Abstract

Adoptive transfer of T cells that express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) is an approved immunotherapy that may be curative for some hematological cancers. To better understand the therapeutic mechanism of action, we systematically analyzed prostate cancer-specific CAR signaling in human primary T cells by mass spectrometry. When we compared the interactomes and the signaling pathways activated by distinct CAR-T cells that shared the same antigen-binding domain but differed in their intracellular domains and their in vivo anti-tumor efficacy, we found that only second-generation CARs induced the expression of a constitutively phosphorylated form of CD3ζ that resembled the endogenous species. This phenomenon was independent of the choice of co-stimulatory domains, or the hinge/transmembrane region. Rather, it was dependent on the size of the intracellular domains. Moreover, the second-generation design was also associated with stronger phosphorylation of downstream secondary messengers, as evidenced by global phosphoproteome analysis. These results suggest that second-generation CARs can activate additional sources of CD3ζ signaling, and this may contribute to more intense signaling and superior antitumor efficacy that they display compared to third-generation CARs. Moreover, our results provide a deeper understanding of how CARs interact physically and/or functionally with endogenous T cell molecules, which will inform the development novel optimized immune receptors.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapies, such as Kymriah (CTL019, tisagenlecleucel) and Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel), can successfully treat B cell malignancies. Because these products are approved by the US FDA and by European regulatory agencies, there may be widespread implementation of this therapeutic modality. Thus, it is necessary to fully understand the mechanism of action of these biological therapies.

CARs are synthetic immune receptors introduced in T lymphocytes through gene engineering, which detect tumor-associated antigens and stimulate T cell activation to destroy target tumor cells (1). To emulate the function of endogenous T cell receptors (TCR), CARs use antigen-recognition domains derived from an antibody or other proteins with specificity for the target (2, 3) linked to an structural membrane-anchoring domain and a cytoplasmic tail that contains a T-cell activation domain derived from CD3ζ (1). Originally known as T-bodies almost 30 years ago (4), CARs now include co-stimulatory domains that allow for enhanced in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy (5).

Optimization of CAR design has been largely focused on the choice (and number) of co-stimulatory moieties that promote superior T cell function and persistence (1, 6, 7). CAR variations that contain CD27 (8)-, OX40 (9)-, CD28 (10)-, 4–1BB (11)-, or ICOS (12)-derived co-stimulatory sequences display mixed performance. Duong and collaborators suggest that mixing and matching multiple co-stimulatory domains using combinatorial libraries (13) may provide an additive improvement of CAR-T cell function. However, direct comparison of the efficacy of CAR constructs targeting prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA) indicates that a second-generation CAR containing the CD28 co-stimulation domain is more effective than a third-generation CAR, which contains both CD28 and 4–1BB domains (14). Thus, the effect of each additional signaling module is not additive and, in fact, can be detrimental. Beyond the co-stimulatory moieties, a handful of studies have focused on the optimization of the structural domains of the receptor, such as the length of the membrane-anchoring domains (15). In addition, CARs that contain a CD8α-derived transmembrane domain induce less activation-induced cell death of T cells than an equivalent CAR that contains a CD28-derived transmembrane domain (16).

CARs are thought to remain inactive, until they engage their cognate ligand. After ligation, they are assumed to signal linearly, recapitulating the activation of endogenous CD3ζ and CD28 pathways in T cells. Considering that the endogenous CD3ζ and CD28 receptors are spatially and temporarily segregated (17), but are fused together and activated simultaneously when part of a CAR, it is plausible that the nature of the downstream event will be different in the two different scenarios. A detailed understanding of the molecular mechanism of action of CARs, including well defined structure-function relationships, is essential for the development of novel and superior CAR-T therapies.

In the present study, we used immunoproteomics to characterize the proteins that interacted with CARs and participated in CAR-T cell signaling. Our data provide a system-level assessment of the CAR interactome in steady-state conditions, and a global analysis of the phosphorylation events that take place following CAR-T cell activation. Unlike previous reports (18, 19), we found that the length of the CAR endodomains determined their ability to interact with endogenous signaling molecules. This observation may explain why some CARs promote ligand-independent tonic signaling, which has been associated with premature loss of function (20), as well as differences between CARs in the initiation and amplification of T cell activation. To maximize the clinical relevance, this work was conducted entirely on human primary T cells transduced with CARs targeting PSCA, a surface protein overexpressed in multiple cancers including pancreatic (21), bladder (22), prostate, and lung (23, 24) tumors. An ongoing clinical trial is testing the safety of a similar anti-PSCA CAR (NCT02744287). Thus, as we move towards the clinical implementation of synthetic immunology products, these data may aid in the design of next-generation CARs and combination therapies (25).

Results

CAR expression promotes antigen-independent T cell activation

Our data indicates that a PSCA-specific second-generation CAR, which contains the CD28 transmembrane and co-stimulatory domains linked to CD3ζ (28t28Z), has superior antitumor capacity than a third-generation CAR of the same antigen specificity that contains the CD8 transmembrane sequence linked to both the CD28 and 4–1BB co-stimulatory domains and CD3ζ (8t28BBZ)(14). To better understand how these CAR designs influence T cell activation, we conducted a whole-transcriptome analysis on CD8+ PSCA-specific CAR-T cells or GFP-transduced controls prior to and 30 days after adoptive transfer into NSG mice with palpable subcutaneous HPAC pancreatic tumors (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed major differences in gene expression profiles of pre-infusion samples, whereas post-infusion samples from different groups overlapped substantially (Fig. 1B). Although the pre-infusion groups formed well-defined hierarchical clusters based on gene expression, post-infusion samples were separated from the pre-infusion group, but did not segregate on the basis of the transgene that they expressed (Fig 1C). We observed that multiple immune inhibitory receptors were differentially expressed between pre-and post-infusion CAR-T cells. The expression of PD-1 was increased in post-infusion samples when compared to pre-infusion cells (fig. S1, B and C), which recapitulates the results observed in patients treated with TCR-transgenic T cells (26). Similarly, TIGIT expression was also increased post-infusion CAR-T samples, whereas Tim-3 (also HAVCR) was decreased and there was no difference in the expression of CTLA4 (fig. S1, B and C). However, the pre-infusion PSCA-specific 28t28Z and 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells expressed slightly more CTLA4 and TIGIT than the GFP-transduced controls (fig. S1, B and C). Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis identified that multiple canonical pathways relevant to T cell function were differentially expressed between CAR-T cells and GFP-transduced controls, including IL-4 signaling, TCR signaling, JAK/STAT signaling (activated), NFκB signaling (inhibited), PI3K/AKT signaling (activated), among others (fig. S1D). These data suggest that CAR-T cells display gene expression signatures consistent with T cell activation. To confirm these findings, we transduced bulk T cells (CD8 and CD4) with GFP or a PSCA-specific 28t28Z or 8t28BBZ CAR, and assessed the expression of CD25 and CD69 after 14 days. We found that CD8+ CAR-transduced T cells increased the abundance of both of these activation markers more than GFP-transduced control T cells (Fig 1D). Moreover, T cells that expressed the CAR construct had more CD69 and CD25 that CAR-negative T cells present in the same culture (fig. S2A). Similar results were observed for CD4+ cells (fig. S2B and C). These data suggest that CAR expression promotes strong T cell activation, even in absence of further stimulation.

Fig. 1. CARs alter gene expression.

(A) Schematic of the transmembrane and co-stimulatory domains contained in the PSCA-specific second-generation 28t28Z and third-generation 8t28BBZ CARs studied in these experiments. (B and C) Affymetrix microarray analyses were performed in GFP-transduced human lymphocytes and PSCA-28t28Z or PSCA-8t28BBZ CD8+ CAR-T cells before (Pre) or after (Post) adoptive transfer into NSG mice. Principal component analysis (B) and Hierarchical clustering of differentially-expressed genes (C) are from the analysis of at least 3 biological replicates. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of CD69 and CD25 abundance on pre-infusion (day 12) CD8+ T cells that expressed GFP or CARs, as indicated. Histograms are representative of 4 independent experiments. (E) Number of differentially-expressed genes in PSCA-8t28BBZ (blue) or PSCA-28t28Z (red) CAR-T cells. Gene-set enrichment analysis (bar charts) was performed on the genes differentially expressed by each population or both populations compared to GFP controls. Data are from the analysis of at least 3 biological replicates. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of the in vitro proliferation of T cells transduced with GFP-control or the indicated CARs compare to non-transduced cells in the same culture. Histograms are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Based on these results, we cannot attribute the differences in antitumor performance observed for PSCA-28t28Z and PSCA-8t28BBZ to the in vivo acquisition of any specific transcriptional program, or to the upregulation of specific inhibitory receptors. This may be in part due to the fact that T cells were analyzed 30 days after adoptive transfer, and any change in their transcriptome may be masked by the influence of host tissues. However, those functional differences could be associated with the striking differences in gene expression patterns observed prior to adoptive cell transfer. We found a total of 1576 genes were differentially expressed between PSCA-specific 28t28Z CAR-T cells and GFP-transduced controls (Fig 1E). Similarly, we found 524 genes were differentially expressed between PSCA-specific 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells and GFP-transduced controls. Of those, 424 genes were differentially expressed in both CAR-T cell groups, compared to the GFP-transduced controls. Gene set enrichment analyses showed that genes involved in IL-2 and STAT5 signaling were altered in all comparisons (Fig. 1E and fig. S2E). In addition, cells that expressed either CAR proliferated more in the absence of further stimulation than GFP-transduced controls or CAR-negative cells in the same culture (Fig. 1F and fig. S2D). Altogether, these results suggest the expression of a CAR in human T cells can induce dramatic changes in gene expression profiles, proliferation patterns, and in activation status (even in absence of antigen recognition), which are associated with differences in their in vivo anti-tumor capacity.

