Increased oxidative stress (OS) due to ubiquitous exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) can affect the quality of oocytes by inducing apoptosis and hampering granulosa cell mediated steroidogenesis.

Increased oxidative stress (OS) due to ubiquitous exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) can affect the quality of oocytes by inducing apoptosis and hampering granulosa cell mediated steroidogenesis.

Abstract

Increased oxidative stress (OS) due to ubiquitous exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) can affect the quality of oocytes by inducing apoptosis and hampering granulosa cell mediated steroidogenesis. This study was carried out to investigate whether DEHP induced OS affects steroidogenesis and induces apoptosis in rat ovarian granulosa cells. OS was induced by exposing granulosa cells to various concentrations of DEHP (0.0, 100, 200, 400 and 800 μM) for 72 h in vitro. Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidative stress (OS), mitochondrial membrane potential, cellular senescence, apoptosis, steroid hormones (estradiol & progesterone) and gene expression were analyzed. The results showed that an effective dose of DEHP (400 μg) significantly increased OS by elevating the ROS level, mitochondrial membrane potential, and β-galactosidase activity with higher mRNA expression levels of apoptotic genes (Bax, cytochrome-c and caspase3) and a lower level of an anti-apoptotic gene (Bcl2) as compared to the control. Further, DEHP significantly (P > 0.05) decreased the level of steroid hormones (estradiol and progesterone) in a conditioned medium and this effect was reciprocated with a lower expression (P > 0.05) of steroidogenic responsive genes (Cyp11a1, Cyp19A1, Star, ERβ1) in treated granulosa cells. Furthermore, co-treatment with N-Acetyl-Cysteine (NAC) rescues the effects of DEHP on OS, ROS, β-galactosidase levels and gene expression activities. Altogether, these results suggest that DEHP induces oxidative stress via ROS generation and inhibits steroid synthesis via modulating steroidogenic responsive genes, which leads to the induction of apoptosis through the activation of Bax/Bcl-2-cytochrome-c and the caspase-3-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in rat granulosa cells.

Introduction

Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is one of the most common endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), and widely used to make vinyl plastics softer and more flexible.1–3 DEHP is one of the highest volume chemicals produced with an estimated 5% annual growth due to its increasing manufacturing demand worldwide.4,5 It is believed that heat and either acidic or basic conditions accelerate the hydrolysis of DEHP monomers, leading to their release into food and liquid that gets integrated as a part of the food chain of humans. In the past few years, several reports on the cytotoxicity of DEHP in mammals were published. Because of its estrogenic activity, DEHP could cause several reproductive disorders in humans. It is reported that women are more prone to phthalate exposure than men, because of the presence of phthalates in their personal care products.6,7 Therefore, DEHP can be found in developmental and reproductive organs of women.8 Recent studies have demonstrated the presence of DEHP metabolites, mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) in human urine samples,9,10 amniotic fluid,11 breast milk12 and ovarian follicular fluid13 indicating that even little exposure to DEHP in daily life from any sources may reflect a potential risk factor for ovarian physiology.

The mammalian ovaries are metabolically active organs consisting of oocytes, granulosa and theca cells. Growth and development of follicles is directly associated with steroid hormones which is produced by granulosa cells during folliculogenesis. In addition, steroids are essential for maintaining normal ovarian physiology.14 The first stage of steroidogenesis is steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR)-mediated transportation of cholesterol into the mitochondria. In mammals, steroid hormones are synthesized from cholesterol by luteinizing hormone (LH) responsive theca cells, and then converted into estrogens by granulosa cells in the presence of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) with the help of 19α-hydroxylase (CYP19A1).15,16 During this process, any functional disruption could induce apoptosis in granulosa cells as a result of disrupting ovarian steroidogenesis. Previous studies reported that the exposure to DEHP leads to the depletion of the primordial follicle pool, affects oocyte maturation, decreases sex steroid hormone production, changes the DNA methylation status of imprinted genes and induces transgenerational effects on female reproduction.17–21

Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between the generation and removal of ROS in the system, leading to DNA damage and oxidative modification of proteins. It is reported that DEHP induces apoptosis and increases the ROS level in cumulus cells (CCs) without affecting oocyte maturation in horse and GC-2spd cells.17,22 Further, it has been shown that excess ROS affects angiogenesis, which is critical for follicular growth, oocyte maturation and corpus luteum formation.23,24 However, it is not clear that whether DEHP induced apoptosis is mediated by the increased ROS level in granulosa cells. Therefore, a possibility exists that DEHP through the mitochondria could induce generation of ROS in granulosa cells, which induces apoptosis and modulates steroid responsive gene expression thereby hampering steroid production. However, there is no evidence to support this possibility. Therefore, this study was designed to examine whether the in vitro treatment of DEHP induces the generation of ROS and if so, whether DEHP-induced apoptosis is mediated through the mitochondrial pathway as a result of the disruption of ovarian steroidogenesis. For this purpose, in vitro studies were carried out to analyze morphological apoptotic changes, intracellular ROS, OS, β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) levels, mitochondrial membrane potential, gene expression, apoptosis and the level of steroid hormones (estradiol & progesterone) in DEHP exposed granulosa cells.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Chemicals used in this study were procured from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP; cat no. 36735; 1G) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). The stock solution of DEHP (2.56 mM) was prepared by diluting 1 mg of DEHP powder in 1.0 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The stock solution was immediately aliquoted and kept at –20 °C until use.

Experimental animals

Sexually mature female rats (100 ± 5 g body weight) of the Charles-Foster strain were purchased from the Central Animal House, Institute of Medical Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi and housed in air-conditioned, light controlled rooms, with food and water ad libitum. The animal experiments were carried out as per the regulations provided by the Animal Ethical Committee of the Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee of the University (vide letter No. Dean/2015/CAEC/1517 dated 21/12/2015).

Preparation of the culture medium and DEHP working concentrations

The culture medium (TCM-199) was prepared as per a published protocol.24 The culture medium-199 was supplemented with sodium bicarbonate (0.035% w/v), penicillin (100 IU ml–1) and streptomycin (100 mg ml–1) and pH was adjusted to 7.2 ± 0.10. The working concentrations (0, 100, 200, 400 and 800 μM) of DEHP were prepared by diluting the stock solution (2.56 mM) with a freshly prepared working culture medium. The final concentrations of DEHP did not alter the osmolarity (290 ± 5 mOsmol) and pH 7.2 ± 0.10 of the culture medium. Since DMSO was used as a solvent for DEHP, DMSO (0.01% v/v), representing the final DMSO without DEHP was used in the control group. N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was used at a concentration of 5 mM, which is reported to be an effective antioxidant and free-radical scavenger protecting against oxidative damage in mouse oocytes and other cell types.25,26 The impact of NAC was analyzed against only the effective dose of DEHP (400 μm) in all the experimental setup.

