Abstract

Fish oil, rich in the very-long chain omega (ω)-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), has been found to have immunomodulatory effects in different groups of critically ill patients. In addition, its parenteral administration seems to attenuate the inflammatory response within 2 to 3 days. The activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway has been suggested to mediate such immunoregulatory effects. As different experimental studies have convincingly illustrated that enhanced vagal tone can decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, novel monitoring tools of its activity at the bedside could be developed, to evaluate nutritional manipulation of immune response in the critically ill. Heart rate variability (HRV) is the variability of R-R series in the electrocardiogram and could be a promising surrogate marker of immune response and its modulation during fish oil feeding, rich in ω-3 PUFAs. Heart rate variability is an indirect measure of autonomic nervous system (ANS) output, reflecting mainly fluctuations in ANS activity. Through HRV analysis, different “physiomarkers” can be estimated that could be used as early and more accurate “smart alarms” because they are based on high-frequency measurements and are much more easy to get at the bedside. On the contrary, various “biomarkers” such as cytokines exhibit marked interdependence, pleiotropy, and their plasma concentrations fluctuate from day to day in patients with sepsis. In this respect, an inverse relation between different HRV components and inflammatory biomarkers has been observed in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, whereas a beneficial effect of ω-3 PUFAs on HRV has been demonstrated in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Consequently, in this article, we suggest that a beneficial effect of ω-3 PUFAs on HRV and clinical outcome in patients with sepsis merits further investigation and could be tested in future clinical trials as a real-time monitoring tool of nutritional manipulation of the inflammatory response in the critically ill.

Keywords: heart rate variability, autonomic nervous system, ω-3 fatty acids, sepsis, lipid emulsions, parenteral, nutrition

Introduction

Acute inflammation is a normal systemic response to different insults, such as severe infection and trauma, and is initiated by the secretion of different cytokines with both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), or IL-10, respectively.1,2 These inflammatory mediators may also induce activation of different brain-derived neuroendocrine immunomodulatory responses, such as the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and both the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which are considered powerful modulators of inflammation.1

In addition, the parasympathetic part of the ANS has been found to exhibit different immunoregulatory properties through the activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway or immunoreflex. Thus, inflammatory mediators seem to activate visceral vagus afferent fibers which terminate within the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) of the medulla oblongata.2 The DVC consists of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMN), and the area postrema (AP). Subsequently, projections from NTS are connected to the DMN, which is the major site of origin of preganglionic vagus efferent fibers. The vagus nerve cholinergic signaling decreases TNF-α production from endotoxin-stimulated human macrophage. This effect is mediated through the interaction between acetylcholine and the α7-subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.2,3

However, in case of dysregulated immune response, a new continuum of disease can occur including sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). In this respect, patients commonly develop nutrient deficiencies, which are associated with an increased risk of developing infections, organ failure, and death.4 Consequently, artificial nutrition route is considered as an integral part of standard care. Recently, the concept of pharmaconutrition has emerged as an alternative approach, considering nutrition an active therapy rather than an adjunctive care.5 Thus, specific nutrients have been designed to modulate the host immune response and suppress systemic inflammation. In this respect, lipid components of artificial nutrition have been found to provide powerful bioactive molecules that may act to reduce inflammatory responses.6

Background: Fish Oil Feeding in the Critically Ill

In Europe, there are currently 3 available lipid emulsions containing omega (ω)-3 fish oil for IV administration: (1) Omegaven (Fresenius Kabi, Germany) that is a 10% fish oil emulsion supplement; (2) Lipoplus/Lipidem (B Braun, Germany) that contains a mixture of 50% medium-chain triglycerides (MCT), 40% soybean oil (SO) that is rich in ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), and 10% fish oil; and (3) Smoflipid (Fresenius Kabi, Germany) that is a 4-oil mixture of 30% SO, 30% MCT, 25% olive oil, and 15% fish oil.