Immuno-mass spectrometry identifies candidate CAR interaction partners

Because the PSCA-specific CARs use the identical single chain fragment hinge (scFv) antibody domains for target recognition, we reasoned that the differences we observed in CAR-T cell activation may depend on the CAR endodomains and the interacting proteins, which influence their signaling properties. To identify the signaling molecules that interact with distinct CARs in steady state, we directly immunoprecipitated PSCA-specific 28t28Z or 8t28BBZ CARs using protein L beads (27), which binds to the kappa light chain of the CAR scFv, from lysates of CAR-T cells or GFP controls 14 days after transduction. We then analyzed the immune complexes by tandem liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and the identified peptides were mapped to their protein of origin and quantified (Fig. 2A). We identified peptides from a total of 6293 different proteins, which were used as the reference population for enrichment analyses. The 253 potential CAR interaction partners were defined based on differential abundance between samples expressing CAR and GFP-transduced cells (table S.1 and fig. S3A). Within this population, 15 canonical pathways were significantly enriched, including some with a major involvement in T cell function, such as Agranulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis, Calcium Signaling, Actin Cytoskeleton Signaling, T Helper Cell Differentiation, Integrin-Linked Signaling, Th2 Pathway, among others (Fig. 2B). We further focused on the top 34 candidates ranked by SaintScore, which incorporates topological properties of protein-protein interactions, that were the more abundant in the immunoprecipitates of either group of CAR-T cells (Table 1). The abundance fold change of the identified candidates in CAR-T cells compared to GFP-controls (Y-axis) correlated to their normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF, X-axis) (28), which discerned between proteins found in apparent high abundance due to their physical size (yielding more peptides detectable by MS) from those that were actually highly represented (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Proteomic-based CAR interactome analysis.

(A) Schematic of the immunoprecipitation tandem liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry experiment on PSCA-28t28Z and PSCA-8t28BBZ CAR-T cells and GFP controls. (B and C) Proteomics data analysis of the proteins enriched in lysates of CAR-T cells immunoprecipitated for CAR. Ingenuity canonical pathway analysis (B) or top interaction partners (C) with PSCA-28t28Z (left) and PSCA-8t28BBZ (right) are from the analysis of 3 biological replicates. Arrow indicates CD3ζ (CD247).

Table 1.

Top interaction partners (SaintScore>0.8).

| Protein | Gene | Description | FC PSCA-28t28Z/Bg | FC PSCA-8t28BBZ/Bg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P10747 | CD28 | CD28 Molecule | 50.8 | 13.8 |

| P20963 | CD247 | CD247 Molecule | 26.2 | 7.8 |

| O76038 | SCGN | Secretagogin, EF-Hand Calcium Binding Protein | 16.1 | 6.9 |

| Q6UXE8 | BTNL3 | Butyrophilin Like 3 | 11.2 | 3.9 |

| Q86YT6 | MIB1 | Mindbomb E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 1 | 9.5 | 14.5 |

| Q07020 | RPL18 | Ribosomal Protein L18 | 6.2 | 6.4 |

| Q9NQA5 | TRPV5 | Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 5 | 6.2 | 3.2 |

| Q9NPJ6 | MED4 | Mediator Complex Subunit 4 | 5.8 | 3.4 |

| Q5JQF8 | PABPC1L2A | Poly(A) Binding Protein Cytoplasmic 1 Like 2A | 5.5 | 2.6 |

| P37173 | TGFBR2 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor 2 | 5.2 | 2.5 |

| Q86Y07 | VRK2 | Vaccinia Related Kinase 2 | 5.0 | 3.5 |

| Q8NI08 | NCOA7 | Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 7 | 4.9 | 1.3 |

| Q01650 | SLC7A5 | Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 5 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| Q96Q89 | KIF20B | Kinesin Family Member 20B | 3.9 | 4.9 |

| Q9NX24 | NHP2 | NHP2 Ribonucleoprotein | 3.8 | 3.3 |

| Q8N5M4 | TTC9C | Tetratricopeptide Repeat Domain 9C | 3.8 | 4.0 |

| P24394 | IL4R | Interleukin 4 Receptor | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| C9J069 | C9orf172 | Chromosome 9 Open Reading Frame 172 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| Q16658 | FSCN1 | Fascin Actin-Bundling Protein 1 | 3.5 | 2.7 |

| Q9Y6Y1 | CAMTA1 | Calmodulin Binding Transcription Activator 1 | 3.4 | 7.9 |

| O94768 | STK17B | Serine/Threonine Kinase 17b | 3.4 | 2.2 |

| P46779 | RPL28 | Ribosomal Protein L28 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

| Q9Y3U8 | RPL36 | Ribosomal Protein L36 | 3.3 | 3.8 |

| P02786 | TFRC | Transferrin Receptor | 2.9 | 4.2 |

| Q70IA8 | MOB3C | MOB Kinase Activator 3C | 2.7 | 10.6 |

| Q2TAC2 | CCDC57 | Coiled-Coil Domain Containing 57 | 2.3 | 3.9 |

| H7BZ55 | CROCC2 | Ciliary Rootlet Coiled-Coil, Rootletin Family Member 2 | 2.0 | 6.2 |

| Q8N3Y7 | SDR16C5 | Short Chain Dehydrogenase/Reductase Family 16C Member 5 | 1.9 | 4.1 |

| P41219 | PRPH | Peripherin | 1.8 | 4.9 |

| O60343 | TBC1D4 | TBC1 Domain Family Member 4 | 1.0 | 6.1 |

| Q96PB1 | CASD1 | CAS1 Domain Containing 1 | 0.5 | 133.6 |

| Q9NPG4 | PCDH12 | Protocadherin 12 | 0.4 | 9.3 |

Among the most abundant proteins associated with PSCA-specific CARs, we found that CD3ζ (CD247) and CD28 in samples from both 28t28Z and 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells, SCGN and BTNL3 primarily in 28t28Z CAR-T cells and CASD1 in only in 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells. We validated some of the potential CAR interaction partners identified by mass spectrometry. BTNL3, for instance, was found in association with PSCA-specific 28t28Z CARs, but not 8t28BBZ CARs by western blot (fig. S4A). We also found that the membrane expression of IL2RB (also CD122) was increased in second generation CAR-T cells using flow cytometry (fig. S4B). Additionally, we found that the differences in CAR interactomes cannot be attributed to differences in differentiation state or different ratios of CD4/CD8 cells in the cultures, because they were uniform among samples (fig. S4C and fig. S4D). These results suggest that the specific signaling domains of a CAR may influence, and be influenced by, a complex network of proteins that exceeds the secondary messengers downstream of CD3ζ, which they were designed to activate upon antigen recognition.

Second generation CARs associate with an additional CD3ζ-containing protein

We were not surprised to find CD3ζ in high abundance when we immunoprecipitated cell surface CARs from CAR-T cells because it was integrated into both CARs. However, we unexpectedly found that CD3ζ (also CD247) was 3.4 times more abundant in association with PSCA-specific second-generation 28t28Z CAR than with third-generation 8t28BBZ CAR, despite the comparable amount of CAR on the cell surface (Fig. 3, A and B). This difference was only partially explained by differences in the abundance of immunoprecipitated CAR scFv, which was 1.5-fold more abundant in mass spectrometry data from 28t28Z CAR-T cells than 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells (fig. S3B). These data suggested that an additional source of CD3ζ may associate with the CARs in a domain-specific manner. When we analyzed the presence of CD3ζ by Western blot in lysates from control and PSCA-specific CAR-T cells, we found that only 28t28Z CAR-T cells contained a band that ran slightly over 20kDa, that we called CD3ζp21 (Fig. 3C and fig. S3C). In contrast, all primary human T cells contained a band corresponding to the endogenous CD3ζ monomer (16 kDa approximately), and we detected a higher molecular weight (between 55–75kDa) band that corresponded to either the 28t28Z or 8t28BBZ PSCA-specific CARs themselves. When the CAR scFv was immunoprecipitated, CD3ζp21 was also detected. We also observed the CD3ζp21 band in Jurkat J.RT3-T3.5 cells transduced with PSCA-specific 28t28Z CAR (fig. S5A). In these cells we also detected pZAP70, which suggested this CAR stimulated spontaneous signaling. These data agree with our gene expression results indicating second generation CARs spontaneously activated TCR signaling pathways (Fig. 1E and fig. S1D).