Collection and culture of granulosa cells from preovulatory COCs

The granulosa cells (mural as well as cumulus cells) were isolated from preovulatory COCs using 0.01% hyaluronidase in culture medium as per the established protocol.24 In detail, granulosa cells were washed 3 times in fresh culture medium by centrifugation at 300g for 5 min to remove enzyme activity and blood cells. The washed granulosa cells were cultured in TCM-199 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic solution (HiMedia, Pvt. Ltd, India) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 (Model; Galaxy 170 R, New Brunswick, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) at 37 °C. The cells were sub-cultured every 5–6 days using trypsin-EDTA solution (0.25%) and periodically evaluated using a phase contrast microscope (EVOS-FL, Life Technologies).

MTT assay

To determine the cellular cytotoxicity of DHEP, the colorimetric MTT metabolic activity assay was performed. In detail, second passage granulosa cells (1 × 106 cells) were cultured in TCM-199 supplemented with different concentrations of DEHP (0.0, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μM), NAC (5 mM) and DEHP (400 μM) + NAC (5 mM) for 72 h in a CO2 incubator as per the established protocol.27 The cells that were cultured with medium (TCM-199) only served as a control. After the incubation period, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then 20 μl of MTT solution (5 mg ml–1 in PBS) along with 100 μl of culture medium were added in each well and incubated for 4 h in the CO2 incubator. After 4 h of incubation, DMSO (100 μl) was added to dissolve formazan crystals and then the absorbance intensity was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-RAD 680, USA) at 590 nm. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the relative cell viability (%) was expressed as a percentage. EC50 values (50% effective concentration) were obtained with the help of GraphPad prism 4.0 (GraphPad software, USA) using non-linear regression analysis.

In vitro effects of DEHP on the morphological changes in granulosa cells

Based on the result of the MTT assay, we selected 400 μM DEHP dose and 72 h of incubation time to conduct further experiments as per the established procedure.28 Second passage granulosa cells (1 × 106 cells) were cultured in TCM-199 with or without an optimum effective dose of DEHP (400 μM) and with a combination of DEHP (400 μM) + NAC (5 mM) for 72 h in the CO2 incubator. After 72 h of incubation, granulosa cells were analyzed for morphological changes, oxidative stress/hypoxia, ROS level, β-galactosidase activity (cellular senescence), mitochondrial membrane potential (JC1 staining), apoptosis, gene expression and steroid hormone (estradiol & progesterone) levels.

Acridine orange/propidium iodide nuclear staining

Acridine orange (AO) and propidium iodide (PI) staining was performed to confirm the cellular viability as a result of the morphological changes in the DEHP treated granulosa cells. In brief, second passage granulosa cells (1 × 106 cells) were cultured in TCM-199 supplemented with an optimum effective dose of DEHP (400 μM) and a combination of DEHP (400 μM) + NAC (5 mM) for 72 h in a CO2 incubator. Cells that were cultured with medium (TCM-199) only served as a control. Cells from all groups were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 20 min. Then the cells were stained with AO/PI (10 μg ml–1 in PBS) for 10 min in triplicate. The photographs were taken at 200× magnification under an inverted fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL, Life Technologies). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Oxidative stress and hypoxia detection

The redox status of the control as well as the DEHP treated granulosa cells was assessed using an oxidative stress/hypoxia (ENZ-51042; Enzo Life Sciences, NY, USA) assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, after 72 h of treatment, cells with alone DEHP (400 μM) and in combination (DEHP 400 μM + NAC 5 mM) were washed with PBS and incubated with a hypoxia/oxidative stress detection mix for 30 min at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS and observed under a fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL, Life Technologies). As per the manufacturer's instructions, oxidative stress was detected using a FITC filter at 490/525 nm while hypoxia was detected using a Texas red filter at a 596/670 nm wavelength using an inverted fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL, Life Technologies). The ROS inducer (pyocyanin) and hypoxia inducer (deferoxamine, DFO) were used as a positive control and a sample without a detection mix is used as a negative control. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Analysis of the ROS level

After 72 h of treatment, granulosa cells with alone DEHP (400 μM) and in combination (DEHP 400 μM + NAC 5 mM), including the control group were trypsinized and collected in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube separately. Further, the cells were incubated with 10 μM dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Beyotime, Nantong, China) at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing 3 times using serum-free culture medium, the cells were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL, Life Technologies) as per the manufacturer's instructions. DCF fluorescence was detected at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm using an inverted fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL, Life Technologies). The experiment was repeated three times to confirm the results.

Cellular senescence assay (β-galactosidase activity)

The identification of senescent cells is based on an increased level of lysosomal β-galactosidase activity. The cellular senescence assay was performed as per the manufacturer's protocol (ENZ-129; Enzo Life Sciences, NY, USA) with little modifications. In brief, after 72 h of treatment, cells with alone DEHP (400 μM) and in combination (DEHP 400 μM + NAC 5 mM) were washed with pre-chilled PBS and lysed in lysis buffer, and centrifuged at 3000× for 10 min. 50 μl of supernatant (cell lysate) from DEHP treated and control groups were transferred to a 96-well plate in triplicate. 50 μl of 2× assay buffer were added in each well and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. Finally, 100 μl of stop solution were added and the intensity of fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (Micro Scan MS5608A, ECIL, Hyderabad, India) at a 360/465 nm wavelength. The value of β-galactosidase activity was evaluated from three independent experiments.

Assessment of the mitochondrial membrane potential

The DEHP treated and control group granulosa cells were stained with an inner mitochondrial membrane potential reporter JC-1 (1 μM) dye (5,5,6,6-tetra-chloro-1,1,3,3-tetra-ethyl-benz-imidazolo-carbocyanine iodide (BD Bioscience) to analyze the membrane potential as per the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, after 72 h of treatment, granulosa cells with alone DEHP (400 μM) and in combination (DEHP 400 μM + NAC 5 mM) were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with the JC-1 dye prepared in JC-1 buffer for 10 min. Images were captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL, Life Technologies) and analyzed for the mitochondrial membrane potential. The mean value of fluorescence was normalized to the area of measurement using the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) method.29 Values are expressed as total red CTCF from three replicates.

Apoptosis assay

After 72 h of treatment, granulosa cells with alone DEHP (400 μM) and in combination (DEHP 400 μM + NAC 5 mM) were evaluated for apoptosis using an annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit. The treated granulosa cells were harvested and incubated with 200 μl of binding buffer (HEPES buffered PBS supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2), 2 μl of annexin V-FITC and 5 μl of PI at room temperature for 15 min in the dark, following the manufacturer's instructions. After a final wash in PBS, samples were excited by a light wavelength of 488 nm with barrier filters of 525 nm and 575 nm for FITC fluorescence and PI detection, respectively. Data were analyzed and plotted for annexin V-FITC using appropriate software.

Estimation of estradiol-17β and progesterone by ELISA

The conditioned medium from all treatment groups DEHP (400 μM) and in combination (DEHP 400 μM + NAC 5 mM) were collected after 72 h of treatment. The estradiol 17β and progesterone concentrations were evaluated using the ELISA kit purchased from Elabscience, MD, USA, and followed the instruction as per the kit protocol. In brief, 50 μl of standards and samples were added to pre-coated microwell plates in duplicate. Thereafter, 50 μl of a 17β estradiol-HRP and progesterone conjugate was added to each well, mixed well and then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C separately. At the end of the incubation period, the respective microplates were rinsed and flicked 5 times with wash buffer. After washing, 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Thereafter, 50 μl of stop solution was added to each well, mixed for 30 s and the absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Micro Scan, ECIL, India) within 15 min. All samples were run in one assay to avoid inter-assay variation and the intra-assay variation was 1.4%. The data of estradiol 17β and progesterone concentration were presented in pg ml–1 and ng ml–1 respectively and repeated at least three times.

