Abstract

Background.

Integrative research summarizing promotive and protective factors that reduce the effects of childhood abuse and neglect on pregnant women and their babies’ healthy functioning is needed.

Objective.

This narrative systematic review synthesized the quantitative literature on protective and promotive factors that support maternal mental health and maternal-infant bonding among women exposed to childhood adversity, including childhood abuse and neglect.

Methods.

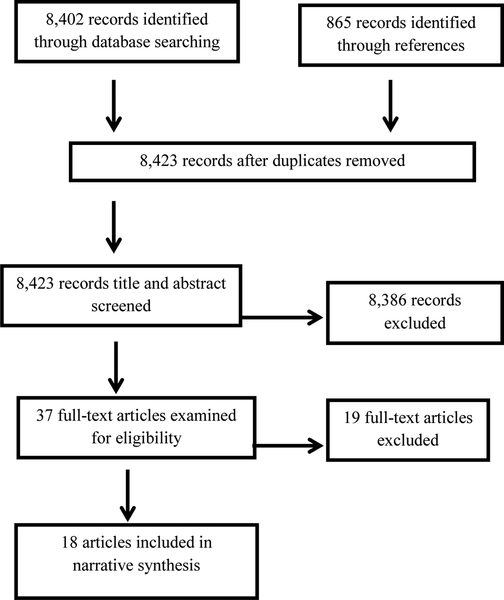

Using a comprehensive list of key terms related to the perinatal period, childhood adversity, and protective/promotive factors, 8,423 non-duplicated articles were identified through database searches in PsychInfo and Web of Science, and references in retrieved articles. Thirty-seven full text articles were inspected; of those 18 were included.

Results.

Protective and promotive factors fell into three categories: a) women’s internal capacities (e.g., self-esteem, coping ability), b) external early resources (e.g., positive childhood experiences) and c) external contemporaneous resources (e.g., social support). Although all three categories were associated with more resilient outcomes, external contemporaneous factors, and specifically, social support, were the most commonly-studied protective and/or promotive factor. Social support from family and romantic partners during the perinatal period was particularly protective for women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect and was examined across several dimensions of support and contexts.

Conclusions.

The presence of women’s internal capacities, and external early and contemporaneous resources help to foster more positive outcomes during the perinatal period for women with histories of childhood adversity. Future research should study co-occurring multilevel promotive and protective factors to inform how they integratively deter the intergenerational transmission of risk.

Keywords: protective factor, promotive factor, resilience, perinatal period, childhood adversity, developmental psychopathology

Childhood adversity, including childhood abuse and neglect, has detrimental long-term consequences on adulthood wellbeing, increasing risk for mental health diagnoses, physical health problems, and health risk behaviors (Arnow, 2004; Green et al., 2010; Norman et al., 2012; Springer, Sheridan, Kuo & Carnes, 2007; Teicher & Samson, 2013). Although the potential deleterious consequences of childhood abuse and neglect are well-established, all individuals who experience these adversities do not suffer negative outcomes (DuMont, Widom & Czaja, 2007; McGloin & Widom, 2001; Cicchetti, 2013). Therefore, an investigation of the mechanisms that confer long-term resilience following childhood adversity is essential, including the examination of both protective and promotive factors. Protective factors are influences that foster adaptive functioning in individuals at high levels of risk, whereas promotive factors support positive development across all levels of risk (Masten, 2014; Narayan, 2015). This distinction is particularly needed for understanding the nature of resilience processes during the perinatal period in women who have experienced childhood adversity.

The perinatal period is a transformative time characterized by psychological and biological changes during pregnancy, labor and, delivery (Narayan et al., 2017; Slade, Cohen, Sadler & Miller, 2009). Pregnancy can be a time of hope and excitement, as well as a period of increased concerns about bodily changes, childbirth, the child’s health, and changes in current relationships, all of which may lead to stress, particularly in those vulnerable to psychopathology or who have histories of childhood adversity (Seng, 2002). Adolescent pregnancy may introduce an additional vulnerability to stress during the perinatal period, as adolescents are working through the developmental tasks of adolescence (e.g., identity development, re-negotiation of family relationships) in addition to the transformation and reorganization inherent in the perinatal period. As pregnant women reorganize roles and relationships to prepare for parenting a new child, memories of their own childhood experiences of care become especially relevant (Slade et al., 2009). Negative memories of childhood caregivers, particularly those involving childhood abuse and neglect, coupled with increased stressors unique to the perinatal period, may be especially likely to result in symptomatology, negative caregiving expectations, and disrupted attributions about the baby (Narayan et al., 2017). Indeed, maternal experiences of childhood abuse and neglect are associated with maternal perinatal mental health problems (Buss et al., 2017; Choi & Sikkema, 2016; Racine et al., 2018a).

Maternal mental health problems and stress during pregnancy are associated with alterations to maternal stress physiology, preterm delivery, low birth weight, negative fetal and infant outcomes, and disrupted maternal-infant relationships (Buss et al., 2017; Lyons-Ruth & Block, 1996). Recent reviews outline the relation between maternal psychosocial stress during pregnancy and negative birth outcomes (e.g., low birth weight and premature birth), as well as effects on fetal brain development (e.g., manifested by infant emotion dysregulation and decreased cognitive ability) and disruptions to parenting during the postpartum period (e.g., insecure mother-infant attachment; Graignic-Philippe, Dayan, Chokron, Jacquet & Tordjman, 2014; Sandman, Davis, Buss & Glynn, 2012; Kingston, Tough & Whitfield, 2012). Given that the perinatal period is a critical transition with profound consequences for maternal and infant health, women with childhood adversity may be particularly at risk for the above negative outcomes (Narayan et al., 2017). It is essential to understand protective and promotive factors that curb the intergenerational transmission of risk in mothers with histories of childhood abuse and neglect to give families the healthiest possible start.

Much of the research on the long-term consequences of childhood abuse and neglect focuses on risk factors for disrupted maternal and infant wellbeing rather than on protective and promotive factors that might disrupt effects of childhood adversity and support maternal perinatal health (Sabina & Banyard, 2015). There is a growing literature on protective factors in adulthood (outside the perinatal period) that protect against the effects of childhood abuse and neglect. For instance, adults’ supportive relationships, adaptive coping skills, optimism, and intellectual ability promote resilience, evidenced by lower levels of psychopathology, substance abuse, and interpersonal problems, and higher self-esteem (Afifi & MacMillan, 2011; Domhardt, Münzer, Fegert & Goldbeck, 2015). However, only a few studies have evaluated the impact of different protective and promotive factors during the perinatal period in women who have experienced childhood adversity, including childhood abuse and neglect. The current narrative systematic review synthesized the empirical literature on positive perinatal influences that support maternal and infant outcomes during the perinatal period (defined as pregnancy through three years post-partum) for women with childhood adversity.

