Abstract

Objectives

To measure the prevalence of domestic violence among women attending general practice; test the association between experience of domestic violence and demographic factors; evaluate the extent of recording of domestic violence in records held by general practices; and assess acceptability to women of screening for domestic violence by general practitioners or practice nurses.

Design

Self administered questionnaire survey. Review of medical records.

Setting

General practices in Hackney, London.

Participants

1207 women (>15 years) attending selected practices.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of domestic violence against women. Association between demographic factors and domestic violence reported in questionnaire. Comparison of recording of domestic violence in medical records with that reported in questionnaire. Attitudes of women towards being questioned about domestic violence by general practitioners or practice nurses.

Results

425/1035 women (41%, 95% confidence interval 38% to 44%) had ever experienced physical violence from a partner or former partner and 160/949 (17%, 14% to 19%) had experienced it within the past year. Pregnancy in the past year was associated with an increased risk of current violence (adjusted odds ratio 2.11, 1.39 to 3.19). Physical violence was recorded in the medical records of 15/90 (17%) women who reported it on the questionnaire. At least 202/1010 (20%) women objected to screening for domestic violence.

Conclusions

With the high prevalence of domestic violence, health professionals should maintain a high level of awareness of the possibility of domestic violence, especially affecting pregnant women, but the case for screening is not yet convincing.

What is already known on this topic

Domestic violence is associated with a wide range of health and social problems for women and their children

Women experiencing violence are often not identified by health professionals in hospital settings

Professional organisations and politicians are promoting a policy of screening for domestic violence

What this study adds

Over a third of women attending general practices had experienced physical violence from a male partner or former partner

Most women who had experienced physical violence were not identified by general practitioners, according to data extracted from their medical records

Women pregnant in the previous year were at high risk for current physical violence

A substantial minority of women object to routine questioning about domestic violence

Introduction

Physical injury, mental health problems, and complications of pregnancy are some of the health consequences that result from violence inflicted on women by their male partners or former partners. Domestic violence is also associated with other abusive experiences that may occur during adulthood.1 Because domestic violence is common, serious, and often not identified, a recent British government publication recommended that health professionals should consider routinely asking all women, or selected groups of women, about a history of domestic violence.2 Ten years ago, the American Medical Association recommended screening all women presenting to primary care and many secondary care specialties3; recently, this policy has been questioned.4 Research findings do not clarify whether screening women for domestic violence meets accepted criteria for a valid screening procedure.5

Little research in the primary care setting has investigated domestic violence against women in the United Kingdom. Two small studies reported lifetime prevalences of domestic violence against women of 39% and 60%.6,7 A community survey found that 23% of women had ever been physically assaulted by a partner or former partner, with 4% experiencing violence within the previous 12 months.8 Recent primary care studies from outside the United Kingdom have reported rates of lifetime experience of domestic violence ranging from 12% to 46%9–11 and prevalences over the previous 12 months of 6% and 28%.12,13 The differences in prevalence are explained, in part, by the different definitions of domestic violence used in the studies. Some investigators focus on physical violence alone, whereas others include a broader range of abusive behaviours, including emotional and other non-physical abuse.Even these broader definitions of domestic violence fail to capture the complexity of abuse of women by men.14,15

Women experiencing domestic violence often are not identified by clinicians, and the success of general practitioners in recognising cases of domestic violence in the United Kingdom has not been investigated. Studies in accident and emergency departments have shown that most women who have experienced domestic violence are not identified by nurses or doctors.16 One study based on medical records in the primary care setting in the United States showed that fewer than 10% of women experiencing domestic violence had been identified by doctors.17

We do not know if screening for domestic violence in primary care is acceptable to women. Some evidence, mostly from community surveys, indicates that women want to be asked about domestic violence.18

Our study had four objectives: to measure the prevalence of domestic violence among women attending general practice; to test the association between experience of domestic violence and demographic factors to try to establish whether there is a high risk group of women for whom screening might be more appropriate; to compare the recording of domestic violence in general practice records with women's reported experience to measure the proportion of women experiencing domestic violence that is not detected; and to explore women's attitudes to being questioned about domestic violence by general practitioners or practice nurses.

