Abstract

To identify modifications to amino acids directly induced by ionizing radiation (IR), free amino acids and 3-residue peptides were exposed to radiation generated by a linear accelerator (Linac) used in radiotherapy. Mass spectrometry was performed to detail the relative sensitivity to radiation as well as identify covalent, IR-dependent adducts. The order of reactivity of the 20 common amino acids was generally in agreement with published literature except for His (most reactive of the 20) and Cys (less reactive). Novel and previously identified modifications on the free amino acids were detected. Amino acids were far less reactive when flanked by glycine residues in a tripeptide. Order of reactivity, with GVG most and GEG least, was substantially altered, as were patterns of modification. IR reactivity of amino acids is clearly and strongly affected by conversion of the α-amino and α-carboxyl groups to peptide bonds, and the presence of neighboring amino acid residues.

Biological systems have evolved multiple mechanisms to combat oxidative damage induced by free radicals (1-8). Acute exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) produces higher levels of reactive oxygen species than most organisms can ameliorate, though tolerance varies significantly between organisms. For example, a dose of <10 Gray (Gy) is lethal to Homo sapiens (9), whereas the radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans can survive doses in excess of 10,000 Gy (2). All cellular macromolecules are targets of IR-generated free radicals. The in vivo effect on the genome and transcriptome (e.g., DNA or RNA strand breakage) is substantial (10). However, the proteome may be the primary target of free radicals due to protein abundance and reactivity (11, 12).

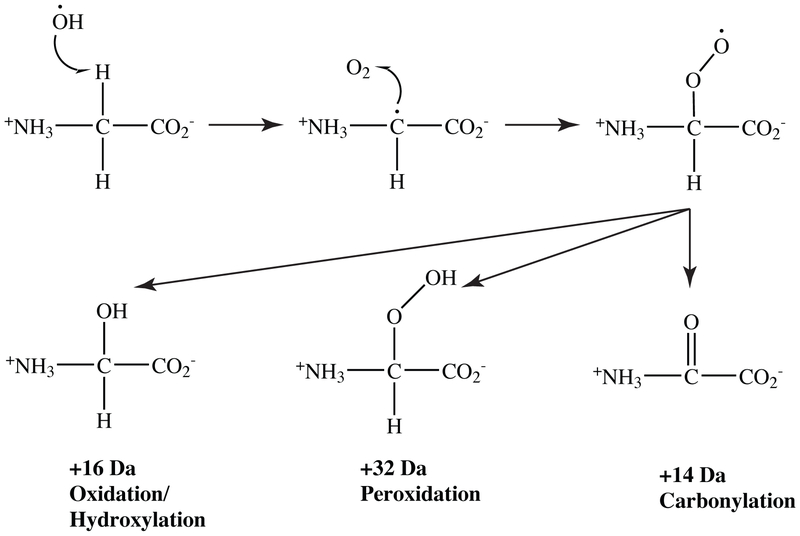

In aqueous systems, IR treatment produces many reactive species, including solvated free electrons (eaq−), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), superoxides (O2−), hydroperoxyls (HO2•), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The effects of these species on free amino acids in solution have been studied using synchrotron-generated x-ray radiation or elemental decay-generated γ-rays (13-17). Major products of irradiation involve classical oxidation, such as +16 (oxidation/hydroxylation; ─CH2─→ ─CH─OH) and +14 (carbonylation; ─CH2─ → C=0)(13-15). Other products have been noted as well, such as side chain ring opening or isobaric conversion between amino acids via loss of side chain groups (17). In addition, rate constants have been established for the reaction of eaq− and OH• with amino acids (18, 19). Relative reactivities of common amino acids, encompassing many possible products, have also been empirically determined by monitoring the loss of the unmodified amino acid reactant using mass spectrometry (17, 20).

The effects of IR on particular amino acids have been examined within a peptide context as well. In general, the peptides used have contained sequences of biological interest or have focused on specific chemistries (16, 17, 21-24). In a 2012 study by Morgan, et al., peptides containing Gly/Ala/Val/Pro residues were used to examine a reported preference for these residues in radical-dependent peptide cleavage (24). A 2009 study by Saludino et al. examined the effect of aliphatic side group radicals within a tripeptide context as a source of proximal oxidation (23). The Chance group has broadly defined acidic, basic, and sulfur-containing side chain chemistries upon IR irradiation in a variety of peptide contexts (16, 21, 22). To build on and expand this base, we now provide a comprehensive comparison of relative sensitivity to radiation and modifications between all 20 of the common amino acids free in solution or within a standardized tripeptide context.

The effect of IR on amino acid chemistry is highly relevant to fields ranging from cancer radiotherapy to space travel to national defense (25-29). The first step in detailing these chemistries is to bridge the gaps in our understanding of the differences between IR effects on free amino acids and amino acids participating in peptide bonds. Towards that end, we have used mass spectrometry to empirically analyze relative sensitivity to radiation and modifications induced by IR for both free amino acids and amino acids in tripeptides. The work makes use of a Linac, a clinical linear accelerator commonly used in tumor radiotherapy. The Linac-produced electron beam is maintained by the University of Wisconsin (UW)-Madison Medical Radiation Research Center, which provides a highly controlled and reproducible source of IR for building a strong foundational understanding of IR-induced amino acid modification (30).

Overview of experimental design and rationale

Free amino acids in solution were first analyzed via mass spectrometry following a range of IR doses from the Linac. Relative sensitivity to radiation and dose-dependent product formation were documented. Next, tripeptides were synthesized with the composition G-X-G, where every amino acid was separately placed in the X position. Glycine was chosen as it is relatively unreactive compared to the remaining 19 amino acids free in solution. With the amino acids thus placed in a more protein-relevant context, we both determined IR sensitivity and identified covalent modifications on the tripeptides using mass spectrometry. This work aims to catalog the modifications induced by UW-Madison’s IR source for this and future studies and provide a benchmark comparison with other previously-reported reactivities of amino acids with IR-generated radicals.

IR response and modification of free amino acids in aqueous solution

To begin with the simplest possible system, 50 μM solutions were made of each of the common 20 amino acids in water. Each solution was exposed to 0, 100, 200, 500 or 1000 Gy of IR. The products were analyzed using electrospray ionization-time of flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectrometry with both positive and negative mode (Table S1), and the loss of the unmodified form of the amino acids was monitored. This is shown here as a percentage of the control signal per amino acid remaining following each IR dose (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A, Raw signal loss for unmodified amino acids at 50 μM in H2O. B, Linearization from 0Gy to 200Gy dosage, the linear range of reactant loss. C, Relative reactivities of amino acids charted altogether and compared to reactivities determined using previous techniques17,20,31. D, The cluster of aromatic ring-containing residues. E, Modification events identified and their abundance on Tyr, from ESI-TOF MS.