Fig. 3. CARs interact with CD3ζp21.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of CAR abundance on PSCA-28t28Z (red), PSCA-8t28BBZ (blue), or GFP (gray)-transduced T cells. Histograms are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B and C) Western blot analysis of CD3ζ interaction in lysates of T cells transduced with PSCA-28t28Z, PSCA-8t28BBZ, or GFP and immunoprecipitated for the CAR scFv. Blots (C) are representative of 8 independent experiments. (D) Schematic CAR designs with different transmembrane, hinge and co-stimulatory domains. (E and F) Western blot analysis of CD3ζ association in lysates of T cells transduced with the indicated CAR and immunoprecipitated for CAR scFv. Blots (E) are representative of 10 independent experiments. Quantified band intensity values (F) compared to the endogenous CD3ζ p16 (red) or CD3ζ-CAR p55/p75 (blue) are data with means ± SD from all experiments. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 by Friedman ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

Because 28t28Z and 8t28BBZ CARs differed in their hinge/transmembrane domain and co-stimulatory domains, we modified PSCA-specific CARs to contain distinct combinations of these elements to interrogate whether any of those specific elements promoted CAR interaction with CD3ζp21 (Fig. 3D). We generated modified second-generation CARs that contained a hinge/transmembrane domain derived from CD8α and a single co-stimulatory domain derived from either CD28 (8t28Z) or 4–1BB (8tBBZ). We also generated a modified third-generation CAR that contained a hinge/transmembrane domain derived from CD28 and the CD28 and 4–1BB co-stimulatory domains (28t28BBZ). We found that CD3ζp21 co-immunoprecipitated with all second-generation CARs, regardless of their hinge/transmembrane domains (Fig. 3E and F). Co-stimulatory domains also did not affect CD3ζp21 binding, as CD3ζp21 associated with both CD28 and 4–1BB-containing second generation CARs. This pattern of CD3ζ association with CARs was consistent across multiple donors (fig. S5D and fig. S5E). These data suggest that CD3ζp21 associates selectively with second-generation CARs in human T cells.

Second generation CARs induce expression of a constitutively phosphorylated form of CD3ζ

In activated T cells, phosphorylated CD3ζ runs at an apparent molecular weight of 21–23kDa, similar to CD3ζp21 (29–32). Therefore, we evaluated the phosphorylation status of CD3ζ in CAR-T cells by western blot with phosphospecific antibodies for CD3ζ-Tyr142, which is present in the third immunoreceptor tyrosine activation motif (ITAM) of CD3ζ. We found that the five versions of PSCA-specific CARs (28t28Z, 8t28BBZ, 8t28Z, 28t28BBZ, and 8tBBZ) were phosphorylated in the Tyr142 residue of CAR-bound CD3ζ, in absence of antigenic stimulation (Fig. 4A). However, only T cells expressing the second-generation CARs had a smaller band detected by the anti-CD3ζ-Tyr142 antibody. This phosphorylated species of CD3ζ immunoprecipitated with the second-generation CARs, which suggested that they physically interacted (Fig. 4B and C). We also detected phosphorylation of the CARs themselves at CD3ζ-Tyr72 (Fig. 4A), but we did not find CD3ζp21 phosphorylated at this site (fig. S5B). We also used mass spectrometry to analyze the phosphorylation status of CD3ζ immunoprecipitated from PSCA-specific 8tBBZ CAR-T cells after resolution of the 20–25kDa species by SDS-PAGE. We found that CD3ζ of this size were phosphorylated at Tyr142 and also in Tyr123 in 8tBBZ CAR-T cells (Fig. 4D). MS/MS spectra corresponding to the unphosphorylated peptides encompassing Tyr142 and Tyr123 are shown for reference (fig. S5C).

Fig. 4. Second-generation CARs constitutively phosphorylate CAR and CD3ζp21/23.

(A to B) Western blot analysis of pCD3ζ within the indicated CAR (A) and with the associated CD3ζ p21/p23 isoform (B) in lysates of T cells transduced with the indicated CAR and immunoprecipitated for CAR scFv. Blots (A and B) are representative of 3 independent experiments. Quantified band intensity values (C) are data with means ± SD from all experiments. (D) Tandem MS/MS analysis of pTyr142 (top) and pTyr123 (bottom) of immunoprecipitated CD3ζ species within 21–25kDa, from lysates of PSCA-8tBBZ CAR-T cells. Spectra are representative of the analysis of 3 biological replicates. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ns, not significant by Paired one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s post-test

To test whether the association with CD3ζp21 and the induction of spontaneous CD3ζ-Tyr142 phosphorylation were an exclusive feature of PSCA-specific CARs, we analyzed the CD3ζ association with Her2/Neu-specific CARs of various formats. Again, we found that only second-generation 28t28Z or 8t28Z CARs associated with CD3ζp21 (fig. S6A), which was associated with increased phosphorylation of CD3ζ-Tyr142 when compared to the third-generation 8t28BBZ CAR, as measured by flow cytometry (fig. S6B). We also tested CD3ζp21 association with a CD19-specific CAR (FMC63–28Z (33)) used in several clinical trials (34, 35). Similarly, we observed that CD3ζp21 also interacted with this second-generation CD19-sepcific CAR, which was phosphorylated at CD3ζ-Tyr142 (fig. S6C). Collectively, these results indicate that second-generation CARs promote CD3ζp21 expression and CAR association regardless of antigen specificity. Thus, second generation CARs may induce tonic signaling through both autophosphorylation of the CARs CD3ζ moiety, and constitutive activation of a separate CD3ζ species.

An extension of 24 amino acids in the CAR endodomain prevents the expression of CD3ζp21

We further examined to what extent the total size of the CAR intracellular domain influenced the appearance of the CD3ζp21 isoform. To do so, we replaced the 4–1BB co-stimulatory domain of the PSCA-specific third-generation 8t28BBZ CAR with a spacer of approximately the same size that consisted of 3 repeats of the (G4S)3 linker (8t28(G4S)3Z). We found that neither 8t28BBZ nor 8t28(G4S)3Z CARs increased the abundance of CD3ζp21 (fig. S6D). These data indicated that the presence of the specific 4–1BB domain sequence in the original third-generation CAR was not responsible for its lack of effect on the appearance of CD3ζp21. We also generated an extended version of the PSCA-specific second-generation 8t28Z CAR, by adding 24 additional amino acids from the C-terminus of CD8α in between the CD8α transmembrane domain and the CD28 co-stimulatory domain (8t(+24)28Z). Although the surface expression of PSCA-specific 8t28Z and 8t(+24)28Z CARs were comparable (Fig. 5A), we found that this modification reduced the abundance of CD3ζp21 and interaction of the CAR with CD3ζp21 (Fig. 5B and C). Similarly, this modification also reduced the pCD3ζ-Tyr142 detected by flow cytometry when compared to PSCA-specific 8t28Z CAR-T cells (fig. S6E). Extension of the second generation CAR also reduced the amount of IFNγ produced when CAR-T cells were co-cultured with PSCA+ HPAC cells compared to the parental PSCA-8t28Z CAR (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that the length of the CAR intracellular signaling domains regulates its interaction with CD3ζp21, which augments CAR-T cell function.

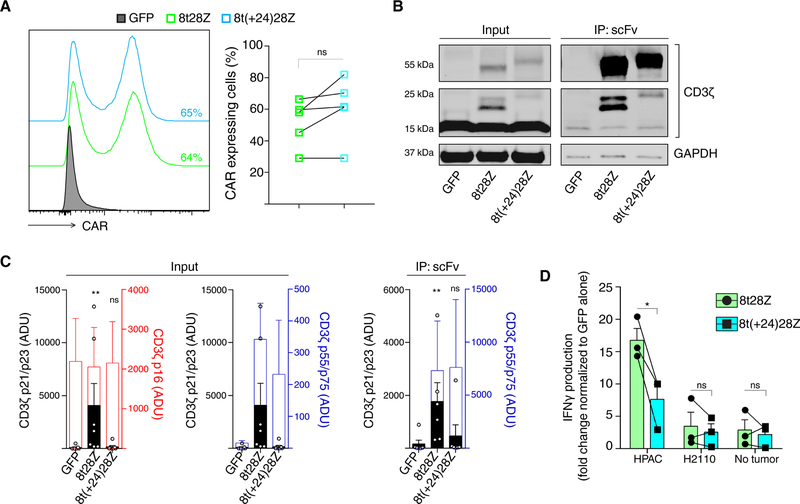

Fig. 5. The CAR endodomain size determines its ability to interact with CD3ζp21.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of CAR abundance on PSCA-8t28Z (green) and PSCA-8t(+24)28Z (light blue) and GFP (gray)-transduced T cells. Histograms (left) are representative of 5 independent experiments. The frequency of CAR+ cells was quantified for each donor (lines). (B and C) Western blot analysis of CD3ζ association with the indicated CAR in lysates of CAR T cells immunoprecipitated for CAR scFv. Blots (B) are representative of 7 independent experiments. Quantified band intensity values (C) compared to the endogenous CD3ζ p16 (red) or CD3ζ-CAR p55/p75 (blue) are data with means ± SD from all experiments. (D) ELISA analysis of IFNγ production by CAR-T cells normalized to the amount produced by GFP-T cells after overnight incubation with HPAC, H2110 cells or media alone (No tumor). Data and means ± SEM are from 3 independent experiments with lines connecting each independent donor analyzed. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ns; not significant by Paired t-test (A and D), Friedman ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison test (C) or two-way ANOVA (D).

