Abstract

Visual loss in pregnancy may be caused by a variety of reasons including pituitary adenomas. Prolactinomas (PRLs) are the most common hormone-secreting tumours in pregnant women. As most PRLs present with menstrual abnormalities, infertility or galactorrhoea, they are most commonly diagnosed before pregnancy. We present the case of a 30-year-old primigravida who presented at 36+5 weeks gestation with headaches and left-sided visual loss. MRI of the pituitary gland confirmed a 10×11 mm left suprasellar mass. Results of her anterior pituitary function were unremarkable for her gestational age. Postpartum, she underwent an endoscopic endonasal resection of the pituitary tumour. The histology was consistent with a PRL. Literature review reveals only one possible case of a new diagnosis of a PRL during pregnancy. It highlights the importance to consider a wide range of differential diagnoses when assessing visual loss in pregnancy.

Keywords: endocrinology, pituitary disorders, neuro-ophthalmology, obstetrics and gynaecology, pregnancy

Background

Pregnancy may be associated with ocular changes both transient and permanent. The differential diagnoses of visual loss in pregnancy are wide and include enlargement of pituitary adenomas.1 The pituitary gland enlarges physiologically during pregnancy but this usually does not cause symptoms.2 Prolactinomas (PRLs) are the most commonly encountered pituitary tumours in women of childbearing age. However, as they often cause symptoms, such as reproductive dysfunction, they are usually diagnosed before pregnancy.3

Case presentation

A 30-year-old primigravida at 36+5 weeks gestation presented with a history of a severe headache 2 weeks earlier followed by a loss of vision in her left eye. Visual acuity was 7/7.5 in the right eye and 6/24 in the left eye.

The woman did not have symptoms suggestive of adrenocorticotropin/cortisol excess or deficiency, acromegaly, hypothyroidism or diabetes insipidus. She denied galactorrhoea, and her menses had been regular prior to spontaneously conceiving.

Investigations

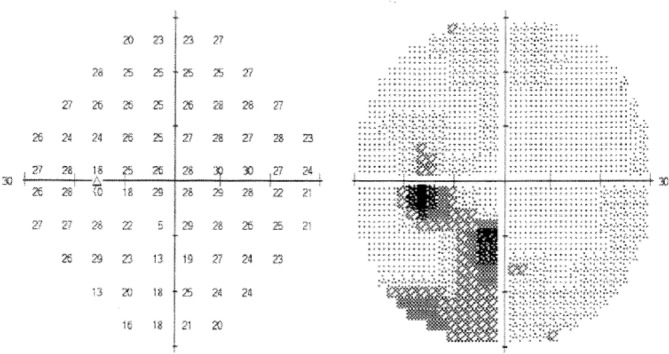

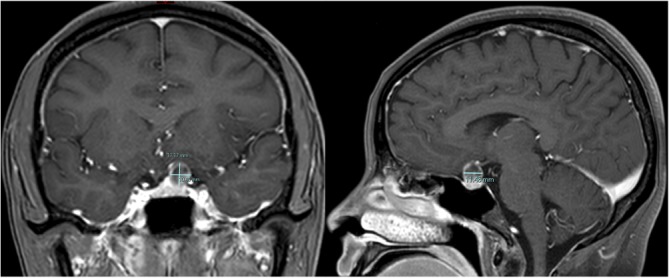

Visual field testing revealed inferotemporal visual loss in her left eye (figure 1). Her blood pressure and urine protein were normal. MRI of the pituitary showed a 10×11 mm left suprasellar mass compressing and elevating the left optic nerve, which remained unchanged on a repeated MRI with contrast postpartum (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Single field analysis of the left eye: inferotemporal field defect.

Figure 2.

Postpartum stealth protocol MRI with gadolinium enhancement, coronal (left) and sagittal (right) images: left suprasellar mass measuring 10×11×11 mm with localised mass effect with superior displacement and compression of the optic chiasm and left optic nerve.

The results of her biochemical investigations are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Anterior pituitary function tests

| Investigation | Result | Third-trimester normal range | Non-pregnant reference range |

| Prolactin (mIU/L) | 5087 | Vary according to laboratory and population | 80–450 |

| ACTH (ng/L) | 22 | 20–130 | 10–50 |

| Cortisol (nmol/L) | 656 | 350–1400 | 150–700 |

| IGF-1 (nmol/L) | 32 | 13–45 | 7–25 |

| fT4 (pmol/L) | 11.6 | 8–14 | 9–19 |

| fT3 (pmol/L) | 3.7 | 3–6 | 2.5–6 |

| TSH (IU/L) | 1.2 | 0.4–4.0 | 0.1–4 |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; IGF-1, insulin growth factor 1; fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free tetraiodothyronine; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Treatment

