production due to their rapid growth, simple media requirement and ability to produce high yields of correctly folded proteins. Overproduction of recombinant proteins may impose metabolic burden to host cells, triggering various stress responses, and the ability of the cells to cope with such stresses is an important factor affecting both cell growth and product yield.

Results

Here, we present a versatile plasmid-based reporter system for efficient analysis of metabolic responses associated with availability of cellular resources utilized for recombinant protein production and host capacity to synthesize correctly folded proteins. The reporter plasmid is based on the broad-host range RK2 minimal replicon and harbors the strong and inducible XylS/Pm regulator/promoter system, the ppGpp-regulated ribosomal protein promoter PrpsJ, and the σ32-dependent synthetic tandem promoter Pibpfxs, each controlling expression of one distinguishable fluorescent protein. We characterized the responsiveness of all three reporters in Escherichia coli by quantitative fluorescence measurements in cell cultures cultivated under different growth and stress conditions. We also validated the broad-host range application potential of the reporter plasmid by using Pseudomonas putida and Azotobacter vinelandii as hosts.

Conclusions

The plasmid-based reporter system can be used for analysis of the total inducible recombinant protein production, the translational capacity measured as transcription level of ribosomal protein genes and the heat shock-like response revealing aberrant protein folding in all studied Gram-negative bacterial strains.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12934-019-1128-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fluorescent proteins, Recombinant protein production, Synthetic biology, Metabolic engineering, Microbial cell factory

Background

Further advances in the field of recombinant protein production require continuous efforts concerning not only expression vector design but also rational genome engineering [1]. Typical host-related aspects affecting recombinant protein production are related to the availability of energy and protein synthesis components comprising amino acids, free ribosomal subunits and other translational factors. Limitations related to such host parameters are commonly observed as reduced cell growth, plasmid loss and poor production yields [1]. In many cases, though, it is difficult to predict and distinguish various host physiological effects, and there is a need for tools enabling high-throughput strain analysis in order to obtain more precise understanding of host-related responses related to overproduction of recombinant proteins [2, 3].

Depletion of amino acids is linked to the stringent stress response mediated by the guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) alarmone, which among others down-regulates transcription of ribosomal protein (r-protein) and rRNA operons [4]. Although its mode of regulation may differ among microbial species [5], in Gram-negative bacteria, ppGpp primarily interacts with RNA polymerase (RNAP), in synergy with the RNAP-binding transcriptional factor DksA, to directly affect transcription [6, 7]; and the ppGpp binding site regions are well conserved in representatives of the Gammaproteobacteria [8]. In Escherichia coli, overproduction of recombinant proteins can lead to formation of inclusion bodies if there is an imbalance between the rates of protein synthesis and folding. Consequently, a σ32-related heat shock-like response is induced, which results in upregulation of the heat-shock proteins such as the chaperone DnaK [9–11]. Analysis of the rpoH genes encoding homologs of σ32 protein from the Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria subgroups revealed sequence similarities that should reflect conserved function and regulation of σ32 in the heat-shock response [12]. These data are consistent with further observations that expression of σ32 homologs from Serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in E. coli mutant strain lacking its own σ32 leads to the transcriptional activation of the heat-shock genes from the start sites normally used in E. coli [13].

A reporter system for monitoring the heat-shock like response to recombinant protein production has been reported previously [11], as a σ32-dependent tandem promoter, Pibpfxs, generated by fusion of ibpAB and fxsA promoters. The ibpAB operon encodes two small heat shock proteins involved in resistance to heat and superoxide stresses [14] and FxsA is an inner membrane protein whose expression is reported to be strongly associated with accumulation of misfolded proteins in the cells [15]. The Pibpfxs tandem promoter is characterised by a low basis level and strong transcriptional activation by the accumulation of aggregation prone proteins in inclusion bodies [11, 16].

Also, a fluorescence-based reporter system for the analysis of ribosome assembly was previously created and extensively characterized [17] and further used to measure the ribosome dynamics in E. coli [18].

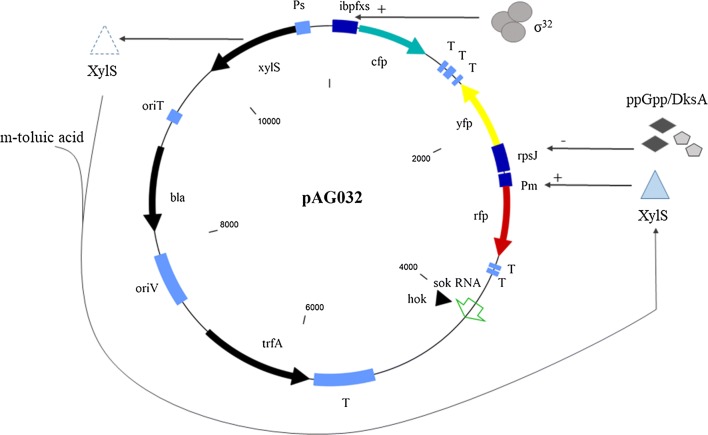

Here, we have taken these previous approaches one step further and constructed a versatile plasmid-based reporter system designated pAG032 (Fig. 1) based on the broad-host range replicon RK2 [19]. The plasmid contains distinct promoters controlling synthesis of three spectrally separable fluorescent proteins mCherry (RFP), mVenus (YFP), and mCerulean (CFP). Cox et al. [20] previously described plasmid pZS2-123 harbouring three inducible promoters expressing these fluorescent proteins and they showed how these reporters can be quantified to independently monitor genetic regulation and noise in single cells of E. coli. In our study, we used the inducible XylS/Pm regulator/promoter system originating from Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid pWW0 to control production of a model protein, RFP. It was proven that this system is suitable for tightly regulated and high-level heterologous protein production in E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria [21]. Next, to monitor for variations in ribosome synthesis in host cells, PrpsJ promoter of the rpsJ ribosomal protein gene was chosen to control yfp expression. In E. coli, PrpsJ coordinates transcription of the S10 operon encoding the 30S subunit of the ribosome. The PrpsJ belongs to r-protein promoters that are strongly inhibited by ppGpp and DksA transcriptional factors in the cells [4, 22]. The transcriptional regulation of rpsJ gene plays a major role when nutrient concentrations are insufficient to sustain the requirements for cell growth due to the enhanced precursor and energy demand required for biomass synthesis [23, 24]. Finally, the cfp reporter gene was placed under control of Pibpfxs to enable monitoring of the heat shock-like responses.

Fig. 1.

Genetic map of the pAG032 reporter plasmid (11,238 nt large) including representation of the control mechanisms of the three promoter/reporter pairs. The XylS/Pm regulator/promoter is inducible by benzoic acid derivatives such as m-toluic acid, while the PrpsJ and Pibpfxs promoters are responsive to intracellular concentrations of ppGpp and σ32, respectively. oriT, origin for conjugative transfer; bla, gene conferring ampicillin resistance; oriV, origin of vegetative replication; trfA; gene encoding an essential initiator protein TrfA; T, transcription terminators; hok/sok RNA, hok-sok suicide elements; Ps, σ70-dependent constitutive promoter; xylS, gene encoding the positive transcriptional regulator XylS

We characterized applicability of the constructed reporter plasmid as a novel tool to analyse host responses relevant for recombinant protein production in E. coli. Moreover, the broad-host range properties of pAG032 were confirmed by performing additional analyses in two other biotechnologically relevant Gammaproteobacteria, Pseudomonas putida and Azotobacter vinelandii.