Second generation CARs promote stronger TCR signaling than third generation CARs

In an attempt to understand how CD3ζp21 association influences CAR-T cell signaling, and to characterize the signaling properties of second-and third-generation CARs, we analyzed the phosphorylation events that take place after CAR engagement, by SILAC mass spectrometry (36). We co-cultured PSCA-specific CAR-T cells with heavy carbon isotope (13C6)-labeled tumors cells that express PSCA (Fig. 6A). This method facilitated a more realistic activation of CAR-T cells than antigen immobilized on plastic or other inert support, which may not reflect the antigenic density found on mammalian cells and lacks contribution from other membrane interactions, such as adhesion molecules. Labeling of tumor cells allowed us to discriminate, through post-hoc analyses, the mass-spectrometry signals corresponding to the T cells, from those corresponding to the tumor cells. We analyzed tryptic digests of lysates from PSCA-specific 28t28Z and 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells or GFP-transduced controls 1 hour after exposure to PSCA+ HPAC cells that were immunoprecipitated for pTyr. We identified 40 individual pTyr events in immunoprecipitates, and 751 individual pSer or pThr events in the flow through. Among those, the abundance of 40 phosphopeptides (20 pY and 20 pS/pT) was significantly different when comparing the CAR-T cells and the GFP control cells. Network-wide analysis of the integrated interactome and phosphoproteome revealed cross-talking functional modules including TCR signaling, cell cycle and the CAR interactome (fig. S7). Several canonical pathways were overrepresented within the group of differentially phosphorylated proteins, including TCR signaling, PKCtheta signaling, actin cytoskeleton signaling, and glycolysis, among others (Fig. 6B, fig. S8 and fig. S9).

Fig. 6. CAR signaling upon antigen binding.

(A) Experimental design for the comparison of PSCA-28t28Z and PSCA-8t28BBZ signalosome. Heavy isotope-labeled HPAC tumor cells were co-cultured with unlabeled GFP-transduced or CAR-T cells for 1 hour, then lysed and trypsin digested. Tandem mass spectrometry analysis was performed on pY peptides concentrated by immunoprecipitation and pS/pT peptides from the flow-through. (B and C) Proteomics data analysis of the 40/751 phospho-proteins that were differentially abundant in CAR-T cells when compared to background controls. Ingenuity pathway analysis (B) is representative of the analysis of 3 biological replicates. Abundance data on selected phosphopeptides relevant to TCR signaling in PSCA-28t28Z (red), PSCA-8t28BBZ (blue), or control CAR-T cells (black) and means ± SEM are from all samples. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001 by t-test.

Differences in phosphorylation between CAR-T cells and GFP-transduced controls were consistently greater in magnitude in the second-generation 28t28Z CAR-T cells than in third-generation 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells. For instance, the TCR signaling proteins CD3ζ, CD28, ZAP70, and LCK were phosphorylated more in 28t28Z CAR-T cells than 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells or GFP-controls (Fig. 6C). By Western blot, we observed that the basal phosphorylation of LCK at Tyr192 and Tyr505 were comparable between CAR-T cells and GFP controls (fig. S10). Together, these data suggest that increased pLCK detected in SILAC experiments may result from antigen-driven stimulation of the CAR. We also detected phosphorylation of CD3ζ at Tyr72, Tyr83 and Tyr123 as well as CD28 at Tyr191, Tyr206, Tyr209 and Tyr218. NetworKIN kinase prediction suggested that these phosphosites may be regulated directly by Src family kinases LCK/FYN/YES (CD3ζ) and Tec family kinases ITK/TEC/BMX (CD28) (fig. S11). In contrast, we found PAG1 was hypophosphorylated in PSCA-specific 28t28Z CAR-T cells when compared to GFP-transduced controls, whereas its phosphorylation in PSCA-8t28BBZ CAR-T cells was not significantly different from the controls. Additionally, we found the phosphorylation of GRAP2 was increased in PSCA-specific 8t28BBZ CAR-T cells when compared to GFP-transduced controls or 28t28Z CAR-T cells. The observation of more intense CAR-triggered changes in second-generation CAR-T cells compared to third-generation counterparts was consistent across the board, as illustrated for the glycolysis, STAT3, and actin cytoskeleton signaling pathways (fig. S9). Altogether, this shows a concordance between the ability of second-generation CARs to interact with additional species of CD3ζ and superior CAR-triggered signaling.

Discussion

The implementation of CAR-T cell therapies as a standard treatment highlights the need for a deeper understanding of their mechanism of action. Given the synthetic nature of CARs, and the extensive manipulation that T cells undergo during the manufacturing process, it is plausible that their biochemical activation pathways may be radically different from those of naturally occurring T cells. We first noticed a drastic change in gene expression profiles of T cells transduced with CARs, compared to GFP-transduced counterparts, in a gene expression study. This was indicative of signaling delivered by CARs, even in the absence of antigen recognition. This phenomenon has been termed ‘tonic signaling’, and typically is associated with poor in vivo persistence of CAR-T cells (15, 20, 37). In order to dissect the molecular nature of this signaling, we conducted a comprehensive characterization of the molecules that co-immunoprecipitate with CARs.

We reasoned that molecules present in the vicinity of CARs were more likely to interact, physically or functionally, with them, and that those interactions may explain some of the changes in gene expression that we observed. To that end, we used immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry to get an unbiased view of the proteins that interacted with CARs that contained distinct co-stimulatory domains. The choice of the pull-down reagent was not trivial. Our group has streamlined pull-down strategies based on the use of C-terminus tags in the receptor tyrosine kinase of interest (38). However, for the present study we decided to undertake a different approach: we chose to not use any tag, in order to minimize any biological or biophysical alteration that may introduce technical artifacts and hamper the translational relevance of our results. Moreover, we chose a reagent that binds to the ectodomain of the receptor, instead of the C-terminus, in order to guarantee that the complexes formed in the CAR endodomains remained unperturbed. Finally, we utilized a reagent that can bind any CAR, as long as it contains a kappa-light chain. The versatility contributed by this last aspect allowed for the comparative analysis of CARs containing different antigen-binding domains, using a single reagent. This would be extremely challenging if an anti-idiotype, or any other scFv-specific, reagent were used, because the affinity of each CAR/pull-down reagent would be different, resulting in an additional experimental variable. In order to minimize potential false positives arising from non-specific binding of Protein-L to other antibodies, we washed the cells exhaustively prior to their lysis, and we incorporated a background control of CAR-negative, GFP-expressing T cells. In addition, we filtered the data based on public databases of common contaminants.

Using this immunoproteomic approach, we detected a wide variety of candidate interaction partners, some of which were exclusive to a second-or a third-generation design. For instance, BTNL3, immunoprecipitated only with the second-generation CAR. This butyrophilin-like protein, member of the B7-family, has been implicated in the stimulation of certain subsets of gamma/delta T cells in the human gut (39). Moreover, a genomic deletion resulting in the expression of a BTNL3-BTNL8 fusion protein induced a broad deregulation in the expression of genes relevant to immune function (40). The main limitation of this approach is that it cannot discriminate between direct and indirect interactants. Thus, it is possible that many of the candidate interaction partners identified in this study were not directly bound to the CAR, but rather associated as part of a multiprotein complex. In order to confirm direct protein-protein interactions, a high-resolution method, such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET (41)) would be needed. However, this technique requires the use of fluorescent tags, which may alter the folding and interaction properties of CARs.

We specifically chose to study the 28t28Z design (as a model of second-generation CAR) and the 8t28BBZ design (as a model of third-generation CAR) because of their clinical relevance. The 28t28Z design is the same Kochendender et al. describe in their pioneering work on anti-CD19 CARs (33–35), which is currently commercialized as Yescarta, and in other clinical trials at the National Cancer Institute (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01583686). The third-generation 8t28BBZ design is currently being tested in a clinical trial for gliomas, in the form of an anti-EGFRvIII CAR (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01454596). A comparison of the preclinical performance of these CAR designs is also part of the subject of a study focused on anti-Her2/neu CAR-T cells (42). Further studies will be required to determine which of the CAR interaction partners that we identified are specific to the second-or third-generation CARs designed with different transmembrane and co-stimulatory domains. However, we confirmed that one of the most abundant CAR interaction partners was a CD3ζ-containing protein. We found that CD3ζp21, of slightly greater molecular weight than the endogenous protein, was induced exclusively by expression of second-generation CARs, independently of the transmembrane domain sequence. Moreover, this CD3ζ protein appeared to be spontaneously phosphorylated. First seen by Bridgeman and collaborators, endogenous TCR molecules interact with CARs containing a CD3ζ-derived transmembrane domain (18). In that setting, the CAR-CD3ζ interaction directly associate through an cystine-mediated interchain disulfide bond at position 32 within CD3ζ. This disulfide bond is responsible for the homodimerization of the endogenous CD3ζ molecules, but was not present in any of the CARs that we tested. As a consequence, any interaction between CARs and CD3ζ would have to be established through an alternative residue. Our results also showed that structural properties of the CAR, such as length of the intracellular tail were key for the establishment of tonic signaling through CD3ζ species other than the CAR itself. Although 4–1BB-derived co-stimulatory signaling moiety protects CAR-T cells from the deleterious effects of tonic signaling(20), our results showed that 4–1BB does not prevent spontaneous phosphorylation of the CD3ζ domain built into the CAR, or phosphorylation of CD3ζp21. In addition, Tyr123 phosphorylation in CD3ζp21 appears to be relevant in CAR-T cells expressing PSCA-specific 8tBBZ CAR-T cells. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the cell surface density of the CAR affects its interaction with CD3ζp21, our results indicated that this is not the only determining factor.