For the majority of amino acids, a significant portion of signal from the unmodified forms was lost after the 200 Gy dose, suggesting their complete conversion to products at or before the subsequent 500 Gy dose (Fig. 1A). For the majority of amino acids with unmodified signal remaining after 200 Gy, the linear rate of loss displayed from 0 to 200 Gy then slowed significantly for higher doses. Concurrent with this, increased production of many modifications was lost following the 200 Gy dose (Figs. S1-S3). Furthermore, in the cases where modification signals still increased beyond the 200 Gy dose, the rate was significantly slower (Figs. S1-S3). Thus, linear relative rates of dose response, corresponding to their respective IR sensitivities, were built using the data from 0 to 200 Gy for each amino acid, and plotted over this range (Fig. 1B, based on data from Table S1). Using these relative sensitivities, a scale of response was constructed and compared to published data from other ROS-producing techniques (17, 18, 31) (Fig. 1C). The most sensitive amino acid was His. Relative to previous studies (16, 17, 31), the significant response of His observed here is unusual and may be specific to the high energy electron beam used. Otherwise, the relative amino acid dose responses are generally consistent with previously reported data (17).

Correlations of sensitivity with side group chemistries and physicochemical properties of amino acids, including volume(32), hydropathy(33), and pKa/pI values, were calculated (Figs. S4, S5). The response of the amino acids containing aromatic R groups produced the most notable grouping (Fig. 1D). The strongest correlation of IR sensitivity level with a physicochemical property was with molecular volume (R2 = 0.5672, Fig S5), suggesting there may be some dependence on volume for the relative sensitivities to radiation we observe. The aromatic ring containing residues were all highly responsive, and exhibited similar dose responses of modification (Fig. 1D). They also all exhibited multiple oxidation events (Figs. 1E, S6), which we hypothesize is due to resonance associated with the aromatic rings. No other significant correlations between responses or modifications and chemical properties of amino acids were observed (Figs. S4, S5).

Classical hydroxylation (+16)(+O) was observed on each amino acid but Asp, Cys, and Gly (Table 1). Dihydroxylation/peroxidation (+32)(+2O) events were seen on the vast majority of amino acids. Carbonylation (+14) was observed on less than half of the amino acids. For His, Lys, and Cys only, adducts of +48 were observed (Tables 1, S1). This is likely a combination of +16 hydroxyl and +32 dihydroxyl/peroxy product mass shifts. A generalized reaction scheme for these common oxidative modifications is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Linac IR-induced products of free amino acids. Shown in columns are presence (+) of common modifications, including oxidation/hydroxylation (+16Da), peroxidation (+32Da), multiple oxidation events (+16(n)Da, where n is the number of events observed), and carbonylation (+14Da). Uncommon modifications are displayed in the “Misc.” column, and the mass shifts, in Da, are shown for each amino acid.

| Modifications | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid | R chemistry | +16Da/ +(O) |

+32Da/+ 2(O) |

+16(n) Da/ +n (O) |

+14Da/ +(=O) |

Misc. |

| F | aromatic | + | + | +(3-5) | +66, +82 | |

| W | aromatic | + | + | +(3-6) | +50, +66, +82 | |

| Y | aromatic | + | + | +(3-4) | +66 | |

| D | acidic | −30, +137 | ||||

| E | acidic | + | + | + | −30, −14 | |

| A | nonpolar | + | + | |||

| G | nonpolar | |||||

| I | nonpolar | + | + | + | ||

| L | nonpolar | + | + | + | ||

| M | nonpolar | + | −55 | |||

| P | nonpolar | + | + | + | ||

| V | nonpolar | + | + | + | ||

| C | polar | +(3) | ||||

| N | polar | + | + | |||

| Q | polar | + | + | + | ||

| S | polar | + | −2, −28 | |||

| T | polar | + | + | −46 | ||

| H | basic | + | + | +(3) | +5, +8, +35, −10, −22, −28 | |

| K | basic | + | + | +(3) | + | |

| R | basic | + | + | + | −43, −61 | |

Figure 2.

Generalized reaction scheme for the most common oxidative modifications to amino acids and proteins. Following hydrogen abstraction at the α-carbon, carbon or oxygen radical species can further react to produce hydroxylation (+16), peroxidation (+32), or carbonylation (+14).

With IR treatment, a number of products of very low signal with less mass than the unmodified amino acid were observed for the majority of amino acids (Table S1). Despite the abundance of many products, including classical oxidation and others with known atomic composition, there was not a strong correlation between the disappearance of unmodified amino acid variants (orders of magnitude) and the appearance of particular products. Thus, the reaction pathways leading to products caused by IR are likely to be complex, an issue that future work must address.

Modifications of aromatic amino acids in solution

The aromatic ring-containing residues were the most highly modified subset of amino acids. Each was significantly modified with +16n adducts, up to n=6 (Tables 1,S1). For Trp and Phe, higher oxidation states were observed with a 32+2 (+34) mass shift, which may be a result of a combination of di-hydroxylation of the benzene ring across a double bond (+17 each). These occurred in addition to hydroxylation elsewhere in the molecule (+16). The major products of Trp oxidation are hydroxytryptophan (+16), di-hydroxytryptophan (+32), kynurenine (+4), and oxidation or N-formylation of the kynurenine product (+20 or +32, respectively) (15, 17, 34). Tyr conversion to dihydroxy derivatives and subsequent dimerization was observed in previous work (35-37), though this product was not observed here. Finally, Phe hydroxylation about the benzene ring to form ortho- or meta-tyrosine has been observed previously (15, 38). However, the multiple oxidation events on all aromatic residues described above have not been previously reported (Fig. S6). A combination of hydroxylation (+16) and peroxidation (+32) events may explain the results of Fig. S6, though the extent of either cannot be determined for the higher order modifications. We hypothesize that the reactivity patterns of aromatic amino acids observed reflect the use of free amino acids in the current study, leading to some novel patterns not observed in the peptides used in the previous studies cited. Furthermore, the loci of modifications were not identified, so it is possible that hydroxylation and peroxidation are occurring throughout the molecules, rather than solely on the benzene rings.

Modifications of acidic amino acids in solution

Consistent with previous observations (15, 22), decarboxylation of the R-group was seen on the negatively charged amino acids Asp and Glu (Tables 1, S1). On Glu, hydroxylation (+16), peroxidation (+32), and carbonylation (+14) were all seen. A–14 mass shift (described previously (16) as oxidative decarboxylation followed by a +16 oxidative addition) was also observed, whereas no shift was seen on Asp. However, a significant mass shift of +137 was seen on Asp, which is 5 Da heavier than a dimerized form of Asp. At this point, it cannot be determined whether or not this truly is a dimerized Asp product. This mass at ca. 271 m/z was present at low signal in the untreated samples, though its formation is clearly induced to some degree by IR treatment. Thus, it may be a change induced to different levels by both ambient IR and aging of the powdered stock in an aerobic environment.

