Overview

Pain, defined as “a sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage,”1 is one of the most common symptoms associated with cancer. Cancer pain or cancer-related pain is distinct from pain experienced by patients without malignancies. Pain occurs in approximately one quarter of patients with newly diagnosed malignancies, one third of patients undergoing treatment, and three quarters of patients with advanced disease,2–4 and is one of the symptoms patients fear most. Unrelieved pain denies patients comfort and greatly affects their activities, motivation, interactions with family and friends, and overall quality of life.

The importance of relieving pain and availability of effective therapies make it imperative that physicians and nurses caring for these patients be adept at the assessment and treatment of cancer pain.5–7 This requires familiarity with the pathogenesis of cancer pain; pain assessment techniques; common barriers to the delivery of appropriate analgesia; and pertinent pharmacologic, anesthetic, neurosurgical, and behavioral approaches to the treatment of cancer pain.

The most widely accepted algorithm for the treatment of cancer pain was developed by the WHO.8,9 It suggests that patients with pain be started on acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). If this is not sufficient, patients should be escalated to a weak opioid, such as codeine, and then to a strong opioid, such as morphine. Although this algorithm has served as an excellent teaching tool, the management of cancer pain is considerably more complex than this 3-tiered “cancer pain ladder” suggests.

This guideline is unique in several important ways. First, it contains several required components:

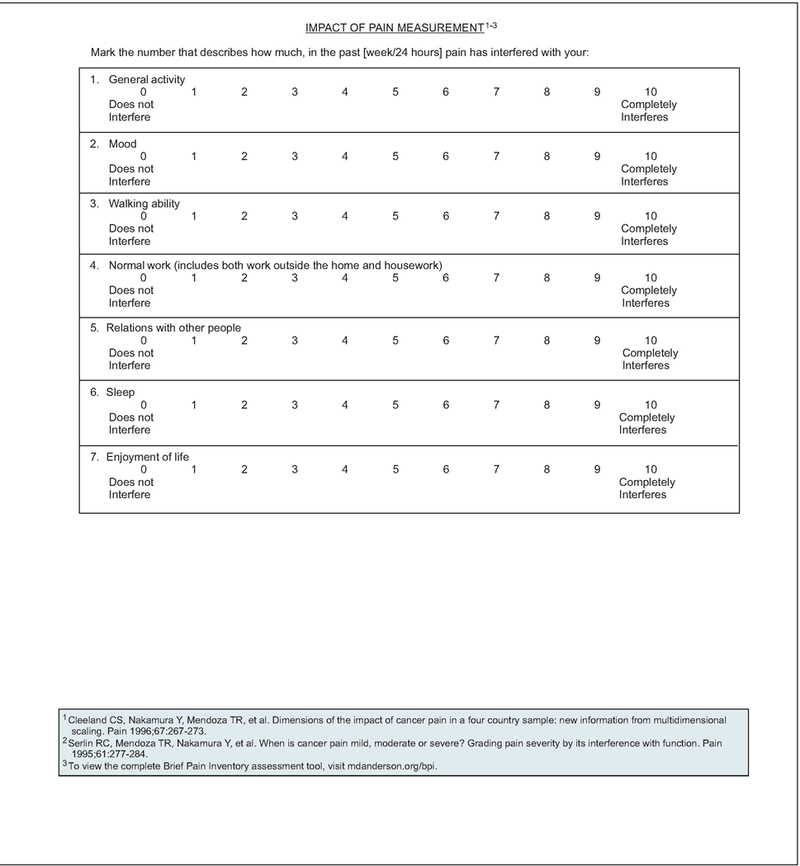

Pain intensity must be quantified by the patient (whenever possible), because the algorithm bases therapeutic decisions on a numerical value assigned to the severity of the pain.

A formal comprehensive pain assessment must be performed.

Reassessment of pain intensity must be performed at specified intervals to ensure that the therapy selected is having the desired effect.

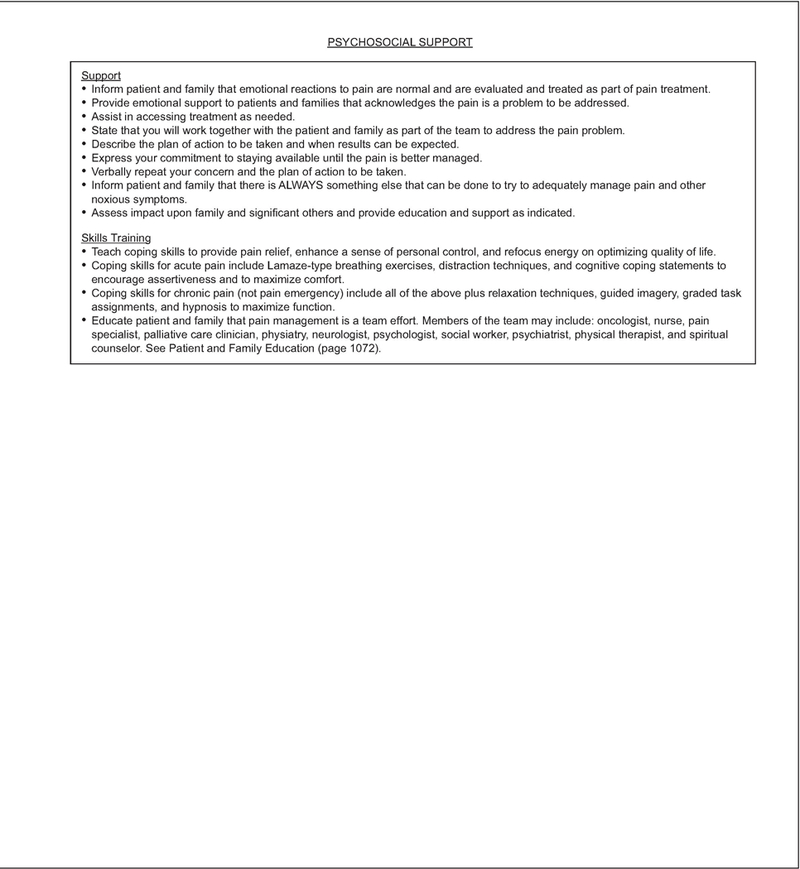

Psychosocial support must be available.

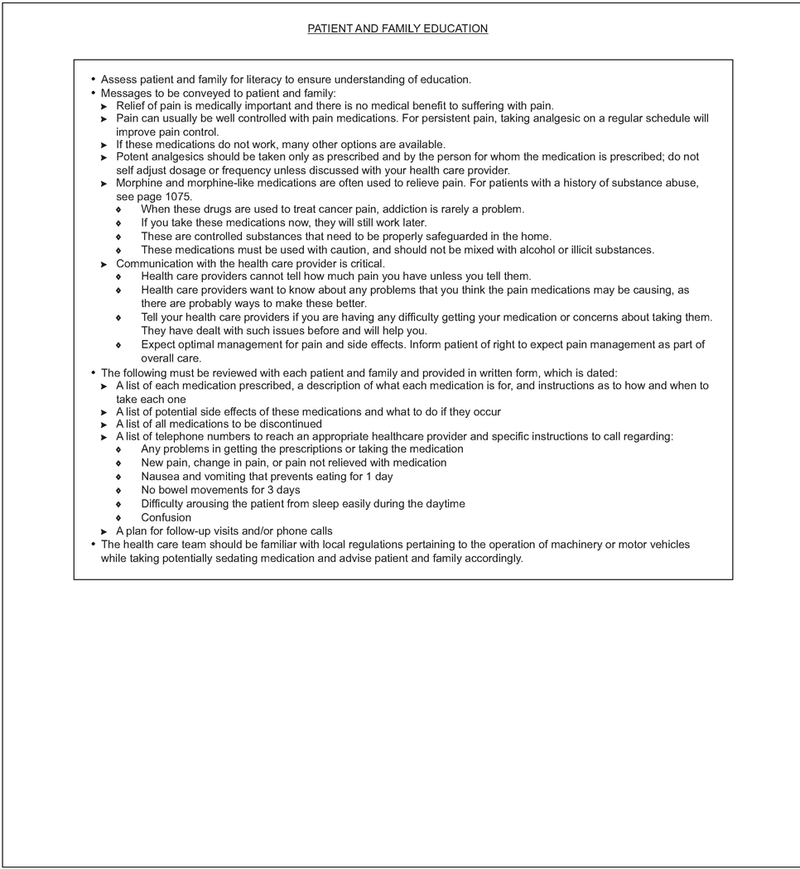

Specific educational material must be provided to the patient.

Second, the guidelines acknowledge the range of complex decisions faced in caring for these patients. As a result, they provide dosing guidelines for NSAIDs, opioids, and coanalgesics. They also provide specific suggestions for titrating and rotating opioids, escalation of opioid dosage, management of opioid adverse effects, and when and how to proceed to other techniques/interventions for the management of cancer pain.

Pathophysiologic Classification

Different types of pain occur in cancer patients. Several attempts have been made to classify pain according to different criteria. Pain classification includes differentiating between pain associated with tumor, pain associated with treatment, and pain unrelated to either. Acute and chronic pain should also be distinguished when deciding what therapy to use. Therapeutic strategy depends on the pain pathophysiology, which is determined through patient examination and evaluation. Pain has 2 predominant mechanisms of pathophysiology: nociceptive and neuropathic.10,11

Nociceptive pain is the result of injury to somatic and visceral structures and the resulting activation of nociceptors. Nociceptors are present in skin, viscera, muscles, and connective tissues. Nociceptive pain can be further divided into somatic pain and visceral pain.12 Pain described as sharp, well-localized, throbbing, and pressure-like is probably somatic nociceptive pain, and often occurs after surgical procedures or from bone metastasis. Visceral nociceptive pain is frequently described as more diffuse, aching, and cramping. It is secondary to compression, infiltration, or distension of abdominal thoracic viscera.

Neuropathic pain results from injury to the peripheral or central nervous system. This type of pain might be described as burning, sharp, or shooting. Examples of neuropathic pain include pain from spinal stenosis or diabetic neuropathy, or as an adverse effect of chemotherapy (e.g., vincristine) or radiation therapy.

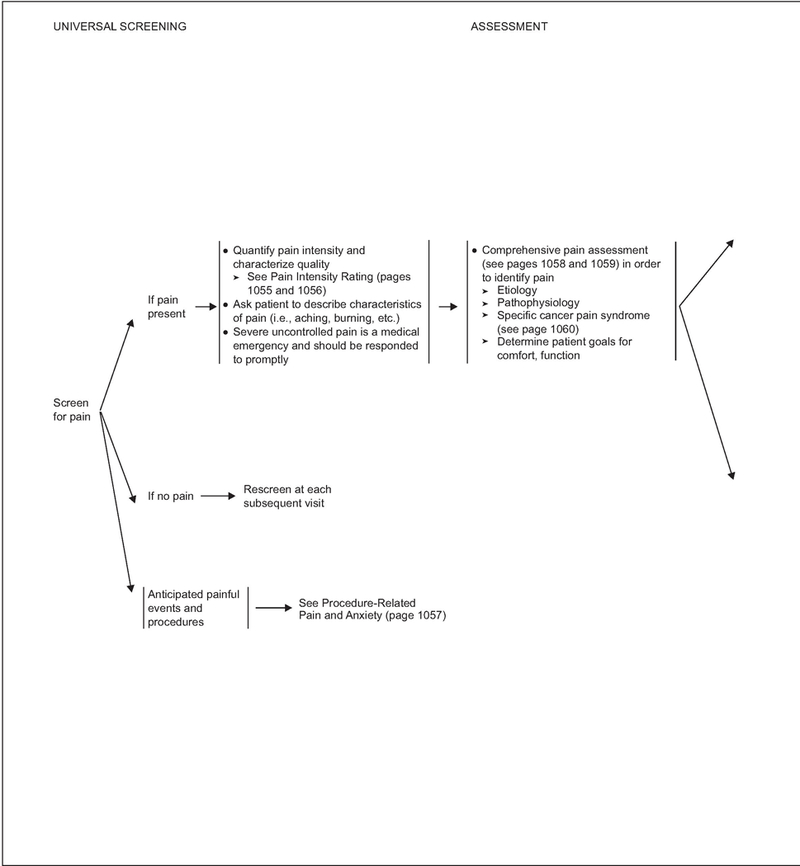

Comprehensive Pain Assessment

A comprehensive evaluation is essential to ensure proper pain management. Failure to adequately assess pain frequently leads to poor pain control. These guidelines begin with the premise that all patients with cancer should be screened for pain (page 1048) during the initial evaluation, at regular follow-up intervals, and whenever new therapy is initiated.