Resilience during the Perinatal Period: A Developmental Psychopathology Framework

Developmental psychopathology is an interdisciplinary framework centered on understanding the origins of and individual differences in typical and atypical development by integrating a life-course perspective, the role of contextual factors, and resilience (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Particularly important to this review, developmental psychopathology posits that early experiences, such as childhood abuse and neglect, have enduring effects on developmental pathways spanning the life course, including lifespan transitions (Slade et al., 2009; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). The perinatal period represents a major lifespan transition for women and a critical set of early experiences for an infant (beginning in utero) and a mother (representing her first caregiving experiences for this particular child), making it a unique window to study the function of protective and promotive factors. Importantly, the same stressful life events and/or positive influenes may result in a variety of developmental trajectories across different individuals, reflecting multifinality (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996), with adaptation following stressful early experiences typically being possible (Masten, 2014; Narayan, 2015; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984).

Developmental psychopathology conceptualizes resilience as a dynamic process involving multiple environmental systems and domains of functioning, resulting in adaptation in the face of risk or adversity (Masten, 2014; Narayan, 2015). A variety of outcomes can reflect more resilient functioning following adversity, including showing low levels of psychopathology; meeting academic, occupational, or familial expectations; and maintaining positive social relationships (DuMont et al., 2007; Sabina & Banyard, 2015). Furthermore, factors that foster more resilient functioning can be categorized into protective factors versus promotive factors. Because protective factors support adaptive functioning particularly at high levels of risk, they are typically illustrated by moderation or interaction effects. Alternatively, promotive factors foster positive development across both low and high levels of risk and are typically evident by direct, or main effects (Masten, 2014; Narayan, 2015).

It is important to understand both protective and promotive effects to elucidate the mechanisms through which resilience is fostered in different contexts. Both promotive and protective factors can exist at several levels including individual factors (e.g., coping), family factors (e.g., positive parenting) and broader contextual or environmental factors (e.g., social support or positive neighborhood characteristics; Cicchetti, 2013; Masten, 2014). Moreover, one factor (e.g., positive parenting) could have both promotive and protective effects if it is generally helpful for most individuals regardless of the level of risk, but also particularly beneficial as the level of risk rises (Masten, 2014; Narayan, 2015). Conceptually, promotive and protective factors coexist and interact at multiple levels within individuals, families, communities, and societies to simultaneously interrupt the negative effects of childhood adversity (Masten, 2014; Sabina & Banyard, 2015). Thus, the current multilevel priorities of contemporary resilience research provide a useful framework for evaluating the studies in this review.

The Current Review

This review synthesized quantitative literature on perinatal promotive and protective factors that support maternal and infant adaptation in the context of maternal history of childhood adversity. According to a multilevel resilience approach, promotive and protective factors were organized into three categories: a) internal capacities (e.g., self-esteem), b) external early resources (e.g., positive childhood experiences with caregivers despite or during adversity) and c) external contemporaneous resources (e.g., current social support).

Method

This review was guided by the PRISMA Statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & PRISMA Group, 2009). A number of inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified prior to conducting the literature search. Included studies were required to be quantitative, empirical, and published in peer-reviewed journals. Studies had to investigate at least one protective/promotive factor and examine its influence on maternal or infant outcomes during pregnancy or postpartum (within the first three years) for mothers exposed to childhood adversity (e.g., childhood abuse and neglect, other early traumatic events or poverty). Studies were required to operationalize promotive and protective variables as positive influences rather than exclusively measuring risk factors. For example, studies that measured absence of “intimate partner violence” were not included because we did not consider the absence of risk factors to be equivalent to the presence of positive influences. Excluded studies were those that (a) did not investigate a promotive/protective factor, (b) did not include participants who reported childhood adversity, (c) were qualitative, (d) measured maternal or infant outcomes beyond the first 3 years postpartum, or (e) were intervention studies. The latter was an exclusion criterion because this is the first review we are aware of to synthesize empirical research on perinatal promotive and protective factors. Thus, it seemed important to first comprehensively document resilience processes in basic research studies, with the goal to inform prevention and intervention research.

This study utilized search terms related to pregnancy and the postpartum periods; the process of promoting and/or protecting or buffering; childhood; and adversity. The following search string was applied in PsychInfo and Web of Science for articles published since 1980: [(pregnan* or prenatal or antenatal or perinatal) AND (buffer* or promot* or protect* or positive or support* or resilien* or moderat*) AND child* AND (advers* or abus* or trauma* or poverty or maltreat* or violen* or neglect)]. All literature searches were conducted in June 2018. Additional articles were identified by reviewing references in retrieved articles.

Using these criteria, 8,402 records were identified through database searches, and 865 records were identified through reviewing references in retrieved articles (see Figure 1). After duplicates were removed, 8,423 records remained. Article titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. The main reason for discarding records at this screening stage was because they evaluated risk factors but did not assess for promotive or protective factors. Then, 37 full-text articles were inspected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 19 were excluded for the following reasons: also did not measure a promotive/protective factor (n = 6), did not measure a childhood adversity (n = 4), measured the absence of risk rather than the presence of a positive influence (n = 3), measured the outcome more than three years after the birth of the child (n = 1), collected qualitative data only (n = 1), or utilized an intervention study design (n = 4). Raters carefully tracked the reasons why full-text inspected articles were excluded to ensure they were applying inclusion and exclusion criteria consistently.

Figure 1.

Data Extraction

Results

Description of Studies

Eighteen studies were included in the final review. Research on this topic began in the early 2000s. The earliest included study was published in 2001, despite searching for articles beginning in 1980. Interest has grown rapidly in recent years, with the majority of studies (n = 12) published since 2013. Included studies were conducted in the United States (n =13), Canada (n = 2), Germany (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), and Chile (n = 1). All studies were conducted in developed countries, classified as having “very high human development” by the United Nations Human Development Index. However, within these economically developed countries, 72% (n = 13) of studies focused on sample populations which were predominantly non-white and/or low-income (see Appendix A for detailed participant sociodemographic information for the included studies). The weighted mean age of mothers across studies was 26 years old. Four studies focused exclusively on pregnant adolescents (Bartlett & Easterbrooks, 2015; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Milan et al., 2004; Osborne & Rhodes, 2001). Most participants were recruited through community health centers, clinics, or hospitals. Sample sizes ranged from 57 to 1,994, with a mean of 412 participants (SD = 510).

