Abstract

Background: In anal cancer, there are no markers nor other laboratory indexes that can predict prognosis and guide clinical practice for patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation. In this study, we retrospectively investigated the influence of immune inflammation indicators on treatment outcome of anal cancer patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Methods: All patients had a histologically proven diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal/margin treated with chemoradiotherapy according to the Nigro’s regimen. Impact on prognosis of pre-treatment systemic index of inflammation (SII) (platelet x neutrophil/lymphocyte), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were analyzed.

Results: A total of 161 consecutive patients were available for the analysis. Response to treatment was the single most important factor for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). At univariate analysis, higher SII level was significantly correlated to lower PFS (p<0.01) and OS (p=0.046). NLR level was significantly correlated to PFS (p=0.05), but not to OS (p=0.06). PLR level significantly affected both PFS (p<0.01) and OS (p=0.02). On multivariate analysis pre-treatment, SII level was significantly correlated to PFS (p=0.0079), but not to OS (p=0.15). We developed and externally validated on a cohort of 147 patients a logistic nomogram using SII, nodal status and pre-treatment Hb levels. Results showed a good predictive ability with C-index of 0.74. An online available calculator has also been developed.

Conclusion: The low cost and easy profile in terms of determination and reproducibility make SII a promising tool for prognostic assessment in this oncological setting.

Keywords: NLR, PLR, SII, anal cancer, prognostic factors

Introduction

Anal cancer is an uncommon cancer, with an incidence of 1–2 new cases/100,000 per year worldwide.1 Etiologically, 80–90% of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) type infections, in particular, HPV 16.2,3 In developed countries, the incidence of anal SCC is increasing by 1–3% per year, parallel to a higher incidence of HPV infection.4

In the past, the standard of care for invasive anal carcinoma was represented by abdominoperineal resection (APR); local recurrence rates were high and the morbidity related to permanent colostomy was considerable.5 In 1974, Nigro and colleagues described complete tumor regression in some patients treated with preoperative 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy (CT-RT).6 Successively, randomized trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of CT-RT supported the use of this combined modality approach.7,8

Nowadays, the standard of treatment for localized disease is still represented by RT in combination to CT with 5-FU and mitomycin, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 60%.8 Abdominoperineal resection and colostomy are limited to patients with locally biopsy-proven progressive or recurrent disease after CT-RT.9 The standard of care in metastatic disease is combined Cisplatin and 5-FU. The 5-year survival rate is 15%, with a median survival time of 12 months.10,11 Outcomes for patients with anal cancer depend on tumor characteristics, clinical stage at presentation, patient-related factors and laboratory parameters; in particular, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer trial 22861 (EORTC 22861) has demonstrated that skin ulceration, nodal involvement and male gender were the most important prognostic factors for local control and survival.8

In anal cancer, however, no markers or other laboratory indexes are validated and used in clinical practice for predicting the prognosis and appropriately guiding the clinical practice. In the last few years, research interest has grown on the correlation between cancer and inflammation, which is now recognized as a hallmark of cancer development and progression.12 The association between clinical outcomes and local and systemic inflammation has been demonstrated in different malignancies. In particular, neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets and acute-phase proteins (such as C-reactive protein) have been evaluated in various cancer types, and high levels of these biomarkers have been proven to predict for poorer prognosis and response to treatment.13–17

Recently, Martin et al.18 and the ACT I19 trial have showed that in SCC a higher peripheral leukocytosis was associated with a poor outcome in patients treated with CT-RT. Moreover, Martin et al. demonstrated an inverse correlation between leukocytosis and intratumoral CD8+ in this setting of patients.

Several inflammation and immune-based prognostic scores, such as lymphocyte count, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), have been developed to predict survival and recurrence in cancer patients.20,21 For SCC, Toh et al.22 demonstrated that pretreatment NLR may be a predictor of outcome in this setting of patients.

Another interesting parameter is represented by the systemic index of inflammation (SII) given by the combination of platelet count and NLR. Since SII is determined by three different types of inflammatory cells, it can be regarded as a reliable surrogate for systemic inflammatory response mirroring the balance between tumor and host. The prognostic role of SII has been explored in several tumors and it has been demonstrated to be strongly associated to poor outcome when it is increased.16,23

In this study, we retrospectively investigated the influence of immune inflammation indicators on the treatment outcome of anal cancer patients undergoing concurrent CT-RT.

Patients and methods

For the present study, all medical records were retrieved from the databases of 3 different Institutions.

Data were entered into electronic data files by coinvestigators from each center and checked at the data management center for missing information and internal consistency. Written informed consent for treatment was obtained from all patients. The Ethical Review Board of C.E.ROM (Comitato Etico della ROMagna) approved the present study. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under good clinical practice conditions.