Participants and methods

Between January and December 1999, we surveyed women (16 years or over) in 13 randomly selected general practices in the east London borough of Hackney. We designed a self administered questionnaire that incorporated questions used in a primary care study.19 The questions looked at different aspects of domestic violence (see table 2); for each question, the woman was asked to consider whether she had to be careful about what she said or did as a result of the man's behaviour. We also asked about the woman's attitude to being questioned by her general practitioner or practice nurse about abuse by her partner.

Table 2.

Prevalence of domestic violence. Values are numbers (percentages; 95% confidence intervals)

| Form of abuse | Total responses | Positive responses |

|---|---|---|

| Controlling behaviour by partner: | ||

| Shouted, screamed, or swore at you | 1054 | 649 (62; 59 to 65) |

| Criticised you | 1024 | 581 (57; 54 to 60) |

| Checked up on your movements | 1024 | 382 (37; 34 to 40) |

| Restricted your social life | 1028 | 352 (34; 31 to 37) |

| Tried to control you in any other way not involving physical violence | 1025 | 335 (33; 30 to 36) |

| Kept you short of money | 1028 | 258 (25; 22 to 28) |

| Locked you in the house | 1006 | 75 (7; 6 to 9) |

| Any controlling behaviour | 1060 | 789 (74; 72 to 77) |

| Threatening behaviour by partner: | ||

| Punched, kicked, or threw things | 1031 | 367 (36; 33 to 39) |

| Threatened you with fist, hand, or foot | 1035 | 292 (28; 26 to 31) |

| Threatened you with object or weapon | 1020 | 134 (13; 11 to 15) |

| Threatened to kill you | 1003 | 133 (13; 11 to 15) |

| Threatened the children | 909 | 68 (7; 6 to 9) |

| Any threatening behaviour | 967 | 441 (46; 43 to 49) |

| Physical violence by partner: | ||

| Grabbed or shoved you* | 1025 | 356 (35; 32 to 38) |

| Punched you on body/arms/legs* | 1020 | 206 (20; 18 to 23) |

| Punched you in the face* | 1022 | 167 (16; 14 to 19) |

| Forced you to have sex* | 1022 | 162 (16; 14 to 18) |

| Physically violent to you in other way* | 1004 | 157 (16; 13 to 18) |

| Kicked you on the floor* | 1015 | 134 (13; 11 to 15) |

| Choked or held hand over your mouth* | 1009 | 133 (13; 11 to 15) |

| Used weapon or object to hurt you* | 1010 | 73 (7; 6 to 9) |

| Tried to strangle, burn, or drown you* | 1008 | 72 (7; 6 to 9) |

| Hit or hurt the children† | 951 | 49 (5; 4 to 7) |

| Any physical violence | 1035 | 425 (41; 38 to 44) |

| Physical violence in the past twelve months | 949 | 160 (17; 14 to 19) |

| Do you think you have ever experienced domestic violence? | 1097 | 304 (28; 25 to 30) |

| Have you ever felt afraid of your partner? | 1044 | 369 (35; 32 to 38) |

Included in definition of physical violence used in analysis.

For those women with children.

