Key Points

Question

Are brain atrophy and/or masseter sarcopenia associated with mortality after traumatic injury in adults older than 65 years?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study of 327 adults 65 years and older, both brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia conferred independent increased hazards of death within 1 year of traumatic injury, after adjustment for age, comorbidity, clinical course, and injury characteristics.

Meaning

Brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia may be prognostic indicators in older adults affected by trauma, which could be used to guide targeted interventions.

This cohort study uses opportunistic computed tomography imaging to investigate the association of masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy with 1-year mortality among elderly patients who have sustained trauma.

Abstract

Importance

Older adults are disproportionately affected by trauma and accounted for 47% of trauma fatalities in 2016. In many populations and disease processes, described risk factors for poor clinical outcomes include sarcopenia and brain atrophy, but these remain to be fully characterized in older trauma patients. Sarcopenia and brain atrophy may be opportunistically evaluated via head computed tomography, which is often performed during the initial trauma evaluation.

Objective

To investigate the association of masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy with 1-year mortality among trauma patients older than 65 years by using opportunistic computed tomography imaging.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in a level 1 trauma center from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2014, with a 1-year follow-up to assess mortality. Washington state residents 65 years or older who were admitted to the trauma intensive care unit with a head Abbreviated Injury Scale score of less than 3 were eligible. Patients with incomplete data and death within 1 day of admission were excluded. Data analysis was completed from June 2017 to October 2018.

Exposures

Masseter muscle cross-sectional area and brain atrophy index were measured using a standard clinical Picture Archiving and Communication System application to assess for sarcopenia and brain atrophy, respectively.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was 1-year mortality. Secondary outcomes were discharge disposition and 30-day mortality.

Results

The study cohort included 327 patients; 72 (22.0%) had sarcopenia only, 71 (21.7%) had brain atrophy only, 92 (28.1%) had both, and 92 (28.1%) had neither. The mean (SD) age was 77.8 (8.6) years, and 159 patients (48.6%) were women. After adjustment for age, comorbidity, complications, and injury characteristics, masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy were both independently and cumulatively associated with mortality (masseter muscle cross-sectional area per SD less than the mean: hazard ratio, 2.0 [95% CI, 1.2-3.1]; P = .005; brain atrophy index per SD greater than the mean: hazard ratio, 2.0 [95% CI, 1.1-3.5]; P = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

Masseter muscle sarcopenia and brain atrophy were independently and cumulatively associated with 1-year mortality in older trauma patients after adjustment for other clinical factors. These radiologic indicators are easily measured opportunistically through standard imaging software. The results can potentially guide conversations regarding prognosis and interventions with patients and their families.

Introduction

In 2016, older adults accounted for 31% of trauma incidents and 47% of trauma-associated deaths in the United States.1 Additionally, older adults who survive acute hospitalization are more likely to be discharged to nonindependent living facilities.2,3 Multiple investigations have identified frailty, a geriatric syndrome generally defined by loss of physiologic reserve,4,5,6 as a contributing factor in adverse outcomes in older trauma patients.7,8,9,10 National guidelines from multiple collaborative organizations, including the American Geriatrics Society, American College of Surgeons, and American College of Emergency Medicine, recommend frailty screening in preoperative and emergency settings alike.11,12 Yet, there is no universally agreed-on frailty assessment tool to establish the diagnosis in the trauma setting, in which checklists, questionnaires, or functional tests are often not practical.4,13 Given the multidimensional nature of frailty and its implications for older adults who sustain trauma, a significant void in pragmatic, rapid, and actionable assessment for this population remains.

Recently, radiologic indicators of frailty have emerged as potential surrogate measurements of physical frailty in the trauma setting.14,15,16 Sarcopenia, defined as low muscle mass along with either low strength or function, is closely associated with frailty17,18,19 and independently associated with poor outcomes in trauma patients.15,20,21,22 Sarcopenia can be evaluated opportunistically using chest and abdominopelvic computed tomographic (CT) scans during the initial trauma workup, but this modality is limited because body imaging is often not obtained in older trauma patients. Older patients frequently sustain low-velocity mechanisms of injury (such as ground-level falls), which are less prone to visceral injury and do not prompt an extensive traumatic workup. In contrast, head CTs are commonly ordered in older patients because of the increased risk for intracranial hemorrhage after even low-level trauma.23 Opportunistic sarcopenia assessment in the trauma-affected population was recently expanded to head CT by examining masseter cross-sectional area (MCSA), where lower values correlated with abdominal muscle sarcopenia and were also associated with an increased risk of 2-year mortality.14

