The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (hereinafter, Tobacco Control Act or the Act) provided the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with broad authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products to protect public health.1 The Act banned flavored cigarettes yet exempted menthol cigarettes.1 This exemption was coupled with a directive that the FDA seek a report and recommendation from the Tobacco Product Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) as a first order of business concerning the effect of menthol cigarettes on public health, with an emphasis on children and adolescents and racial/ethnic minority groups, particularly African Americans.1 The 2011 TPSAC report concluded that removing menthol cigarettes from the US market would benefit public health.2 A subsequent FDA evidence review and addendum in 2013 concluded it was “likely that menthol cigarettes pose a public health risk above that seen with non-menthol cigarettes.”3 Mounting evidence supports the detrimental effects of menthol cigarettes on population health, yet the FDA had not publicly pursued a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) or a final rule after issuing 2 advance notices of proposed rulemaking (ANPRMs; an ANPRM is a preliminary step in the regulatory process) on a potential ban on menthol cigarettes in 2013 and on flavors, including menthol, in 2018.

In October 2018, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb noted that it was “a mistake for the agency to back away on menthol.”4 On November 15, 2018, the FDA made a historic announcement that outlined a plan to ban menthol combustible tobacco products.5 Afterward, market analysts and tobacco industry representatives speculated that a menthol ban would never go into effect or would be delayed by years of litigation.6-8 Although the FDA has yet to publish a menthol product standard, tobacco companies are likely to challenge such a rule in court. We provide an overview of potential industry arguments and the scientific evidence supporting a menthol product standard.

Why Regulate Menthol?

Menthol is added to cigarettes to produce a cool, minty flavor with anesthetic properties that mask the harshness of tobacco smoke, making it easier to tolerate, especially for novice smokers.2,9 Menthol cigarettes comprise roughly one-third of the US tobacco cigarette market, and its market share has been increasing despite declining cigarette consumption, which is overwhelmingly attributed to decreases in nonmenthol cigarette use.10,11 These population trends are consistent with the TPSAC’s conclusion that menthol in cigarettes increases initiation and progression to tobacco smoking and decreases the likelihood of smoking cessation.3,12

FDA Authority to Regulate Menthol

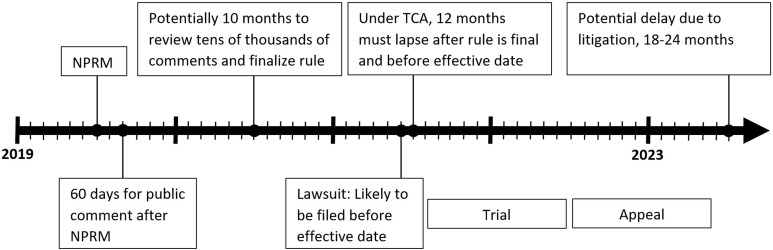

Section 907 of the Act authorizes the FDA to regulate menthol by issuing a product standard that would require tobacco companies to alter the content of their products. To establish a standard “appropriate for the protection of public health,” the FDA must consider scientific information concerning (1) the risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including users and nonusers; (2) the likelihood that existing users of tobacco products will stop using such products; and (3) the likelihood that those who do not use tobacco products will start using such products. The Act further requires the FDA to consider information about the proposed standard’s “technical achievability” and any “countervailing effects of the tobacco product standard…such as the creation of a significant demand for contraband.”1 Issuing an NPRM and a final rule banning menthol may take up to 2 years, absent litigation (Figure).

Figure.