Different clinical trials have shown that fatty acids from fish oil can be considered as powerful disease-modifying nutrients in patients with acute lung injury and sepsis.7,8 Particularly, feeding with the very-long chain, ω-3 PUFAs eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) has been found to inhibit the activity of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) and subsequently to attenuate the production of different cytokines, chemokines, and other effectors of innate immune response.9 In addition, the recent discovery of resolvins generated by EPA and DHA has shed more light on resolution of inflammation, as a possible mechanism of the anti-inflammatory actions of ω-3 PUFAs during systemic inflammation.10 However, oral administration of these compounds is required for several weeks to affect metabolic and inflammatory pathways in humans.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that intravenous administration of fat emulsions rich in ω-3 PUFAs (6-6.5 g/d that is equivalent with 2.3 g EPA plus DHA/day) in patients with sepsis for 5 days from admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) can lead to their rapid incorporation into phospholipids of different cells, such as platelets, or monocytes, within the first 2 days of feeding, reducing serum pro-inflammatory cytokines over the next 7 to 8 days.11–13 In addition, as Mayer and colleagues have suggested in patients with sepsis,11 average doses of fish oil more than 35 g/d (approximately 10 g EPA plus DHA/d) for 5 days can activate endothelial lipoprotein lipases, resulting in rapid hydrolysis of EPA and DHA containing triglycerides with subsequent increase in their plasma levels. Such changes may induce a switch in the predominance of ω-6 over ω-3 to an ω-3 over ω-6 PUFAs predominance, leading to an ω-3 incorporation into the membranes of mononuclear leukocytes. Consequently, potential alterations of membrane fluidity, ion channel opening, and subsequent activation of different signal pathways may lead to decreased production of TNF-α and IL-6.9,11 The bypass of the intestinal process of absorption that is significantly delayed during critical illness could be another reason for such immediate effects (Table 1).

Table 1.

A summary of major studies investigating different effects of fish oil feeding rich in ω-3 PUFAs in critically ill patients with sepsis or septic shock.

| References | Study population | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mayer et al11 | 21 patients with sepsis | PN with ω-6 versus ω-3 PUFAs (350 mL 10%) for 5 days | Increased ω-3/ω-6 ratio within 2 days and rapid incorporation of ω-3 into mononuclear leukocyte membranes |

| Barbosa et al12 | 25 patients with SIRS or sepsis | PN for 5 days with a 50:50 mixture of medium chain FA and soybean oil or a 50:40:10 mixture of medium chain FA, soybean oil, and fish oil | Significant decrease in plasma IL-6 levels. Significant increase in Pao2/Fio2 ratio at day 6 |

| Han et al13 | 38 post-surgical patients | PN for 7 days with a 50:50 mixture of medium chain FA and soybean oil or a 50:40:10 mixture of medium chain FA, soybean oil, and fish oil | Significantly decreased plasma levels of IL-1 and IL-8 on fourth post-operative day |

| Hall et al16 | 41 patients with sepsis | PN with Omegaven 0.5 mL/kg/h daily for 14 days versus standard care | Increased EPA + DHA/AA ratio associated with non-significant increase in survival |

| Manzanares et al14 | 390 ICU patients | Meta-analysis of 6 RCTs | FO containing emulsions were associated with a nonsignificant tendency toward reduced mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation |

| Manzanares et al15 | 733 ICU patients | Meta-analysis of 10 RCTs | Significantly reduced incidence of infection rate and hospital length of stay |

| Pradelli et al17 | 1502 patients (762 ICU patients) | Meta-analysis of 23 studies | Significantly reduced incidence of infection rate and hospital length of stay, both in the ICU and in hospital overall |

| Palmer et al18 | 391 ICU patients | Meta-analysis of 5 RCTs | Significantly reduced length of stay |

| Lu et al19 | 1239 patients with sepsis | Meta-analysis of 17 RCTs | Significantly reduced length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation |

Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; FA, fatty acids; FO, fish oil; ICU, intensive care unit; IL, interleukin; PN, parenteral nutrition; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