Similar to the association between aging and sarcopenia, cellular changes occur in the aging brain, including atrophy.24 Brain atrophy accelerates with aging and has been traditionally determined through brain volume measurement.25 However, this technique is time consuming and often requires specialized software; thus, it is impractical as a rapid screening tool in trauma.

In contrast, the bicaudate index or bicaudate ratio is a measure of subcortical brain atrophy that can be measured readily on head CT using standard clinical imaging software.26,27 In a recent 2018 analysis of a prospective 10-year outpatient cohort of more than 1500 patients, incremental increases in physical frailty were associated with increased probability of brain atrophy.28 Indeed, brain atrophy measured opportunistically via head CT may offer additional prognostic information, much like measures of skeletal muscle. We hypothesize that (1) brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia are independently associated with 1-year mortality in older patients with trauma and (2) the combination of brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia confers an additive mortality risk in this population.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

In this retrospective cohort study, the Washington state trauma registry and institutional medical record were used to identify patients 65 years or older who were admitted to the Harborview Medical Center trauma intensive care unit (ICU) from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2014, who survived the first 24 hours of admission, were Washington state residents, and had a high-quality head CT within 7 days of admission. To minimize measurement and outcome biases in patients with severe intracranial injuries, patients with a head Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or greater were not included. Entry criteria focused on (1) patients in the ICU, because they were more likely to undergo head CT; and (2) Washington state residents, because mortality data are readily available for them. Patients with missing data were excluded. Harborview Medical Center serves as the only level 1 trauma center for Washington, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho.

This study received institutional review board approval with waiver of informed consent by the University of Washington. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines were used in all phases of this study.29

Exposure Variables

Brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia were the primary exposure variables, measured using brain atrophy index (BAI) and masseter cross-sectional area (MCSA). The BAI, also referred to as the bicaudate ratio or bicaudate index, represents the ratio of intercaudate distance to interskull distance. Higher ratios indicate more atrophy. Mean MCSA was calculated as the mean of both masseter muscles. If one masseter muscle could not be analyzed, only a single MCSA measure was used.

Given the absence of defined diagnostic thresholds for brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia, sex-specific cohort medians were chosen for dichotomization. The cohort was divided into 4 groups for univariate comparisons: patients with both masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy, those with brain atrophy only, those with masseter sarcopenia only, and those with neither condition. Patients in whom both MCSA and BAI could not be assessed were excluded from the analysis.

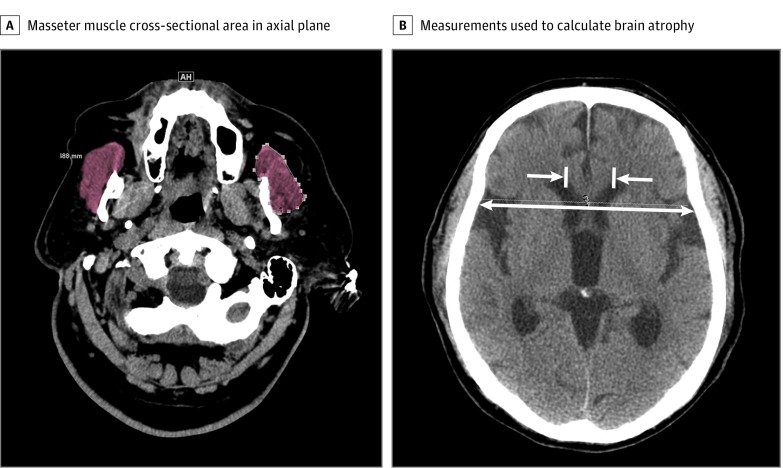

Radiologic Measurement Protocol

The base of the zygomatic arch was identified in each patient in the coronal plane. The MCSA measurements were taken at 2 cm below the zygomatic arch in the axial plane.14 The BAI measurements were performed at the level of the fornix apex, which was identified in the coronal plane. To calculate BAI, intercaudate distance was divided by interskull distance. Figure 1 demonstrates examples of these measurements. All images were analyzed using tools native to the institution’s standard clinical Picture Archiving and Communication System application. Repeated measures and parallel measures among 2 trained imaging evaluators (C.T. and S.J.K.) confirmed good to excellent intraclass correlation coefficients (MCSA, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.85-0.98]; P < .001; BAI, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.92-0.99]; P < .001).

