Abstract

Frontal sinus fractures are an uncommon injury of the maxillofacial skeleton, and account for 5–15% of all maxillofacial fractures. As the force of impact increases, fractures may extend beyond the anterior table to involve adjacent skull, posterior table and frontal sinus outflow tract (FSOT). Fractures at these subsites should be evaluated independently to assess the need for and type of operative intervention. Historically, these fractures were managed aggressively with open techniques resulting in obliteration or cranialization. With significant injuries, these approaches are still indispensable. However, the treatment of frontal sinus fractures has changed dramatically over the past half-century, and recent case series have demonstrated favorable outcomes with conservative management. Concurrently, there has been an increasing role of minimally invasive endoscopic techniques, both for primary and expectant management, with a focus on sinus preservation. Here, we review the diagnosis and management of frontal sinus fractures, with an emphasis on subsite evaluation. Following a detailed assessment, an appropriate treatment strategy is selected from a variety of open and minimally invasive approaches available in the surgeon's armamentarium.

Keywords: frontal sinus, minimally invasive, frontal sinus outflow tract, frontal sinus fractures, endoscopic sinus surgery

Frontal sinus fractures account for 5–15% of maxillofacial injuries. 1 2 3 4 Being a midline, aerated space in the upper third of the facial skeleton, the frontal sinus is thought to act as a “crumple zone,” protecting the inner cranial vault. 5 6 7 The force required to fracture the dome shaped anterior table is substantial ranging from 800–2200 pounds. 8 As the force of impact to the frontal sinus increases, fractures may extend beyond the anterior table to involve adjacent skull, posterior table and frontal sinus outflow tract (FSOT). Fractures at these subsites should be evaluated independently to assess the need for and type of operative intervention. Typically, fractures of the anterior table are repaired to correct a cosmetic deformity, while fractures of the posterior table are repaired to prevent intracranial complications including cerebrospinal fluid leak, meningitis, mucocele or brain abscess. Finally, operative intervention for FSOT injuries aims at preventing delayed complications of frontal sinusitis, mucocele, or mucopyocele. After assessing these injuries, a surgical approach and strategy can be formulated. There is a current trend toward conservative and endoscopic management of all aspects of frontal sinus fractures.

Anatomy

Development of the paranasal sinuses, including the frontal sinus, begins at the 4 th week of gestation and continues into young adulthood. During the 9 th and 10 th week, medial extensions of the nasal cavity, the ethmoturbinals, form important surgical landmarks as well as the frontal sinus outflow tract. Primary pneumatization of the frontal sinus is a slow process, occurring through the first year of life as a blind pocket. Secondary pneumatization starts around age two and continues through adolescence. The frontal sinus is identifiable on CT imaging around age 3. Significant pneumatization does not begin until early adolescence, and finishes around age 18. 9 The right and left frontal sinus develop independently, separated by an intersinus septum. 10 Aplasia of one or both frontal sinuses is uncommon, seen in 1–8% of the population. 11 12 Race, craniofacial anomalies, geography, climate, and hormones have all been implicated in affecting frontal sinus development. 10

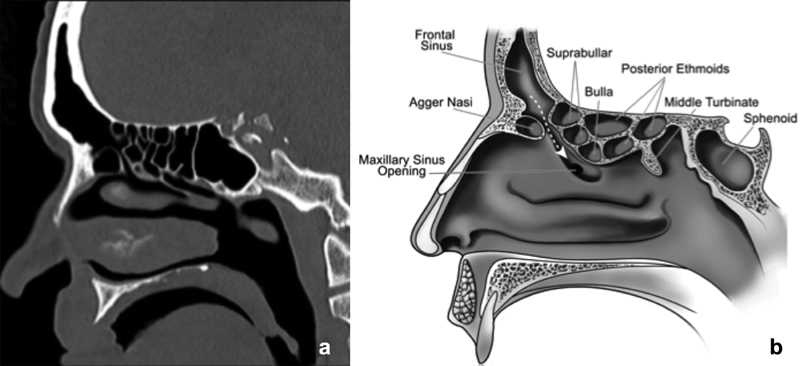

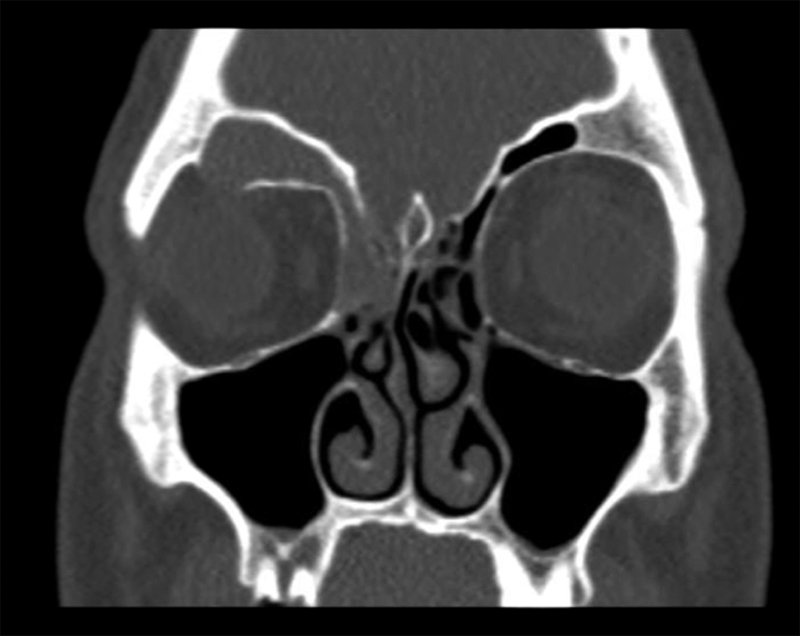

The frontal sinus outflow tract (FSOT) is an hourglass shape, made up of the infundibulum superiorly, the frontal recess inferiorly, and separated by the ostium or narrowest portion (3–4 mm). There are a variety of pneumatization patterns of ethmoidal cells that are adjacent to the FSOT. 13 The FSOT is found in the posterior, inferior, and medial portion of the frontal sinus. ( Fig. 1 )

Fig. 1.

(a) CT in the sagittal plane of the frontal sinus outflow tract (FSOT). (b) Corresponding illustration of the frontal sinus outflow tract (dotted arrow) bordered anteriorly by the agger nasi cell and posteriorly by the suprabullar and bullar cells.