Gene expression analysis by PCR

After 72 h of treatment, granulosa cells with alone DEHP (400 μM) and in combination (DEHP 400 μM + NAC 5 mM) were harvested to evaluate the mRNA expression. mRNA was isolated from all treatment groups using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and then reversed transcribed using the cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific Inc.). RT-PCR for different genes including Bax, caspase-3, Bcl2, Cyp11a, Cyp19A1, ER-β, and GAPDH were performed using the Maxima hot start Green master mix (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) in a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). The gene sequences of the primers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sequences of primer sets used for the gene expression analysis.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| GAPDH | GGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACT | AGGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA |

| Bax | AGGATGCGTCCACCAAGAA | CAAAGTAGAAGAGGGCAACCAC |

| Bcl-2 | CACCCCTGGCATCTTCTCCTT | AGCGTCTTCAGAGACAGCCAG |

| Cyt-c | GAGGCAAGCATAAGACTGGA | TACTCCTCAGGGTATCCTC |

| Caspase-3 | TGACTGGAAAGCCGAAACTC | GCAAGCCATCTCCTCATCAG |

| Cyp11A1 | CGATACTCTTCTCATGCGAG | CTTTCTTCCAGGCATCTGAAC |

| Cyp19A1 | GACACATCATGCTGGACACC | CAAGTCCTTGACGGATCGTT |

| Star | CTTGGCTGCTCAGTATTGAC | TGGTGGACAGTCCTTAACAC |

| ER-β1 | TAGGCACCCAGGTCTGCAAT | ACCAAGGACTCTTTTGAGGT |

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was chosen to estimate the transcript level of analyzed genes according to Dubey et al. (2012).30 To control the variation in the efficiencies of the RT step among different experimental samples, mRNA concentrations of GAPDH, a housekeeping gene, presumed to be expressed at constant amounts in all samples, were also calculated, along with the mRNA concentrations of targeted genes, by densitometry analysis using ImageJ 1.43U software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland). Relative expression was determined as arbitrary units, defined as the ratio of the mRNA level to the corresponding GAPDH mRNA level after the subtraction of the background intensity [value = (intensity; gene of interest-intensity; background)/(intensity; GAPDH intensity; background)]. The mean values of three measurements for each gene in each sample band were taken for analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were expressed as means ± SEM from at least three separate experiments. Multiple comparisons between treatment groups were made using ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc comparison. Comparison between two groups was done using Student's t-test. A probability of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

The fluorescence intensity was analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.44 from the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, USA). For this purpose, minimum three different areas of each figure as well as its corresponding background were selected. Relative expression was determined as arbitrary units, defined as the ratio of the mRNA level to the corresponding GAPDH mRNA level after the subtraction of the background intensity using the established procedure.30

Results

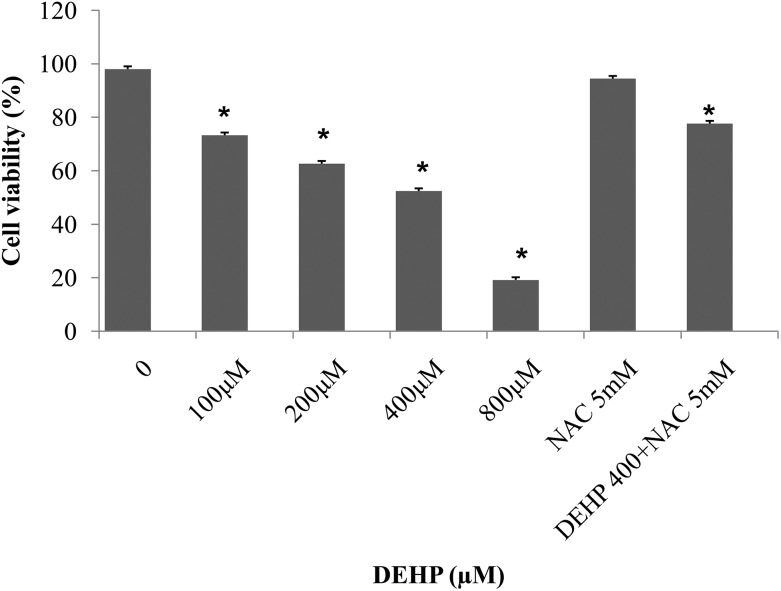

MTT assay

To assess the impact of DEHP exposure on cell viability, an MTT assay was carried out using granulosa cells treated with various concentrations of DEHP (100, 200, 400, and 800 μM) for 72 h. The viability of granulosa cells was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in the treatments with 200, 400 and 800 μM DEHP as compared to the control. In 800 μM DEHP, the cellular viability was less than 20% as compared to the control. However, 400 μM DEHP was the optimal effective concentration to study the effects of DEHP on apoptosis and steroidogenesis in granulosa cells and was used in the following experiments. Further, the combination of DEHP (400 μM) + NAC (5 mM) reduced the DEHP induced cell death (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The representative bar diagram showing the cell viability of granulosa cells after treatment with 0.0, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μM DEHP, NAC (5 mM) and DEHP (400 μM) + NAC (5 mM) for 72 h. Data are obtained from the MTT assay (mean ± SEM) and are normalized with the control group (medium only). Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Significant difference: (*) P < 0.05.

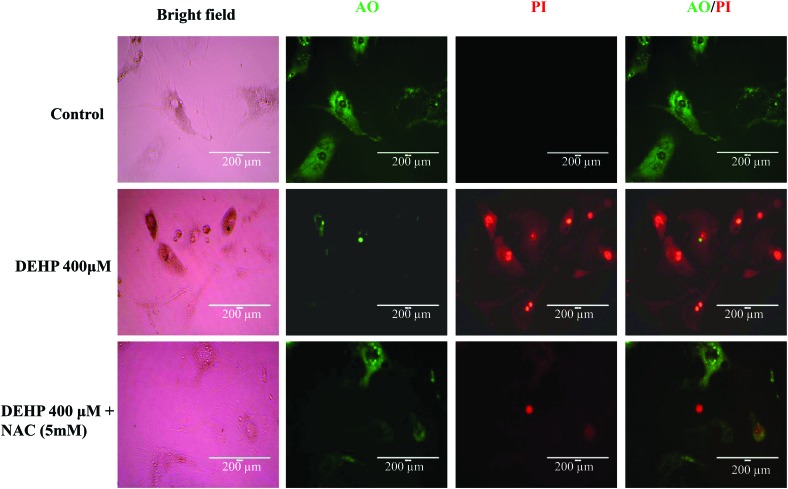

Acridine orange/propidium iodide nuclear staining

As shown in Fig. 2, DEHP (400 μM) induced cellular toxicity in granulosa cells as evidenced by more red fluorescence intensity of nuclear dye propidium iodide (PI) while this effect is protected when granulosa cells were cultured in combination with DEHP (400 μM) + NAC (5 mM) as evident by less red fluorescence intensity of PI staining. Our data suggest that NAC protects the granulosa cells against DEHP induced cellular toxicity.

