Description

Central venous catheters (CVCs) are a form of intravenous access usually indicated for infusions of vasoactive drips. CVCs are usually placed at bedside, aided by ultrasound or landmark guidance. Success of CVC placement is later confirmed via chest X-ray (CXR).1 A 40-year-old woman was transferred from an outside hospital because of septic shock due to soft tissue infection. Norepinephrine, propofol and normal saline were already infused via right internal jugular CVC. CXR showed the CVC crossing the mediastinum into the aorta and into the abdomen with the guidewire left in place (figures 1 and 2). Infusions through the CVC were discontinued, and we began using large-bore intravenous catheters and intraosseous access. Arterial blood gas (ABG) was drawn from the CVC, with results confirming arterial placement. A vascular surgeon was immediately contacted, but unfortunately, the patient passed away before any further intervention. Placement of CVC into arteries can cause pseudoaneurysms and embolic events; therefore, venous location should be confirmed via CXR. The tip of the catheter should be 4 cm above the carina in CXR.2 Also, pulling the CVC is not advised since this could cause damage to the endothelium, promoting aneurysms or rupture.3 If arterial puncture is suspected, infusions should be discontinued; an ABG should be obtained to confirm puncture; a neurological exam should be performed, if possible; and a vascular surgeon should be consulted.

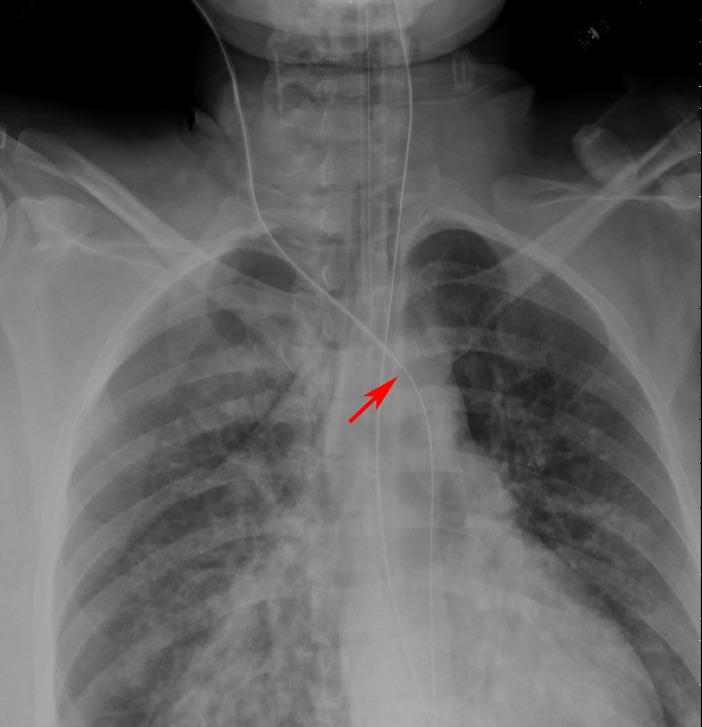

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray showing a central vein catheter crossing the mediastinum and going into the aorta; the red arrow shows the end of the central line catheter and the continuation of the guidewire.

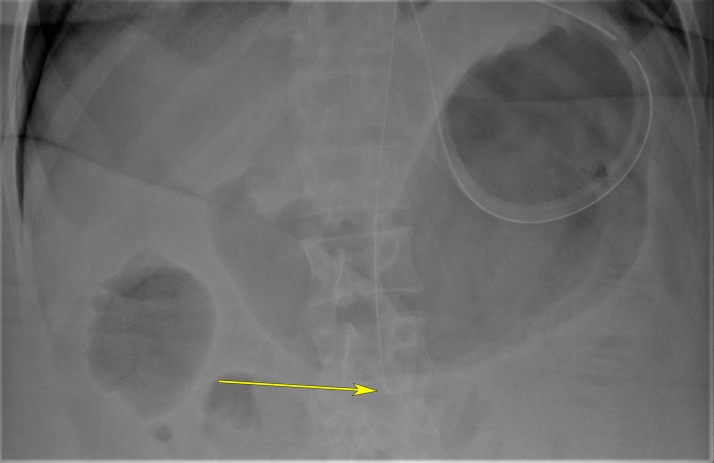

Figure 2.

Abdominal X-ray showing the tip of the central vein catheter guidewire in the abdominal aorta. The yellow arrow shows the end of the guidewire seen as a curvature.

Learning points.

Proper landmarking via chest X-ray for central venous catheter (CVC) placement (above the right mainstem bronchus) should be confirmed before it is used.

Drawing an arterial blood gas through the CVC can help guide the clinician if the placement was done in a venous or an arterial structure.

If the CVC was already used when the patient arrives, all infusions running through it should be discontinued, and quick access, such as an intraosseous or large-bore intravenous catheter, should be pursued. Due to the high risk of injury of these structures, the CVC should not be removed unless it is removed by a vascular surgeon.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Nikolay Azarov, Dr Alexander Bastidas and Dr Lavi Oud for their training on procedure performance, quality check and chest X-ray, small details that led us to discover the misplaced line.

Footnotes

GO, AMB, OG and AI contributed equally.

Twitter: @AlfredoIardinoS

Contributors: GO: manuscript description and writing, AMB: literature review, OG: preparation of images, AI: manuscript writing and final manuscript approval, and manuscript revision and editing. All the authors have the same levels of contribution.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Presented at: Will be presented at the American Thoracic Society 2019 in Dallas, Texas, USA

Patient consent for publication: Next of kin consent obtained.

References

- 1. Lee KA, Ramaswamy RS. Intravascular access devices from an interventional radiology perspective: indications, implantation techniques, and optimizing patency. Transfusion 2018;58(Suppl 1):549–57. 10.1111/trf.14501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albrecht K, Nave H, Breitmeier D, et al. Applied anatomy of the superior vena cava-the carina as a landmark to guide central venous catheter placement. Br J Anaesth 2004;92:75–7. 10.1093/bja/aeh013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guilbert MC, Elkouri S, Bracco D, et al. Arterial trauma during central venous catheter insertion: Case series, review and proposed algorithm. J Vasc Surg 2008;48:918–25. discussion 925 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]