The patients' characteristics are given in table 1. We used ethnic group categories defined by the East London and the City Health Authority; these are based on categories defined by the Office for National Statistics, but are modified to reflect local diversity. The questionnaire was piloted in one practice, after which minor changes were made to the wording and layout.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women answering a questionnaire about domestic violence. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Characteristic | Women |

|---|---|

| Age group (n=1182): | |

| 16-24 | 206 (17) |

| 25-34 | 455 (39) |

| 35-44 | 280 (24) |

| ⩾45 | 241 (20) |

| Ethnic group (n=1171): | |

| White: | |

| British | 475 (41) |

| Irish | 51 (4) |

| Other | 108 (9) |

| Black: | |

| African | 75 (6) |

| British | 88 (8) |

| Caribbean | 113 (10) |

| Other (including North African) | 12 (1) |

| Asian: | |

| Bangladeshi | 10 (1) |

| Indian | 32 (3) |

| Pakistani | 8 (1) |

| Turkish or Cypriot | 84 (7) |

| Other | 115 (10) |

| Born in United Kingdom (n=1178) | 761 (65) |

| Unemployed (n=1180) | 137 (12) |

| Home owner (n=1191) | 337 (28) |

| Car owner (n=1183) | 597 (50) |

| Less than 13 years of education (n=1050) | 554 (53) |

| Children (n=1198) | 730 (61) |

| Marital status (n=1165): | |

| Married | 413 (35) |

| Divorced or separated | 151 (13) |

| Widowed | 35 (3) |

| Single | 443 (38) |

| Cohabiting | 123 (11) |

The sample consisted of consecutive women attending the practices during time periods randomly selected for data collection. Women were eligible to participate if they were registered with the practice, were over 15 years old, and were able to read English, Turkish, or Bengali (the three languages in which the questionnaire was available). Those who were holding an infant or who were too unwell to complete the questionnaire were ineligible. Research assistants recruited women in the surgeries' waiting areas, and the women completed the questionnaire in the waiting areas.

We collected data on any disclosure or suspicion of domestic violence that was documented in the medical records. These data were extracted by investigators blinded to the responses on the questionnaire, and they were validated by two general practitioners in the research team, who independently extracted data from a random sample of 107 medical records. The validators' results were taken as the standard from which we estimated the true rate of recording of domestic violence.

Statistical methods

We entered information gathered from the questionnaire with a double data entry method. The data were analysed using SPSS. We report univariate analyses performed with the χ2 test for frequencies. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify demographic variables that were significantly related to domestic violence. For the purpose of this analysis, we included any woman who had ever experienced any type of physical violence, including forced sex from a partner or former partner. We defined current domestic violence as physical violence experienced during the past 12 months.

We calculated that we needed to recruit 913 women to have 90% power to show a 15% difference in a range of demographic variables and to be significant at the 0.05 level between women who had experienced physical violence within the previous 12 months and those who had not. We assumed that 15% of women in the community had experienced domestic violence within the previous 12 months. On the basis of this calculation, we collected data from 13 practices.

The study had approval from the East London and the City Health Authority research ethics committee.

Results

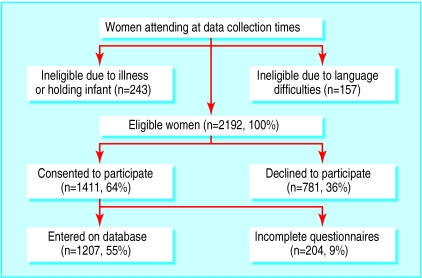

We approached 19 randomly selected practices to recruit 13 practices. In total, 1207 (55%) women were recruited (figure), comprising data collected from 5% of all registered women in 11 of the 13 practices. We aimed to review the patient's medical records for one in three randomly selected questionnaires. However, in only 258 of these randomly chosen questionnaires had the woman completing the questionnaire given consent for her medical records to be reviewed. The characteristics of the recruited women are shown in table 1.