We also demonstrated that the second generation PSCA-specific 28t28Z CAR stimulated more intense signaling after antigen recognition, than its third-generation 8t28BBZ counterpart. To test this, we used a variation of the stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) method (36). Similar studies using SILAC in Jurkat cells has identified novel TCR-responsive phosphorylation events (43) and mapped the early (5–60 seconds) tyrosine phosphorylation events downstream of TCR activation (44). Similarly, SILAC on both Jurkat cells and TCR-transgenic mouse T cells indicates histone deacetylases have a role TCR-stimulated serine/threonine phosphorylation (45). In the present study, we performed an exhaustive characterization of the CAR signalosome, focusing exclusively on human primary T cells. This was a conscious decision, in an attempt to maximize the clinical relevance of our findings, and to avoid any species-specific artifact. The choice of a mixed culture system provided realistic antigen stimulation, where the density of PSCA expression resembled that of a real tumor. This experimental design avoided the potential pitfalls of lacking correct target and immune receptor densities (46).

After data acquisition and analysis, we were able to identify 791 phosphorylation events, of which 40 were linked to CAR activity. Several pathways were overrepresented within these CAR-induced phosphorylation events, including TCR, CD28, PKCtheta, STAT3, IL-2, cytokine, and chemokine signaling, among others. Glycolysis and cytoskeleton signaling were also overrepresented. The phosphorylation of ENO1, TPI1, and PKM glycolytic kinases, which are relevant at different stages of the glycolytic pathway, was increased in PSCA-specific second-generation 28t28Z CAR-T cells when compared to GFP-transduced T cells. These data suggest that 28t28Z CARs promote superior activation of glycolysis after CAR stimulation, which may favor an effector memory phenotype(6). In addition, ACTG, FLNA, and RRAS2, which are involved in actin cytoskeleton signaling were differentially phosphorylated in PSCA-specific CAR-T cells. Actin cytoskeleton signaling is crucial for T cell homeostasis and function, in particular for processes that involve active modification of the plasma membrane. RRAS2 has been involved in TCR homeostatic signaling (47), and in internalization of the TCR from the immunological synapse (48), thus linking TCR and cytoskeleton signaling pathways. FLNA, or filamin A induces cytoskeletal rearrangement (49) and accumulation of lipid rafts at the immunological synapse (50) through binding to CD28, also linking together these two signaling pathways.

CD28 phosphorylation was also observed at four different sites: Tyr191, Tyr206, Tyr209, and Tyr218 in CAR-T cells. Some of these sites are well-characterized phosphotyrosine residues necessary for CD28 activity. For example, CD28 pTyr191 promotes PIP3 generation and endocytosis of CD28, and CD28 pTyr209 is involved in production of IL-2 and T cell proliferation (49). We found that CD28 pTyr191 was 10-fold more abundant than that of CD28 pTyr209. In addition, strong CD28 pTyr218 was observed. Although the functional relevance of this phosphosite has not been characterized, given its location at the very C-terminus of wild-type CD28, it is possible that the accessibility of kinases to this site may be affected by the presence of a fused CD3ζ domain in the CAR-bound CD28. Finally, we also detected antigen-induced phosphorylation of CD28 pTyr206. Phosphorylation of this site is also poorly characterized in terms of its functional relevance, and further studies will be needed to elucidate its implications for CAR signaling. These findings highlighted one of the advantages of undertaking a system level approach, as opposed to a more targeted strategy, where these new sites of phosphorylation of the CD28 moiety would have been missed. We found STAT3 was phosphorylated at Tyr705 in CAR-T cells and interacted with the CAR itself. Additionally, the phosphorylation of two other members of the STAT3 canonical pathway was increased in CAR-T cells as well, RRAS2 and MAPK14 (p38). These data suggest that 28t28Z CAR activates STAT3, potentially through CD28-mediated recruitment of LCK (51), and this trait may be relevant to the superior therapeutic efficacy of the 28t28Z CAR(52, 53).

Our data indicated that second-generation CARs activated the signaling pathways analyzed more potently than their third generation counterparts, in contrast to previous reports (54). Although lower signaling potency has been associated with increased CD19-specific CAR-T cell antitumor efficacy (55), our results show that the PSCA-specific 28t28Z CAR that stimulates strong signaling outperforms a 8t28BBZ CAR counterpart displaying qualitatively comparable, but quantitatively weaker signal intensity (14). This discrepancy may indicate that the findings reported by Salter et al. are not universal, but rather specific to either the anti-CD19 CAR, or to the treatment of B-cell malignancies. We theorize that the ability of second generation CARs to engage additional species of CD3ζ in a supramolecular signaling complex may contribute to their superior antitumor capacity. This model is compatible with the results described by Bridgeman and collaborators, showing that certain CARs can mediate signaling through the endogenous CD3ζ (19), suggesting that a functional interaction occurs in addition to the physical interaction. We cannot rule out the possibility that, in some of the phosphosites identified by SILAC, there was an underlying difference in the basal phosphorylation, among CAR-T and control groups. However, the uniform basal phosphorylation of LCK suggests that the differences in phosphorylation of TCR signaling-related proteins following co-culture were antigen-driven. Further studies will be required to determine to what extent this effect will be functionally relevant in CARs containing different scFvs. For instance, CARs containing scFvs with a tendency to aggregate (20) may be affected differently by their interaction with other CD3ζ species than CARs that do not aggregate.

Overall, our results show that the notion of a linear signaling cascade downstream of CAR activation is, at least, incomplete. The challenge for the upcoming years is to fully understand the biology of CAR signaling, in order to have complete control on the molecular events triggered by these synthetic receptors. The modular nature of CARs allows for the integration of multiple signaling pathways and the implementation of intricate strategies to control signaling (56, 57). Understanding the dynamics of CAR-stimulated phosphorylation events as a function of the structural design of these immune receptors will facilitate the furture design of customized artificial phospho-circuits (58) tailored to any desired biological output. We foresee a next generation of CARs that may include specific docking sites for kinases that support tonic signaling and persistence, without causing premature exhaustion. Moreover, we speculate that future CARs may serve as a hub to integrate multiple sensing and signaling functions, including activation, migration, metabolism, and differentiation of T cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and human peripheral blood T cells

HPAC and H2110 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and cultured as recommended. Human primary T cells were obtained from de-identified buffy coats (OneBlood, Florida Blood Services, FL), stimulated ex vivo as previously described (42).

Gene expression analyses

One hundred nanograms of total RNA was amplified and labeled with biotin using the Ambion Message Amp Premier RNA Amplification Kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) following the manufacturer’s protocol initially described by Van Gelder et al. (59). Hybridization with the biotin-labeled RNA, staining, and scanning of the chips followed the prescribed procedure outlined in the Affymetrix technical manual and has been previously described (60). The oligonucleotide probe arrays used were the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Arrays, which contain over 54,000 probe sets representing over 47,000 transcripts. The array output files were visually inspected for hybridization artifacts and then analyzed using Affymetrix Expression Console v 1.4 using the MAS 5.0 algorithm, scaling probe sets to an average intensity of 500.

Retroviral vectors and cell transduction

Retroviral supernatants encoding chimeric antigen receptors were generated using the 293GP cell system, as previously described (14). For simplification, the Ha1–4.117–28Z and Ha1–4.117–28BBZ CARs (14) were referred to as PSCA-28t28Z and PSCA-8t28BBZ in the present manuscript. PSCA-28t28BBZ contains the same transmembrane and hinge domain as PSCA-28t28Z, followed by cytoplasmic tail of PSCA-8t28BBZ. PSCA-8t28Z contains the same hinge and transmembrane domain as PSCA-8t28BBZ, followed by the cytoplasmic tail of PSCA-28t28Z. PSCA-8tBBZ is composed of the same sequence as PSCA-8t28BBZ, minus the CD28 intracellular moiety. Anti-Her2/neu CARs were generated by replacing the scFv portion of the anti-PSCA CARs with the scFv cDNA of the Herceptin-derived CARs described by Zhao et al. (42). Transduction of T cells with RD114-pseudotyped retroviral vectors was performed on days 2 and 3 post-CD3 stimulation, as previously described (61).