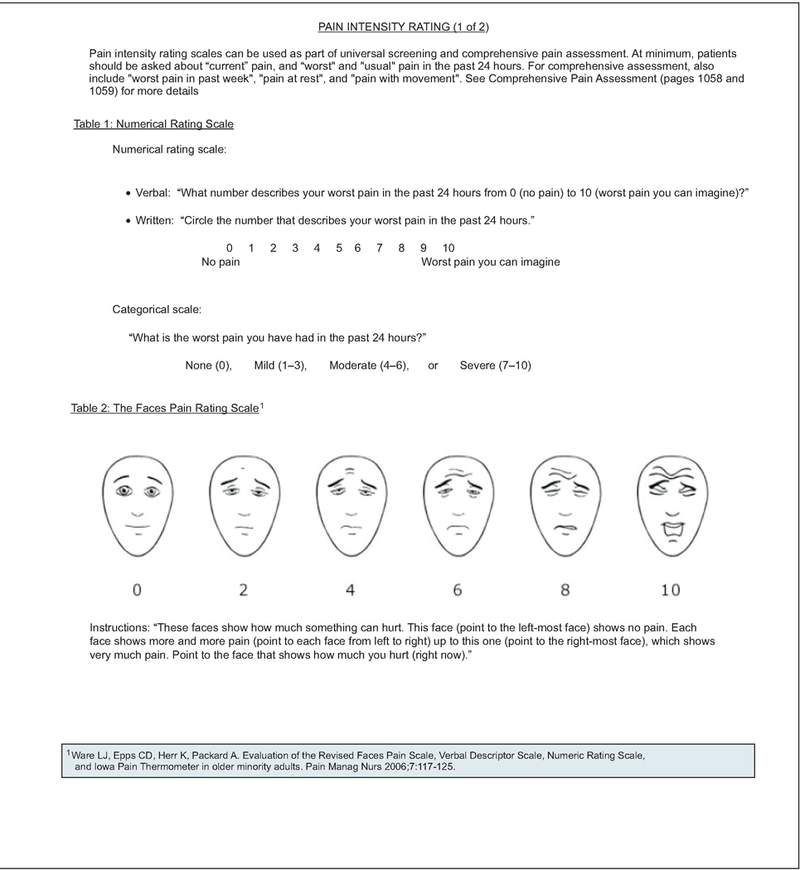

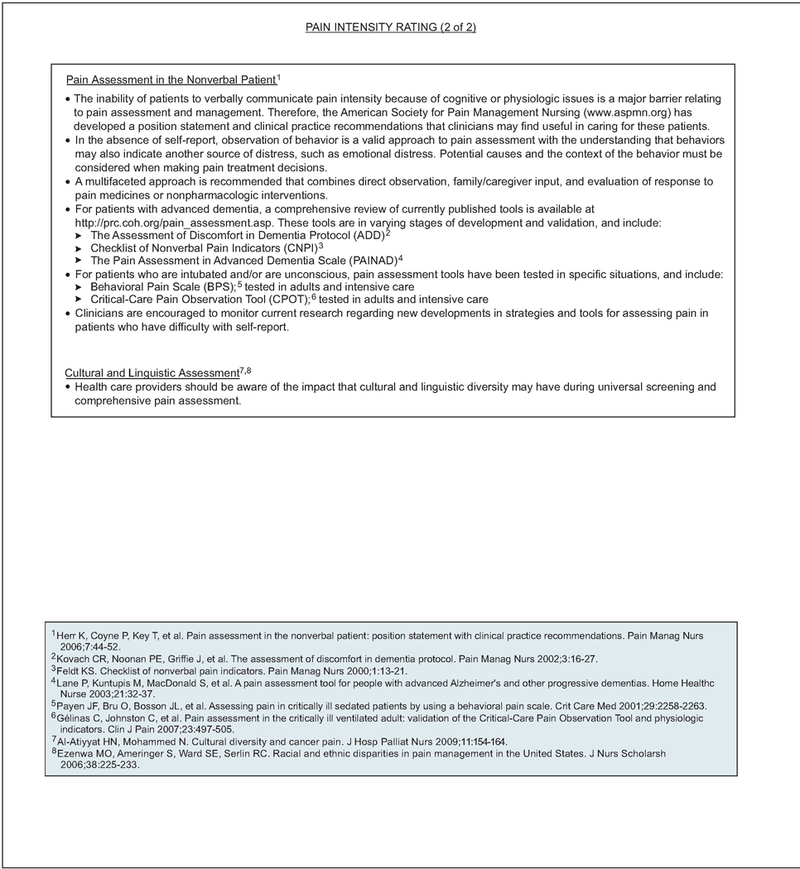

If pain is present on a screening evaluation, the pain intensity must be quantified by the patient whenever possible. Because pain is inherently subjective, patient’s self-report of pain is the current standard of care for assessment. Intensity of pain should be quantified using a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale, a categorical scale, or a pictorial scale (e.g., the Faces Pain Rating Scale; see page 1055).13–15 The Faces Pain Rating Scale may be successful for patients who have difficulty with other scales, such as children, elderly patients, and patients with language or cultural differences or other communication barriers. If the patient is unable to verbally report pain, an alternative method must be used to assess and rate the pain (see page 1056).

In addition to pain intensity, the patient should be asked to describe the characteristics of their pain (e.g., aching, burning). If the patient has no pain, rescreening should be performed at each subsequent visit or as requested. Identifying the presence of pain through repeated screening is essential to allow implementation of effective pain management.

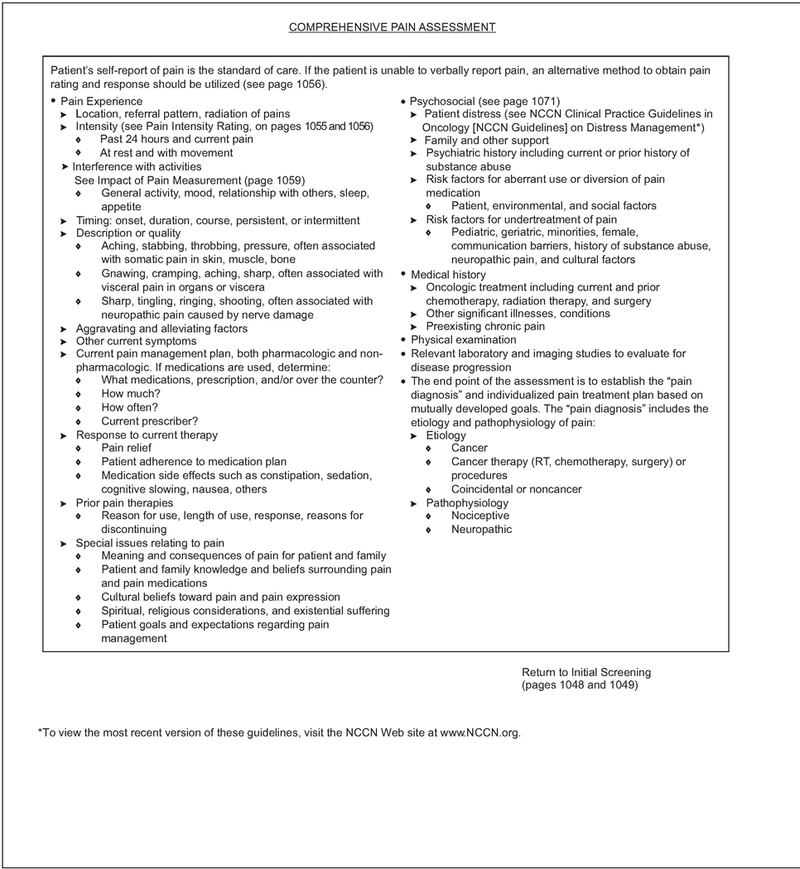

If the Pain Rating Scale score is greater than 0, a comprehensive pain assessment is initiated (see pages 1058 and 1059). The comprehensive pain assessment should focus on the type and quality of pain, pain history (e.g., onset, duration, course), pain intensity (e.g., pain experienced at rest or with movement, or that interferes with activities), location, referral pattern, radiation of pain, associated factors that exacerbate or relieve the pain, current pain management plan, patient’s response to current therapy, prior pain therapies, important psychosocial factors (e.g., patient distress, family and other support, psychiatric history, risk factors for aberrant use of pain medication, risk factors for undertreatment of pain), and other special issues relating to pain (e.g., meaning of pain for patient and family, cultural beliefs toward pain and pain expression, spiritual or religious considerations and existential suffering).16,17 Finally, the patient’s goals and expectations of pain management should be discussed, including level of comfort and function (see pages 1058 and 1059).

In addition, a thorough physical examination and review of appropriate laboratory and imaging studies are essential for a comprehensive pain assessment. This evaluation should enable caregivers to determine if the pain is related to an underlying cause that requires specific therapy. For example, providing only opioids to a patient experiencing pain from impending spinal cord compression is inappropriate. Without glucocorticoids and local radiation therapy, the pain is unlikely to be well controlled and the patient will remain at high risk for spinal cord injury.

The end point of comprehensive pain assessment is to diagnose the origin and pathophysiology (somatic, visceral, or neuropathic) of the pain. Treatment must be individualized based on clinical circumstances and patient wishes, with the goal of maximizing function and quality of life.

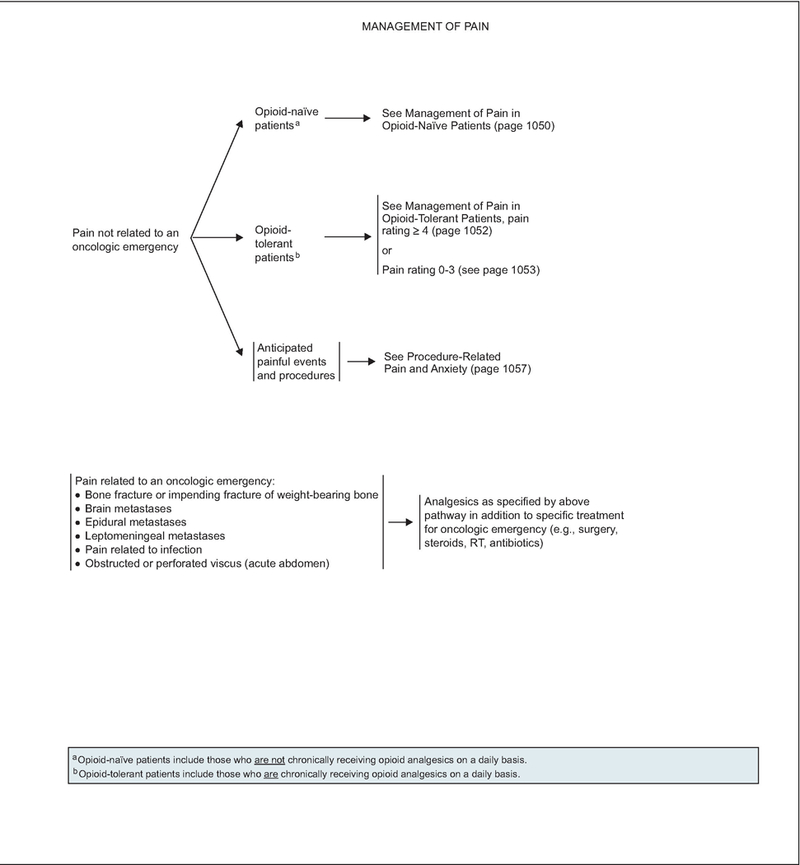

Management of Pain

For management of cancer-related pain in adults, the algorithm distinguishes 3 levels of pain intensity, based on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale (with 10 being the worst pain): severe pain (7–10); moderate pain (4–6); and mild pain (1–3).12,14

Pain related to an oncologic emergency is important to separate from pain not related to an oncologic emergency (e.g., from bone fracture or impending fracture of weight-bearing bone; brain, epidural, or leptomeningeal metastases; infection; obstructed or perforated viscus). Pain associated with oncologic emergency should be directly treated while proceeding with treatment of the underlying condition.

The algorithm also distinguishes pain that is unrelated to oncologic emergencies in patients not chronically taking opioids (opioid-naïve) from the pain experienced by those who have previously or are chronically taking opioids for cancer pain (opioid-tolerant), and also from anticipated procedure-related pain and anxiety.

According to the FDA, “patients considered opioid tolerant are those who are taking at least: 60 mg oral morphine/day, 25 mcg transdermal fentanyl/ hour, 30 mg oral oxycodone/day, 8 mg oral hydro-morphone/day, 25 mg oral oxymorphone/day, or an equianalgesic dose of another opioid for one week or longer.” Therefore, patients who do not meet these criteria for opioid-tolerant, and who have not had opioid doses at least as much as those stated for a week or more, are considered to be opioid-naïve.