Modifications of aliphatic/nonpolar amino acids in solution

IR treatment of hydrocarbon aliphatic/nonpolar amino acids yielded hydroxylation (+16), dihydroxylation/peroxidation (+32), and carbonylation (+14), in line with the literature (Tables 1, S1)(14, 15, 17). Gly exhibited the lowest dose response, as observed previously (17, 19). Given that only a 4-fold loss of Gly was observed with the strongest IR treatment and no discrete product formation was observed, we hypothesize that formation of many different products below the limit of detection may be occurring. Furthermore, much of the literature suggests the major product of Gly modification with radicals occurs as backbone cleavage of polypeptides (19, 39, 40), which would not be observed in these data. Relative to Gly and Ala, more modification is seen on the nonpolar residues with a greater number of C-H bonds(Ile, Leu, and Val) as previously noted (11). Other minor products of the hydrocarbon aliphatic acids have been observed under a variety of conditions, but none were found here (31). Modification of +16, +32, and +14 was seen on Pro. The +16 mass shift on Pro could represent either 5-hydroxyproline or glutamyl semialdehyde, as the two species are reportedly in equilibrium (40-43). Similarly, a mass shift of +32 corresponds to either dihydroxylation, peroxidation, or conversion to Glu. The +14 product is conversion to pyroglutamic acid via carbonylation(15, 17).

Modifications of polar amino acids in solution

Amino acids containing polar side chains yielded a wider variety of products than those in the nonpolar group (Tables 1, S1). Asn, Gln, Ser, and Thr have not been as extensively studied as the other amino acids. Hydroxylation and carbonylation have been reported for Asn and Gln, though product formation is low in signal (16). In addition to hydroxylation on both Asn and Gln, we observed dihydroxylation/peroxidation (+32), the first report of such, as well as carbonylation (+14) on Gln. No other Asn or Gln products were observed. Both Ser and Thr were hydroxylated (+16), whereas irradiation of Thr also yielded a dihydroxylation/peroxidation (+32) product. Consistent with previously published data, a mass shift of −2 was observed on Ser, corresponding to hydroxyl side chain conversion to a carbonyl group (16). The strongest signals were mass shifts of −28 for Ser and −46 for Thr, corresponding to the loss of CO and C2OH6, respectively. We hypothesize that these alterations correspond to loss of the respective side chains, via an unknown mechanism.

Modifications of sulfur-containing amino acids in solution

In contrast to previous reports (16, 17, 31), the sulfur side chain-containing amino acids Met and Cys were not observed to be the most responsive. Whereas Met was one of the more sensitive residues, Cys was close to the middle of all of the amino acids with respect to sensitivity (Fig 1C). We identified a mass shift of + 16 on Met to form methionine sulfoxide, corresponding to the classical oxidative product previously reported many times (16, 17, 31, 44, 45). Sulfoxide formation is strongly induced at a dose of 100 Gy, after which the signal remains stable at 200 Gy but drops significantly thereafter. In negative mode, a strong, dose-dependent signal that persisted to 1000 Gy was observed for methanesulfonic acid (−55, Table S1). Given the highly oxidative environment created upon irradiation, we posit this is a cleavage product of unmodified Met and methionine sulfoxide. We hypothesize that IR triggers a quick conversion of Met to methionine sulfoxide, after which the main byproduct is methanesulfonic acid.

Cys was less sensitive then previously reported (17, 31) (Fig. 1A). With Cys, the major product formed is cysteine sulfonic acid, the triply oxidized Cys species (+48). This modification has been observed on the tripeptide GCG and a much longer peptide (16) as well as free Cys (46, 47). Additionally, we observed formation of Cystine (Cys*), the disulfide-linked, dimeric form of Cys (Tables 1, S1). The proposed mechanism for Cys* formation is hydrogen abstraction from the sulfhydryl group followed by subsequent radical dimerization (31, 46, 47). The abundance of Cys* initially increases at 100 Gy and decreases at higher doses, presumably as other products are formed. Xu and Chance noted this phenomenon previously in experiments to irradiate a disulfide linked dipeptide (GC)2. They observed free dipeptide produced via disulfide cleavage(16). The major product was monomeric GC-sulfonic acid, as observed here. A number of additional products, including +16 and +32, were produced from the dipeptide as reported but not observed here with the free amino acid.

Modifications of basic amino acids in solution

Finally, the basic amino acids were all among the most sensitive (Fig. 1C). Their modification profiles also follow this trend. Mass adducts up to +48 were observed on both Lys and His. Arg produced unique products, and many products of His were seen (Tables 1, S1). Conversion of Arg to glutamic-semialdehyde (–43) has been noted multiple times, both in radiolysis and metal-catalyzed oxidation (21, 41, 43), and was also observed here. We also identified a −61 product of Arg, the molecular composition of which is unknown. On His, mass shifts of +5, +8, +35, −10, −22, and −28 were observed, in addition to mass shifts of +16n up to n=3. Oxidation to form 2-oxohistidine and the −22 conversion to Asp were noted many years ago (48), and the +5 and −10 products have been reported more recently (17, 21). Mass shifts within this dataset of +8, +35, and −28 are also present (Table SI). While studies have been published examining oxidation pathways of His (49-52), none of the reported intermediates are consistent with the masses of unknown composition identified here.

IR response of amino acids in a peptide context

A second goal of this study was to examine the effect of IR treatment on amino acids when the α-amino and α-carboxyl groups are incorporated into peptide bonds. Thus, we next turned to tripeptides. Gly, the least reactive residue, was chosen to provide the peptide linkages. This allowed us to isolate, as much as possible, the effects of the peptide bonds themselves. All 20 tripeptides were synthesized as G-X-G, where X is an amino acid. For 15 of the 20 tripeptides, a dose treatment from 100 to 1000 Gy was carried out, identical to the procedure used for the free amino acids, in water at a concentration of 50μM. Both technical (analyzing the same IR-treated sample multiple times on a mass spectrometer) and experimental (reperforming IR treatment with the same stocks and re-analyzing IR response) variability were assayed and the irradiation results were reproducible (Fig. S6). The tripeptide GWG was not soluble in water, but was solubilized into DMSO which was diluted to 0.8% for irradiation (Figure S7). GWG is not included in the chart of rates. Finally, at a presumed concentration of 50μM, the tripeptides GPG, GKG, GQG, and GDG, were significantly more sensitive than any of the other tripeptides and the appearance of their modifications followed curves resembling free amino acids, rather than the other tripeptides (data not shown). We reasoned that this was due to misreporting of their initial quantities, and repeated the treatment at different concentrations to determine which most accurately reflected the responses of the other tripeptides (Table S2). Thus, these 4 tripeptides were treated with IR at a 10-fold higher concentration than the others, in order to obtain both dose response and product formation curves representative of tripeptides (Table S3, Figs. S8-S10). With this caveat in mind, the rates for these four tripeptides are included alongside the other 15. However, we were able to accurately determine dose-dependent product formation for all 20 tripeptides. All of the tripeptides were subject to ESI-Orbitrap analysis in positive mode, with MS/MS fragmentation used as secondary confirmation for mass shifts (Table S3, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Example MS/MS spectra from unmodified tripeptide GCG and triply oxidized version demonstrating fragment ion identification and localization of oxidation to middle C residue. A, B, and Y refer to classic fragment ion products generated by collisionally-induced dissociation within the mass spectrometer.