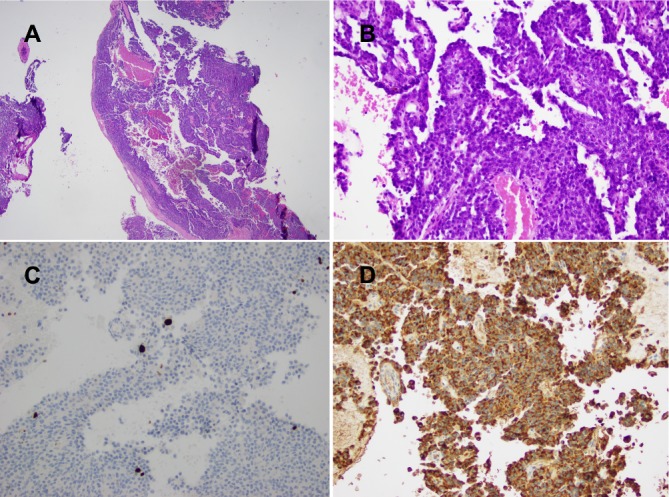

Dopamine agonists were not used as it was thought a PRL was unlikely in the absence of amenorrhoea, infertility or galactorrhoea preceding pregnancy, and with a prolactin level in the normal range for third trimester. The woman was also desirous of breastfeeding. At 37+2 weeks gestation, the patient was induced with epidural anaesthesia, but failed to establish labour, and she proceeded to a caesarean section, delivering a healthy boy with a birth weight of 2971 g. Postpartum, her visual field defect and pituitary tumour radiologically remained unchanged. One-month postpartum, stereotactic endoscopic endonasal resection of the pituitary tumour was performed. Histology revealed a sparsely granulated PRL with a proliferative fraction of less than 1% on Ki67. The tumour cells contained amphophilic cytoplasm and were positive for synaptophysin and negative for chromogranin. Immunohistochemistry for pituitary hormones showed strong paranuclear dot positivity for prolactin corresponding to the prominent Golgi zone (see figure 3), and was negative for thyroid-stimulating hormone, growth hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinising hormone and adrenocorticotrophic hormone.

Figure 3.

(A) Microscopic appearance of pituitary lesion (H&E stain, magnification ×20). (B) Microscopic appearance of basophilic tumour arranged in sheets and discohesive papillae with cells containing large nuclei with multiple nucleoli (H&E stain, magnification ×200). (C) Ki67 staining showing proliferative fraction of <1% (magnification ×200). (D) Immunohistochemistry with strong paranuclear dot positivity for prolactin (magnification ×200).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient’s visual defect resolved, her pituitary function was normal postoperatively and she continues to breastfeed. She is being followed-up in the endocrinology clinic on a regular basis.

Discussion

PRLs are the most common hormone-producing tumours in women of childbearing age.2 Most commonly, PRLs present with menstrual irregularities, infertility or galactorrhoea and as such are usually diagnosed before pregnancy.3 The normal pituitary gland increases by 50%–70% in size during pregnancy with an upward convexity of its superior surface due to lactotroph hyperplasia.4 This also results in a significant rise in prolactin levels. During pregnancy, there is a risk of PRL enlargement, which may lead to neurological sequelae, such as compression of the optic chiasm. If left untreated, macroadenomas have a 26% risk of tumour enlargement whereas the risk in microadenomas is much lower around 1.4%.3

Literature review with Medline, Google Scholar and PubMed only revealed one case of a newly diagnosed PRL during pregnancy. In this case, a 31-year-old woman described visual field defects on the left at 32 weeks gestation. At 36 weeks, she was subsequently diagnosed with left-sided temporal hemianopia and a non-contrast CT showed a pituitary adenoma measuring 2×1.5×2 cm with compression of the left optic chiasm. Her prolactin levels were elevated around 9000 mIU/L. She was diagnosed with a PRL and started on bromocriptine therapy, which led to a decrease in prolactin levels. She delivered at 37 weeks gestation. A contrast-enhanced CT 20 days postpartum showed no decrease in the overall size of the lesion. Eight months postpartum, her visual fields had normalised. The case report does not mention repeated CT scans or prolactin levels and does not mention if bromocriptine therapy was continued.5 The diagnosis of PRL was, therefore, not conclusive.