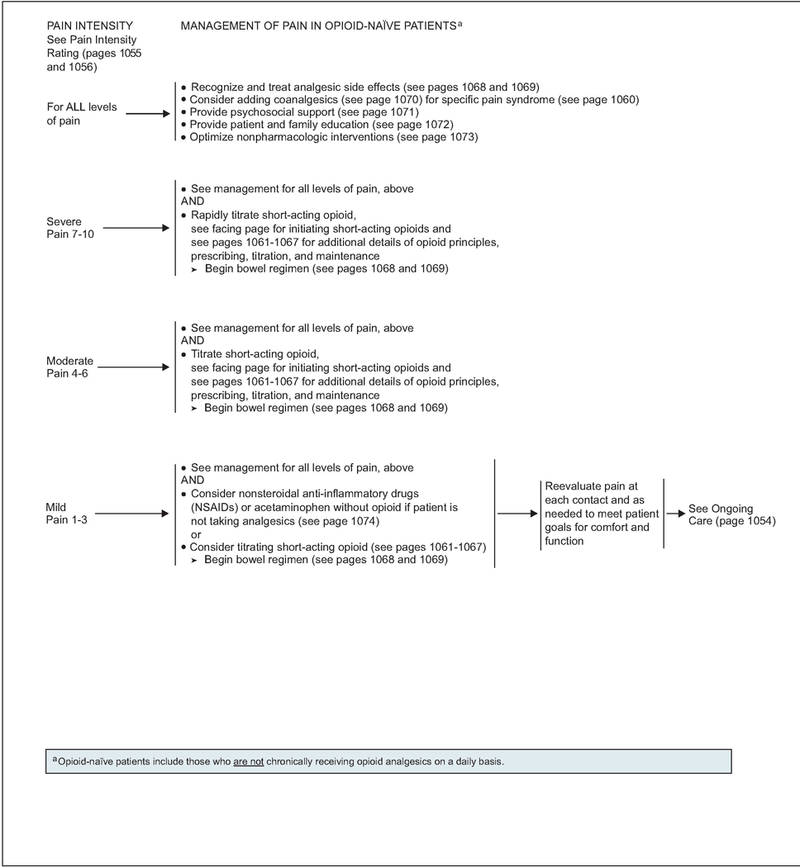

Management of Pain Not Related to an Oncologic Emergency in Opioid-Naïve Patients

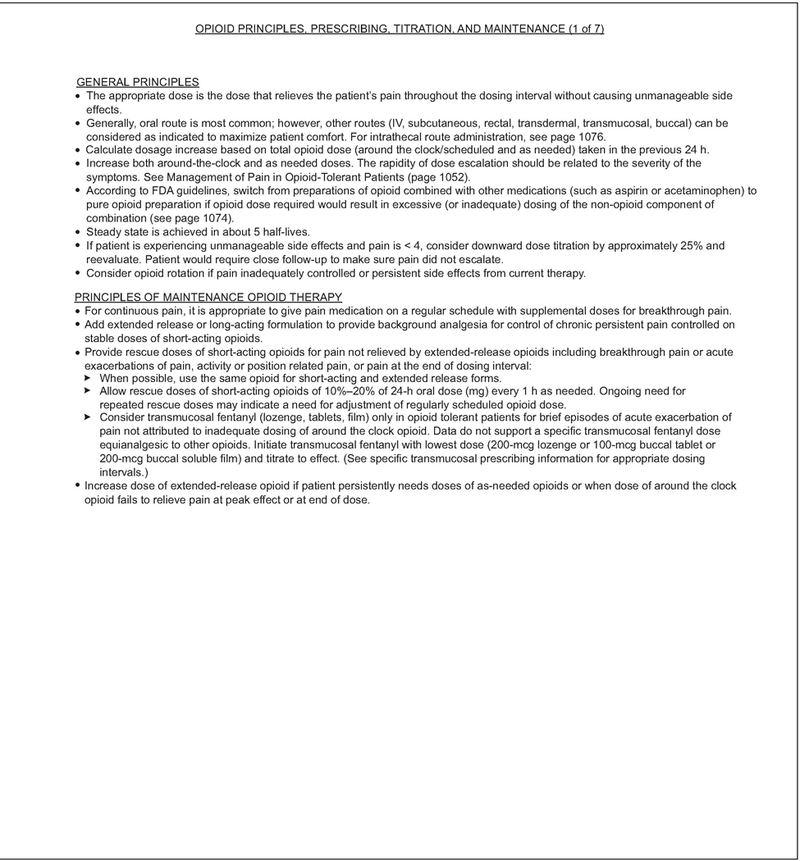

Opioid-naïve patients (those who are not chronically receiving opioids on a daily basis) experiencing severe pain (i.e., pain intensity rating 7–10) should receive rapid titration of short-acting opioids (see page 1050, and Opioid Principles, Prescribing, Titration, and Maintenance, facing page). Short-acting formulations have the advantage of rapid onset of analgesic effect. The route of opioid administration (oral vs. intravenous) is decided based on what is best suited to the patient’s ongoing analgesic needs.

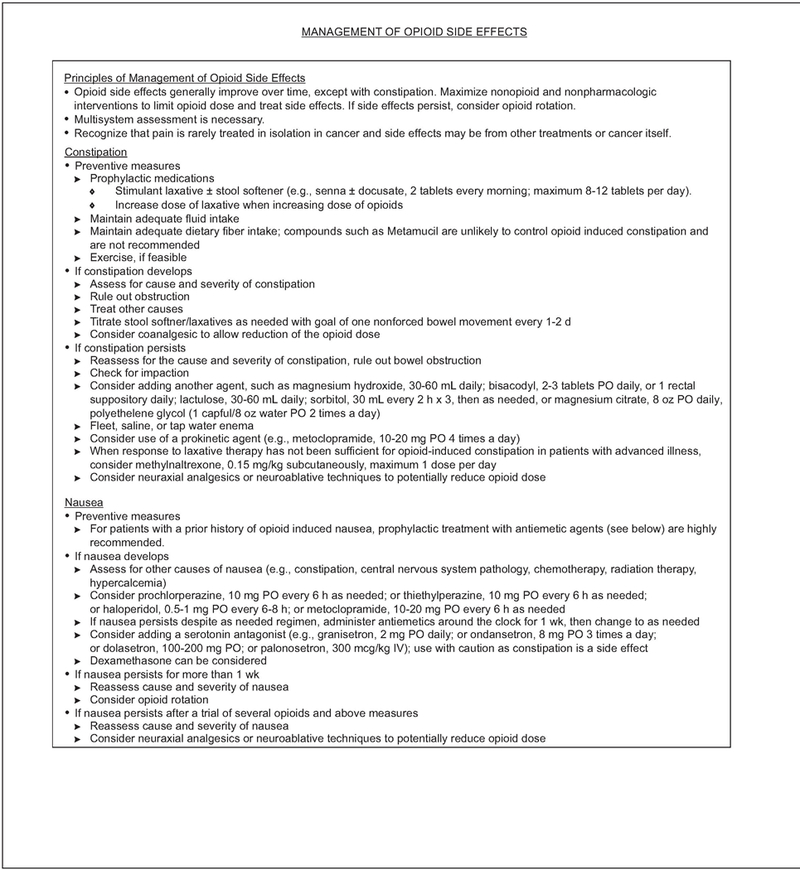

Treatment with opioids must be accompanied by a bowel regimen, and nonopioid analgesics as indicated. Details of prophylactic bowel regimens and antiemetics are provided on pages 1068 and 1069; management of these common opioid adverse effects should be started simultaneously with initiation of opioid therapy. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction should be anticipated and treated prophylactically with a stimulating laxative to increase bowel motility, with or without stool softeners as indicated.18

The pathways are similar for opioid-naïve patients who have a pain intensity rating between 4 and 6 at presentation and those who have a pain intensity rating of 7 to 10. The main differences include treatment beginning with slower titration of short-acting opioids.

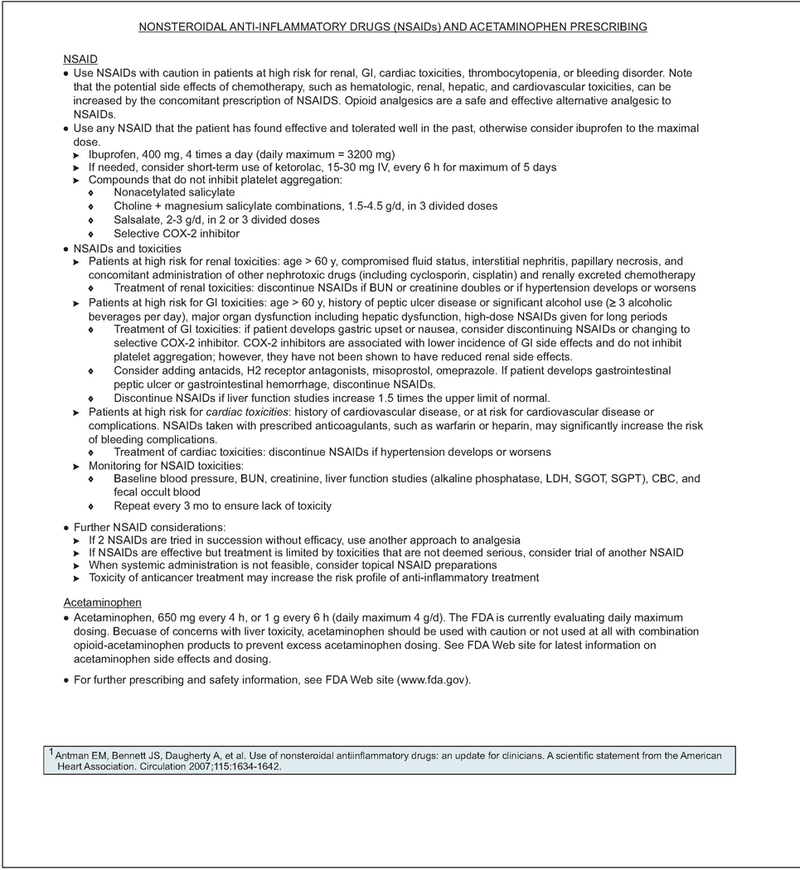

Opioid-naïve patients experiencing mild pain intensity (1–3) should undergo treatment with NSAIDs or acetaminophen, or treatment with consideration of slower titration of short-acting opioids.

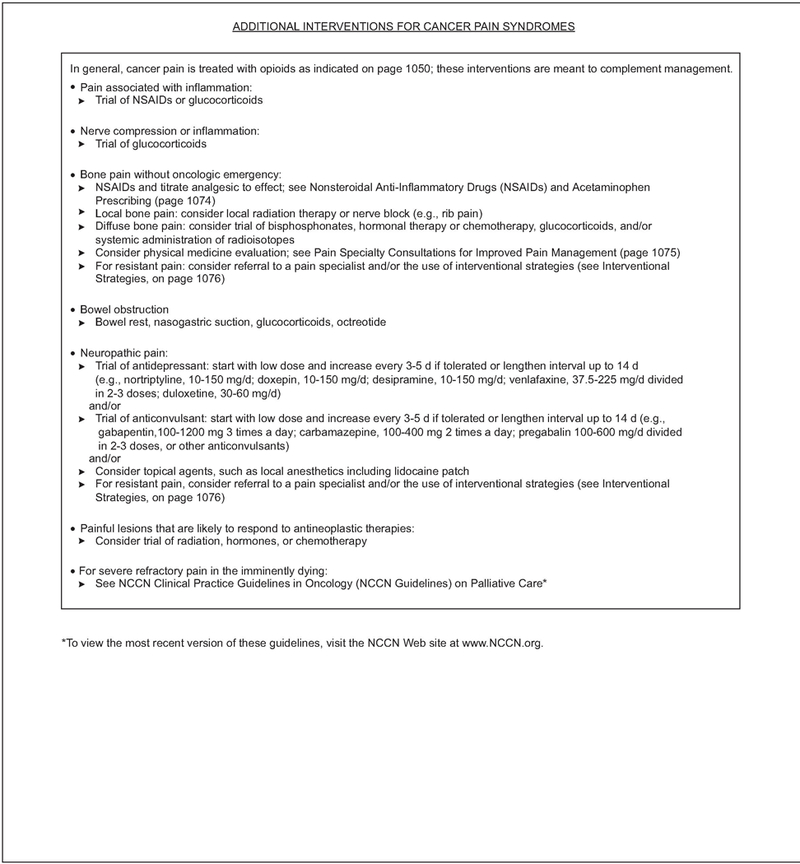

Addition of coanalgesics for specific pain syndromes should be considered for all groups of patients (see Additional Therapies, page 1082, and page 1070). Coanalgesics are drugs used to enhance the effects of opioids or NSAIDs.19

For all patients experiencing pain, health care providers should also provide psychosocial support and begin educational activities. Psychosocial support is needed to ensure that appropriate aid is provided to patients encountering common barriers to appropriate pain control (e.g., fear of addiction or side effects, inability to purchase opioids) or needing assistance in managing additional problems (e.g., depression, rapidly declining functional status; page 1071). Patients and families must be educated regarding pain management and related issues.