Tripeptide response to irradiation was considerably different from that observed with the free amino acids. After 1000 Gy of treatment, unmodified signal remained for all of the tripeptides (Fig. 2A), indicating that they are far less sensitive to IR than free amino acids (Fig. 1A). Reactant loss was dose-dependent throughout the range of exposures (Fig. 3A), as was product formation (Figs. S8-S10). Thus, linear fitting to determine relative responses was performed using data across the full range of IR doses (Fig. 3B). GVG was the most IR sensitive tripeptide, whereas GKG was among the least, inverting the relative responses seen with the free amino acids. GAG and GGG were more sensitive than GYG and GFG, again in contrast to their behavior as free amino acids. Some tripeptides behaved similarly to their amino acid counterparts. GMG, GHG, and their free amino acid counterparts were among the most responsive species within their respective datasets. Similarly, the relative sensitivities of GTG and Thr were both in the middle of the order in both datasets.

Figure 3.

Raw signal loss for tripeptides at 50 μM in H2O. B, Linearization from 0Gy to 1000Gy dosage, the linear range of reactant loss. C, Comparison of relative reactivity rates of free amino acids and tripeptides. D, Reaction scheme for C-terminal decarboxylation. R represents the first and second residues, and the sidechain and C-terminus of the third Gly residues are shown in full.

The lower sensitivity of the tripeptides as compared to the free amino acids contradicts the idea that a larger volume may lead to higher reactivity, a correlation observed with free amino acids (Fig. S5). Indeed, measuring similar correlations between molecular weight or volume (53) and reactivity for the tripeptides yielded nothing significant (R2 = 0.0788 and 0.0803, respectively, Fig. S11). The lower and tighter spread of response rates obtained for the tripeptides as compared to the amino acids is also a notable result (Fig. 3B). Generally, IR-mediated radical modification of free amino acids first involves hydrogen abstraction from or radical attack of the α-carbon (Fig. 2) (13, 14, 17, 31, 40). The sensitivity of a given residue in a tripeptide may thus be reduced due to steric hindrance surrounding the α-carbon by the adjacent Gly residues. Converting the α-amino and α-carboxyl groups in a free amino acid to amides may also influence the overall reaction. Following the initial hydrogen abstraction, a tripeptide may have better resonance delocalization of the carbon radical intermediate than the free amino acid, leading to a longer-lived, more stable intermediate at this stage. The attachment of two Gly residues to the middle residue may explain the tighter spread of rates observed as well. Experiments with a range of tripeptide compositions and chemistries will address these as of yet unexplored phenomena in the future.

Similar to the discrepancy between the IR sensitivities observed for free amino acids and amino acids in tripeptides, patterns of modification were also different. By far, the most common product was decarboxylation (−30) of the C-terminus (Fig. 3D), which has been noted before in radiolytic modification studies with peptides of varying lengths and chemistries (16, 21, 22). Hydroxylation (+16) was observed on a subset of the tripeptides with aromatic and nonpolar side chain chemistries, a clear cluster of products. Carbonylation (+14) occurred mainly on the tripeptides with nonpolar side chains (Tables 2, S3). Peroxidation (+32) was also observed on a small subset of tripeptides. Previously, +32 mass shifts were observed only on short peptides containing Val, Gly, Ala, and Pro (24). Further, no peroxidation was observed on basic residues within longer peptides in a second study (21). We hypothesize that the differences between tripeptides and longer or more complex peptides can be attributed to a larger variety of chemistries, in addition to variables associated with buffer, IR source, and treatment conditions.

Table 2.

Linac IR-induced products of tripeptides. Shown in columns are presence (+) of modifications, including oxidation/hydroxylation (+16Da), peroxidation (+32Da), triple oxidation (+48Da), carbonylation (+14Da), and decarboxylation (−30Da). Uncommon modifications are displayed in the “Misc.” column, and the mass shifts, in Da, are shown for each amino acid. Dimerization of CGC is noted here as well.

| Modifications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tripeptide | R chemistry | +16Da/ +(O) |

+32Da/ +2(O) |

+48Da/ +3(O) |

+14Da/ +(=O) |

−30Da/ Decarb. |

Misc. |

| GFG | aromatic | + | + | ||||

| GWG | aromatic | + | + | + | +62, +82 | ||

| GYG | aromatic | + | + | ||||

| GDG | acidic | + | + | −32 | |||

| GEG | acidic | + | −105 | ||||

| GAG | nonpolar | + | −105 | ||||

| GGG | nonpolar | + | + | + | |||

| GIG | nonpolar | + | + | + | −4 | ||

| GLG | nonpolar | + | + | + | −4 | ||

| GMG | nonpolar | + | −14, −32, −50 | ||||

| GPG | nonpolar | + | + | + | + | −87, −104 | |

| GVG | nonpolar | + | + | + | −4 | ||

| GCG | polar | + | dimer | ||||

| GNG | polar | + | −48, −105 | ||||

| GQG | polar | + | + | + | −105 | ||

| GSG | polar | + | −2, −16 | ||||

| GTG | polar | + | −2, −48 | ||||

| GHG | basic | + | + | + | |||

| GKG | basic | + | + | + | + | ||

| GRG | basic | + | + | ||||

A precise mass shift of −105.042 was identified on GEG, GAG, GNG, and GQG (Table S3). Using exact mass calculations, this most likely reflects a loss of C3H7NO3 (54). The best described phenomenon with a comparable mass change is a radical reaction beginning at the α-carbon of the middle residue, (13, 14, 17, 31, 40), followed by subsequent cleavage of the C-terminal Gly residue and further decarboxylation. However, this leaves a loss of 2 hydrogen atoms unaccounted for. A similar mass shift (−104.056) was seen on GPG, which we hypothesize is a related product (Table S3), but small mass discrepancies indicate that more work is required to confirm or update this reaction assignment.

Modifications to polar and nonpolar residues in tripeptides

Consistent with our observations of a −2 mass shift on the free amino acid Ser, previously observed on free amino acids upon radiolysis (16), GSG and GTG both yielded the −2 carbonylation product. A mass shift of −16 was also observed on GSG, which has been previously seen (16). We hypothesize that this is a loss of oxygen and thus conversion of the middle residue from Ser to Ala.

Both GNG and GTG, residues containing polar side groups, had exact mass shifts of −48.021, a calculated loss of CH4O2 (54). This could correspond to radical-mediated decarboxylation of the C-terminus (−30, Fig. 3D), followed by oxygen loss to ultimately result in a C-terminal methyl group, though a further mass shift of −2 is unaccounted for. A mass shift of −4 was seen on the nonpolar residue-containing tripeptides GIG, GLG, and GVG. The small mass discrepancies here again indicate that more work is needed to confirm or update the suggested chemistries.