Types of Childhood Adversity

All studies (n = 18) assessed at least one type of childhood abuse and/or neglect. Two studies assessed sexual abuse only (Leeners et al., 2016; Osborne & Rhodes, 2001) and one study assessed physical abuse only (Milan et al., 2004). Eight studies assessed multiple types of abuse or neglect, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect.

Seven studies assessed other experiences of adversity in addition to childhood abuse and neglect. One of the seven studies assessed exposure to domestic violence (Bublitz et al., 2014). Another study additionally assessed low childhood socioeconomic status (Mitchell et al., 2018). Three of the seven studies assessed adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including childhood abuse and neglect, as well as family dysfunction (Chung et al., 2008; Narayan et al., 2018; Racine et al., 2018b). Two of the seven studies assessed adversity as a composite of childhood and adulthood experiences (Easterbrooks et al., 2011; Guyon-Harris et al., 2017) and were included because childhood abuse and neglect played a major role in their adversity calculations.

Four of the 18 studies were judged to meet our review criteria even though only some of the participants had experienced childhood adversity (Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Olhaberry et al., 2014; Seng et al., 2013). Although these studies did not test associations within the subsample of women exposed to childhood adversity specifically, they do help to identify promotive factors that support positive development across levels of risk for subgroups of women with childhood adversity and thus were included in the analyses.

Types of Maternal Outcomes

Maternal outcomes in the 18 included studies could be categorized into three domains of functioning: maternal mental health (e.g., depressive symptoms) (n = 9), maternal health/physiology, including biological health and health care utilization (e.g., cortisol awakening response; perinatal care) (n = 5), and mother-child relationships (e.g. infant attachment) (n = 5). One of these studies assessed both maternal mental health and the mother-child relationship (Seng et al., 2013). Within the domain of maternal mental health, eight of the nine studies assessed maternal depressive symptoms, either alone or in addition to other symptomatology. Although not expected a priori, the variety of outcomes included in this review highlights the dynamic and multifaceted illustrations of resilience, which is a hallmark of the developmental psychopathology perspective.

Types of Protective/Promotive Factors

Identified protective and/or promotive factors were categorized into three domains: mothers’ internal cognitive/psychological capacities (e.g., self-esteem; n = 4), external early resources (e.g., positive childhood experiences; n = 3), and external contemporaneous resources (e.g., social support; n = 14). These broad domains exemplify the resilience principle of developmental psychopathology, in that resilience is a dynamic process operating at multiple levels of the human ecology and throughout the lifespan. Of the studies described above, one study examined both external early and external contemporaneous resources (Bartlett & Easterbrooks, 2015) and two studies examined both internal cognitive/psychological capacities and external contemporaneous resources (Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013). Results of the 18 studies are briefly described below and comprehensively in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies Organized by Protective and Promotive Factor Category

| Study | N | Population characteristics | Type of childhood adversity | Measures of childhood adversity | Promotive/Protective factor (s) | Prenatal or postpartum assessment | Outcome(s) of interest | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Cognitive/Psychological Capacities | ||||||||

| Berthelot et al. (2015) | 57 | Predominately low-income, white adults | Lack of parental care (neglect and antipathy), parental physical abuse, and sexual abuse from any adult before age 17 | Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA) interview | Reflective functioning (mentalization) regarding general and trauma specific relationships | Postpartum (17 months) | Infant attachment | Mothers with high trauma-related reflective functioning had infants with predominantly organized attachment strategies, whereas 2/3 of mothers with low trauma-related reflective functioning had infants with attachment disorganization. |

| Leigh & Milgrom (2008) | 367 | Australian pregnant women | Emotional, sexual, & physical abuse during childhood | Extracted from Demographics & Psychosocial Risk Factors Questionnaire | Self-esteem | Prenatal (26–34 weeks) & Postpartum (10–12 weeks) | Depressive symptoms | Higher self-esteem was associated with fewer antenatal depressive symptoms. |

| Meltzer-Brody et al. (2013) | 187 | Predominately low-income, racial and ethnic-minority pregnant adolescents | Adolescents’ reported history of neglect and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse | Trauma history interview | Maternal selfefficacy, positive view of the pregnancy | Prenatal (2nd or 3rd trimester) & Postpartum (6 weeks) | Depressive symptoms | Maternal self-efficacy and positive views of the pregnancy were associated with fewer prenatal depressive symptoms. Positive views of the pregnancy were also associated with fewer postnatal depressive symptoms. |

| Sexton et al. (2015) | 214 | Adults | Emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect before age 17 | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) | Ability to cope with stress (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale) | Postpartum (6 months) | Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), PTSD | Ability to cope with stress moderated the relation between childhood abuse/neglect and PTSD, as well as the relation between childhood abuse/neglect and MDD. Among mothers with high levels of childhood abuse/neglect, those with high ability to cope with stress had fewer MDD and PTSD diagnoses, compared to mothers with low ability to cope with stress. |

| External Early Childhood Resources | ||||||||

| Bartlett & Easterbrooks (2015) | 447 | Predominately low income, ethnic-minority adolescents | Physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect before age 18 | CPS substantiated | Positive maternal care and involvement | Postpartum (average 11.95 months) | Infant neglect (by any perpetrator, CPS substantiated), maternal parenting empathy | Positive care in childhood did not significantly moderate the relation between history of childhood neglect, and maternal parenting empathy or neglect of her infant. |

| Chung et al. (2008) | 1476 | Predominately low-income, African American adults | Verbal hostility, physical and sexual abuse, domestic violence, witnessing a shooting, having a guardian in trouble with the law or in jail, and homelessness before age 16 | 7-item Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) | Positive influences in childhood (PICs), including positive parental ‘relationships and physical and verbal affection | Prenatal (first prenatal care visit) | Depressive symptoms | Greater positive influences in childhood were associated with fewer prenatal depressive symptoms. Among women with a history of childhood sexual abuse or a parent who had gotten in trouble with the law, those who had a positive maternal relationship in childhood or who reported often receiving hugs were less likely to have depressive symptoms. |

| Narayan et al. (2018) | 101 | Predominately low-income, ethnic- minority adults | Maltreatment (verbal/emotional, physical and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect) and

family dysfunction (domestic violence, parental divorce/separation, substance use, ^ mental illness, and incarceration) before age 18 |