Fig. 2. Representative photographs showing acridine orange (AO)/propidium iodide (PI) staining for the analysis of cell viability after the control (medium only), DEHP (400 μM) and DEHP + NAC (5 mM) treatment in granulosa cells. DEHP (400 μM) treatment induced morphological apoptotic changes in granulosa cells as evidenced by the increased intensity of PI staining and the reduced intensity of AO staining as compared to the control group. Supplementation of NAC along with DEHP protected granulosa cells against DEHP-induced apoptotic changes as evidenced by the increased intensity of AO staining compared to DEHP alone. Three independent experiments were conducted to confirm the results. (Bar = 200 μm).

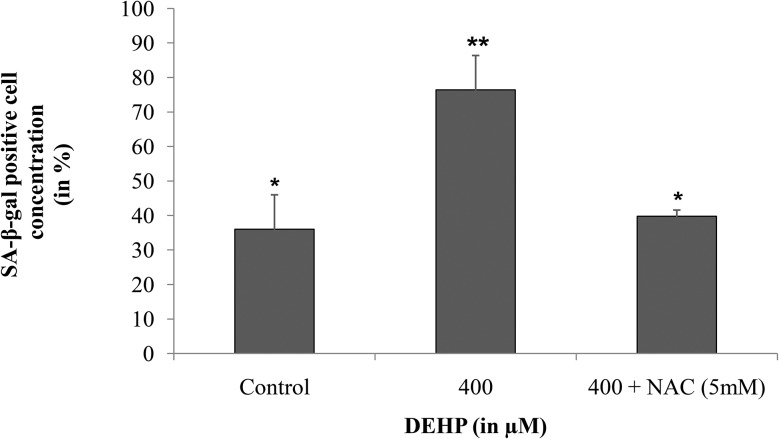

β-Galactosidase assay (SA-β-gal)

Cellular senescence is an event of cell aging, which can be detected by monitoring senescence associated β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-gal). In this study, we performed colorimetric quantitative estimation of β-galactosidase activity in DEHP (400 μM) treated and untreated cells. Higher (p < 0.05) SA-β-gal activity was found in DEHP treated granulosa cells (76.4 ± 9.95%) and in combination of DEHP + NAC (39.8 ± 1.75%) as compared to the control (36.0 ± 9.97%) indicating that DEHP induced cell aging by increasing the SA-β-gal activity (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Effect of DEHP exposure on SA-β-galactosidase activity in granulosa cells. Granulosa cells were exposed in vitro to the control (medium only), DEHP (400 μM) and DEHP + NAC (5 mM) for 72 h and subjected to an enzymatic activity assay for analysis of β-galactosidase activity. DEHP (400 μM) treatment induced cellular senescence in cultured granulosa cells as evidenced by increased β-galactosidase activity as compared to the control and the DEHP + NAC treated group. All values were normalized with the control and the values are shown in percentage. The graph represents means ± SEMs from at least 3 separate experiments. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant p value from the controls at the same time point via ANOVA, post hoc Tukey's HSD (p < 0.05).

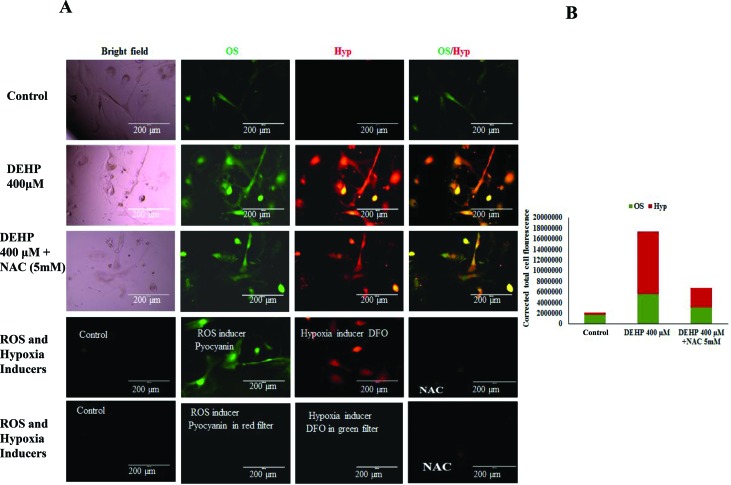

DEHP exposure induced oxidative stress and hypoxic condition

In order to explore whether DEHP induced apoptosis in granulosa cells is mediated by oxidative stress and hypoxia generation, DEHP treated and untreated cells were incubated with a hypoxia/oxidative stress detection mix. As shown in Fig. 4, DEHP (400 μM) treated cells were associated with an increased level of oxidative stress (higher green fluorescence intensity) as well as hypoxia (higher red fluorescence intensity) as compared with the negative control group and the positive control (ROS inducer: pyocyanin and hypoxia inducer: DFO) respectively. Such effects of DEHP were partly abolished by the contemporaneous addition of 5 mM NAC, an antioxidant. A decreased fluorescence intensity was observed in combination with NAC + DEHP as compared to DEHP alone.

Fig. 4. Effect of DEHP (400 μM) on the OS/hypoxia levels in granulosa cells. (A) Granulosa cells were exposed in vitro to DEHP (400 μM) and DEHP + NAC (5 mM) for 72 h and subjected to the OS/hypoxia assay. DEHP (400 μM) treatment induced OS and hypoxia in granulosa cells as evidenced by the increased fluorescence intensity (green and red respectively) as compared to the control. Addition of NAC along with DEHP protected granulosa cells from DEHP-induced OS/hypoxia as evidenced by the decreased intensity of fluorescence as compared to DEHP alone. (B) The fluorescence intensity of OS/hypoxia was compared with a ROS inducer (pyocyanin) and a hypoxia inducer (DFO) for each sample as per the manufacturer's instructions. Three independent experiments were conducted to confirm the results. (Bar = 200 μm).

