Abstract

Comprehensive renal biopsy evaluation of canine glomerular disease uses immunofluorescence (IF) labeling of fresh frozen tissue to detect immune complexes that are confirmed with transmission electron microscopy. This methodology requires the veterinarian to harvest additional tissue samples, whereas sections for immunohistochemistry (IHC) could be performed on paraffin sections. If adequate IHC labeling of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was possible, the additional tissue samples would be unnecessary. We compared the specificity and sensitivity of IHC to IF for diagnosis of immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis (ICGN). Commercial anti-canine IHC and IF antibodies targeting the lambda light chain component of immunoglobulins were evaluated, using previously diagnosed cases of ICGN and cases without immune complexes (non-ICGN). Because the pattern of IF labeling is crucial for accurate interpretation, sections were evaluated by a trained nephropathologist and a novice to assess the impact of experience in the diagnosis of ICGN. Unfortunately, our attempts to develop an IHC protocol that could improve the workflow for clinicians and laboratory personnel were unsuccessful; the IHC protocol did not demonstrate staining patterns that could be detected reliably by either evaluator. Moreover, the IHC antibody demonstrated abundant nonspecific staining in non-ICGN cases, and 60% of true ICGN cases were misdiagnosed as non-ICGN. We did not achieve a reliable IHC protocol for the anti-lambda light chain antibody and, therefore, IF for lambda light chain remains the method of choice for ICGN detection.

Keywords: Glomerulopathy, immune complex, immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry, transmission electron microscopy

Glomerulopathies can be caused by deposition of immune complexes (IC) along the glomerular basement membrane (as a result of either exogenous or endogenous antigens) or from diseases that do not involve IC deposition. The diagnosis of IC-mediated glomerulonephritis (ICGN) with light microscopy alone can be difficult because non-ICGN diseases can have histologic lesions that resemble IC deposition. Differentiation of ICGN from non-ICGN disease is vital in the guidance of treatment decisions and has prognostic implications. In a 2013 paper estimating the prevalence of ICGN in proteinuric North American dogs, ~50% of submitted canine renal biopsies did not have ICGN.12 Incorrect diagnosis exposes these patients to unnecessary risks associated with immunosuppressive therapy as well as increased treatment costs. Hence, advanced and accurate diagnostic tests are critical tools to facilitate and establish a correct diagnosis. In human medicine, routine renal biopsy evaluation includes immunofluorescence (IF) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for the identification of ICs.16 Since 2008, the International Veterinary Renal Pathology Service (IVRPS, https://vet.osu.edu/vmc/international-veterinary-renal-pathology-service-ivrps) routinely performs IF and TEM in addition to light microscopy for the diagnosis of ICGN in small animals.3,4 In addition to merely detecting positive labeling, IF evaluation involves assessment of staining patterns (i.e., granular vs. splotchy vs. linear) and IC distribution within the glomerulus (glomerular capillary walls and/or mesangium). This assessment requires sufficient training and experience and is enhanced when TEM is performed concurrently to demonstrate the presence or lack of electron-dense deposits, which are suggestive of IC.13

These advanced modalities (IF and TEM) necessitate additional processing steps and specialized equipment (e.g., an epifluorescence or confocal microscope, and a transmission electron microscope). They also require the harvest of extra tissue specimens and placement into separate media or fixatives. For submission to the IVRPS, clinicians are asked to place portions of the biopsy in Michel transport medium, a buffer, because IF cannot be performed on formalin-fixed tissue. If a reliable immunohistochemistry (IHC) protocol can be optimized, clinicians would only need to submit a formalin-fixed sample and the extra sample processing steps would be minimized. This might also mean that evaluation for ICGN could be performed in a diagnostic laboratory by a general pathologist without the requirement of a fluorescence microscope.