Prevalence of domestic violence

Overall, 425 (41%) of 1035 women had ever experienced physical violence from a partner or former partner (table 2). In total, 789 (74%) of 1060 women had experienced any form of controlling behaviour by their partner and 441 (46%) of 967 had been threatened. When we asked “Do you think you have ever experienced domestic violence,” 304 (28%) of 1097 women responded positively; this was a smaller proportion than those who reported physical violence. Physical violence from a partner or former partner had been experienced by 160 (17%) of 949 women within the previous 12 months and 369 (35%) of 1044 had ever felt afraid of their current or former partner. Based on responses from 1040 women, 222 (21%) women had ever had injuries, including bruises or more serious injuries, from violence. Of the 222 women who had experienced injury, 110 (50%) had sought medical attention for their injuries. Domestic violence during pregnancy was reported by 15% (101/677) of respondents who had ever been pregnant; of these, 26/103 (25%) women reported that this violence was worse than when they were not pregnant and 31/106 (29%) stated that it had caused a miscarriage.

Risk factors

Table 3 shows the risk factors associated with current experience of physical violence from a partner or former partner. Multiple logistic regression showed that being divorced or separated, pregnant in the previous year, under 45, and unemployed were significantly associated with physical violence within the past 12 months. Being divorced or separated, single or cohabiting, having children, being pregnant in the past year, and being born in the United Kingdom were significantly associated with ever experiencing physical violence. Black women were least likely to have ever experienced physical violence.

Table 3.

Risk factors for current physical violence against women by their male partner or former partner. Values are numbers (percentages) unless otherwise specified

| Odds ratio (95% CI)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | All responses | No current physical violence* | Current† physical violence* | Prevalence (%)‡ | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

| All responses | 1207 | 789 | 160 | |||

| Age (years): | ||||||

| 16-24 | 167 | 134 (17) | 33 (21) | 20 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25-34 | 375 | 308 (40) | 67 (42) | 18 | 0.88 (0.56 to 1.40) | 0.85 (0.51 to 1.40) |

| 25-44 | 220 | 179 (23) | 41 (26) | 19 | 0.93 (0.56 to 1.55) | 0.86 (0.49 to 1.52) |

| ⩾45 | 173 | 155 (20) | 18 (11) | 10 | 0.47 (0.25 to 0.88) | 0.40 (0.19 to 0.85) |

| Missing responses | 272 | |||||

| Ethnic group:§ | ||||||

| White | 537 | 443 (58) | 94 (59) | 18 | 1.00 | |

| Black** | 213 | 184 (24) | 29 (18) | 14 | 0.74 (0.47 to 1.17) | |

| Asian | 36 | 31 (4) | 5 (3) | 14 | 0.76 (0.29 to 2.01) | |

| Other | 141 | 110 (14) | 31 (20) | 22 | 1.33 (0.84 to 2.10) | |

| Missing responses | 280 | |||||

| Born in United Kingdom: | ||||||

| No | 297 | 253 (33) | 44 (28) | 15 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 638 | 524 (67) | 114 (72) | 18 | 1.25 (0.86 to 1.83) | |

| Missing responses | 272 | |||||

| Marital status: | ||||||

| Married | 314 | 269 (35) | 45 (29) | 14 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Divorced or separated | 105 | 76 (10) | 29 (18) | 28 | 2.28 (1.34 to 3.88) | 3.37 (1.89 to 6.01) |

| Widowed | 28 | 24 (3) | 4 (3) | 14 | 1.00 (0.33 to 3.01) | 1.92 (0.59 to 6.26) |

| Single | 370 | 307 (40) | 63 (40) | 17 | 1.23 (0.81 to 1.86) | 1.16 (0.74 to 1.82) |

| Cohabiting | 103 | 87 (11) | 16 (10) | 16 | 1.10 (0.59 to 2.04) | 0.97 (0.51 to 1.85) |

| Missing responses | 287 | |||||

| Children: | ||||||

| No | 398 | 341 (43) | 57 (36) | 14 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 547 | 445 (57) | 102 (64) | 19 | 1.37 (0.96 to 1.95) | |

| Missing responses | 262 | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| <13 yrs | 421 | 343 (48) | 78 (56) | 19 | 1.00 | |