Results

Design and construction of the broad-host-range reporter plasmid pAG032

As described above, the plasmid system was designed to analyze metabolic responses associated with availability of cellular resources utilized for recombinant protein production. We constructed the system (Fig. 1) by placing a gene encoding RFP under control of the Pm promoter positively regulated by XylS transcriptional factor. XylS/Pm has been widely used for regulated and high-level recombinant protein production in E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria [21], and among all functional elements of the reporter plasmid RFP then serves as an indicator of the target protein production. In addition to inducible XylS/Pm, we used two stress-responsive promoters, PrpsJ and Pibpfxs. The expression of yfp is driven by the PrpsJ, which is significantly upregulated in response to optimal nutrient conditions and deficiencies of ribosomal components. Finally, expression of cfp relies upon the σ32-dependent Pibpfxs promoter [11] responding to heat shock and misfolded proteins. Transcriptional terminators were placed downstream of each reporter gene to avoid problems related to transcriptional read-through [20]. The pAG032 plasmid is based on the broad-host-range RK2 minimal replicon thereby ensuring that the plasmid is applicable in many different Gram-negative bacterial species [19]. The minimal RK2 replicon consists of the origin of vegetative replication (oriV) and its cognate trfA gene encoding TrfA replication initiator protein [19, 25]. The copy number of the plasmid is 5–7 per genome, and this number can easily be changed to different numbers up to above 100 copies per genome by replacing trfA with available mutant versions of trfA gene [26]. The latter option could be valuable to monitor metabolic burden and other responses associated with increased recombinant protein production and increased plasmid copy numbers. The pAG032 further contains oriT enabling conjugative transfer and the hok-sok suicide elements previously demonstrated to ensure segregational stability of RK2-based plasmid also under high-cell density cultivations [27].

Construction of pAG032 was done based on the expression plasmid pVB-1E0B1 IL-1RA (Table 1) in a step-wise process involving creation of versions containing one (pAG002, pAG014, and pAG017) and two (pAG019, pAG024 and pAG028) reporter genes used in the final reporter plasmid pAG032. In all cases, the functionality of the plasmid intermediates was tested for production of the relevant active reporter proteins in E. coli (data not shown). Next, we tested the functionality of pAG032 by individually monitoring expression level of the three reporter proteins in recombinant E. coli BW25113 (pAG032) cells cultivated under different conditions causing various stress responses as relevant for the particular promoter/reporter pair being investigated.

Table 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Name | Key features | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pZS2-123 | cfp under control of PLtetO-1, yfp under control of PLlacO-1, rfp under control of Plac/ara-1, Kanr | [20] |

| pibpfxsT7lucA | ibpfxs::lucA reporter unit, Ampr | [11] |

| pJB658 | RK2 replicon, trfA gene, XylS/Pm regulator/promoter system, Ampr | [25] |

| pVB-1E0B1 IL-1RA | RK2 replicon, trfA gene with cop-271 mutation, XylS/Pm regulator/promoter system, hok-sok suicide system, Ampr | Vectron Biosolutions |

| pAG001 | RK2 replicon, trfA gene, hok-sok suicide system, Ampr | This study |

| pAG002 | pAG001 plasmid with rfp under control of XylS/Pm, Ampr | This study |

| pAG014 | pAG001 plasmid with cfp under control of ibpfxs, Ampr | This study |

| pAG017 | pAG001 plasmid with yfp under control of rpsJ, Ampr | This study |

| pAG019 | pAG001 plasmid with rfp under control of XylS/Pm and yfp under control of rpsJ, Ampr | This study |

| pAG024 | pAG001 plasmid with rfp under control of XylS/Pm and cfp under control of ibpfxs, Ampr | This study |

| pAG028 | pAG001 plasmid with cfp under control of ibpfxs and yfp under control of rpsJ, Ampr | This study |

| pAG032 | pAG001 plasmid with rfp under control of XylS/Pm, cfp under control of ibpfxs and yfp under control of rpsJ, Ampr | This study |

Changes of yfp expression controlled by PrpsJ promoter in E. coli cells exposed to sub-lethal concentrations of translation-inhibiting antibiotic chloramphenicol

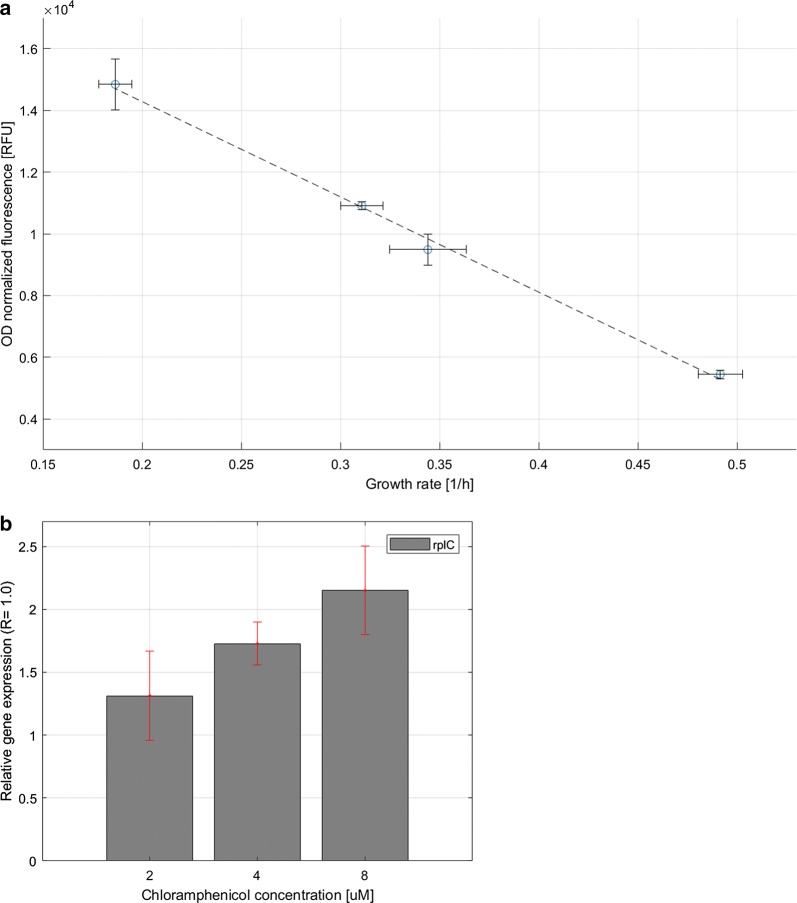

The translational capacity is one of limiting factors for recombinant protein production rate [1] and bacterial growth rate [28]. Chloramphenicol is a translation-inhibiting antibiotic and it has previously been demonstrated that exposure of E. coli cells to sub-lethal chloramphenicol concentrations is accompanied by transcriptional upregulation of rRNA and ribosomal protein genes as a response to slow translation and accumulation of amino acid precursors. The result is an elevated intracellular RNA/protein ratio [29]. To test the responsiveness of the PrpsJ promoter to such conditions, recombinant E. coli cells were cultivated using different sub-lethal concentrations of chloramphenicol and assayed for YFP fluorescence intensity. The results showed that increased concentrations of chloramphenicol in the growth medium led to the expected reduced growth rate of the cells, and also, to the increased YFP fluorescence levels in comparison to control cells, indicating transcriptional upregulation of PrpsJ (Fig. 2a). The elevated YFP fluorescence level was inversely proportional to the growth rate of the cells, and supplementation of growth media with antibiotic concentrations of 2, 4 and 8 μM resulted in 1.7-, 2.0- and 2.7-fold increased YFP activity, respectively, in comparison to the cells cultivated in the absence of chloramphenicol.