Previous literature has reported the use of IHC in diagnosis of ICGN in dogs,5,6,8–11 but there are no studies to demonstrate whether IHC on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue exhibits results similar to IF. In fact, to our knowledge, the reliability of IHC in detecting ICGN in dogs is currently unknown. We therefore evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of IHC compared to IF in differentiating ICGN from non-ICGN cases. Importantly, the optimized IHC protocol would need to be a practical and efficient tool for routine use in a veterinary diagnostic renal biopsy service. Lambda light chain (LLC) was chosen as the antigen of interest because it is present in almost all canine immunoglobulins,1 and should detect all types of IC regardless of the heavy-chain component. In our experience, LLC is easily detectable with IF in ICGN cases and is absent in non-ICGN cases.3 The antibody we chose has previously been demonstrated by ELISA to detect canine LLC.14

Our hypothesis was that an optimized IHC protocol would allow evaluators to detect immune deposition and distinguish ICGN from non-ICGN cases with consistency similar to IF. Because pattern and location of staining is crucial in the diagnosis of ICGN in IF evaluation, we also hypothesized that IHC would permit a trained nephropathologist to reliably distinguish ICGN from non-ICGN cases, whereas a general (novice) pathologist might base the score on intensity. As such, we predicted that the inter-scorer agreement (trained vs. novice) would be low.

In a pilot study to test various IHC staining conditions, 3 representative cases of each of the following glomerular diseases were selected: membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN), membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). Of note, both MGN and MPGN are subcategories of ICGN. FSGS is an example of a disease that does not involve ICs (non-ICGN). Samples for histology were fixed and submitted to the IVRPS in 10% formalin solution prior to routine processing and paraffin embedding. Tissue specimens were serially sectioned, and a routine panel of special stains (periodic acid–Schiff [PAS], Masson trichrome, and Jones methenamine silver) had been performed for histologic evaluation. Samples submitted for IF and TEM (in Michel transport medium and 3% glutaraldehyde, respectively) were processed as described previously.2,3 All diagnoses had been rendered by a single board-certified veterinary anatomic pathologist with expertise in nephropathology (RE Cianciolo).

For the IHC pilot study, FFPE tissues were sectioned at 4-μm thickness, and slides were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated with distilled water prior to staining. Indirect IHC was performed using a goat anti-canine LLC primary antibody (A40-124A, Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) with a biotinylated rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Primary antibody was diluted in primary antibody diluent with background-reducing components (Dako North America, Santa Clara, CA), and secondary antibodies were diluted to 1:200 in serum-free protein block (Dako). Tissues were stained using an autostainer (Autostainer 360, Thermo Scientific, Grand Island, NY). The staining protocol is described as follows: rehydration of the slides was followed by 10-min serum-free protein block (Dako) and primary antibody incubation for 1 h. Several antibody dilutions were used both with and without antigen retrieval (Table 1). Slides were then incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min followed by 30-min incubation with peroxidase reagent (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC HRP reagent, Vector Laboratories) and incubation with the chromogen for 5 min (Liquid DAB and substrate chromogen system, Dako). For samples that underwent antigen retrieval, FFPE tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated with target retrieval solution (Dako). Slides were transferred to a pressure cooker and heated to 125°C and cooled to 90°C for 10 s. Slides were rinsed with distilled water and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min prior to IHC staining. Following completion of the staining procedure, tissue specimens were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Table 1.

Summary of immunohistochemical optimization of goat anti-canine lambda light chain (A40-124A, Bethyl Laboratories) in immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis (ICGN) and non-ICGN cases in the pilot study.

| IHC protocol/Dilution | Target retrieval | Staining pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect antibody with secondary antibody | ||

| 1:100; 1:200; 1:500 | Yes | Entire specimen stained; specific staining of any structure could not be identified |

| 1:500; 1:1,000 | No | Glomerular capillary walls often stained positively; variable staining of interstitium; frequent staining of podocytes and material in capillary lumens (presumed plasma) |

IHC = immunohistochemistry.