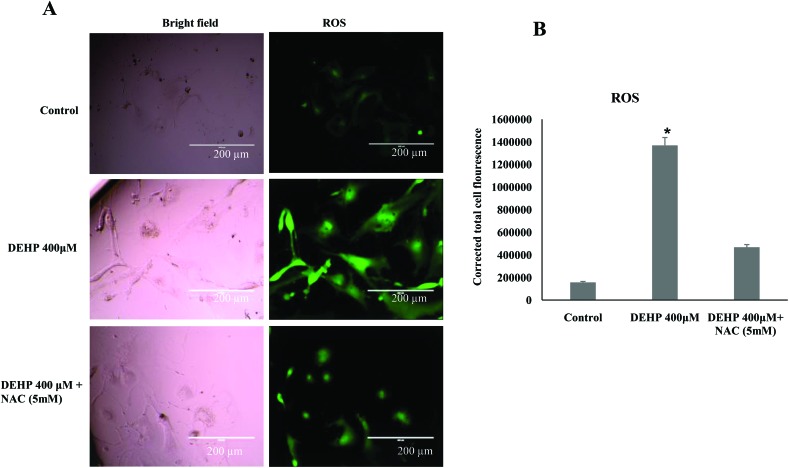

DEHP increased intracellular ROS levels in granulosa cells

Based on the result of oxidative stress, we hypothesized that the treatment of DEHP might have increased the ROS level and thereby apoptosis in granulosa cells. Hence, the intracellular ROS level was analyzed in DEHP treated and untreated cells using a fluorescent probe DCFH-DA. DEHP (400 μM) showed significantly higher values of DCFDA fluorescence intensity, indicative of the intracellular ROS levels, than the control and NAC treated groups (Fig. 5; P < 0.05). Addition of NAC partly reduced the ROS level in DEHP treated granulosa cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Representative photographs showing the intracellular ROS level in DEHP (400 μM) and DEHP + NAC (5 mM) treated granulosa cells. (A) DEHP (400 μM) significantly increased ROS in granulosa cells as evidenced by the increased fluorescence intensity (green) as compared to the control. Treatment of NAC (5 mM) protected granulosa cells against the DEHP-induced increased ROS level in granulosa cells. (B) The bar diagram shows the CTCF analysis of the fluorescence intensity of the control, DEHP and co-treatment of DEHP + NAC. Three independent experiments were conducted to confirm the results. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (Bar = 200 μm).

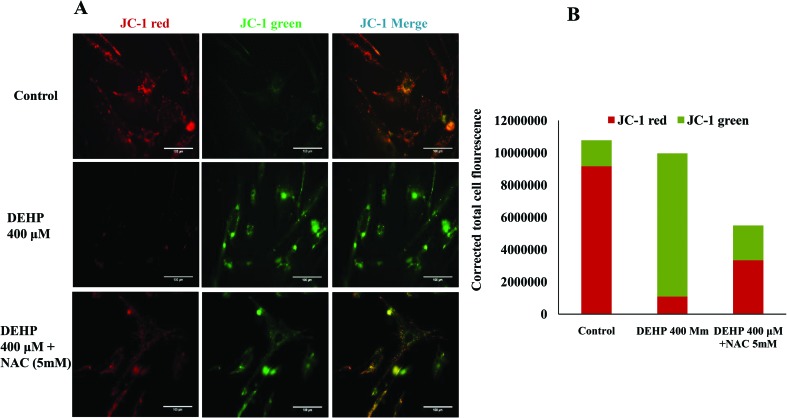

Assessment of the mitochondrial membrane potential

To assess the influence of DEHP induced OS and ROS levels on the mitochondrial membrane potential, we measured mitochondrial activity in DEHP treated and untreated cells. Active mitochondria emit more red fluorescence by readily accumulating JC-1 dye in mitochondria as compared to less active mitochondria that emit green fluorescence and the ratio of red/green fluorescence is indicative of mitochondrial activity in a cell as described earlier.28,29 Our results show that DEHP induced mitochondrial depolarization and increased mitochondria-derived ROS production in granulosa cells in the present study. In addition, we observed that NAC, a ROS scavenger, inhibits the DEHP-induced mitochondrial-ROS production but not to a significant level. As shown in Fig. 6, DEHP (400 μM) induces depolarization of the mitochondria (higher JC1 green florescence) as compared to the control and NAC treated granulosa cells. Our data support the hypothesis that DEHP induces oxidative stress by modulating the mitochondrial membrane potential.

Fig. 6. Representative photographs showing the mitochondrial membrane potential in DEHP (400 μM) and DEHP + NAC (5 mM) treated granulosa cells. (A) DEHP (400 μM) significantly increased mitochondrial depolarization in granulosa cells as evidenced by the increased fluorescence intensity (green) as compared to the control. Treatment of NAC (5 mM) protected granulosa cells against the DEHP-induced mitochondrial membrane potential in granulosa cells. The mitochondrial activity is measured using the mitochondria specific dye JC1. (B) CTCF analysis of the fluorescence intensity of the control, DEHP and co-treatment of DEHP + NAC. Three independent experiments were conducted to confirm the results. (Bar = 100 μm).

DEHP treatment inhibited the secretion of estradiol-17β and progesterone

As shown in Fig. 7, DEHP (400 μM) significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited the production of estradiol-17β and progesterone as compared to the control and NAC treated granulosa cells. However, elevated levels of estradiol and progesterone were observed in the NAC + DEHP treatment group, suggesting that NAC partly abolished the inhibitory action of DEHP on hormone production.

Fig. 7. Effect of DEHP exposure on estradiol and progesterone production. DEHP (400 μM) treatment decreased estradiol and progesterone production in cultured granulosa cells as compared to the control and DEHP + NAC treated group. The graph represents means ± SEMs from at least 3 independent experiments. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant p value from the controls at the same time point via ANOVA, post hoc Tukey's HSD (p < 0.05).

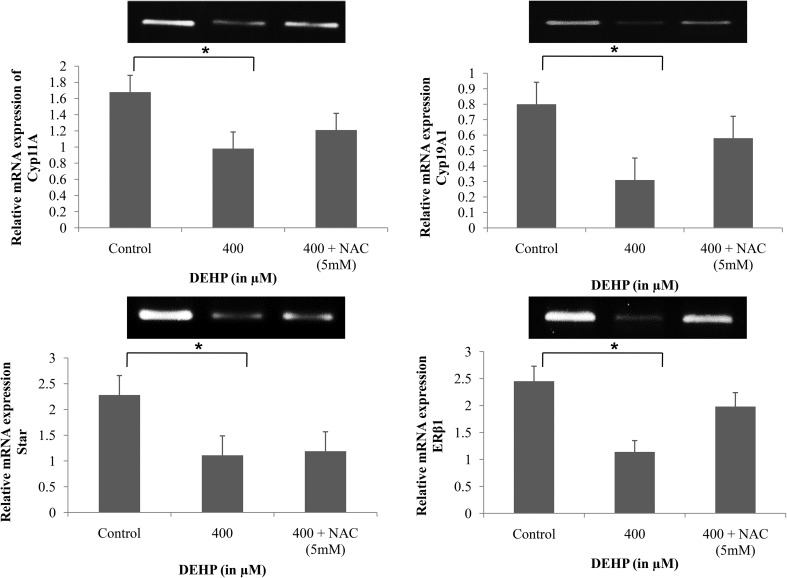

DEHP treatment decreased the expression of steroidogenic genes in granulosa cells

Because DEHP inhibits steroid hormone (estradiol and progesterone) production in cultured granulosa cells, studies were conducted to determine if it did so by altering the expression of steroidogenic responsive genes. The results showed significant down-regulation of steroid responsive genes cyp11A, cyp19A1 and Star in DEHP (400 μM) treated granulosa cells as compared to the control and NAC treated granulosa cells (Fig. 8). The estrogen receptor-β1 (ERβ1) transcript was also found significantly down-regulated in DEHP treated granulosa cells (Fig. 8). The results of down-regulation of steroidogenic genes were reciprocated with low levels of estradiol and progesterone production after DEHP treatment. In all treatment groups, the house keeping gene GAPDH was consistently expressed throughout the culture.