An exact mass shift of −87.03 was observed on the tripeptide GPG (Table S3, Fig. S10), which corresponds to a net loss of C3H5NO2 (54). This very likely corresponds to backbone cleavage and loss of all the atoms C-terminal to the Pro ring, via oxidation of the tripeptide to the 2-pyrrolidone derivative. Backbone cleavage via oxidation of Pro residues has been observed before(42, 55), and a mechanism has been defined(56). In this case, such cleavage would result in a mass shift of −86, leaving a hydrogen loss unaccounted for and the need for future experiments to confirm this possible similar product.

Modifications to sulfur-containing residues in tripeptides

Cys has been reported to dimerize to form cystine upon radiolysis via: 1) thiyl radical formation and reaction with oxygen, 2) hydroxylated or peroxylated side chain combination via loss of an H2O2, or 3) direct combination of thiyl radicals in conditions lacking oxygen (46, 47, 57-59). Consistent with this, we observed a strong signal at m/z 235.06, corresponding to +2 form of the dimerized cystine-containing tripeptide. Though it was present in the control sample, radiolysis strongly induced more cystine formation in a dose-dependent fashion. Concurrent with GCG disulfide dimerization, we identified sulfonic acid (+48) formation, addition of 3 oxygens to the sulfur atom. These results are consistent with those seen previously using an identical tripeptide and 137Cs exposure by Xu and Chance (60). In another study, Xu and Chance identified more oxidative modifications on GCG using MS in negative-mode; specifically, mass shifts of −16, −34, +32, +46, +64, and +80 (16). We posit that we did not observe these modifications due to our use of only positive-mode MS analysis for the tripeptides, given that a secondary positive-mode MS analysis in the same publication identified only the −16 mass shift and Cystine product formation (16).

The tripeptide GMG was highly modified (Tables 2, S3). Mass shifts of +16, −14, −32, and −50 were observed. The sulfoxide product, +16, was by far the strongest signal (Table S3). The −32 and −14 mass shifts were identified previously by Xu and Chance using GMG and 137Cs(16). The −14 product corresponds to decarboxylation (–30) followed by oxidation (+16). The −32 product results from loss of a methanesulfinyl group followed by aldehyde formation at the γ-carbon (16). Exact mass measurements using high-resolution MS confirm that the mass shift of −32.008 corresponds precisely to this structural difference. Despite the reactivity of GMG, decarboxylation of the C-terminus was not identified. This is likely due to the strong formation of the −14 product, for which the decarboxylation is a reaction intermediate. Finally, a product with a mass shift −50.019 was identified (Table S2), which has not been reported before. Reported elemental composition for this mass shift is CH6S (54), which we propose is a loss of these atoms from the Met side chain.

Modifications to aromatic residues in tripeptides

On GYG and GFG, only hydroxylation (+16) and decarboxylation (–30) were identified (Table 2). The tripeptide GWG could only be solubilized in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) due to its strong hydrophobicity. When diluted in dH2O to a working concentration of 50 μM, this resulted in 0.8% DMSO being present during IR exposure. In order to benchmark possible DMSO-dependent-differences in response rate, GIG and GTG were also irradiated in 0.8% DMSO and the response curves were compared to their respective curves without DMSO (Figure S7, Table S4). Under these conditions, GIG and GTG were similar in reactivity rate to their rate without added DMSO. DMSO can modify Trp to form 2-hydroxy-Trp in the presence of HCl as well as DMSO (61). With these caveats in mind, the sensitivity of GWG in DMSO was much greater than that of the rest of the tripeptides. Signal was lost at a dose of 200 Gy, a result more similar to the more highly-reactive free amino acids than to the tripeptides (Fig. S7, Tables 2, S3). Mass shifts of +16n were identified on GWG, up to n=3, similar to what was observed on free Trp. These likely include the products hydroxytryptophan (+16), dihydroxytryptophan (+32), and N-formylkynurenine (+32) (34, 48). Two unique products were identified on GWG, mass shifts of +62 and +82. We hypothesize that +62 is a result of four +16n oxidative events concurrent with carbon-carbon double bond formation somewhere in the molecule (−2). In contrast +82 may correspond to a product in which there are five +16 events in total as well as hydrogen atom addition across a double bond (+2). Xu and Chance also identified mass shifts of +16n up to n=5 when exposing the tripeptide GWG to radiolysis (17). Our identification of +16n mass shifts (with minor adducts or losses) up to n=5 here corroborates this data. In general, our data highlight the fact that one must pay attention to all chemical species present in the mixture when irradiation is performed, as even small amounts of solvents or buffers may make a large difference in the results obtained.

CONCLUSIONS

We have begun to study, in a methodical fashion, the effect of Linac-produced IR on amino acids and tripeptides. Our goal is understanding the differences between simplified systems and systems of more complexity when exposed to IR. The ultimate goal is inferring testable biological implications from datasets such as that produced here. However, fundamental groundwork must first be done to lay foundations for further efforts. In this study, novel mass shifts were observed. In contrast, modifications observed in previous studies were not seen here. The results described herein stress that the IR sensitivity of amino acids is highly contextual. Incorporating amino acids into a simple tripeptide substantially reduces their sensitivities, a result observed here as well as in comparisons of these data to many other studies. Additionally, modification patterns obtained by exposing free amino acids to IR may not readily be extrapolated to irradiation of the same amino acid residues within peptides. This claim is supported by both quantitative (dose response rates) and qualitative (chemical modifications) variability observed between even the simple systems used in these experiments. Furthermore, variability in amino acid response is also evident when comparing published studies, likely due to differences in solution conditions, radiation source, or the exact amino acid sequence of the peptides used. Future work will continue to examine these differences and define the effect of IR on biological molecules in highly controlled and reproducible conditions. Overall, the results begin to provide a basis for identifying IR-related protein damage on a proteomic scale.

METHODS

Linac irradiation protocol

Stocks of amino acids were made at a concentration of 500 μM in 10 mL dH2O. Stocks were kept at −20 °C and thawed when necessary. The 500 ·M amino acid stocks were diluted 1:10 in 1 mL total dH2O in 1.8 mL Eppendorf tubes for each sample to be irradiated. The remaining volume in each tube was air. Stocks of tripeptides were made at a standard concentration of 10mg/mL, and diluted to 50·M using dH2O immediately prior to exposure. Samples were maintained at 4 °C and taken to a Varian 21EX clinical linear accelerator (Linac) for irradiation (~15 min duration each way). For each irradiation, the Linac was set to deliver a beam of electrons with 6 MeV of energy to uniformly irradiate all samples (a total of 14) at once. To accomplish this, a special high-dose mode called HDTSe− was utilized, which resulted in a dose rate to the samples of approximately 72 Gy/min.