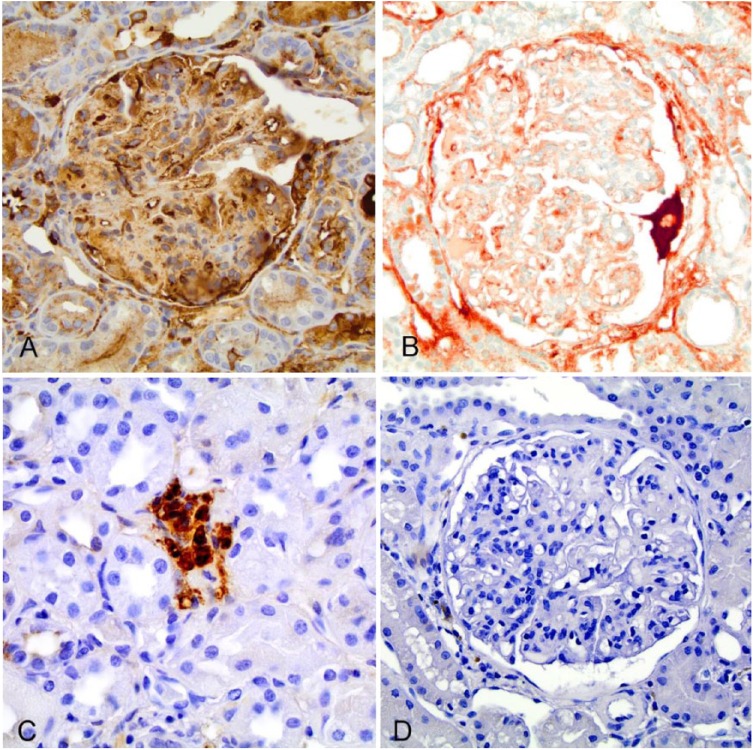

The protocol using antigen retrieval demonstrated abundant nonspecific staining of interstitial cells, capillary lumens, glomerular capillary loops, and cytoplasm of podocytes, parietal cells, and tubular epithelial cells at all dilutions (1:100, 1:200, and 1:500; Table 1; Fig. 1A). Without antigen retrieval, there was reduced background staining, but there appeared to be nonspecific labeling of the interstitium at these dilutions (Fig. 1B). Specifically, there was preferential labeling of glomeruli with sparser staining of the tubulointerstitium in many of the samples. However, the highest dilution (1:1,000) allowed interpretation of glomerular staining with limited background staining. Staining of mononuclear inflammatory cells in the interstitium suggests affinity of the antibody for LLC in plasma cells (Fig. 1C). To assess whether the secondary antibody was contributing to nonspecific staining, tissue specimens were stained alone with a 1:200 dilution of secondary antibody and did not show nonspecific staining of renal tissue (Fig. 1D). Based on these initial results, IHC using the anti-canine LLC antibody at 1:1,000 without antigen retrieval was considered to be a relatively better condition to test additional cases.

Figure 1.

Canine renal tissues labeled with anti-canine lambda light chain (LLC) antibody (A40-124A, Bethyl Laboratories) and counterstained with hematoxylin. All images were captured at 40× magnification. A. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of an immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis (ICGN) case stained with anti-canine LLC antibody at 1:500 dilution with antigen retrieval shows nonspecific staining of the glomerulus. B. IHC of the same ICGN case stained with anti-canine LLC antibody at 1:500 dilution without target retrieval reduced the background staining. C. IHC of a focal segmental glomerulosclerosis case stained with anti-canine LLC antibody at 1:1,000 dilution demonstrates staining of plasma cells. D. IHC of an ICGN case stained with biotinylated rabbit anti-goat antibody at a 1:200 dilution does not exhibit nonspecific staining of the glomerulus.

After completion of the pilot study, 40 additional canine kidney specimens (20 ICGN, 20 FSGS) were selected from previously diagnosed cases from the IVRPS. All cases were submitted to the IVRPS within the previous year and had undergone comprehensive evaluation with histology, TEM, and IF. Three FSGS cases were excluded from the study because of lack of glomeruli in the deeper levels of the FFPE tissue blocks. Therefore, IHC using the anti-canine LLC antibody was tested on 37 specimens, which consisted of 20 ICGN and 17 FSGS cases.

After staining the 37 cases, tissue sections were evaluated by a novice scorer and a trained nephropathologist. The novice scorer (A Wong) had general experience in IHC staining and slide evaluation but did not have specific nephropathology training. The trained scorer (RE Cianciolo) had years of experience in the evaluation of IF renal biopsy samples from small animals and humans. The scorers were blinded to the previous IF and TEM results. A numerical value of 0–3 was assigned corresponding to the immunolabeling intensity of the glomerular structures with a score of 0 = no stain, 1 = weak staining, 2 = moderate, and 3 = most intense stain. Staining pattern (i.e., granular, linear, splotchy) was noted.4,15 Granular patterns were defined as discrete small dots along capillary walls; linear patterns were defined as positive labeling outlining capillary walls with a smooth contour; splotchy was defined as large lakes of positive staining. The scorers focused their evaluation on the glomerular capillary walls, capillary lumens, mesangium, and podocyte cytoplasm, but also noted which non-glomerular structures and cells were stained positively.