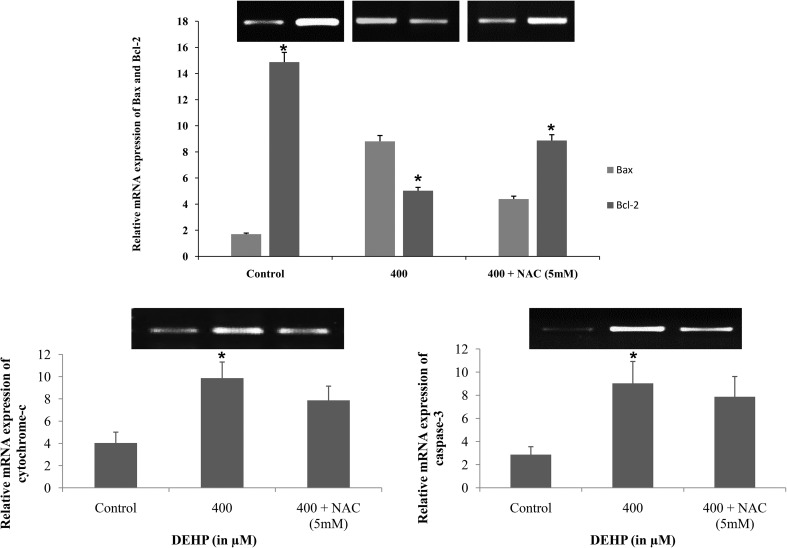

Fig. 8. Representative bar diagram showing the relative mRNA expression level of apoptotic (caspase3 and cytochrome-c) and the ratio of apoptotic and anti-apoptotic (Bax and Bcl2) marker genes in DEHP (400 μM) and DEHP + NAC (5 mM) treated granulosa cells. Treatment of DEHP significantly increased the mRNA expression of Bax, caspase-3 and cytochrome-c and down-regulated the expression of Bcl2 gene in granulosa cells as compared to the control. However, supplementation of NAC along with DEHP rescues the higher expression level of apoptotic genes but not to a significant level as compared to the control. Three independent experiments were conducted to confirm the results. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The number of asterisks as superscripts shows the significant difference (p < 0.05) (control vs. DEHP and NAC + DEHP). The mRNA level was normalized with an endogenous reference of the GAPDH gene.

DEHP treatment increased the expression of pro-apoptotic genes in granulosa cells

We were interested to find out whether DEHP induced morphological apoptotic changes in granulosa cells are associated with the altered expression of apoptotic genes. We performed semi quantitative RT-PCR to evaluate the expression of apoptosis genes in DEHP treated and untreated granulosa cells. The results showed that the mRNA expression of pro-apoptotic genes Bax, cytochrome-c and caspase-3 were significantly (p < 0.05) higher in DEHP (400 μM) treated as compared to the control and NAC treated granulosa cells (Fig. 9). In addition, the mRNA expression of the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl2 was found reduced in DEHP treated cells as compared to the control and NAC treated granulosa cells (Fig. 9). In all treatment groups, the house keeping gene GAPDH was consistently expressed throughout the culture.

Fig. 9. Representative bar diagram showing the relative mRNA expression level of steroid responsive genes (StAR, cyp17a1, cyp19a1 and ERβ1) in DEHP (400 μM) and DEHP + NAC (5 mM) treated granulosa cells. Treatment of DEHP significantly decreased the mRNA expression level of steroid responsive genes in granulosa cells as compared to the control. However, supplementation of NAC along with DEHP rescues the down-regulated expression level of steroid responsive genes. Three independent experiments were conducted to confirm the results. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The number of asterisks as superscripts shows the significant difference (p < 0.05) (control vs. DEHP and NAC + DEHP). The mRNA level was normalized with an endogenous reference of the GAPDH gene.

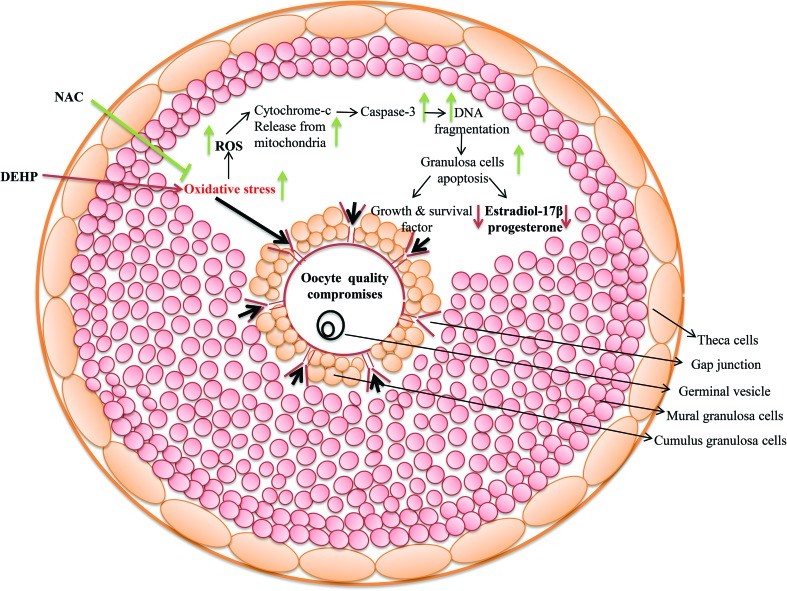

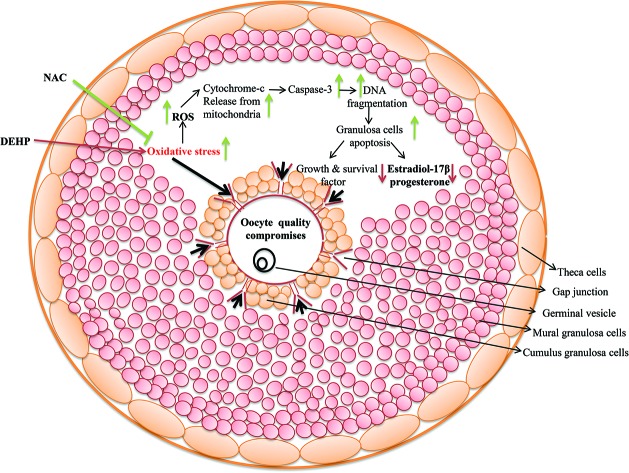

Overall impact of DEHP on steroidogenesis and apoptosis in rat ovarian granulosa cells

Overall, our experimental data revealed that DEHP is toxic to granulosa cells, resulting in their decreasing cellular viability and inducing oxidative stress-ROS-mediated apoptosis. Furthermore, DEHP induced oxidative stress and ROS might play critical roles in modulating the expression of pro-apoptotic (Bax, cytochrome c and caspase-3) and steroidogenic responsive genes in granulosa cells (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. A schematic diagram showing the possible mechanism of DEHP action on ovarian granulosa cells. DEHP induces oxidative stress (OS) by generation of ROS and thereby granulosa cell apoptosis via DNA fragmentation and a higher expression of apoptotic genes. The increased level of ROS leads to the disruption of cell communication and reduction of estradiol and progesterone production by modulating the steroid responsive gene expression. As a result, granulosa cell apoptosis deteriorates oocyte quality and directly affects fertilization as well as the pregnancy rate resulting in a poor reproductive health outcome.