In 2014, Manzanares and colleagues after aggregating 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), evaluating the effects of parenteral fish oil on relevant clinical outcomes in a heterogeneous group of critically ill patients, were able to demonstrate a significant reduction in mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation.14 In 2015, the same group of researchers, after analyzing data from 10 RCTs, was not able to find any survival benefit from parenteral fish oil feeding in patients with sepsis.15 Nevertheless, a reduction in the incidence of infections and a trend toward reduced duration of mechanical ventilation and length of stay in the ICU were reported. Furthermore, intravenous fish oil feeding exhibited a non-significant trend toward reduced mortality. In most trials, parenteral doses between 0.1 and 0.2 g/kg/d were used, starting within the first 24 to 48 hours after admission to the ICU. Hall et al16 in a recent RCT suggested that provision of high dose of parenteral fish oil (⩾0.1 g/kg/d) in patients with sepsis resulted in a rapid and significant increase in EPA and DHA, whereas the reduced ratio of arachidonic acid (AA) to both EPA and DHA was associated with improved survival. As conflicting data have been originated from other systematic reviews and meta-analyses,17,18 “low sample size and heterogeneity of the cohorts included do not permit a final recommendation on the use of ω-3 PUFAs as a pharmaconutrient strategy in septic ICU patients.”15 In addition, in the largest meta-analysis conducted so far that included a total of 17 RCTs with 1239 patients with sepsis, Lu et al19 found that both enteral and parenteral fish oil nutritional supplementation may reduce ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation without significantly affecting mortality. However, as they concluded “the very low quality of evidence is insufficient to justify the routine use of omega-3 fatty acids in the management of sepsis”19 (Table 1).

According to the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) Guidelines on Parenteral Nutrition in Intensive Care, the addition of EPA and DHA to lipid emulsions has demonstrable effects on cell membranes and inflammatory processes and fish oil–enriched lipid emulsions likely decrease the length of hospital stay in critically ill patients.20 Canadian recommendations also endorse the use of fish oil–enriched lipid emulsions when parenteral nutrition is indicated.21 Finally, the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) in its recently published guidelines cannot recommend fish oil parenteral feeding in critically ill patients at this time, due to lack of availability on the market of these products in the United States, despite approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2013.22 Nevertheless,

it considers as appropriate its future administration either in patients with septic shock who are candidates for parenteral nutrition due to hemodynamic compromise, such as hypotensive (mean arterial blood pressure < 50 mm Hg), patients for whom catecholamine agents (eg, norepinephrine, epinephrine) are being initiated and patients for whom escalating doses are required to maintain hemodynamic stability, or surgical post-operative patients who are not eligible for enteral nutrition (eg, short bowel).22

A novel anti-inflammatory mechanism of lipid-diet immune-suppressive effects has been described by Luyer et al23 They demonstrated that high-fat enteral nutrition was able to lead to attenuation of systemic inflammation in rats subjected to hemorrhagic shock, through stimulation of cholecystokinin (CCK) receptors and subsequent activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. In this respect, Tracey has suggested that for the development of new therapies and monitoring tools of the activity of the cholinergic pathway in the clinic, new surrogate markers are needed,24 such as heart rate variability analysis (HRV) that is the variability of R-R series in the electrocardiogram (ECG).

Measurement of HRV

In the healthy state, there is some degree of stochastic variability in physiologic variables, such as heart rate (HRV). This variability is a measure of complexity that accompanies healthy systems and has been suggested to be responsible for their greater adaptability and functionality related to pathologic systems.25 Recognition that physiologic time series contain hidden information related to an extraordinary complexity that characterizes physiologic systems has fueled growing interest in applying techniques from statistical physics, for the study of living organisms. Through those techniques different “physiomarkers” can be estimated that fulfill the requirements of contemporary critical care medicine for better and more accurate early warning signs for patients, because they are based on high-frequency measurements and are much more easy to get at the bedside.