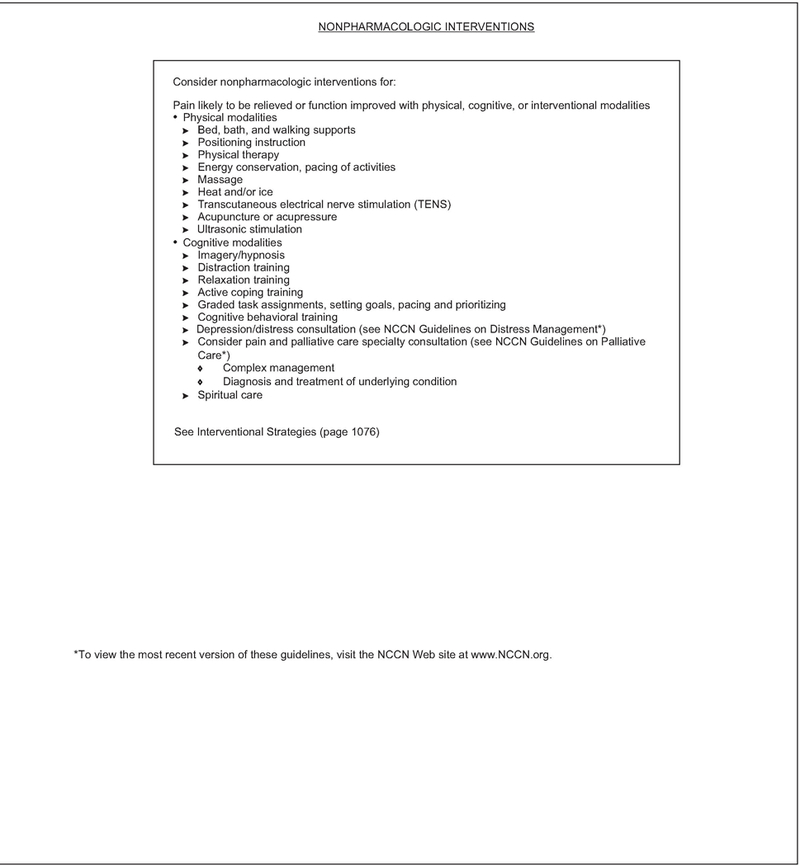

Although pharmacologic analgesics are the cornerstone of cancer pain management, they are not always adequate and are associated with many side effects, thus often necessitating the implementation of additional therapies or treatments. Optimal use of nonpharmacologic interventions may serve as valuable additions to pharmacologic interventions. A list of nonpharmacologic interventions that include physical and cognitive modalities are outlined on page 1073 and interventional strategies are discussed in the next section and on page 1076.

Opioid Principles, Prescribing, Titration, and Maintenance

Selecting an Appropriate Opioid:

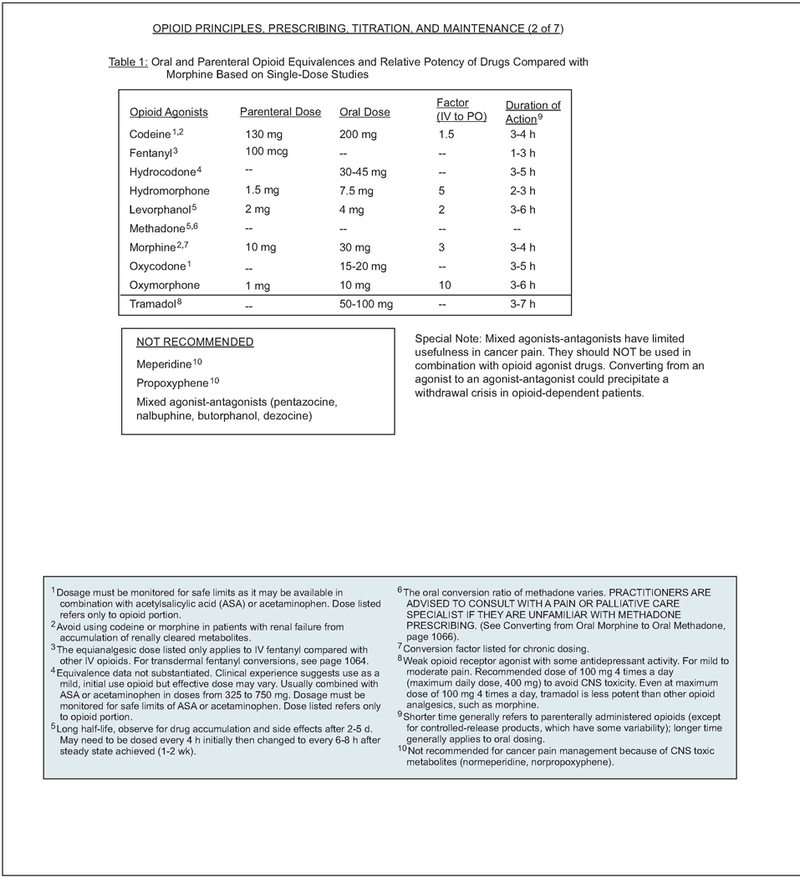

While starting therapy, attempts should be made to determine the underlying pain mechanism and diagnose the pain syndrome. Optimal analgesic selection will depend on the patient’s pain intensity, any current analgesic therapy, and concomitant medical illnesses. Morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, and oxycodone are the opioids commonly used in the United States. An individual approach should be used to determine opioid starting dose, frequency, and titration to achieve a balance between pain relief and medication adverse effects.

In patients not previously exposed to opioids, morphine is generally considered the standard preferred starting drug.20,21 An initial oral dose of 5 to 15 mg of morphine sulfate or equivalent or 2 to 5 mg of intravenous morphine sulfate or equivalent is recommended for opioid-naive patients.

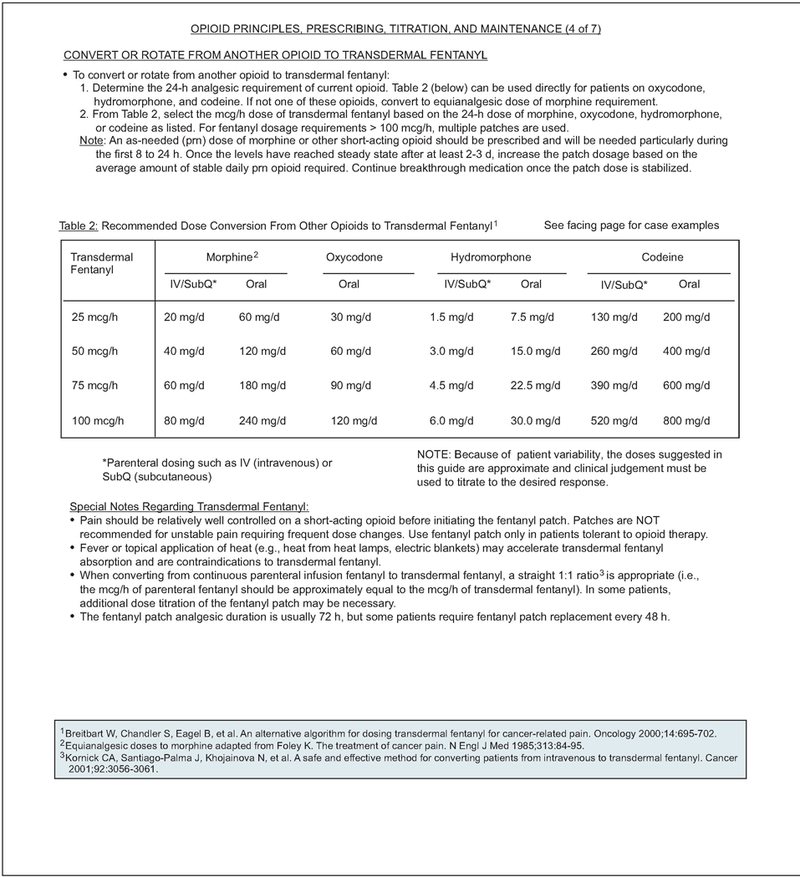

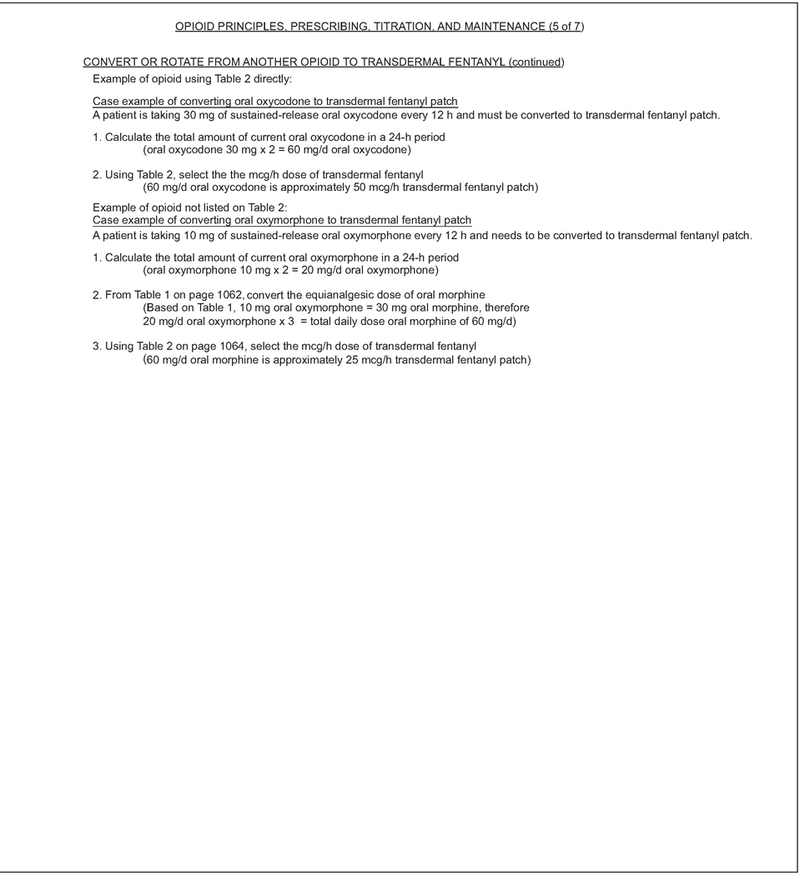

Pure agonists (e.g., codeine, oxycodone, oxy-morphone, fentanyl) are the most commonly used medications in the management of cancer pain. The opioid agonists with a short half-life (morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, and oxycodone) are preferred because they can be more easily titrated than the analgesics with a long half-life (methadone and levorphanol).22 Transdermal fentanyl is not indicated for rapid opioid titration and only should be recommended after pain is controlled by other opioids.23 Conversion from intravenous fentanyl to transdermal fentanyl can be accomplished effectively using a 1:1 conversion ratio24 (see pages 1061–1067).

Morphine should be avoided in patients with renal disease and hepatic insufficiency. Morphine-6-glucoronide, an active metabolite of morphine, contributes to analgesia and may worsen adverse effects as it accumulates in patients with renal insufficiency.25,26

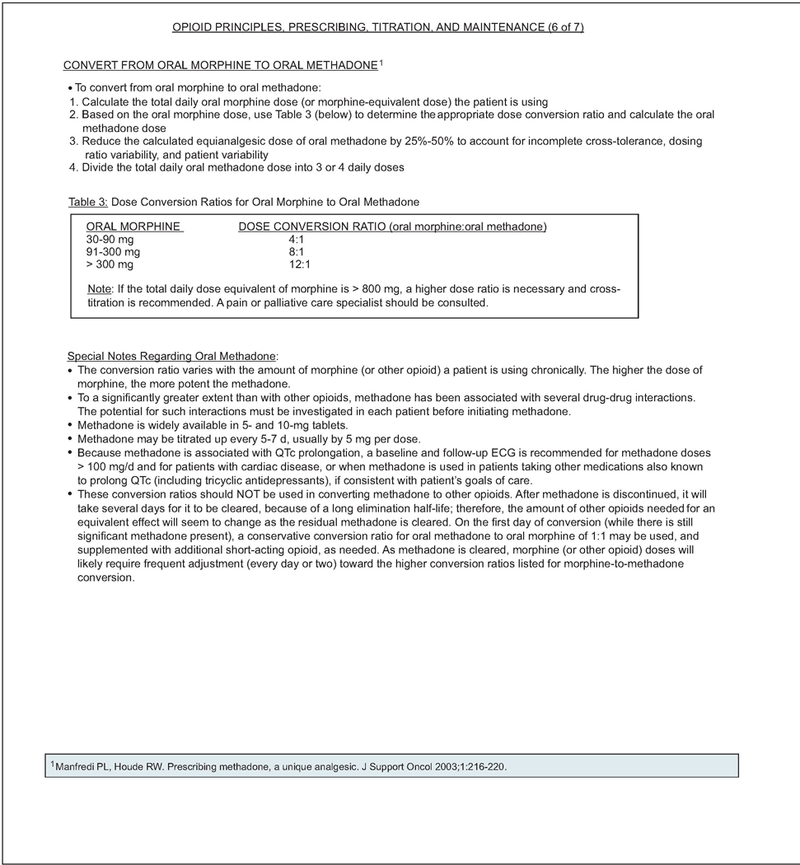

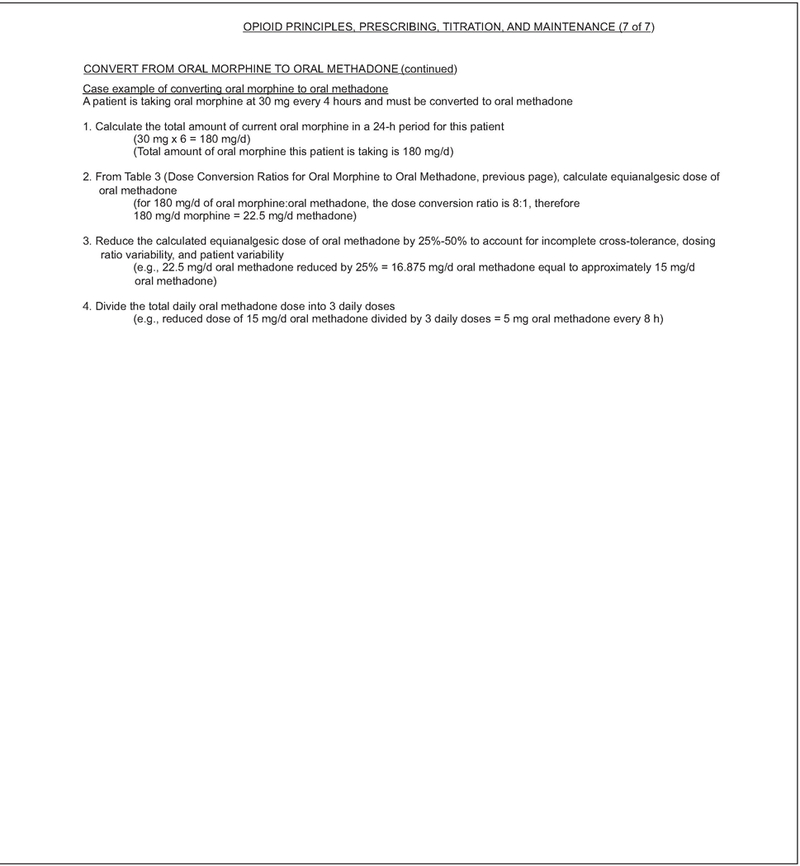

Individual variations in methadone pharmacokinetics (long half-life ranging from 8 to > 120 hours) make its use very difficult in patients with cancer.27 Because of its long half-life, high potency, and interindividual variations in pharmacokinetics, methadone should be started at lower-than-anticipated doses and slowly titrated upwards with provision of adequate short-acting breakthrough pain medications during the titration period. Consultation with a pain management specialist should be considered before its application.