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate whether DEHP-induced OS affects the quality of oocytes by inducing apoptosis and hampering steroidogenesis in granulosa cells. Our main findings indicated that DEHP exposure induced OS and ROS production and thereby increased the expression of pro-apoptotic genes and also modulated steroidogenic responsive genes in granulosa cells resulting in inhibited steroid production. In animal experiments, DEHP has been evaluated for developmental and reproductive toxicity for several decades. Most of the studies were focused on DEHP exposure via inhalation, ingestion or oral administration wherein only a vague concentration reaches the target organ or the associated area. However, no such in vitro studies have been conducted using ovarian granulosa cells to examine whether the in vitro treatment of DEHP induces the generation of ROS and if so, whether DEHP-induced apoptosis is mediated through the mitochondrial pathway as a result of disrupted ovarian steroidogenesis. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the cytotoxicity and the genotoxic potential of DEHP and its metabolites decreased the cell viability and steroidogenic potential in various animal models including humans. Recently it has been shown that prenatal exposure to DEHP has multigenerational and transgenerational effects on female reproduction and it may accelerate reproductive aging.20,21 Further, few reports have provided evidence for a negative association between the urinary concentrations of certain phthalate metabolites and serum INHB levels,9,10 suggesting an adverse effect of phthalate exposure on growing human antral follicles. It has also shown that the exposure of phthalate is associated with the alterations of reproductive hormone levels in girls.9 In an in vitro study it is demonstrated that DEHP affects oocyte maturation and the embryogenesis process.17 Further, it is reported that the addition of MEHP, during bovine oocyte in vitro maturation, inhibits meiotic maturation in a dose-dependent manner.31 This result was further confirmed in a subsequent study performed in mouse oocytes,32 where no effect was noticed by adding DEHP in an IVM culture of pig oocytes. In this study, we have conducted an MTT assay to determine the optimum effective dose of DEHP on granulosa cells and found that 400 μM DEHP was the optimum effective dose that exerted a negative effect via increasing the OS and intracellular ROS level which ultimately caused apoptosis in granulosa cells. Although it is now clear that DEHP exerts negative effects on the female reproductive system, their effects on female germ cell physiology still remains poorly understood.

Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between pro-oxidant and antioxidants, which results in damage to cellular components including proteins, lipids and DNA.30 Induction of oxidative stress leads to the generation of ROS which have both physiological and pathological roles during various reproductive functions.33 Several studies have shown that oxidative stress is directly associated with cellular aging23,34–39 and low success rates in assistant reproductive techniques.35 It has been shown that the oral administration of DEHP in rats increased the generation of ROS such as the superoxide radical and H2O2.34 Further, it is also demonstrated that DEHP alters the expression of antioxidant enzymes and induces oxidative stress in the male reproductive system.40–42 MEHP, an active metabolite of DEHP is also reported to selectively induce oxidative stress and is responsible for the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, thereby inducing apoptosis in germ cells.34 Recently, in a study it is reported that the exposure of benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP), a widespread EDC, increased adipogenesis and metabolic dysregulation via impairing vital epigenetic regulators.43 This study shows that the exposure of DEHP increases the OS, ROS and β-galactosidase levels in granulosa cells as compared to control cells. This result indicates that the exposure of DEHP causes an increase in superoxide radicals in the granulosa cells, which further induces oxidative stress and ROS production and thereby causes DNA damage in cultured granulosa cells.

In this study, we have demonstrated that DEHP (400 μg ml–1) increases the ROS level, the expression of pro-apoptotic genes (Bax, cytochrome-c and caspase-3) and decreases the expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 gene in cultured granulosa cells. In addition, we have found that co-treatment with NAC, a known antioxidant, rescues the granulosa cells from DEHP-induced ROS generation and restores the expression of the Bcl2 gene. It is reported that DEHP even at lower concentrations (50–100 μM) alters the gene expression profiles, which suggests that little exposure of DEHP may alter the expression of important developmental genes.44 Further, it is reported that NAC acts as a free radical scavenger and glutathione precursor in reproductive and non-reproductive tissues and protects them from oxidative stress induced apoptosis.45–47 However, the mechanism by which NAC works to prevent DEHP-induced toxicity is not known. In this study, we have shown that supplementation of NAC along with DEHP rescues the effects of DEHP on the OS, ROS, β-galactosidase levels and gene expression activities but not to a significant level. Altogether, these results suggest that NAC acts as a ROS scavenger and at least partially rescues the DEHP induced toxicity in ovarian granulosa cells. In another experiment, we have found an increased level of β-galactosidase, which is an indicator of cellular aging, in DEHP (400 μg ml–1) treated granulosa cells compared to the control, which suggests that DEHP increased cell aging through increasing β-galactosidase activity. These two sets of data suggest that DEHP might work through the mitochondrial oxidative stress pathway which induces ROS generation and thereby a higher expression of pro-apoptotic genes, which leads to apoptosis in ovarian granulosa cells. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that DEHP induces oxidative stress and ROS production by disrupting the expression of anti- and pro-apoptotic genes in ovarian granulosa cells.

Mammalian ovaries perform two important processes like folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis which are essential for maintenance of an appropriately timed reproductive cycle, senescence and fertility. It has been shown that DEHP represses granulosa cell estradiol production with consequent alterations of the gonadal–hypothalamic feedback, modifications of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels.48 It is also demonstrated that in-utero and lactational DEHP exposure alters estrogen synthesis via dysregulation of the pituitary–gonadal feedback and impairs the reproductive performance of exposed animals.45–49 It is demonstrated that DEHP inhibits follicle growth by inducing the production of ROS and by decreasing the expression and activity of SOD1. We have also shown that DEHP treatment decreases the expression and activity of steroid responsive genes (cyp11A, cyp19A1 and Star) and the effect of DEHP was normalized by supplementation of NAC. Thus, it is quite possible that DEHP-induced oxidative stress alters the activity of steroid responsive genes as a result of inhibition of steroid synthesis while NAC prevents these processes. It is believed that DEHP may induce its toxicity in two ways; either by disturbing the levels of some hormones like estrogen or progesterone, thus reducing fertility or probably by inducing oxidative stress via ROS generation, hence leading to granulosa cell apoptosis.

Conclusion

On the basis of our research findings and available literature, it is logical to state that DEHP might be one of the factors that are responsible for early puberty, disturbance in the menstrual cycle, amenorrhea, and recurrent abortion. It can be argued that reproductive health is one of the most prevalent health care problems in India especially in rural areas because of the lack of adequate primary healthcare facilities, unhygienic conditions and direct exposure to various kinds of endocrine disruptors. In conclusion, this study revealed that DEHP causes oxidative stress via ROS production and inhibition of steroid synthesis via modulation of steroidogenic responsive genes in granulosa cells that finally lead to the induction of apoptosis through the activation of Bax/Bcl-2-cytochrome-c and the caspase3-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Further, molecular studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of DEHP on the reproductive health of humans considering the substantial use of plastic products for wider applications. In addition, we should reduce environmental exposure of DEHP and spread awareness among women to protect against DEHP-induced reproductive toxicity.

Author contributions

Dr Pawan Dubey and Dr Anima Tripathi wrote the manuscript and Vivek Pandey performed most of the in vitro studies. Dr Alok Singh was involved in in vitro experiments. Dr AN Sahu corrected the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Science and Engineering Research Board, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India (Grant No. SERB/YS/000819).

References

- Bauer M., Herrmann R. Sci. Total Environ. 1997;208:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(97)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambia K., Dine T., Gressier B., Dupin-Spriet T., Luyckx M., Brunet C. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2004;27:971–978. doi: 10.1177/039139880402701110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson J., De Korte D. Transfus. Med. 2011;21:73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2010.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. F., Zhang L. J., Li L., Feng Y. N., Chen B., Ma J. M., Huynh E., Shi Q. H., De Felici M., Shen W. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2013;54:354–361. doi: 10.1002/em.21776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Li L., Qin X. S., Zhou Y., Zhang X. F., Wang L. Q., De Felici M., Chen H., Qin G. Q., Shen W. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2014;55:343–353. doi: 10.1002/em.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boberg J., Christiansen S., Axelstad M., Kledal T. S., Vinggaard A. M., Dalgaard M., Nellemann C., Hass U. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011;31:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James-Todd T. M., Meeker J. D., Huang T., Hauser R., Ferguson K. K., Rich-Edwards J. W., McElrath T. F., Seely E. W. Environ. Int. 2016;96:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon P. R., Niermann S., Flaws J. A. Toxicol. Sci. 2015;150:97–108. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H.-J., Chen C.-C., Wu M.-T., Chen M.-L., Sun C.-W., Wu W.-C., Huang I.-W., Huang P.-C., Yu T.-Y., Hsiung C. A. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y.-Y., Guo N., Wang Y.-X., Hua X., Deng T.-R., Teng X.-M., Yao Y.-C., Li Y.-F. Reprod. Health. 2018;15:33. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0469-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P.-C., Kuo P.-L., Chou Y.-Y., Lin S.-J., Lee C.-C. Environ. Int. 2009;35:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Högberg J., Hanberg A., Berglund M., Skerfving S., Remberger M., Calafat A. M., Filipsson A. F., Jansson B., Johansson N., Appelgren M. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;116:334–339. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krotz S. P., Carson S. A., Tomey C., Buster J. E. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2012;29:773–777. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. L., Bose H. S. J. Lipid Res. 2011;52:2111–2135. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R016675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FITZPATRICK S. L., Richards J. S. Endocrinology. 1991;129:1452–1462. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-3-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghersevich S., Poutanen M., Tapanainen J., Vihko R. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1963–1971. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7956918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambruosi B., Uranio M. F., Sardanelli A. M., Pocar P., Martino N. A., Paternoster M. S., Amati F., Dell'Aquila M. E. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Liu J.-C., Lai F.-N., Liu H.-Q., Zhang X.-F., Dyce P. W., Shen W., Chen H. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-C., Lai F.-N., Li L., Sun X.-F., Cheng S.-F., Ge W., Wang Y.-F., Li L., Zhang X.-F., De Felici M. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2966. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm E., Rattan S., Gao L., Flaws J. A. Endocrinology. 2017;159:795–809. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-03004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan S., Brehm E., Gao L., Flaws J. A. Toxicol. Sci. 2018;163:420–429. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu G., Dai J., Zhang D., Zhu L., Tang X., Zhang L., Zhou T., Duan P., Quan C., Zhang Z. Environ. Toxicol. 2017;32:1055–1064. doi: 10.1002/tox.22304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A., Allamaneni S. S., Nallella K. P., George A. T., Mascha E. Fertil. Steril. 2005;84:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A., Chaube S. K. Apoptosis. 2012;17:439–448. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0702-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K., Miller K. P., Babus J. K., Flaws J. A. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;93:382–389. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Liu Y., An Z., Huang D., Qi Y., Zhang Y. Toxicol. in Vitro. 2011;25:979–984. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peropadre A., Fernández F. P., Herrero O., Perez Martin J. M., Hazen M. J. Curr. Top. Toxicol. 2013;9:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Peropadre A., Paloma F. F., Perez Martin J. M., Herrero O., Hazen M. J. Toxicol. in Vitro. 2015;30:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry W. L., Hemstreet III G. P. J. Urol. 1988;139:270–274. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey P. K., Tripathi V., Singh R. P., Saikumar G., Katiyar A. N., Pratheesh M. D., Gade N., Sharma G. T. Theriogenology. 2012;77:280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anas M.-K. I., Suzuki C., Yoshioka K., Iwamura S. Reprod. Toxicol. 2003;17:305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(03)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalman A., Eimani H., Sepehri H., Ashtiani S., Valojerdi M., Eftekhari-Yazdi P., Shahverdi A. BioFactors. 2008;33:149–155. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520330207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M., Leibfritz D., Moncol J., Cronin M. T., Mazur M., Telser J. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A., Gupta S., Sekhon L., Shah R. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2008;10:1375–1404. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn H. J., Sohn I. P., Kwon H. C., Jo D. H., Park Y. D., Min C. K. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2002;61:466–476. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Blerkom J., Davis P., Alexander S. Hum. Reprod. 2003;18:2429–2440. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suna S., Yamaguchi F., Kimura S., Tokuda M., Jitsunari F. Toxicol. Lett. 2007;173:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatone C., Amicarelli F., Carbone M. C., Monteleone P., Caserta D., Marci R., Artini P. G., Piomboni P., Focarelli R. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2008;14:131–142. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A., PremKumar K. V., Pandey A. N., Khatun S., Mishra S. K., Shrivastav T. G., Chaube S. K. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;667:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos L., Stevenson D., Gomes F., Silva-Carvalho J., Almeida H. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2009;15:411–419. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botelho G. G., Bufalo A. C., Boareto A. C., Muller J. C., Morais R. N., Martino-Andrade A. J., Lemos K. R., Dalsenter P. R. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009;57:785–793. doi: 10.1007/s00244-009-9385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkekoglu P., Rachidi W., Yuzugullu O. G., Giray B., Favier A., Ozturk M., Hincal F. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;248:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Choudhury M. Toxicol. in Vitro. 2017;39:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokanson R., Hanneman W., Hennessey M., Donnelly K. C., McDonald T., Chowdhary R., Busbee D. L. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2006;25:687–695. doi: 10.1177/0960327106071977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkkila K., Hirvonen V., Wuokko E., Parvinen M., Dunkel L. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:2523–2531. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otala M., Erkkilä K., Tuuri T., Sjöberg J., Suomalainen L., Suikkari A. M., Pentikäinen V., Dunkel L. MHR: Basic Sci. Reprod. Med. 2002;8:228–236. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya S., Vijayalakshmi P., Vivekanandan P., Karthikeyan S. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2011;27:914–922. doi: 10.1177/0748233711399323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B., Weaver R., Gaines L., Heindel J. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1994;128:224–228. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocar P., Fiandanese N., Secchi C., Berrini A., Fischer B., Schmidt J. S., Schaedlich K., Borromeo V. Endocrinology. 2012;153:937–948. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]