Serum prolactin levels rise significantly in an uncomplicated pregnancy. Reference intervals in the third trimester have been reported to range from 2130 to 12 765 mIU/L and 2915 to 7915 mIU/L.6 7 During the course of pregnancy, there is a gradual fall in high-molecular forms of prolactin such that these are present in only small amounts at term.8

In our case, prolactin levels were typical for the patient’s gestational age. Our patient conceived naturally and progressed to breastfeeding after delivery. Crosignani et al published a series of 29 spontaneous pregnancies in 28 women with mild hyperprolactinaemia.9 Only one woman had secondary amenorrhoea, sellar tomography was normal in 24 women, and the highest serum prolactin was reported as 100 ng/mL (2128 mIU/L) with the normal reference range being <20 ng/mL (426 mIU/L), with only seven women having a serum prolactin greater than 50 ng/mL (1064 mIU/L). Macroprolactin was not tested, and it is unclear how many of the women had underlying polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Pregnancy does not seem to have a significant effect on acromegaly, Cushing’s syndrome, thyroid stimulating hormone-producing pituitary tumours or non-functioning pituitary adenomas.3

In the absence of hormonal abnormalities at 36 weeks gestation, main differentials for visual field loss in the context of a pituitary lesion in our patient included a non-functioning pituitary adenoma, lymphocytic hypophysitis and pituitary enlargement due to pregnancy, craniopharyngioma and Rathke’s cleft cyst.

Two cases report visual field loss and blurred vision with compression of the optic chiasm by physiological enlargement of the pituitary at 30 weeks gestation.10 11 In both cases, the presentation was not felt to be consistent with lymphocytic hypophysitis and was thought to have occurred in the context of pregnancy-related increase of the pituitary gland. Follow-up imaging showed resolution of the pituitary mass in both cases.

An association of lymphocytic hypophysitis with pregnancy is common and this entity mostly presents in the last month of pregnancy or in the first 2 months postpartum.12 Patients commonly present with headache and partial hypopituitarism. MR characteristically shows thickening of the pituitary stalk, diffuse but symmetrical enlargement of the gland pituitary and/or a pituitary mass.13

Non-functioning pituitary adenomas have a prevalence of 7–41.3 cases per 100 000 of population.14 During pregnancy, enlargement of these tumours is possible but extremely rare.15

Learning points.

The pituitary gland increases physiologically during pregnancy.

Visual field loss in pregnancy can occur due to a pituitary lesion.

Prolactinomas are usually diagnosed prior to pregnancy but should be considered as a rare differential of a newly diagnosed pituitary mass in pregnancy.

Pregnancy-specific reference ranges should be used for interpretation of hormone levels in pregnancy.

Footnotes

Contributors: CAEB reviewed the patient as her function as an endocrinology advanced trainee with AM as the overseeing consultant. CS provided considerable input with the interpretation of histology results. All the authors contributed significantly to the care of the patient and had considerable input in the writing of this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Garg P, Aggarwal P. Ocular changes in pregnancy. Nepal J Ophthalmol 2012;4:150–61. 10.3126/nepjoph.v4i1.5867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gonzalez JG, Elizondo G, Saldivar D, et al. Pituitary gland growth during normal pregnancy: an in vivo study using magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Med 1988;85:217–20. 10.1016/S0002-9343(88)80346-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lambert K, Williamson C. Review of presentation, diagnosis and management of pituitary tumours in pregnancy. Obstet Med 2013;6:13–19. 10.1258/om.2012.120022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Randeva HS, Davis M, Prelevic GM. Prolactinoma and pregnancy. BJOG 2000;107:1064–8. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Von Versen-Höynck F, Schiessl K, Morgenstern B, et al. [Primary diagnosis of hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma during pregnancy and after birth -- a rare occurrence]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol 2004;208:150–4. 10.1055/s-2004-827221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sadovsky E, Weinstein D, Ben-David M, et al. Serum prolactin in normal and pathologic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1977;50:559–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abbassi-Ghanavati M, Greer LG, Cunningham FG. Pregnancy and laboratory studies: a reference table for clinicians. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:1326–31. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2bde8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pansini F, Bergamini CM, Malfaccini M, et al. Multiple molecular forms of prolactin during pregnancy in women. J Endocrinol 1985;106:81–5. 10.1677/joe.0.1060081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crosignani PG, Scarduelli C, Brambilla G, et al. Spontaneous pregnancies in hyperprolactinemic women. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1985;19:17–20. 10.1159/000299003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heald AH, Hughes D, King A, et al. Pregnancy related pituitary enlargement mimicking macroadenoma. Br J Neurosurg 2004;18:524–6. 10.1080/02688690400012517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inoue T, Hotta A, Awai M, et al. Loss of vision due to a physiologic pituitary enlargement during normal pregnancy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;245:1049–51. 10.1007/s00417-006-0491-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caturegli P, Newschaffer C, Olivi A, et al. Autoimmune hypophysitis. Endocr Rev 2005;26:599–614. 10.1210/er.2004-0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Honegger J, Schlaffer S, Menzel C, et al. Diagnosis of primary hypophysitis in Germany. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:3841–9. 10.1210/jc.2015-2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ntali G, Wass JA. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Pituitary 2018;21:111–8. 10.1007/s11102-018-0869-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pivonello R, De Martino MC, Auriemma RS, et al. Pituitary tumors and pregnancy: the interplay between a pathologic condition and a physiologic status. J Endocrinol Invest 2014;37:99–112. 10.1007/s40618-013-0019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]