CAR interactome using Mass Spectrometry

Anti-PSCA CARs were used as baits to immunoprecipitate interacting partners, which were eluted with 6X Laemmli sample buffer. Immunoprecipitation was performed 14 days after retroviral transduction. Briefly, 20 × 106 CAR-T cells (or GFP controls), including both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, were pelleted and washed thoroughly with PBS. Protein extracts were then prepared using an NP-40-based lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, 0.5% NP-40, 100 mM NaCl, 15mM EDTA pH=8.0), supplemented with protease (Roche, #04693116001) and phosphatase (Sigma, #P0044) inhibitors, following the manufacturers’ instructions. Samples were sonicated using a Bioruptor™ (Diagenode, 3× 8 pulses of 30 seconds, with 30 seconds of rest time, at 20 KHz). Samples were then centrifuged at maximum speed in a microcentrifuge at 4°C, for 45 minutes. Supernatants were used for immunoprecipitation. Protein-L Magnetic beads (Pierce™, #88849) were washed twice with lysis buffer, and then added to the protein extracts. The mixture was incubated for 4 h or overnight at 4°C, in a rotator mixer. Immunocomplexes were then recovered using a DynaMag™−2 magnet (Life Technologies, #12321D). After 3 washes with lysis buffer, immunoprecipitated samples were processed for SDS-PAGE. Three biological replicates were prepared for each second generation CAR (PSCA-28t28Z), third generation CAR (PSCA-8t28BBZ), or GFP-transduced controls. Samples were reduced with XT reducing agent (Bio-Rad) and heated at 95°C for 5 min. Sample were run on a 10% Bis-Tris gel at 150 V for 10 min. The stacked gel bands from each lane were excised, reduced with 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) and alkylated with 20 mM iodoacetamide. Proteins in each gel band were enzymatically digested with 600 ng trypsin overnight at 37 °C. The peptide mixture from each sample was dried in a vacuum centrifuge and re-suspended in 2% acetonitrile containing 0.1% FA.

The peptide mixtures were analyzed using nanoflow liquid chromatography (RSLC, Dionex) coupled to a hybrid quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (QExactive Plus, ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.) in a data-dependent manner for tandem mass spectrometry peptide sequencing. Peptide mixtures were separated on a 75 µm × 25 cm C18 column (New Objective, Woburn, MA) using a 70 min linear gradient of 5–38.5% B over 90 min with a flow rate of 300 nL/min (Ultimate, Dionex). Solvent A was composed of aqueous 2% acetonitrile containing 0.1% FA. Solvent B was 90% acetonitrile and 10% HPLC grade H2O containing 0.1% FA. Data analysis was performed using MASCOT and SEQUEST, and the Human UniProt database was modified to include the CAR sequences. Both MASCOT and SEQUEST search results were summarized in Scaffold 4.3.4 (Proteome Software, http://www.proteomesoftware.com). The relative quantification of peptides was calculated using MaxQuant (version 1.2.2.5). Peaks were searched against the Human entries in the UniProt database (20,151 sequences, including the CAR sequence; released August 2015) with the Andromeda search engine (62). The raw files were processed with the following parameters: including > 7 amino acids per peptide, as many as three missed cleavages, and a false discovery rate of 0.01 was selected for peptides and proteins. Methionine oxidation and peptide N-terminal acetylation were selected as variable modifications in protein quantification. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine and methionine oxidation were selected as variable modifications. Following protein identification and relative quantification with MaxQuant, the data were normalized using iterative rank order normalization (IRON) (63) and imported into Galaxy (64–66) for analysis with the affinity proteomics analysis tool, APOSTL (http://apostl.moffitt.org) (67). The data was pre-processed into inter, bait and prey files and analyzed by SAINTexpress (68) and checked against the CRAPome (69) within APOSTL. SAINTexpress results were further filtered (SaintScore > 0.8), processed and analyzed in APOSTL’s interactive environment. Following APOSTL analysis, the data was filtered (MaxP > 0.8) to capture the maximum amount of interactions for STRING network analysis (confidence > 0.9).

Tyrosine-phosphorylated peptide pull down, IMAC enrichment, LC-MS/MS, and data analysis

Briefly, 40 × 106 cells (20 × 106 HPAC cells, plus 20 × 106 CAR-T cells, including CD8+ and CD4+ populations) were lysed in denaturing lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate and 1 mM β-glycerophosphate. The proteins were reduced with 4.5 mM DTT and alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide. Trypsin digestion (enzyme-to-substrate ratio 1:20 w/w) was carried out at room temperature overnight, and tryptic peptides were then acidified with 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and desalted with C18 cartridges according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sep-Pak, Waters). Following lyophilization, the dried peptide pellet was re-dissolved in immunoaffinity purification (IAP) buffer containing 50 mM MOPS pH 7.2, 10 mM sodium phosphate and 50 mM sodium chloride. Phosphotyrosine-containing peptides were immunoprecipitated with immobilized anti-phosphotyrosine antibody p-Tyr-1000 (Cell Signaling Technology). After overnight incubation, the antibody beads were washed 3 times with IAP buffer, followed by 2 washes with deionized H2O. The phosphotyrosine peptides were eluted twice with 0.15% TFA, and the volume was reduced to 20 µl via vacuum centrifugation.

The remaining peptides from pY enrichment were extracted using SepPak C18 cartridges and re-dissolved in IMAC binding buffer containing 1% aqueous acetic acid and 30% acetonitrile. The phosphopeptides in each fraction were enriched using IMAC resin (PHOS-Select™ Iron Affinity Gel, Sigma). Briefly, the IMAC resin was washed twice with binding buffer. The peptides were incubated with the IMAC resin for 30 min at room temperature, with gentle agitation every 5 minutes. Ten microliters of IMAC resin (20 microliters of slurry) was added per milligram of starting material. After incubation, the IMAC resin was washed twice with wash buffer 1 (aqueous 0.1% acetic acid and 100 mM NaCl, pH 3.0), followed by 2 washes with wash buffer 2 (aqueous 30% ACN, 0.1% acetic acid, pH 3.0) and 1 wash with H2O. The phosphopeptides were eluted with elution buffer (containing 20% ACN, 200 mM Ammonium Hydroxide). The volume was reduced to 20 µl via vacuum centrifugation.

A nanoflow ultra-high performance liquid chromatograph (RSLC, Dionex) interfaced with an electrospray bench top quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (QExactive Plus, Thermo, San Jose, CA) was used for tandem mass spectrometry peptide sequencing and relative quantification. The sample was first loaded onto a trapping column (2 cm x 100 µm ID packed with C18 reversed-phase resin, 5µm, 100Å) and washed for 8 minutes with aqueous 2% acetonitrile and 0.04% TFA. The trapped peptides were eluted onto the analytical column, (C18, 75 µm ID x 25 cm, 2 µm particle size, 100Å pore size, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA). The 90-minute gradient was programmed as: 95% solvent A (as above or aqueous 2% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid) for 8 minutes, solvent B (as above or aqueous 90% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid) from 5% to 38.5% in 60 minutes, then solvent B from 50% to 90% B in 7 minutes and held at 90% for 5 minutes, followed by solvent B from 90% to 5% in 1 minute and re-equilibration for 10 minutes. The flow rate on analytical column was 300 nl/min. Sixteen tandem mass spectra were collected in a data-dependent manner following each survey scan. MS/MS scans were performed using 60 second exclusion for previously sampled peptide peaks.

Sequest (70) and Mascot (71) searches were performed against the UniProt human database. Two trypsin missed cleavages were allowed, the precursor mass tolerance was 20 ppm. MS/MS mass tolerance was 0.05 Da. Dynamic modifications included carbamidomethylation (Cys), oxidation (Met), phosphorylation (STY) and SILAC labeling (K/R). Both MASCOT and SEQUEST search results were summarized in Scaffold 4.4. MaxQuant (72) (version 1.2.2.5) and Skyline (MacCoss Lab Software, University of Washington) (73) were used to quantify the relative peptide intensities.

CD3ζ Phosphorylation Analysis by LC-MS/MS

For analysis of CD3ζ phosphorylation in PSCA-8tBBZ samples, total CD3ζ was immunoprecipitated using a mouse monoclonal anti-CD3ζ antibody (F3, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) and Protein G beads (Millipore) following the protocol provided by the Santa Cruz Biotechnologies. Immunoprecipitates were then separated by SDS-PAGE. A gel slice ranging from 21 to 25kDa was excised and digested, as described above for CAR interactome studies. LC-MS/MS was performed as described above; to maximize the ability to detect specific peptides, parallel reaction monitoring (or targeted MS/MS) was programmed for the expected charge states of phosphopeptides that had been previously observed in our data or reported in the literature. Sequest and Mascot database searches were used to identify phosphorylated peptides that were manually verified by inspection of mass measurement accuracy and fragment ion matching in the tandem mass spectra. MS/MS spectrum of peptide GHDGLYQGLSTATK: pTyr142 was located by b5 and b6 ions, because the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of the b6 ion indicates the inclusion of the phosphorylation. Sequest XCorr sc score 2.62 and ∆CN score 0.71. MS/MS spectrum of peptide MAEAYSEIGMK: pTyr123 was located by y6 and y7 ions, because the m/z of y7 ion indicates the presence of the phosphorylation. Sequest XCorr score 2.60 and ∆CN score 0.74.