In this respect, the development of novel online processing systems supporting real-time processing of multiple high-rate physiological data streams and extraction of different features, such as HRV parameters, has already found correlations between HRV drop and sepsis development even prior to clinical diagnosis.26,27 On the contrary, it has been demonstrated that various “biomarkers” such as cytokines exhibit marked interdependence, pleiotropy (multiple effects), and redundancy (multiple cytokines with the same effect). At the same time, their plasma concentrations fluctuate from day to day and correlate poorly with classic physiologic variables in patients with sepsis.27,28

The RR variations may be evaluated by several methods.

Time domain methods

Time domain methods determine heart rate or RR intervals in continuous ECG records. Each QRS complex is detected and the normal-to-normal (NN) intervals (all intervals between adjacent QRS complexes) are calculated. Other time domain variables include the mean NN interval, the mean heart rate, or the difference between the longest and the shortest NN interval, as well. The simplest of these metrics is the standard deviation of the NN intervals (SDNN), which is the square root of the variance. However, it should be emphasized that SDNN becomes less accurate with shorter monitoring periods. The most commonly used time domain methods are the square root of the mean squared differences of successive NN intervals (RMSSD), the number of interval differences of successive NN intervals greater than 50 ms (NN50), and the proportion derived from dividing NN50 by the total NN intervals (pNN50).29

Frequency domain methods

Heart rate variability can also be estimated via frequency domain methods that calculate the different frequency components of a heart rate signal through a fast Fourier transformation (FFT) of an R-R time series. The method displays in a plot the relative contribution of each frequency,29 whereas the area under a particular band is a measure of its variability (power). This plot includes at least 3 peaks. Fast periodicities in the range of 0.15 to 0.4 Hz (high frequency [HF]) are largely due to the influence of vagal tone. Recently, it has been found that central muscarinic cholinergic stimulation (usually in the context of balancing cytokine production) is also accompanied by activation of the HF component of HRV and an instantaneous increase in total variability.30 Low-frequency periodicities (LF), in the region of 0.04 to 0.15 Hz, are produced by baroreflex feedback loops, affected by both sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation of the heart and very low frequency periodicities (VLF, less than 0.04 Hz) have been variously ascribed to modulation by the influence of vasomotor activity. The LF/HF ratio has been suggested to reflect sympathovagal balance.29,31

ECG signals must satisfy several technical requirements to obtain reliable information. The optimal sampling frequency range should be between 250 and 500 Hz. Ectopic beats, arrhythmic events, missing data, and noise effects should be properly filtered and omitted. Frequency domain methods must be preferred in cases of short-term investigations. The recordings should last for at least 10 times the wavelength of the lower frequency bound, thus recordings of approximately 1 minute can assess the HF component of HRV while 2 minutes are needed for the LF component. In conclusion, 5-minute recordings are preferred, unless the aim of the study dictates a different design.29

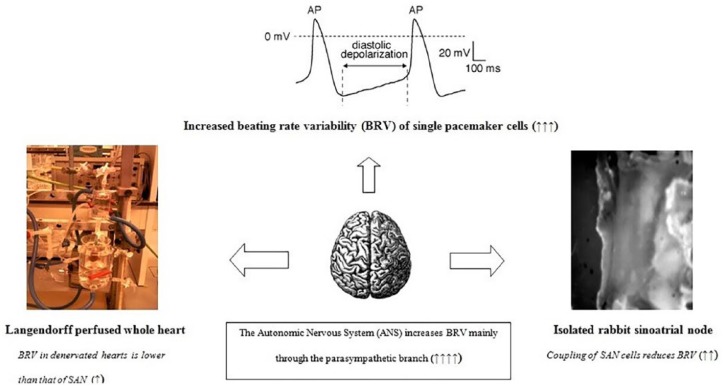

Figure 1 depicts the different mechanisms contributing to HRV, at the cellular (beating rate variability—BRV), tissue, and whole organ level, as well as the impact of ANS on heart rate dynamics.

Figure 1.