Figure 1. Example Masseter and Brain Atrophy Index Measurements.

A, Measurement of masseter muscle cross-sectional area in the axial plan, 2 cm below the inferior edge of the zygomatic arch. The masseter is highlighted in brown. B, Measurements taken to calculate brain atrophy index (intercaudate distance divided by interskull distance in the axial plane at the level of the fornix). The 2 medial-facing arrows show the caudate (intercaudate distance). The longer, double-arrow line shows the interskull distance, which is measured at the same coronal plane as the intercaudate distance.

Covariates

Demographics, clinical data, and injury characteristics were examined in this analysis, including age, sex, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), updated Charlson Comorbidity Index scores, mechanism of injury, Injury Severity Score, Abbreviated Injury Scale scores, ventilator requirement, ICU length of stay, in-hospital complications, and need for operative intervention, among other variables. Age and body mass index were treated as continuous variables. Charlson Comorbidity Index, Injury Severity Score, and Abbreviated Injury Scale scores were treated as discrete variables.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause 1-year mortality after hospital discharge. Discharge disposition was examined as a secondary outcome because trauma patients who are discharged to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) experience higher readmission rates, have higher 30-day mortality, and often never return home.30,31,32 Categories included discharge to home or home with home health, discharge to an inpatient rehabilitation unit, discharge to an SNF/long-term acute care (LTAC) facility, and in-hospital death. Discharge to an SNF/LTAC or in-hospital death vs any other disposition was collapsed into a dichotomous variable called unfavorable discharge. All-cause 30-day mortality was also examined as a secondary outcome. Mortality data were obtained from the Washington State Department of Health.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as medians with interquartile range for noncategorical variables and as counts with frequencies for categorical variables. The Kruskal-Wallis test with the Dunn post hoc test and the Šídák correction for multiple comparisons were used for noncategorical univariate comparisons. The Fisher exact test was used for categorical comparisons. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were created to describe 1-year survival after discharge for median-based groups. The log-rank test with the Bonferroni correction was used for comparisons among all 4 groups and between 2 groups. Hypothesis testing was only performed for the primary and secondary outcomes.

Unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models were designed to assess variable associations with 1-year mortality. For these regression models, MCSA and BAI variables were standardized to a mean value of 0 and an SD of 1. Variables with known clinical influence and those that approached significance (P ≤ .20) were included in the adjusted model. Interaction variables were tested based on bivariate correlations. Individual variable P values and both Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria were used to guide model optimization. Postestimation model fit and assumption confirmations were performed. Patients with missing data were excluded from analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted with Stata/SE version 14.2 (StataCorp) using an a priori 2-sided significance level of P < .05.

Results

Three hundred sixty-four patients were identified from the trauma registry and medical records as eligible for the study because they had a head CT of acceptable quality. Thirty-seven were excluded because of missing data (n = 24) or death within 1 day of admission (n = 13). The remaining 327 made up the cohort. The mean (SD) age was 77.8 (8.6) years, and 159 patients (48.6%) were women.

The sex-specific mean (SD) MCSAs were 347.8 (87.5) mm2 for female patients and 438.6 (100.2) mm2 for male patients; corresponding median thresholds were 339.1 mm2 and 427.2 mm2, respectively. The mean (SD) BAIs were 0.139 (0.030) for female patients and 0.144 (0.027) for male patients; median values were 0.136 and 0.138, respectively. Based on these parameters, the cohort was divided into 4 groups: 92 individuals (28.1%) with masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy, 72 (22.0%) with masseter sarcopenia only, 71 (21.7%) with brain atrophy only, and 92 (28.1%) with neither condition. The overall flowchart of patient inclusion, exclusion, and group assignment is depicted in the eFigure in the Supplement. Patient demographics, clinical data, and injury characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Sarcopenia or Brain Atrophy (n = 92) | Masseter Sarcopenia Only (n = 72) | Brain Atrophy Only (n = 71) | Both Sarcopenia and Brain Atrophy (n = 92) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 73 (68-80) | 74 (70-82) | 80 (73-86) | 82 (75-86) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 51 (55.4) | 33 (45.8) | 33 (46.5) | 51 (55.4) |

| Female | 41 (44.6) | 39 (54.2) | 38 (53.5) | 41 (44.6) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 27 (23-31) | 27 (23-29) | 26 (22-29) | 25 (22-29) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, median (IQR) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) |

| Type of injury | ||||

| Fall | 45 (48.9) | 32 (44.4) | 26 (36.6) | 24 (26.1) |

| Blunt trauma (other than fall) | 45 (48.9) | 38 (52.8) | 43 (60.6) | 64 (69.6) |

| Penetrating injury | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Other | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | 3 (3.3) |

| Injury Severity Score, median (IQR) | 14 (9-17) | 12 (9-17) | 11 (6-17) | 10 (6-17) |

| Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale score, median (IQR) | ||||

| Head | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) |

| Chest | 2 (0-3) | 2 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) |

| Spine | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) |

| Ever ventilated | 21 (22.8) | 17 (23.6) | 16 (22.5) | 20 (21.7) |

| Operative management | 39 (42.4) | 31 (43.1) | 33 (46.5) | 34 (37.0) |

| Any in-hospital complication | 10 (10.9) | 19 (26.4) | 8 (11.3) | 18 (19.6) |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | ||||

| Intensive care unit | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-5) | 2 (1-5) | 2 (1-5) |

| Hospital | 6 (4-9) | 7 (5-11) | 6 (4-11) | 7 (4-11) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); IQR, interquartile range.

Univariate comparisons among groups are shown in Table 2. There were significant differences in discharge disposition among groups, with a greater proportion of SNF and LTAC discharges among patients with brain atrophy or masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy compared with those with neither condition. Patients with brain atrophy with or without sarcopenia were also more likely to be discharged to an SNF or LTAC or experience in-hospital death compared with those with neither condition (patients with masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy: relative risk, 1.7 [95% CI, 1.3-2.3]; P = .002; patients with brain atrophy only: relative risk, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.2-2.2]; P = .01).

Table 2. Outcomes Among Groups With Masseter Sarcopenia and Brain Atrophy.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Sarcopenia or Brain Atrophy (n = 92) | Masseter Sarcopenia Only (n = 72) | Brain Atrophy Only (n = 71) | Both Sarcopenia and Brain Atrophy (n = 92) | ||

| Disposition | |||||

| Home or home with home health | 48 (52.2) | 31 (43.1) | 26 (36.6) | 30 (32.6) | <.001a |

| Inpatient rehab | 8 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| SNF/LTAC | 31 (33.7) | 32 (44.4) | 41 (57.8) | 53 (57.6) | |

| In-hospital death | 5 (5.4) | 9 (12.5) | 4 (5.6) | 8 (8.7) | |

| Unfavorable dispositionb | 36 (39.1) | 41 (56.9) | 45 (63.4) | 61 (66.3) | .001a |

| Death within 30 d of injury | 5 (5.4) | 6 (8.5) | 9 (12.5) | 14 (15.2) | .14 |

| Death within 1 y of injury | 8 (8.7) | 12 (16.9) | 12 (16.7) | 25 (27.2) | .01c |

Abbreviations: LTAC, long-term acute care facility; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

After correction for multiple comparisons, only pairwise comparisons between patients with no sarcopenia or brain atrophy and patients with brain atrophy and between patients with neither sarcopenia nor brain atrophy and those with both sarcopenia and brain atrophy were significant.

Defined as a discharge to an SNF or LTAC or death.

After correction for multiple comparisons, only the difference between patients with neither sarcopenia nor brain atrophy and those with both sarcopenia and brain atrophy was significant.

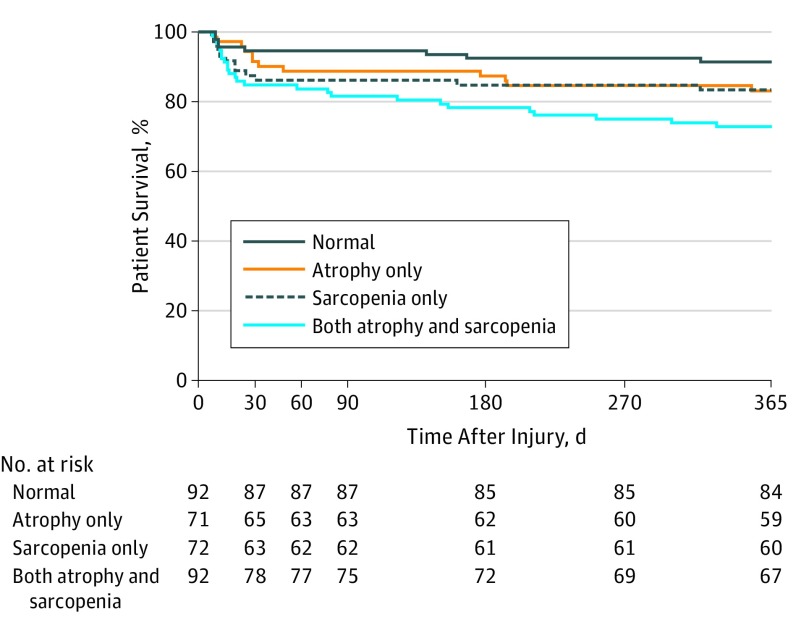

Mortality After Injury

There was no difference in 30-day mortality among the 4 groups. However, a significant result was observed in 1-year mortality (χ23 = 10.99; P = .01), with a significant difference between patients with masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy vs patients with neither condition after adjustment for multiple comparisons (relative risk ratio, 3.1 [95% CI, 1.5-6.6]). Mortality among groups was plotted over time on a Kaplan-Meier survival curve (Figure 2). While the overall log-rank comparison among groups was significant (χ23 = 10.86; P = .01), after adjustment for multiple comparisons, only the comparison of patients with masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy with patients with neither condition remained significant (χ21 = 10.45; P = .001).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Estimates.

Patients were divided into 4 groups based on the median masseter cross-sectional area and brain atrophy index. Overall log-rank outcome was χ23 = 10.86 (P = .01). Pairwise comparison log-rank P values were adjusted with Bonferroni correction (patients with both conditions vs patients with neither condition, χ21 = 10.45; P = .007; patients with brain atrophy only vs patients with neither condition, χ21 = 2.39; P = .72; patients with masseter sarcopenia only vs patients with neither condition, χ21 = 2.45; P = .71; patients with brain atrophy vs patients with masseter sarcopenia, χ21 = 0.00; P > .99; patients with both conditions vs patients with brain atrophy only, χ21 = 2.52; P = .68; patients with both conditions vs patients with masseter sarcopenia only, χ21 = 2.27; P = .79).

Both unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for 1-year mortality were calculated for sarcopenia, brain atrophy, and other variables of interest (Table 3). As with the Fisher exact and log-rank tests, unadjusted HRs showed a significant association with 1-year mortality only between patients with masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy and patients with neither condition (HR, 3.4 [95% CI, 1.5-7.6]; P = .002).

Table 3. Risk of 1-Year Mortality in Unadjusted and Adjusted Survival Models.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Indicator | ||||

| No sarcopenia or atrophy | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA |

| Sarcopenia only | 2.0 (0.8-4.8) | .13 | NA | NA |

| Atrophy only | 2.0 (0.8-5.0) | .12 | NA | NA |

| Sarcopenia and atrophy | 3.4 (1.5-7.6) | .002 | NA | NA |

| Brain atrophy index, per SD greater than mean | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | <.001 | 2.0 (1.1-3.5) | .02 |

| Masseter cross-sectional area, per SD less than mean | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | .001 | 2.0 (1.2-3.1) | .005 |

| Age, per decade older than 65 y | 2.1 (1.5-2.7) | <.001 | 1.9 (1.3-2.7) | .001 |

| Male | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) | .89 | NA | NA |

| BMI, per unit | 1.0 (0.9-1.0) | .37 | NA | NA |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, per point | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | <.001 | 1.4 (1.3-1.6) | <.001 |

| Fall injury mechanism | 2.7 (1.5-5.0) | .002 | 2.1 (1.1-4.4) | .04 |

| Injury Severity Score, per point | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .48 | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | .004 |

| Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale score, per point | ||||

| Head | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | .13 | NA | NA |

| Chest | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | .06 | NA | NA |

| Spine | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .08 | NA | NA |

| Ever ventilated | 3.3 (1.9-5.6) | <.001 | NA | NA |

| Operative management | 1.6 (1.0-2.7) | .06 | NA | NA |

| Any in-hospital complication | 2.2 (1.2-3.9) | .009 | 1.9 (1.0-3.6) | .048 |

| Length of stay, per d | ||||

| Intensive care unit | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | .03 | NA | NA |

| Hospital | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .05 | NA | NA |

| Discharge to SNF/LTACa | 3.5 (1.5-8.1) | .003 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); LTAC, long-term acute care facility; NA, not applicable; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Among the 301 patients who survived to discharge. This variable is excluded from the adjusted analysis to include patients who did not survive to discharge in the final model.

However, when MCSA and BAI were standardized and treated as continuous variables, associations with 1-year mortality were both significant (MCSA per SD less than the mean: HR, 1.7 [95% CI, 1.2-2.4]; P = .001; BAI per SD greater than the mean: HR, 1.5 [95% CI, 1.2-1.8]; P < .001). Older age (per decade older than 65 years; HR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.5-2.7]; P < .001), higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (HR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.3-1.5]; P < .001), fall injury mechanism (HR, 2.7 [95% CI, 1.5-5.0]; P = .002), in-hospital ventilator requirement (HR, 3.3 [95% CI, 1.9-5.6]; P < .001), in-hospital complication (HR, 2.2 [95% CI, 1.2-3.9]; P = .009), longer ICU length of stay (per day; HR, 1.0 [95% CI, 1.0-1.1]; P = .03), and discharge to an SNF or LTAC (HR, 3.5 [95% CI, 1.5-8.1]; P = .003) were also all significantly associated with increased hazards of 1-year mortality.

In the adjusted Cox proportional hazards model, both MCSA and BAI remained significantly and independently associated with 1-year mortality (MCSA per SD less than the mean: HR, 2.0 [95% CI, 1.2-3.1]; P = .005; BAI per SD greater than the mean: HR, 2.0 [95% CI, 1.1-3.5]; P = .02). Charlson Comorbidity Index (HR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.3-1.6]; P < .001) and fall injury (HR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.1-4.4]; P = .04), and presence of any complication (HR, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.0-3.6]; P = .048) remained associated. Additionally, Injury Severity Score (per point; HR, 1.0 [95% CI, 1.0-1.1]; P = .004) emerged as a minor but significant variable after adjustment.

Discussion

We investigated the use of MCSA and BAI as factors associated with 1-year all-cause mortality after traumatic injury in older adults. The survival distributions of patients who were determined to have both masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy differed significantly from patients who had neither. After adjusting for covariates and interactions, both masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy were significantly and independently associated with mortality in an additive fashion. Few studies have examined the implications of masseter sarcopenia in trauma patients, and to our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between brain atrophy and mortality in any surgical population.

The strong associations of frailty, sarcopenia, and other indicators of vulnerability with poor clinical outcomes in patients with trauma lends a rationale for continued development of reliable, objective, and clinically useful assessment instruments. Assessment of this population is of particular importance given their unique, unplanned presentation and often volatile clinical status. In this context, the advantage of using MCSA and BAI lies in the relatively high frequency of trauma-associated head CT acquisition. In our institution, more than 50% of trauma patients 65 years and older undergo head CT, compared with less than 30% for abdominopelvic CT. Brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia are clearly associated with patient disposition and 1-year mortality. This study did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with 30-day mortality, as others have16; however, the tendency toward an escalating proportion of death at 30 days with each indicator is apparent.

While sarcopenia can also be assessed via head CT using the temporalis muscle, the masseter muscle is the major muscle of mastication that may be associated with nutrition33 and is correlated with abdominal sarcopenia.14 Masseter muscle mass and function have been used as a correlate to total body skeletal muscle mass in older adults.34,35 It is possible that the same mechanisms that lead to a loss of skeletal muscle mass also act on the masseter muscle.

A key aspect of this study was that measurements were taken using the standard Picture Archiving and Communication System application used at our institution. This demonstrates the potential for ready, pragmatic translation to a clinical environment without the need for specialized software or arduous image analysis.

The implications of early identification of vulnerable trauma patients are several. In another study,36 an age-based protocol for automatic geriatrician consultation in trauma patients 70 years and older resulted in improved advance care planning and increased multidisciplinary care. In the ICU, advanced care planning reduces readmission and length of stay.37 Other improvements in outcomes for vulnerable patients undergoing surgery have come in the form of prehabilitation,38 which is not possible in the trauma population. However, postoperative exercise therapy is associated with improvements in functional outcomes and quality of life for frail patients undergoing elective surgery.39 Early mobilization in a medical ICU setting improves functional outcomes as well.40 While older trauma patients differ from those having elective surgeries or those in the medical ICU, it is reasonable to test the potential of targeted interventions in this high-risk population. It is also worth noting that geriatricians, therapists, and other consultants (including those in palliative medicine) are finite resources. Consequently, a resource-sensitive approach might identify vulnerable patients, such as those with sarcopenia and/or brain atrophy, to assess whether these interventions are effective. Relevant outcomes would include improved coordination of care, multidisciplinary decision-making, decreased length of stay, morbidity, and mortality. Most importantly, interventions that target a subgroup of older patients that could benefit most should measure improvements in quality of life and functional status after discharge.

Limitations

The population of the study consists only of trauma patients from Harborview Medical Center, a level 1 trauma center that also serves as the county’s safety net hospital. While the study population does reflect the general demographics of Washington state and the Pacific Northwest, the use of a single institution limits the generalizability of the results. The inclusion criteria required a head CT image that was acceptable for analysis of both BAI and MCSA. A next step would be to relax exclusion criteria for image quality and keep patients in whom only one indicator could be measured. Finally, the retrospective observational design is subject to selection bias and limits the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

In this retrospective cohort study, we found that masseter sarcopenia and brain atrophy, as measured by masseter cross-sectional area and brain atrophy index, were independently associated with increased 1-year mortality in older trauma patients after adjustment for age, comorbidity, and injury characteristics. Furthermore, the combination of both brain atrophy and masseter sarcopenia conferred an additive mortality risk in this cohort. Both measurements can be opportunistically obtained from routine head CT. These measurements can potentially be evaluated as predictors of postdischarge outcomes and methods to identify patients who would benefit from interventions.

eFigure. Study flow diagram.

References

- 1.American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank 2016 Annual Report. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/trauma/ntdb/ntdb%20annual%20report%202016.ashx. Published 2016. Accessed August 3, 2018.

- 2.Richmond TS, Kauder D, Strumpf N, Meredith T. Characteristics and outcomes of serious traumatic injury in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):215-222. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashmi A, Ibrahim-Zada I, Rhee P, et al. Predictors of mortality in geriatric trauma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(3):894-901. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182ab0763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392-397. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489-495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Cawthon PM, et al. ; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group . A comparison of frailty indexes for the prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and mortality in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):492-498. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02137.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):382-389. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fawcett VJ, Flynn-O’Brien KT, Shorter Z, et al. Risk factors for unplanned readmissions in older adult trauma patients in Washington State: a competing risk analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(3):330-338. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, et al. Superiority of frailty over age in predicting outcomes among geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(8):766-772. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohanty S, Rosenthal RA, Russell MM, Neuman MD, Ko CY, Esnaola NF. Optimal Perioperative Management of the Geriatric Patient: A Best Practices Guideline from the American College of Surgeons NSQIP and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(5):930-947. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Emergency Physicians; American Geriatrics Society; Emergency Nurses Association; Society for Academic Emergency Medicine; Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines Task Force . Geriatric emergency department guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(5):e7-e25. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald VS, Thompson KA, Lewis PR, Sise CB, Sise MJ, Shackford SR. Frailty in trauma: A systematic review of the surgical literature for clinical assessment tools. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(5):824-834. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace JD, Calvo RY, Lewis PR, et al. Sarcopenia as a predictor of mortality in elderly blunt trauma patients: Comparing the masseter to the psoas using computed tomography. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(1):65-72. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairchild B, Webb TP, Xiang Q, Tarima S, Brasel KJ. Sarcopenia and frailty in elderly trauma patients. World J Surg. 2015;39(2):373-379. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2785-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu P, Uhlich R, White J, Kerby J, Bosarge P. Sarcopenia measured using masseter area predicts early mortality following severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(20):2400-2406. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landi F, Calvani R, Cesari M, et al. Sarcopenia as the biological substrate of physical frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(3):367-374. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bales CW, Ritchie CS. Sarcopenia, weight loss, and nutritional frailty in the elderly. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:309-323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morley JE, von Haehling S, Anker SD, Vellas B. From sarcopenia to frailty: a road less traveled. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2014;5(1):5-8. doi: 10.1007/s13539-014-0132-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeAndrade J, Pedersen M, Garcia L, Nau P. Sarcopenia is a risk factor for complications and an independent predictor of hospital length of stay in trauma patients. J Surg Res. 2018;221:161-166. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moisey LL, Mourtzakis M, Cotton BA, et al. ; Nutrition and Rehabilitation Investigators Consortium (NUTRIC) . Skeletal muscle predicts ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, and mortality in elderly ICU patients. Crit Care. 2013;17(5):R206. doi: 10.1186/cc12901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan SJ, Pham TN, Arbabi S, et al. Association of radiologic indicators of frailty with 1-year mortality in older trauma patients: opportunistic screening for sarcopenia and osteopenia. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):e164604. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandstrom CK, Nunez DB. Head and neck injuries: special considerations in the elderly patient. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2018;28(3):471-481. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo H, Siu W, D’Arcy RC, et al. MRI assessment of whole-brain structural changes in aging. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1251-1270. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S139515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opfer R, Ostwaldt AC, Sormani MP, et al. Estimates of age-dependent cutoffs for pathological brain volume loss using SIENA/FSL-a longitudinal brain volumetry study in healthy adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;65:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bermel RA, Bakshi R, Tjoa C, Puli SR, Jacobs L. Bicaudate ratio as a magnetic resonance imaging marker of brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(2):275-280. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.2.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma J, Sanfilipo MP, Benedict RH, Weinstock-Guttman B, Munschauer FE III, Bakshi R. Whole-brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis measured by automated versus semiautomated MR imaging segmentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(6):985-996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallucci M, Piovesan C, Di Battista ME. Associations between the frailty index and brain atrophy: the Treviso Dementia (TREDEM) registry. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(4):1623-1634. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hakkarainen TW, Arbabi S, Willis MM, Davidson GH, Flum DR. Outcomes of patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities after acute care hospitalizations. Ann Surg. 2016;263(2):280-285. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A, et al. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(8):1105-1122. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4867-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1542-1551. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaszynska E, Godala M, Szatko F, Gaszynski T. Masseter muscle tension, chewing ability, and selected parameters of physical fitness in elderly care home residents in Lodz, Poland. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1197-1203. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S66672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umeki K, Watanabe Y, Hirano H. Relationship between masseter muscle thickness and skeletal muscle mass in elderly persons requiring nursing care in north east Japan. International Journal of Oral-Medical Sciences. 2017;15(3-4):152-159. doi: 10.5466/ijoms.15.152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umeki K, Watanabe Y, Hirano H, et al. The relationship between masseter muscle thickness and appendicular skeletal muscle mass in Japanese community-dwelling elders: A cross-sectional study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:18-22. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olufajo OA, Tulebaev S, Javedan H, et al. Integrating geriatric consults into routine care of older trauma patients: one-year experience of a level I trauma center. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(6):1029-1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khandelwal N, Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Coe NB, Long AC, Curtis JR. Estimating the effect of palliative care interventions and advance care planning on ICU utilization: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1102-1111. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barberan-Garcia A, Ubré M, Roca J, et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267(1):50-56. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIsaac DI, Jen T, Mookerji N, Patel A, Lalu MM. Interventions to improve the outcomes of frail people having surgery: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0190071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874-1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Study flow diagram.