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional upregulation of PrpsJ in response to cell growth in various sub-lethal doses of chloramphenicol, measured as a correlation of PrpsJ-dependent expression of YFP activity and growth rate (a) or rplC transcript accumulation (b). The growth rates were calculated based on change in OD600nm values measured every 1 h over a period of 3 h after adding chloramphenicol. OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated from measurements taken 3 h after adding chloramphenicol. RNA samples collection was performed after 15-min incubation of the recombinant cells in the presence of chloramphenicol. Relative gene expression (ΔΔCt) is presented as the level of rplC transcript in samples treated with chloramphenicol (2, 4, 8 μM) relative to its abundance in reference samples (0 μM). The data presented are from three independent biological replica (average ± SD)

In order to confirm that chloramphenicol treatment affects transcriptional upregulation of ribosomal protein genes, we measured transcription levels of the chromosomal rplC gene, which is part of the rpsJ (S10) operon in E. coli and encodes the 50S ribosomal subunit protein L3. The rplC transcript level was measured by quantitative PCR in RNA samples extracted from untreated E. coli cells and cells cultivated for 15 min after addition of increasing doses (2, 4 and 8 μM) of chloramphenicol [30]. The results showed that rplC transcript levels increased with increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol (Fig. 2b), in agreement with the YFP activity results (Fig. 2a).

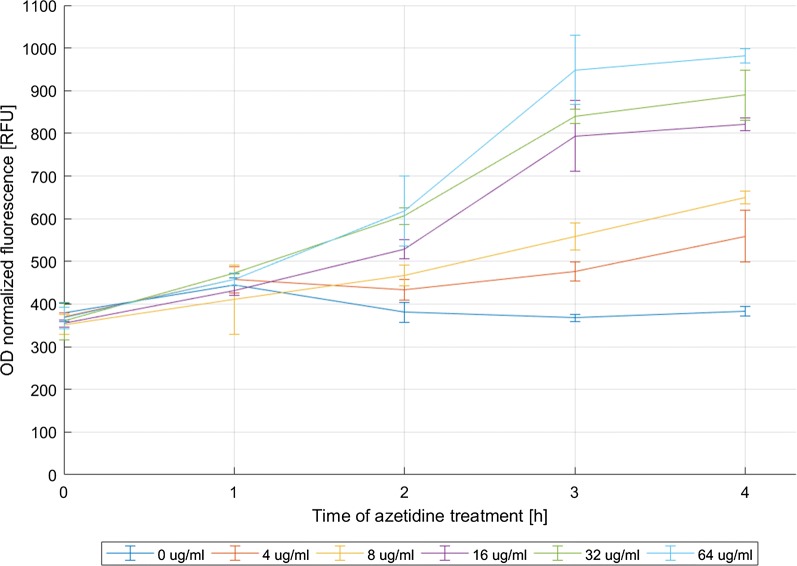

Elevated expression of cfp from Pibpfxs in cells exposed to azetidine is likely caused by protein misfolding and aggregation

Recombinant overexpression sometimes results in protein misfolding and aggregation. Previously, it has been shown [31–33] that incorporation of amino acid analogues during protein synthesis leads to formation of proteins with abnormal conformation and, prior to proteolytic degradation, such proteins form insoluble aggregates. This causes transcriptional upregulation of various heat shock chaperones regulated by the sigma factor σ32. In the plasmid pAG032, the σ32 dependent Pibpfxs tandem promoter controls cfp expression. To test if this promoter/reporter pair can be used to monitor cellular response to protein misfolding and aggregation, we cultivated recombinant E. coli cells in the presence of increasing concentrations (0, 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 μg/ml) of a proline analogue—azetidine. Samples were collected at various time points after azetidine addition (1, 2, 3 and 4 h) and analysed for CFP fluorescence, and the results are presented in Fig. 3. As anticipated, CFP fluorescence intensity increased with increasing time and dose of azetidine. The incubation with 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 μg/ml azetidine for 4 h resulted in 1.5-, 1.7-, 2.1-, 2.3- and 2.6-fold increase in CFP fluorescence, respectively, compared to the untreated cells.

Fig. 3.

Time-course-activity measurements of YFP expressed from Pibpfxs in E. coli BW25113 (pAG032) cultivated in the presence of different concentrations (0, 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 μg/ml) of azetidine. Incorporation of azetidine during protein synthesis promotes formation of abnormal proteins that tend to misfold and aggregate. The OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated based on the measurements taken every 1 h up to 4 h after addition of azetidine. The data presented are from three independent biological replicas (average ± SD)

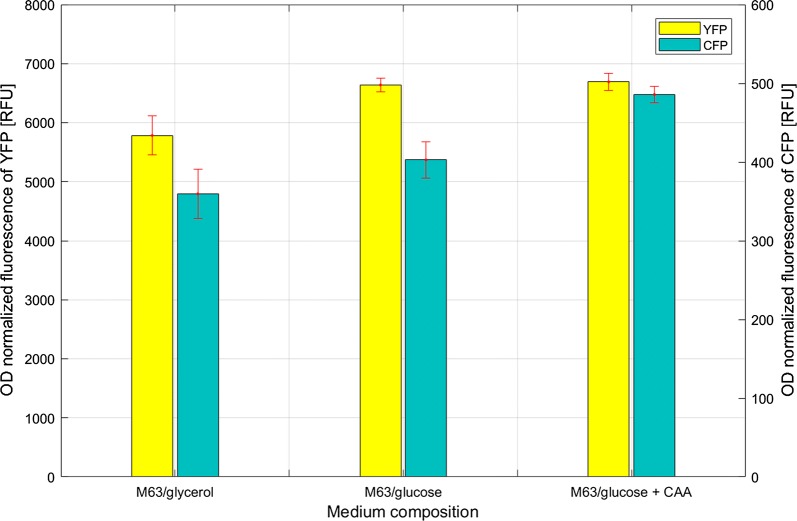

Simultaneous fluorescence measurement of reporter proteins YFP and CFP in cells cultivated in different growth media indicates host effects related to ribosome synthesis rates and σ32-mediated responses

The important property of RFP, CFP and YFP as reporter proteins is that they have been reported to exhibit distinct fluorescence signals [15] allowing simultaneous and independent monitoring of each reporter protein fluorescence with regard to the studied parameters. We took advantage of that and studied YFP and CFP fluorescence in recombinant cells cultivated in three different growth conditions; M63 minimal medium supplemented with glycerol (M63/glycerol), glucose (M63/glucose), or glucose with casamino acids (M63/glucose + CAA). These growth media were chosen to promote different growth rates that should affect expression level of YFP from the PrpsJ promoter. As presented in Fig. 4, the fluorescence of the two reporter proteins was individually measured and quantified. The results show that the fluorescence of both proteins increased slightly (up to 1.2-fold) as a consequence of use of media stimulating higher cell growth rates. The increase was approximately proportional to that of the growth rate (Additional file 1: Table S1). The YFP data are in agreement with previous reports indicating that fast growing bacteria are expected to have higher demand for ribosomal proteins [28]. In addition, it was previously suggested that fast growth promotes increased rates of cellular protein synthesis, which may become a burden to the folding machinery [34, 35], and in that case increased cfp expression from Pibpfxs would be expected which is in accordance with results shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Recombinant cells were cultivated in minimal medium supplemented with glycerol (M63/glycerol), glucose (M63/glucose) and glucose + casamino acids (M63/glucose + CAA), to ensure different growth rates (Additional file 1: Table S1). The OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated based on measurements taken 3 h after a time point when all the cultures displayed approximate OD600nm (~ 0.35). The data presented are from three independent biological replicas (average ± SD)