The sample tubes were placed horizontally and submerged at a depth of 1.3 cm (measured to the center of the tube’s volume) in an ice-water filled plastic tank and set to a source-to-surface distance (SSD) of 61.7 cm. A 30 × 30 cm2 square field size was set at the Linac console, which gave an effective field size at this SSD of 18.5 × 18.5 cm2. This is ample coverage to provide a uniform dose to all of the 1.5 mL sample tubes. The monitor unit calculations (determination of the amount of time to leave the Linac on) were based on the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) Task Group 51 protocol for reference dosimetry(62). This is the standard method for determining dose per monitor unit in water for radiation therapy calculations. Once the dose was determined in the AAPM Task Group 51 reference protocol conditions (SSD = 100 cm and depth =10 cm), an ion chamber and water-equivalent plastic slabs were used to translate this dose to the specific conditions used in this project. Irradiation was performed while the samples remained submerged at a depth of 1.3 cm in water. After irradiation, samples were frozen at −20 °C until needed. The following amino acids were used: L-Isoleucine (Product #: I2752; Sigma-Aldrich), L-Proline (Product #: P0380; Sigma-Aldrich), and the remaining amino acids came from a L-amino acids kit (Product #: LAA-21; Sigma-Aldrich).

LC-assisted High-Resolution Electrospray Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry analysis of amino acids

LC-HR-ESI-TOF analysis of IR-dosed amino acids in water was done on Agilent LC/MSD TOF system (model 6210) equipped with 1200 series HPLC liquid handling system (Agilent Technologies). Measurements of compounds was conducted under positive or negative ion polarity, where 2μ1 of control or IR-exposed sample was injected from an autosampler vial sitting at 6°C into an isocratic 0.05 ml/min flow of 50:50 [Water / 0.1% Formic acid]:[Acetonitrile / 0.1% Formic acid]. The following instrumental parameters were used to generate the most optimum protonated [M+H+] or deprotonated [M-H−] ions under their respective acquisition polarity: Capillary voltage [3000V]; Drying gas [7 1/min]; Gas temperature [300°C]; Nebulizer [15psig]; Oct DC1 [35V] for positive and [−34V] for negative ionization; Fragmentor [140V]; Oct RF [200V]; Skimmer [60V]. Internal calibration was achieved with assisted spray of two reference masses, 112.9856 m/z and 1033.9881 m/z. Data was acquired in profile mode scanning from 50-1,600 AMU at 0.89 cycles per second and 10,000 transients per scan.

LC-assisted Ultra High-Resolution Electrospray Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry analysis of tripeptides

LC-UHR-ESI-Orbitrap analysis of IR-dosed tripeptides in water was done on Thermo Scientific LTQ-Orbitrap Elite™ system equipped with an IonMAX electrospray source. Measurements of compounds was conducted under positive ion polarity in profile mode either as a one scan or five scan event, where 2μl of control or IR-exposed sample was injected from an autosampler vial sitting at 6°C into an isocratic 0.05 ml/min flow of 50:50 [Water / 0.1% Formic acid] : [Acetonitrile / 0.1% Formic acid]. The one-scan event consisted of a continuous MS1 scanning at 120,000 resolution over 50-1,000 m/z mass range. The five-scan event consisted of continuous cycle of a single MS1 scan at 120,000 resolution over 50-400 m/z followed by four MS/MS scans on the four most abundant precursors observed in the preceding MS1 event. HCD-based fragmentation with a normalized collision energy of 35% and isolation width of 1.2Da was scanned into Orbitrap under 15,000 resolution. The following instrumental parameters were used to generate the most optimum protonated [M+H+] ions: Source voltage [3,800V]; Source heater [100°C]; Capillary temperature [320°C]; Sheath gas flow [15]; auxiliary gas flow [5]; S-lens RF level [35%]; Multipole RF Amplifier [600].

MS data analysis

Data processing of the single amino acids was executed using Analyst QS 1.1 (build:9865) software (Agilent Technologies) to extract unique masses observed in the spectrum. This semimanual analysis strategy was further complemented and verified with fully-automatic processing using Agilent’s MassHunter Workstation Qualitative Analysis software (version B.01.03, build: 1.3.157.0), where centroided data (filtered based on absolute peak height of 200 counts per second, minimum to differentiate peaks from the baseline on our instrument) was used to assign compounds from their molecular features and ultimately generate extracted ion abundance chromatograms (using original profile data) to aid in quantification and distribution over the whole IR dosage spectrum.

Data processing of the tripeptides was executed using Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser. A boxcar smoothing of 7 and ppm window of 4 amu was used to extract ion chromatograms for the unmodified version of the tripeptide and all modifications observed. Modifications were identified by examining spectra averaged over the injection curve per sample, with a S/N threshold of > 1.0% for peak identification. Whether the 1+ or the 2+ variant of the tripeptide was used for quantification is specified in Table S3, when both forms were identified. Area under extracted ion chromatograms was calculated using Qual Browser’s automatic peak picking algorithm.

Relative reactivity rates were calculated by fitting linear trendlines to the obtained data as specified. For the amino acids, the doses including 0, 100, and 200 Gy were used. For tripeptides, doses across the full range (0-1000 Gy) of IR treatments were used. No fitting was performed for modification appearance rates.

Tripeptide volumes were determined using an online tool accessible at http://biotools.nubic.northwestern.edu/proteincalc.html (53).

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Free amino acid IR sensitivity and modification patterns. Collected using electrospray ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Each amino acid is shown both for positive and negative mode on individual sheets. Below are the automatically extracted masses, their retention times, peak heights, and identified adducts. Above, values for quantification were built on extracted ion chromatograms of the specified masses (the example of the unmodified is given in every case). In many cases, shown in bolded red, the automatic peak picking informed the masses to manually extract. Masses that were extracted and quantified above but not bolded in red below were chosen based on literature reports, cited in the main text. The data here were used to build charts for Figures S1-S3. All masses displayed are m/z (Da/charge state), though charge states of only +1 or −1 were observed.

Table S2. Data used for low abundance tripeptides, including GQG, GDG, GPG, and GKG. Each was tested by concentration from stock exposure 2x, 5x, and 10x. For all of these, the 10-fold concentration was used as representative, and the data from those exposures is used in Figs. 3A-C. All masses displayed are m/z (Da/charge state).

Table S3. Tripeptide IR sensitivity and modification patterns. Collected using electrospray ionization-orbitrap mass spectrometry. Each tripeptide is shown on a different sheet. Charts are extracted ion chromatograms for the specified species for each dosage, used for the quantification tables shown below them. The extracted mass is displayed above the respective table per species. The data here were used to build the charts for Figures S8-10. All masses displayed are m/z (Da/charge state).

Table S4. Data used for tripeptides in DMSO figure. Each of the three tripeptides is shown on a separate sheet.

Figures S1-S3. Product formation over a range of 0Gy-1000Gy for the free amino acids. Known modifications are shown as atomic adducts, whereas unknown modifications are shown as mass shifts. The y-axes are unitless, and are raw signal intensities for the listed modifications.