Heart rate variability (HRV) at different levels of organization. HRV or beating rate variability (BRV) of single pacemaker cells is much more increased compared to the whole sinus atrial node (SAN), because electrical coupling of different cells attenuates pacemaker discharge variability in toto. Furthermore, HRV in ex vivo denervated whole heart preparations seems to be lower than that of sinus node, whereas autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity increases significantly HRV, mainly through the para-sympathetic branch. Upon inflammation, different experimental studies suggest low HRV either due to reduced responsiveness of pacemaker cells to ANS input and reduced cell-to-cell coupling or attenuation of ANS effects upon the heart, related to hypercytokinemia.

Linking HRV, Fish Oil Feeding, and Systemic Inflammation

HRV and inflammatory response

Alterations in HRV during septic shock and MODS have been reported from different research groups.27,32–34 In this respect, Goldstein found that both increased total variability and LF power were associated with recovery and survival, whereas a decrease in total power, LF/HF, and LF power correlated with severity of illness and mortality in patients with sepsis, 48 hours after being admitted to the ICU.32 This loss of variability of heart rate signals has been attributed to a “decomplexification,” which is associated with a defective communication between different organs due to ANS dysfunction and parallels severity of disease.

In an animal study of experimental endotoxemia, induced by administration of lipopolysacchraride (LPS, endotoxin derived from the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria), Fairchild and colleagues demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between SDNN and total power of RR time series and peak concentrations of different cytokines, 3 to 9 hours post-LPS.35 The same results were found after administration of recombinant TNF-α. It was suggested that mechanisms responsible for decrease in HRV could be related to effects of LPS and/or cytokines on various ion channels.33 Tateishi et al36 investigated the relationships between HRV and IL-6 upon admission in a cohort of 45 patients with sepsis and they found that IL-6 exhibited significant negative correlations with both LF and HF power values. These findings indicate a possible association between low HRV indices and hypercytokinemia in patients with sepsis.37 Moreover, clinical data from different studies involving patients with coronary artery disease,38 heart failure,39 and healthy subjects with increased risk factors for heart diseases40 suggest that there is an inverse association between different inflammatory biomarkers, such as white blood cell count, IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP), and ANS activity, estimated through HRV analysis.37

A potential link between HRV alterations during sepsis and different plasma lipid profiles has been suggested by Nogueira and colleagues.41 In this respect, an inverse relation between HRV, cardiac histological damage, and increased plasma levels of ω-6 free fatty acids has been found in nonsurvivor patients with sepsis. As a predominance of ω-3 over ω-6 to ω-6 over ω-3 PUFAs upon fish oil feeding has been suggested in different studies,11–13 someone could postulate that HRV alterations might also be influenced by changes in plasma free fatty acid levels. Such changes have also been found to correlate significantly with alterations in LF/HF ratio in noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients.42

In conclusion, the reduction in instantaneous HRV has been associated with an overproduction of cytokines, whereas pharmacological stimulation of the efferent vagus nerve has been found to increase the HF component of HRV and inhibit at the same time TNF-α secretion in septic animals.43

Nevertheless, as no relationship was found between HRV and inflammatory markers in one study with endotoxin administration in healthy volunteers,44 it was suggested that vagus nerve innervation of the heart does not reflect outflow to other organs, such as the spleen, one of the major cytokine-producing organs.2,24 In addition, other experimental studies indicate that the threshold of vagal activity that stimulates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway is significantly lower than that required to activate a change in instantaneous HRV.45 As basal vagal input to the spleen may be different from vagal input to the heart, it has been postulated that HRV might not be an appropriate method to assess activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.44 These findings strengthen the notion that autonomic outflow cannot be regarded as a general response, but appears to be organ-specific.24

Moreover, results from human and animal experimental studies indicate that apart from autonomic dysfunction, intracardiac mechanisms might also be responsible for reduced HRV during sepsis.46–48 These studies have demonstrated that different membrane channel proteins and especially the so-called funny current, an inward hyperpolarization current that drives diastolic depolarization and spontaneous pacemaker activity, are altered upon LPS administration. Furthermore, membrane channel kinetics seems to have significant impact on HRV, whose early decrease might reflect a cellular metabolic stress. In this respect, during severe sepsis, an unfavorable metabolic milieu could affect ionic current gating or membrane receptor densities, with significant impact on level and variability of pacemaking discharge.49 In addition, a possible reduced responsiveness of sinus atrial node cells to external stimuli could also negatively affect HRV.48,49