After examining the cases, both scorers agreed that there was a wide variety of staining patterns even within a single tissue sample. Moreover, the pattern could not be categorized easily when the intensity score was ⩾2. Given the inability to assign a pattern to a case, the intensity score alone was used to place a case into categories of ICGN and non-ICGN. Cases with an intensity score of ⩾2 were categorized as “potential ICGN” and <2 were categorized as “non-ICGN.” Sensitivity and specificity were calculated from the IHC results obtained from the novice and trained scores. The IHC results were compared to the gold standard results from IF and TEM. WinEpi (http://www.winepi.net/uk/index.htm) was used to calculate the confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity. A kappa statistic was used to measure inter-rater agreement.15

When using IHC to distinguish ICGN from non-ICGN in the 37 specimens, 82% of FSGS cases were incorrectly diagnosed as ICGN (false positives), and 60% of the true ICGN cases were misdiagnosed as non-ICGN (false negatives) by the expert scorer (Table 2). The novice scorer reported 76% of FSGS as ICGN (false positives) and 65% of true ICGN cases as FSGS (false negatives). Overall, the observed agreement of the scorers was 89% with a kappa statistic of 0.78, which constitutes “substantial” agreement between the observers.15 The observers disagreed on 4 cases, and the discrepancy rested on the subjective interpretation of the level of intensity of the stained tissue specimen. Overall, the results indicate that even though there was inter-observer agreement, diagnosis based on IHC performed poorly compared to the gold standard of IF when using anti-LLC antibodies. Comprehensive results for all 37 specimens (light microscopy, IF, TEM, and IHC results) are included in supplemental materials (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of anti-canine lambda light chain antibody for diagnosis of immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|