| ⩾13 yrs | 427 | 366 (52) | 61 (44) | 14 | 0.73 (0.51 to 1.06) | |

| Missing responses | 359 | |||||

| Unemployed: | ||||||

| No | 821 | 691 (89) | 130 (82) | 16 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 111 | 83 (11) | 28 (18) | 25 | 1.79 (1.12 to 2.86) | 1.71 (1.04 to 2.81) |

| Missing responses | 275 | |||||

| Homeowner: | ||||||

| No | 669 | 545 (70) | 124 (78) | 19 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 270 | 235 (30) | 35 (22) | 13 | 0.66 (0.44 to 0.98) | |

| Missing responses | 268 | |||||

| Car owner: | ||||||

| No | 458 | 377 (49) | 81 (52) | 18 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 476 | 400 (51) | 76 (48) | 16 | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.25) | |

| Missing responses | 273 | |||||

| Pregnant in past year: | ||||||

| No | 731 | 624 (81) | 107 (68) | 15 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 200 | 150 (19) | 50 (32) | 25 | 1.94 (1.33 to 2.84) | 2.11 (1.39 to 3.19) |

| Missing responses | 276 | |||||

Adjusted odds ratios are only presented for the variables that were identified as significant in the final model.

Totals vary because of missing data.

During past 12 months.

Percentage who have experienced physical abuse within each response category.

Grouped according to table 1 except “other” and “Turkish or Cypriot,” which are combined as “other” in this table.

Black includes Caribbean, African, Black British, and black other.

Recording of domestic violence in patients' records

The medical records of 258 women were reviewed. Of the 226 women who had completed the section of the questionnaire on physical violence, 90 (40%) reported that they had ever experienced physical violence from a partner. Definite or suspected domestic violence was recorded in the records of 15 (17%) of these. Definite or suspected physical violence by a partner or former partner was recorded in a further eight sets of records belonging to women who had not reported violence on the questionnaire. Physical violence by a partner or former partner was recorded in four sets of notes from 32 women who had not completed the physical violence section of the questionnaire. In total, domestic violence was identified, or thought likely, and documented in 27 (10%) of the 258 sets of notes that we examined.

Data extraction was validated in 107 sets of medical records. The true rate of recording of domestic violence in the medical records of women was calculated as 7% (95% exact binomial confidence interval 3% to 14%).

Attitudes to questioning

Overall, 34 (4%) women reported that they had ever been asked by their general practitioner if they had been hit, injured, or abused by a partner or former partner and 11 (1%) if they had been forced to have sex. Of those who had experienced physical violence, 64 (32%) reported they had told their doctor. In total, 82 (8%) women reported that they would mind “in general” if their doctor asked whether they had ever been threatened, hit, or hurt by a partner or former partner, with 114 (11%) minding a similar inquiry about forced sex. If the same questions were asked by a practice nurse, 119 (12%) and 136 (13%) women, respectively, said they would mind being asked. In total, 202 (20%) women reported that they would mind being asked by their general practitioner about abuse or violence in their relationship if they had come about something else, with 234 (23%) objecting to a nurse asking the same question (3% difference, 0.8% to 5.3%). The acceptability of being asked was not significantly different between women who were and were not currently experiencing domestic violence (data not shown). Overall, 432 (42%) women reported that they would find it easier to discuss these issues with a female doctor and 31 (3%) with a male doctor.

Discussion

We explored several issues pertinent to the introduction of screening for domestic violence in general practice, including the prevalence of the problem, the distribution of possible risk factors, current rates of identification, and the acceptability of routine questioning about domestic violence. Definitions of domestic violence vary; in our analysis, we focused on physical violence, including forced sex by a partner or former partner. This allowed us to compare our results with those from recent studies in primary care.9,10,12,13,20 The measurement of other forms of domestic violence is more complex, and their impact on the woman's health is less clearly defined.14,15