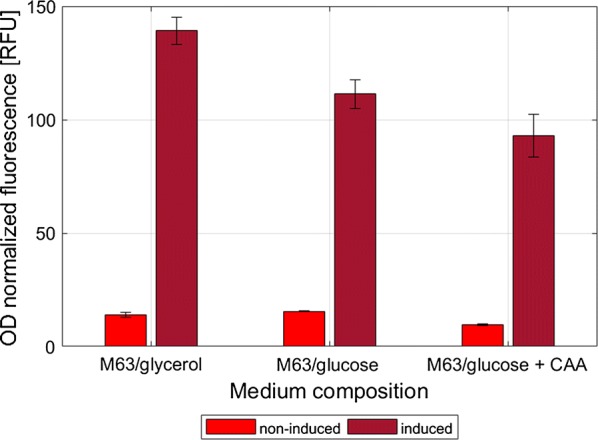

Inducible expression of rfp from XylS/Pm varies under different growth conditions

The XylS/Pm expression cassette has been widely used for high-level recombinant protein production in E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria, and its tight regulation has been demonstrated to be favorable when expressing cell-toxic heterologous proteins under high-cell density conditions [27, 36]. In this study, the reporter gene rfp was put under control of the XylS/Pm in order to characterize this expression system in the context of plasmid pAG032. Recombinant cells were cultivated in three different growth media M63/glycerol, M63/glucose, and M63/glucose + CAA, as described above. Expression of rfp was induced by addition of m-toluic acid (1 mM), and the results are shown in Fig. 5. The rfp expression was highly inducible and levels of RFP fluorescence of induced cultures decreased with increasing cell growth rates of the cells. The highest RFP fluorescence was observed in cells growing on M63/glycerol, which was 1.5-fold higher than in case of the fastest-growing cells cultivated on M63/glucose + CAA. Still, it should be noted that the growth rate after induction with m-toluate was most strongly inhibited for the cells growing in M63/glucose + CAA (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 5.

Responsiveness of the XylS/Pm reporter unit during cultivation of E. coli BW25113 in M63 medium supplemented with either glycerol (M63/glycerol), glucose (M63/glucose) or glucose and casamino acids (M63/glucose + CAA). The OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated from measurements taken at the time point corresponding to 3 h after the induction. The OD600nm of the samples at the point of induction was similar for all cultures despite differences in the growth rate. The data presented are from three independent biological replica (average ± SD)

Plasmid pAG032 functions in other Gammaproteobacteria, Pseudomonas putida and Azotobacter vinelandii, indicating its potential as a broad-host-range tool

The broad-host range properties of the XylS/Pm system have been well documented, and importantly the inducer, m-toluate, enters cells via passive diffusion and most bacteria cannot metabolize it [21]. The PrpsJ and Pibpfxs promoters of pAG032 as well as the reporter genes used are not well studied in species other than E. coli. Therefore pAG032 was transformed to Pseudomonas putida KT2440 (TOL plasmid cured strain) and to Azotobacter vinelandii OP (UW) to explore its broad-host range potential. These two organisms were selected as relevant model hosts due their biotechnological applications for production of recombinant proteins and biopolymers [37, 38].

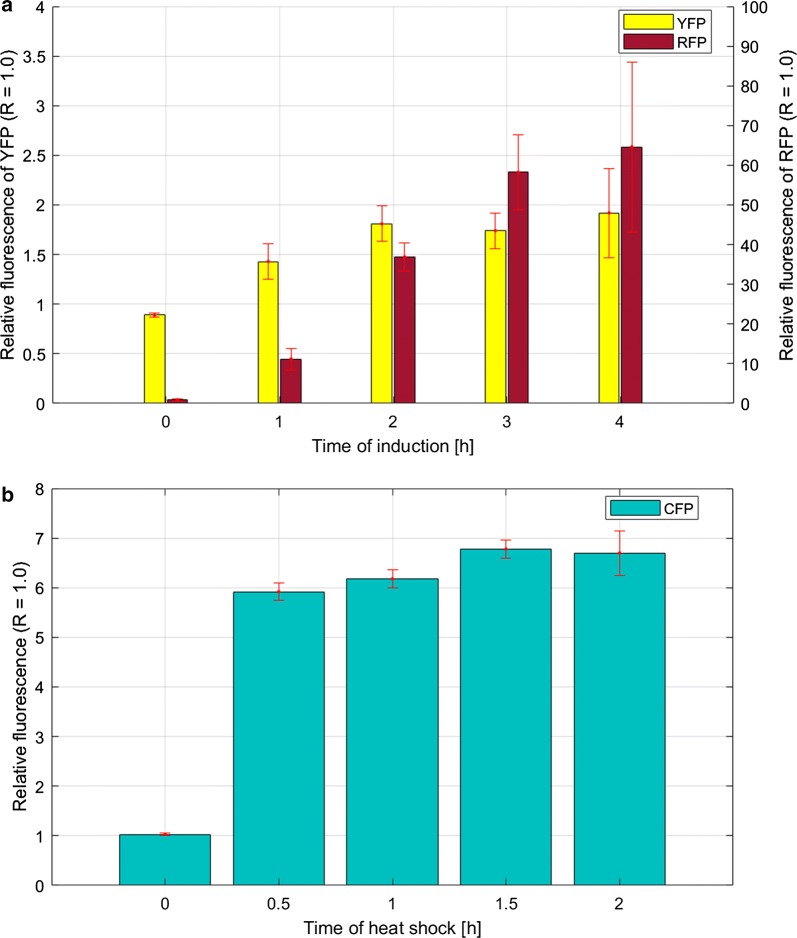

First, we analysed expression of all three reporter proteins in recombinant P. putida cells in the presence and absence of m-toluic acid (1 mM) under standard growth conditions (see “Methods” section), and the results are presented in Fig. 6a. As expected, rfp expression from the XylS/Pm was tightly regulated, and the induction ratio was found to be 64-fold 4 h after the induction. Interestingly, the expression level of yfp from ribosomal promoter PrpsJ was 1.9-fold upregulated upon 4-h incubation in the presence of m-toluic acid. Cfp expression from Pibpfxs remained constant irrespective of the presence of m-toluic acid (data not shown). To test for specific responsiveness of the latter promoter in P. putida, we performed an additional experiment where the cell cultures were shifted from 30 °C to 42 °C to induce a heat shock response. It was previously suggested that P. putida employs principally the same system as that in E. coli to control the activity and quantity of σ32 in response to heat stress and protein misfolding and aggregation [39]. The results of our experiment (Fig. 6b) showed that cfp expression from Pibpfxs increased 5.9-fold already 30 min after the temperature shift, in comparison to the control cells cultivated at 30 °C.

Fig. 6.