Approximate timeline for issuance of a final rule and potential litigation, assuming a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) is issued on July 1, 2018. Abbreviation: TCA, Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act.1

Potential Tobacco Industry Arguments

The structure and text of the Act sets up 2 plausible arguments that the tobacco industry is likely to pursue. These arguments have been raised in statements to the press and in comments by RAI Services Company (“Reynolds”) and Altria Client Services (“Altria”) responding to the March 2018 ANPRM on flavors.6,7,13,14

Appropriate for the Protection of Public Health

After the FDA’s announcement in November, Altria’s general counsel said, “a total ban on menthol cigarettes or flavored cigars would be an extreme measure not supported by the science and evidence.”6 Although comments by Reynolds and Altria on the ANPRM raise numerous arguments, we address the 2 issues most likely to be featured in a lawsuit. Both Reynolds and Altria claim there is a consensus on the notion that menthol cigarettes are not more toxic than nonmenthol cigarettes.13,14 Although all cigarettes are effectively associated with premature morbidity and mortality for a substantial proportion of long-term users at the individual level,5,15-17 menthol cigarettes are more harmful than nonmenthol cigarettes at the population level, because they facilitate smoking initiation and nicotine dependence and impede cessation.2,3,18 Population-level effects are the FDA’s target for regulatory action.18 On other key issues, Reynolds and Altria arrive at conclusions that are diametrically opposed to the findings of the TPSAC, the 2013 FDA report, and most independent scientific researchers. In short, their interpretation of the science is that menthol smoking is not associated with (1) increased initiation and progression to regular cigarette smoking, (2) increased dependence, and (3) reduced success in smoking cessation.13,14

It is worth noting that Reynolds’ first step in combating an FDA regulation of menthol took place before the TPSAC report was finalized. Early in 2011, a Reynolds affiliate attempted to discredit the TPSAC’s report on menthol through litigation by alleging that 3 of its members had conflicts of interest.19 The lawsuit was successful in a district court, but it was reversed on appeal in 2016.19 This and other strategies presaged by Reynolds’ and Altria’s ANPRM comments evoked the industry’s decades-old strategies of disputing unfavorable science, planting doubt, and manufacturing conflicts of interest.20-22

Reynolds’ ANPRM comment relies on 4 studies published by its own paid consultants.14 Altria uses a strategy of elevating the level of proof required in scientific analysis to causation rather than association, arguing there is no “causal relationship between the use of menthol in cigarettes and smoking initiation…[;] between the use of menthol in cigarettes and increased dependence…[; and] between the use of menthol in cigarettes and smoking cessation.”13 However, the Act does not require causation, and the framework laid out by the 2011 TPSAC report highlights equipoise as the relevant requirement, in line with other government reviews.2,23 Thus, the relevant inquiry is whether pursuing a product standard is at least as likely to protect public health as taking no action. The weight of the evidence on the public health effect of menthol cigarettes is above equipoise, meeting many of the principles used to inform causal inference (eg, temporal relationship, consistency, coherence).24

The FDA will likely counter the tobacco industry’s arguments by relying on a strong consensus of leading scientists. Independent reviews support the notion that menthol cigarettes increase the number of persons who initiate and progress to smoking by making it easier to start and become addicted.11,12,25,26 Indeed, nearly 90% of all smokers start before age 18.27 In addition, teenage smokers start smoking with menthol cigarettes at disproportionately high rates.27-29 Once addicted, smokers of menthol cigarettes are more likely to remain long-term customers because menthol cigarette smokers have greater difficulty quitting than smokers of nonmenthol cigarettes.3,12,25 In addition, the tobacco industry has historically—and successfully—targeted menthol cigarettes to groups that now smoke menthol at disproportionately high rates,28-30 including adolescents, women, lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender/queer and questioning persons, African Americans, and Hispanic persons.11

Since publication of the 2013 FDA report, Villanti et al12 found that studies on menthol “bolster and augment earlier findings regarding the deleterious relationship between menthol cigarette use, youth smoking initiation, and nicotine dependence.” This comprehensive 2017 review of the scientific evidence found “more than sufficient evidence to establish a positive relationship between menthol cigarettes and (1) increased youth smoking initiation, (2) increased nicotine dependence, and (3) decreased adult cessation.”12 These conclusions track the Act’s standard and contradict the tobacco industry’s main contentions. Moreover, despite decreases in the use of nonmenthol cigarettes, research indicated that the market share of menthol cigarettes has grown in recent years—increasing among young adults and remaining constant among adolescents and adults—heightening the importance of addressing menthol cigarettes.11,12

Given the weight of the scientific evidence favoring a menthol ban, a court is likely to find that a regulation banning combustible menthol tobacco products is appropriate for the protection of public health. Although scientific debate outlined previously over menthol is likely to play a pivotal role in determining the outcome of the case, the tobacco industry will likely use the threat of illicit trade to undermine and distract from this part of the analysis.