10-item Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) scale | Benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale | Prenatal (2nd or 3rd trimester) | PTSD, stressful life events during pregnancy | Among mothers with high levels of ACEs, those who also had high levels of benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) reported fewer PTSD symptoms and stressful life events compared to women with high levels of ACEs but lower BCEs. |

| External Contemporaneous Resources | ||||||||

| Bartlett & Easterbrooks (2015) | 447 | Predominately low-income, ethnic-minority adolescents | Physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect before age 18 | CPS substantiated | Social support frequency and dependability | Postpartum (average 11.95 months) | Infant neglect (by any perpetrator, CPS substantiated), maternal parenting empathy | Greater frequency of social support was associated with lower rates of infant neglect. Social support also moderated the association between history of childhood neglect and maternal empathy. Mothers with a history of childhood neglect demonstrated higher parenting empathy when they had frequent access to social support; whereas there was no effect of social support among mothers without a history of childhood neglect. |

| Bell & Seng (2013) | 467 | Predominately low-income adults | Physical, sexual, emotional abuse or physical neglect before age 16 | Life Stressor Checklist (LSC) | Mental health services use prior to pregnancy, alliance with health care provider during pregnancy | Prenatal (across pregnancy) | Adequate prenatal care (at least nine visits, with the first visit occurring before 14 weeks) | Mothers who had utilized mental health services prior to pregnancy and had stronger alliance with the health care provider during pregnancy were more likely to receive adequate prenatal care. |

| Bublitz et al. (2014) | 185 | Predominately ethnic-minority adults | Sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect or witnessed domestic violence before age 18 | 15-item Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) scale | Supportive current family environment | Prenatal (25, 29, & 35 weeks) | Cortisol awakening response (CAR) Trajectories across pregnancy |

Family functioning moderated the association between childhood sexual abuse and change in CAR over pregnancy. Mothers who reported higher support from family displayed more typical CAR across pregnancy. |

| Easterbro oks et al. (2011) | 361 | Predominately low-income, ethnic-minority adolescents and adults | Childhood experiences (psychological and physical abuse, parental nurturance) and current circumstances (neighborhood poverty, financial stress, poor indoor and outdoor living conditions) | Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS), Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI), current poverty level by census data, financial stress measure, Family Assessment Form for indoor & outdoor living conditions | Social network | Postpartum (average 20 months; range: 11.5months – 3 years) | Lack of perpetration of child maltreatment | Among mothers experiencing high levels of childhood adversity or high childhood and current adversity, those who did not perpetrate child maltreatment against their offspring were less likely to live with their family of origin and less likely to rely on their own mother for emotional or caregiving support. |

| Guyon- Harris et al. (2017) | 95 | Predominately low-income ethnic minority adults | Emotional abuse, physical abuse, or sexual abuse before age 17 and/or intimate partner psychological, physical, or sexual violence and victimization in the past year | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Conflict Tactics Scales-2 (CTS-2) |

Social support from family and friends | Prenatal (3rd trimester) & Postpartum (1 and 2 years) | Trajectory of PTSD symptoms (stable low PTSD symptoms vs. moderate dysfunction) | Among women with a history of childhood abuse and/or intimate partner violence, women with low PTSD symptoms across time reported consistently higher levels of family social support across time than the women with moderate PTSD symptoms over time. Levels of social support from friends did not differ between the two groups. |

| Leeners et al. (2016) | 255 | Predominately white adults | Sexual abuse before age 18 | Modified form of Wyatt Sexual History Questionnaire | Presence of trusted person at birth, participation in medical decision making | Delivery | Satisfaction with birth experience and fear during birth experience | Having a trusted person in the delivery room and participation in medical decision-making were associated with greater satisfaction with the delivery experience. |

| Leigh & Milgrom (2008) | 367 | Australian pregnant women | Emotional, sexual, & physical abuse during childhood | Extracted from Demographics & Psychosocial Risk Factors Questionnaire | Six domains of social support | Prenatal (26–34 weeks) & Postpartum (10–12 weeks) | Depressive symptoms | Higher social support was associated with fewer prenatal depressive symptoms. |

| Meltzer-Brody et al. (2013) | 187 | Predominately low-income, racial and ethnic-minority Pregnant adolescents | Adolescents’ reported history of neglect and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse | Trauma history interview | Four domains of social support, paternal involvement | Prenatal (2nd or 3rd trimester) & Postpartum (6 weeks) | Depressive symptoms | Higher social support was associated with fewer prenatal depressive symptoms. Increased social support and greater involvement from the baby’s father were also associated with fewer postnatal depressive symptoms. |

| Milan et al. (2004) | 203 | Predominately low-income, ethnic-minority adolescents | Adolescents’ reported history of physical abuse | Physical Assault domain of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) | Supportive romantic relationship during pregnancy | Postpartum (4 months) | Mother-infant relationship difficulty | Adolescents’ greater physical abuse history predicted more mother-infant relationship difficulties in the low partner support group, but not in the high partner support group. |

| Mitchell et al. (2018) | 84 | Approximately 50% low- income, African American perinatal women | Childhood SES; Childhood trauma (emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect) | Perceived childhood social class, maternal and Paternal educational attainment; 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) | Social support from family, friends, and significant others | Prenatal (12, 20, & 29 weeks) and Postpartum (8 weeks) | Telomere length | Three indicators of childhood SES, low perceived childhood social class, low maternal educational attainment, and low paternal educational attainment, each predicted shorter telomere length; whereas high social support from family predicted longer telomere length. (Family social support did not moderate the relation between childhood SES and telomere length, and no significant differences in telomere length were found for childhood trauma and social support from friends and significant others.) |

| Olhaberry et al. | 96 | Chilean, low- income pregnant women | Sexual and/or physical abuse before age 17 | Specific items in the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA-Q) | Number of people providing support & satisfaction | Prenatal (3–7 months) | Depressive symptoms | Satisfaction with social networks was associated with fewer prenatal depressive symptoms. |

| Osborne & Rhodes (2001) | 265 | Predominately low-income, African American adolescents | Adolescents’ reported history of sexual victimization | Sexual Experiences Survey | Social support satisfaction | Prenatal & Postpartum (≤3 months) | Depressive and anxiety symptoms | Greater social support was associated with fewer anxiety and depressive symptoms during conditions of low stress for sexually-victimized adolescents. By contrast, non-victimized adolescents benefited from social support at moderate and high levels of stress. |

| Racine et al. (2018b) | 1994 | Predominately White pregnant women | Exposure to childhood abuse (physical, sexual, emotional) and family dysfunction (e.g., parent mental illness, substance abuse, incarceration, domestic violence) | 11-item modification of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) |

Four domains of social support | Prenatal (<25 weeks) | Prenatal health risk (based on maternal medical conditions, pregnancy history, substance use) | Social support moderated the association between ACEs and prenatal health risk. Higher levels of ACEs were associated with elevated prenatal health risks for women with low social support, but not for women with high social support. |

| Seng et al. (2013) | 566 | Adult & adolescent mothers | Physical abuse, sexual abuse emotional abuse, and physical neglect before age 16 | Life Stressor Checklist, 5 childhood items | Several domains of quality of life | Postpartum (6 weeks) | Symptoms of depression alone or comorbid with PTSD, impaired bonding with infant | Higher quality of life in late pregnancy was associated with fewer postpartum depressive symptoms and less impairment in mother-infant bonding. |

Internal cognitive/psychological capacities.