Fig. S4. Clustering and ESI-TOF data demonstrating sensitivities of nonpolar, polar, charged, and aromatic free amino acids.

Figure S5. Correlations of sensitivities (slope over linear range of signal loss for unmodified versions, all x-axes) with physicochemical properties for free amino acids.

Figure S6. Reproducibility of experiments. Top left, three technical replicates (same sample, analyzed thrice with same instrumental method, processing, etc. post-irradiation) of GKG at low concentration. Top right and bottom, experimental replicates (samples independently made up, exposed, and analyzed). Top right, GMG twice independently diluted to 50μM, exposed to IR and analyzed, approximately 1 month apart. Bottom left, GVG twice independently diluted to 50μM, exposed to IR and analyzed, approximately 1 month apart.

Figure S7. Comparison of sensitivity for two tripeptides in dH2O and 0.8% DMSO. All tripeptides are 50μM.

Figures S8-S10. Product formation over a range of 0Gy-1000Gy for the tripeptides. Known modifications are shown as atomic adducts, whereas unknown modifications are shown as mass shifts. The y-axes are unitless, and are raw signal intensities for the listed modifications.

Figure S11. Correlations of relative sensitivities (slope over linear range of signal loss for unmodified versions) with physicochemical properties for free amino acids.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge funding to B.B.M., G.S., S.T.B., M.M.C., and M.R.S. from the USDOD, Homeland DTRA grant no. HDTRA1-16-1-0049 and to S.T.B. and M.M.C from the NIH grant no. GM112575. S.T.B. also received funding from the Morgridge Biotechnology Fellowship from the Vice Chancellor's Office for Research and Graduate Education and the UW Biotechnology Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daly MJ. A new perspective on radiation resistance based on Deinococcus radiodurans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(3):237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krisko A, Radman M. Biology of extreme radiation resistance: the way of Deinococcus radiodurans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan MA, Lawrence TS. Molecular Pathways: Overcoming Radiation Resistance by Targeting DNA Damage Response Pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(13):2898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto T, Kunieda T. DNA Protection Protein, a Novel Mechanism of Radiation Tolerance: Lessons from Tardigrades. Life (Basel). 2017;7(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung KW, Lim S, Bahn YS. Microbial radiation-resistance mechanisms. J Microbiol. 2017;55(7):499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranawat P, Rawat S. Radiation resistance in thermophiles: mechanisms and applications. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;33(6):112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuryak I, Matrosova VY, Gaidamakova EK, Tkavc R, Grichenko O, Klimenkova P, et al. Microbial cells can cooperate to resist high-level chronic ionizing radiation. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung KW, Yang DH, Kim MK, Seo HS, Lim S, Bahn YS. Unraveling Fungal Radiation Resistance Regulatory Networks through the Genome-Wide Transcriptome and Genetic Analyses of Cryptococcus neoformans. MBio. 2016;7(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anno GH, Young RW, Bloom RM, Mercier JR. Dose response relationships for acute ionizing-radiation lethality. Health Phys. 2003;84(5):565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Islam MT. Radiation interactions with biological systems. Int J Radiat Biol. 2017;93(5):487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies MJ. The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703(2):93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies MJ. Reactive species formed on proteins exposed to singlet oxygen. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies KJ, Delsignore ME, Lin SW. Protein damage and degradation by oxygen radicals. II. Modification of amino acids. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(20):9902–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stadtman ER. Oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins by radiolysis and by metal-catalyzed reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:797–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stadtman ER, Levine RL. Free radical-mediated oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins. Amino Acids. 2003;25(3–4):207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu G, Chance MR. Radiolytic modification of sulfur-containing amino acid residues in model peptides: fundamental studies for protein footprinting. Anal Chem. 2005;77(8):2437–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu G, Chance MR. Hydroxyl radical-mediated modification of proteins as probes for structural proteomics. Chem Rev. 2007;107(8):3514–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benon HJ Bielski DEC, Ross Alberta B., Arudi Ravindra L.. Reactivity of HO2/O–2 Radicals in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 1985;14(4):1041–100. [Google Scholar]