Responsiveness of the PrpsJ and XylS/Pm reporter units during cultivation of P. putida KT2440 under induced conditions (a) and the course of the Pibpfxs activity during cultivation at 42 °C (b). Data represent relative fluorescence levels shown as a ratio of OD600nm normalized fluorescence values at different time points under conditions of induction or heat shock to the OD600nm normalized fluorescence intensity of the reference cultures (R) growing in the absence of the inducer at 30 °C. The OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated based on measurements taken every 1 h up to 4 h after the induction and every 0.5 h up to 2 h after the temperature shift. The data presented are from three independent biological replica (average ± SD)

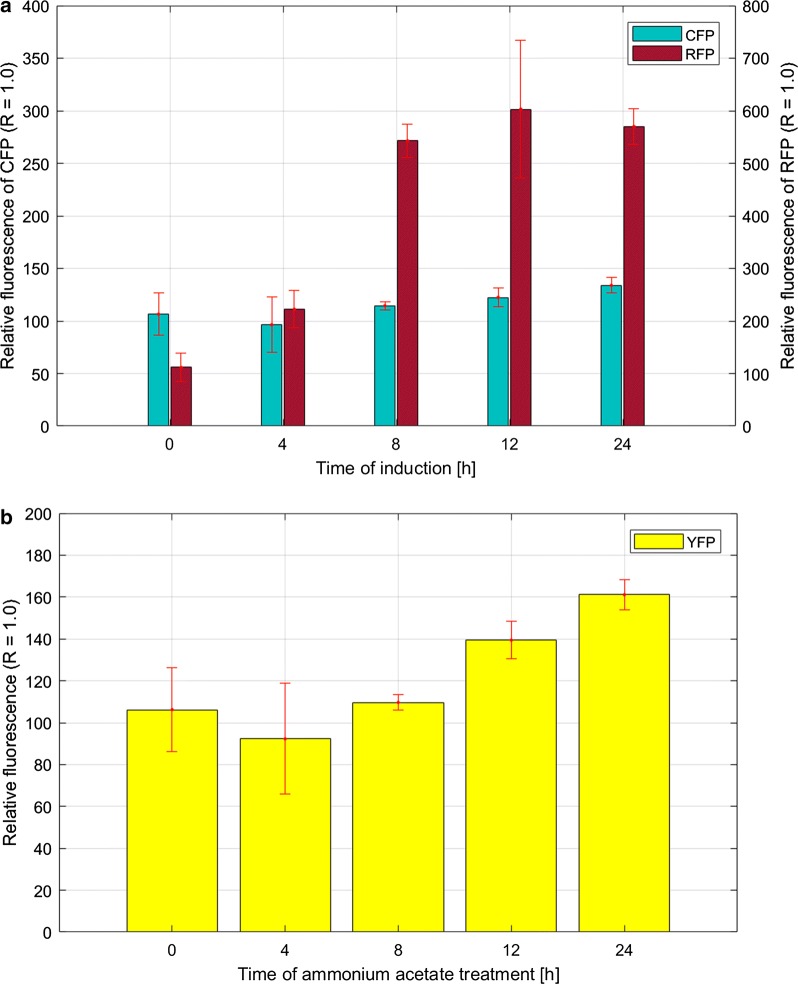

Next, we performed analogous studies by cultivating the recombinant A. vinelandii cells with and without m-toluic acid (0.5 mM), and the results showed that rfp expression from the XylS/Pm increased up to 6-fold after 12-h growth in the presence of the inducer (Fig. 7a). The induction window of the XylS/Pm for this host was lower than in case of E. coli and P. putida (see above). We noticed that the cfp expression level from the σ32-dependent Pibpfxs promoter increased slightly; up to 1.34-fold after 24 h growth in the presence of m-toluic acid compared to reference cells. The expression level of yfp from the PrpsJ promoter did not change significantly upon addiction with m-toluate (data not shown). As A. vinelandii is a nitrogen-fixing bacterium, it is therefore routinely cultivated in media lacking any nitrogen source. Nitrogen fixation is energy-demanding process, and both the nitrogen fixation and the partially uncoupled respiration protecting the nitrogenase against oxygen result in large demand for carbon that cannot be utilized for growth [37]. Therefore, we decided to test if supplementation with 10 mM ammonium acetate used as the nitrogen source, affects growth rate and expression of yfp from the PrpsJ promoter similarly to the effect observed for E. coli cultivated in richer media (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 7b, up to 1.6-fold increased YFP fluorescence was observed after 24 h of incubation in the presence of ammonium acetate in comparison to control cultures.

Fig. 7.

Responsiveness of the Pibpfxs and XylS/Pm reporter units during cultivation of A. vinelandii OP (UW) under induced conditions (a) and the activity of PrpsJ ribosomal promoter after the addition of ammonium acetate (b). Data represent relative fluorescence levels expressed as a ratio of OD600nm normalized fluorescence values at different time points under conditions of induction or ammonium acetate supplementation to the OD600nm normalized fluorescence intensity of the reference cultures (R) growing in the absence of the inducer or ammonium acetate. The OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated based on measurements taken up to 24 h after the induction or ammonium acetate supplementation. The data presented are from technical triplicates (average ± SD)

Discussion

The advent of efficient and precise genome engineering tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 significantly accelerated the traditional endonuclease- and recombineering-based strain development processes useful for metabolic engineering [40, 41]. According to Mahalik et al. [1] engineering of bacterial hosts for improved capability for recombinant protein production requires removing translational bottlenecks and redirecting the metabolic flux away from biomass formation towards target protein synthesis. Moreover, the engineered cells should be characterized for their ability to efficiently fold and export proteins in order to prevent aggregation of the newly synthesized proteins inside the cytoplasm. In this work, we created the reporter system pAG032 that allows monitoring of translational capacity of bacterial cells and stresses related to protein misfolding. Our results confirmed that the activity of the PrpsJ ribosomal promoter of pAG032 corresponded to transcriptional upregulation of the chromosomal ribosome synthesis gene rplC in E. coli. Furthermore, by combining the PrpsJ ribosomal promoter reporter with the well-characterized σ32-dependent Pibpfxs on pAG032, we enabled monitoring of heat shock-like stress responses that may result from genome engineering aiming solely for improved translational capacity. The responsiveness of the Pibpfxs promoter controlling expression of cfp reporter gene was confirmed in our study by analysis of CFP fluorescence in cell cultures cultivated in a presence of the proline analogue azetidine. The activity of these two stress-responsive reporter units was further quantified by using different growth conditions of the recombinant E. coli cells. As PrpsJ-dependent YFP fluorescence intensity was monitored during the exponential growth phase with nutrient concentrations sufficient for steady growth rate [10, 18], the activity of this ribosomal reporter unit increased in correspondence to the increased growth rate. These results are in agreement with previously reported data indicating a positive correlation of ribosomal protein synthesis with growth rate in E. coli [42]. Our results using A. vinelandii as an alternative host also showed the expected growth-related expression of YFP from PrpsJ. Moreover, it has previously been proposed that high bacterial growth rate promotes increased rates of cellular protein synthesis, which may become a burden to the protein folding machinery [34, 35]. This may explain why the expression of cfp from σ32-dependent Pibpfxs promoter also increased in response to elevated growth rate of the E. coli cells.

The third reporter unit of pAG032 is the inducible XylS/Pm system controlling expression of RFP, and we chose its non-mutated version previously shown to display very low background expression to ensure tightly regulated and high-level induced expression of, in principle, any target protein using pAG032 [43]. Contrary to YFP and CFP, expression level of RFP from the XylS/Pm promoter decreased with the increasing growth rate. According to a model proposed by Klumpp et al. [44], the concentrations of constitutively expressed regulators is reduced with increased cell growth rate, mainly because of the increase of cell volume. It was plausible to assume that such effects can explain our results with RFP.

We constructed the reporter system to monitor product formation under different growth conditions by using the XylS/Pm promoter system, and we demonstrated that this expression cassette can be used in combination with the two other stress-responsive reporter units. As we see it, expression of the individual reporter genes used in this study is likely not independent. For example, a dependence is indicated by the fact the σ32-mediated heat shock response may induce production of ppGpp [45, 46] leading to the PrpsJ inhibition or by influence of inducer on upregulation of stress-responsive promoters (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Still, even under the assumption that recombinant expression of YFP and CFP may impose some stress to the host cells, in addition to the stress caused by inducible expression from XylS/Pm, the reporter system can discriminate between the effects dependent on different strain background during comparative studies. Such analysis of variation in expression of three interdependent reporter units in a subset of different genetic variants of E. coli has been previously demonstrated by Cardinale et al. [47].