Four studies identified cognitive or psychological capacities that facilitate resilient functioning among mothers with childhood abuse and neglect. Three of these studies evaluated maternal mental health outcomes (Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Sexton et al., 2015). For instance, maternal coping ability, measured using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (2003), moderated the relation between childhood abuse and neglect, and maternal postpartum depression and PTSD symptoms. Mothers with high coping ability had fewer depressive and PTSD symptoms, compared to mothers with low coping ability (Sexton et al., 2015). Relatedly, in another sample, higher self-esteem and self-efficacy were associated with fewer prenatal depressive symptoms (Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013). Similarly, adolescents’ positive attributions about the pregnancy were also associated with lower prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms (Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013). Lastly, reflective functioning regarding traumatic experiences was identified as a promotive factor in predicting higher rates of their infants’ organized attachment for mothers with a history of childhood abuse and neglect (Berthelot et al., 2015).

External early resources.

Three studies investigated the role of positive childhood experiences in ameliorating adverse prenatal mental health outcomes, which highlights the developmental principle of developmental psychopathology that early experiences have enduring effects on developmental trajectories. Narayan and colleagues (2018) measured benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs), operationalized as perceived safety and security, a positive and predictable quality of life, and interpersonal support during childhood. For mothers with high levels of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), those who also had high levels of BCEs had significantly lower PTSD symptoms and exposure to stressful life events during pregnancy compared to mothers with high levels of ACEs, but low levels of BCEs. Chung and colleagues (2008) similarly assessed positive influences in childhood, measured as positive parental relationships, and physical and verbal affection. They found a dose-response relationship between these positive childhood influences and lower prenatal depressive symptoms (Chung et al., 2008). Among women with a history of childhood sexual abuse, those who had a positive maternal relationship during childhood were less likely to have depressive symptoms compared to those who did not have a positive maternal relationship. Among women whose parent had gotten in trouble with the law, those who reported being hugged often during childhood were less likely to have depressive symptoms (Chung et al., 2008). Alternatively, a third study found that positive care in childhood did not significantly moderate the relation between history of childhood neglect, and maternal parenting empathy or neglect of her infant (Bartlett & Easterbrooks, 2015).

External contemporaneous resources.

Fourteen studies focused on external contemporaneous resources as protective or promotive factors. Social support was the most frequently studied external contemporaneous resource; only one study assessed additional external resources such as satisfaction with housing, school, work, and community (Seng et al., 2013). Of note, social support was defined in diverse ways across studies including social support frequency, perceived social support, and reported satisfaction with social support. Studies also assessed multiple domains of social support (e.g., emotional support, tangible support) and support received from different individuals, including romantic partners, family members, friends, and healthcare providers. The protective and/or promotive influence of social support is reported below as it relates to three outcomes: maternal mental health, maternal health/physiology, and mother-child relationships. Seng and colleagues’ (2013) study is discussed in regards to both the maternal mental health and mother-child relationship outcomes.

Six studies found that social support promoted positive maternal mental health outcomes. Higher perceived social support from family members and romantic partners (but not friends) significantly differentiated women with stable, low PTSD trajectories from those with moderate dysfunction PTSD trajectories across the pregnancy and postpartum periods (Guyon-Harris et al., 2017). Additionally, for pregnant and early postpartum adolescents with a history of sexual abuse, social support satisfaction was associated with fewer anxiety and depressive symptoms during conditions of low stress (Osborne & Rhodes, 2001). Studies assessing the influence of social support on depression outcomes found that the availability of support and perceived satisfaction with social support across multiple support domains was associated with fewer prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms (Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Olhaberry et al., 2014). Involvement of the infant’s father was also associated with lower postpartum depressive symptoms (Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013). Finally, higher life satisfaction, including satisfaction with support from partners, family, and friends; and from work, community, and housing, was associated with lower postpartum PTSD and comorbid depressive symptoms (Seng et al., 2013).

Five studies assessed effects of social support on maternal health (both biological health, and health care utilization) and physiology (Bell & Seng, 2013; Bublitz et al., 2014; Leeners et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2018; Racine et al., 2018b). Support from family moderated the association between childhood sexual abuse and cortisol awakening response (CAR) trajectories across pregnancy, and women who reported higher support displayed more typical CAR across pregnancy (Bublitz et al., 2014). Similarly, high social support from family, but not from friends and significant others, predicted longer perinatal telomere length (Mitchell et al., 2018).

Bell and Seng (2013) specifically examined support from health care providers; they found that women with histories of abuse and neglect were more likely to receive adequate prenatal care when they utilized mental health services prior to pregnancy and had a stronger alliance with medical providers during pregnancy. Additionally, the presence of a trusted person during delivery and participation in medical decision-making was associated with satisfaction with the birth experience for women exposed to childhood sexual abuse (Leeners et al., 2016). Lastly, social support moderated the association between ACEs and antepartum risk; for women with high ACEs and high social support, there was no association between ACEs and antepartum health risk or complications (Racine et al., 2018b).

Four studies described social support as supporting maternal-infant relationships among mothers with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. More frequent social support was associated with higher levels of maternal empathy towards her infant (Bartlett & Easterbrooks, 2015). Perceived support from romantic partners was also found to protect against adolescent mothers’ relationship difficulties with infants (Milan et al., 2004), such that physical abuse history predicted mother-infant relationship difficulties only for adolescents with low partner support (Milan et al., 2004). Notably, one study found that not relying on the family of origin for support was associated with mothers’ lower likelihood of perpetrating abuse and neglect of infants (Easterbrooks et al., 2011). Lastly, among a sample of adult and adolescent mothers, higher quality of life in late pregnancy (including satisfaction with relationships, work, school, and community) supported stronger bonding with infants (Seng et al., 2013).