| Expert | 40% (18.5%, 61.5%) | 17.6% (−0.5%, 35.8%) |

| Novice | 35% (14.1%, 55.9%) | 23.5% (3.4%, 43.7%) |

Numbers in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

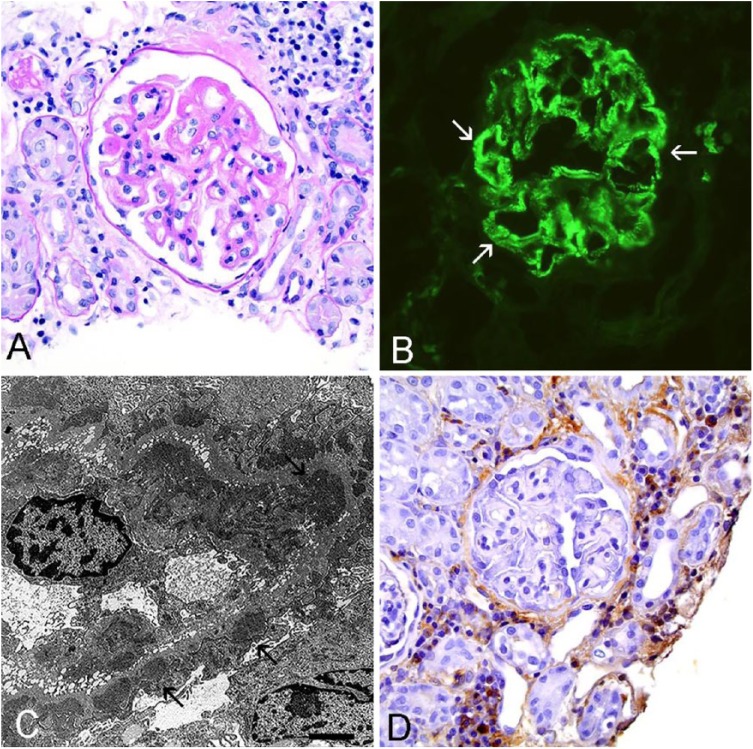

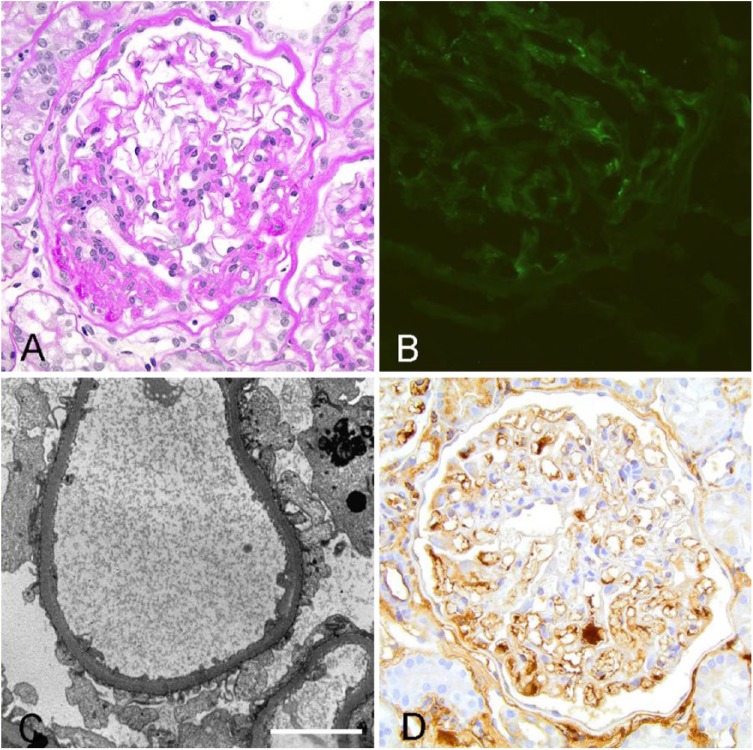

When comparing the quality of IHC to IF and TEM in an ICGN case, IHC failed to demonstrate similar staining patterns compared to the current IF and TEM protocol (Figs. 2, 3). In an ICGN case, PAS–hematoxylin (PASH) stain demonstrates thickening and remodeling of the capillary walls (Fig. 2A). The fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-LLC antibody shows discrete granular staining along the glomerular capillary walls and mesangium (Fig. 2B). IC deposition was confirmed with TEM demonstration of subendothelial and subepithelial electron-dense deposits along the capillary wall (Fig. 2C). IHC of the same case shows faint brown staining along a few capillary walls and was scored as a 1, and discrete granularity of the stain was not discernible (Fig. 2D). There was also intense IHC staining in the interstitium, which is a location that was negative on IF evaluation and did not have electron-dense deposits identified on TEM. Similarly, IHC staining of a non-ICGN case exhibited nonspecific binding with the IHC antibody (Fig. 3). Light microscopy with PASH showed segmental glomerulosclerosis (Fig. 3A), and the IF evaluation did not demonstrate any specific staining pattern consistent with ICs (Fig. 3B). Electron microscopy did not exhibit electron-dense deposits along the capillary walls (Fig. 3C), but the IHC antibody labeled multiple structures including intense staining of the glomerular capillary walls and mesangium as well as tubular interstitium and tubular epithelium (Fig. 3D).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) with anti-canine lambda light chain (LLC) antibody (A40-124A, Bethyl Laboratories) in an immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis (ICGN) case failed to demonstrate similar staining patterns compared to immunofluorescence (IF) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). All images were captured at 40× magnification. A. Periodic acid-Schiff–hematoxylin stain of an ICGN case demonstrates glomerular basement membrane remodeling. B. The same ICGN case shows granular staining (arrows) along the capillary walls using the current IF protocol. C. TEM of the same case demonstrates electron-dense deposits consistent with immune complexes (arrows) along the capillary wall. Bar = 2 µm. D. IHC with the anti-canine LLC antibody (1:1,000) shows very faint staining of capillary walls but intense staining of the interstitium.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of a non–immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis case exhibits nonspecific labeling of the glomerular basement membrane. All images were captured at 40× magnification. A. Light microscopy with periodic acid-Schiff–hematoxylin stain shows segmental glomerulosclerosis. B. Immunofluorescence does not demonstrate immune complexes along the glomerular basement membrane. C. Transmission electron microscopy of the same case does not exhibit electron-dense deposits along capillary walls. Bar = 5 µm. D. IHC with the anti-canine lambda light chain antibody (A40-124A, Bethyl Laboratories; 1:1,000) shows staining of multiple structures including intense staining of the tubular interstitium, tubular epithelium, areas in the mesangium, and capillary walls.

