Abstract

Introduction:

Since October 2012, the combined tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) has been recommended in the United States during every pregnancy.

Methods:

In this observational study from the Vaccine Safety Datalink, we describe receipt of Tdap during pregnancy among insured women with live births across seven health systems. Using a retrospective matched cohort, we evaluated risks for selected medically attended adverse events in pregnant women, occurring within 42 days of vaccination. Using a generalized estimating equation, we calculated adjusted incident rate ratios (AIRR).

Results:

Our vaccine coverage cohort included 438,487 live births between January 1, 2007 and November 15, 2013. Across the coverage cohort, 14% received Tdap during pregnancy. By 2013, Tdap was administered during pregnancy in 41.7% of live births, primarily in the 3rd trimester. Our vaccine safety cohort included 53,885 vaccinated and 109,253 matched unvaccinated pregnant women. There was no increased risk for a composite outcome of medically attended acute adverse events within 3 days of vaccination. Similarly, across the safety cohort, over a 42 day window, incident neurologic events, thrombotic events, and new onset proteinuria did not differ by maternal receipt of Tdap. Among women receiving Tdap at 20 weeks gestation or later, as compared to their matched controls, there was no increased risk for gestational diabetes or cardiac events while venous thromboembolic events and thrombocytopenia were diagnosed within 42 days of vaccination at slightly decreased rates.

Conclusion:

Tdap coverage during pregnancy increased from 2007 through 2013, but was still below 50%. No acute maternal safety signals were detected in this large cohort.

Keywords: Tdap, Vaccine coverage, Vaccine safety, Maternal vaccination

1. Introduction

Outbreaks of pertussis remain a persistent public health challenge across the United States and abroad [1–5]. Although pertussis maybemildinolderchildrenandadolescents,infantswho contract pertussis are at risk for severe morbidity and mortality. These infants may be too young for vaccination and must rely on vaccination of close contacts (cocooning) and passive transfer of maternal antibodies for protection [6]. Third trimester maternal vaccination is likely to be the most effective strategy available for preventing pertussis in newborns [7–9].

The combined tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) was first recommended for routine administration during pregnancy by the California Department of Health in 2010 [10]. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) followed in 2011 with national recommendations to administer Tdap at 20 weeks gestation or later to all pregnant women not previously vaccinated [11]. In fall of 2012 the ACIP recommendations were revised, recommending Tdap administration in every pregnancy, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks gestation [12].

To date there are limited published data on receipt of Tdap among pregnant women, especially following the 2012 ACIP guidelines to administer Tdap to women in every pregnancy. In prior work by our group, among live births in 2012 across seven large health systems, less than 20% of women received Tdap during pregnancy [13]. Similarly, in the fall of 2011, data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System demonstrated that, among women with live births in 16 states and New York City, 9.8% received pertussis vaccine during pregnancy [14]. More recent data from Texas and Wisconsin have demonstrated higher Tdap uptake for pregnant women in 2013 and 2014 [15,16].

Despite these observed increases, many women remain hesitant to receive Tdap during pregnancy due to concerns regarding safety for themselves or their babies [17,18]. Although published data to date on the safety of maternal Tdap, including from one small clinical trial [19] and several observational studies [20–25] have been generally reassuring, continued postmarketing surveillance of maternal Tdap vaccination is needed [26]. Goals of the current study were two-fold: (1) to provide updated estimates of Tdap coverage during pregnancy among insured women within the Vaccine Safety Datalink and (2) to evaluate risks for selected acute adverse events occurring 0–42 days following maternal Tdap vaccination.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

In this observational cohort study of pregnancies at seven Vaccine Safety Datalink sites, we described Tdap coverage during pregnancy and, using a matched cohort design, we evaluated risks for acute maternal adverse events following maternal Tdap vaccination.

2.2. Study population: Vaccine coverage and vaccine safety cohorts

The Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Safety Office and nine large integrated health care systems in the United States [27]. For the current study, among seven participating VSD sites, with members in six states (California, Colorado, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington and Wisconsin), pregnancies were identified from claims, administrative and electronic health data, using a validated algorithm [28]. This algorithm, used in several prior studies of vaccine coverage [13,29] and vaccine safety during pregnancy [20,30,31], identifies pregnancies, pregnancy outcomes, pregnancy end dates and gestational age at end of pregnancy. The algorithm uses gestational age at end of pregnancy and pregnancy end date to estimate the pregnancy start date, equivalent to the last menstrual period (LMP). Cases of gestational trophoblastic disease, ectopic pregnancy, and pregnancies ending in spontaneous abortion, therapeutic abortion, stillbirth, or with an unknown pregnancy outcome were excluded.