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to identify promotive and protective factors associated with well-being during the perinatal period in women with childhood adversity to inform future prevention and intervention efforts that may interrupt the intergenerational transmission of risk from mothers to babies. Results represent studies of protective factors, which support adaptive functioning in individuals with elevated levels of risk, and promotive factors, which foster positive development across levels of risk, and this distinction is made below when possible. Utilizing a multilevel approach to understand resilience processes, the promotive and protective factors were organized into three groups: a) internal cognitive/psychological characteristics, b) external early resources, and c) external contemporaneous resources.

Internal Cognitive/Psychological Factors

Internal cognitive and psychological capacities were measured in a variety of ways across four studies (e.g., self-esteem, reflective functioning, and positive attributions about the pregnancy). Despite different measurements of internal cognitive/psychological factors, we see the emergence of parallel findings across diverse populations, including international and adolescent samples. For instance, three studies in this review found that internal cognitive/psychological factors were associated with fewer maternal depressive symptoms during the perinatal period (Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Sexton et al., 2015). These studies, although utilizing different constructs, all assessed aspects of one’s perceived ability to persist despite adversity. Thus, internal cognitive/psychological factors may be particularly important for decreasing perinatal depressive symptoms, especially given evidence that women perceive decreases in their cognitive and memory abilities during the perinatal period, which may negatively impact self-efficacy and self-esteem (Cuttler, Graf, Pawluski,, & Galea, 2011; Glynn et al., 2010). In addition, internal capacities may be especially crucial to strengthen in adolescent mothers, as the prevalence of perinatal depression is often higher in adolescent versus adult mothers (Hodgkinson, Beers, Southammakosane & Lewin, 2014). Together, these findings highlight the lifespan principle of developmental psychopathology, that development is continuous throughout the lifespan and involves adaptation and maladaptation during different developmental transitions, including the transition to parenthood.

Of note, most of these studies demonstrated the positive impact of internal capacities within their study sample but did not elucidate whether a particular internal/psychological factor has a stronger impact for high risk groups as compared to low risk groups. Sexton and colleagues (2015), however, identified and compared mothers with a range of childhood abuse and neglect experiences, and were thus able to establish a robust protective effect of resilience through moderation (i.e., better coping ability led to greater decreases in PTSD symptoms for individuals with high levels of childhood abuse and neglect).

External Early Childhood Resources

Three studies examined positive childhood experiences in concert with exposure to childhood adversity (Bartlett & Easterbrooks, 2015; Chung et al., 2008; Narayan et al., 2018). In defining positive childhood experiences, Chung and colleagues (2008) focused on positive childhood relationships, whereas Narayan and colleagues (2018) also identified the broader index of BCEs. Despite these differing definitions, both studies demonstrated that positive early childhood resources were associated with fewer symptoms of prenatal psychopathology, specifically PTSD and depression (Chung et al., 2008; Narayan et al., 2018). By contrast, Bartlett and Easterbrooks (2015) did not find a significant effect of positive care in childhood in moderating mother-child relationship outcomes, including parenting empathy or neglect of infants. It is possible that positive care in childhood is more effective at promoting maternal mental health, rather than parenting outcomes; however more research is needed on this distinction. Further, Bartlett and Easterbrooks (2015) utilized an adolescent sample, and it is possible that the protective/promotive function of early external childhood resources may differ between adolescent and adult mothers. Together, these studies suggest that understanding how positive childhood experiences within the context of childhood adversity support perinatal health is a promising area for future research, and in line with the developmental principle central to the developmental psychopathology perspective. Given the salience of maternal memories of childhood caregiving experiences during the perinatal period, the transition to parenthood maybe a particularly opportune time to harness positive childhood experiences as a protective/promotive factor (Slade et al., 2009; Glynn, 2010). Identifying which positive experiences are most important and whether they serve promotive or protective functions are also important next steps.

External Contemporaneous Resources

Social support was the most frequently studied protective or promotive factor. Social support was found to influence a variety of outcomes, including maternal mental health (e.g., depression); biological health (e.g., cortisol awakening response); and outcomes related to the maternal-child relationship (e.g., perpetration of child abuse and neglect), demonstrating the protective and promotive effect of social support across domains of resilience.

Four studies demonstrated a promotive or protective effect of social support on depression and/or PTSD symptoms during the perinatal period (Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Olhaberry et al., 2014; Osborne & Rhodes, 2001). These results are in line with the systems principle of developmental psychology, which posits that developmental trajectories arise from the complex interplay between an individual and various aspects of the environment. The studies included international samples and a sample of adolescent mothers, demonstrating the positive influence of social support across cultural and contextual bounds. It is especially important to understand the promotive and/or protective effect of social support on perinatal mental health outcomes, because changes in sex hormones, inflammation, and HPA axis activity may engender higher risk of perinatal psychopathology, particularly depression (Christian, Franco, Glaser, & Iams, 2009; Workman, Barha, & Galea, 2012). Notably most of, these studies captured promotive effects because they show a benefit of social support regardless of level of childhood risk. Future studies would benefit from comparing individuals with histories of childhood abuse and neglect to those without such histories (e.g., Osborne & Rhodes, 2001), in order to understand if social support functions differentially for high-risk populations, thus establishing a protective effect.

Although some studies measured social support using broad measures, multiple studies examined the promotive/protective effect of support from a particular type of relationship, such as one’s romantic partner, family, friends, or health care providers. The existing evidence suggests that, more than support from friends, support from family is associated with positive outcomes for mothers with histories of childhood abuse and neglect (Bublitz et al., 2014; Guyon-Harris et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2018). Additional evidence also suggests that support from romantic partners fosters positive perinatal outcomes including fewer mother-infant relationship problems and less maternal depression symptoms (Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Milan et al., 2004). Childhood abuse and neglect often occurs in the context of attachment relationships (Slade et al., 2009; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Safe and supportive attachment relationships in adulthood, including relations with family and with one’s romantic partner, may therefore be particularly important for combating and compensating against the negative effects of childhood abuse and neglect and promoting positive outcomes during the perinatal period (Guyon-Harris et al., 2017).

Our understanding of the impact of support from a specific type of relationship is complicated, however, by one study in our review which found that under conditions of high adversity, mothers were less likely to perpetrate child abuse and neglect against infants when they did not live with their family of origin and did not rely on their own mother for emotional or caregiving support (Easterbrooks et al., 2011). This finding highlights the complicated reality many individuals who experience childhood abuse and neglect face regarding relationships with their families of origin. Often, individuals with abuse histories must continue to rely on their perpetrator(s) for emotional and/or tangible support, which may lead to psychological conflict and distress (Freyd, 1996). This conflict may be particularly relevant for adolescent and young mothers, who were the focus of Easterbrook and colleagues’ study, as they may be more likely to need support from family to combat the financial, educational and psychological challenges associated with adolescent pregnancy (Hodgkinson et al., 2014). For women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect, social support from family may not be protective if it includes the perpetrator of the abuse. This finding underscores the multifinality principle of developmental psychopathology, in that similar experiences (e.g., support from family of origin) can lead to a variety of pathways, some characterized by positive outcomes and others by increased stress.