Countervailing Effects of Demand for Contraband

The FDA must consider “information concerning the countervailing effects of the tobacco product standard on the health of adolescent tobacco users, adult tobacco users, or non-tobacco users such as the creation of a significant demand for contraband.”1 This standard is lenient because it merely requires the FDA to consider the effect of illicit trade on a proposed product standard.1 A court would likely reason that illicit trade should warrant striking down a product standard only if the magnitude of illicit trade is so substantial that the product standard would no longer protect public health. Notably, the Act did not conclude that the threat of illicit markets is a reason to refrain from regulation; rather, it empowered the FDA to protect against such a threat.1,31 For example, Section 920 of the Act grants the FDA authority to implement a track-and-trace program to combat illicit trade.1

Reynolds and Altria argue that a ban on menthol cigarettes would increase the demand for illicit menthol cigarettes and lead to consequences such as (1) a flood of unregulated cigarettes on the market; (2) increased sales to young persons; (3) smokers making their own menthol cigarettes; (4) criminalizing smoking preferences, with a disproportionate effect on African Americans, and increasing criminal activity; and (5) a loss of tax revenue and Master Settlement Agreement payments.13,14 This litany of arguments is not surprising. The tobacco industry consistently uses the specter of illicit trade as a tool to combat various types of regulation, including regulations on graphic warning labels, tax increases, and restrictions on flavors.31 Comparisons between tobacco industry estimates of illicit trade and estimates of independent researchers show that industry estimates are likely to overestimate actual behavior.32,33 Industry figures are also consistently characterized by a lack of transparency in describing methodologies and presenting findings.32 Nevertheless, the 5 arguments warrant attention.

1. Flood of unregulated cigarettes on the market

A menthol ban may actually decrease illicit trade. In the United States, a large portion of illicit trade involves cross-border sales whereby bootleggers exploit price disparities by buying cigarettes in states with low taxes and trafficking them to localities with substantially higher prices.34 For this tax-driven illicit interstate marketplace, the supply of low-cost cigarettes is abundant. With some of the highest cigarette prices nationwide, New York City may be the largest market for contraband cigarettes in the United States.35 In New York City, 48% of cigarette smokers smoke menthol cigarettes.36 Virginia is the most common source of cigarettes trafficked into New York City.37 One study found that more than 80% of the illicit cigarettes found in the South Bronx are Newport menthol cigarettes,38 a phenomenon that is also prevalent in Harlem.39 In the event of a ban on menthol cigarettes, the supply for what is likely the most commonly bootlegged cigarette brand in New York City would evaporate, potentially resulting in an overall decrease in New York City’s illicit market.

Without traditional sources of legally taxed, domestic menthol cigarettes, traffickers would have to find new illicit sources. Illicit domestic production is likely to pose substantial financial and legal risks to the producers. Reliance on international sources is likely to increase the costs of evading US customs and other law enforcement authorities. Although some menthol cigarette smokers would likely seek out illicit menthol cigarettes, one study suggests that most menthol cigarette smokers would be unlikely to pay a premium for menthol cigarettes or contend with logistical obstacles to obtain them.40

Even if sources of illicit menthol cigarettes emerge, it would be improbable for illicit production and distribution to rival the current consumption of menthol cigarettes, estimated at 4.5 billion packs in 2016.41,42 Contrary to industry predictions, after Nova Scotia implemented a menthol ban in 2015—the first Canadian province to do so—there was no surge in illicit menthol cigarettes.43 (Canada implemented a national ban on menthol cigarettes in 2017.) Furthermore, to the extent that menthol cigarette smokers quit or migrate to other sources of nicotine, such as nonmenthol cigarettes or electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), the demand for illicit menthol tobacco products would decline.