- 19.George V Buxton CLG, Phillips Helman W, Ross Alberta B.. Critical Review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (·OH/·O─) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 1988;17(2):513–886. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaur P, Kiselar JG, Chance MR. Integrated algorithms for high-throughput examination of covalently labeled biomolecules by structural mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81(19):8141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu G, Takamoto K, Chance MR. Radiolytic modification of basic amino acid residues in peptides: probes for examining protein-protein interactions. Anal Chem. 2003;75(24):6995–7007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu G, Chance MR. Radiolytic modification of acidic amino acid residues in peptides: probes for examining protein-protein interactions. Anal Chem. 2004;76(5):1213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saladino J, Liu M, Live D, Sharp JS. Aliphatic peptidyl hydroperoxides as a source of secondary oxidation in hydroxyl radical protein footprinting. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20(6):1123–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan PE, Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Quantification of hydroxyl radical-derived oxidation products in peptides containing glycine, alanine, valine, and proline. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(2):328–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Meutter P, Camps J, Delcloo A, Termonia P. Source localisation and its uncertainty quantification after the third DPRK nuclear test. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams M, Sizemore DC. Biologic, Chemical, and Radiation Terrorism Review StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jorgensen TJ. Predicting the Public Health Consequences of a Nuclear Terrorism Attack: Drawing on The Experiences of Hiroshima and Fukushima. Health Phys. 2018;115(1):121–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smirnova OA, Cucinotta FA. Dynamical modeling approach to risk assessment for radiogenic leukemia among astronauts engaged in interplanetary space missions. Life Sci Space Res (Amst). 2018;16:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jandial R, Hoshide R, Waters JD, Limoli CL. Space-brain: The negative effects of space exposure on the central nervous system. Surg Neurol Int. 2018;9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruckbauer ST, Trimarco JD, Senn K, Bushnell B, Lipzen A, Blow M, Martin J, Schackwitz W, Pennacchio C, Wood EA, Culberson WS, and Cox MM Directed evolution of extreme resistance to ionizing radiation in E. coli after 50 cycles of selection. Submitted. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies MJ, and Dean RT Radical-Mediated Protein Oxidation: Oxford University Press; 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamyatnin AA. Protein volume in solution. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1972;24:107–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157(1):105–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ERIC L FINLEY JD, CROUCH ROSALIEK, SCHEY KEVINL . Identification of tryptophan oxidation products in bovine a-crystallin. Protein Science. 1998;7:2391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinecke JW, Li W, Daehnke HL, 3rd, Goldstein JA. Dityrosine, a specific marker of oxidation, is synthesized by the myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide system of human neutrophils and macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(6):4069–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huggins TG, Wells-Knecht MC, Detorie NA, Baynes JW, Thorpe SR. Formation of o-tyrosine and dityrosine in proteins during radiolytic and metal-catalyzed oxidation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(17):12341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marquez LA, Dunford HB. Kinetics of oxidation of tyrosine and dityrosine by myeloperoxidase compounds I and II. Implications for lipoprotein peroxidation studies. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(51):30434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maskos Z, Rush JD, Koppenol WH. The hydroxylation of phenylalanine and tyrosine: a comparison with salicylate and tryptophan. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;296(2):521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Easton CJ. Free-Radical Reactions in the Synthesis of alpha-Amino Acids and Derivatives. Chem Rev. 1997;97(1):53–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrison WM. Reaction mechanisms in the radiolysis of peptides, polypeptides, and proteins. Chem Rev. 1987;87(2):381–98. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amici A, Levine RL, Tsai L, Stadtman ER. Conversion of amino acid residues in proteins and amino acid homopolymers to carbonyl derivatives by metal-catalyzed oxidation reactions. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(6):3341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dean RT, Wolff SP, McElligott MA. Histidine and proline are important sites of free radical damage to proteins. Free Radic Res Commun. 1989;7(2):97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Requena JR, Chao CC, Levine RL, Stadtman ER. Glutamic and aminoadipic semialdehydes are the main carbonyl products of metal-catalyzed oxidation of proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(1):69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S, Schoneich C, Borchardt RT. Chemical pathways of peptide degradation. VIII. Oxidation of methionine in small model peptides by prooxidant/transition metal ion systems: influence of selective scavengers for reactive oxygen intermediates. Pharm Res. 1995;12(3):348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogt W Oxidation of methionyl residues in proteins: tools, targets, and reversal. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18(1):93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armstrong DA. Applications of Pulse Radiolysis for the Study of Short-Lived Sulphur Species In: Chatgilialoglu C, Asmus K-D, editor. Sulfur-Centered Reactive Intermediates in Chemistry and Biology. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Sonntag C Free-radical reactions involving thiols and disulphides Sulfur-centered reactive intermediates in chemistry and biology: Springer; 1990. p. 359–66. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stadtman ER. Role of oxidized amino acids in protein breakdown and stability In: Klinman JP, editor. Methods in Enzymology: Elsevier, Inc.; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawkins CL, Davies MJ Generation and propagation of radical reactions on proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1504:196–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uchida K, Kawakishi S. Selective oxidation of imidazole ring in histidine residues by the ascorbic acid-copper ion system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;138(2):659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao PS, Simic M, Hayon E Pulse radiolysis study of imidazole and histidine in water. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1975;79. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tomita M, Masachika I, Tyunosin U Sensitized photooxidation of histidine and its derivatives. Products and mechanism of the reaction. Biochemistry. 1969;8:5149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harpaz Y, Gerstein M, & Chothia C Volume Changes on Protein Folding. Structure. 1994;2(7):641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patiny L, Borel A. ChemCalc: a building block for tomorrow's chemical infrastructure. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53(5):1223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuessler H, Schilling K. Oxygen effect in the radiolysis of proteins. Part 2. Bovine serum albumin. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1984;45(3):267–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uchida K, Kato Y, Kawakishi S. A novel mechanism for oxidative cleavage of prolyl peptides induced by the hydroxyl radical. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;169(1):265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lal M Radiation induced oxidation of sulphydryl molecules in aqueous solutions. A comprehensive review. Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 1994;43(6):595–611. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dewey DL, Beecher J. Interconversion of cystine and cysteine induced by x-rays. Nature. 1965;206(991):1369–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Owen TC, Brown MT. Radiolytic oxidation of cysteine. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1969;34(4):1161–2. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu G, Chance MR. Radiolytic modification and reactivity of amino acid residues serving as structural probes for protein footprinting. Anal Chem. 2005;77(14):4549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Savige WE, Fontana A. Oxidation of tryptophan to oxindolylalanine by dimethyl sulfoxide-hydrochloric acid. Selective modification of tryptophan containing peptides. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1980;15(3):285–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Almond PR, Biggs PJ, Coursey BM, Hanson WF, Huq MS, Nath R, et al. AAPM's TG-51 protocol for clinical reference dosimetry of high-energy photon and electron beams. Med Phys. 1999;26(9):1847–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Free amino acid IR sensitivity and modification patterns. Collected using electrospray ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Each amino acid is shown both for positive and negative mode on individual sheets. Below are the automatically extracted masses, their retention times, peak heights, and identified adducts. Above, values for quantification were built on extracted ion chromatograms of the specified masses (the example of the unmodified is given in every case). In many cases, shown in bolded red, the automatic peak picking informed the masses to manually extract. Masses that were extracted and quantified above but not bolded in red below were chosen based on literature reports, cited in the main text. The data here were used to build charts for Figures S1-S3. All masses displayed are m/z (Da/charge state), though charge states of only +1 or −1 were observed.

Table S2. Data used for low abundance tripeptides, including GQG, GDG, GPG, and GKG. Each was tested by concentration from stock exposure 2x, 5x, and 10x. For all of these, the 10-fold concentration was used as representative, and the data from those exposures is used in Figs. 3A-C. All masses displayed are m/z (Da/charge state).

Table S3. Tripeptide IR sensitivity and modification patterns. Collected using electrospray ionization-orbitrap mass spectrometry. Each tripeptide is shown on a different sheet. Charts are extracted ion chromatograms for the specified species for each dosage, used for the quantification tables shown below them. The extracted mass is displayed above the respective table per species. The data here were used to build the charts for Figures S8-10. All masses displayed are m/z (Da/charge state).

Table S4. Data used for tripeptides in DMSO figure. Each of the three tripeptides is shown on a separate sheet.

Figures S1-S3. Product formation over a range of 0Gy-1000Gy for the free amino acids. Known modifications are shown as atomic adducts, whereas unknown modifications are shown as mass shifts. The y-axes are unitless, and are raw signal intensities for the listed modifications.

Fig. S4. Clustering and ESI-TOF data demonstrating sensitivities of nonpolar, polar, charged, and aromatic free amino acids.

Figure S5. Correlations of sensitivities (slope over linear range of signal loss for unmodified versions, all x-axes) with physicochemical properties for free amino acids.

Figure S6. Reproducibility of experiments. Top left, three technical replicates (same sample, analyzed thrice with same instrumental method, processing, etc. post-irradiation) of GKG at low concentration. Top right and bottom, experimental replicates (samples independently made up, exposed, and analyzed). Top right, GMG twice independently diluted to 50μM, exposed to IR and analyzed, approximately 1 month apart. Bottom left, GVG twice independently diluted to 50μM, exposed to IR and analyzed, approximately 1 month apart.

Figure S7. Comparison of sensitivity for two tripeptides in dH2O and 0.8% DMSO. All tripeptides are 50μM.

Figures S8-S10. Product formation over a range of 0Gy-1000Gy for the tripeptides. Known modifications are shown as atomic adducts, whereas unknown modifications are shown as mass shifts. The y-axes are unitless, and are raw signal intensities for the listed modifications.

Figure S11. Correlations of relative sensitivities (slope over linear range of signal loss for unmodified versions) with physicochemical properties for free amino acids.