Finally, evidence from this review suggests that the context in which support is provided effects the extent to which support serves protective and/or promotive functions. For adolescent mothers with a history of childhood sexual abuse, social support was associated with decreased depression and anxiety symptoms only under conditions of low stress (Osborne & Rhodes, 2001). It may be that it is more difficult for women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect to seek out support during times of high stress compared to women without such histories. Additionally, if family relationships are complicated by the ongoing presence of the childhood abuse perpetrator, and women must seek out alternative sources of support, the support they receive may be lower quality or less reliable, making it less effective in times of high stress. Given the constraints of women’s social support in high-risk contexts, more research on the supportive role of health care service providers is essential (Bell & Seng, 2013). In future research on contemporaneous factors, it will be important to also widen our consideration of other external resources to include economic resources, academic and career satisfaction, neighborhood safety, and community support, so they can also be leveraged to promote well-being during the perinatal period and deter the intergenerational transmission of risk.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Strengths of this review include that it is the first of which we are aware to systematically synthesize the literature on promotive and protective factors that support perinatal psychological, health, and relationship outcomes in the context of maternal childhood adversity. Although the corpus of total reviewed studies is small, findings are drawn from samples reflecting a range of developmental stages (e.g., adolescents and adults), and ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. Despite these strengths, there are several limitations and directions for future research. First, due to limited number of studies and heterogenous study outcomes, the current review does not include a meta-analysis. A meta-analysis would be an important future direction once more research devoted to understanding positive influences that mitigate effects of childhood abuse and neglect on negative maternal and fetal outcomes is conducted. Additional limitations include that inter-rater reliability was not used at the data extraction phase and that this review solely focused on basic, rather than intervention and prevention research. Below, several key areas for future directions are provided.

Timing and longitudinal processes.

An important goal for future work is to increase understanding of how protective and promotive processes differentially influence outcomes over the prenatal and postpartum periods, and beyond. Given research evidence indicating increased levels of risk for psychopathology and stress during the perinatal period as a result of hormonal, biological and psychological changes, it is essential to elucidate whether positive influences function differently during this period as well (Christian et al., 2009; Workman et al., 2012). Most of the reviewed studies focused exclusively on a single time point during either the prenatal or postpartum periods, although a few studies incorporated measurement of outcomes at multiple perinatal time points. For example, some studies assessed both prenatal and postpartum outcomes (Guyon-Harris et al., 2017; Leigh & Milgrom, 2008; Mitchell et al., 2018; Meltzer-Brody et al. 2013; Osborne & Rhodes, 2001), helping to define the impact of protective and promotive factors throughout the perinatal period. Furthermore, some studies measured trajectories of maternal and child outcomes over time, such as trajectories of PTSD symptoms (Guyon-Harris et al., 2017) and trajectories of cortisol awakening responses (Bublitz et al., 2014), thus illuminating the importance of characterizing adaptive and nonadaptive development across the perinatal period. Following developmental psychopathology and contemporary resilience research, future studies should investigate benefits of protective and promotive factors over time to elucidate how dynamic resilience processes change during lifespan transitions such as pregnancy.

Measurement of promotive versus protective factors.

Many studies did not distinguish between whether they were analyzing a promotive or protective effect because they utilized samples that exclusively experienced childhood abuse and neglect without a control group. While elucidating factors that have positive main effects for mothers who have experienced childhood abuse and neglect is promising, and likely suggests a protective effect, examining the same associations in a low-risk comparison sample would allow researchers to demonstrate that a particular factor has a greater positive influence in high risk as opposed to low risk contexts, thus establishing a more robust protective effect. It is also important that future research identify mechanisms through which promotive influences (i.e., supporting adaptive outcomes across all levels of risk) and protective influences (i.e., supporting adaptive development among individuals at high risk) operate to understand not just what factors support healthy perinatal outcomes, but for whom and through which mechanisms (Masten, 2014; Narayan, 2015).

Interdependent and transactional processes.

The majority of studies assessed a single promotive/protective factor, rather than adopting a multilevel approach. Although protective and promotive factors were categorized into three main areas within this review, we do not wish to suggest that investigation of these factors should be separate. Resilience research encourages the investigation of interactive effects of protective/promotive factors at multiple levels from genetic and neural to cultural and societal systems, which is aligned with the multilevel principle of developmental psychopathology and current resilience research priorities (Masten, 2014).

Conclusions.

Overall, the current review demonstrates that to better understand perinatal promotive and protective processes for women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect, future studies must conceptualize resilience as a dynamic process that can be measured at multiple ecological levels. Although it will be essential to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which multiple protective and promotive factors support maternal and fetal wellbeing, findings from this review suggest that perinatal screening, prevention, and intervention efforts can transform mental and physical health trajectories for both mother and child. Future research and review efforts should investigate the efficacy of prevention and intervention (e.g., psychotherapy, medication use) for supporting perinatal health and deterring the intergenerational transmission of risk (Davis, Hankin, , & Hoffman, 2018). Future work in this area could include bolstering women’s internal capacities, such as self-efficacy and coping skills; helping women to draw on memories of positive childhood experiences with caregivers; and strengthening women’s social support networks. Such strategies may measurably improve maternal mental health and physiology, and support maternal-infant bonding and attachment. In this way, promotive and protective factors can be harnessed to curb the intergenerational transmission of risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments and Author Contact