One important aim was to design and construct pAG032 with promoters and a replicon suitable for broad-host range applications, and we were able to demonstrate its usefulness and detect activity and functionality of all promoters and concomitant reporter proteins in P. putida and A. vinelandii both representing the Gammaproteobacteria subgroup. The detected expression levels of the reporter proteins in A. vinelandii were low compared to those obtained in E. coli and P. putida, possibly due to non-optimal codons of reporter genes in this host. Moreover, plasmid derivative pAG028, containing the two promoter/reporter cassettes PrpsJ/yfp and Pibpfxs/cfp, can also possibly prove to be useful for analysing host effects in combination with overproduction of any target protein of interest expressed from a separate compatible expression vector and in any Gram-negative species.

Conclusions

In this study, we created a novel reporter system suitable for monitoring of native stress responses and translational capacity in E. coli as well as in other Gram-negative bacteria. The system is based on individual expression of three different fluorescent proteins from three different promoters, which makes it useful for high-throughput screening accompanying effective strain development studies and for on-line monitoring of host parameters during cultivation. Characterization of cells in terms of the stringent and heat shock-like stress responses should allow for selection of strains displaying improved translational capacity and ability to synthesise correctly folded proteins.

Methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

Escherichia coli K-12 BW25113 [48] served as an expression host for studying the responsiveness of the reporter system. E. coli DH5α was used for cloning purposes. P. putida KT2440 (TOL plasmid cured derivative [49]) and A. vinelandii OP (UW) [37] were utilized as alternative host organisms. E. coli and P. putida were routinely grown at 37 °C or 30 °C, respectively, with 225 rpm shaking in liquid LB medium or on solid LB plates, unless stated otherwise. The M63 medium used in this study was composed as described by others [50] and supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) glycerol or 0.2% (w/v) glucose and/or 0.1% (w/v) Casamino acids. A. vinelandii was routinely grown in liquid Burk’s medium (pH 7.2) at 30 °C, 225 rpm shaking [51]. For plasmid selection in E. coli, P. putida and A. vinelandii, ampicillin was used at concentrations 100 μg/ml, 500 μg/ml and 25 μg/ml, respectively.

Plasmids construction

Plasmids used as templates or constructs that were generated in this study are listed in Table 1. DNA sequences of the PCR primers used during cloning steps described below are presented in Table 2. Plasmid pAG001 was used as a starting point for the construction of various intermediate versions of the reporter system. For the construction of pAG001, pJB658 and pVB-1E0B1 IL-1RA were digested with EcoRI and ApaLI. The fragment corresponding to the pVB-1E0B1 IL-1RA backbone and the trfA gene of pJB658 were ligated. The resulting pAG001 was further digested with NdeI and NotI. In order to construct pAG002, the rfp region together with T7TE+ terminator was amplified from pZS2-123 using RfpF_NdeI and RfpR_NotI and the PCR-fragment was digested with NdeI and NotI prior to insertion into pAG001. Plasmid pAG014 was created by Gibson assembly [52] of three fragments: NotI/MfeI-digested pAG001 backbone, the region comprising cfp gene and RNAI terminator amplified from pZS2-123 using 014_cfp_F and 014_cfp_RBS2_R and the region corresponding to ibpfxs with modified 5′-UTR amplified from pibpfxsT7lucA by using 014_pib_F and 014_pib_RBS2_R. The most optimal 5′-UTR sequence for cfp gene was chosen based on analysis of translation initiation rate predicted by RBS calculator [53]. In the case of yfp and rfp, the moderate strength SD8 RBSs and the stronger RBS from gene 10 of phage T7 were used, respectively, as proposed by Cox et al. [20]. Construction of pAG017 involved amplification of the yfp gene sequence together with TR2-17 and TL17 terminators from pZS2-123 by using YfpF_NdeI and YfpR_NotI. After digestion with NdeI and NotI of both the amplified pZS2-123 cfp and pAG001, the two fragments were ligated and the resulting vector was digested with MfeI and NdeI. The obtained backbone was ligated with the sequence of rpsJ promoter [54] synthesized as gBlock Gene Fragment (IDT) and digested with MfeI and NdeI prior to ligation. Construction of plasmid pAG032 was based on Gibson assembly of three fragments: the pAG002 backbone amplified using primers 032_002_F and 032_002_R, the ibpfxs::cfp region with RNAI terminator amplified from pAG014 using 032_014_F and 032_014_R and the rpsJ::yfp region with TR2-17 and TL17 terminators amplified from pAG017 using 032_017_F and 032_017_R. Additionally, two-gene versions of the reporter system were created. All these plasmids are available upon request. The rpsJ::yfp region with TR2-17 and TL17 terminators was amplified from pAG017 with primers rpsJ_yfpF_SnaBI and rpsJ_yfpR_NheI and cloned into pAG002 via SnaBI and NheI, generating pAG019. Similarly, SnaBI and NheI were used to clone the ibpfxs::cfp region with RNAI terminator amplified from pAG014 using pibfxs_cfpF_SnaBI and pibfxs_cfpR_NheI into pAG002. The ligation product was pAG024. Construction of plasmid pAG028 was based on Gibson assembly of two fragments: pAG017 backbone amplified with 021_rpsJ_F and 021_rpsJ_R and ibpfxs::cfp region with RNAI terminator amplified from pAG014 using 021_ibpfxs_F and 021_ibpfxs_R.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| a) PCR primers: | |

| RfpF_NdeI | ATATTCATATGGTTTCCAAGGGCGAGGAGG |

| RfpR_NotI | TTTATAGCGGCCGCAAAAACAGCCGTTGCCAGAAAG |

| 014_cfp_F | ACCCTCCCTCGGCTTGTGCCGCGGCCGCAAAAGGAAAAGA |

| 014_cfp_RBS2_R | GGAATATAGCAAATAAGGAGGAGGAAAATGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGCTG |

| 014_pib_F | AGCTTTTGTTCGGATCCAGCAAACTGCAAAAAAAAGTCCGCTGA |

| 014_pib_RBS2_R | TTTCCTCCTCCTTATTTGCTATATTCCACCTGAATGGGTTGCGAATCGCGTTTAG |

| YfpF_NdeI | CGTGCATATGAGCAAAGGTGAAGAAC |

| YfpR_NotI | TGCTAGCGGCCGCAGGACAGCTATTGTAGATAAG |

| 032_002_F | CCCGGTTTGATAGGGATAAG |

| 032_002_R | TACGGATGAGCATTCATCAG |

| 032_014_F | CTGATGAATGCTCATCCGTAGATCCAGCAAACTGCAAAAAAAAG |

| 032_014_R | CAATAGCTGTCCTGCGGCCGATCGAGTTGCTGGAGATTGTG |

| 032_017_F | CGGCCGCAGGACAGCTATTGTA |

| 032_017_R | CTTATCCCTATCAAACCGGGATACCCTCCCTCGGCTTGTG |

| rpsJ_yfpF_SnaBI | GAATGCTCATCCGTAATTACCGCGAAACGGATACCCTCCCTC |

| rpsJ_yfpR_NheI | CTTATCCCTATCAAACCGGGGGCCTTTAGGTCTTCTTCTG |

| pibfxs_cfpF_SnaBI | CTTATCCCTATCAAACCGGGATCGAGTTGCTGGAGATTGT |

| pibfxs_cfpR_NheI | GAATGCTCATCCGTAATTACGGCCTTTAGGTCTTCTTCTG |

| 021_rpsJ_F | AGCTTGACCTGTGAAGTGAA |

| 021_rpsJ_R | CTGAGATCAGCTTTTGTTCG |

| 021_ibpfxs_F | CGAACAAAAGCTGATCTCAGAGGCCTTTAGGTCTTCTTCT |

| 021_ibpfxs_R | TTCACTTCACAGGTCAAGCTAAGGAAAAGATCCGGCAAAC |

| b) qPCR primers: | |

| cysG_F1 | GTATTCCACTCACGCATCGC |

| cysG_R1 | CGCCACCGGTTTTTAAGTGT |

| rplC_F2 | TGACCGATAGAACCCGGAAC |

| rplC_R2 | CTGGAACTTCCGTACCCAGG |

Expression studies and activity measurement of the reporters

Recombinant E. coli, P. putida and A. vinelandii strains were grown over-night in 2-10 ml of adequate liquid medium with ampicillin. Afterwards, 20 ml of the fresh medium with the antibiotic were inoculated with the overnight culture to an initial OD of 0.05 measured at 600 nm for E. coli and P. putida and at 660 nm for A. vinelandii. Following incubation in shake flasks, the XylS/Pm-mediated protein expression was induced in exponential phase (OD = 0.4–0.6) by adding m-toluic acid to a final concentration of 1 mM for E. coli and P. putida and 0.5 mM for A. vinelandii. Heat shock was applied by transferring the cultures of P. putida from 30 °C to 42 °C, 225 rpm shaking, at OD600 = 0.3–0.4. In order to reduce intracellular levels of ppGpp, 10 mM ammonium acetate was added to the cultures of A. vinelandii at OD660 = 0.3–0.4.

Fluorescence measurements were performed with the Tecan Infinite M200 (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) plate reader. Fluorescence intensity was determined directly from the cultures (M63, Burk’s medium) or after resuspension in PBS (LB medium) in order to reduce background signal. The following fluorescent filter setup was used for the detection: [1] CFP excitation: 433 nm; emission: 475 nm; [2] YFP excitation: 505 nm; emission: 538 nm; [3] RFP excitation: 580 nm; emission: 615 nm. The gain was set to 100 for RFP and 80 for CFP and YFP.

Transcript analysis by qPCR

Following adequate incubation in shake flasks, 3 ml of cell cultures were stabilized with RNAlater stabilization solution (Qiagen). The subsequent total RNA isolation was achieve using RNAqueous® Total RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). RNA samples were treated with TURBO™ DNase (Ambion) and used for cDNA synthesis with First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Two-step qPCR with the power PowerSYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used for quantification of cysG and rplC transcripts. All steps were performed as described by the manufacturers. PCR cycles were 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 15 s; 62 °C for 1 min) and one additional stage of amplification to generate a melt curve. Results were analyzed with QuantStudio™ Design & Analysis Software (Applied Biosystems) and data were normalized as described previously [55]. Primer pairs used during amplification are listed in Table 2. Efficiency was verified for each pair of the primers (Table S2). Transcript generated from the cysG gene was used for normalization [56].

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1. Growth rates (h−1) of E. coli BW25113 cells carrying pAG032. Table S2. Efficiencies of qPCR reaction (%) and R2 coefficients of determination of the standard curves for primer pairs used for amplification. Figure S1. Iinfluence of m-toluic acid (1 mM) on activity of (A) the XylS/Pm (only pAG032), (B) PrspJ and (C) Pibpfxs reporter units during cultivation of E. coli BW25113 transformed with three-gene version of the plasmid (pAG032) and two-gene version of the plasmid (pAG028). Cell were grown in M63 medium supplemented with glucose. The OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated from measurements taken at the time point corresponding to 3 h after the induction. The data presented are from three independent biological replica (average ± SD). Please note that values of OD normalized fluorescence, not relative fluorescence, are given.

Authors’ contributions

Most experimental work was done by AG, with input from KB and SH. HE, MI and PN has been involved in planning and discussions throughout, and the work has been leaded by TB together with AG. All authors contributed actively to writing of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Rahmi Lale for helpful discussions and advice.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the ERASysAPP project LeanProt financed by Research Council of Norway (257147), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and Estonian Research Council.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Agnieszka Gawin, Email: agnieszka.gawin@ntnu.no.

Karl Peebo, Email: karl@tftak.eu.

Sebastian Hans, Email: sebastian.hans@tu-berlin.de.

Helga Ertesvåg, Email: helga.ertesvag@ntnu.no.

Marta Irla, Email: marta.k.irla@ntnu.no.

Peter Neubauer, Email: peter.neubauer@tu-berlin.de.

Trygve Brautaset, Phone: +47 98 28 39 77, Email: trygve.brautaset@ntnu.no.

