Description

A 21-year-old male patient presented to the endocrine clinic with a history of congenital hypopituitarism. He had adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism and hypogonadism, which were being adequately replaced. At age 4, he was brought to the clinic with failure to thrive and small stature. He had no significant medical history or family history of short stature. Laboratory assessment revealed hypoglycaemia, low thyroxine, cortisol and adrenocorticotrophic hormone consistent with adrenal insufficiency. Growth hormone stimulation test revealed growth hormone deficiency. He was started on steroid, thyroid and growth hormone replacement. MRI of the pituitary gland (figure 1) showed an atrophic pituitary gland, absent pituitary stalk and an ectopic posterior pituitary consistent with pituitary stalk interruption syndrome (PSIS).

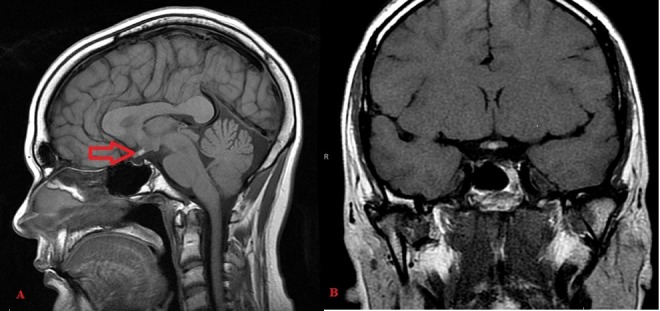

Figure 1.

(A) T1 sagittal image showing an atrophic pituitary gland and a 5 mm hyperintense focus in the retrochiasmatic region, which represents the ectopic posterior pituitary gland (red arrow). (B) T1 coronal image showing non-visualisation of the pituitary stalk.

PSIS is a congenital abnormality characterised by a triad of thin or interrupted pituitary stalk, small or absent pituitary gland, and an absent or ectopic pituitary gland. It was first described in 1987 by Fujisawa et al and had a reported incidence of 0.5/100 000 births.1 2 PSIS is believed to be either due to mutations in the genes involved in pituitary embryogenesis (PROP1, LHX3, HEXSX1, PROKR2 and GPR161) or perinatal asphyxia. PSIS can present with anterior pituitary hormone deficiencies (growth hormone, 100%; gonadotropin, 97.2%; corticotropin, 88.2%; and thyrotropin, 70.3%); however, hyperprolactinaemia (6.9%) due to lack of dopaminergic inhibition can be seen. Posterior pituitary function is intact. These anterior pituitary hormonal deficiencies can present as hypoglycaemia, neonatal jaundice, short stature, cryptorchidism, delayed puberty and micropenis. PSIS is also associated with other midline defects, such as broad nose, cleft lip and palate, single incisor, and nasal aperture stenosis.3 MRI shows the characteristic triad of absent pituitary stalk, anterior pituitary hypoplasia (98.3%) and ectopic posterior pituitary (91.2%). The ectopic neurohypophysis is most commonly seen in the infundibular recess (60.4%) or the hypothalamus (18.9%).4 PSIS is a rare condition and international databases need to be established to further study the molecular aetiology.

Learning points.

Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome is a congenital abnormality of the pituitary gland consisting of the triad of thin or interrupted pituitary stalk, small or absent anterior pituitary gland, and an absent or ectopic pituitary gland

It is characterised by deficiencies in the hormones secreted by the anterior pituitary gland, however mild hyperprolactinaemia may be seen. This is secondary to dopamine being unable to reach the pituitary and inhibit the lactotrophs as there is no pituitary stalk.

Clinically, it is characterised by hypoglycaemia, delayed puberty, short stature, micropenis, cryptorchidism and visual defects.

MRI is diagnostic showing an absent pituitary gland and an ectopic posterior pituitary.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK and SKG were involved in writing the manuscript. VVG was the senior author involved in editing the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Arrigo T, Wasniewska M, De Luca F, et al. Congenital adenohypophysis aplasia: clinical features and analysis of the transcriptional factors for embryonic pituitary development. J Endocrinol Invest 2006;29:208–13. 10.1007/BF03345541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fujisawa I, Kikuchi K, Nishimura K, et al. Transection of the pituitary stalk: development of an ectopic posterior lobe assessed with MR imaging. Radiology 1987;165:487–9. 10.1148/radiology.165.2.3659371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang CZ, Guo LL, Han BY, et al. Pituitary Stalk Interruption Syndrome: From Clinical Findings to Pathogenesis. J Neuroendocrinol 2017;29 10.1111/jne.12451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang Y, Guo QH, Wang BA, et al. Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome in 58 Chinese patients: clinical features and genetic analysis. Clin Endocrinol 2013;79:86–92. 10.1111/cen.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]