All patients had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of SSC located in either the anal canal or margin. We included patients with clinical stage T1-T4, N0-N3, M0 (tumor stage was defined following the indications of the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 2002 version). Patients with clinical T1N0 tumors of the anal margin were excluded because they were treated with local excision.

All patients were treated with CT-RT according to the Nigro’s regimen between 2005 and 2016.

CT consisted of 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2/day) given as continuous infusion for 96 hrs (days 1–5 and 29–33) combined with mitomycin C (10 mg/m2) given as bolus (days 1 and 29). Mitomycin C was capped at 20 mg maximum dose. A total of 2 concurrent cycles were planned for each patient.

Patients were treated with two different RT approaches. In the first institution, patients were submitted to a simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) RT approach and dose prescription was set according to the RTOG 0529 indications based on clinical stage at presentation.20,24,25 Patients with cT2N0 disease were given 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions (1.8 Gy daily) for the primary anal tumor, while 42 Gy in 28 fractions (1.5 Gy daily) for the elective nodal volume. Patients presenting with cT3-T4/N0-N3 disease were prescribed 54 Gy in 30 fractions (1.8 Gy daily) to the gross tumor volume, while 50.4 Gy in 30 fractions (1.68 Gy daily) or 54 Gy in 30 fractions (1.8 Gy daily) to the gross nodal disease if sized <3 cm or >3 cm, respectively. Elective nodal volume was prescribed 45 Gy in 30 fractions (1.5 Gy daily).26,27 Details and results of this treatment strategy have been previously described.23,24,27 In the second and third institution, the patients were given a first sequence of RT 45 Gy in 25 fractions (1.8 Gy daily) delivered over 5 weeks to the macroscopic primary and nodal tumor and prophylactic volumes (pelvic and inguinal nodes, ischio-anal fossa and mesorectum). In the second sequence, a further dose of 9–14.4 Gy in 5–8 fractions was delivered sequentially to the macroscopic disease up to a total nominal dose of 54–59.4 Gy.

Pre-treatment evaluation included: chest, abdomen and pelvis computed tomography scan and a magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic region.

Response to treatment was assessed at 2 time-points, namely at 6 weeks and at 3 months of CT-RT.

Validation cohort consisted of 147 patients and was obtained by three other institutions in France and Italy. Treatment specifics for each institution were similar to those previously reported, with same regimens of chemotherapy. The radiotherapy approach used was a sequential boost strategy similar to the one used in the second and third institution.

Statistical analysis

Primary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. PFS was defined as the time from start of treatment to progression (both clinical or radiological), or death from any cause. OS was defined as time from start of treatment to death from any cause. Response to treatment was assessed using the RECIST criteria. The time-to-event functions were estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and differences between covariates were addressed with the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional-hazard models were also used to estimate the hazard ratios (HR) and the associated 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We used both the forward and backward approach to create multivariable models. Wald test and likelihood ratio tests for the case of nested models were used to assess significance of both single covariates and the entire models. Proportional hazard assumption was tested with visual inspection of log–log survival curves, plotted scaled Schoenfeld residuals and global Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Collinearity among independent variables was investigated with ANOVA and Fisher’s exact test of difference between means. Investigated variables included age, gender, tumor and nodal stage, response to treatment, overall treatment duration, HIV positivity, grading, total delivered dose of RT. Tumor and nodal stage were recorded using the AJCC cancer staging 7h edition. Response was evaluated using the RECIST criteria. Absolute values of pre-treatment platelets, lymphocytes and neutrophils were assessed 6 days before the start of treatment. NLR and PLR were both obtained by dividing the number of neutrophils or platelets by the number of lymphocytes. SII was obtained by using the formula: (neutrophils × platelets)/lymphocytes. ROC curves were constructed to assess the best cut-off point for categorization of continuous variables. Considering the remarkable impact of response to CT-RT on both PFS and OS and the poor prognosis of patients who did not respond to treatment, we created a predictive model for progressive disease (PD), in the attempt to identify those patients with a worse prognosis. We used unconstrained logistic regression, considering stabilization or progression (SD or PD) as 1, and complete and partial responses (CR or PR) as 0. First, all covariates were tested in univariate models, and then a multivariate model was developed, using both the forward and backward method. Collinearity was assessed as above. Decision on which covariate to include in the final model was made taking into account their statistical significance, the magnitude of change induced in the logit induced and their clinical plausibility. A nomogram was finally developed based on the final multivariate logistic model. Considering the wide variability in the SII index, a natural logarithmic transformation was applied to this variable. Predicted probabilities were tested against the observed probabilities in the validation set. Somer’s D, Harrell C index, Spiegelhalter Z-test and Brier score were used to evaluate the discrimination of the model. 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of the C index were calculated with bootstrap. Calibration plot was assessed visually. All analyses were performed with “rms”, “pROC” and “survival” packages of R software environment (https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

A total of 161 consecutive patients with anal cancer were available for the Development Set (DS) and 147 for the Validation Set (VS).

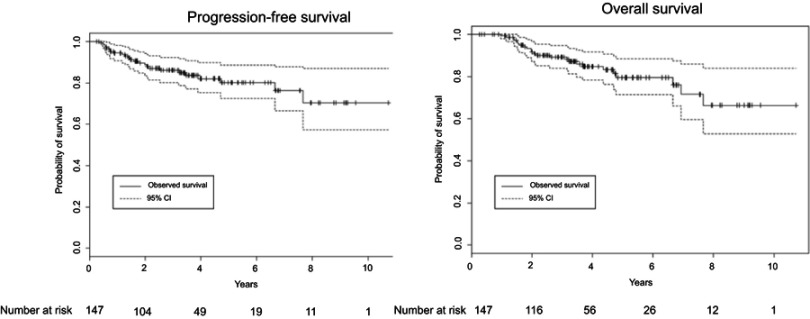

Patients and treatment characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and S1, respectively. After a median follow-up of 27 months (range: 1–30) in the DS, we observed 3-year PFS and OS of 67.5% (95% CI:64.2–80.5%) and 83.1% (95% CI:76.4–90.5%), respectively. Five-year PFS and OS were 64% (95% CI:64.2–80.5%) and 76.1% (95% CI:67.3–86.0%) (Figure S1). PFS and OS in the VS were similar but with slightly better results (Figure S2). 3-year PFS and OS were, respectively, 86.1% (95% CI: 80.3–92.3%) and 89.1% (95% CI:83.9–94.7%). Five-year PFS and OS were 80.2% (95% CI: 72.6–88.6%) and 79.5% (95% CI:71.5–88.5%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Development set, n=161 | Validation set, n=147 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean | 62 | 68.8 | 0.098 |

| Range | 36–83 | 42–91 | ||

| Sex | Male | 26 (16.2) | 35 (23.8) | 0.115 |

| Female | 135 (83.8) | 112 (82.2) | ||

| Pre-treatment Hb | Mean | 13.1 | 13.2 | 0.339 |

| Range | 7.6–16.8 | 8.8–17.2 | ||

| T-stage | T1 | 14 (8.7) | 7 (4.7) | 0.067 |

| T2 | 90 (56.0) | 71 (48.4) | ||

| T3 | 40 (24.8) | 35 (23.8) | ||

| T4 | 15 (9.3) | 27 (18.4) | ||

| NA | 2 (1.2) | 7 (4.7) | ||

| N-stage | N0 | 91 (56.6) | 74 (50.3) | 0.012 |

| N1 | 26 (16.1) | 31 (21.1) | ||

| N2 | 34 (21.1) | 19 (12.9) | ||

| N3 | 10 (6.2) | 23 (15.7) | ||

| Global stage | I | 13 (8.1) | 9 (6.1) | 0.104 |

| II | 72 (44.7) | 47 (32) | ||

| IIIA | 29 (18.0) | 39 (26.5) | ||

| IIIB | 46 (28.6) | 45 (30.6) | ||

| NA | 1 (0.6) | 7 (4.8) | ||

| Grade | G1 | 12 (7.5) | 32 (21.8) | <0.01 |

| G2 | 86 (53.4) | 52(35.3) | ||

| G3 | 45 (27.9) | 33 (22.5) | ||

| NA | 18 (11.2) | 30 (20.4) |

Table S1.

Treatment characteristics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| SIB | 96 (59.6) |

| PTV dose-tumor (Gy) | |

| 54 Gy/30 fractions | 58 (60.4) |

| 50.4 Gy/28 fractions | 38 (39.6) |

| PTV dose-positive nodes (Gy) | |

| 54 Gy/30 fractions | 8 (21.6) |

| 50.4 Gy/30 fractions | 29 (78.4) |

| PTV dose-negative nodes (Gy) | |

| 45 Gy/30 fractions | 58 (60.4) |

| 42 Gy/30 fractions | 38 (39.6) |

| Sequential boost | 65 (40.4) |

| First-phase PTV | |

| 45 Gy/25 fractions | 65 (100) |

| Sequential boost PTV | |

| Yes | 63 (96.9) |

| 9 Gy | 40 (61.5) |

| 14.4 Gy | 23 (35.4) |

| No | 2 (3.1) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| 5-FU + MMC | 158 (98.1) |

| No | 3 (1.9) |

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; MMC, mitomycin; SIB, simultaneous integrated boost, PTV, planning target volume.

Table S2 shows the results of the univariate analyses presented in the previous study.28

Table S2.

Results of univariate analysis of the previous study

| PFS | OS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | P-value | HR | (95% CI) | P-value | |

| SD+PD vs CR | 41.8 | 40.9–42.7 | <0.0001 | 53.3 | 52.1–54.3 | <0.0001 |

| PR vs CR | 2.96 | 1.35–6.54 | 0.0071 | 2.45 | 0.82–7.31 | 0.1 |

| Hb as a continuous variable | 0.57 | 0.39–0.85 | 0.049 | 0.53 | 0.29–0.96 | 0.047 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; Hb, hemoglobin; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

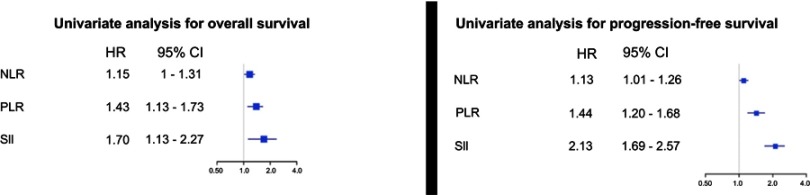

Considering SII, PLR and NLR as continuous variables, a higher baseline value of these indexes was associated to a higher risk of treatment failure and death (Figure 1). A higher SII level was significantly correlated to lower PFS (HR:2.13; 95% CI:1.69–2.59%; p<0.01) and OS (HR:1.70; 95% CI:1.13–2.27%; p=0.046). NLR level was significantly correlated to PFS (HR:1.13; 95% CI:1.01–1.26%; p=0.05), but not to OS (HR: 1.15; 95% CI:1.0–1.315; p=0.06). PLR level significantly affected both PFS (HR:1.44; 95% CI:1.20–1.68%; p<0.01) and OS (HR:1.43; 95% CI:1.13–1.73%; p=0.02).

Figure 1.

Univariate analysis of progression-free survival and overall survival.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic index of inflammation.

Considering platelet, neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, data showed that only platelet values could predict for PFS (HR:1.71; 95% CI:1.22–2.38%). None was predictive for OS.

On multivariate analysis, response to treatment maintained a significant correlation to PFS (less than PR vs CR; HR:30.03; 95% CI:7.97–113.2%; p<0.0001) (PR vs CR HR:2.44; 95% CI:1.05–5.71%; p=0.0028) and OS (less than PR vs CR; HR:43.82; 95% CI:10.03–191.42%; p<0.0001) (PR vs CR: HR:3.51;95% CI-1.01–12.18%;p=0.0492). Pre-treatment SII level had a significant correlation to PFS (HR:1.57;95% CI:1.21–2.03; p=0.007), but not to OS (HR:1.21;95% CI:0.85–1.80; p=0.15).

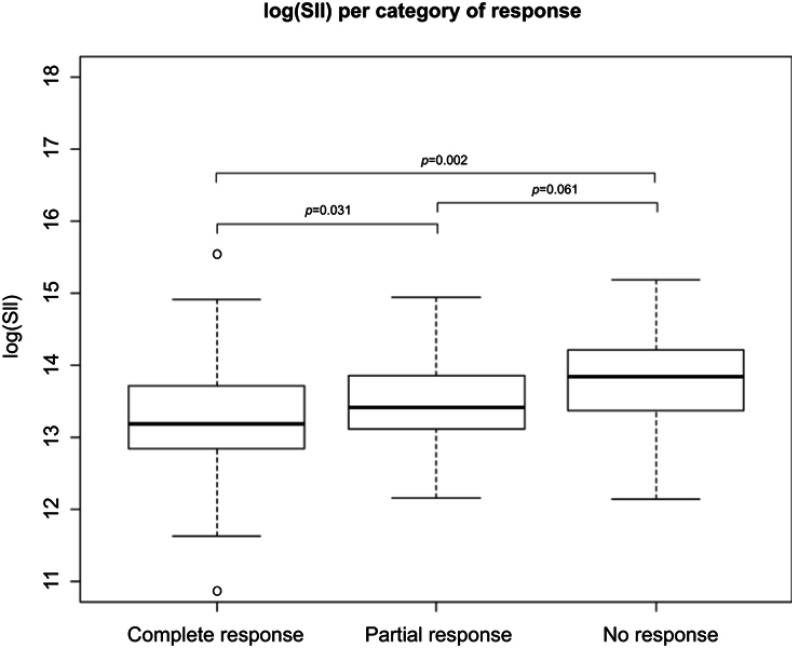

In the development cohort, the comparison of mean pre-treatment SII values in patients having CR (mean: 696,542) or PR (mean: 627,892) and in those having SD + PD (mean: 1,270,000) showed a trend for a significant difference. However, if the same analysis was applied to the entire population, a significant difference in baseline SII was present (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

SII value for category of response.

Abbreviation: SII, systemic index of inflammation.

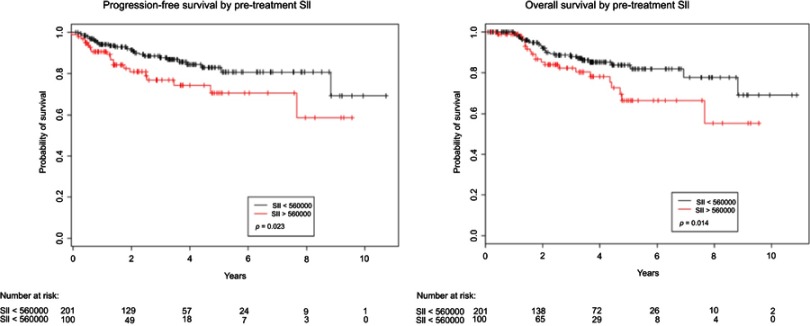

ROC analysis to identify the best cut-off point was performed on the entire population. SII obtained an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.61. Setting the cut-off point at 560,000, patients with higher pre-treatment SII had a 5-year PFS of 73.2%, compared to 85.4% for those with lower values (Figure 3 (left), log-rank test p-value =0.023). Five-year OS was 65.7% for patients having SII ≥560,000, and 83.2% for those having baseline SII <560,000 (Figure 3 (right), log-rank test p-value=0.014).

Figure 3.

Progression-free survival (left) and overall survival (right) by pre-treatment SII.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic index of inflammation.

Considering all variables potentially predictive for response, univariate analysis showed a high risk of treatment failure and death connected to SII values (OR:3.03; 95% CI:2.24–3.84%), nodal involvement (OR:13.73; 95% CI:11.64–15.82%), baseline hemoglobin level (OR:0.61; 95% CI:0.24–0.98%), NLR (OR:1.24; 95% CI:1.01–1.47%) and PLR (OR:1.65; 95% CI:1.20–2.11%). SII (OR: 2.99; 95% CI: 2.04–3.94%) and lymphnode status (OR: 5.88; 95% CI: 3.37–8.40%) were the only predictors of response to CT-RT in multivariate analysis.

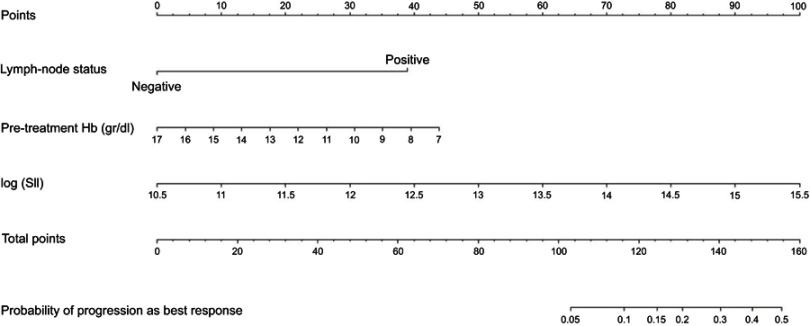

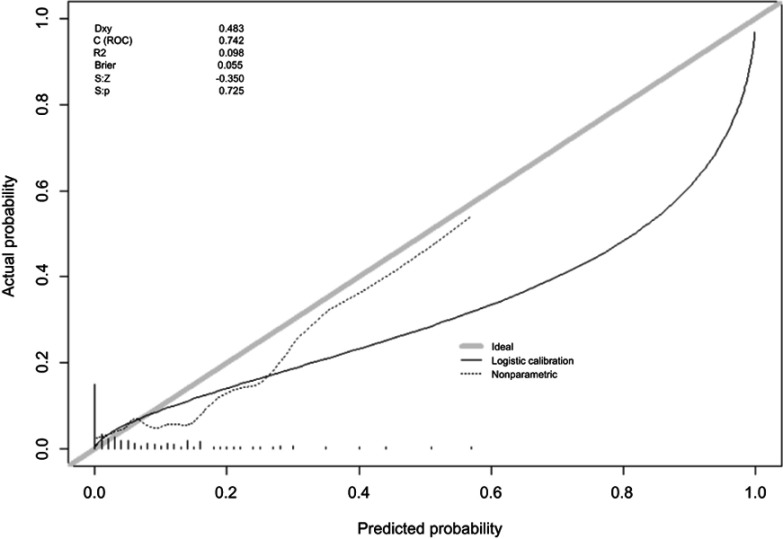

Construction and validation of nomograms

Based on multivariable model, a nomogram for the prediction of a higher risk of treatment failure (non-responding to treatment) was created based on SII, pre-treatment hemoglobin values and nodal status. Specifics regarding univariate and multivariate analyses are reported in Table S3. The graphical representation of the nomogram is shown in Figure 4. Probabilities predicted by the nomogram were tested against those observed in the validation set. The nomogram discriminative ability was satisfying with a C-index of 0.742 (0.596–0.951) (Figure S1). Brier score was 0.055 and the Spiegelhalter Z-test was not significant (p=0.726). Visual inspection of the calibration plot showed acceptable overlap between predicted and observed probabilities, even if there was a slight underestimation for patients at higher risk of nonresponse.

Table S3.

Results of univariate and multivariate logistic model for prediction of nonresponse

| Variable | Univariate model | Multivariate model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| SII | 3.03 | 2.24–3.84 | 2.99 | 2.04–3.94 |

| N+ vs N– | 13.73 | 11.64–15.82 | 5.88 | 3.37–8.40 |

| Pre-treatment Hb (g/dL) | 0.61 | 0.24–0.98 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Pre-treatment NLR | 1.24 | 1.01–1.47 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Pre-treatment PLR | 1.65 | 1.20–2.11 | n.s. | n.s. |

Abbreviations: SII, systemic index of inflammation; N, lymph node status; Hb, hemoglobin; NLR, neutrophils to lymphocyte ratio; n.s., not significant; PLR, platelets to lymphocyte ratio.

Figure 4.

Nomogram with predictors of response to chemoradiotherapy.

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; SII, systemic index of inflammation.

A calculator (ARC: Anal cancer Response Classifier) has also been developed and it is available for online consultation. The link is accessible in supplemental materials.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the correlation between baseline immune inflammation indicators and prognosis in patients with SCCA. We found that pre-treatment SII levels had a significant correlation to PFS, being the most important parameter for response prediction in this setting of patients.

Standard CT-RT for radical treatment in SCCA provides consistent results in terms of local control and survival. However, not all patients are suitable for definitive treatment and a subset of patients may have a dismal prognosis, with little or no response to CT-RT. Our analysis showed that objective clinical response is the most important predictor of long-term survival and cure. Patients who do not respond to treatment face a very poor prognosis; regardless of salvage strategies in the attempt to identify this subset of patients, we developed a nomogram to predict the absence of response in anal cancer undergoing CT-RT. Nomograms are useful tools for risk prediction and classification. Although several kinds of algorithms may be used for the same purpose, to date nomograms remain the most powerful and widely used tool to be applied in the clinics. One substantial advantage of nomograms is that they are easy to understand and used by professionals with a little statistical background. For example, a patient without metastasis in the lymphnode, hemoglobin pretreatment of 13 and SII of 12 would have a total of 48 points (metastasis in the lymphnode = 0 points; HB =18 points and SII = 30 points). This patient had 0.2% prediction of no response. Another patient with metastasis in the lymphnode, HB pretreatment of 13 and SII of 12 would have a total of 86 points (metastasis in the lymphnode = 38 points; HB = 18 points and SII = 30 points). This patient had a slightly higher probability of nonresponse (2%). Conversely, a patient with metastasis in the lymphnode, HB pretreatment of 13 and SII of 15 would have a total of 146 points (metastasis in the lymphnode = 38 points; HB = 18 points and SII = 90 points) and 38% prediction of no response. In our nomogram, SII showed the greatest accuracy in predicting response. An online available calculator (ARC: Anal cancer Response Classifier) has also been developed. The link is accessible in supplemental materials.

Inflammation is an intrinsic feature of cancer, contributing to its development and progression.29 SII represents the balance between protumor inflammatory pathway activation and antitumor immune function. A rise in SII can be determined by three conditions, ie, neutrophilia, lymphopenia and thrombocytosis, suggesting a high inflammatory status and an exhausted immune response in patients. For these reasons, we think that patients with higher SII had a worse clinical response to CT-RT. This could be explained by the recent results of Martin et al. and the ACT I trial that showed that higher peripheral leukocytosis is associated with poor outcome in patients treated with CT-RT. Moreover, Martin et al. demonstrated an inverse correlation between leukocytosis and intratumoral CD8+. Balermpas et al.30 also proved that high tumor HPV16 viral load, CD8+ and PD-L1 are associated with favorable prognosis in this setting of patients. Conversely, Zhao et al.31 and Govindarajan et al.32 highlighted the negative impact of the expression of PD-L1 on clinical outcome. These studies demonstrated a high level of PDL-1 expression. According to these data, a recent study proved an encouraging antitumor activity in patients with PD-L1-positive advanced anal carcinoma HPV+.33

Neutrophilia can prompt secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor, angiogenetic cytokine and therefore accelerate tumor development and seeding at distant organ sites.34,35 On the other hand, lymphopenia is associated with a more severe level of the disease36–38 and immune escape of tumor cells from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.39,40

In anal cancer patients, baseline leukocytosis (defined as leukocyte >10,000/ul) and neutrophilia (defined as neutrophil count >7,500/ul) were found to be significantly associated (p<0.01) to oncological outcomes [OS, PFS and disease-free survival (DFS)], independently of tumor and nodal stage at diagnosis.41 These 2 biomarkers were also externally validated as independent prognostic factors in the same group.42

This was also confirmed by the study by Banerjee et al. in which patients with leukocytosis (leucocyte >10.000/ul) and anemia (pre-treatment Hemoglobin level <12.5 g/dl) had poor DFS and OS.43 This is in line with our findings, where both SII (a measure that reflects leukocyte number) and anemia were found to be predictors of response to CT-RT, which is a reliable surrogate endpoint for survival.28

Several studies have shown that platelets induce circulating tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promote extravasation to metastatic sites.44 Circulating platelets actively signal to tumor cells, via TGFβ and NF-κB, to promote their malignant potential outside the primary microenvironment, inducing prometastatic phenotype.44

In this context, a rise in SII represents the lack of a correct balance of immune control in the tumor itself: this could explain the worse outcomes that we reported in this study.

Toh et al22 proved that pretreatment NLR could be a predictor of outcome in these patients, although our results showed that SII was a better predictor than NLR.

Based on our nomograms, for patients with higher risk of no response to CT-RT, CT-RT response should be evaluated before the 56th week, and biopsies should be performed more frequently for response monitoring. Furthermore, these patients should undergo treatment according to dose escalation protocols or boost with brachytherapy.

The main limitations to this work are its retrospective nature and a relatively short follow-up time. Although we considered many known prognostic factors (eg, gender and age), we cannot completely rule out the possibility of selection bias or bias from other confounders. It is also possible that a longer follow-up would have yielded different results. However, our findings are statistically significant and in line with previous publications on other cancer types. Another limitation are the different time points when complete response was assessed, as they varied across participating centers.

The literature is consistent in saying that systemic inflammation indexes are related to prognosis and response to treatment: our results confirmed SII as a strong and independent prognostic factor for both response and PFS, which could be helpful in identifying patients most likely not to benefit from CT-RT for whom other treatment strategies should be timely evaluated.45

In conclusion, the low cost and easy profile in terms of determination and reproducibility make SII a promising tool for prognostic assessment in this oncological setting.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Cristiano Verna and Veronica Zanoni for editing the manuscript.

Disclosure

Professor Mario Scartozzi reports personal fees and other from CELGENE, grants and personal fees from MERCK, and personal fees from AMGEN, Lilly, Bayer, and Servier, outside the submitted work. Professor Stefano Cascinu reports personal fees from Servier and Lilly and grants and personal fees from Eisai and Celgene, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Anal carcinoma. Version 2.2017. [Online 20April, 2017]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/anal_blocks.pdf.

- 2.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:270–280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frisch M, Glimelius B, van Den Brule AJ, et al. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grulich AE, Poynten IM, Machalek DA, Jin F, Templeton DJ, Hillman RJ. The epidemiology of anal cancer. Sex Health. 2012;9:504–508. doi: 10.1071/SH12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan DP, Compton CC, Mayer RJ. Carcinoma of the anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:792–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003163421107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B. Combeined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uronis HE, Bendell JC. Anal cancer: an overview. Oncologist. 2007;12:524–534. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gastr. Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, et al. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a Phase III randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2040–2049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullen JT, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Chang GJ, et al. Results of surgical salvage after failed chemoradiation therapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:478–483. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9221-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faivre C, Rougier P, Ducreux M, et al. 5-Fluorouracile and cisplatinum combination chemotherapy for metastatic squamous-cell anal cancer. Bull Cancer. 1999;86:861–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaiyesimi IA, Pazdur R. Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil as salvage therapy for recurrent metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Am J Clin Oncol. 1993;16:536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nozoe T, Matsumata T, Kitamura M, Sugimachi K. Significance of preoperative elevation of serum C-reactive protein as an indicator for prognosis in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1998;176:335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toiyama Y, Inoue Y, Saigusa S, et al. C-reactive protein as predictor of recurrence in patients with rectal cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:5065–5074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, et al. Prognostic significance of the preoperative serum C-reacrive protein level in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. Surg Today. 2015;45(3):315–321. doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-0909-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng JF, Chen S, Yang X. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is a useful prognostic indicator for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Medicine. 2017;96:1–6. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong X, Cui B, Wang M, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, based on platelet counts and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, is useful for predicting prognosis in small cell lung cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med 2015;236(4):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin D, Rödel F, Winkelmann R, Balermpas P, Rödel C, Fokas E. Peripheral leukocytosis is inversely correlated with intratumoral CD8+ T-cell infiltration and associated with worse outcome after chemoradiotherapy in anal cancer. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1225. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, Adams R, et al. Prognostic factors for recurrence and survival in anal cancer: generating hypotheses from the mature outcomes of the first United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research Anal Cancer Trial (ACT I). Cancer. 2013;119(4):748–755. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casadei Gardini A, Scarpi E, Faloppi L, et al. Immune inflammation indicators and implication for immune modulation strategies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib. Oncotarget. 2016;7(41):67142–67149. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruix J, Cheng A-L, Meinhardt G, Nakajima K, De Sanctis Y, Llovet J. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two Phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017;67(5):999–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toh E, Wilson J, Sebag-Montefiore D, Botterill I. Neutrophil:lymphocyteratio as a simple and novel biomarker for prediction of locoregionalrecurrence after chemoradiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(3):O90–O97. doi: 10.1111/codi.12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kachnic LA, Winter K, Myerson RJ, et al. RTOG 0529: a Phase 2 evaluation of dose-painted intensity modulated radiation therapy in combination with 5-fluorouracil and mytomycin C for the reduction of acute morbidity in carcinoma of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franco P, Arcadipane F, Ragona R, et al. Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) in the combined modality treatment of anal cancer patients. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:2015832. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arcadipane F, Franco P, Ceccarelli M, et al. Image-guided IMRT with simultaneous integrated boost as per RTOG 0529 for the treatment of anal cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2018;14:217–223. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoff CM. Importance of hemoglobin concentration and its modification for the outcome of head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:419–432. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.653438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roldan GB, Chan AK, Buckner M, et al. The prognostic value of hemoglobin in patients with anal cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1127–1134. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181d964c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franco P, Montagnani F, Arcadipane F, et al. The prognostic role of hemoglobin levels in patients undergoing concurrent chemo-radiation for anal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-1035-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment eff ectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e493–e503. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balermpas P, Martin D, Wieland U, et al. Human papilloma virus load and PD-1/PD-L1, CD8 and FOXP3 in anal cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy: rationale for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(3):e1288331. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1288331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Y-J, Sun W-P, Peng J-H, et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression correlates with diminished CD8+ T cell infiltration and predicts poor prognosis in anal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1–11. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S153965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Govindarajan R, Gujja S, Siegel ER, et al. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in anal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(7):638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ott PA, Piha-Paul SA, Munster P, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab in patients with recurrent carcinoma of the anal canal. Annal Oncol. 2017;28:1036–1041. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pm H. Pathobiology of the neutrophil-intestinal epithelial cell interaction: role in carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5790–5800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nind AP, Nairn RC, Rolland JM, Guli EP, Hughes ES. Lymphocyte anergy in patients with carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1973;28:108–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calman KC. Tumour immunology and the gut. Gut. 1975;16:490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Giorgi U, Mego M, Scarpi E, et al. Relationship between lymphocytopenia and circulating tumor cells as prognostic factors for overall survival in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, et al. Lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer is associated with longer survival, indepent of lymph node count, microsatellite instability and CpG island methylator phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6412–6420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waldner M, Schimanski CC, Neurath MF. Colon cancer and the immune system: the role of tumor invading T cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7233–7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ropponen KM, Eskelinen MJ, Lipponen PK, Alhava E, Kosma VM. Prognostic value of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 1997;182:318–324. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schernberg A, Escande A, Rivin Del CE, et al. Leukocytosis and neutrophilia predicts outcome in anal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2017;122:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schernberg A, Huguet F, Moureau-Zabotto L, et al. External validation of leukocytosis and neutrophilia as a prognostic marker in anal carcinoma treated with definitve chemoradiation. Radiother Oncol. 2017;124:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banerjee R, Roxin G, Eliasziw M, et al. The prognostic significance of pretreatment leukocytosis in patients with anal cancer treated with radical chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:21036–21042. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31829ab0d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:576–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franco P, Mistrangelo M, Arcadipane F, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost combined with concurrent chemotherapy for the treatment of anal cancer patients: 4-year results of a consecutive case series. Cancer Invest. 2015;33(6):259–266. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2015.1028586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.