Abstract

We report a recurrent CNOT1 de novo missense mutation, GenBank: NM_016284.4; c.1603C>T (p.Arg535Cys), resulting in a syndrome of pancreatic agenesis and abnormal forebrain development in three individuals and a similar phenotype in mice. CNOT1 is a transcriptional repressor that has been suggested as being critical for maintaining embryonic stem cells in a pluripotent state. These findings suggest that CNOT1 plays a critical role in pancreatic and neurological development and describe a novel genetic syndrome of pancreatic agenesis and holoprosencephaly.

Keywords: neonatal, diabetes, pancreas, agenesis, genetics, mutation, development, neurological

Main Text

Discovering genes with mutations causal of pancreatic agenesis is crucial to identifying factors needed for pancreatic development. To date, pathogenic variants in six genes (PTF1A [MIM: 615935], PDX1 [MIM: 260370], GATA6 [MIM: 600001], GATA4 [MIM: 600576], HNF1B [MIM: 137920], and RFX6 [MIM: 615710]) have been reported to severely affect pancreatic development and result in pancreatic agenesis.1 Gene discovery in pancreatic agenesis has shown both similarities and marked differences between pancreatic development in human and mouse. In both species, complete loss of function of PTF1A, PDX1, or RFX6 results in pancreatic agenesis. In contrast, while haploinsufficiency of GATA6 is a common cause of pancreatic agenesis in humans,2 in mice Gata6 knockout does not result in abnormal pancreatic development.3 Knowledge of human pancreatic development is essential to guide progress of beta-cell replacement therapy for people with type 1 diabetes.

We investigated an international cohort of 107 individuals diagnosed with pancreatic agenesis—defined by requiring both endocrine (insulin) and exocrine (pancreatic enzymes) replacement therapy within the first 6 months of life—and identified a mutation in a known gene in 98 of them (Table S1). To identify de novo mutations in the remaining nine subjects, exome sequencing was performed for the probands and both their unaffected parents when available (n = 7) (Supplemental Subjects and Methods).

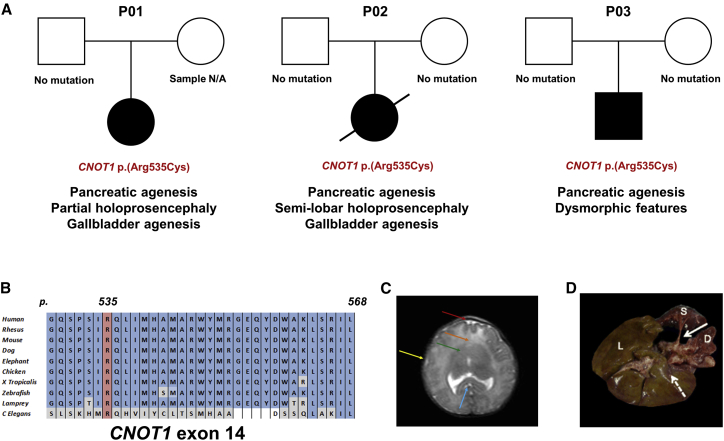

We identified a heterozygous missense mutation in CNOT1 (MIM: 604917; GenBank: NM_016284.4; c.1603C>T [p.Arg535Cys]) in three individuals with pancreatic agenesis. The variant had arisen de novo in two of them and was not present in the DNA sample from the 3rd individual’s father (maternal sample was not available for testing) (Figure 1A, Tables S2 and S3). We confirmed these results by Sanger sequencing (Supplemental Subjects and Methods, Figure S1). The p.Arg535Cys variant is absent from dbSNP138, DECIPHER, and GnomAD and affects a residue which is highly conserved across species (up to C. elegans) (Figure 1B). All three in silico prediction tools used (AlignGVGD, PolyPhen2, and SIFT accessed through AlamutVisual) predicted the variant to have a deleterious effect on protein function (Supplemental Subjects and Methods).

Figure 1.

Genetic and Clinical Findings in Individuals with Pancreatic Agenesis

(A) Partial pedigrees and clinical features of the three individuals with the heterozygous CNOT1 p.Arg535Cys mutation.

(B) Conservation of CNOT1 residues 529 to 568 across 10 representative species. Residue p.Arg535 is highlighted in red. Residues identical to the human CNOT1 protein are highlighted in blue, differences are highlighted in gray.

(C) Coronal brain MRI of P02 showing absence of the anterior interhemispheric fissure (red arrow), fusion of the frontal lobes (orange arrow), absence of frontal horns (green arrow), absence of the sylvian fissures (yellow arrow). Splenium of the corpus callosum is visible (blue arrow).

(D) Post mortem image of P02’s liver (L), spleen (S), and duodenum (D). White arrow shows the orthotopic location of the pancreas, which is absent. Dashed arrow indicated site in which the absent gallbladder would be expected to be.

The three individuals who were heterozygous for the CNOT1 p.Arg535Cys variant had strikingly similar clinical features (see Supplemental Note). In addition to pancreatic agenesis, all three had definite (n = 2) or possible holoprosencephaly (Figure 1A, Table S4), a disorder in which the prosencephalon (forebrain of the embryo) fails to develop into two hemispheres. P01 and P02 (who was previously reported by Hilbrands et al.4) both had partial/semi-lobar holoprosencephaly, while P03 has dysmorphic features which could be consistent with holoprosencephaly (prominent central incisors and occiput, highly arched palate, and low-set ears) but brain MRI was declined by his parents and the diagnosis could not therefore be confirmed. All three individuals had very low birth weight (Z-score < −2), likely due to insulin deficiency in the last trimester of pregnancy, when insulin is the main fetal growth factor. Consistent with insulin deficiency in utero, the three case subjects all developed diabetes very early (2/3 diagnosed at 1 day and 1 at 13 weeks). P01 and P02 also had gallbladder agenesis, a clinical feature frequently associated with pancreatic agenesis.

The DDD study5 has identified de novo CNOT1 variants in three individuals with developmental delay (two missense—p.Leu2323Phe and p.Arg623Trp—and a nonsense—p.Gln33∗—variant) but none of them had holoprosencephaly or diabetes. Since our three case subjects were all heterozygous for the same novel missense CNOT1 variant and none of the DDD participants with heterozygous de novo CNOT1 variants had pancreatic or neurological structural malformations, we hypothesized that a mutation-specific mechanism rather than loss of function was responsible for the phenotype seen in our case subjects. We therefore generated a mouse line harboring the Cnot1p.(Arg535Cys) mutation using CRISPR (Supplemental Subjects and Methods).

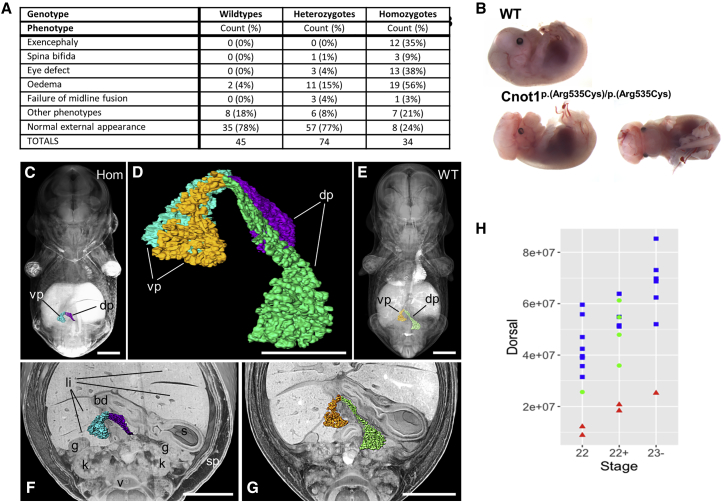

Heterozygous mice were born at a lower than expected frequency (Table S5), but without an obvious phenotype, while homozygosity for the mutation was embryonically lethal. At E14.5, embryos were still alive and present at expected Mendelian ratios and were therefore collected to assess their phenotype (Supplemental Subjects and Methods). Upon dissection, several gross morphological abnormalities were apparent in homozygotes, notably exencephaly, eye defects (mostly coloboma), and edema (Figures 2A, 2B, and S2; Table S6).

Figure 2.

Neurological and Pancreatic Abnormalities in Mouse Embryos Homozygous for the Cnot1 p.Arg535Cys Mutation

(A) Table listing the gross external phenotypes observed in E14.5 embryos. Numbers do not add to total as many embryos displayed multiple phenotypes. Significance by Fisher’s exact test, assuming an additive model. Exencephaly, p = 3.2 × 10−9; spina bifida, p = 0.027; eye defect, p = 5.5 × 10−8; edema, p = 2.6 × 10−7; midline defect, ns.

(B) Images showing representative E14.5 embryos: top shows wild-type embryo, bottom shows embryo homozygous for the CNOT1 p.Arg535Cys mutation with exencephaly and coloboma.

(C and E) Coronally sectioned, semi-transparent 3D volume models of stage-matched E14.5 embryos with superimposed models of the pancreas of homozygous (C) and wild-type (E) embryos.

(D) Overlay of extracted surface models of the pancreas of homozygous (blue, magenta) and wild-type embryos (orange, green).

(F and G) Coronally sectioned solid 3D volume rendered model of the abdomen of the embryos shown in (C) and (E) with superimposed pancreas. dp, dorsal pancreas; vp, ventral pancreas; li, liver lobes; s, stomach; sp, spleen; k, kidney; g, gonad; bd, bile duct.

Scale bars: 1,000 μm in (C), (E)–(G); 500 μm in (D).

(H) Graph showing the volume of the dorsal pancreas of E14.5 embryos in μm3. Blue squares show wild types, green circles are heterozygotes, and red triangles are homozygotes. Data analyzed using ANOVA with TukeyHSD posthoc test, effect of genotype p = 8.85 × 10−8; post hoc WT-Hom, p < 10−10; Het-Hom, p = 1.36 × 10−4, WT-Het, ns.

High-resolution episcopic microscopy (HREM) highlighted a significant reduction in the size of the pancreas in homozygous embryos in addition to several other abnormalities (Figures 2C–2G, Supplemental Subjects and Methods, DMDD website). The reduction in pancreatic size was found to be predominantly due to a smaller dorsal pancreas (Figures 2H and S3). These results provide compelling evidence for the role of Cnot1p.(Arg535Cys) in pancreatic development.

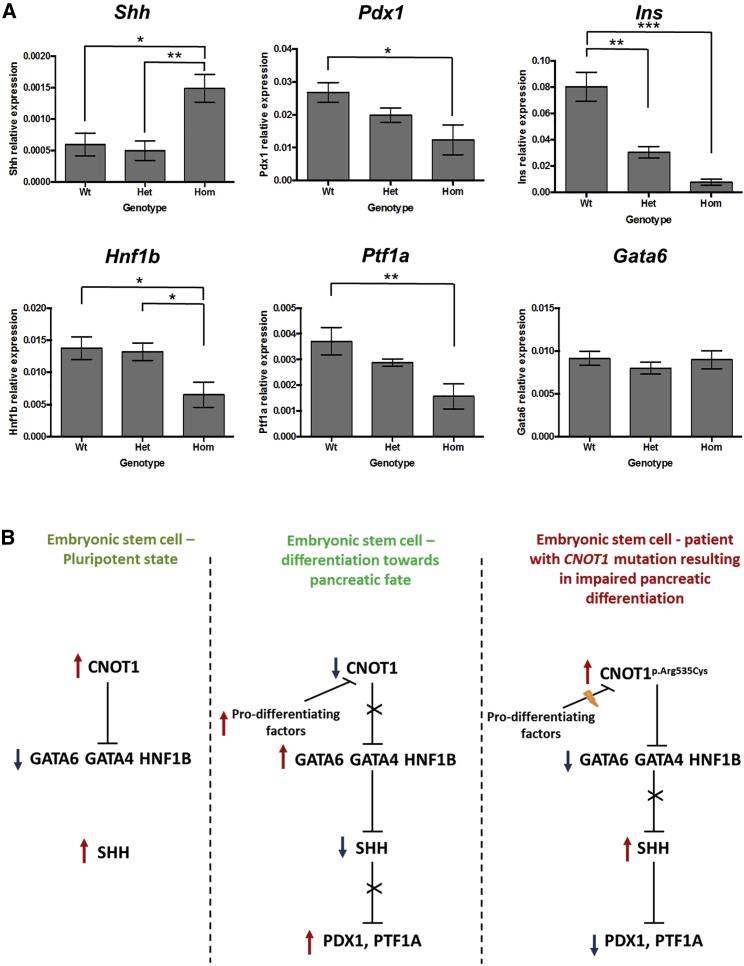

Expression analysis of pancreatic developmental factors on RNA extracted from pancreatic tissue in E14.5 wild-type, Cnot1p.(Arg535Cys)/p.(Arg535Cys), and Cnot1p.(Arg535Cys) embryos showed a significant increase of Shh expression in homozygous embryos, with decreased expression in Pdx1, Ins, Hnf1b, and Ptf1a (Figure 3A). No difference in expression was detected for Gata6 (Figure 3A) and Rxra (Figure S4).

Figure 3.

Expression Data and Possible Mechanism Involving CNOT1 in Pancreatic Development

(A) Graphs showing relative expression of genes in the pancreas of E14.5 embryos. Bars show mean ± SE. Data analyzed using ANOVA with TukeyHSD posthoc test. Results of posthoc tests shown on graphs, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Shh, effect of genotype p = 0.0107; Pdx1, effect of genotype p = 0.0189; Ins, effect of genotype p = 7.03 × 10−6; Hnf1b, effect of genotype p = 0.0294; Ptf1a, effect of genotype p = 0.00781; Gata6, effect of genotype p = ns. n = 4–12 animals per genotype.

(B) Schematic representation of the proposed role for CNOT1 in pancreatic development.

The pancreatic and neurological phenotypes observed in Cnot1p.(Arg535Cys)/p.(Arg535Cys) E14.5 mouse embryos are consistent with the pancreatic agenesis and holoprosencephaly observed in the three case subjects, confirming that the de novo CNOT1 mutation is indeed the cause of their disease. Mice required a homozygous mutation in Cnot1 to display a pancreatic and brain phenotype while a heterozygous CNOT1 mutation resulted in the phenotype in three individuals in our cohort. This has been described with other pancreatic developmental genes (e.g., HNF1B) and supports the hypothesis that the early stages of pancreatic development are not identical in mice and humans.6

The CNOT1 protein has not previously been suggested to have a role in pancreatic development; it is known to act both as scaffold of the CCR4-NOT complex and as an independent factor. As such, it mediates transcriptional repression7 and is expressed extremely early during embryonic development (E3.5 in the inner cell mass in mice8). In vitro studies have proposed that CNOT1 plays a critical role in maintaining human and mice embryonic stem cells in a pluripotent state by inhibiting primitive endoderm factors.8 CNOT1 expression peaks in undifferentiated human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells compared to subsequent stages of in vitro differentiation toward pancreatic endocrine cells,9 supporting its fundamental role in stem cells.

The increased expression of Shh in pancreatic tissue extracted from Cnot1p.(Arg535Cys)/p.(Arg535Cys) embryos would be consistent with a model in which the CNOT1 p.Arg535Cys mutation results in embryonic stem cells being maintained in an undifferentiated state through SHH-mediated inhibition of differentiation. SHH is a key developmental factor that is known to be crucial for pancreatic and brain development. Heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in SHH cause holoprosencephaly (MIM: 142945) and studies in both mouse and human embryos have shown that SHH expression needs to be repressed in the dorsal foregut endoderm for successful differentiation toward dorsal pancreas.6, 10 A recent study has suggested that the transcription factors Gata4 and Gata6 (mutations in which are a cause of pancreatic agenesis) regulate pancreatic endoderm identity by directly inhibiting Shh in mice.11 It is therefore possible that the p.Arg535Cys variant results in CNOT1 maintaining its inhibition activity on the GATA and other early differentiation factors and, as a consequence, SHH expression is not repressed (Figure 3B). Increased expression of Shh and decreased expression of Pdx1, Ins, Hnf1b, and Ptf1a detected in RNA extracted from pancreatic tissue in the E14.5 Cnot1p.(Arg535Cys)/p.(Arg535Cys) embryos would support this hypothesis. However, Gata4 expression could not be assessed as the assay specificity was too low and Gata6 expression was not found to be reduced. It is possible that Gata6 activity is actually inhibited earlier during development and then re-activated by a different pathway (Gata6 is needed for development of most endodermal-derived organs and heart) or could be inhibited by a different mechanism that does not result in reduced expression. The CNOT1 p.Arg535Cys mutation also affects neurological development in both our case subjects and mouse embryos. It is possible that this mutation results in ectopic SHH expression during brain development. This would be consistent with previous reports of Shh ectopic expression impairing midline development.12 Another possibility is that the effect of the CNOT1 mutation on SHH signaling differs between the brain and the pancreas, resulting in a reduced expression in the developing brain and increased expression during pancreatic development. Further experiments, ideally on younger embryos and human iPS cells, are needed in order to elucidate the mechanism by which the CNOT1 p.Arg535Cys mutation results in impaired pancreatic and neurological development.

Our study identifies a spontaneous CNOT1 p.Arg535Cys mutation as the genetic cause of a rare syndrome of pancreatic agenesis and holoprosencephaly, highlighting a previously unsuspected role of CNOT1 as a key factor in both pancreatic and neurological development. This is the 7th gene causative of pancreatic agenesis described so far and the first pancreatic agenesis gene that is thought to be important for maintaining stem cells’ pluripotency. These findings suggest a new mechanism by which impairment of the very early stages of development result in pancreatic agenesis and abnormal brain development.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families for participating in this study. We are grateful to Anna-Marie Johnson and Benjamin Bunce for their technical assistance and to Dr. Jane Ferguson and Dr. Joerg Detlev Moritz for assistance with the MRI images. We are grateful to Emma Siragher and Monika Dabrowska for assistance with embryo dissection, Antonella Galli for advice on embryo work, members of the DMDD consortium at the Francis Crick Institute for imaging the embryos, Julia Rose for assistance with HREM image analysis, members of the Research Support Facility and Mouse Pipelines at the Wellcome Sanger Institute for mouse management and husbandry, Rachel Moore and Eleanor Wheeler for help with the mouse statistical analysis, Bill Bottomley for help with mouse generation, and Elizabeth Wynn for help with genotyping. We would also like to thank Prof. Lori Sussell for useful discussion on the SHH pathway.

I.B. is funded by Wellcome (WT206194). A.T.H. and S.E. are the recipients of a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator award (grant WT098395/Z/12/Z) and A.T.H. is employed as a core member of staff within the NIHR funded Exeter Clinical Research Facility and is an NIHR senior investigator. E.D.F. was a Naomi Berrie Fellow in Diabetes Research (grant 50565) during the study. S.E.F. has a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (grant number 105636/Z/14/Z). C.C.W. holds a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship (grant number 105914/Z/14/Z). H.H. is funded by the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO), the VUB Research Council, and Stichting Diabetes Onderzoek Nederland.

Published: April 18, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Data can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.03.018.

Contributor Information

Andrew T. Hattersley, Email: a.t.hattersley@exeter.ac.uk.

Inês Barroso, Email: ines.barroso@mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk.

Web Resources

DECIPHER, https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/

DMDD, https://dmdd.org.uk

gnomAD Browser, https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.De Franco E., Ellard S. Genome, exome, and targeted next-generation sequencing in neonatal diabetes. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2015;62:1037–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen H.L., Flanagan S.E., Shaw-Smith C., De Franco E., Akerman I., Caswell R., Ferrer J., Hattersley A.T., Ellard S., International Pancreatic Agenesis Consortium GATA6 haploinsufficiency causes pancreatic agenesis in humans. Nat. Genet. 2011;44:20–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrisey E.E., Tang Z., Sigrist K., Lu M.M., Jiang F., Ip H.S., Parmacek M.S. GATA6 regulates HNF4 and is required for differentiation of visceral endoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3579–3590. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilbrands R., Keymolen K., Michotte A., Marichal M., Cools F., Goossens A., Veld P.I., De Schepper J., Hattersley A., Heimberg H. Pancreas and gallbladder agenesis in a newborn with semilobar holoprosencephaly, a case report. BMC Med. Genet. 2017;18:57. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0419-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firth H.V., Wright C.F., DDD Study The Deciphering Developmental Disorders (DDD) study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011;53:702–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jennings R.E., Berry A.A., Kirkwood-Wilson R., Roberts N.A., Hearn T., Salisbury R.J., Blaylock J., Piper Hanley K., Hanley N.A. Development of the human pancreas from foregut to endocrine commitment. Diabetes. 2013;62:3514–3522. doi: 10.2337/db12-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler G.S., Mulder K.W., Bardwell V.J., Kalkhoven E., Timmers H.T. Human Ccr4-Not complex is a ligand-dependent repressor of nuclear receptor-mediated transcription. EMBO J. 2006;25:3089–3099. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng X., Dumitru R., Lackford B.L., Freudenberg J.M., Singh A.P., Archer T.K., Jothi R., Hu G. Cnot1, Cnot2, and Cnot3 maintain mouse and human ESC identity and inhibit extraembryonic differentiation. Stem Cells. 2012;30:910–922. doi: 10.1002/stem.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Bunt M., Lako M., Barrett A., Gloyn A.L., Hansson M., McCarthy M.I., Beer N.L., Honoré C. Insights into islet development and biology through characterization of a human iPSC-derived endocrine pancreas model. Islets. 2016;8:83–95. doi: 10.1080/19382014.2016.1182276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apelqvist A., Ahlgren U., Edlund H. Sonic hedgehog directs specialised mesoderm differentiation in the intestine and pancreas. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:801–804. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xuan S., Sussel L. GATA4 and GATA6 regulate pancreatic endoderm identity through inhibition of hedgehog signaling. Development. 2016;143:780–786. doi: 10.1242/dev.127217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang X., Litingtung Y., Chiang C. Ectopic sonic hedgehog signaling impairs telencephalic dorsal midline development: implication for human holoprosencephaly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:1454–1468. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.