References

- 1.Mahalik S, Sharma AK, Mukherjee KJ. Genome engineering for improved recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:177. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers JK, Taylor ND, Church GM. Biosensor-based engineering of biosynthetic pathways. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;42:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou CP. Engineering cell physiology to enhance recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76(3):521–532. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemke JJ, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Burgos HL, Hedberg G, Ross W, Gourse RL. Direct regulation of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein promoters by the transcription factors ppGpp and DksA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(14):5712–5717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019383108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K, Bittner AN, Wang JD. Diversity in (p)ppGpp metabolism and effectors. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;24:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaca AO, Kajfasz JK, Miller JH, Liu K, Wang JD, Abranches J, et al. Basal levels of (p)ppGpp in Enterococcus faecalis: the magic beyond the stringent response. MBio. 2013;4(5):e00646–e00713. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00646-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross W, Vrentas CE, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Gaal T, Gourse RL. The magic spot: a ppGpp binding site on E. coli RNA polymerase responsible for regulation of transcription initiation. Mol Cell. 2013;50(3):420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann F, Rinas U. Roles of heat-shock chaperones in the production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2004;89:143–161. doi: 10.1007/b93996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neubauer P, Fahnert B, Lilie H, Villaverde A. Protein inclusion bodies in recombinant bacteria. In: Shively JM, editor. Inclusions in prokaryotes. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2006. pp. 237–292. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraft M, Knupfer U, Wenderoth R, Pietschmann P, Hock B, Horn U. An online monitoring system based on a synthetic sigma32-dependent tandem promoter for visualization of insoluble proteins in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75(2):397–406. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakahigashi K, Yanagi H, Yura T. Isolation and sequence analysis of rpoH genes encoding sigma 32 homologs from Gram negative bacteria: conserved mRNA and protein segments for heat shock regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(21):4383–4390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakahigashi K, Yanagi H, Yura T. Regulatory conservation and divergence of sigma32 homologs from Gram-negative bacteria: serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(9):2402–2408. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2402-2408.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitagawa M, Matsumura Y, Tsuchido T. Small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, are involved in resistances to heat and superoxide stresses in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;184(2):165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesley SA, Graziano J, Cho CY, Knuth MW, Klock HE. Gene expression response to misfolded protein as a screen for soluble recombinant protein. Protein Eng. 2002;15(2):153–160. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siurkus J, Panula-Perala J, Horn U, Kraft M, Rimseliene R, Neubauer P. Novel approach of high cell density recombinant bioprocess development: optimisation and scale-up from microliter to pilot scales while maintaining the fed-batch cultivation mode of E. coli cultures. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikolay R, Schloemer R, Schmidt S, Mueller S, Heubach A, Deuerling E. Validation of a fluorescence-based screening concept to identify ribosome assembly defects in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(12):e100. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Failmezger J, Ludwig J, Niess A, Siemann-Herzberg M. Quantifying ribosome dynamics in Escherichia coli using fluorescence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2017;364(6):fnx55. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blatny JM, Brautaset T, Winther-Larsen HC, Haugan K, Valla S. Construction and use of a versatile set of broad-host-range cloning and expression vectors based on the RK2 replicon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63(2):370–379. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.370-379.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox RS, 3rd, Dunlop MJ, Elowitz MB. A synthetic three-color scaffold for monitoring genetic regulation and noise. J Biol Eng. 2010;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gawin A, Valla S, Brautaset T. The XylS/Pm regulator/promoter system and its use in fundamental studies of bacterial gene expression, recombinant protein production and metabolic engineering. Microb Biotechnol. 2017;10(4):702–718. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgos HL, O'Connor K, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Gourse RL. Roles of transcriptional and translational control mechanisms in regulation of ribosomal protein synthesisin Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2017;199(21):e00407-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00407-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navarro Llorens JM, Tormo A, Martinez-Garcia E. Stationary phase in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34(4):476–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singha TK, Gulati P, Mohanty A, Khasa YP, Kapoor RK, Kumar S. Efficient genetic approaches for improvement of plasmid based expression of recombinant protein in Escherichia coli: a review. Process Biochem. 2017;55:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blatny JM, Brautaset T, Winther-Larsen HC, Karunakaran P, Valla S. Improved broad-host-range RK2 vectors useful for high and low regulated gene expression levels in Gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid. 1997;38(1):35–51. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figurski DH, Meyer RJ, Helinski DR. Suppression of Co1E1 replication properties by the Inc P-1 plasmid RK2 in hybrid plasmids constructed in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1979;133(3):295–318. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sletta H, Nedal A, Aune TE, Hellebust H, Hakvag S, Aune R, et al. Broad-host-range plasmid pJB658 can be used for industrial-level production of a secreted host-toxic single-chain antibody fragment in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(12):7033–7039. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7033-7039.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klumpp S, Scott M, Pedersen S, Hwa T. Molecular crowding limits translation and cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(42):16754–16759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310377110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott M, Gunderson CW, Mateescu EM, Zhang Z, Hwa T. Interdependence of cell growth and gene expression: origins and consequences. Science. 2010;330(6007):1099–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1192588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dennis PP. Effects of chloramphenicol on the transcriptional activities of ribosomal RNA and ribosomal protein genes in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1976;108(3):535–546. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(76)80135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang HC, Sherman MY, Kandror O, Goldberg AL. The molecular chaperone DnaJ is required for the degradation of a soluble abnormal protein in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(6):3920–3928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanemori M, Mori H, Yura T. Induction of heat shock proteins by abnormal proteins results from stabilization and not increased synthesis of sigma 32 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(18):5648–5653. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5648-5653.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prouty WF, Karnovsky MJ, Goldberg AL. Degradation of abnormal proteins in Escherichia coli. Formation of protein inclusions in cells exposed to amino acid analogs. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(3):1112–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z, Nimtz M, Rinas U. Global proteome response of Escherichia coli BL21 to production of human basic fibroblast growth factor in complex and defined medium. Eng Life Sci. 2017;17(8):881–891. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201700036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valgepea K, Adamberg K, Seiman A, Vilu R. Escherichia coli achieves faster growth by increasing catalytic and translation rates of proteins. Mol BioSyst. 2013;9(9):2344–2358. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70119k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sletta H, Tondervik A, Hakvag S, Aune TE, Nedal A, Aune R, et al. The presence of N-terminal secretion signal sequences leads to strong stimulation of the total expression levels of three tested medically important proteins during high-cell-density cultivations of Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(3):906–912. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01804-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Setubal JC, dos Santos P, Goldman BS, Ertesvag H, Espin G, Rubio LM, et al. Genome sequence of Azotobacter vinelandii, an obligate aerobe specialized to support diverse anaerobic metabolic processes. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(14):4534–4545. doi: 10.1128/JB.00504-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lieder S, Nikel PI, de Lorenzo V, Takors R. Genome reduction boosts heterologous gene expression in Pseudomonas putida. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:23. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito F, Tamiya T, Ohtsu I, Fujimura M, Fukumori F. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of the heat shock response in Pseudomonas putida. Microbiologyopen. 2014;3(6):922–936. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jakociunas T, Jensen MK, Keasling JD. CRISPR/Cas9 advances engineering of microbial cell factories. Metab Eng. 2016;34:44–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mougiakos I, Bosma EF, Ganguly J, van der Oost J, van Kranenburg R. Hijacking CRISPR-Cas for high-throughput bacterial metabolic engineering: advances and prospects. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;50:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bosdriesz E, Molenaar D, Teusink B, Bruggeman FJ. How fast-growing bacteria robustly tune their ribosome concentration to approximate growth-rate maximization. FEBS J. 2015;282(10):2029–2044. doi: 10.1111/febs.13258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klumpp S, Zhang Z, Hwa T. Growth rate-dependent global effects on gene expression in bacteria. Cell. 2009;139(7):1366–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balzer S, Kucharova V, Megerle J, Lale R, Brautaset T, Valla S. A comparative analysis of the properties of regulated promoter systems commonly used for recombinant gene expression in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farr SB, Kogoma T. Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55(4):561–585. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.561-585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.VanBogelen RA, Kelley PM, Neidhardt FC. Differential induction of heat shock, SOS, and oxidation stress regulons and accumulation of nucleotides in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169(1):26–32. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.26-32.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cardinale S, Joachimiak MP, Arkin AP. Effects of genetic variation on the E. coli host-circuit interface. Cell Rep. 2013;4(2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(12):6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramos-Gonzalez MI, Campos MJ, Ramos JL. Analysis of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 gene expression in the maize rhizosphere: in vivo [corrected] expression technology capture and identification of root-activated promoters. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(12):4033–4041. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4033-4041.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elbing K, Brent R. Media preparation and bacteriological tools. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2002;59:1. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0101s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoidal HK, Glaerum Svanem BI, Gimmestad M, Valla S. Mannuronan C-5 epimerases and cellular differentiation of Azotobacter vinelandii. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2(1):27–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(10):946–950. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zurawski G, Zurawski SM. Structure of the Escherichia coli S10 ribosomal protein operon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13(12):4521–4526. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.12.4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou K, Zhou L, Lim Q, Zou R, Stephanopoulos G, Too HP. Novel reference genes for quantifying transcriptional responses of Escherichia coli to protein overexpression by quantitative PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2011;12:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Growth rates (h−1) of E. coli BW25113 cells carrying pAG032. Table S2. Efficiencies of qPCR reaction (%) and R2 coefficients of determination of the standard curves for primer pairs used for amplification. Figure S1. Iinfluence of m-toluic acid (1 mM) on activity of (A) the XylS/Pm (only pAG032), (B) PrspJ and (C) Pibpfxs reporter units during cultivation of E. coli BW25113 transformed with three-gene version of the plasmid (pAG032) and two-gene version of the plasmid (pAG028). Cell were grown in M63 medium supplemented with glucose. The OD600nm normalized fluorescence values were calculated from measurements taken at the time point corresponding to 3 h after the induction. The data presented are from three independent biological replica (average ± SD). Please note that values of OD normalized fluorescence, not relative fluorescence, are given.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.