Prevalence of domestic violence

The number of women who had ever experienced physical violence in our study was towards the upper end of the range found in other surveys in primary care.9,10,12,20 The number of women who had experienced physical violence within the past 12 months was much higher than that in a study in the United States,12 which had a higher proportion of middle aged women, but was similar to that in other studies in primary care.13,20 Women reported a lower prevalence of domestic violence in response to a direct question (“Do you think you have ever experienced domestic violence?”) than in response to questions about physical violence. This discrepancy may be because women find it difficult to acknowledge the meaning of violence in their relationship21 or because of the contested definition of domestic violence.14,15 Until other prevalence studies from primary care are published in the United Kingdom, we will not know if these rates can be extrapolated to other geographical areas.

We do not know whether the low response rate in our study produced an overestimate or underestimate of prevalence. It would have been unethical to collect data from the medical records of women who declined to answer the questionnaire. It is possible that women experiencing physical violence were more likely to agree to participate. Even if all non-responders were women who had not experienced abuse, one in five women attending these general practices would have experienced physical violence from a partner or former partner; this shows that, in a sample of women visiting their general practitioners, domestic violence is a common problem. This finding, taken with results from other studies, means that domestic violence fulfils one of the criteria for screening in general practice—that the condition is an important health problem.

Identifying women who are experiencing violence

A prerequisite for preventing further morbidity is being able to identify women experiencing current violence. We investigated whether these women could be identified from demographic features; we found that divorced or separated women, those under 45, and unemployed women were at higher risk of current physical violence from a partner or former partner. Some of our findings are consistent with those of Mirrlees-Black,who found that the risks for physical assault were highest over the past 12 months in women aged 16-24, separated women, council tenants, and those in poor health or financial difficulty.8

Pregnancy and domestic violence

We found that pregnancy within the past 12 months doubled the risk of physical violence. The association between pregnancy and current violence is no greater than that for several other demographic factors in our study. Pregnancy is distinguished from other situations by the broader health consequences of violence—because the fetus is also at risk22—and the more severe violence that women experience during pregnancy. Regular contact with health professionals during pregnancy may make it easier for women to report the problem and for health professionals to provide support. In the report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths, the Department of Health recommends that routine questioning about domestic violence should be included as part of antenatal care.23 Our findings show that pregnant women are at high risk and that screening could be more appropriate for this group of women than for other groups.

Underidentification of domestic violence

Our results from general practice agree with other studies, which show that most women experiencing domestic violence are not identified in their medical records. Our estimate of underidentification is not precise, but it indicates that general practitioners fail to document a history of domestic violence in about three quarters of women who have experienced it. Is underidentification in medical records because women do not disclose their experience or because general practitioners do not record it? In our study, a third of women who had experienced physical violence reported telling their general practitioner. This suggests that under-recording of disclosure contributes to the gap between women's experiences and their medical records.

Women's attitudes to screening

About one in five women in our survey objected to the idea of routine questioning; this finding is comparable with those from other surveys, which showed that similar24,25 or higher26 proportions of women were opposed to screening. A survey in the United Kingdom has shown that the majority of primary care health professionals do not wish to engage in screening27; this concurs with the results of one North American study.24

Conclusion

A recent review concludes that women experiencing domestic violence are best identified by universal screening.28 Our findings about prevalence and identification rates lend weight to the case for women being screened, in general practice, for domestic violence. We found that pregnant women were at higher risk than other women, and this could support a case for selective screening in antenatal clinics. The large minority of women who object to routine questioning about domestic violence weakens the case for screening. The limited acceptability and, in particular, the absence of evidence of a benefit to women of screening for domestic violence in healthcare settings28 means that its introduction would be premature. In the meantime, health professionals should not ignore the seriousness of domestic violence. We need to be aware of the possibility of violence in the lives of our patients and to offer support as well as general advice and information about agencies that can provide help.

Figure.