Agents such as mixed agonist-antagonists (e.g., butorphanol, pentazocine), propoxyphene and meperidine, and placebos are not recommended for cancer patients. For treatment of severe pain, mixed agonist-antagonist drugs have limited efficacy and may precipitate opioid withdrawal if used in patients receiving pure opioid agonist analgesics. Meperidine and propoxyphene are contraindicated for chronic pain, especially in patients with impaired renal function or dehydration, because accumulation of renally cleared metabolites may result in neurotoxicity or cardiac arrhythmias.28 Use of placebo in the treatment of pain is unethical.

Propoxyphene is an inhibitor of the hepatic enzyme, CYP2D6.29,30 Because data suggest that CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants increase risk of recurrence in patients with breast cancer treated with tamoxifen31,32 (see Additional Therapies, page 1082), it is reasonable to assume that propoxyphene may have the same effect. Therefore, propoxyphene should be avoided in patients treated with tamoxifen. In general, propoxyphene should be avoided in cancer pain management because its risks far out-weigh any benefits.

Selecting a Route of Administration:

The least invasive, easiest, and safest route of opioid administration should be provided to ensure adequate analgesia.

Oral is the preferred route of administration for chronic opioid therapy.28,33,34 The oral route should be considered first in patients who can take oral medications unless a rapid onset of analgesia is required or the patient experiences side-effects associated with the oral administration. Continuous parenteral infusion, intravenous or subcutaneous, is recommended for patients who cannot swallow or absorb opioids enterally. Opioids, given parenterally, may produce fast and effective plasma concentrations compared with oral or transdermal opioids. Intravenous route is considered for faster analgesia because of the short lag-time between injection and effect (peak, 15 minutes) compared with oral dosing (peak, 60 minutes).35

The following methods of ongoing analgesic administration are widely used in clinical practice: around-the-clock, as-needed, and patient-controlled. Around-the-clock dosing is provided for continuous pain relief in patients with chronic pain, and a rescue dose of short-acting opioids should be provided as a subsequent treatment for pain that is not relieved (see pages 1061–1067). Opioids administered on an as-needed basis are for patients who have intermittent pain with pain-free intervals. The as-needed method is also used when rapid dose titration is required. The patient-controlled analgesia technique allows patients to control a device that delivers a bolus of analgesic on demand (according to, and limited by, parameters set by a physician).

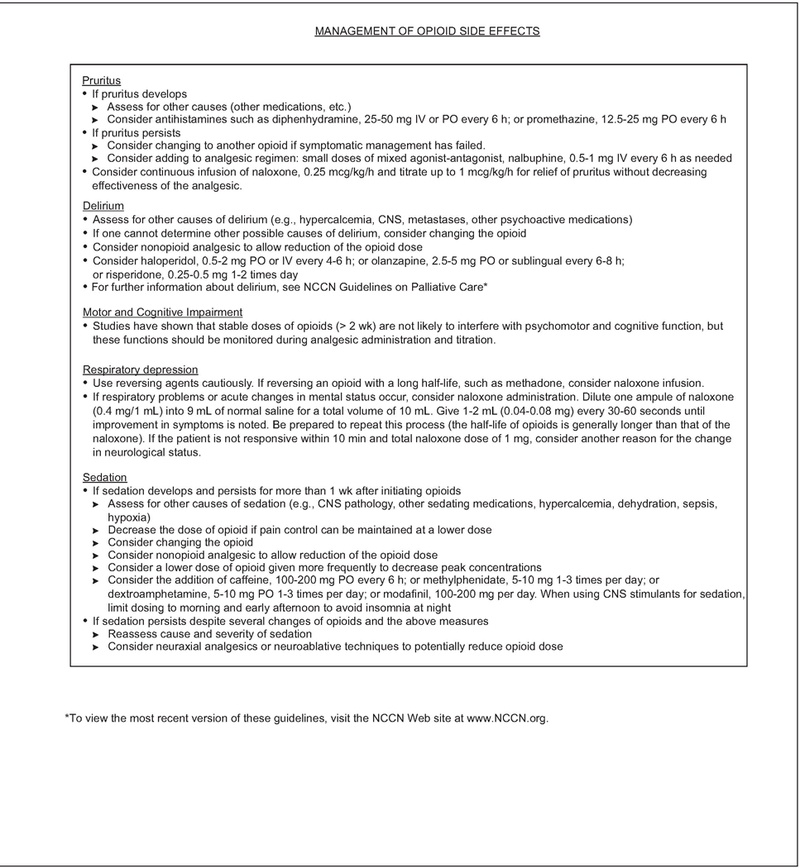

Opioid Adverse Effects

Constipation, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, delirium, respiratory depression, motor and cognitive impairment, and sedation are fairly common, especially when multiple agents are used.36–41 Each adverse effect requires a careful assessment and treatment strategy. Proper management is necessary to prevent and reduce analgesic adverse effects (see pages 1068 and 1069).36,42–50 Constipation can almost always be anticipated with opioid treatment; administration of prophylactic bowel regimen is recommended. However, evidence is limited on which to base the selection of the most appropriate bowel regimen. One study shows that adding a stool softener, docusate, to the laxative, sennosides, was less effective than the laxative alone.51 Therefore, the panel recommends a stimulant laxative with or without a stool softener. Details of prophylactic bowel regimens and other measures to prevent constipation, and antiemetics are provided on page 1068.

Opioid Rotation

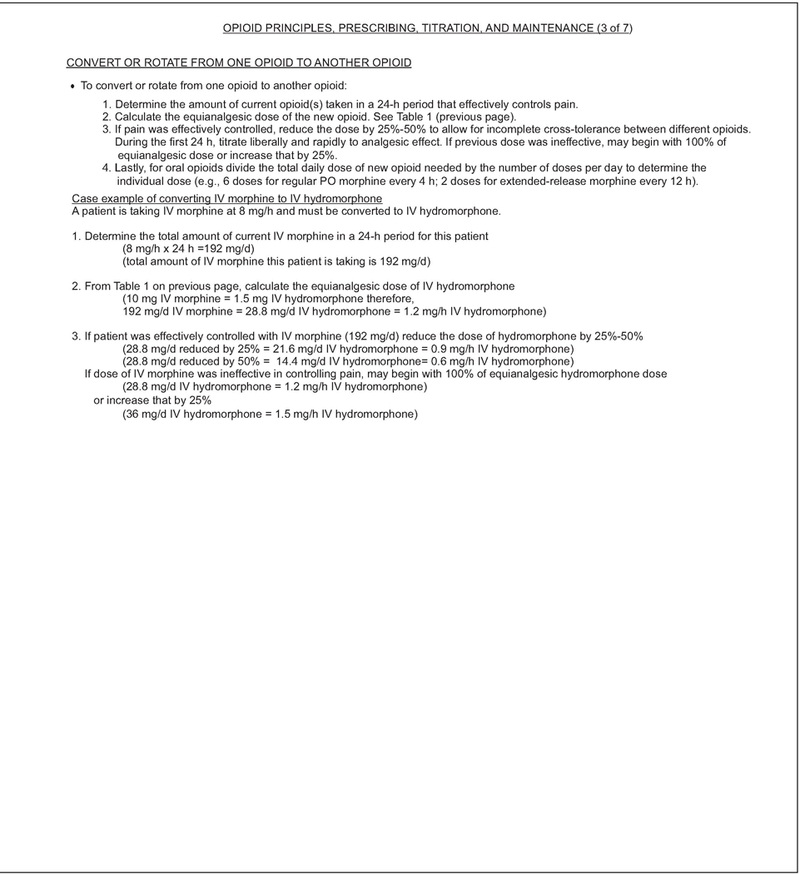

No single opioid is optimal for all patients.52 If opioid adverse effects are significant, an improved balance between analgesia and adverse effects might be achieved by changing to an equivalent dose of an alternative opioid. This approach is known as opioid rotation.36 Relative effectiveness is important to consider when switching between oral and parenteral routes to avoid subsequent over-or underdosing. Equianalgesic dose ratios, opioid titration and maintenance, and clinical examples of converting from one opioid to another are listed on pages 1061–1067.

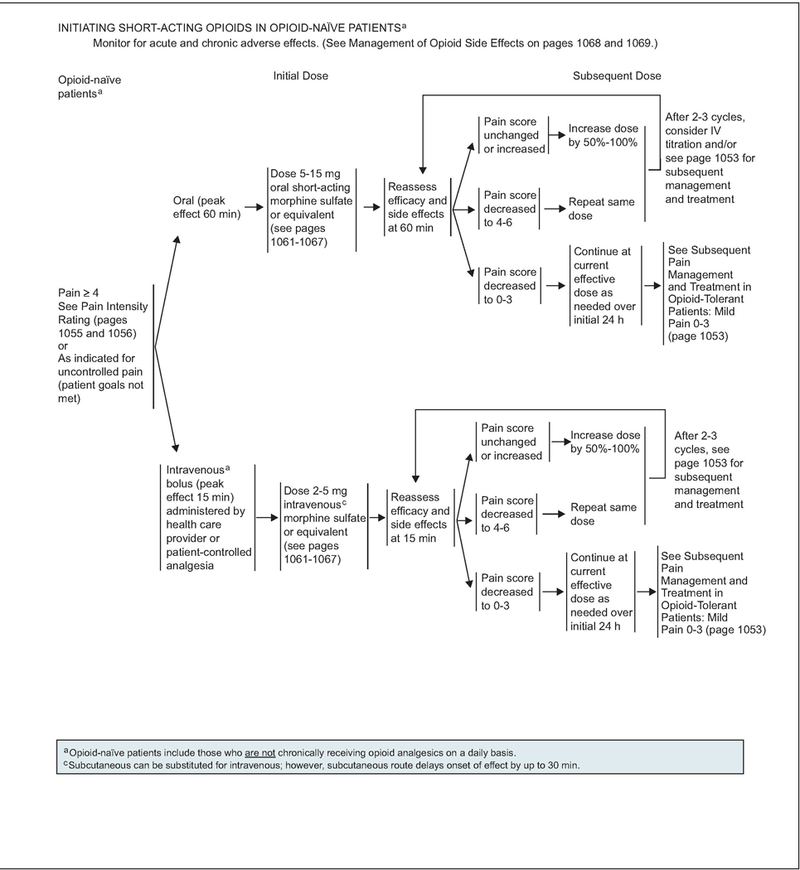

Initiating Short-Acting Opioids in Opioid-Naïve Patients

The route of administration of opioid (oral or intravenous) must be selected based on the needs of the patient.

For opioid-naïve patients experiencing a pain intensity of 4 or higher, or a pain intensity less than 4 whose goals of pain control and function are not met, an initial dose of 5 to 15 mg of oral morphine sulfate or 1 to 5 mg of intravenous morphine sulfate or equivalent is recommended (see page 1051). Assessment of efficacy and side effects should be performed every 60 minutes for orally administered opioids, and every 15 minutes for intravenous opioids, to determine a subsequent dose (see page 1051). If assessment shows that the pain score is unchanged or is increased, the panel recommends increasing the dose by 50% to 100% to achieve adequate analgesia. If the pain score decreases to 4 to 6, the same dose of opioid is repeated and reassessment is performed at 60 minutes for orally administered opioids and every 15 minutes for intravenously administered opioids. If inadequate response is seen in patients with moderate to severe pain on reassessment after 2 to 3 cycles of the opioid, changing the route of administration from oral to intravenous or subsequent management strategies (outlined on page 1053) can be considered. If the pain score decreases to 0 to 3, the current effective dose of opioid is administered as needed over an initial 24 hours before proceeding to subsequent management strategies (see page 1051).