This project was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; RO1 MH109662 and P50 MH096889) to E. Poggi Davis and L. Grande, from the University of Denver Inclusive Engagement (IE) Fellowship to V. Atzl and L. Grande, and from the University of Denver Pubic Impact Fellowship to A. Narayan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Afifi TO, & MacMillan HL (2011). Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 266–272. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA (2004). Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcomes, and medical utilization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65, 10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, & Easterbrooks MA (2015). The moderating effect of relationships on intergenerational risk for infant neglect by young mothers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 45, 21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SA, & Seng J (2013). Childhood maltreatment history, posttraumatic relational sequelae, and prenatal care utilization. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 42, 404–415. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot N, Ensink K, Bernazzani O, Normandin L, Luyten P, & Fonagy P (2015). Intergenerational transmission of attachment in abused and neglected mothers: The role of trauma-specific reflective functioning. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36, 200–212. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz MH, Parade S, & Stroud LR (2014). The effects of childhood sexual abuse on cortisol trajectories in pregnancy are moderated by current family functioning. Biological Psychology, 103, 152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, Toepfer P, Fair DA, Simhan HN, Heim CM & Wadhwa PD (2017). Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: implications for fetal brain development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, & Sikkema KJ (2016). Childhood maltreatment and perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: a systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17, 427–453. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Franco A, Glaser R, & Iams JD (2009). Depressive symptoms are associated with elevated serum proinflammatory cytokines among pregnant women. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23, 750–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Mathew L, Elo IT, Coyne JC, & Culhane JF (2008). Depressive symptoms in disadvantaged women receiving prenatal care: the influence of adverse and positive childhood experiences. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 8, 109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D (2013). Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children–past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 402–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Rogosch FA (1996). Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, & Davidson JR (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor‐ Davidson resilience scale (CD‐ RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttler C, Graf P, Pawluski JL, & Galea LA (2011). Everyday life memory deficits in pregnant women. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65, 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E, Hankin B, Swales D, & Hoffman M (2018). An experimental test of the fetal programming hypothesis: Can we reduce child ontogenetic vulnerability to psychopathology by decreasing maternal depression? Development and Psychopathology, 30(3), 787–806. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418000470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domhardt M, Münzer A, Fegert JM, & Goldbeck L (2015). Resilience in survivors of child sexual abuse: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16, 476–493. doi: 10.1177/1524838014557288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuMont KA, Widom CS, & Czaja SJ (2007). Predictors of resilience in abused and neglected children grown-up: The role of individual and neighborhood characteristics. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 255–274. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Chaudhuri JH, Bartlett JD, & Copeman A (2011). Resilience in parenting among young mothers: Family and ecological risks and opportunities. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LM (2010). Giving birth to a new brain: hormone exposures of pregnancy influence human memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35, 1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graignic-Philippe R, Dayan J, Chokron S, Jacquet AY, & Tordjman S (2014). Effects of prenatal stress on fetal and child development: a critical literature review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 43, 137–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon-Harris KL, Ahlfs-Dunn S, & Huth-Bocks A (2017). PTSD symptom trajectories among mothers reporting interpersonal trauma: protective factors and parenting outcomes. Journal of Family Violence, 32, 657–667. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson S, Beers L, Southammakosane C, & Lewin A (2014). Addressing the mental health needs of pregnant and parenting adolescents. Pediatrics, 133, 114–122. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston D, Tough S, & Whitfield H (2012). Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 43, 683–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeners B, Görres G, Block E, & Hengartner MP (2016). Birth experiences in adult women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 83, 27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B, & Milgrom J (2008). Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 24. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, & Block D (1996). The disturbed caregiving system: Relations among childhood trauma, maternal caregiving, and infant affect and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 17, 257–275. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York:Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- McGloin JM, & Widom CS (2001). Resilience among abused and neglected children grown up. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 1021–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, Bledsoe-Mansori SE, Johnson N, Killian C, Hamer RM, Jackson C, Wessel J & Thorp J (2013). A prospective study of perinatal depression and trauma history in pregnant minority adolescents. American journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 208, 211–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Lewis J, Ethier K, Kershaw T, & Ickovics JR (2004). The impact of physical maltreatment history on the adolescent mother–infant relationship: Mediating and moderating effects during the transition to early parenthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AM, Kowalsky JM, Epel ES, Lin J, & Christian LM (2018). Childhood adversity, social support, and telomere length among perinatal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 87, 43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & PRISMA Group . (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan AJ (2015). Personal, dyadic, and contextual resilience in parents experiencing homelessness. Clinical Psychology Review, 36, 56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan AJ, Rivera LM, Bernstein RE, Castro G, Gantt T, Thomas M, Nau M, Harris WW, & Lieberman AF (2017). Between pregnancy and motherhood: Identifying unmet mental health needs in pregnant women with lifetime adversity. Zero to Three Journal, 37, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan AJ, Rivera LM, Bernstein RE, Harris WW, & Lieberman AF (2018). Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: a pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse & Neglect. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, & Vos T (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 9, e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olhaberry M, Zapata J, Escobar M, Mena C, Farkas C, Santelices MP, & Krause M (2014). Antenatal depression and its relationship with problem-solving strategies, childhood abuse, social support, and attachment styles in a low-income Chilean sample. Mental Health & Prevention, 2, 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne LN, & Rhodes JE (2001). The role of life stress and social support in the adjustment of sexually victimized pregnant and parenting minority adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 833–849. doi: 10.1023/A:1012911431047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine NM, Madigan SL, Plamondon AR, McDonald SW, & Tough SC (2018a). Differential associations of adverse childhood experience on maternal health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54, 368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine N, Madigan S, Plamondon A, Hetherington E, McDonald S, & Tough S (2018b). Maternal adverse childhood experiences and antepartum risks: the moderating role of social support. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0826-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabina C, & Banyard V (2015). Moving toward well-being: The role of protective factors in violence research. Psychology of Violence, 5, 337. doi: 10.1037/a0039686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandman CA, Davis EP, Buss C, & Glynn LM (2012). Exposure to prenatal psychobiological stress exerts programming influences on the mother and her fetus. Neuroendocrinology, 95, 8–21. doi: 10.1159/000327017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS (2002). A conceptual framework for research on lifetime violence, posttraumatic stress, and childbearing. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 47, 337–346. doi: 10.1016/S1526-9523(02)00275-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Sperlich M, Low LK, Ronis DL, Muzik M, & Liberzon I (2013). Childhood abuse history, posttraumatic stress disorder, postpartum mental health, and bonding: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 58, 57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00237.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton MB, Hamilton L, McGinnis EW, Rosenblum KL, & Muzik M (2015). The roles of resilience and childhood trauma history: main and moderating effects on postpartum maternal mental health and functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders, 174, 562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Cohen LJ, Sadler LS, & Miller M (2009). The psychology and psychopathology of pregnancy. Handbook of Infant Mental Health, 3, 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, & Carnes M (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 517–530. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, & Rutter M (1984). The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 17–29. doi: 10.2307/1129832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, & Samson JA (2013). Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: A case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 1114–1133. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman JL, Barha CK, & Galea LA (2012). Endocrine substrates of cognitive and affective changes during pregnancy and postpartum. Behavioral Neuroscience, 126, 54. doi: 10.1037/a0025538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.