Veterinary nephropathologists at the IVRPS identify IC in capillary walls using a panel of FITC-labeled antibodies targeting Ig heavy chains (gamma, mu, and alpha), light chains (lambda and kappa), and complement factors (C3 and C1q). We examined anti-LLC antibodies because the FITC-labeled LLC is the most robust stain of the IF panel. Moreover, it is expected that these anti-LLC antibodies should label any immunoglobulins present within the capillary walls, irrespective of the type of heavy chain in the complexes.1

Although LLC within plasma cells reacted positive by IHC, the inability of IHC to reliably detect IC within tissues compared to IF could be attributed to the lack of available epitopes after tissue fixation and processing. Formalin fixation can alter the 3-dimensional structure of the epitope, or cross-link proteins and prevent antibody detection.7 In comparison, IF is evaluated on unfixed, frozen tissue. Because one goal of our study was to develop a labeling method that could be used on the same FFPE tissue used for light microscopy, simply performing IHC on fresh frozen tissue would still require harvest of additional kidney samples, which does not improve the current workflow.

The poor performance of the IHC LLC antibody might also be attributed to the enzymatic reporter system conjugated to the antibody. The IHC antibody is conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP), which is a larger molecule (44 kDa) than the FITC fluorophore that is conjugated to the IF antibody. The conjugated HRP molecule can reduce the accessibility of the antibody to the targeted antigen.2 It is possible that a direct IHC protocol for LLC might be more successful. Polymer-based secondary antibody detection systems could also be employed to enhance sensitivity; however, polymers might result in an aggregated chromogen signal that could obscure the pathologist’s ability to detect a granular staining pattern. Other types of antigen detection protocols (e.g., microwave) could also be employed for IHC optimization; however, given that antigen retrieval using a pressure cooker resulted in diffuse nonspecific strong labeling, we did not attempt additional methods of antigen retrieval.

All glomerular structures were intensely stained with the anti-canine LLC antibody in the majority of FSGS cases. Nonspecific binding of antibodies can be attributed to numerous causes including length of fixation of the tissue specimen, low affinity of the antibody, or nonspecific detection of endogenous sources of peroxide.2,7 In our study, the length of tissue fixation is an unlikely reason for the staining discrepancy observed between ICGN and FSGS cases because tissue specimens were routinely processed within 24–72 h after the biopsy. Secondary antibodies can also contribute to nonspecific staining and have previously been shown to bind nonspecifically to epitopes exposed in damaged tissue.7 This explanation is also unlikely because several slides were stained only with secondary antibody (negative control tissue) and nonspecific staining was not observed in these negative control tissue specimens (Fig. 1D). Regardless of the cause of nonspecific staining, IHC using the anti-canine LLC antibody did not permit consistent detection of ICs in ICGN tissue samples. Although there was reasonable inter-rater agreement, IHC using anti-canine LLC antibody had poor specificity and sensitivity in identifying ICGN cases.

Had IHC been a reliable tool for IC detection, it would be possible for many diagnostic laboratories to use the protocol without the need for a fluorescence microscope. This would mean pathologists with limited experience in the diagnosis of glomerular disease and the relevant IC deposition patterns might be asked to examine IHC-stained renal tissue. Therefore, we were also interested in determining agreement between a novice evaluator and a trained nephropathologist. This portion of our study demonstrated agreement between the 2 scorers, but both were often incorrect in the diagnosis when comparing IHC to the IF results. If reliable IHC techniques can be developed, intra-scorer agreement will need to be assessed on a larger scale using more pathologists with various degrees of experience.