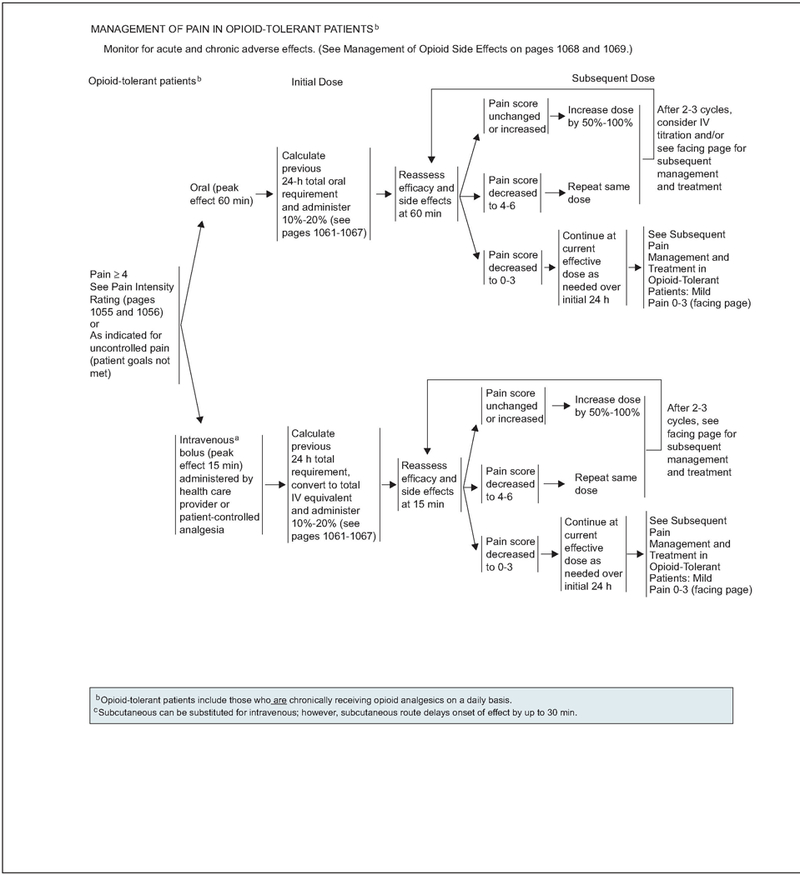

Management of Pain Not Related to an Oncologic Emergency in Opioid-Tolerant Patients

Opioid-tolerant patients take opioids chronically for pain relief. According to the FDA, opioid tolerant patients “are those who are taking at least: 60 mg oral morphine/day, 25 mcg transdermal fentanyl/ hour, 30 mg oral oxycodone/day, 8 mg oral hydro-morphone/day, 25 mg oral oxymorphone/day, or an equianalgesic dose of another opioid for one week or longer.”

In opioid-tolerant patients experiencing breakthrough pain intensity of 4 or greater, or less than 4 whose goals of pain control and function are not met, the previous 24-hour total oral or intravenous opioid requirement must be calculated and the new rescue dose increased by 10% to 20% to achieve adequate analgesia33,53 (see page 1052). Efficacy and side effects should be assessed every 60 minutes for orally administered opioids and every 15 minutes for intravenous opioids to determine a subsequent dose (see page 1052). On assessment, if the pain score is unchanged or increased, administration of 50% to 100% of the previous rescue dose of opioid is recommended. If the pain score decreases to 4 to 6, the same dose of opioid is repeated and reassessment is performed at 60 minutes for orally administered opioids and every 15 minutes for intravenously administered opioids. If the pain score remains unchanged on reassessment after 2 to 3 cycles of the opioid in patients with moderate to severe pain, changing the route of administration from oral to intravenous or alternate management strategies (outlined on page 1053) can be considered. If the pain score decreases to 0 to 3, the current effective dose of either oral or intravenous opioid is administered as needed over an initial 24 hours before proceeding to subsequent management strategies.

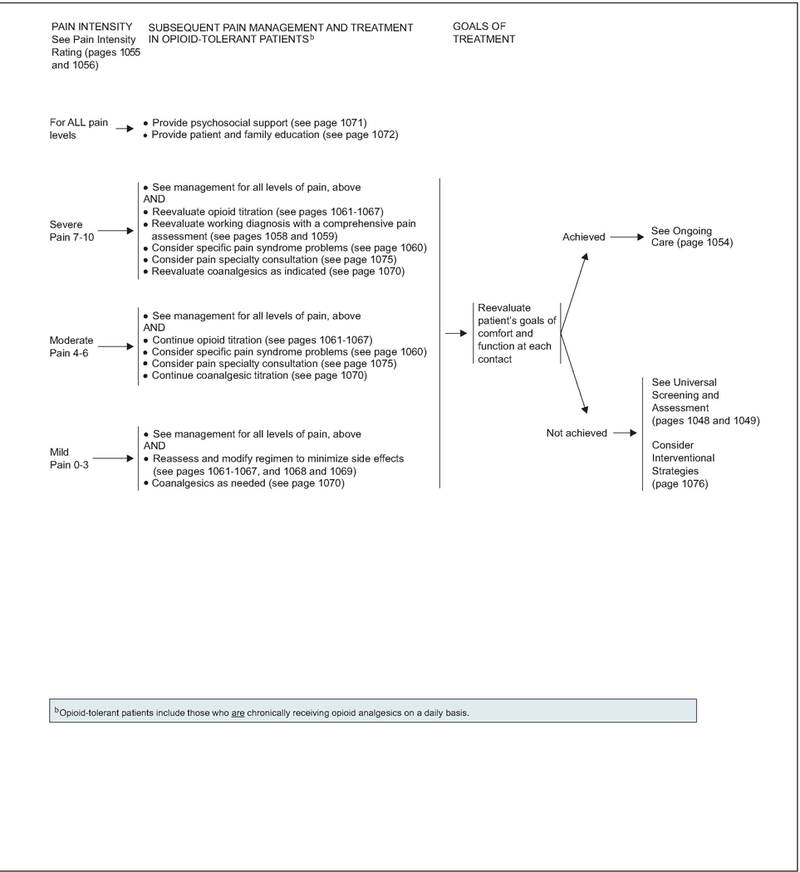

Subsequent Management of Pain in Opioid-Tolerant Patients

Subsequent treatment is based on the patient’s continued pain rating score (see page 1053). Approaches for all pain intensity levels must be coupled with psychosocial support and education for patients and their families.

If the pain at this time is severe, unchanged, or increased, the working diagnosis must be reevaluated and comprehensive pain assessment performed. For patients unable to tolerate dose escalation of their current opioid because of adverse effects, an alternate opioid must be considered (see pages 1061–1067). Addition of coanalgesics (see page 1070) should be reevaluated to either enhance the analgesic effect of the opioids or, in some cases, counter the adverse effects associated with the opioids.18 Given the multifaceted nature of cancer pain, additional interventions (see page 1060) for specific cancer pain syndromes and specialty consultation (see page 1075) must be considered to provide adequate analgesia.

If the patient is experiencing moderate pain intensity of 4 to 6 and adequate analgesic relief on their current opioid, the current titration of the opioid may be continued or increased. In addition, similar to patients experiencing severe pain, addition of coanalgesics (see page 1070), additional interventions for specific cancer pain syndromes (see page 1060), and specialty consultation must be considered (see page 1075).

For opioid-tolerant patients with mild pain who are experiencing adequate analgesia but intolerable or unmanageable side effects, the analgesic dose may be reduced by 25% of the current opioid dose (see page 1075). Addition of coanalgesics may be considered.

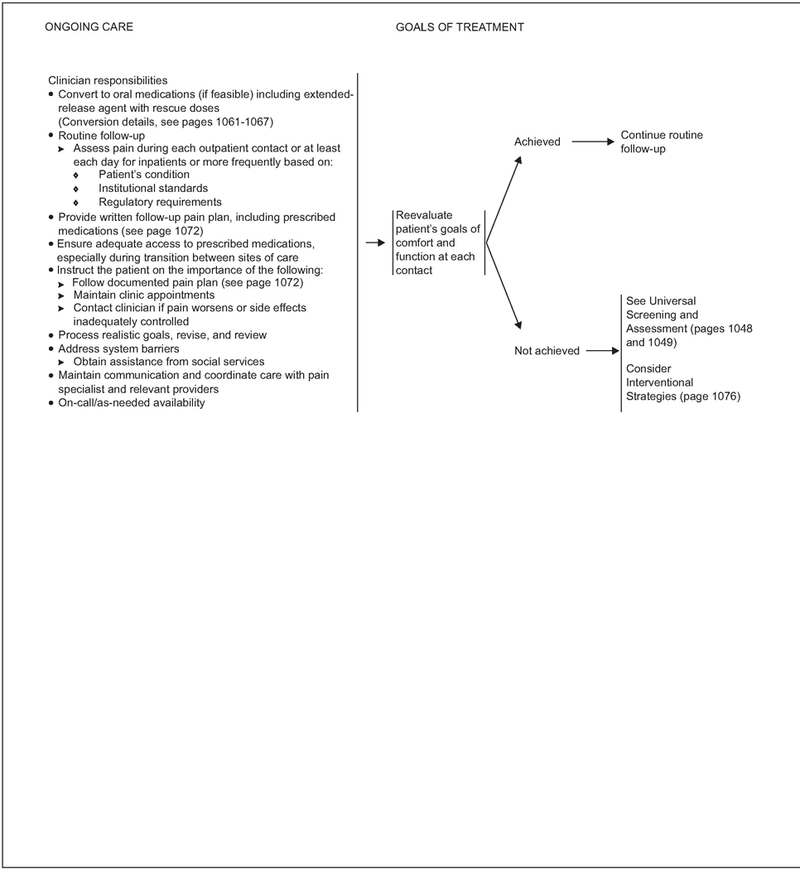

Ongoing Care

Although pain intensity ratings will be obtained frequently to evaluate opioid dose increases, a formal reevaluation to determine patient goals of comfort and function is mandated at each contact.

If an acceptable level of comfort and function has been achieved for the patients and 24-hour opioid requirement is stable, the panel recommends converting to an extended-release oral medication (if feasible) or other extended-release formulation (e.g., transdermal fentanyl) or long-acting agent (e.g., methadone; see page 1054). Subsequent treatment is based on the patient’s continued pain rating score. Rescue doses of the short-acting formulation of the same long-acting drug may be provided during maintenance therapy for the management of pain in cancer patients not experiencing relief with extended-release opioids.

Routine follow-up of inpatients should be performed during each outpatient contact, or at least each day, depending on patient conditions and institutional standards.

Patients should be provided with a written follow-up plan and instructed on the importance of adhering to the medication plan, maintaining clinic appointments, and following up with clinicians (see page 1072).

If an acceptable level of comfort and function has not been achieved, universal screening and assessment must be performed and additional strategies for pain relief considered.

Management of Procedure-Related Pain and Anxiety

Procedure-related pain represents an acute shortlived experience that may be accompanied by a great deal of anxiety (see page 1057). Procedures reported as painful include bone marrow aspirations; wound care; lumbar puncture; skin and bone marrow biopsies; intravenous, arterial, and central lines; and injections. Many of the data available on procedure-related pain are from studies on pediatric patients with cancer, which are then extrapolated to adults. Interventions to manage procedure-related pain should take into account the type of procedure, the anticipated level of pain, and other individual characteristics of the patients, such as age and physical condition. The interventions may be multimodal and may include pharmacologic and/or nonpharma-cologic approaches.

Local anesthetics can be used to manage procedure-related pain with sufficient time for effectiveness as per package insert. Examples of local anesthetics include lidocaine, prilocaine, and tetracaine. Physical approaches such as cutaneous warming, laser or jet injection, and ultrasound may accelerate the onset of cutaneous anesthesia. Sedatives may also be used. However, deep sedation and general anesthesia must be performed only by trained professionals. In addition, use of nonpharmacologic interventions listed on page 1073 may be valuable in managing procedure-related pain and anxiety. The major goal of nonpharmacologic interventions that include physical and cognitive modalities is to promote a sense of control, thereby increasing hope and reducing helplessness experienced by many patients with pain from cancer.

Patients usually tolerate procedures better when they know what to expect. Therefore, patients and family members should receive written instructions for managing the pain. Preprocedure patient education on procedure details and pain management strategies is essential. Patients and family members should receive written information regarding pain management options.

Interventional Strategies

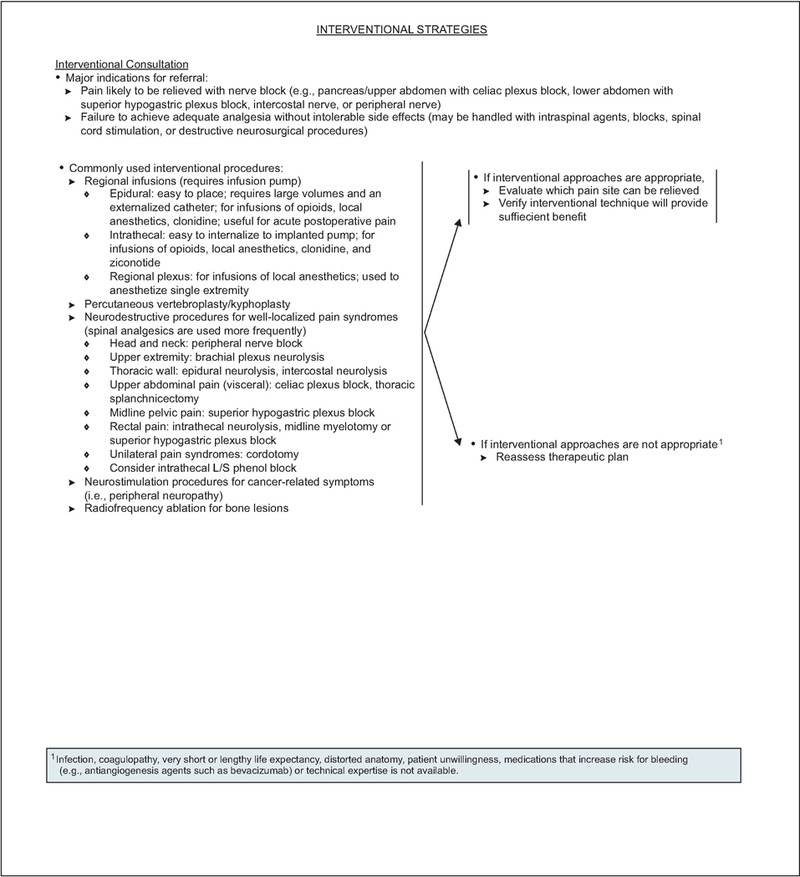

Some patients experience inadequate pain control despite pharmacologic therapy, or may not tolerate an opioid titration program because of side effects. Some patients may prefer procedural options over a chronic medication regimen. The major indications for referral for interventional strategies include pain that is likely to be relieved with nerve block (e.g., pancreas/upper abdomen with celiac plexus block, lower abdomen with superior hypogastric plexus block, intercostal nerve, or peripheral nerve) and/or patients failing to achieve adequate analgesia without intolerable side effects. For example, a patient with pancreatic cancer who was unable to tolerate opioids or experience adequate analgesia could be offered a celiac plexus block.

Several interventional strategies (see page 1076) are available for patients who do not experience adequate analgesia. Regional infusion of analgesics (epidural, intrathecal, and regional plexus) is one approach. This approach minimizes the distribution of drugs to receptors in the brain, potentially avoiding side effects of systemic administration. The intrathecal route of opioid administration should be considered in patients with intolerable sedation, confusion, and/or inadequate pain control with systemic opioid administration. This approach is a valuable tool to improve analgesia in patients experiencing pain in various anatomic locations (e.g., head and neck, upper and lower extremities, trunk).54 Neuroablative procedures used for well-localized pain syndromes (e.g., back pain from facet or sacroiliac joint arthropathy; visceral pain from abdominal or pelvic malignancy), such as percutaneous vertebroplasty/ kyphoplasty, neurostimulation procedures (i.e., for peripheral neuropathy), and radiofrequency ablation for bone lesions, have proven successful in managing pain (see page 1076), especially in patients unable to experience adequate analgesia without intolerable effects. In some cases, these techniques have been successfully used to eliminate or significantly reduce the level of pain, and/or may allow a significant decrease in systemic analgesics.

These interventional strategies are not appropriate in unwilling patients or those with infections, coagulopathy, or very short life expectancy. Furthermore, the experts performing the interventions must be made aware of any medications the patients are taking that might increase risk for bleeding (e.g., anticoagulants [warfarin, heparin], antiplatelet agents [clopidogrel, dipyridamole], antiangiogenesis agents [bevacizumab]). In these cases, the patient may have to be off the medication for an appropriate amount of time before the pain intervention is initiated and may need to continue to stay off the medication for a specified amount of time after the procedure. Interventions are not appropriate if technical expertise is not available.

Additional Therapies

Additional strategies specific to the pain situation can be considered. Specific recommendations for inflammatory pain, bone pain, nerve compression or inflammation, neuropathic pain, pain cause by bowel obstruction, and pain likely to respond to antineoplastic therapies are provided in the algorithm (see page 1060). Overall, neuropathic pain is less responsive to opioids than pain caused by other pathophysiologies.

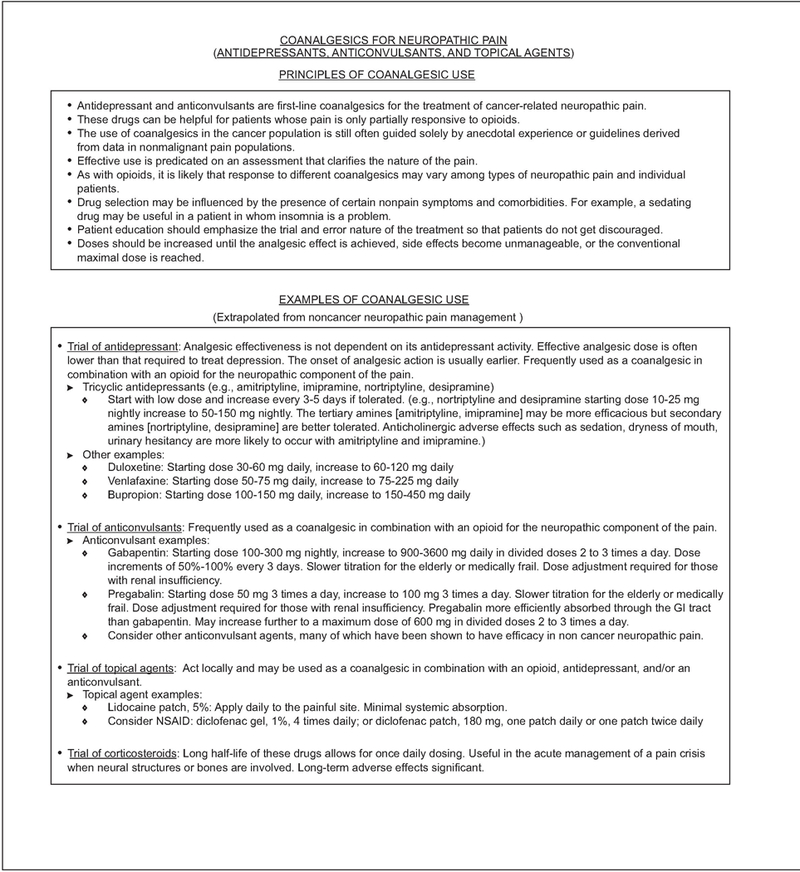

Other therapies, including specific nontraditional analgesic drugs, are usually indicated for neuropathic pain syndrome.55 For example, a patient with neuropathic pain who failed to gain sufficient relief from opioids would be given a coanalgesic.

Clinically, coanalgesics consist of a diverse range of drug classes, including anticonvulsants56 (e.g., ga-bapentin, pregabalin), antidepressants (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants), corticosteroids, and local anesthetics (e.g., topical lidocaine patch).

Several antidepressants are known inhibitors of hepatic drug metabolism through inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes, especially CYP2D6. Tamoxifen is an estrogen receptor blocker commonly used in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Tamoxifen undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, and inhibition of CYP2D6 decreases production of tamoxifen-active metabolites, potentially limiting tamoxifen efficacy. Clinical studies indicate increased risk of breast cancer recurrence in patients with breast cancer treated with tamoxifen and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants compared with those receiving tamoxifen alone.31,32 If concomitant use of an SSRI is required in patient receiving tamoxifen, use of a mild CY-P2D6 inhibitor (sertraline, citalopram, venlafaxine, escitalopram) may be preferred over a moderate-to-potent inhibitor (paroxetine, fluoxetine, fluvox-amine, bupropion, duloxetine).57

Coanalgesics are commonly used to help manage bone pain, neuropathic pain, and visceral pain, and to reduce systemic opioid requirement. They are particularly important in treating neuropathic pain that is resistant to opioids.58

Acetaminophen59; NSAIDs including selective COX-2 inhibitors; tricyclic antidepressants; anticonvulsant drugs; bisphosphonates; and hormonal therapy are among the most commonly used medications. The NSAID and acetaminophen prescribing guidelines are presented on page 1074. History of peptic ulcer disease, advanced age (> 60 years), male gender, and concurrent corticosteroid therapy should be considered before NSAID administration to prevent upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding and perforation. Well-tolerated proton pump inhibitors are recommended to reduce gastrointestinal side effects induced by NSAIDs. To prevent renal toxici-ties, NSAIDs should be prescribed with caution in patients who are older than 60 years or have compromised fluid status or renal insufficiency, or when given with concomitant administration of other nephrotoxic drugs and renally excreted chemotherapy.

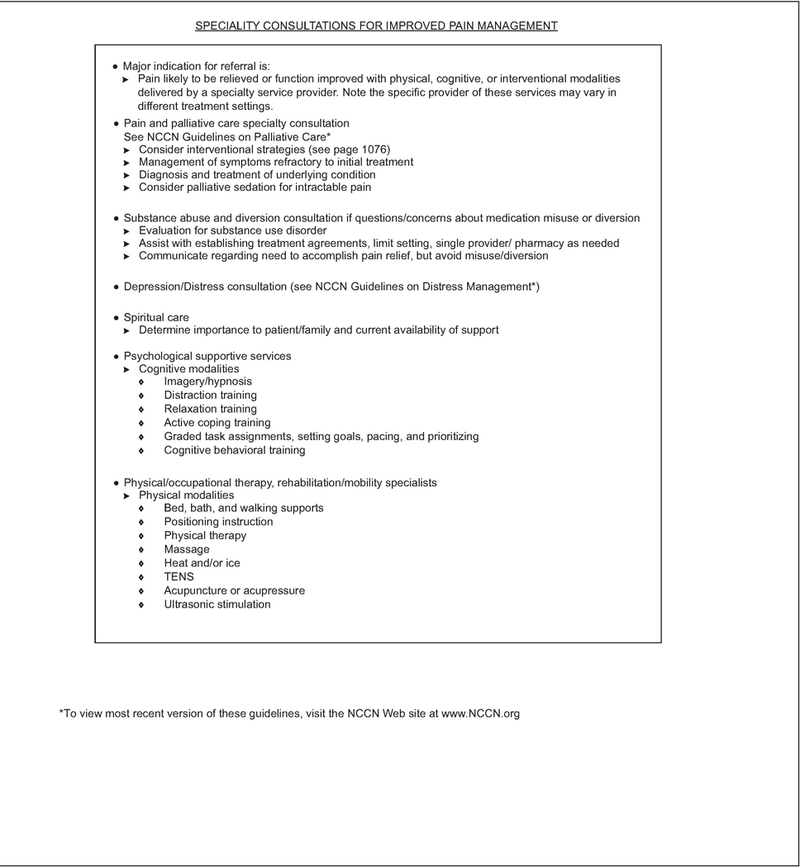

Nonpharmacologic specialty consultations for physical (e.g., massage, physical therapy) and cognitive modalities (e.g., hypnosis, relaxation) may provide extremely beneficial adjuncts to pharmacologic interventions (see page 1073).

Attention should also be focused on psychosocial support (see page 1071), providing education to patients and families (see page 1072), and reducing side effects of the opioid analgesics.

Continued pain ratings should be obtained and documented in patients’ medical records to ensure that the pain remains under good control and goals of treatment are achieved. Specialty consultations can be helpful in providing interventions to assist with difficult cancer pain problems (see page 1075). The major indication for referral to a specialty service provider is whether the pain is likely to be relieved or will help patients become functional in their daily activities. These modalities are delivered by a specialty service provider, and pain management is accomplished through establishing individualized goals and providing specific treatment and education for patients. The specialties include physical/occupational therapy and psychosocial supportive services, and other fields with expertise in interventional modalities.

Summary

In most patients, cancer pain can be successfully controlled with appropriate techniques and safe drugs. The overall approach to pain management encompassed in these guidelines is comprehensive. It is based on routine pain assessments, utilizes both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, and requires ongoing reevaluation of the patient. The NCCN Adult Cancer Pain Guidelines panel advises that cancer pain can be well controlled in the vast majority of patients if the algorithms presented are systematically applied, carefully monitored, and tailored to the needs of the individual patient.