In addition to creating a track-and-trace system, the FDA can disrupt trafficking into the United States through intergovernmental cooperation. For example, the FDA’s Office of Criminal Investigations can coordinate with US Customs and Border Protection and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to improve enforcement at certain ports of entry and other strategically selected points. The FDA can also coordinate with state attorneys general to pressure shipment companies (eg, UPS, FedEx) to increase compliance with a ban on online cigarette sales.44-46

2. Increased sales to young persons

The theory that a menthol ban will lead to an increase in cigarette sales to young persons is premised on several assumptions. First, it is based on a faulty assumption that the volume of illicit menthol cigarettes will increase. Second, it assumes that increasing the distribution of illicit cigarettes outside of regulated retail outlets will increase access to tobacco products for young persons. There is no evidence that this is likely to happen. Third, it fails to consider trends in tobacco use among young persons47,48 and data on the effect of the FDA’s 2009 ban on flavored cigarettes.49,50 These data suggest that although a ban on menthol-flavored cigarettes may contribute to a migration of young persons to e-cigarettes—in which menthol presumably would be allowed as a flavor under an FDA product standard51,52—it will likely reduce the overall probability of tobacco use among young persons.

3. Smokers making their own menthol cigarettes

Internal tobacco industry documents reveal that, in terms of chemistry, manipulating menthol is challenging because of its high volatility, and tobacco companies worked for decades to optimize menthol yields, filing numerous patent applications since the 1960s.9 It is not credible to speculate that homemade menthol cigarettes can approximate commercially available products or that people will “DIY” (ie, make their own menthol cigarettes) on a large scale.

4. Criminalizing menthol cigarettes and increased criminal activity

Reynolds’ contention that a menthol ban will “criminalize smoking preferences,” with a disproportionate effect on African Americans (eg, police arresting young African Americans, inflaming racial tensions, and leading to violence), is phrased ambiguously. However, statements made by Reynolds’ surrogates suggest that it is part of a strategy calculated to stoke fear that a menthol ban will lead to conflict, and inevitably violence, between police and black teenagers.53 This opposition strategy, however, is not founded in any empirical data and ignores basic realities about tobacco control enforcement. The FDA’s product standard would not criminalize anything. Rather, it would cut off the supply of menthol combustibles at a manufacturing level. The notion that consumers, especially African American consumers, would be the target of FDA enforcement actions is unfounded given that civil penalties are issued to retailers, not consumers, for violating FDA regulations related to tobacco. Furthermore, no evidence indicates that a menthol ban would increase African American participation in illicit markets.

Reynolds argues that a menthol ban would result in an overall increase in criminal activity through an increase in illicit sales, an increase in sales to adolescents, and an increase in other criminal activity that may be funded by profits from illicit tobacco sales. These predictions are speculative, and although the FDA should consider them seriously, these predictions do not appear to be compelling reasons for the FDA to refrain from banning menthol cigarettes.

5. Loss of tax revenue and Master Settlement Agreement payments

Reynolds and Altria contend that a ban on menthol cigarettes would result in a dramatic loss of tax revenue and Master Settlement Agreement payments. Indeed, the FDA must consider the current and future costs and benefits of a rule.54 Altria estimates that $63 billion is generated annually from excise taxes, payments from the Master Settlement Agreement and Previously Settled State Agreements, sales taxes, and taxable corporate and personal income from tobacco-related businesses and jobs.13 A portion of this $63 billion is from sales of menthol cigarettes. Altria also describes how a menthol ban would have a negative effect on tobacco growers and retailers.13 However, neither Altria nor Reynolds refer to the total economic cost of smoking, which is approximately $326 billion annually, including $170 billion55 in direct medical care for adults and $156 billion24 in lost productivity caused by premature death and exposure to secondhand smoke. A court is unlikely to be persuaded that lost revenue weighs against a menthol ban in light of the overwhelming total economic costs of smoking.

Overall, it seems unlikely that the tobacco industry will articulate persuasive arguments that illicit trade would nullify the public health benefits of a menthol ban. As a result, illicit trade seems unlikely to shift a court’s assessment of the weight of the scientific evidence.

Likely Delay Due to Litigation

A legal challenge to a ban on menthol cigarettes is likely to delay implementation of the product standard. First, the industry will likely argue that the FDA should be blocked from implementing the rule. To do so, the tobacco industry plaintiffs must establish that they are likely to prevail on the merits, they are likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, that a balance of hardships weighs in their favor, and that the public interest favors an injunction.56 Even if a court finds that the FDA is likely to prevail on the merits, other factors may weigh in favor of an injunction. Second, industry lawyers may argue that a trial, possibly by jury, must decide which side has more credible experts. Depending on the judge assigned to the case, among other factors, the duration of the pretrial period and a trial, if necessary, can vary widely. Regardless of which side prevails at trial, appeals typically will follow, adding months or years to the process. Although implementation of a rule before a trial or during an appeal is possible, it is far from certain. Overall, the legal process may play out over several years.

Conclusion

The FDA’s plan to ban combustible menthol cigarettes has the potential to save lives. However, given menthol cigarettes’ sizable market share, the tobacco industry is likely to oppose the move in court. The weight of the scientific evidence supporting a menthol ban, including several independent evidence reviews, has only grown stronger during the past several years. In addition, emerging evidence from menthol bans in US municipalities and Canada are likely to solidify support for such a product standard. Industry arguments about illicit trade arguments are unlikely to distract a court from the weight of the scientific evidence. Therefore, a court is likely to uphold a menthol ban as appropriate for the protection of public health.2,3,12,57 A more difficult question is how long litigation may delay implementation. Increases in menthol market share highlight the urgency of implementation.

One novel element of this controversy is that it would take place in the context of the FDA’s comprehensive nicotine framework.58 The cornerstone of that plan involves reducing nicotine levels in cigarettes to nonaddictive levels, leaving e-cigarettes as a less harmful source of nicotine for tobacco cigarette smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit.59 If the FDA sets a nicotine reduction standard for combustible tobacco products after a ban on menthol cigarettes goes into effect,59 a court may consider that both product standards (menthol and low nicotine) are part of a plan to reduce the use of combustible tobacco products, and if both steps are implemented together, the FDA can likely make an even stronger case that a ban on menthol cigarettes is a sensible part of a plan that, as a whole, is appropriate for the protection of public health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health under awards U54CA229973 (Cristine D. Delnevo, Kevin R. J. Schroth, and Marin Kurti) and R21DA046333, P20GM103644, and U54DA036114 (Andrea C. Villanti). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The study sponsor had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the article; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Pub L No. 111-31, 123 Stat 1776 (2009).

- 2. Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol cigarettes and public health: review of the scientific evidence and recommendations. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170405201731/https:/www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM269697.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 3. US Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary scientific evaluation of the possible health effects of menthol versus nonmenthol cigarettes. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/ucm361598.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 4. Kaplan S. Altria to stop selling some e-cigarette brands that appeal to youths. The New York Times. October 25, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/25/health/altria-vaping-ecigarettes.html. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 5. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on proposed new steps to protect youth by preventing access to flavored tobacco products and banning menthol in cigarettes [news release]. Washington, DC: US Food and Drug Administration; 2018. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/UCM625884.htm. Accessed December 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spiezio C. Altria GC expresses opposition on new FDA proposal to ban menthol cigarettes. Corporate Counsel. November 15, 2018. https://www.law.com/corpcounsel/2018/11/15/altria-gc-expresses-opposition-on-new-fda-proposal-to-ban-menthol-cigarettes/. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 7. Maloney J, McGinty T. FDA seeks ban on menthol cigarettes: Big Tobacco defends the flavored cigarettes and raises the possibility of a legal battle. The Wall Street Journal. Updated November 15, 2018 https://www.wsj.com/articles/big-tobacco-warns-it-may-fight-fda-over-a-menthol-ban-1542277800. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 8. Wolf C. Big Tobacco not sweating proposed FDA curb on flavored cigarettes. CBS News. November 26, 2018 https://www.cbsnews.com/news/big-tobacco-not-sweating-fda-proposed-curbs-on-menthol-flavored-cigarettes/. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 9. Yerger VB, McCandless PM. Menthol sensory qualities and smoking topography: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii37–ii43. doi:10.1135/tc.2010.041988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Delnevo CD, Villanti AC, Giovino GA. Trends in menthol and non-menthol cigarette consumption in the USA: 2000-2011. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e154–e155. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the prevalence and correlates of menthol cigarette use in the USA, 2004-2014. Tob Control. 2016;25(suppl 2): II14–II20. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS, Gagosian SY, Abrams DB. Menthol cigarettes and the public health standard: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):983 doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4987-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Altria Client Services. Comment from Altria client services. Fed Reg. 2018;83(55):12294. [Google Scholar]