Recruitment of participants

Acknowledgments

We thank the women who participated in this study and the practices that allowed us to recruit patients in their waiting rooms and gave us access to their medical records. The questionnaire was piloted in Lower Clapton Health Centre, part of the East London and Essex Network of Researchers.

Footnotes

Funding: Research grant from North Thames NHS Research and Development.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung W-S, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: a cross sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358:450–454. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domestic violence: a resource manual for health care professionals. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Medical Association diagnostic and treatment guidelines on domestic violence. Arch Fam Med. 1992;1:39–47. doi: 10.1001/archfami.1.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole TB. Is domestic violence screening helpful? JAMA. 2000;284:551–553. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health, UK National Screening Committee. The criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme. www.doh.gov.uk/nsc/pdfs/criteria.pdf (accessed 2 Nov 2001).

- 6.McGibbon A, Cooper L, Kelly L. What support? Hammersmith and Fulham council community police committee domestic violence project. London: Polytechnic of North London; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanko E, Crisp D, Hale C, Lucraft H. Counting the costs: estimating the impact of domestic violence in the London Borough of Hackney. London: The Children's Society and Hackney Safer Cities; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirrlees-Black C. London: Home Office; 1999. Domestic violence: findings from a new British crime survey self-completion questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freund KM, Bak SM, Blackhall L. Identifying domestic violence in primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:44–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02603485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marais A, de Villiers PJT, Moller AT, Stein DJ. Domestic violence in patients visiting general practitioners—prevalence, phenomenology, and association with psychopathology. S Afr Med J. 1999;89:635–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson M, Elliott BA. Domestic violence among family practice patients in midsized and rural communities. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, DeChant HK, et al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:737–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazza D, Dennerstein L, Ryan V. Physical, sexual and emotional violence against women: a general practice-based prevalence study. Med J Aust. 1996;164:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burge SK. How do you define abuse? Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:31–32. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner PJ, Mongan PF. Validating the concept of abuse. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:25–29. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gremillion D, Kanof E. Overcoming barriers to physician involvement in identifying and referring victims of domestic violence. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:769–773. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rath GD, Jarratt LG, Leonardson G. Rates of domestic violence against adult women by men partners. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1989;2:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullender A, Hague G. Policing and reducing crime. London: Home Office Research Development and Statistics Directorate; 2000. Reducing domestic violence . . . what works? Women survivors' views. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley F. Domestic violence and general practice. Should general practitioners routinely ask about it? BMJ. [PROOFREADER PLEASE CHECK REFERENCE]

- 20.Hamberger LK, Saunders DG, Hovey M. Prevalence of domestic violence in community practice and rate of physician enquiry. Fam Med. 1992;24:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harwin N. Domestic violence: understanding women's experiences of abuse. In: Friend J, Mezey G, Bewley S, editors. . Violence against women. London: Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 1998. pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mezey GC, Bewley S. Domestic violence and pregnancy. BMJ. 1997;314:1295. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7090.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health; Welsh Office; Scottish Office Department of Health; Department of Health and Social Services Northern Ireland. Why mothers die: report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom 1994-1996. London: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman LS, Samet JH, Roberts MS, Hudlin M, Hans P. Inquiry about victimization experiences. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1186–1190. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.6.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caralis PV, Musialowski R. Women's experiences with domestic violence and their attitudes and expectations regarding medical care of abuse victims. South Med J. 1997;90:1075–1080. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199711000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNutt L, Carlson BE, Gagen D, Winterbauer N. Reproductive violence screening in primary care: perspectives and experiences of patients and battered women. J Am Med Wom Assoc. 1999;54:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson J, Feder G, Eldridge S, Chung S, Coid J, Moorey S. Women who experience domestic violence and women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a survey of health professionals‘ attitudes and clinical practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:468–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson L, King V, Garcia J, Marchant S. Policing and reducing crime. London: Home Office Research Development and Statistics Directorate; 2000. Reducing domestic violence . . . what works? Health services. [Google Scholar]