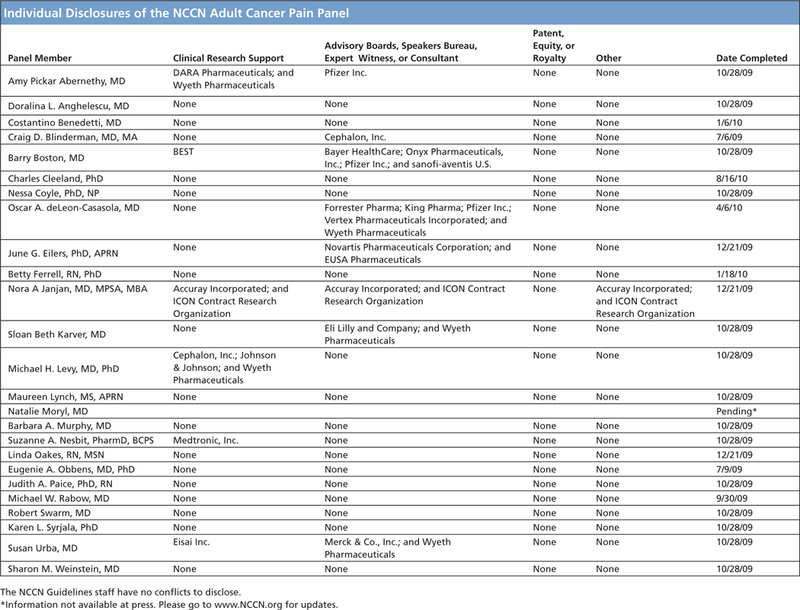

Individual Disclosures of the NCCN Adult Cancer Pain Panel.

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: The recommendation is based on high-level evidence (e.g., randomized controlled trials) and there is uniform NCCN consensus.

Category 2A: The recommendation is based on lower-level evidence and there is uniform NCCN consensus.

Category 2B: The recommendation is based on lower-level evidence and there is nonuniform NCCN consensus (but no major disagreement).

Category 3: The recommendation is based on any level of evidence but reflects major disagreement.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Please Note

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines™) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines™ is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way.

Disclosures for the NCCN Guidelines

Panel for Adult Cancer Pain

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines panel meeting, panel members disclosed any financial support they have received from industry. Through 2008, this information was published in an aggregate statement in JNCCN and online. Furthering NCCN’s commitment to public transparency, this disclosure process has now been expanded by listing all potential conflicts of interest respective to each individual expert panel member.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Guidelines on Adult Cancer Pain panel members can be found on page 1086. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures, including levels of compensation, are available on the NCCN Web site atwww.NCCN.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, please visitwww.NCCN.org.

NCCN Adult Cancer Pain Panel Members

*Robert Swarm, MD/Chairϕ£

Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine

Amy Pickar Abernethy, MD†£

Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center Doralina L. Anghelescu, MDϕ

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/

University of Tennessee Cancer Institute Costantino Benedetti, MDϕ£

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute Craig D. Blinderman, MD, MAÞ£

Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center Barry Boston, MD£†

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/

University of Tennessee Cancer Institute Charles Cleeland, PhDθ

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Nessa Coyle, PhD, NP£#

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Oscar A. deLeon-Casasola, MDϕ£

Roswell Park Cancer Institute June G. Eilers, PhD, APRN#

UNMC Eppley Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

Betty Ferrell, RN, PhD£#

City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center Nora A. Janjan, MD, MPSA, MBA§

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Sloan Beth Karver, MD£

H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute

Michael H. Levy, MD, PhD£†

Fox Chase Cancer Center

Maureen Lynch, MS, APRN£#

Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

Natalie Moryl, MDÞ£

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Barbara A. Murphy, MD£†

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

Suzanne A. Nesbit, PharmD, BCPSΣ

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at

Johns Hopkins

Linda Oakes, RN, MSN#

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/

University of Tennessee Cancer Institute

Eugenie A. Obbens, MD, PhD£ψ

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Judith A. Paice, PhD, RN£#

Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of

Northwestern University

Michael W. Rabow, MD£

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

Karen L. Syrjala, PhDθ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/

Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

Susan Urba, MD£†

University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center

Sharon M. Weinstein, MD£ψ

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

KEY:

*Writing Committee Member

Specialties: ϕAnesthesiology; £Supportive Care, Including Palliative, Pain Management, Pastoral Care, and Oncology Social Work; tMedical Oncology; †Internal Medicine; 0Psychiatry, Psychology, Including Health Behavior; #Nursing; §Radiotherapy/Radiation Oncology; ΣPharmacology; ψNeurology/Neuro-Oncology

Footnotes

Recommended Readings

Levy MH, Chwistek M, Mehta RS. Management of chronic pain in cancer survivors. Cancer J 2008;14:401–409.

Levy MH, Samuel TA. Management of cancer pain. Semin Oncol 2005;32:179–193.

Kochhar R, Legrand SB, Walsh D, et al. Opioids in cancer pain: common dosing errors. Oncology (Williston Park) 2003;17:571– 575; discussion 575–576, 579.

Ripamonti C, Zecca E, Bruera E. An update on the clinical use of methadone for cancer pain. Pain 1997;70:109–115.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

Contributor Information

Robert Swarm, Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.

Amy Pickar Abernethy, Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Doralina L. Anghelescu, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/ University of Tennessee Cancer Institute.

Costantino Benedetti, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute.

Craig D. Blinderman, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center.

Barry Boston, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/ University of Tennessee Cancer Institute.

Charles Cleeland, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Nessa Coyle, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Oscar A. deLeon-Casasola, Roswell Park Cancer Institute.

June G. Eilers, UNMC Eppley Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center.

Betty Ferrell, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Nora A. Janjan, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Sloan Beth Karver, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute.

Michael H. Levy, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Maureen Lynch, Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center.

Natalie Moryl, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Barbara A. Murphy, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

Suzanne A. Nesbit, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins.

Linda Oakes, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/ University of Tennessee Cancer Institute.

Eugenie A. Obbens, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Judith A. Paice, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

Michael W. Rabow, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Karen L. Syrjala, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/ Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

Susan Urba, University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Sharon M. Weinstein, Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah.

References

- 1.Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl 1986;3(Supp 1):226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MZ, Easley MK, Ellis C, et al. Cancer pain management and the JCAHO’s pain standards: an institutional challenge. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goudas LC, Bloch R, Gialeli-Goudas M, et al. The epidemiology of cancer pain. Cancer Invest 2005;23:182–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svendsen KB, Andersen S, Arnason S, et al. Breakthrough pain in malignant and non-malignant diseases: a review of prevalence, characteristics and mechanisms. Eur J Pain 2005;9:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med 1994;330:592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin LA, Hagen NA. Neuropathic pain in cancer patients: mechanisms, syndromes, and clinical controversies. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;14:99–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercadante S Malignant bone pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Pain 1997;69:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stjernsward J WHO cancer pain relief programme. Cancer Surv 1988;7:195–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stjernsward J, Colleau SM, Ventafridda V. The World Health Organization Cancer Pain and Palliative Care Program. Past, present, and future. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caraceni A, Weinstein SM. Classification of cancer pain syndromes. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001;15:1627–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewitt DJ. The management of pain in the oncology patient. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2001;28:819–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portenoy RK. Cancer pain. Epidemiology and syndromes. Cancer 1989;63:2298–2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, et al. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 2001;93:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, et al. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain 1995;61:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soetenga D, Frank J, Pellino TA. Assessment of the validity and reliability of the University of Wisconsin Children’s Hospital Pain scale for Preverbal and Nonverbal Children. Pediatr Nurs 1999;25:670–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Atiyyat HN. Cultural diversity and cancer pain. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2009;11:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ezenwa MO, Ameringer S, Ward SE, Serlin RC. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain management in the United States. J Nurs Scholarsh 2006;38:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain, 5th ed Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercadante SL, Berchovich M, Casuccio A, et al. A prospective randomized study of corticosteroids as adjuvant drugs to opioids in advanced cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2007;24:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klepstad P, Kaasa S, Borchgrevink PC. Start of oral morphine to cancer patients: effective serum morphine concentrations and contribution from morphine-6-glucuronide to the analgesia produced by morphine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000;55:713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klepstad P, Kaasa S, Skauge M, Borchgrevink PC. Pain intensity and side effects during titration of morphine to cancer patients using a fixed schedule dose escalation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2000;44:656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherny NI. The pharmacologic management of cancer pain. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:1499–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanks GW, Conno F, Cherny N, et al. Morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain: the EAPC recommendations. Br J Cancer 2001;84:587–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornick CA, Santiago-Palma J, Khojainova N, et al. A safe and effective method for converting cancer patients from intravenous to transdermal fentanyl. Cancer 2001;92:3056–3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiseo PJ, Thaler HT, Lapin J, et al. Morphine-6-glucuronide concentrations and opioid-related side effects: a survey in cancer patients. Pain 1995;61:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portenoy RK, Foley KM, Stulman J, et al. Plasma morphine and morphine-6-glucuronide during chronic morphine therapy for cancer pain: plasma profiles, steady-state concentrations and the consequences of renal failure. Pain 1991;47:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis MP, Homsi J. The importance of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP2D6 in palliative medicine. Support Care Cancer 2001;9:442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruera E, Kim HN. Cancer pain. JAMA 2003;290:2476–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bark in RL, Bark in SJ, Barkin DS. Propoxyphene (dextro- propoxyphene): a critical review of a weak opioid analgesic that should remain in antiquity. Am J Ther 2006;13:534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein DJ, Turk DC. Dextropropoxyphene: safety and efficacy in older patients. Drugs Aging 2005;22:419–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aubert R, Stanek EJ, Yao J, et al. Risk of breast cancer recurrence in women initiating tamoxifen with CYP2D6 inhibitors [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(Suppl 1):Abstract CRA508. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dezentje V, Van Blijderveen NJ, Gelderblom H, et al. Concomitant CYP2D6 inhibitor use and tamoxifen adherence in early-stage breast cancer: a pharmacoepidemiologic study [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(Suppl 1):Abstract CRA509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet 1999;353:1695–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens RA, Ghazi SM. Routes of opioid analgesic therapy in the management of cancer pain. Cancer Control 2000;7:132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris JT, Suresh Kumar K, Rajagopal MR. Intravenous morphine for rapid control of severe cancer pain. Palliat Med 2003;17:248– 256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNicol E, Horowicz-Mehler N, Fisk RA, et al. Management of opioid side effects in cancer-related and chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain 2003;4:231–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercadante S Comments on Wang et al., PAIN, 67 (1996) 407–416. Pain 1998;74:106–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercadante S Pathophysiology and treatment of opioid-related myoclonus in cancer patients. Pain 1998;74:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson RK, Weissman DE. Neuroexcitatory effects of opioids: patient assessment #57. J Palliat Med 2004;7:579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moryl N, Carver A, Foley KM. Pain and palliation In: Holland JF, Frei E, eds. Cancer Medicine. Vol. I7 Hamilton, ON: BC Decker Inc; 2006:1113–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moryl N, Obbens EA, Ozigbo OH, Kris MG. Analgesic effect of gefitinib in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. J Support Oncol 2006;4:111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boettger S, Breitbart W. Atypical antipsychotics in the management of delirium: a review of the empirical literature. Palliat Support Care 2005;3:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, et al. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruera E, Belzile M, Neumann C, et al. A double-blind, crossover study of controlled-re lease metoclopramide and placebo for the chronic nausea and dyspepsia of advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000;19:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Challoner KR, McCarron MM, Newton EJ. Pentazocine (Talwin) intoxication: report of 57 cases. J Emerg Med 1990;8:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katcher J, Walsh D. Opioid-induced itching: morphine sulfate and hydromorphone hydrochloride. J Pain Symptom Manage 1999;17:70–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marinella MA. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction complicated by cecal perforation in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. South Med J 1997;90:1023–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reissig JE, Rybarczyk AM. Pharmacologic treatment of opioid- induced sedation in chronic pain. Ann Pharmacother 2005;39:727– 731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarcatu D, Tamasdan C, Moryl N, Obbens E. Are we still scratching the surface? A case of intractable pruritus following systemic opioid analgesia. J Opioid Manag 2007;3:167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prommer E Modafinil: is it ready for prime time? J Opioid Manag 2006;2:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawley PH, Byeon JJ. A comparison of sennosides-based bowel protocols with and without docusate in hospitalized patients with cancer. J Palliat Med 2008;11:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slatkin NE. Opioid switching and rotation in primary care: implementation and clinical utility. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2133–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mercadante S, Arcuri E, Ferrera P, et al. Alternative treatments of breakthrough pain in patients receiving spinal analgesics for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenberg HS, Taren J, Ensminger WD, Doan K. Benefit from and tolerance to continuous intrathecal infusion of morphine for intractable cancer pain. J Neurosurg 1982;57:360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H, Lamer TJ, Rho RH, et al. Contemporary management of neuropathic pain for the primary care physician. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:1533–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lussier D, Huskey AG, Portenoy RK. Adjuvant analgesics in cancer pain management. Oncologist 2004;9:571–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin Y, Desta Z, Stearns V, et al. CYP2D6 genotype, antidepressant use, and tamoxifen metabolism during adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manfredi PL, Gonzales GR, Sady R, et al. Neuropathic pain in patients with cancer. J Palliat Care 2003;19:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stockler M, Vardy J, Pillai A, Warr D. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) improves pain and well-being in people with advanced cancer already receiving a strong opioid regimen: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3389–3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]