Previous immunohistochemical studies of canine glomerular diseases used antibodies targeting Ig heavy chains.5,8–11 Sometimes IHC results were not confirmed with either IF or TEM.9,10 One study using antibodies targeting IgG, IgA, and IgM reported inconsistent IHC staining results.9 In addition, our experience and that of human renal pathology laboratories (Tibor Nadasdy, pers. comm., 2016) has revealed that anti-IgM IF antibodies often nonspecifically label glomeruli from many non-ICGN cases given that IgM is a large pentameric Ig that often gets entrapped in segmentally sclerotic glomeruli.13 Therefore, detecting IgM complexes is not a reliable indicator of IC deposition. In a previous study comparing IHC versus IF in detecting ICGN in human specimens, the specificity of the antibody could not be determined because negative controls (non-ICGN cases) were not used in the study.6 Overall, our data raise doubt as to whether studies using IHC antibodies (without confirmatory TEM) truly labeled IC deposits in canine glomeruli.

Our aim was to develop an alternative diagnostic tool to help minimize sample collection from patients and improve workflow for clinicians and laboratory personnel at the IVRPS. IHC using the anti-canine LLC antibody evaluated in our study did not deliver reliable results nor did it demonstrate staining patterns consistent with the gold standard tests. A better-optimized IHC using antibody against LLC or an alternative antibody should be considered for future comparisons of IF with IHC in differentiating ICGN from non-ICGN. Given that a reliable alternative diagnostic tool could not be developed, IF and TEM remain the mainstay and recommended tests for the detection of IC in cases of glomerulopathies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Table_1_from_author for Comparison of immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence techniques using anti- lambda light chain antibodies for identification of immune complex deposits in canine renal biopsies by Agnes Wong and Rachel E. Cianciolo in Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Garabed for assistance and feedback on our statistical analysis and interpretation. We also acknowledge the technical assistance provided by the Comparative Mouse Phenotyping Shared Resource (Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016058) for histopathology and electron microscopy specimen preparation. We also thank the World Small Animal Veterinary Association Renal Standardization Study Group for the conception and assistance in the development of the International Veterinary Pathology Service database.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This study was funded by revenue generated by the International Veterinary Renal Pathology Service.

References

- 1. Arun SS, et al. Immunohistochemical examination of light-chain expression (lambda/kappa ratio) in canine, feline, equine, bovine and porcine plasma cells. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A 1996;43:573–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burns J, et al. Intracellular immunoglobulins: a comparative study on three standard tissue processing methods using horseradish peroxidase and fluorochrome conjugates. J Clin Pathol 1974;27:548–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cianciolo RE, et al. Pathologic evaluation of canine renal biopsies: methods for identifying features that differentiate immune-mediated glomerulonephritides from other categories of glomerular diseases. J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:S10–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cianciolo RE, et al. World Small Animal Veterinary Association Renal Pathology Initiative: classification of glomerular diseases in dogs. Vet Pathol 2016;53:113–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dambach DM, et al. Morphologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural characterization of a distinctive renal lesion in dogs putatively associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection: 49 cases (1987–1992). Vet Pathol 1997;34:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davey FR, Busch GJ. Immunohistochemistry of glomerulonephritis using horseradish peroxidase and fluorescein-labeled antibody: a comparison of two technics. Am J Clin Pathol 1970;53:531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fritschy JM. Is my antibody-staining specific? How to deal with pitfalls of immunohistochemistry. Eur J Neurosci 2008;28:2365–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harris CH, et al. Canine IgA glomerulonephropathy. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1993;36:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jaenke RS, Allen TA. Membranous nephropathy in the dog. Vet Pathol 1986;23:718–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mancianti F, et al. Analysis of renal immune-deposits in canine leishmaniasis. Preliminary results. Parassitologia 1989;31:213–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poli A, et al. Renal involvement in canine leishmaniasis. Nephron 1991;57:444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schneider SM, et al. Prevalence of immune-complex glomerulonephritides in dogs biopsied for suspected glomerular disease: 501 cases (2007–2012). J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:S67–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwartz MM. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. In: Jennette JC, ed. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott & Williams, 2007:155. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singer J, et al. Generation of a canine anti-EGFR (ErbB-1) antibody for passive immunotherapy in dog cancer patients. Mol Cancer Ther 2014;13:1777–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walker PD. The renal biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Table_1_from_author for Comparison of immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence techniques using anti- lambda light chain antibodies for identification of immune complex deposits in canine renal biopsies by Agnes Wong and Rachel E. Cianciolo in Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation