Abstract

Microglia are CNS-resident macrophages that scavenge debris and regulate immune responses. Proliferation and development of macrophages, including microglia, requires Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R), a gene previously associated with a dominant adult-onset neurological condition (adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia). Here, we report two unrelated individuals with homozygous CSF1R mutations whose presentation was distinct from ALSP. Post-mortem examination of an individual with a homozygous splice mutation (c.1754−1G>C) demonstrated several structural brain anomalies, including agenesis of corpus callosum. Immunostaining demonstrated almost complete absence of microglia within this brain, suggesting that it developed in the absence of microglia. The second individual had a homozygous missense mutation (c.1929C>A [p.His643Gln]) and presented with developmental delay and epilepsy in childhood. We analyzed a zebrafish model (csf1rDM) lacking Csf1r function and found that their brains also lacked microglia and had reduced levels of CUX1, a neuronal transcription factor. CUX1+ neurons were also reduced in sections of homozygous CSF1R mutant human brain, identifying an evolutionarily conserved role for CSF1R signaling in production or maintenance of CUX1+ neurons. Since a large fraction of CUX1+ neurons project callosal axons, we speculate that microglia deficiency may contribute to agenesis of the corpus callosum via reduction in CUX1+ neurons. Our results suggest that CSF1R is required for human brain development and establish the csf1rDM fish as a model for microgliopathies. In addition, our results exemplify an under-recognized form of phenotypic expansion, in which genes associated with well-recognized, dominant conditions produce different phenotypes when biallelically mutated.

Keywords: CSF1R, microglia, neuropathology, leukoencephalopathy, axonal spheroids, CUX1, agenesis corpus callosum, recessive, osteopetrosis, zebrafish

Introduction

Microglia are tissue-resident macrophages of the brain that scavenge cellular debris and regulate CNS immune responses. Although research has focused on their role in age-related neurodegenerative disorders, more recently roles for microglia in normal nervous system development, both in the presence and absence of environmental stressors (prenatal inflammation, low birth weights), have emerged. For example, microglia remodel neuronal circuits, engulf neuronal progenitors, prune synapses, and control axonal projections, and mice engineered to develop without microglia show structural brain abnormalities, including ventriculomegaly and agenesis of corpus callosum (ACC).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Microglia originate from macrophages within the embryonic yolk sac, and their development requires signaling through the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R).7, 8, 9 This receptor tyrosine kinase is expressed in macrophages and is thought to regulate their proliferation and development.10 In humans, heterozygous mutations in CSF1R (MIM: 164770) cause adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP [MIM: 221820]), a fatal neurologic disorder that presents with progressive cognitive and motor impairment and seizures in the fourth to fifth decade of life.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Imaging shows diffuse signal changes and atrophy of the white matter, suggesting primary white matter disease.17 ALSP is a newer diagnostic term that includes both hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS) and pigmented orthochromatic leukodystrophy (POLD), now recognized as a single clinicopathological entity.13 ALSP is a prototypical “microgliopathy” because genetics point to microglial dysfunction as the primary disease mechanism.13, 18, 19

Here, we describe two individuals with homozygous CSF1R mutations who presented with pediatric phenotypes distinct from ALSP. One individual developed severe developmental regression and epilepsy at 12 years of age and was found to have severe leukodystrophy and periventricular calcifications at age 24. The other presented prenatally with structural brain malformations, including agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC), and died before 1 year of age. Post-mortem analysis identified a complete absence of microglia within the brain, suggesting that it developed in the absence of microglia. To further investigate how absence of CSF1R signaling affects affect brain development, we generated CSF1R-deficient zebrafish.20 These CSF1R-deficient fish (csf1rDM) also lacked microglia. Proteomics analysis (mass spectrometry) in csf1rDM fish brain, in conjunction with immunostaining of human CSF1R mutant cortex, identified reduced levels of the neuronal transcription factor CUX1. Since a large fraction of CUX1+ neurons project axons into the corpus callosum,21 we speculate that a deficiency of microglia numbers or function leads to decreased CUX1+ cells, possibly via reduced trophic support, contributing to an agenesis of corpus callosum phenotype. These results establish the csf1rDM fish as a model for microgliopathy and provide a starting point for unraveling the role of microglia in brain development.

Material and Methods

Study Participants

Informed consent was obtained from subjects prior to enrollment in the study. Approval for research on human subjects was obtained from IRBs at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Exome Sequencing

Exome sequencing (ES) was performed as part of clinical care on peripheral blood samples from probands and both biological parents, using the Agilent Clinical Research Exome kit. Targeted regions were sequenced simultaneously on an Illumina HiSeq with 100 bp paired end reads. Bidirectional sequence was assembled and aligned to human reference genome build GRCh37/UCSC hg19. Data were analyzed for sequence variants as previously described.22, 23

Zebrafish Maintenance

For the experiments WT (TL), csf1rDM, and csf1ra−/−;b+/− mutants were used. The csf1r mutants were described in detail elsewhere.20 Briefly, csf1raj4e1/j4e1 mutants have a p.Val614Met substitution in the first kinase domain.24 The csf1rb deletion mutant was created by TALEN-mediated genome editing.25 The TALEN arms targeted exon 3 of the csf1rb gene, resulting in a 4 bp deletion and premature stop codon. The zebrafish were kept at 28°C and fed brine shrimp twice a day. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of the Erasmus MC, Rotterdam.

Zebrafish Histology and Immunostaining Procedures

L-plastin antibody and neutral red staining were performed as described previously.26, 27, 28

Human Cortical Sectioning and CUX1 Immunohistochemistry and Quantification

As a control for CUX1 immunohistochemistry in cerebral cortex, sections were taken from another autopsy case with similar age, sex, and tissue processing. This male individual with 22q11 deletion syndrome died of aseptic shock at 7 months and 2 weeks of age. The post-mortem interval was 4 h. Sections of cerebral cortex from three different brain lobes were obtained, sectioned identically as described for other histological studies, deparaffinized, processed for CUX1 immunofluorescence using anti-CUX1 antibodies (ab54583, Abcam), and counterstained with DAPI, as described.29 Fluorescence images were collected using the same exposure settings for all images. The number of CUX1+ cells was counted within segments of cerebral cortex extending from pia to white matter within a defined area, as described previously.30 Using ImageJ, the areas of the rectangles were measured. Finally, the density of CUX1+ cells was calculated by dividing cell counts by area. Cell densities were compared statistically by t test using each cortical sample as a separate count (n = 3), with significance defined as p < 0.05.

Alizarin Red Staining

Size-matched adult zebrafish were eviscerated and incubated in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight. Next, they were rinsed in 80% EtOH for 1 h, after which they were washed in 70% MeOH for 5 min and incubated in 70% MeOH at 4°C overnight. The fish were then washed in 50% MeOH for 5 min and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min twice. Bleach (0.8% KOH, 0.9% H2O2, 0.2% Triton X-100) was used to remove the pigment. Bleaching was followed by two 5 min wash steps in 0.2% Triton X-100. The fish were neutralized in concentrated borax for 15 min. Next, the fish were digested with 0.1% Trypsin, 0.6% Borax, and 0.08% Triton X-100 for 4 h). Then the fish were incubated in an alizarin red solution (0.05% Alizarin red, 25% glycerol, 100 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) at room temperature overnight. The fish were incubated in 0.5% KOH in 50% glycerol overnight, followed by incubation in 0.3% KOH in 70% glycerol for several weeks until sufficient staining was achieved as desired.

Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Analysis

Protein lysates were obtained from dissected brains from 6- to 8-month-old zebrafish (3 brains per sample, samples in triplicate) with the following genotypes: csf1rDM, csf1ra−/−;b+/−, and csf1ra+/+;b+/+ (a.k.a. wild-type littermates). After endoproteinase and tryptic digestions, peptides were labeled with 10-plex tandem mass tag (TMT) reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subjected to orthogonal high-pH and reverse phase fractionation. Mass spectra were acquired on an Oribtrap Lumos (Thermo) coupled to an EASY-nLC 1200 system (Thermo), and peak lists were automatically created using the Proteome Discoverer 2.1 (Thermo) software. For further analysis, we used the R packages vsn and limma.31, 32 For complete proteomics methods, see Supplemental Subjects and Methods.

Results

Clinical Findings and Exome Analysis

Trio-based exome sequencing (ES) identified homozygous variants (GenBank: NM_005211.3; c.1754−1G>C) in the gene CSF1R (Figure 1) in a male infant (family CSF1R_01, individual II-1 in Figure 1) with multiple congenital anomalies. No other pathogenic variants were identified. Both parents and two grandparents carried this variant in the heterozygous state. All four of these individuals denied any neurologic symptoms; however, they were all less than 40 years, the average age of symptom onset for ALSP. This infant presented with prenatal structural brain abnormalities, including ACC, ventriculomegaly, and pontocerebellar hypoplasia. These abnormalities were confirmed by postnatal imaging (MRI and CT), which also demonstrated periventricular calcifications and Dandy-Walker malformation (Figures 2A–2D). There was known shared ancestry, and a chromosomal microarray found 3.1% of the autosomal genome to be homozygous. There was hypocalcemia requiring intravenous calcium supplementation, and X-rays showed generalized increased bone density (osteopetrosis) and irregular metaphyses (Figures 2M–2O). His clinical course was complicated by respiratory failure, oromotor discoordination requiring gastrostomy feeding, and intractable epilepsy (Table 1). He died at 10 months of age from streptococcal bacteremia, and a brain-only autopsy was performed (see below). A more complete clinical description can be found in Supplemental Note.

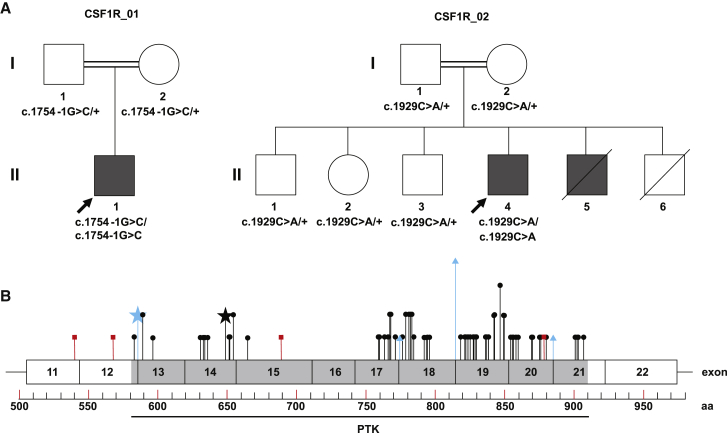

Figure 1.

Pedigrees and Distribution of CSF1R Mutations

(A) Pedigrees of family CSF1R_01 and CSF1R_02 shown, with genotypes indicated. CSF1R sequencing was not performed for II-5, but this individual is shaded to reflect his leukodystrophy and periventricular calcifications.

(B) Exons 11-22 of the CSF1R protein (GenBank: NP_005202.2) are shown. No mutations have been reported in the five immunoglobin (Ig) domains and transmembrane domain upstream of exon 11, which are not shown. The intracellular protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) domain is indicated. The 64 previously reported pathogenic variants causative for ALSP are shown (truncating variants in red squares, missense and in-frame indel variants in black circles, splice variants in blue triangles). The splice site variant identified in family CSF1R_01 (GenBank: NM_005211.3; c.1754−1G>C) is indicated by the blue star. The missense variant identified in family CSF1R_02 (GenBank: NM_005211.3; c.1929C>A [p.His643Gln]) is indicated by the black star. Amino acids containing multiple variants are specified by proportionally taller lines. A complete list of reported CSF1R variants is in Table S1.

Figure 2.

Brain and Bone Abnormalities in CSF1R Deficiency

Shown are MRI images of individual II-1 (at age 2 days) from family CSF1R_01 (A–F) and MRI images of individual II-4 (at age 25 years) from family CSF1R_02 (G–L). (A)–(E) are T1 weighted images; (F)–(H) are T2 weighted; (I) and (K) are T1 FLAIR images; and (J) and (L) are T2 FLAIR images.

(A) Midsagittal section shows agenesis of corpus callosum (asterisk), pontocerebellar hypoplasia (arrowhead), and small and upwardly rotated cerebellar vermis (arrow) with large posterior fossa cyst (“X”).

(B) Parasagittal section shows diffuse calcifications along lateral ventricles (arrowhead) and small cerebellum and posterior fossa cyst (arrow). Note calcifications were confirmed on CT imaging (not shown) and gross pathology (Figure S4).

(C) Horizontal section shows periventricular calcification around 3rd and lateral ventricles (arrow and asterisks, respectively).

(D) Coronal section showing ventriculomegaly (asterisks), hypoplasia of cerebellar hemispheres and large posterior fossa cyst (arrow).

(E and F) Periventricular white matter signal abnormality, with areas of T2 hyperintensity (arrow in F) with corresponding T1 hypointensity (arrow in E).

(G) Midsagittal section showing cerebellar vermis hypoplasia/atrophy and hypoplasia of corpus callosum (arrow).

(H) Parasagittal section showing periventricular T2 hyperintensities (arrow).

(I–L) Axial T1 FLAIR (I and K) and corresponding T2 FLAIR images (J and L) showing frontal lobe predominant periventricular white matter signal abnormality, with areas of T2/FLAIR hyperintensity with corresponding T1 hypointensity (arrows).

(M–O) X-rays of individual II-1 from family CSF1R_01 showing generalized increased bone density and metaphyseal dysplasia (arrows).

Table 1.

Phenotypes of Six Individuals with Confirmed or Possible Biallelic CSF1R Mutations

| CSF1R_01: II-1 | CSF1R_02: II-4 | Monies et al.33sib1 | Monies et al.33sib2 | Rees et al.34sib1 | Rees et al.34sib2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF1R mutation (NM_005211.3) | c.1754−1G>C | c.1929C>A (p.His643Gln) | c.1620T>A (p.Tyr540∗)a | c.1620T>A (p.Tyr540∗)a | not sequenced | not sequenced |

| Symptom onset | prenatal | 12 y | perinatal | perinatal | perinatal | perinatal |

| Age at last evaluation | 10 m (death) | 24 y (living) | perinatal (death) | perinatal (death) | 9 m (death) | 1 m (death) |

| Consanguinity | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| More than 1 affected family member | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ethnicity | Native American | Arab | Arab | Arab | unk | unk |

| Gender | M | M | unk | unk | F | M |

| Developmental delay (onset) | + (3 m) | − (regression 12 y) | unk | unk | unk | unk |

| Macrocephaly | present (+5 SD) | absent | unk | unk | absent (10%) | “tower shaped” |

| Infantile hypotonia | + | unk | unk | unk | unk | unk |

| Spasticity | mild | + (spastic quad.) | unk | unk | unk | unk |

| Hyperreflexia | − | + | unk | unk | unk | unk |

| Epilepsy (onset) | yes (8 m) | yes (12 y) | unk | unk | unk | unk |

| Agenesis of corpus callosum | + | + (hypoplastic) | + | + | + | + |

| Ventriculomegaly | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Periventricular Calcification | + | + | + | + | unk | unk |

| Cerebellar hypoplasia/atrophy | + | + | + | + | unk | unk |

| Heterotopia | + | − | unk | unk | unk | unk |

| Leukodystrophy | + | + | unk | unk | + | unk |

| Mega Cisterna Magna | + | + | + | + | unk | unk |

| Upwardly rotated cerebellar vermis | + | − | + | + | unk | unk |

| Axonal spheroids | + | unk | unk | unk | + | unk |

| Osteopetrosis | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Hypocalcemia | + | − | + | + | + | unk |

Spastic quad., spastic quadriplegia; CSP, cavum septum pellucidum; unk, unknown because not reported in publication

Mutation not confirmed but likely based on “linkage by exclusion”

The c.1754−1G>C variant disrupts a splice acceptor site and is predicted to cause exon 13 skipping and production of an in-frame protein product (p.Gly585_Lys619delinsAla). Amino acids 585–619 are within the tyrosine kinase domain, like all but two of the previously reported pathogenic variants in this gene (Figure 1 and Table S1). We classified this variant as likely pathogenic using American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMGG) guidelines: it is absent from the ExAC and gnomAD population databases (PM2), predicted to change the length of the protein (PM4), and is located in a functional domain where pathogenic mutations have previously been reported (PM1).35 In addition, a de novo heterozygous variant at the −2 position of the same splice acceptor site (c.1754−2A>G) has been previously reported as pathogenic in ALSP.14 The phenotype of individual CSF1R_01:II-1 was distinct from ALSP, suggesting that biallelic variants in this gene cause a more severe, prenatal-onset disorder. Additional support of pathogenicity comes from an independent report of siblings with a very similar phenotype whose parents both carried a heterozygous truncating mutation in CSF1R (c.1620T>A [p.Tyr540∗]).33 However, DNA was not available from the affected siblings for confirmation in this report.

To increase our confidence that homozygous mutations in CSF1R cause a phenotype distinct from ALSP, we used Genematcher to find an additional family (CSF1R_02) with homozygous CSF1R mutations (GenBank: NM_005211.3; c.1929C>A [p.His643Gln]), identified by trio exome sequencing. No other pathogenic variants were identified. This 24-year-old man (individual II-4 in Figure 1) presented with epilepsy and developmental regression at age 12 years (Table 1). Prior to this age he was developmentally normal. MRI at age 24 years showed ventriculomegaly, severe leukodystrophy, cerebellar vermis atrophy, cavum septum pellucidum, and mega cisterna magna (Figures 2E and 2F). Since the age of 12 he steadily lost developmental milestones and at the present time he is unable to walk, speak, read, or feed himself. His seizures were classified as generalized tonic-clonic and did not respond to multiple anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs); however, he is currently seizure free and has not been taking AEDs for several years. His family history was notable for parental consanguinity and a brother (II-5) with a similar phenotype, who died at age 21 (Figure 1). This individual (II-5) also had leukodystrophy, developmental delay, and epilepsy. Another sibling (II-6) died at age 4, but imaging and phenotypic details of this individual were not available. DNA was not available from either of these deceased individuals, but both parents (I-1 and I-2) and all three unaffected siblings (II-1, II-2, and II-3) were heterozygous for this variant (Figure S1). X-rays of individual II-4 at age 24 showed no evidence of osteopetrosis and there was no known history of hypocalcemia (not shown). There was no history of adult-onset neurologic disorder in the parents (ages 50 and 56 years) or the siblings (ages 18–34).

Using ACMGG guidelines,35 we classified this variant as likely pathogenic as follows: (1) it is absent from ExAC and gnomaAD, as well as the Greater Middle East Variome and Iranome population databases (PM2); (2) it is located within the kinase domain, where the majority of pathogenic variation in this gene has been reported (PM1); (3) multiple in silico tools (PolyPhen, SIFT) predict this variant to be damaging (PP3); and (4) segregation data are consistent (PP1). Together, our data suggest that homozygous CSF1R mutations cause a severe, pediatric-onset neurodevelopmental condition that includes neuroimaging features that overlap with and are distinct from the adult-onset condition caused by heterozygous CSF1R mutations.

Autopsy Findings

We were able to perform brain-only autopsy on the individual from family CSF1R_01 (II-1 in Figure 1). Gross examination identified ACC, ventriculomegaly, periventricular calcification, and an expanded 4th ventricle with upward rotation of the cerebellar vermis (Dandy-Walker malformation), as detected by MRI (Figure S4). Periventricular heterotopias of the lateral and 4th ventricles not recognized by MRI were detected at autopsy (Figure S4). Histologic examination identified features also seen in ALSP, including scattered foci of white matter atrophy, gliosis, and dystrophic calcification, as well as abundant axonal spheroids in most white matter tracts, including corticospinal, dorsal column, and intracortical pathways (Figures 3A–3E). In contrast to ALSP, where microglia numbers are present but locally depleted,20 we were unable to identify any microglia in the brain parenchyma (Figures 3F–3Q). We did identify rare CD68- and Iba1-positive cells, but these were primarily clustered around small blood vessels and exhibited round rather than normal ramified morphology (Figures 3I–3T; complete brain autopsy report found in Supplemental Data). These data support our conclusion that the homozygous c.1754−2A>G CSF1R mutations led to a brain that developed in the absence of normal numbers of microglia with numerous structural brain malformations.

Figure 3.

Microscopic Brain Abnormalities in CSF1R Deficiency

Sections from individual II-1 from family CSF1R_01 (A–E, I–K, O–Q); sections from control brain (F–H, L–N).

(A and B) Adjacent sections through right frontal cortex, stained with H&E (A) and neurofilament protein immunohistochemistry (B). The white matter contained a focus of calcification, necrosis, and axon loss (arrowheads).

(C) Deep cerebellar white matter contained disorganized heterotopia (arrowheads) beneath the cerebellar cortex, and multiple periventricular foci of calcification and severe gliosis (arrows). Stained with H&E.

(D and E) Neurofilament immunohistochemistry demonstrated axonal spheroids in right frontal white matter. Similar axonal spheroids seen in anterior and lateral corticospinal tracts and nucleus cuneatus (not shown).

(F–H) Iba1 immunohistochemistry in control white matter labeled numerous microglia with long, ramified processes insinuating through brain tissue. (G) and (H) are enlarged 2-fold relative to (F).

(I–K) Iba1 immunohistochemistry in white matter from individual II-1 revealed decreased numbers of microglia, with abnormal rounded morphology, located mainly in perivascular spaces. (J) and (K) are enlarged 2-fold relative to (I).

(L–N) CD68 immunohistochemistry in control white matter. (M) and (N) are enlarged 2-fold relative to (L).

(O–Q) CD68 immunohistochemistry in white matter from individual II-1. Black arrows indicate blood vessels with no CD68-positive cells; the red arrow (O, enlarged in Q) indicates a rare perivascular CD68-positive cell. (P) and (Q) are enlarged 2-fold relative to (O).

Scale bars: (A) 1 cm for (A) and (B); (C) 1 cm for (C) only; (D) 20 μm for (D)–(E); 40 μm for (F), (L), (I), (O); 20 μm for (G), (H), (J), (K), (M), (N), (P), (Q).

We were unable to directly evaluate skeletal pathology in this individual but hypothesize that a reduction in CSF1R signaling and developmental failure of yolk-sac-derived tissue macrophages led to reduced numbers or function of osteoclasts. The presence of hypocalcemia and osteopetrosis is consistent with osteoclast failure (Table 1, Figures 2M–2O).

Model Organism Studies

To further explore mechanisms of brain development in the absence of microglia, we used recently developed zebrafish mutants.20 Zebrafish have two CSF1R homologs, csf1ra and csf1rb. We engineered a 4 bp frameshifting deletion in exon 3 of csf1rb that results in a premature stop and crossed these fish to a previously generated missense mutation in csf1ra.24 Microglia were not present in the brains of csf1ra/csf1rb double homozygous mutant (csf1rDM) fish at 5 days after fertilization (Figures 4A–4C). Similar to human CSF1R homozygous brain, we identified a few cells positive for zebrafish microglia marker L-plastin, which also lacked ramifications and were rounded (Figure 4C). To determine whether csf1rDM fish also showed evidence of osteopetrosis, similar to CSF1R_01:II-1, we examined vertebral arches (Figure 4D). Vertebral arches that contain the spinal cord (neural) and dorsal aorta (hemal) were smaller in csf1rDM fish compared to controls, as previously reported in osteopetrotic zebrafish mutants.36 Therefore, csf1rdm fish display both deficiency in brain microglia as well as osteopetrosis, recapitulating some of the bone and brain phenotypes seen in the individual (CSF1R_01:II-1) with homozygous c.1754−2A>G CSF1R mutations.

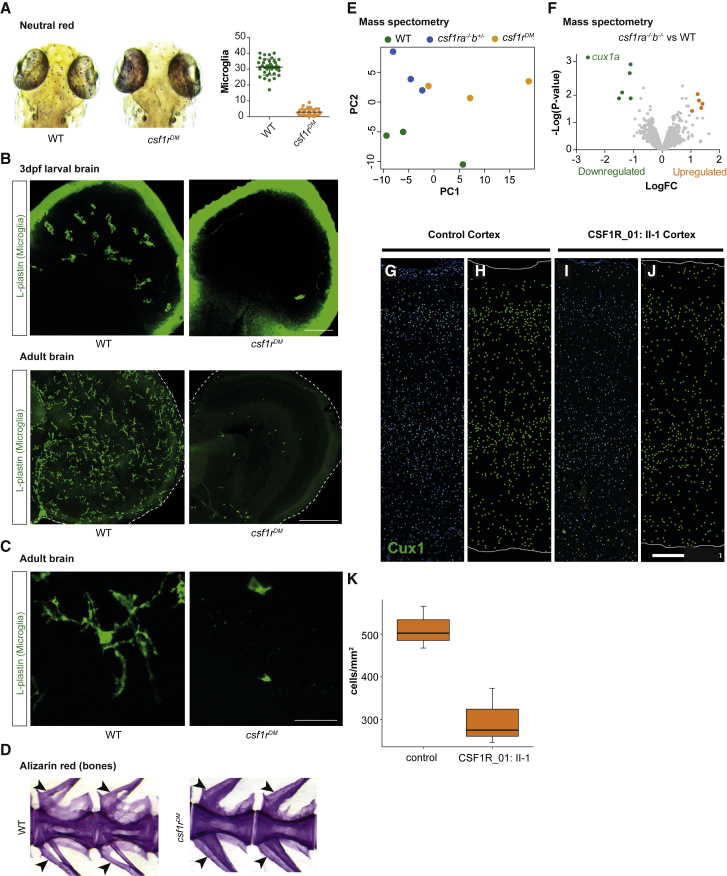

Figure 4.

Analysis of csf1rDM Zebrafish and CSF1R-Deficient Human Cortex

(A) Neutral red staining and quantification of microglia in zebrafish larvae (5 days after fertilization).

(B) Microglia immunostaining (L-plastin) in larval brains and adult brain sections of control and csf1rDM zebrafish.

(C) Microglia morphology in adult control and csf1rDM zebrafish (L-plastin immunostaining).

(D) Alizarin red staining of vertebrae and arches of adult control and csf1rDM zebrafish (size-matched, age 6–8 months) Neural arch (upper arrow) and hemal arch (lower arrow) indicated (E).

Principal component analysis (PCA) of mass spectrometry data of WT, csf1ra−/−; b+/−, and csf1rDM adult zebrafish brains. Csf1ra−/−; b+/− also have reduced microglia numbers.

(F) Volcano plot showing differentially regulated proteins in csf1rDM mutant brains as colored dots (FDR < 0.05, LogFC > |1|). Volcano plot of csf1ra−/−; b+/− versus control brain is included as Figure S2.

(G–K) CUX1+ cells were reduced in the cerebral cortex of CSF1R_01. CUX1 immunofluorescence (green) in control (G, H) and CSF1R-deficient (I, J) lateral temporal neocortex. The images with DAPI (blue) counterstain are shown in (G) and (I) and corresponding CUX1+ cell plots in (H) and (J).

(K) The density of CUX1+ cells was reduced in the cortex from three different areas of individual II-1, family CSF1R_01. Cortical regions in this analysis included left medial parietal, left lateral parietal, and left lateral temporal cortex (control) and left lateral temporal, right dorsolateral frontal, and right medial occipital cortex (CSF1R_01). Whiskers indicate 95% confidence interval, and difference between CSF1R_01:II-1 and control CUX1+ cell density was statistically significant (p < 0.05, one-sided t test, and p = 0.05, one-sided exact Wilcoxon rank sums test).

Next, we performed proteomic analysis of csf1rDM brains to explore underlying pathogenic mechanisms in human CSF1R mutant brains. Principal component analysis showed that the samples of the same genotype clustered together (Figure 4E), indicating consistent changes in protein levels among groups. The most highly downregulated protein was Cux1a (Figure 4F and see Table S2 for proteomic dataset), the zebrafish homolog of CUX1. CUX1 is a transcription factor present in subsets of neurons in all cortical layers and is required for the formation of layer II/III callosal projections.21 We were intrigued by this finding, as it suggested a mechanism for the absence of corpus callosum seen in individual CSF1R_01:II-1 that we could test by immunostaining cortical sections.

CUX1 Cortical Immunohistochemistry

Based on the zebrafish results, we hypothesized that CUX1+ neurons would also be decreased in CSF1R homozygous human brain. Sections of cerebral cortex from three different brain lobes from individual II-1 in family CSF1R_01 were processed and compared with sections from another age- and sex-matched autopsy case subject. The overall CUX1 laminar pattern was preserved, but immunoreactivity and density of CUX1+ cells were reduced (Figures 4G–4J). Our data, together with the observation that CUX1 is also downregulated in CSF1R-deficient mice,37 suggest an evolutionarily conserved role for CSF1R signaling in production or maintenance of CUX1+ neurons. We speculate that the decrease in the number of CUX1+ cells may have contributed to the ACC phenotype, as neurons from layers II-III contribute heavily to the corpus callosum.

Discussion

We report a detailed neuropathologic description of a human brain containing almost no microglia. Although scarce expression of CSF1R in neurons has recently been reported,37, 38 we believe the structural brain abnormalities are likely secondary to absence of myeloid cells, particularly microglia. Several observations support this claim. Brains of mice with neural lineage-specific deletion of Csf1r (Nestin-cre/+;Csf1rfl/fl) do not exhibit ventriculomegaly, olfactory bulb atrophy, or ACC, all of which are seen in complete Csf1r-null mice.2, 37 Neonatal microglia have recently been shown to contribute to normal myelinogenesis in the developing mouse brain by secretion of trophic factors, including IGF1,3, 6 and oligodendrocyte differentiation from neuronal precursor cells (NPCs) is enhanced by soluble CSF1 ligand only in the presence of microglia in culture.37, 39 Microglia have also been reported to influence axonal outgrowth and positioning/migration of interneurons.5 In addition, a very recent study demonstrated that transplanted bone-marrow-derived cells could rescue the phenotypes of Csf1r-null mice.40 Although a minor microglia-independent role for CSF1R cannot be completely ruled out,39 these data suggest that the major neurodevelopmental defects caused by loss of CSF1R signaling are due to a lack of microglia. Although we do not precisely know how lack of microglia leads to the brain malformations seen in CSF1R_01 and _02, we speculate that their absence disrupts oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelinogenesis, as well as migration of interneurons, that could directly and indirectly lead to the widespread white matter abnormalities and heterotopias seen in these individuals. Further research is needed to address these questions.

More than 60 mutations in CSF1R have been reported in individuals with ALSP, the majority of which are missense or in-frame indels within the tyrosine kinase domain (Figure 1, Table S1). It has been suggested that these mutations produce disease via a dominant-negative mechanism, in which kinase-deficient CSF1R molecules dimerize with wild-type molecules, inactivating them.14, 41 Haploinsufficiency has also been proposed as a disease mechanism, with the adult onset of ALSP being caused by a steady decrease in CSF1R levels, until it reaches a critical level.37, 42, 43 Our results provide genetic support that these mutations result in decreased CSF1R activity, possibly via both haploinsufficient and dominant-negative mechanisms, depending on the mutation. Additional support for a loss-of-function disease mechanism comes from individuals with polycystic lipomembranous osteodysplasia with sclerosing leukoencephalopathy (PLOSL, a.k.a. Nasu-Hakola disease). Individuals with PLOSL develop progressive dementia and cognitive decline in their 4th decade of life, similar to ALSP; however, they also develop bony symptoms (bone cysts and pathological fractures) around the same time.18, 44, 45, 46 PLOSL is an autosomal-recessive disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in components of the TREM2-TYROBP signaling complex, which interacts with CSF1R signaling, regulates osteoclast function, and is also present in microglia.47, 48, 49 The brain and bone features seen in CSF1R_01:II-1 overlap somewhat with pathology observed in PLOSL, although with much earlier symptom onset. Together the evidence supports a loss-of-function mechanism for CSF1R mutations, both in ALSP and in individuals with homozygous CSF1R mutations.

There are at least two previous reports of individuals with similar features. In 1995, Rees et al. described two siblings with “infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy and osteopetrosis,” and, with great foresight, noted similarity to the spontaneously arising osteopetrosis mouse, now known to be due to mutations in colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF1), the CSF1R ligand.34 More recently, Monies et al. described two siblings with brain malformations and osteopetrosis, whose parents both carried the same heterozygous truncating CSF1R mutation, but DNA was unavailable from the siblings to confirm that they were both homozygous and no pathologic data was available.33 We summarized key phenotypic features of individuals with confirmed homozygous mutations (individual II-1 from family CSF1R_01 and individual II-4 from family CSF1R_02), likely homozygous mutations (Monies et al.33 sibs 1 and 2), and unsequenced individuals (Rees et al.34 sibs 1 and 2) in Table 1. Although the size of this cohort is insufficient to know the full phenotypic spectrum, agenesis of corpus callosum, periventricular calcifications, ventriculomegaly, osteopetrosis, and hypocalcemia were seen in the majority, and axonal spheroids were seen in all individuals who underwent neuropathological examination.

Both individuals reported here had pediatric onset of disease, significantly earlier than been reported for ALSP. However, the phenotype of the individual from family CSF1R_01 (II-1) was significantly more severe than the individual from family CSF1R_02 (II-4), who remains alive at 24 years of age, and whose brain MRI findings overlap with ALSP.50 We speculate that the p.His643Gln single amino acid substitution is hypomorphic and results in relatively more CSF1R protein function than the exon 13 splice acceptor mutation (c.1754−1G>C) seen in CSF1R_01. Consistent with this hypothesis is the fact that the siblings reported by Monies et al.,33 who likely had a null mutation (c.1620T>A [p.Tyr540∗]), demonstrated a perinatal lethal phenotype. Further studies of the impact of these mutations on CSF1R function are needed.

Several features of CSF1R_01:II-1’s presentation, namely thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, intracranial calcifications, white matter loss, and failing the newborn hearing screen, are reminiscent of congenital infection. However, this individual presented with significant macrocephaly (+5 SD), whereas newborns with congenital infections are typically microcephalic. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome (AGS) and the microcephaly-intracranial calcification syndrome (MICS, also known as pseudo-TORCH) also have overlapping presentations. Lumbar puncture was never performed in this individual, so we could not measure CSF cell counts or interferon-alpha levels. At the present we can only speculate as to the mechanism of the inflammatory-like phenotype within the brain in the absence of microglia, the primary immune cells of the brain. Microglia, like other macrophages, have immune-regulatory roles as well, and it is possible that the lack of microglia leads to a failure to suppress immune responses. Alternatively, astrocytes have been shown to produce interferon-alpha, suggesting that cells other than microglia could also drive inflammation.51

Significantly, there was no family history of adult-onset neurodegenerative symptoms in either of the families we report, despite numerous individuals carrying heterozygous CSF1R mutations. Possible explanations include the age-related onset of symptoms, incomplete penetrance, or less deleterious variants in parents of children with pediatric-onset disease. This is similar to individuals with biallelic mutations in components of DNA mismatch repair proteins, who typically lack a family history of Lynch syndrome.52 The absence of a family history of ALSP cannot be used to rule out a possible diagnosis of biallelic CSF1R deficiency.

The zebrafish csf1rDM model recapitulates both the bone and specific brain features of these disorders, making it an excellent new model with which to study microgliopathies and the consequences of microglia absence. As a demonstration of how this model can lead to new insights, we identified Cux1a as a protein whose levels were significantly decreased in csf1rDM fish. We then demonstrated that there is also a decrease in the density of CUX1+ neurons in human CSF1R brain sections. Further studies of csf1r-deficient zebrafish brain are needed to identify the precise cellular consequences of a lack of Csf1r signaling/depletion of microglia. Although our hypothesis—that a reduction in density of CUX1+ layer II/III neurons contributes to the ACC phenotype—remains speculative, it demonstrates the translational capacity of our new zebrafish microgliopathy model.

Lastly, our study exemplifies an under-recognized type of phenotypic expansion, in which genes associated with well-recognized, dominant phenotypes can produce different phenotypes when present in biallelic, recessive states. This is very important for interpretation and filtering of variants from genomic data, as candidate variants cannot be dismissed based on perceived poor phenotypic fit.33

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for their consent and participation. I.J.C. is supported by NIH T32GM007454. We also thank M.M. Formosa (University of Malta) for her help with the alizarin red staining. C.D.K. is supported by the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowed Chair for Neuropathology as well as NIH AG005136. J.T.B. is supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists and the Arnold Lee Smith Endowed Professorship for Research Faculty Development. T.J.v.H. is supported by an Erasmus University Rotterdam fellowship.

Published: April 11, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Data can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.03.010.

Contributor Information

Tjakko J. van Ham, Email: t.vanham@erasmusmc.nl.

James T. Bennett, Email: jtbenn@uw.edu.

Web Resources

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

GeneMatcher, https://genematcher.org/

GME Variome, http://igm.ucsd.edu/gme

Iranome, http://iranome.ir/

Mutalyzer, https://mutalyzer.nl/index

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

UCSC Genome Browser, https://genome.ucsc.edu

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Cunningham C.L., Martínez-Cerdeño V., Noctor S.C. Microglia regulate the number of neural precursor cells in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:4216–4233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3441-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erblich B., Zhu L., Etgen A.M., Dobrenis K., Pollard J.W. Absence of colony stimulation factor-1 receptor results in loss of microglia, disrupted brain development and olfactory deficits. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagemeyer N., Hanft K.M., Akriditou M.A., Unger N., Park E.S., Stanley E.R., Staszewski O., Dimou L., Prinz M. Microglia contribute to normal myelinogenesis and to oligodendrocyte progenitor maintenance during adulthood. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:441–458. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1747-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paolicelli R.C., Bolasco G., Pagani F., Maggi L., Scianni M., Panzanelli P., Giustetto M., Ferreira T.A., Guiducci E., Dumas L. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science. 2011;333:1456–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squarzoni P., Oller G., Hoeffel G., Pont-Lezica L., Rostaing P., Low D., Bessis A., Ginhoux F., Garel S. Microglia modulate wiring of the embryonic forebrain. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wlodarczyk A., Holtman I.R., Krueger M., Yogev N., Bruttger J., Khorooshi R., Benmamar-Badel A., de Boer-Bergsma J.J., Martin N.A., Karram K. A novel microglial subset plays a key role in myelinogenesis in developing brain. EMBO J. 2017;36:3292–3308. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chitu V., Stanley E.R. Colony-stimulating factor-1 in immunity and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006;18:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginhoux F., Greter M., Leboeuf M., Nandi S., See P., Gokhan S., Mehler M.F., Conway S.J., Ng L.G., Stanley E.R. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbomel P., Thisse B., Thisse C. Zebrafish early macrophages colonize cephalic mesenchyme and developing brain, retina, and epidermis through a M-CSF receptor-dependent invasive process. Dev. Biol. 2001;238:274–288. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanley E.R., Berg K.L., Einstein D.B., Lee P.S., Pixley F.J., Wang Y., Yeung Y.G. Biology and action of colony--stimulating factor-1. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1997;46:4–10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199701)46:1<4::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baba Y., Ghetti B., Baker M.C., Uitti R.J., Hutton M.L., Yamaguchi K., Bird T., Lin W., DeLucia M.W., Dickson D.W., Wszolek Z.K. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids: clinical, pathologic and genetic studies of a new kindred. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;111:300–311. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konno T., Tada M., Tada M., Nishizawa M., Ikeuchi T. [Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS): a review of the literature on its clinical characteristics and mutations in the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor gene] Brain Nerve. 2014;66:581–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholson A.M., Baker M.C., Finch N.A., Rutherford N.J., Wider C., Graff-Radford N.R., Nelson P.T., Clark H.B., Wszolek Z.K., Dickson D.W. CSF1R mutations link POLD and HDLS as a single disease entity. Neurology. 2013;80:1033–1040. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rademakers R., Baker M., Nicholson A.M., Rutherford N.J., Finch N., Soto-Ortolaza A., Lash J., Wider C., Wojtas A., DeJesus-Hernandez M. Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nat. Genet. 2011;44:200–205. doi: 10.1038/ng.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundal C., Baker M., Karrenbauer V., Gustavsen M., Bedri S., Glaser A., Myhr K.-M., Haugarvoll K., Zetterberg H., Harbo H. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids with phenotype of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015;22:328–333. doi: 10.1111/ene.12572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wider C., Wszolek Z.K. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids: more than just a rare disease. Neurology. 2014;82:102–103. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Knaap M.S., Bugiani M. Leukodystrophies: a proposed classification system based on pathological changes and pathogenetic mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:351–382. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bianchin M.M., Martin K.C., de Souza A.C., de Oliveira M.A., Rieder C.R. Nasu-Hakola disease and primary microglial dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010;6 doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.17-c1. 2, 523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prinz M., Priller J. Microglia and brain macrophages in the molecular age: from origin to neuropsychiatric disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;15:300–312. doi: 10.1038/nrn3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oosterhof N., Kuil L.E., van der Linde H.C., Burm S.M., Berdowski W., van Ijcken W.F.J., van Swieten J.C., Hol E.M., Verheijen M.H.G., van Ham T.J. Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R) regulates microglia density and distribution, but not microglia differentiation in vivo. Cell Rep. 2018;24:1203–1217.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez-Tornos F.M., Briz C.G., Weiss L.A., Sebastián-Serrano A., Ares S., Navarrete M., Frangeul L., Galazo M., Jabaudon D., Esteban J.A., Nieto M. Cux1 enables interhemispheric connections of layer II/III neurons by regulating Kv1-dependent firing. Neuron. 2016;89:494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makrythanasis P., Maroofian R., Stray-Pedersen A., Musaev D., Zaki M.S., Mahmoud I.G., Selim L., Elbadawy A., Jhangiani S.N., Coban Akdemir Z.H. Biallelic variants in KIF14 cause intellectual disability with microcephaly. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;26:330–339. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0088-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Retterer K., Juusola J., Cho M.T., Vitazka P., Millan F., Gibellini F., Vertino-Bell A., Smaoui N., Neidich J., Monaghan K.G. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet. Med. 2016;18:696–704. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parichy D.M., Ransom D.G., Paw B., Zon L.I., Johnson S.L. An orthologue of the kit-related gene fms is required for development of neural crest-derived xanthophores and a subpopulation of adult melanocytes in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 2000;127:3031–3044. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y., Luo D., Lei Y., Hu W., Zhao H., Cheng C.H. A highly effective TALEN-mediated approach for targeted gene disruption in Xenopus tropicalis and zebrafish. Methods. 2014;69:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbomel P., Thisse B., Thisse C. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1999;126:3735–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oosterhof N., Kuil L.E., van Ham T.J. Microglial activation by genetically targeted conditional neuronal ablation in the zebrafish. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1559:377–390. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6786-5_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Ham T.J., Brady C.A., Kalicharan R.D., Oosterhof N., Kuipers J., Veenstra-Algra A., Sjollema K.A., Peterson R.T., Kampinga H.H., Giepmans B.N. Intravital correlated microscopy reveals differential macrophage and microglial dynamics during resolution of neuroinflammation. Dis. Model. Mech. 2014;7:857–869. doi: 10.1242/dmm.014886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cipriani S., Nardelli J., Verney C., Delezoide A.L., Guimiot F., Gressens P., Adle-Biassette H. Dynamic expression patterns of progenitor and pyramidal neuron layer markers in the developing human hippocampus. Cereb. Cortex. 2016;26:1255–1271. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hevner R.F., Daza R.A., Englund C., Kohtz J., Fink A. Postnatal shifts of interneuron position in the neocortex of normal and reeler mice: evidence for inward radial migration. Neuroscience. 2004;124:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber W., von Heydebreck A., Sültmann H., Poustka A., Vingron M. Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(Suppl 1):S96–S104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., Smyth G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monies D., Maddirevula S., Kurdi W., Alanazy M.H., Alkhalidi H., Al-Owain M., Sulaiman R.A., Faqeih E., Goljan E., Ibrahim N. Autozygosity reveals recessive mutations and novel mechanisms in dominant genes: implications in variant interpretation. Genet. Med. 2017;19:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rees J.H., Vaughan R.W., Kondeatis E., Hughes R.A. HLA-class II alleles in Guillain-Barré syndrome and Miller Fisher syndrome and their association with preceding Campylobacter jejuni infection. J. Neuroimmunol. 1995;62:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meireles A.M., Shiau C.E., Guenther C.A., Sidik H., Kingsley D.M., Talbot W.S. The phosphate exporter xpr1b is required for differentiation of tissue-resident macrophages. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1659–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nandi S., Gokhan S., Dai X.M., Wei S., Enikolopov G., Lin H., Mehler M.F., Stanley E.R. The CSF-1 receptor ligands IL-34 and CSF-1 exhibit distinct developmental brain expression patterns and regulate neural progenitor cell maintenance and maturation. Dev. Biol. 2012;367:100–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo J., Elwood F., Britschgi M., Villeda S., Zhang H., Ding Z., Zhu L., Alabsi H., Getachew R., Narasimhan R. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling in injured neurons facilitates protection and survival. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:157–172. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chitu V., Stanley E.R. Regulation of embryonic and postnatal development by the CSF-1 receptor. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2017;123:229–275. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett F.C., Bennett M.L., Yaqoob F., Mulinyawe S.B., Grant G.A., Hayden Gephart M., Plowey E.D., Barres B.A. A combination of ontogeny and CNS environment establishes microglial identity. Neuron. 2018;98:1170–1183.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pridans C., Sauter K.A., Baer K., Kissel H., Hume D.A. CSF1R mutations in hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids are loss of function. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3013. doi: 10.1038/srep03013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams S.J., Kirk A., Auer R.N. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP): Integrating the literature on hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) and pigmentary orthochromatic leukodystrophy (POLD) J. Clin. Neurosci. 2018;48:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffmann S., Murrell J., Harms L., Miller K., Meisel A., Brosch T., Scheel M., Ghetti B., Goebel H.H., Stenzel W. Enlarging the nosological spectrum of hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS) Brain Pathol. 2014;24:452–458. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bianchin M.M., Lima J.E., Natel J., Sakamoto A.C. The genetic causes of basal ganglia calcification, dementia, and bone cysts: DAP12 and TREM2. Neurology. 2006;66:615–616. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216105.11788.0f. author reply 615–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chouery E., Delague V., Bergougnoux A., Koussa S., Serre J.L., Mégarbané A. Mutations in TREM2 lead to pure early-onset dementia without bone cysts. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:E194–E204. doi: 10.1002/humu.20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paloneva J., Kestilä M., Wu J., Salminen A., Böhling T., Ruotsalainen V., Hakola P., Bakker A.B., Phillips J.H., Pekkarinen P. Loss-of-function mutations in TYROBP (DAP12) result in a presenile dementia with bone cysts. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:357–361. doi: 10.1038/77153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiialainen A., Hovanes K., Paloneva J., Kopra O., Peltonen L. Dap12 and Trem2, molecules involved in innate immunity and neurodegeneration, are co-expressed in the CNS. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005;18:314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otero K., Turnbull I.R., Poliani P.L., Vermi W., Cerutti E., Aoshi T., Tassi I., Takai T., Stanley S.L., Miller M. Macrophage colony stimulating factor induces the proliferation and survival of macrophages via a pathway involving DAP12 and β-catenin. Nat. Immunol. 2009;999:734–743. doi: 10.1038/ni.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paloneva J., Mandelin J., Kiialainen A., Bohling T., Prudlo J., Hakola P., Haltia M., Konttinen Y.T., Peltonen L. DAP12/TREM2 deficiency results in impaired osteoclast differentiation and osteoporotic features. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:669–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Codjia P., Ayrignac X., Mochel F., Mouzat K., Carra-Dalliere C., Castelnovo G., Ellie E., Etcharry-Bouyx F., Verny C., Belliard S. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia: An MRI study of 16 French cases. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018;39:1657–1661. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cuadrado E., Jansen M.H., Anink J., De Filippis L., Vescovi A.L., Watts C., Aronica E., Hol E.M., Kuijpers T.W. Chronic exposure of astrocytes to interferon-α reveals molecular changes related to Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. Brain. 2013;136:245–258. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wimmer K., Kratz C.P., Vasen H.F., Caron O., Colas C., Entz-Werle N., Gerdes A.M., Goldberg Y., Ilencikova D., Muleris M., EU-Consortium Care for CMMRD (C4CMMRD) Diagnostic criteria for constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome: suggestions of the European consortium ‘care for CMMRD’ (C4CMMRD) J. Med. Genet. 2014;51:355–365. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.