Bioinformatic analyses

Gene expression analyses including hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) were conducted using Partek Genomic Suite (Partek Incorporated, St. Louis, MO). Pathway identification was performed with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, Qiagen). Expression data was normalized using IRON (63) and log2 transformed. For group-wise comparisons a Student t-test was used and a FDR (74) corrected p-value < 0.01 with log2 mean |FC| > 1 was consider significant. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using the http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/ querying the HALLMARK gene sets(75). These statistical tests and figures were generated using MATLAB 9.2 and Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox 11.1, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States. For interactome and signalosome analyses, a user-generated list of proteins was used as reference population, including only proteins that were detected by mass spectrometry in at least one of the samples. For network analysis, high confidence CAR interactions (SaintScore > 0.8) and significantly altered phosphosites were used to generate a network (STRING). Topological modules were identified using fast-greedy community optimization(76) and module function was determined using clusterProfiler (77) and visual inspection. Kinase-substrate predictions were done using NetworKIN (78) (http://networkin.info/).

Western blot

Protein content was quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay (Fisher Cat. #PI23227) and protein content was equalized across samples before treatment with laemmli buffer. The samples were then loaded onto a 4–15% gradient gel, ran at 80V, and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using the Trans-Blot® Turbo System. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature on a rocker (5 % milk or BSA in 1× PBS-0.1 % TWEEN 20). After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C on a rocker with appropriate concentration of primary antibodies against CD3ζ (F3) (Santa Cruz, Cat.# SC-166275), ACTB, GAPDH (Santa Cruz, Cat.# SC-25778), BTNL3 (Abcam, Cat.# ab177473), p-CD3ζ (Tyr72) (Sigma Cat.# SAB4200330), p-CD3ζ (Tyr83) (Abcam, Cat. # ab68236), and p-CD3ζ (Tyr142) (Abcam, Cat.# ab68236), p-LCK (Tyr192) (Abcam, Cat. #138524) or (Tyr505) (Cell Signaling Cat. #2751), and LCK (Cell Signaling Cat. #2752). The next day, the membranes were washed three times for 10 min in 1× PBS–0.1 % Tween 20 and incubated with appropriate secondary in 5 % blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature on a rocker. Bands were detected by immunofluorescent secondary antibodies, Goat anti rabbit 680LT (Li-Cor, Cat.# 926–68021) and Goat anti mouse 800CW (Li-Cor, Cat.# 926–32210). Wash three times for 10 min in 1× PBS–Tween 20. Dry the membrane between filter paper, making sure to protect against the light with foil. Membranes were developed by scanning blots with LI2COR Odyssey imaging system using both 700 and 800 channels.

Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions were stained with monoclonal Abs against human: CD3 BV421, CD8 BUV396, CD25 BUV737, CD69 PE and BTLA BV650 (all from BD). CD3 AlexaFluor700, LAG-3 APCeFluor780, CD152 (CTLA4) PECy7, and CD122 BV421 (all from Biolegend). TIGIT PerCPeFluor710 and PD-1 PE (from eBioscience), F(ab) Alexa Fluor 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and Tim-3 PE (R&D). CAR expression on transduced lymphocytes was detected by using biotinylated Protein L (GenScript) and a secondary incubation with Streptavidin PE (Biolegend). Dead cells were excluded based on staining with Live/Dead Yellow fixable dye (eBioscience) or DAPI (BD). For proliferation assays, GFP and CAR-T cells were stained with CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen, C34557, final concentration: 2uM) following manufacturer’s instructions. The staining was analyzed at day 0 by flow cytometry and then, the cells were cultured during 72 hours in T-cell expansion media (X-VIVO media supplemented with AB human serum plus IL-2) without further stimulation. Then, cells were collected and stained at surface with anti-CD3 and anti-Fab antibodies. 7-AAD (Invitrogen) was used to exclude dead cells. For phospho-flow staining experiments, unstimulated GFP-or CAR-T cells (day 14) were first stained with Live/Dead Yellow dye and then surface stained with anti-CD3 and anti-F(ab) antibodies for 20 min in ice. Then stained cells were fixed with Lyse-Fix buffer (BD) for 10 min at 37°C, washed and permeabilized with Perm Buffer III (BD) for 20 min on ice. Cells were next intracellularly stained with anti-phospho CD3ζ Alexa Fluor 647 (Tyr142, Clone: K25–407.6, BD Phosflow) or antibodies against total CD3ζ PE (as control, ImmunoTech) for 30 min at room temperature. All samples were acquired using a BD FACSCanto II or a BD LSRII flow cytometers (BD Biosciences) and data analyzed with FlowJo software.

ELISA assays

IFNγ were measured by ELISA (Biolegend and Thermo Fisher Scientific, respectively) in co-culture supernatants after overnight incubation of CAR-T or GFP-transduced T cells (100000 effectors/well) with PSCA+ and PSCA- tumor cell lines (100000 target/well) or in absence of tumor cells.

Mouse studies

All animal studies were performed in compliance with institutional regulations on animal use. Procedures were approved by the University of South Florida IACUC (protocol R IS00002385). Experiments were performed in the Comparative Medicine Facility, following the protocol described previously (14). Briefly, 4-/5-week-old male NSG mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Subcutaneous xenografts were genererated by injection of HPAC cells (2 × 106 per mouse). Once tumors became palpable, mice were treated with CD8 T cells expressing either GFP, PSCA-28t28Z or PSCA-8t28BBZ. Untransduced CD4 cells from the same donor were given to each mouse for cytokine support. For gene expression and phenotypic analysis, 3 mice were treated per group. Pre-infusion lymphocytes were stored at the moment of treatment, this is, 2 weeks post-transduction. For isolation of post-infusion CD8+ T cells, spleens were harvested and processed using the CD8 MicroBeads (human, Miltenyi Biotech).

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Gene expression analysis of CD8+ CAR-T cells pre-and post-adoptive cell transfer

Fig. S2. CAR-expressing cells exhibit an activated phenotype.

Fig. S3. CAR interactome.

Fig. S4. CARs interact with multiple endogenous proteins.

Fig. S5. CAR expression induces spontaneous phosphorylation of ZAP70 and CD3ζ.

Fig. S6. CAR endodomain is responsible for interaction with CD3ζ.

Fig. S7. Integrated network of CAR interactome and CAR signaling upon antigen binding.

Fig. S8. Second-generation CARs modulate proximal TCR signaling, glycolytic metabolism and actin reorganization to greater extent than third-generation CARs.

Fig. S9. CD28, STAT3 and p38 signaling pathways are activated by second-generation CAR-T cells.

Fig. S10. LCK basal phosphorylation in CAR-T cells is equivalent.

Fig. S11. Predicted kinase substrate interactions for CD3ζ and CD28

Table S1. Candidate interaction partners.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Dr. James Mulé and Dr. José Conejo-Garcia for critical review of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Shari Pilon-Thomas who contributed reagents.

Funding: BMK was a recipient of the NIH/NCI F99/K00 Predoctoral to Postdoctoral Transition Award F99 CA212456. MPS was a recipient of a T32 training grant (CA147832), DS was a recipient of a T32 training grant (CA115308). This work has been supported in part by the Proteomics, Molecular Genomics, and Flow Cytometry Core Facilities at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute; an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292). This study was partially funded by a grant from Moffitt’s Lung Cancer Center of Excellence, Immuno-Oncology Group.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science Signaling. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencesignaling.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.

Competing interests: DAD is listed as inventor or co-inventor in CAR-related provisional patent applications filed by Moffitt Cancer Center (PCT/US17/65249; PCT/US2018/019147; 62/643,908; 62/677,738; 62/683,792; 62/715,504) and is a member of Anixa Biosciences’ scientific advisory board.

Data and materials availability: The gene expression data have been deposited to the NCBI GEO database with the dataset identifier GSE102823. The mass spectrometry data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium through the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifiers PXD007085 (interactome) and PXD007086 (signalosome). All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References and Notes:

- 1.Abate-Daga D, Davila ML, CAR models: next-generation CAR modifications for enhanced T-cell function. Mol Ther Oncolytics 3, 16014 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown CE, Alizadeh D, Starr R, Weng L, Wagner JR, Naranjo A, Ostberg JR, Blanchard MS, Kilpatrick J, Simpson J, Kurien A, Priceman SJ, Wang X, Harshbarger TL, D’Apuzzo M, Ressler JA, Jensen MC, Barish ME, Chen M, Portnow J, Forman SJ, Badie B, Regression of Glioblastoma after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. N Engl J Med 375, 2561–2569 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown CE, Starr R, Aguilar B, Shami AF, Martinez C, D’Apuzzo M, Barish ME, Forman SJ, Jensen MC, Stem-like tumor-initiating cells isolated from IL13Ralpha2 expressing gliomas are targeted and killed by IL13-zetakine-redirected T Cells. Clin Cancer Res 18, 2199–2209 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross G, Gorochov G, Waks T, Eshhar Z, Generation of effector T cells expressing chimeric T cell receptor with antibody type-specificity. Transplant Proc 21, 127–130 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finney HM, Lawson AD, Bebbington CR, Weir AN, Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signaling in T cells from a single gene product. J Immunol 161, 2791–2797 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawalekar OU, O’Connor RS, Fraietta JA, Guo L, McGettigan SE, Posey AD Jr., Patel PR, Guedan S, Scholler J, Keith B, Snyder NW, Blair IA, Milone MC, June CH, Distinct Signaling of Coreceptors Regulates Specific Metabolism Pathways and Impacts Memory Development in CAR T Cells. Immunity 44, 380–390 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guedan S, Chen X, Madar A, Carpenito C, McGettigan SE, Frigault MJ, Lee J, Posey AD Jr., Scholler J, Scholler N, Bonneau R, June CH, ICOS-based chimeric antigen receptors program bipolar TH17/TH1 cells. Blood 124, 1070–1080 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song DG, Ye Q, Poussin M, Harms GM, Figini M, Powell DJ Jr., CD27 costimulation augments the survival and antitumor activity of redirected human T cells in vivo. Blood 119, 696–706 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hombach AA, Heiders J, Foppe M, Chmielewski M, Abken H, OX40 costimulation by a chimeric antigen receptor abrogates CD28 and IL-2 induced IL-10 secretion by redirected CD4(+) T cells. Oncoimmunology 1, 458–466 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowolik CM, Topp MS, Gonzalez S, Pfeiffer T, Olivares S, Gonzalez N, Smith DD, Forman SJ, Jensen MC, Cooper LJ, CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res 66, 10995–11004 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tammana S, Huang X, Wong M, Milone MC, Ma L, Levine BL, June CH, Wagner JE, Blazar BR, Zhou X, 4–1BB and CD28 signaling plays a synergistic role in redirecting umbilical cord blood T cells against B-cell malignancies. Hum Gene Ther 21, 75–86 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen CJ, Yang YX, Han EQ, Cao N, Wang YF, Wang Y, Zhao YY, Zhao LM, Cui J, Gupta P, Wong AJ, Han SY, Chimeric antigen receptor containing ICOS signaling domain mediates specific and efficient antitumor effect of T cells against EGFRvIII expressing glioma. J Hematol Oncol 6, 33 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duong CP, Westwood JA, Yong CS, Murphy A, Devaud C, John LB, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH, Engineering T cell function using chimeric antigen receptors identified using a DNA library approach. PLoS One 8, e63037 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abate-Daga D, Lagisetty KH, Tran E, Zheng Z, Gattinoni L, Yu Z, Burns WR, Miermont AM, Teper Y, Rudloff U, Restifo NP, Feldman SA, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA, A novel chimeric antigen receptor against prostate stem cell antigen mediates tumor destruction in a humanized mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Hum Gene Ther 25, 1003–1012 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe N, Bajgain P, Sukumaran S, Ansari S, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Brenner MK, Leen AM, Vera JF, Fine-tuning the CAR spacer improves T-cell potency. Oncoimmunology 5, e1253656 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alabanza L, Pegues M, Geldres C, Shi V, Wiltzius JJW, Sievers SA, Yang S, Kochenderfer JN, Function of Novel Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptors with Human Variable Regions Is Affected by Hinge and Transmembrane Domains. Mol Ther, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Yokosuka T, Saito T, The immunological synapse, TCR microclusters, and T cell activation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 340, 81–107 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bridgeman JS, Hawkins RE, Bagley S, Blaylock M, Holland M, Gilham DE, The optimal antigen response of chimeric antigen receptors harboring the CD3zeta transmembrane domain is dependent upon incorporation of the receptor into the endogenous TCR/CD3 complex. J Immunol 184, 6938–6949 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bridgeman JS, Ladell K, Sheard VE, Miners K, Hawkins RE, Price DA, Gilham DE, CD3zeta-based chimeric antigen receptors mediate T cell activation via cis-and trans-signalling mechanisms: implications for optimization of receptor structure for adoptive cell therapy. Clin Exp Immunol 175, 258–267 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long AH, Haso WM, Shern JF, Wanhainen KM, Murgai M, Ingaramo M, Smith JP, Walker AJ, Kohler ME, Venkateshwara VR, Kaplan RN, Patterson GH, Fry TJ, Orentas RJ, Mackall CL, 4–1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Med 21, 581–590 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argani P, Rosty C, Reiter RE, Wilentz RE, Murugesan SR, Leach SD, Ryu B, Skinner HG, Goggins M, Jaffee EM, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Kern SE, Hruban RH, Discovery of new markers of cancer through serial analysis of gene expression: prostate stem cell antigen is overexpressed in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 61, 4320–4324 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amara N, Palapattu GS, Schrage M, Gu Z, Thomas GV, Dorey F, Said J, Reiter RE, Prostate stem cell antigen is overexpressed in human transitional cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 61, 4660–4665 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei X, Lai Y, Li J, Qin L, Xu Y, Zhao R, Li B, Lin S, Wang S, Wu Q, Liang Q, Peng M, Yu F, Li Y, Zhang X, Wu Y, Liu P, Pei D, Yao Y, Li P, PSCA and MUC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer as targets of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Oncoimmunology 6, e1284722 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiter RE, Gu Z, Watabe T, Thomas G, Szigeti K, Davis E, Wahl M, Nisitani S, Yamashiro J, Le Beau MM, Loda M, Witte ON, Prostate stem cell antigen: a cell surface marker overexpressed in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 1735–1740 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramello MC, Haura EB, Abate-Daga D, CAR-T cells and combination therapies: What’s next in the immunotherapy revolution? Pharmacol Res 129, 194–203 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abate-Daga D, Hanada K, Davis JL, Yang JC, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA, Expression profiling of TCR-engineered T cells demonstrates overexpression of multiple inhibitory receptors in persisting lymphocytes. Blood 122, 1399–1410 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Z, Chinnasamy N, Morgan RA, Protein L: a novel reagent for the detection of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) expression by flow cytometry. J Transl Med 10, 29 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zybailov B, Mosley AL, Sardiu ME, Coleman MK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Statistical analysis of membrane proteome expression changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteome Res 5, 2339–2347 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan AC, Irving BA, Fraser JD, Weiss A, The zeta chain is associated with a tyrosine kinase and upon T-cell antigen receptor stimulation associates with ZAP-70, a 70-kDa tyrosine phosphoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88, 9166–9170 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monostori E, Desai D, Brown MH, Cantrell DA, Crumpton MJ, Activation of human T lymphocytes via the CD2 antigen results in tyrosine phosphorylation of T cell antigen receptor zeta-chains. J Immunol 144, 1010–1014 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Presotto D, Erdes E, Duong MN, Allard M, Regamey PO, Quadroni M, Doucey MA, Rufer N, Hebeisen M, Fine-Tuning of Optimal TCR Signaling in Tumor-Redirected CD8 T Cells by Distinct TCR Affinity-Mediated Mechanisms. Front Immunol 8, 1564 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinberg M, Adjali O, Swainson L, Merida P, Di Bartolo V, Pelletier L, Taylor N, Noraz N, T-cell receptor-induced phosphorylation of the zeta chain is efficiently promoted by ZAP-70 but not Syk. Blood 104, 760–767 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kochenderfer JN, Feldman SA, Zhao Y, Xu H, Black MA, Morgan RA, Wilson WH, Rosenberg SA, Construction and preclinical evaluation of an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Immunother 32, 689–702 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kochenderfer JN, Wilson WH, Janik JE, Dudley ME, Stetler-Stevenson M, Feldman SA, Maric I, Raffeld M, Nathan DA, Lanier BJ, Morgan RA, Rosenberg SA, Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood 116, 4099–4102 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, Wilson WH, Spaner DE, Maric I, Stetler-Stevenson M, Phan GQ, Hughes MS, Sherry RM, Yang JC, Kammula US, Devillier L, Carpenter R, Nathan DA, Morgan RA, Laurencot C, Rosenberg SA, B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 119, 2709–2720 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ong SE, Kratchmarova I, Mann M, Properties of 13C-substituted arginine in stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC). J Proteome Res 2, 173–181 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommermeyer D, Hill T, Shamah SM, Salter AI, Chen Y, Mohler KM, Riddell SR, Fully human CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptors for T-cell therapy. Leukemia, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Haura EB, Muller A, Breitwieser FP, Li J, Grebien F, Colinge J, Bennett KL, Using iTRAQ combined with tandem affinity purification to enhance low-abundance proteins associated with somatically mutated EGFR core complexes in lung cancer. J Proteome Res 10, 182–190 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Marco Barros R, Roberts NA, Dart RJ, Vantourout P, Jandke A, Nussbaumer O, Deban L, Cipolat S, Hart R, Iannitto ML, Laing A, Spencer-Dene B, East P, Gibbons D, Irving PM, Pereira P, Steinhoff U, Hayday A, Epithelia Use Butyrophilin-like Molecules to Shape Organ-Specific gammadelta T Cell Compartments. Cell 167, 203–218 e217 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aigner J, Villatoro S, Rabionet R, Roquer J, Jimenez-Conde J, Marti E, Estivill X, A common 56-kilobase deletion in a primate-specific segmental duplication creates a novel butyrophilin-like protein. BMC Genet 14, 61 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]