The anterior table of the frontal sinus is thick (2–12 mm) and forms part of the brow, glabela, and forehead. Skin, subcutaneous tissue, the frontalis muscle (corrugator), and vascularized pericranium overlie the anterior table. The posterior table is thin (0.1–4 mm) and penetrated by microscopic vessels via the foramina of Breschet. The thinness and foramina risk infection transmission and erosion from inflammatory conditions such as mucopyoceles. The posterior table forms a portion of the anteroinferior border of the anterior cranial fossa and cribriform plate. It has a superior, vertical portion along with a smaller, inferior horizontal portion. The posterior table is separated from the frontal lobes only by dura. The floor comprises the medial portion of the orbital roof and can be confused with supraorbital ethmoid cells when these are highly pneumatized. The height of the frontal sinus averages 28–30 mm, with a width and depth of 20 mm, forming a space of 5–7 mL. 14 The superior sagittal sinus typically travels along posterior to the intersinus septum and anterior to the crista gali, which are continuous with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid inferiorly. The vascular supply includes terminal branches of the sphenopalatine artery ascending superiorly as well as the terminal branches of the ophthalmic artery including the supraorbital, supratrochlear, and anterior ethmoid arteries. Venous drainage occurs via valveless diploic veins with intracranial communication. Branches of the trigeminal nerve provide sensory innervation.

Evaluation

As in all patients presenting with trauma, a systematic assessment should be performed with initial focus on airway control, hemodynamic stability and mitigation of neurologic injury. Secondary evaluation should include a complete physical exam. Patients with frontal trauma may present with soft tissue injuries including abrasions, lacerations, and hematomas. Fractures of the frontal sinus may also present with contour deformities, diplopia, paresthesia, epistaxis, and rhinorrhea. In initial evaluation of these wounds, exploration should be limited given the possibility of posterior table or nasoorbitoethmoid involvement. While not usually an immediate concern unless there is a CSF leak, patients may also have olfactory disturbance secondary to shearing of olfactory neurons at the cribriform plate. 15

Once stabilized, thin-cut CT imaging is essential to evaluating fractures of the frontal sinus. Axial cuts delineate fractures of the anterior and posterior tables with corresponding displacement or comminution. In the presence of posterior table fractures, any opacification on imaging may represent CSF or brain herniation. Reconstructions in the sagittal and coronal planes aid in visualizing the 3D anatomy of the sinus floor and FSOT. The anterior and posterior tables along with the FSOT should be examined independently to guide further management.

Anterior Fractures

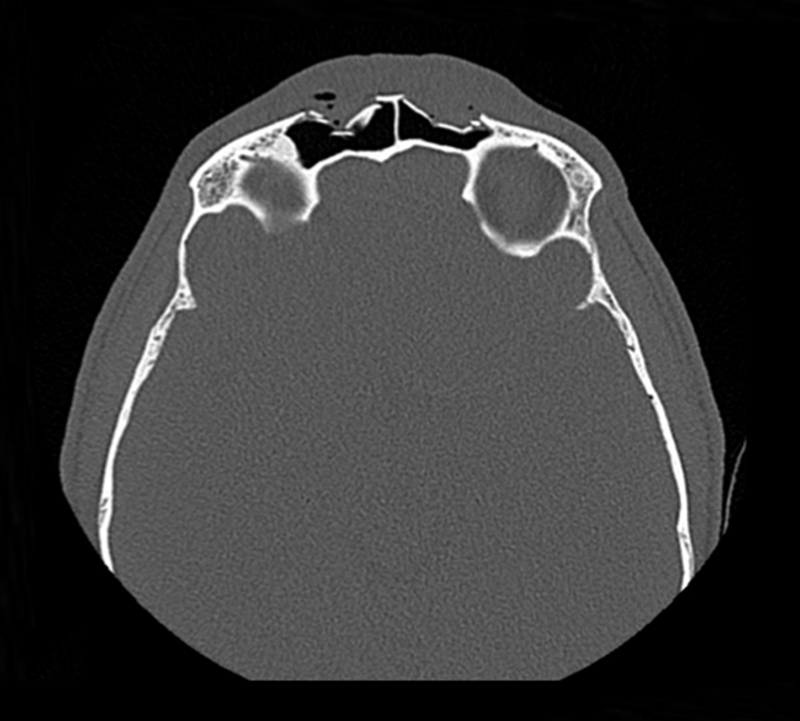

Fractures isolated to the anterior table account for 18–27% of frontal sinus fractures. 3 5 16 The indication for repair has mainly focused on correcting a cosmetic deformity. Without injury to the frontal sinus outflow tract or posterior table, many series have reported on the safety of observation of isolated anterior table fractures. 1 3 4 17 18 The degree of displacement necessitating repair is controversial. The degree of displacement seen on CT imaging may not correlate with the either the visualized or palpated deformity due to overlying edematous soft tissue. It is also difficult to predict the degree of resultant deformity after the acute swelling subsides ( Fig. 2 ). Furthermore, physician and patient expectations vary regarding the definition of an “acceptable” forehead contour. With observation, bony remodeling and scarring over an intact periosteum may subsequently hide any cosmetic deformity, especially in pediatric patients. 19

Fig. 2.

CT in the axial plane demonstrating a comminuted, displaced bilateral fracture of the anterior table of the frontal sinus fracture. In the acute setting, significant soft tissue edema may obscure a palpable deformity.

To correct an anterior deformity, there are a variety of approaches to the anterior table of the frontal sinus. Selection of the appropriate technique depends on the degree of fracture displacement and comminution, cosmetic concerns, and surgeon experience.

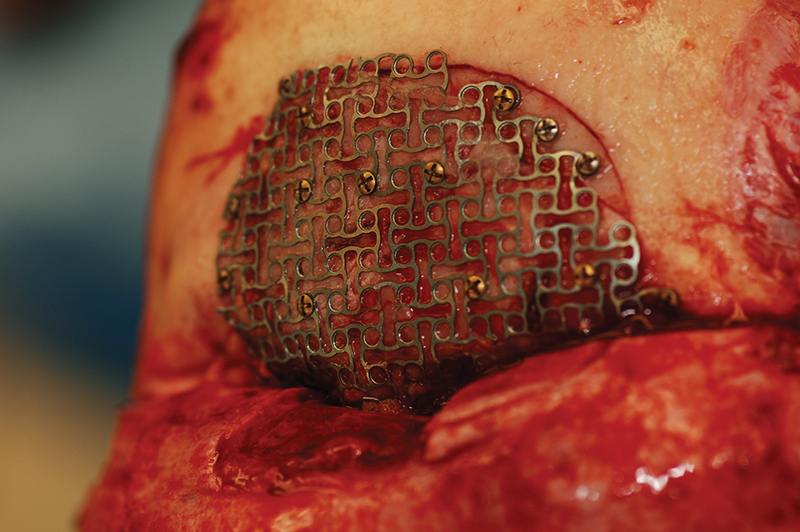

The coronal flap offers the widest exposure and may be advantageous in large and comminuted fractures of the anterior table ( Fig. 3 ). Removed fragments may be mapped using a sterile white paper or glove cover to ensure they are fixated in their original position. 20 Mucosa should be stripped as necessary, to prevent entrapment and subsequent mucocele formation. While still the gold standard, this wide approach carries the associated morbidity of scarring, alopecia, headaches, and paresthesia. Consequently, there has been a development of less invasive open approaches. Lee et al. described a subbrow approach with endoscopic assistance. Once exposed, the periosteum is removed from the fragments for fixation with absorbable plates. 21 This area may also be approached endoscopically via scalp incisions, similar to a brow lift with subperiosteal dissection. 22 Once the fracture is exposed, a porous polyethylene implant is trimmed to size and secured with screws transcutaneously. 23

Fig. 3.

A coronal flap offers wide exposure of the frontal sinus. In this case, a mesh aids in reapproximating a significantly comminuted anterior table fracture.

If left intact, the periosteum and mucosa surrounding fractured anterior segments offers expanded techniques as they might provide adequate temporary fixation. Spinelli et al. performed closed reduction with a percutaneous screw in 15 patients. However, the authors felt this technique would not be adequate for complex fractures, as they converted to open techniques in three patients due to unstable reduction. In a similar fashion, percutaneous screw placement can also be performed with endoscopic assistance. By dissecting endoscopically in the subgaleal plane, the periosteum is preserved and both screw placement along with reduction of the fractured fragment can be visualized. 24

Anterior table fractures may also be reduced from within the frontal sinus with endoscopic assistance particularly if comminution is minimal. The dome shape of the anterior wall sometimes allows for a depressed fracture to be stably “popped up” similar to a closed nasal reduction. Visualization of the frontal sinus at the time of repair also allows for assessment of the posterior wall and FSOT. The frontal sinus may be accessed via a marginal eyebrow incision and trephination, allowing for reduction of the fragments with a periosteal elevator. 25 Once elevated, an external splint is an option to maintain the contour to of the anterior table ( Fig. 4 ). Recently, endoscopic techniques have been successful without the need for external incisions. After obtaining adequate exposure with a Draf IIb or III ( Table 1 ), the anterior segment can be manually reduced with angled instruments and supported with packing and temporary stents. 26

Fig. 4.

The anterior table may be reduced via medial sub-brow trephine incisions. An external splint maintains the dome-shaped contour of the anterior table.

Table 1. Classifications of frontal sinusotomies according to Draf.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Draf I | Anterior ethmoidectomy, without instrumentation of the frontal sinus |

| Draf IIa | Standard frontal sinusotomy, clearance of tissue from the lamina papyracea to the middle turbinate |

| Draf IIb | Opening of lamina papyracea to septum |

| Draf III (Modified Lothrop) | Removal of frontal intersinus septum, frontal beak, and superior septum, from lamina papyracea to contralateral lamina |

Depending on patient preferences and the degree of anterior table displacement, delayed intervention may be appropriate. A variety of soft tissue fillers including collagen, hyaluronic acid, poly-L-lactic acid, and fat injectables are an option to restore forehead contouring. 27 28

The choice of approach of incision to depends on not only the severity of the anterior table fracture, but also patient and surgeon preference. In general, mildly displaced fractures of large segments of the anterior table are best approached with less invasive techniques such as percutaneous screw reduction, trephination, or purely endoscopic approaches. However, with larger, more comminuted fractures, the coronal incision offers the best exposure and remains the gold standard. Yet, with multiple studies reporting the safety of observing anterior table fractures, along with favorable cosmetic outcomes after swelling has subsided, there is a trend toward managing these fractures conservatively. 29

Posterior Fractures

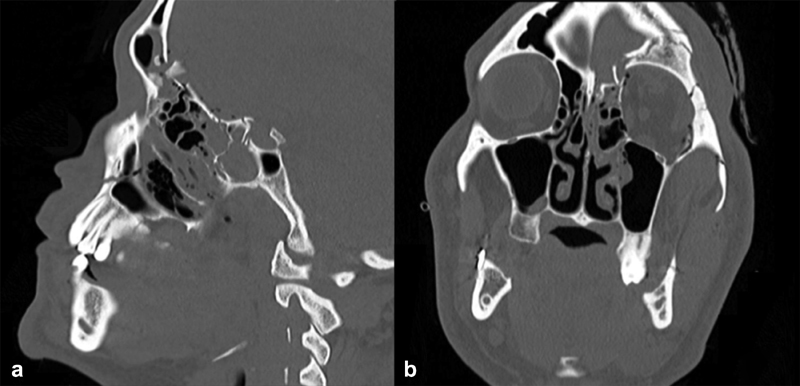

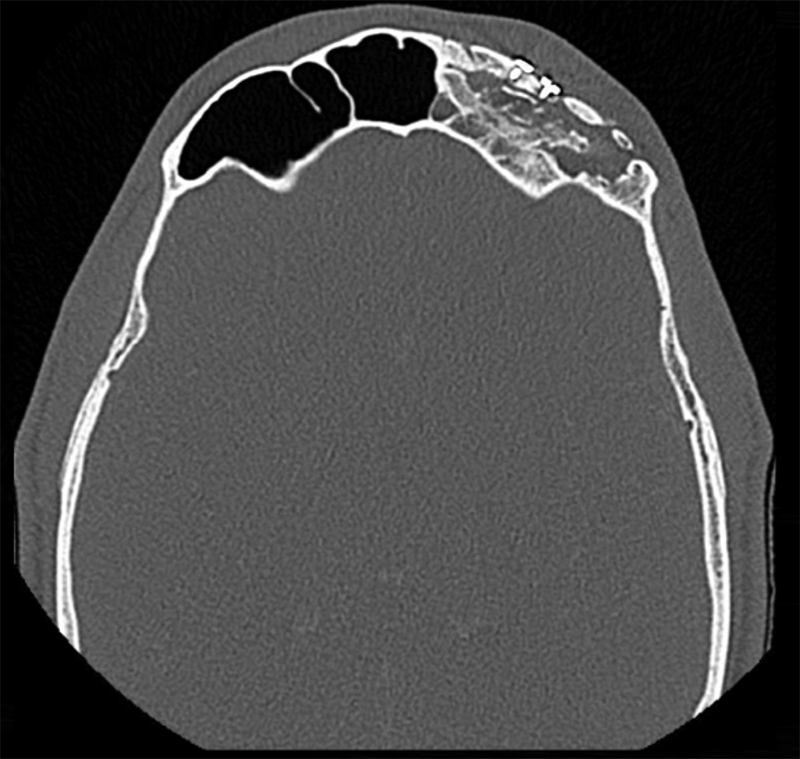

Fractures isolated to the posterior table are rarely observed (1–7%) 16 30 31 and are more common in younger patients. Typically, the posterior table is fractured in conjunction with injuries to the anterior table and FSOT ( Fig. 5 ). The sinus septae may transmit some of the anterior force to the posterior wall, or there may be direct posterior wall disruption.

Fig. 5.

(a) CT in the sagittal plane demonstrating a displaced, comminuted fracture of the posterior table. There are also associated fractures of the anterior skull base along with obstruction of the FSOT with bony fragments. (b) CT in the coronal plane of the same fracture.

Repair or removal of the posterior table is performed most commonly to prevent intracranial complications, including CSF leaks, meningitis, encephalitis, and brain abscess. Mucocele formation in posterior fractures is rare. In an animal study, Maturo et al examined goats six months after intentional comminuted fracture of the posterior table fracture. Gross and histologic examination suggested healing without mucosal ingrowth through the posterior table.

The indications for repair these fractures have focused mainly on the presence of persistent CSF rhinorrhea and the degree of fracture displacement or comminution on imaging. It is important to realize that the leak can come into the nose through the, fovea ethmoidalis or the cribriform plate rather than the posterior table as injury to these other areas is commonly associated with posterior table fractures. Most leaks present within 48 hours, but occasionally may be delayed and present weeks after the incident. 32

The management of CSF leaks in posterior table trauma, in addition to skull base trauma as a whole, is controversial. 33 Historically, skull base CSF leaks were managed aggressively due to high rates of lethal meningitis. 34 35 36 Yet, head of bed elevation, sinus precautions, laxatives, anti-emetics, and antitussives have resulted in resolution in 85% of 34 patients with traumatic skull base leaks within one week. 37 However, this rate of success was noted to be significantly lower in fractures of the anterior skull base. In a review of patients 53 patients with traumatic CSF rhinorrhea, (26%) resolved conservatively. 38 There is evidence for conservative management with CSF leaks associated with the posterior table. In a review of 59 posterior table fractures, 11 (19%) of which had leaks, Choi et al. similarly found that of 11 leaks, 6 (54%) resolved on their own, while the other 5 underwent repair without cranialization. 39 Similarly, Chen et al. reviewed 26 patients with posterior involving fractures and CSF leaks, of which 9 (35%) resolved with conservative management. 18 These studies are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2. Summary of conservative management of traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leaks.

| Author | Year | Number of Patients | Fracture Location | Non-operative Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell et al. | 2004 | 34 | Skull base(9 rhinorrhea, 25 otorrhea) | Nasal Precautions, laxitives, anti-emetics, antitussives, Lumbar drain | 85% (29/34) resolved at one week |

| Yilmazlar et al. | 2005 | 53 | Anterior skull base | Head of bed elevation, nasal precautions | 26.4 (14/53) resolved at one week |

| Chen et al. | 2006 | 26 | Posterior table of frontal sinus | Not specified | 9/26 (35%) resolved |

| Choi et al. | 2012 | 11 | Posterior table of frontal sinus | Lumbar drain, head of bed elevation, ventriculostomy | 6/11 (54%) resolved |

From these small cohorts of patients, it is clear that posterior table CSF leaks are a rare event covered by few publications in the literature. Prospective, randomized trials would also be difficult, both ethically and from a power standpoint.

The degree of displacement of the posterior table on imaging has been used as an indication for repair, mostly as it relates to the presence of a CSF leak. Classically, Rohrich and Hollier described a displacement greater than the width of the posterior table as an indication for cranialization. 40 This protocol is still utilized today. 41 Dalla Torre et al. found a high incidence of CSF leak with displacement of 5mm or more and therefore recommended operative intervention for these fractures. 42

Despite antibiotic prophylaxis and conservative management, the risk of infection with prolonged traumatic CSF leaks is high. 43 44 The timing of repair depends on multiple patient factors, but most recommend repair after an observation period of 2–7 days of conservative management including antibiotics along with lumbar drainage and other measures to reduce intracranial pressure. 18 39 In a review of 242 surgically managed frontal sinus fractures, 5.8% had serious infections including meningitis, osteomyelitis, brain abscess, and frontal sinus abscess. 30 Patients who were delayed over 48 hours from surgery had a statistically significant 4.03 fold higher risk of these serious complications. 30 Interestingly, lumbar drainage and antibiotic use beyond 48 hours post operatively did not affect this infectious risk. 30 Taken together, an observation period of CSF leaks in posterior table fractures of up to seven days is probably reasonable( Table 3 ). However, overall surgeon judgment and significant displacement of the posterior segment over 5mm may expedite the timing of repair.

Table 3. Complications of frontal sinus posterior table and skull base fractures.

| Author | Year | n | Intervention | Fracture /Leak Location | Prophylactic Antibiotics | Pre-op CSF Leak | Follow up length, average | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhavana et al. | 2014 | 5 | 100% Frontal trephine, endoscopic assistance | Frontal sinus posterior table | Not mentioned | 100% | 12 Months | None |

| Dalla Tore et al. | 2014 | 164 | 33% ORIF 5.5% Obliteration 55.5% Observation |

Frontal sinus posterior table | Not mentioned | 15.9% | 12 Months 24 Months |

15.2% Headache/pain Asymmetry Scar |

| Bellamy et al. | 2013 | 242 | 40% Cranialization 23.3% Obliteration 36.7% ORIF |

Frontal sinus posterior table | Yes, evaluated antibiotic use >48 hours | 36.1% | 7.4 Months | 5.8% infectious complications(meningitis, brain abscess, osteomyelitis) 2.5% meningitis |

| Choi et al. | 2012 | 59 | 2% Cranialization 8% Obliteration 12% ORIF 78% Observation |

Frontal sinus posterior table | Not mentioned | 19% | 12 Months | 1.7% Intracranial infection |

| Pollock et al. | 2013 | 154 | 35% Cranialization 38% Observation |

Frontal sinus posterior table | Yes, 5–7d ampicillin, occasionally gentamycin | 16% | 1–20 Years | 2 Ethmoid sinusitis |

| Chen et al. | 2006 | 78 | 18% Cranialization 23% Partial obliteration 51% ORIF 8% Observation |

Frontal sinus posterior table | Not mentioned | 37.2% | 19 Months | 8% CSF leak 5% Wound infection 1.3% Meningitis |

| Strong et al. | 2006 | 130 | 21% Cranialization 71% Osteoplastic flap 6% ORIF |

Frontal sinus posterior table | Not mentioned | 11% | 6 Months | 4 (5.6%) Meningitis 2 Severe pain |

| Sakas et al. | 1998 | 48 | 42% Observation 58% Operative |

Anterior skull base | No, only in 15 after infection developed | 43.8% | 4.5 Years | 31.3% Meningitis 17.7% Meningitis in lateral frontal fractures |

| Wallis et al. | 1988 | 72 | 41% Cranialization 33% Osteoplastic flap 20% ORIF |

Anterior skull base | Not mentioned | 31% | 22 Months | 4 (6%) Meningitis |

Abbreviation: ORIF, Open reduction and internal fixation.

There are multiple ways to approach the posterior table, which include a coronal approach, trephination with endoscopic repair, and purely endoscopic techniques. Classically, these fractures were addressed via cranialization. 45 By removing all sinonasal mucosa along with the posterior table and bony overhangs, the dura and frontal lobes fill the dead space over the next weeks to months. With significantly comminuted fractures, large dural lacerations or defects are also usually present, which can be repaired with primary closure, dural grafts and/or a pericranial flap harvested at the time of fracture repair. In the modern era, the indications for cranialization are controversial, yet with significant intracranial injury necessitating a craniotomy, cranialization remains the gold standard.

Cranialization necessitates the use of a coronal flap. In addition to the complications associated with a coronal flap, cranialization carries the added early complications of sinusitis, meningitis, persistent CSF leak, and late complications including mucocele formation, CSF leaks, and osteomyelitis ( Fig. 6 ). 17 39 The incidence of meningitis after cranialization appears to have decreased over time, with ∼50% in early literature, and presently near just 2% ( Table 3 ). 3 16 Yet, less aggressive techniques have been explored to avoid the morbidity of the coronal flap while maintaining a lower rate of infectious complications. One less aggressive technique by Bhavana et al. describes the use of a frontal trephine with endoscopic repair in five patients with fat, bone graft, and fibrin glue in select defects 0.5 cm or less. 46

Fig. 6.

CT in the coronal plane demonstrating a right frontal sinus mucocele. The right frontal sinus is completely opacified with associated bony resorption at the superior orbit.

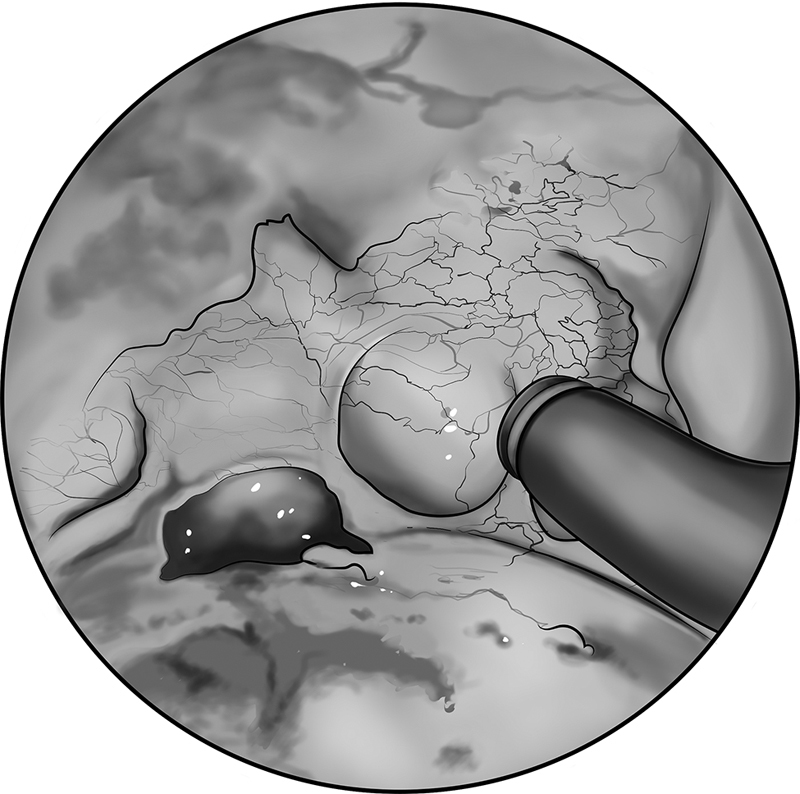

With the emerging evidence of conservative management, as well as the advent of transnasal endoscopic surgery, purely endoscopic approaches have evolved as a minimally invasive option for repair of posterior table fractures ( Fig. 7 ). The first case series of transnasal management for frontal sinus CSF leaks was reported in 2006. 47 Multiple patient series have since been published demonstrating success in repairing posterior fractures. 26 48 49 Chaaban et al. describes using a Draf IIA, IIB, or III to gain initial exposure of posterior fracture, with subsequent removal of mucosa surrounding the fracture. Next, manual reduction was performed with placement of an overlay graft, and secured with glue. 48 Epidural underlay grafts were reserved for defects greater than 5mm or those with comminution. 48 Of thirteen patients treated, the only complication reported was a repeat endoscopic frontal sinusotomy for sinusitis 14 months later.

Fig. 7.

Intraoperative, endoscopic view of a posterior table frontal sinus fracture with CSF leak. After adequate exposure, the fracture is manually reduced and surrounding mucosa is removed prior to graft placement.

Simple displaced midline posterior table fractures may be best approached with endoscopic techniques, and if located on the far lateral surface, trephination allows for improved visualization and instrumentation. For significantly comminuted fractures, or injuries that otherwise necessitates an open approach, a coronal incision offers excellent exposure.

Frontal Sinus Outflow Tract Injuries

Historically, an injury to the frontal sinus outflow tract was a primary consideration for intervention in frontal sinus trauma. As with evaluating the anterior and posterior table, CT is the imaging modality of choice in diagnosing injuries to the FSOT. Indications of FSOT injury include gross obstruction, fracture of the frontal sinus floor, and fracture of the anterior table medial wall ( Fig. 5 ). 17 While only involvement of one of these structures constitutes an FSOT injury, with multiply affected areas, complications increase. 17

Intervention in injuries to the FSOT aims to prevent the infectious complications due to obstruction, including sinusitis, osteomyelitis, and mucocele formation. Similarly to posterior table fractures, FSOT injuries were historically managed aggressively with exploration followed by cranialization or obliteration. 1 3 50 However, there has been increasing evidence for conservative management. 51 52 In a prospective study of eight patients with frontal recess injury, a CT scan performed at least 6 weeks after injury showed spontaneous ventilation in seven (87.5%). 53 Smith et al. had similar results in five of seven (71.4%) patients treated conservatively. 52 Patel et al. followed four patients with FSOT involving injuries, with one requiring operative intervention for continued opacification. 29

Cranialization versus obliteration in FSOT injuries has long been debated. 17 54 55 56 57 Rodriguez et al., in a 26-year review of 857 patients with frontal sinus fractures, found that the complication rate with autologous fat obliteration was higher at 22% in comparison to cranialization at 8.4% in patients with FSOT injury. 17 However further studies have demonstrated significantly lower complication rates with obliteration. 16 18 58 59

In the setting of trauma, the FSOT is usually approached through existing lacerations or fractures of the anterior table of the frontal sinus. Classically, an osteoplastic flap may be created by outlining the frontal sinus from a 6-foot Caldwell X-ray template, or alternatively a wire probe can be used to palpate the sinus borders through a trephine placed at the nasion. 60 These techniques are may not be suitable in the setting of trauma, however.. Obliteration is also possible through a brow incision and subsequent trephination for endoscopic visualization. 61 Once widely exposed, the frontal sinus mucosa along with any bony septations or irregularities are meticulously removed. Many authors recommend drilling to bleeding bone to ensure mucosal eradication as well as providing a vascularized bed for graft implantation. 22 55 62 63

There are numerous options available for graft material to plug the FSOT. The ideal grafting material is one that is minimally reactive, handles easily, and has a high rate of take with minimal donor site morbidity. Autologous bone is readily available and offers reliable surveillance on CT imaging. Other less dense materials, such as fat, could be mistaken for mucoceles on follow up imaging ( Fig. 8 ). Outcomes using bone grafts have been mixed. One study found comparable complications, 10%, in sixty patients who had their frontal sinuses obliterated with either calvarial bone dust or demineralized bone matrix. 58

Fig. 8.

CT in the coronal plane of a 33-year-old male who underwent left frontal sinus obliteration with abdominal fat and temporalis fascia ten years prior due to trauma. There is osteoneogenesis with soft tissue densities representing fat. While no mucocele is identified, this patient underwent re-exploration due to persistent left sided frontal pain.

Alloplastic materials have no associated donor site morbidity but have added cost with a theoretical higher rate of infection and extrusion. Alloplastic options include hydroxyapatite cement, lyophilized cartilage, methyl methacrylate, and bioactive glass. 59 64 65 66 Hydroxyapatite cement is probably the most commonly used alloplastic material with a wide variety of applications in craniofacial reconstruction. 67 It has also demonstrated complete osseointegration with minimal complications in eleven patients after frontal sinus obliteration. 68 Furthermore, the cement may be contoured to create a new anterior table in cases of severe comminution, an advantage over other grafting materials. Ideally one can avoid obliteration all together due to the possibility of late complications, and if necessary, autologous bone is generally recommended over other autologous or alloplastic materials.

Failed obliteration is becoming increasingly recognized. It is imperative to be familiar with the historical aspects of obliteration as well as the variety of materials used, as patients may present years after their initial surgery. Imaging, especially CT, is the first step in evaluating the graft material as well evidence of mucocele formation or osteomyelitis. Yet graft density and water content may change over time, and imaging may not clearly demonstrate these changes. Therefore, it is recommended that any patient with persistent symptoms after obliteration warrants operative exploration. 56 Failed obliterations may be reversed with open or endoscopic techniques, and rarely repeat obliteration is necessary. 56

Transnasal endoscopic techniques have evolved to manage most FSOT pathology. Naturally, this has extended into FSOT trauma as well. Endoscopic techniques allow for preservation of the frontal sinus as well as superior post-treatment surveillance. Since FSOT injuries often involve anterior and posterior table fractures, clearance of the FSOT via Draf IIb or Draf III preserves functional sinus drainage. Woodworth et al. has reported excellent outcomes in forty-six patients managed endoscopically between 2008 and 2016. Interestingly, the indications for repair in these patients included only cosmetic defects to the anterior table and CSF leak associated with posterior table fractures and not necessarily injury to the FSOT. The frontal sinusotomy used to address these fractures effectively clears an obstructed FSOT.

Given the increasing evidence for spontaneous ventilation even after significant FSOT injuries, observation with expectant management is often appropriate. 29 52 53 Patel et al. proposed a protocol that all patients with FSOT involving injuries undergo a CT in three months, and only those with complete opacification be considered for endoscopic versus open repair. 29 Yet long-term outcomes in these patients with spontaneous ventilation on imaging are still unknown. Patients should be made aware that any new swelling or pain warrants immediate re-evaluation as the risk of mucocele formation may still happen years in the future. In repairing these defects, in addition to a wide frontal sinusotomy, supportive packing and temporary stenting is recommended. 26

FSOT involving injuries are managed across multiple surgical specialties with backgrounds in oral and maxillofacial surgery, otolaryngology, and plastic surgery, each with unique training backgrounds. In a 2016 cross-sectional survey across these specialties, plastic and oral and maxillofacial surgeons were more likely to perform obliteration of anterior fractures requiring repair with a concomitant injury to the FSOT. 69 Those with a background in otolaryngology, on the other hand, favored ORIF. 69 Yet all specialties favored observation or FESS for FSOT injuries. 69 These changing management strategies appear to impact all specialties, demonstrating the familiarity required in both endoscopic and open techniques.

Conclusions

The treatment of frontal sinus fractures has changed dramatically over the past half-century. Through this time various algorithms have been proposed. 4 17 18 26 29 41 42 45 52 55 70 Historically, these fractures were managed aggressively with open techniques resulting in obliteration or cranialization. These approaches are still indispensable in select cases. Yet successive case series have demonstrated favorable outcomes with conservative management. Concurrently, there has been an increasing role of minimally invasive endoscopic techniques, both for primary and expectant management. Taken together, there has been a movement toward sinus preservation. For anterior and posterior table fractures, there has been a shift away from operating based on imaging findings alone. Rather, the patient must be evaluated clinically for forehead contour deformity and persistent CSF leak. If present, there are a variety of both open and endoscopic approaches available to the surgeon. The FSOT may also be addressed simultaneously if there is involvement. Otherwise, in patients with injuries to the FSOT, appropriate counseling and close follow up with repeat CT imaging after 6 weeks to confirm sinus ventilation is appropriate.

Acknowledgments

April Crane, medical illustrations, Figs. 1(b) and 7 .

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Gerbino G, Roccia F, Benech A, Caldarelli C.Analysis of 158 frontal sinus fractures: current surgical management and complications J Craniomaxillofac Surg 20002803133–139.. Doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luce E A.Frontal sinus fractures: guidelines to management Plast Reconstr Surg 19878004500–510.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3659160Accessed May 29, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallis A, Donald P J.Frontal sinus fractures: a review of 72 cases Laryngoscope 198898(6 Pt 1):593–598.. Doi: 10.1288/00005537-198806000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell R B, Dierks E J, Brar P, Potter J K, Potter B E.A protocol for the management of frontal sinus fractures emphasizing sinus preservation J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20076505825–839.. Doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai S S, Mossop C, Diaconu S Cet al. The “Crumple Zone” hypothesis: Association of frontal sinus volume and cerebral injury after craniofacial trauma J Craniomaxillofac Surg 201745071094–1098.. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee T S, Kellman R, Darling A.Crumple zone effect of nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses on posterior cranial fossa Laryngoscope 2014124102241–2246.. Doi: 10.1002/lary.24644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J L, Branstetter B F, IV, Snyderman C H.Frontal sinus volume predicts incidence of brain contusion in patients with head trauma J Trauma Acute Care Surg 20147602488–492.. Doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aaa4bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahum A M.The biomechanics of maxillofacial trauma Clin Plast Surg 197520159–64.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1116327Accessed September 16, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah R K, Dhingra J K, Carter B L, Rebeiz E E.Paranasal sinus development: a radiographic study Laryngoscope 200311302205–209.. Doi: 10.1097/00005537-200302000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Bar M, Lieberman S, Casiano R. Surgical Anatomy and Embryology of the Frontal Sinus. Front Sinus2016:16–31.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-48523-1_2 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danesh-Sani S A, Bavandi R, Esmaili M.Frontal sinus agenesis using computed tomography J Craniofac Surg 20112206e48–e51.. Doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318231e26c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Çakur B, Sumbullu M A, Durna N B.Aplasia and agenesis of the frontal sinus in Turkish individuals: a retrospective study using dental volumetric tomography Int J Med Sci 2011803278–282.. Doi: 10.7150/ijms.8.278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wormald P J, Hoseman W, Callejas Cet al. The International Frontal Sinus Anatomy Classification (IFAC) and Classification of the Extent of Endoscopic Frontal Sinus Surgery (EFSS) Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2016607677–696.. Doi: 10.1002/alr.21738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amine M A, Anand V.Anatomy and Complications: Safe Sinus Otolaryngol Clin North Am 20154805739–748.. Doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renzi G, Carboni A, Gasparini G, Perugini M, Becelli R.Taste and olfactory disturbances after upper and middle third facial fractures: a preliminary study Ann Plast Surg 20024804355–358.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12068215Accessed June 24, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strong E B, Pahlavan N, Saito D.Frontal sinus fractures: a 28-year retrospective review Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 200613505774–779.. Doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez E D, Stanwix M G, Nam A Jet al. Twenty-six-year experience treating frontal sinus fractures: a novel algorithm based on anatomical fracture pattern and failure of conventional techniques Plast Reconstr Surg 2008122061850–1866.. Doi: 10.1097/prs.0b013e31818d58ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen K T, Chen C T, Mardini S, Tsay P K, Chen Y R.Frontal sinus fractures: a treatment algorithm and assessment of outcomes based on 78 clinical cases Plast Reconstr Surg 200611802457–468.. Doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000227738.42077.2d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacIsaac Z M, Naran S, Losee J E.Pediatric frontal sinus fracture conservative care: complete remodeling with growth and development J Craniofac Surg 201324051838–1840.. Doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31828f2c8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rai A, Shrivastava A, Khan M M.“Bone Mapping/Sketching” in Management of Anterior Table Frontal Sinus Fracture J Maxillofac Oral Surg 20171601127–130.. Doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0917-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee Y, Choi H G, Shin D Het al. Subbrow approach as a minimally invasive reduction technique in the management of frontal sinus fractures Arch Plast Surg 20144106679–685.. Doi: 10.5999/aps.2014.41.6.679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strong E B.Frontal sinus fractures: current concepts Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2009203161–175.. Doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1234020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim K K, Mueller R, Huang F, Strong E B.Endoscopic repair of anterior table: frontal sinus fractures with a Medpor implant Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 200713604568–572.. Doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egemen O, Özkaya Ö, Aksan T, Bingöl D, Akan M.Endoscopic repair of isolated anterior table frontal sinus fractures without fixation J Craniofac Surg 201324041357–1360.. Doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182902518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meiklejohn B D, Lynham A, Borgna S C.A simplified approach for the reduction of specific closed anterior table frontal sinus fractures Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014520181–84.. Doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grayson J W, Jeyarajan H, Illing E A, Cho D Y, Riley K O, Woodworth B A.Changing the surgical dogma in frontal sinus trauma: transnasal endoscopic repair Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2017705441–449.. Doi: 10.1002/alr.21897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y W, Lee D H, Cheon Y W.Secondary Reconstruction of Frontal Sinus Fracture Arch Craniofac Surg 20161703103–110.. Doi: 10.7181/acfs.2016.17.3.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaney S W.Treatment strategies for frontal sinus anterior table fractures and contour deformities J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 201669081037–1045.. Doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel S A, Berens A M, Devarajan K, Whipple M E, Moe K S.Evaluation of a minimally disruptive treatment protocol for frontal sinus fractures JAMA Facial Plast Surg 20171903225–231.. Doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellamy J L, Molendijk J, Reddy S Ket al. Severe infectious complications following frontal sinus fracture: the impact of operative delay and perioperative antibiotic use Plast Reconstr Surg 201313201154–162.. Doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182910b9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox P M, Garza R, Dusch M, Hwang P H, Girod S.Management of frontal sinus fractures: treatment modality changes at a level I trauma center J Craniofac Surg 201425062038–2042.. Doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewin W. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea in closed head injuries. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13190185. Br J Surg. 1954;42(171):1–18. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004217102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman J S, Farnoosh S, Kellman R M, Tatum S A., IIISkull Base Trauma: Clinical Considerations in Evaluation and Diagnosis and Review of Management Techniques and Surgical Approaches Semin Plast Surg 20173104177–188.. Doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eljamel M S, Foy P M.Acute traumatic CSF fistulae: the risk of intracranial infection Br J Neurosurg 1990405381–385.. Doi: 10.3109/02688699008992759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eljamel M SM, Foy P M.Post-traumatic CSF fistulae, the case for surgical repair Br J Neurosurg 1990406479–483.. Doi: 10.3109/02688699008993796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Alobid I, Mullol J, Trobat F, Tomás-Barberán M.Closure of cerebrospinal fluid leaks prevents ascending bacterial meningitis Rhinology 20054304277–281.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16405272Accessed May 29, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell R B, Dierks E J, Homer L, Potter B E.Management of cerebrospinal fluid leak associated with craniomaxillofacial trauma J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20046206676–684.. Doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yilmazlar S, Arslan E, Kocaeli Het al. Cerebrospinal fluid leakage complicating skull base fractures: analysis of 81 cases Neurosurg Rev 2006290164–71.. Doi: 10.1007/s10143-005-0396-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi M, Li Y, Shapiro S A, Havlik R J, Flores R L.A 10-year review of frontal sinus fractures: clinical outcomes of conservative management of posterior table fractures Plast Reconstr Surg 201213002399–406.. Doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182589d91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohrich R J, Hollier L H.Management of frontal sinus fractures. Changing concepts Clin Plast Surg 19921901219–232.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1537220Accessed June 1, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vu A T, Patel P A, Chen W, Wilkening M W, Gordon C B.Pediatric frontal sinus fractures: outcomes and treatment algorithm J Craniofac Surg 20152603776–781.. Doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalla Torre D, Burtscher D, Kloss-Brandstätter A, Rasse M, Kloss F.Management of frontal sinus fractures--treatment decision based on metric dislocation extent J Craniomaxillofac Surg 201442071515–1519.. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Appelbaum E.Meningitis following trauma to the head and face JAMA 1960173161818–1822.. Doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020340036010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakas D E, Beale D J, Ameen A Aet al. Compound anterior cranial base fractures: classification using computerized tomography scanning as a basis for selection of patients for dural repair J Neurosurg 19988803471–477.. Doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonty A A, Marciani R D, Adornato D C.Management of frontal sinus fractures: a review of 33 cases J Oral Maxillofac Surg 19995704372–379., discussion 380–381http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10199487Accessed May 29, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhavana K, Kumar R, Keshri A, Aggarwal S.Minimally invasive technique for repairing CSF leaks due to defects of posterior table of frontal sinus J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 20147503183–186.. Doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodworth B A, Schlosser R J, Palmer J N.Endoscopic repair of frontal sinus cerebrospinal fluid leaks J Laryngol Otol 200511909709–713.. Doi: 10.1258/0022215054797961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaaban M R, Conger B, Riley K O, Woodworth B A.Transnasal endoscopic repair of posterior table fractures Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012147061142–1147.. Doi: 10.1177/0194599812462547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones V, Virgin F, Riley K, Woodworth B A.Changing paradigms in frontal sinus cerebrospinal fluid leak repair Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2012203227–232.. Doi: 10.1002/alr.21019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson B C, Davidson B, Corey J P, Haydon R C., IIIComparison of complications following frontal sinus fractures managed with exploration with or without obliteration over 10 years Laryngoscope 19889805516–520.. Doi: 10.1288/00005537-198805000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wichova H, Chiu A G, Villwock J A.Does the frontal sinus need to be obliterated following fracture with frontal sinus outflow tract injury? Laryngoscope 2017127091967–1969.. Doi: 10.1002/lary.26601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith T L, Han J K, Loehrl T A, Rhee J S.Endoscopic management of the frontal recess in frontal sinus fractures: a shift in the paradigm? Laryngoscope 200211205784–790.. Doi: 10.1097/00005537-200205000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jafari A, Nuyen B A, Salinas C R, Smith A M, DeConde A S.Spontaneous ventilation of the frontal sinus after fractures involving the frontal recess Am J Otolaryngol 20153606837–842.. Doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pollock R A, Hill J L, Jr, Davenport D L, Snow D C, Vasconez H C.Cranialization in a cohort of 154 consecutive patients with frontal sinus fractures (1987-2007): review and update of a compelling procedure in the selected patient Ann Plast Surg 2013710154–59.. Doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182468198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie C, Mehendale N, Barrett D, Bui C J, Metzinger S E.30-year retrospective review of frontal sinus fractures: The Charity Hospital experience J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 20006017–15., discussion 16–18http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11373741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanowitz S J, Batra P S, Citardi M J.Comprehensive management of failed frontal sinus obliteration Am J Rhinol 20082203263–270.. Doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gossman D G, Archer S M, Arosarena O.Management of frontal sinus fractures: a review of 96 cases Laryngoscope 2006116081357–1362.. Doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000226009.00145.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zubillaga Rodríguez I, Lora Pablos D, Falguera Uceda M I, Díez Lobato R, Sánchez Aniceto G.Frontal sinus obliteration after trauma: analysis of bone regeneration for two selected methods Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20144307827–833.. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sailer H F, Grätz K W, Kalavrezos N D.Frontal sinus fractures: principles of treatment and long-term results after sinus obliteration with the use of lyophilized cartilage J Craniomaxillofac Surg 19982604235–242.. Doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(98)80019-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salamone F N, Seiden A M.Modern techniques in osteoplastic flap surgery of the frontal sinus Oper Tech Otolaryngol--Head Neck Surg 2004150161–66.. Doi: 10.1053/j.otot.2004.02.003 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ung F, Sindwani R, Metson R.Endoscopic frontal sinus obliteration: a new technique for the treatment of chronic frontal sinusitis Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 200513304551–555.. Doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monnazzi M, Gabrielli M, Pereira-Filho V, Hochuli-Vieira E, de Oliveira H, Gabrielli M.Frontal sinus obliteration with iliac crest bone grafts. Review of 8 cases Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2014704263–270.. Doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1382776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rice D H.Management of frontal sinus fractures Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004120146–48.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1537220Accessed June 1, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verret D J, Ducic Y, Oxford L, Smith J.Hydroxyapatite cement in craniofacial reconstruction Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 200513306897–899.. Doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peltola M, Aitasalo K, Suonpää J, Varpula M, Yli-Urpo A.Bioactive glass S53P4 in frontal sinus obliteration: a long-term clinical experience Head Neck 20062809834–841.. Doi: 10.1002/hed.20436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cavalieri-Pereira L, Assis A, Olate S, Asprino L, de Moraes M. Surgical treatment of frontal sinus fracture sequelae with methyl methacrylate prosthesis. Int J Burns Trauma. 2013;3(04):225–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mathur K K, Tatum S A, Kellman R M.Carbonated apatite and hydroxyapatite in craniofacial reconstruction Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003505379–383.. Doi: 10.1001/archfaci.5.5.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petruzzelli G J, Stankiewicz J A.Frontal sinus obliteration with hydroxyapatite cement Laryngoscope 20021120132–36.. Doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi K J, Chang B, Woodard C R, Powers D B, Marcus J R, Puscas L.Survey of current practice patterns in the management of frontal sinus fractures Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 20171002106–116.. Doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1599196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stanwix M G, Nam A J, Manson P N, Mirvis S, Rodriguez E D.Critical computed tomographic diagnostic criteria for frontal sinus fractures J Oral Maxillofac Surg 201068112714–2722.. Doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]