For our vaccine coverage cohort, we first identified pregnancies with live births between January 1, 2007 and November 15, 2013. Each pregnancy was recorded as a unique event. Women with 2 or more pregnancies during the observation period could be included more than once. To ensure capture of data on vaccine exposures, women were required to have continuous insurance enrollment for the period 6 months prior to pregnancy start, through pregnancy and 6 weeks following the end of pregnancy or postpartum. For the remaining eligible pregnancies, with a live birth outcome and continuous insurance enrollment, we then obtained all vaccine records from the standardized VSD vaccine files. These files capture vaccines primarily through EHR-linked registries as well as from medicalorpharmacyclaimsandstate-basedvaccineregistries. Similar to prior studies, Tdap vaccines were classified as occurring during pregnancy if administered starting 8 days after LMP through 7 days before delivery [13]. These cut-offs were assigned to account for uncertainty regarding the LMP and specifically to avoid misclassification of postpartum vaccinations as occurring during pregnancy. For Tdap vaccines administered during pregnancy, gestational week of vaccination was defined by subtracting the vaccination date from the estimated pregnancy start date. First trimester was defined as <14 weeks gestation, second trimester as 14 weeks to <28 weeks and third trimester as ≥28 weeks gestation.

For the vaccine safety cohort, we started with the vaccine coverage cohort, including both vaccinated and unvaccinated women, and applied the following additional exclusions: multiple gestation pregnancies, women with no medical care during pregnancy and women who received a live virus vaccine. Women receiving Tdap during pregnancy were matched with up to 3 unexposed women using an optimal matching algorithm. Match variables were maternal age (within 1 year), site, and estimated pregnancy start date (within 7 days). Unvaccinated women were assigned an index date equivalent to the gestational age at vaccination for their match.

Covariates of interest included: the Kotelchuck Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index (APNCU) [32,33] derived from administrative and electronic health record data within the VSD, the number of hospitalizations from LMP to vaccine/index date, and maternal age at delivery. In addition, we evaluated census tract poverty level, defined for each subject as the percent of families in their census tract with income below 150% of the federal poverty level.

2.3. Safety outcomes, exposure periods and risk windows

Outcomes, exposure periods and risk windows were chosen a priori based on prior work by our group on vaccine safety during pregnancy [25,30,31], biologic plausibility [34], and the expected timing of both Tdap vaccination [12] and specific outcomes during pregnancy. All outcomes were identified using diagnostic codes (ICD-9 codes) assigned at inpatient, emergency department or outpatient visits. Washout periods or specific exclusions were applied to ensure that outcomes were incident or new events and not conditions present prior to vaccination/index date in unvaccinated. These outcome specific exclusions are defined in Appendix Table 1. For all pregnancies, we evaluated risks for medically attended allergic reactions, fever, malaise, seizures, altered mental status and local and other reactions for 0–3 days following vaccination/index date. We also evaluated risks for medically attended neurologic events (autonomic disorders, cranial nerve disorders, CNS degeneration/demyelinating conditions, peripheral neuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, meningoencephalitides, movement disorders, paralytic syndromes, and spinocerebellar disease), proteinuria, and venous thromboembolism for 0–42 days following vaccination. Events occurring on the day of vaccination were limited to emergency department or inpatient visits.

For the subset ofwomenvaccinatedat20weeksgestation or later, (consistent with the 2011 ACIP recommendations) we evaluated risks for incident gestational diabetes, thrombocytopenia, cardiac events (cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, pericarditis, and heart failure), and venous thromboembolism within 42 days of vaccination. Risk windows were truncated at delivery, except for venous thromboembolism and cardiac events, which included the postpartum period. A full list of outcomes, exposure periods, risk windows, and additional outcome specific exclusions, is included as an online Table.

2.4. Analyses

For the vaccine coverage cohort, we described receipt of Tdap during pregnancy by year and by trimester of pregnancy. To evaluate safety outcomes, we first compared baseline characteristics for women who did and did not receive Tdap during pregnancy. For each outcome we evaluated incident rates per 10,000 in vaccinated and unvaccinated. Using generalized estimating equation method, with a Poisson distribution and log link, we calculated adjusted incident rate ratios (AIRR). Adjustments were made for patterns of care prior to vaccination date/index date, APNCU index and having an inpatient encounter before vaccination date/index date.

This study was approved by the IRBs of all participating sites and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with a waiver of informed consent.

3. Results

3.1. Tdap coverage during pregnancy

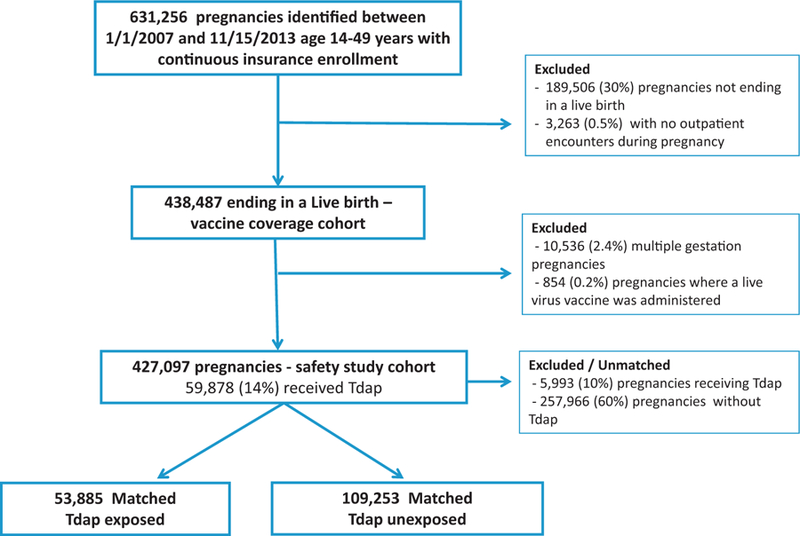

Across the 7 VSD sites we identified 631,256 pregnancies in women 14–49 years of age with continuous insurance enrollment and pregnancy end dates between January 1, 2007 and November 15, 2013. Of these, 441,750 ended in a live birth (Fig. 1). In addition, we excluded 3263 (0.5%) women with no outpatient encounters during pregnancy. Thus, our vaccine coverage cohort was comprised of 438,487 pregnancies. From 2007 to 2013, receipt of Tdap during pregnancy was 14%. The first increases in Tdap coverage occurred in 2010. By 2013 in 41.7% of live births, women received Tdap during pregnancy and most vaccination (75%) occurred in the third trimester. (Fig. 2) Receipt of Tdap did not vary substantially based on the presence of most maternal comorbidities.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart.

Fig. 2.

Receipt of Tdap during pregnancy by trimester, live births between 2007 and 2013.

3.2. Acute safety

For our evaluation of the acute safety of maternal Tdap, from the 438,487 live births in the coverage cohort, described above, we excluded 10,536 (2.4%) with multiple births and 854 (0.2%) who received a live virus vaccine. Thus, our safety study cohort was comprised of 427,097 singleton pregnancies, of whom 59,878 (14%) received Tdap during pregnancy. Of these, 5993 (10%) of Tdap exposed were unmatched. Our final matched safety cohort was comprised of 53,885 Tdap exposed pregnancies and 109,253 pregnancies unexposed to Tdap during the same period (Fig. 1).

Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of our matched safety cohort. Most women were between 20 and 34 years of age (73%) and a vast majority (>95%) received medical care in their first trimester. As compared to the unvaccinated, women receiving Tdap during pregnancy were slightly less likely to be hospitalized before the vaccine/index date (8.3% versus 9.1%) and they were more likely to have adequate/plus prenatal care (78.8% versus 74.6%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of matched cohort, including women receiving Tdap during pregnancy and those who did not.

| Tdap during pregnancy N = 53,885 | Unvaccinated N = 109,253 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine/index date trimester | ** | ||

| First | 7.6% | 9.5% | |

| Second | 34.2% | 35.8% | |

| Third | 58.2% | 54.7% | |

| Vaccine/index date ≥20 weeks | 81.8% | 78.8% | ** |

| Maternal age | <.0001 | ||

| <20 years | 3.4% | 4.1% | |

| 20–34 | 73.7% | 73.2% | |

| ≥35 years | 22.9% | 22.7% | |

| Any high risk conditiona | 23.0% | 22.8% | .33 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.9% | 1.9% | .77 |

| Heart disease (not hypertension) | 2.0% | 2.1% | .44 |

| Hypertension | 2.7% | 3.0% | .0009 |

| Pulmonary disease | 10.7% | 11.2% | <.0001 |

| Neurologic condition | 0.9% | 0.9% | .70 |

| Hospitalization prior to vaccine/index date | 8.3% | 9.1% | <.0001 |

| Prenatal care in 1st trimester | 95.9% | 95.0% | <.0001 |

| APNCU index | <.0001 | ||

| Adequate/plus | 78.8% | 74.6% | |

| Intermediate | 17.4% | 19.8% | |

| Inadequate | 3.8% | 5.7% | |

| Mean percent of families in census tract with income below 150% of federal poverty level | 17.0% | 17.2% | .0039 |

| Gestational age at delivery in weeks | 39.0 | 38.8 | <.0001 |

Rates and AIRRs for the acute safety outcomes are in Table 2. Among 53,885 women receiving Tdap at any time during pregnancy, 43 had a medically attended event (allergic reaction, fever and malaise, seizure, altered mental status, or local or other reaction) 0–3 days following vaccination, for a rate of 8.1 per 10,000. For the 109,253 controls, who did not receive Tdap during pregnancy, there were 74 events within 3 days of their matched index date, for a rate of 6.8 per 10,000. The AIRR was 1.19 (95% CI: 0.81–1.73). Of the 0–3 day outcomes, there was an increased rate of medical visits for fever following Tdap (2.8 per 10,000) as compared to the matched 3-day window in the unvaccinated cohort (<1 per 10,000). The AIRR for medically attended fever within 3 days following vaccination was 5.4 (95% CI: 2.1–13.9).

Table 2.

Risks for acute adverse events, 0–3 and 0–42 days following maternal Tdap, for the full matched cohort and those vaccinated at 20 weeks gestation or later.

| Tdap during pregnancy N = 53,885 Rate per 10,000 (N) | Unvaccinated N = 109,253 Rate per 10,000 (N) | Adjustedrate ratioa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any 0–3 day eventb | 8.1 (43) | 6.8 (74) | 1.19 (0.81–1.73) |

| Allergic reaction | 1.3 (7) | 1.3 (14) | |

| Malaise | <1 (3) | 1.2 (13) | |

| Fever | 2.8 (15) | <1(6) | |

| Seizures | <1 (1) | <1(1) | |

| Altered mental status | − (0) | <1(3) | |

| Local and other reactions | 3.4 (18) | 3.9 (42) | |

| Any 0–42 day neurologic eventb | 9.6 (51) | 9.6 (104) | 0.98 (0.70–1.37) |

| Autonomic disorders | <1 (2) | <1 (7) | |

| Cranial nerve disorders | 3.5 (19) | 3.5 (38) | |

| CNS degeneration/demyelinating | 0 (0) | <1 (3) | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 3.4 (18) | 2.5 (27) | |

| Guillain-Barrésyndrome | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Meningoencephalitides | <1 (3) | <1 (9) | |

| Movement disorders | 2.4 (13) | 2.9 (32) | |

| Paralytic syndromes | <1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Spinocerebellar disease | 0 (0) | <1 (6) | |

| Proteinuria | 17.9 (84) | 21.9 (207) | 0.81 (0.6–1.05) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 4.1 (22) | 6.3 (69) | 0.65 (0.40–1.05) |

| Tdap ≥20 weeks gestation N = 44,063 | Unvaccinated N = 86,057 | Adjustedrate ratioa (95% CI) | |

| Gestational diabetes | 275 (1101) | 287 (2263) | 0.96 (0.89–1.03) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 57 (249) | 68 (579) | 0.85 (0.73–0.98) |

| VenousThromboembolism | 4.3 (19) | 7.6 (65) | 0.58 (0.35–0.97) |

| Cardiac events | 20.4 (90) | 23.0 (198) | 0.90 (0.70–1.15) |

| Pericarditis | <1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Myocarditis | <1 (1) | 1 (9) | |

| Cardiomyopathy | 17.5 (77) | 21.5 (185) | |

| Heart failure | 7.7 (34) | 6.4 (55) | |

Adjusted for Kotelchuck Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index (APNCU), hospitalization prior to vaccination/index date, mean percent of families in census tract with income below 150% of the federal poverty level.

Events occurring on the day of vaccination (Day 0) were required to be emergency department or inpatient diagnoses.

Neurologic events within 42 days following maternal Tdap occurred at the same rate of 9.6 per 10,000 in vaccinated and unvaccinated. Similarly, rates for proteinuria and venous thromboembolism did not differ significantly between the Tdap exposed and unexposed groups, for the full safety cohort.

InthesubsetofwomenreceivingTdapat≥20weeksgestation, as compared to theirunvaccinatedmatches,therewas no increased risk for incident gestational diabetes, thrombocytopenia, venous thromboembolism or cardiac events (myocarditis, pericarditis, cardiomyopathy, or heart failure) within 42 days of vaccination. (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Maternal Tdap vaccination remains an important strategy for preventing pertussis in newborns. Current recommendations from ACIP are to administer Tdap in the third trimester during every pregnancy [12]. This study provides important and needed data on Tdap coverage or adherence with the current recommendations. Among insured women with live births from 6 states, in 201,341.7% were vaccinated during pregnancy, with most vaccinations occurring in the third trimester. Results from our analyses of acute events following maternal vaccination provides further evidence of the safety of maternal Tdap, for the outcomes studied.

Our data on Tdap coverage, with an increase in receipt of maternal Tdap occurring in 2013, is promising, especially as compared to reports from the VSD [13] and the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System [14] for prior years. Nevertheless, there is still much room for improvement. Educational efforts could be focused on practices, health systems and public health practitioners to facilitate vaccination by obstetricians as part of routine prenatal care. Education of expectant mothers regarding the importance, safety, and effectiveness of maternal Tdap is also needed. Reports from single centers have demonstrated high Tdap coverage in pregnancy [15,24,35]; however, the challenge remains to increase uptake in larger, more diverse populations.

In our evaluation of Tdap safety, we focused on potential adverse events occurring in mothers, within 42 days of vaccination. These outcomes have not been addressed in most prior observational studies of maternal Tdap safety [20–22,24] but many, including medically attended allergic and local reactions and acute neurologic events, havebeenusedinassessmentsofTdapsafety in non-pregnant populations [36,37]. In addition, these acute maternal safety outcomes have been evaluated by our group in prior studies of maternal influenza vaccination [30,31,38]. Similar to our studies of maternal influenza vaccination [30,38], we found no increased risks for acute neurologic events, proteinuria, thrombocytopenia or venous thromboembolism following maternal vaccination.

We found no increased risk for cardiac events within 42 days of maternal Tdap. There have been three case reports of adolescents or young adults developing acute myopericarditis following receipt of multiple vaccines including a tetanus or pertussis containing vaccine, with no alternative etiology for the myopericarditis identified [39–41]. In all three cases, symptoms developed suddenly, within 2–3 days of vaccination. Inaddition, from 2005 through 2007, three cases of myopericarditis in young adults following Tdap were reported to the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) [42]. In the current study we detected only one myocarditis and two pericarditis cases following maternal Tdap and 9 myocarditis cases among pregnant women who did not receive Tdap, with no consistent pattern of increased incidence following vaccination.

Consistent with our prior studies of maternal influenza vaccination and a recent study on risks of concomitant maternal Tdap and influenza vaccination, we did not observe an increased risk for a composite outcome of 0–3 day events that included fever, malaise, allergic, local and other reactions following maternal Tdap [25,30,38]. Medically attended fever within 3 days of vaccination/index date was more common in vaccinated than unvaccinated, with rates of 2.8 per 10,000 versus <1 per 10,000, respectively, with an AIRR of 5.4 (95% CI: 2.1–13.9). However, in both groups rates for medically attended fever were quite low. This rate of a medically attended safety outcome differs substantially from data collected during the course of a clinical trial, where outcomes are not dependent on seeking medical care. In 2014 Muñ oz and colleagues reported on a Phase 1–2 double blindrandomized, controlled trial of Tdap during pregnancy which included 33 women who received Tdap during pregnancy. In this study, 3% of women receiving Tdap during pregnancy experienced fever post-vaccination [19].

Strengths of the current study included our large sample size and use of validated methods to identify pregnancies and gestational age at vaccination [28]. In addition, in our assessment of maternal vaccine safety, our matched cohort approach reduced bias due to seasonal effects or secular trends by comparing vaccinated and unvaccinated women, with risk windows aligned by both calendar week and gestational age.

Several limitations to our findings should be noted. First, for our assessment of Tdap coverage, our cohort only includes women with live births and continuous health insurance and from specific geographical regions. Tdap coverage during pregnancy may be lower in women with interrupted insurance coverage and in women from other regions of the United States. In addition, our data is limited to pregnancies for the period 2007–2013. We may be missing more recent increases in Tdap coverage. Second, for our evaluation of Tdap safety, analyses were limited to specific prespecified maternal events. These outcomes do not represent all relevant outcomes for assessment of maternal vaccine safety and thus our findings should be considered in conjunction with other large post-marketing studies of maternal Tdap safety [20,21,25]. For example, risksfor stillbirthfollowing maternalTdap vaccination, an important outcome when evaluating maternal vaccine safety, would require chart confirmation to assess timing and possible etiology of fetal demise. Finally, as an observational study, unmeasured or residual confounding is possible.

5. Conclusions

In this large, multisite, observational study, we found that in the year following ACIP recommendations to administer Tdap in every pregnancy, 41.7% of women with live births across multiple health systems were vaccinated. We did not observe increased risks for any pre-specified maternal safety outcomes within 42 days of vaccination. Continued efforts to promote Tdap vaccination during pregnancy are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Contract 200-2012-53526. Findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Klein has received research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofl Pasteur, Merck & CO, Pflzer, Nuron Biotech, Medimmune, Novartis and Protein Science. Dr. Naleway has received research support from GlaxoSmithKlein and Pflzer. Dr. Cheetham receives research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.046.

References

- [1].Pertussis epidemic—Washington. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep July 20 2012. 2012;61(28):517–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cherry JD. Epidemic pertussis in 2012—the resurgence of a vaccine-preventable disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367(9):785–7. August 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Shechter R, Talarico J, Watt J, et al. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr 2012;161(December (6)):1091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Winter K, Glaser C, Watt J, Harriman K. Pertussis Epidemic – California, 2014. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63(48):1129–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].van Hoek AJ, Campbell H, Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Miller E. The number of deaths among infants under one year of age in England with pertussis: results of a capture/recapture analysis for the period 2001 to 2011. Euro surveill 2013;18(9). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vilajeliu A, Gonce A, Lopez M, Costa J, Rocamora L, Rios J, et al. Combined tetanus-diphtheria and pertussis vaccine during pregnancy: transfer of maternal pertussis antibodies to the newborn. Vaccine 2015;33(February (8)):1056–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Terranella A, Asay GR, Messonnier ML, Clark TA, Liang JL. Pregnancy dose Tdap and postpartum cocooning to prevent infant pertussis: a decision analysis. Pediatrics 2013;131(June (6)):e1748–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, Kara E, Donegan K, et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet 2014, July. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [9].Healy CM, Rench MA, Baker CJ. Importance of timing of maternal combined tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization and protection of young infants. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56(February (4)):539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].CDPH Broadens recommendations for vaccinating against pertussis: immunization key to controlling whooping cough http://www.cdph.ca.gov/Pages/PH10-048.aspx [accessed on 02.12.13].

- [11].Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged <12 months – Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60(October (41)):1424–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria tox-oid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62(February (7)):131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, Naleway AL, Klein NP, Cheetham TC. Receipt of pertussis vaccine during pregnancy across 7 Vaccine Safety Datalink Sites. Prev Med 2014, June. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [14].Ahluwalia IB, Ding H, D’Angelo D, Shealy KH, Singleton JA, Liang J, et al. Tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis vaccination coverage before, during, and after pregnancy – 16 States and new york city, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(May (19)):522–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Healy CM, Ng N, Taylor RS, Rench MA, Swaim LS. Tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine uptake during pregnancy in a metropolitan tertiary care center. Vaccine 2015, July. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [16].Koepke R,Kahn D,Petit AB, Schauer SL,Hopfensperger DJ,Conway JH, et al. Pertussis and InfluenzaVaccination Among Insured Pregnant Women – Wisconsin, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(July (27)): 746–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chamberlain AT, Seib K, Ault KA, Orenstein WA, Frew PM, Malik F, et al. Factors associated with intention to receive influenza and tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines during pregnancy: a focus on vaccine hesitancy and perceptions of disease severity and vaccine safety. PLoS Curr 2015:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Payakachat N, Hadden KB, Ragland D. Promoting Tdap immunization in pregnancy: associations between maternal perceptions and vaccination rates. Vaccine 2015, September. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [19].Munoz FM, Bond NH, Maccato M, Pinell P, Hammill HA, Swamy GK, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of tetanus diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy in mothers and infants: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc 2014;311(May (17)):1760–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind HS, Klein NP, Cheetham TC, Nale-way A, et al. Evaluation of the association of maternal pertussis vaccination with obstetric events and birth outcomes. J Am Med Assoc 2014;312(November (18)):1897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Donegan K, King B, Bryan P. Safety of pertussis vaccination in pregnant women in UK: observational study. Br Med J 2014;349:g4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shakib JH, Korgenski K, Sheng X, Varner MW, Pavia AT, Byington CL. Tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis vaccine during pregnancy: pregnancy and infant health outcomes. J Pediatr 2013;163(November (5)), 1422–1426; e1421–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zheteyeva YA, Moro PL, Tepper NK, Rasmussen SA, Barash FE, Revzina NV, et al. Adverse event reports after tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccines in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207(July (1)), 59; e51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Morgan JL, Baggari SR, McIntire DD, Sheffleld JS. Pregnancy outcomes after antepartum tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(June (6)):1433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, Weintraub ES, Vazquez-Benitez G, McNeil MM, et al. Safety of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis and influenza vaccinations in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015, October. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [26].The National Vaccine Advisory Committee: reducing patient and provider barriers to maternal immunizations: approved by the National Vaccine Advisory Committee on June 11, 2014. Public Health Rep 2015;130(January–February (1)):10–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Baggs J, Gee J, Lewis E, Fowler G, Benson P, Lieu T,et al. TheVaccine Safety Datalink: a model for monitoring immunization safety. Pediatrics 2011;127(May (Suppl 1)):S45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Naleway AL, Gold R, Kurosky S, Riedlinger K, Henninger ML, Nordin JD, et al. Identifying pregnancy episodes, outcomes, and mother-infant pairs in the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Vaccine 2013;31(June (27)):2898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Naleway AL, Kurosky S, Henninger ML, Gold R, Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, et al. Vaccinations givenduringpregnancy, 2002–2009:adescriptivestudy. AmJ Prev Med 2014;46(February (2)):150–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, Lee GM, Naleway AL. Monovalent H1N1 influenza vaccine safety in pregnant women, risks for acute adverse events. Vaccine 2014;32(September (39)):4985–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, Naleway A, Lee G, Nordin JD. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122(September (3)):659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kotelchuck M The Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index: its US distribution and association with low birthweight. Am J Public Health 1994;84(September (9)):1486–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kotelchuck M An evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a proposed Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index. Am J Public Health 1994;84(September (9)):1414–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Christian LM, Porter K, Karlsson E, Schultz-Cherry S, Iams JD. Serum proinflammatory cytokine responses to influenza virus vaccine among women during pregnancy versus non-pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 2013;70(July (1)):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Goldfarb IT,Little S,Brown J,Riley LE.Use ofthe combinedtetanus-diphtheria and pertussis vaccine during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211(September (3)), 299; e291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tseng HF, Sy LS, Qian L, Marcy SM, Jackson LA, Glanz J, et al. Safety of a tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine when used off-label in an elderly population. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56(February (3)):315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yih WK, Nordin JD, Kulldorff M, Lewis E, Lieu TA, Shi P, et al. An assessment of the safety of adolescent and adult tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine, using active surveillance for adverse events in the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Vaccine 2009;27(July (32)):4257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Nichol K, Lipkind H, Naleway A, et al. Maternal safety of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121(March (3)):519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Thanjan MT, Ramaswamy P, Lai WW, Lytrivi ID. Acute myopericarditis after multiple vaccinations in an adolescent: case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics 2007;119(June (6)):e1400–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Boccara F, Benhaiem-Sigaux N, Cohen A. Acute myopericarditis after diphtheria, tetanus, and polio vaccination. Chest 2001;120(August (2)):671–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dilber E, Karagoz T, Aytemir K, Ozer S, Alehan D, Oto A, et al. Acute myocarditis associated with tetanus vaccination. Mayo Clin Proc, Mayo Clin 2003;78(November (11)):1431–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chang S, O’Connor PM, Slade BA, Woo EJ. U.S. Postlicensure safety surveillance for adolescent and adult tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis vaccines: 2005–2007. Vaccine 2013;31(February (10)):1447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.