- 14. RAI Services Company. Comment from RAI services company. Fed Reg. 2018;83(55):12294. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Munro HM, Tarone RE, Wang TJ, Blot WJ. Menthol and non-menthol cigarette smoking: all-cause deaths, cardiovascular disease deaths, and other causes of death among blacks and whites. Circulation. 2016;133(19):1861–1866. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.115.020536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones MR, Tellez-Plaza M, Navas-Acien A. Smoking, menthol cigarettes and all-cause, cancer and cardiovascular mortality: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77941 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones MR, Apelberg BJ, Samet JM, Navas-Acien A. Smoking, menthol cigarettes, and peripheral artery disease in US adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;15(7):1183–1189. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Villanti AC, Giovino GA, Burns DM, Abrams DB. Menthol cigarettes and mortality: keeping focus on the public health standard. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):617–618. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v US Food and Drug Administration. 810 F.3d 827 (D.C. Circuit 2016).

- 20. Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):259–294. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brandt AM. Inventing conflicts of interest: a history of tobacco industry tactics. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):63–71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. United States of America v Philip Morris USA, Inc. 449 F. Supp.2d 1 (D.D.C. 2006).

- 23. Bodurow CC, Samet JM, eds. Improving the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Villanti AC, Vargyas EJ, Niaura RS, Beck SE, Pearson JL, Abrams DB. Food and Drug Administration regulation of tobacco: integrating science, law, policy, and advocacy. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(7):1160–1162. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Office of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Delnevo CD, Gundersen DA, Hrywna M, Echeverria SE, Steinberg MB. Smoking-cessation prevalence among US smokers of menthol versus non-menthol cigarettes. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4):357–365. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD, et al. Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: is menthol slowing progress? Tob Control. 2015;24(1):28–37. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hersey JC, Ng SW, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Are menthol cigarettes a starter product for youth? Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(3):403–413. doi:10.1080/14622200600670389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hersey JC, Nonnemaker JM, Homsi G. Menthol cigarettes contribute to the appeal and addiction potential of smoking for youth. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl 2):S136–S146. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Ambrose BK, et al. Flavored tobacco product use in youth and adults: findings from the first wave of the PATH Study (2013-2014). Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):139–151. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Farley T, Hansen CW, Brown NA, et al. Citizen petition to U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FDA-2013-P-0285-0001. Published 2013. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 32. Gallagher AWA, Evans-Reeves KA, Hatchard JL, Gilmore AB. Tobacco industry data on illicit tobacco trade: a systematic review of existing assessments [published online August 16, 2018]. Tob Control. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Trade Organization. Australia—certain measures concerning trademarks, geographical indications and other plain packaging requirements applicable to tobacco products and packaging. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds467_e.htm. Published 2018. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 34. Barker DC, Wang S, Merriman D, Crosby A, Resnick EA, Chaloupka FJ. Estimating cigarette tax avoidance and evasion: evidence from a national sample of littered packs. Tob Control. 2016;25(suppl 1):i38–i43. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. LaFaive MD, Nesbit T, Drenkard S. Cigarette smugglers still love New York and Michigan, but Illinois closing in. Mackinac Center for Public Policy. https://www.mackinac.org/20900. Published 2015. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 36. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2015. New York City Community Health Survey (NYC CHS). https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/episrv/chs2015survey.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 37. Davis KC, Grimshaw V, Merriman D, et al. Cigarette trafficking in five northeastern US cities. Tob Control. 2014;23(e1):e62–e68. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kurti M, von Lampe K, Johnson J. The intended and unintended consequences of a legal measure to cut the flow of illegal cigarettes into New York City: the case of the South Bronx. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):750–756. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shelley D, Cantrell MJ, Moon-Howard J, Ramjohn DQ, VanDevanter N. The $5 man: the underground economic response to a large cigarette tax increase in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1483–1488. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.079921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. von Lampe K, Kurti M, Johnson J, Rengifo AF. “I wouldn’t take my chances on the street”: navigating illegal cigarette purchases in the South Bronx. J Res Crime Delinq. 2016;53(5):654–680. doi:10.1177/0022427816637888 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Department of the Treasury, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Statistical report—tobacco, 2016. https://www.ttb.gov/statistics/2016/201612tobacco.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 42. Federal Trade Commission. Cigarette report for 2016. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2016-federal-trade-commission-smokeless-tobacco-report/ftc_cigarette_report_for_2016_0.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 43. Stoklosa M. No surge in illicit cigarettes after implementation of menthol ban in Nova Scotia [published online October 8, 2018]. Tob Control. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. FedEx to strengthen policies restricting cigarette shipments [press release]. Albany, NY: New York State Office of the Attorney General; 2006. https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/fedex-strengthen-policies-restricting-cigarette-shipments. Accessed December 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haag M. Judge orders UPS to pay $247 million for illegally shipping cigarettes. The New York Times. May 25, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/25/nyregion/ups-cigarettes-lawsuit.html. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 46. City of New York v FedEx Ground Package System. No. 13 Civ 9173 (ER) (2017).

- 47. Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu SS, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2016 [published correction appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(28):765]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(23):597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cullen KA, Ambrose BD, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(45):1276–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Klein SM, Giovino GA, Barker DC, Tworek C, Cummings KM, O’Connor RJ. Use of flavored cigarettes among older adolescent and adult smokers: United States, 2004-2005. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(7):1209–1214. doi:10.1080/14622200802163159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Courtemanche CJ, Palmer MK, Pesko MF. Influence of the flavored cigarette ban on adolescent tobacco use. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):e139–e146. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wackowski OA, Delnevo CD, Pearson JL. Switching to e-cigarettes in the event of a menthol cigarette ban. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1286–1287. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsai J, Walton K, Coleman BN, et al. Reasons for electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(6):196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. DeLeon-Foote R. A discussion on menthol bans and criminalization of black communities. https://countertobacco.org/a-discussion-on-menthol-bans-and-criminalization-of-black-communities. Published 2017. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 54. Improving regulation and regulatory review. Executive Order No. 13563. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2011/01/21/2011-1385/improving-regulation-and-regulatory-review. Published 2011. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 55. Xu X, Bishop EE, Kennedy SM, Simpson SA, Pechacek TF. Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking: an update. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(3):326–333. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gordon v Holder. 721 F.3d 638 (D.C. Cir. 2013).

- 57. Chaiton M, Schwartz R, Cohen JE, Soule E, Eissenberg T. Association of Ontario’s ban on menthol cigarettes with smoking behavior 1 month after implementation. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):710–711. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA’s comprehensive plan for tobacco and nicotine regulation. https://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/newsevents/ucm568425.htm. Published 2019. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 59. Office of the Federal Register. Tobacco product standard for nicotine level of combusted cigarettes. Fed Reg. 2018;83(52):11818. [Google Scholar]