In conclusion, because there are no human data confirming association between HRV and activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway at the bedside, it has been proposed that such potential relationships should be investigated in the context of clinical trials of dietary fat supplementation in patients with inflammatory diseases.24 Moreover, implementation of novel signal processing techniques developed by complexity scientists, such wavelet transformation (WT) of heart rate signals, has been proposed as more accurate estimate of ANS output.50,51

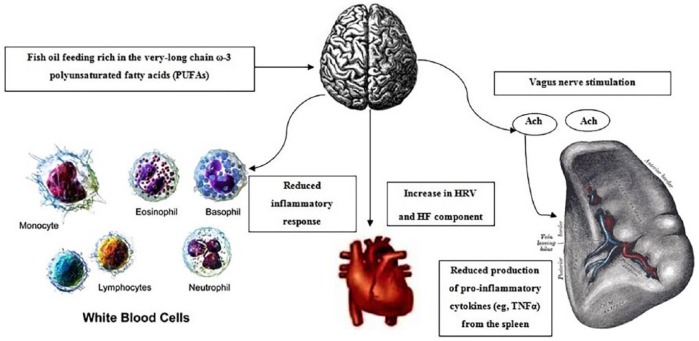

Figure 2 illustrates the basic concepts of our hypothesis regarding fish oil effects on HRV and subsequent attenuation of the inflammatory response during acute critical illness.

Figure 2.

The basic concepts of our hypothesis. Briefly, fish oil feeding through down regulation of cytokine production and subsequent vagus nerve activation and release of acetylcholine at the level of the spleen might further attenuate the release of different cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which is mainly produced from activated macrophages in the spleen. Moreover, an increase in the high-frequency (HF) component of heart rate variability (HRV) could be continuously monitored through HRV analysis of heart rate signals using HF measurements, by adopting novel online processing systems. Consequently, a reduced inflammatory response could be easily detected at the bedside, through autonomic nervous system (ANS) output monitoring.

HRV and fish oil feeding in patients with cardiovascular diseases

Several years ago, the US Physicians’ Health Study that included a total of 20 551 physicians 40 to 84 years old and without a history of cardiovascular diseases showed that consumption of fish at least once per week might reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death.52

The investigators of the GISSI-Prevenzione Trial studied 11 324 patients with known cardiovascular diseases who were randomized to receive 300 mg of vitamin E, 850 mg of ω-3 PUFA, both, or neither. After 3.5 years, the group receiving ω-3 PUFA alone had a 45% reduction in sudden death and a 20% reduction in all-cause mortality.53

Christensen et al54 to evaluate the association between HRV and fish oil feeding randomized for the first time patients with ischemic heart diseases to 5.2 g of ω-3 PUFA daily (8 capsules) for 12 weeks or a comparable amount of olive oil. The HRV parameter SDNN increased significantly from 115 to 124 ms in the ω-3 PUFA group. Moreover, in a subsequent study, the same investigators55 demonstrated that daily supplement of 6.6 g ω-3 PUFAs, 2 g ω-3 PUFAs, or placebo (olive oil) for 12 weeks in healthy individuals can induce an incorporation of DHA into the membranes of granulocytes. Such effects were also found to be associated with a dose-response increase in HRV, something that might protect against serious ventricular arrhythmias (Table 2).

Table 2.

A summary of major studies investigating the influence of fish oil feeding rich in ω-3 PUFAs on heart rate variability in different groups of patients.

| References | Study population | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen et al54 | 49 patients with CAD | 4.3 g EPA/DHA daily versus placebo for 12 weeks | Significant increase in SDNN |

| Christensen et al55 | 40 healthy individuals | 1.68 g EPA/5.9 g DHA daily versus placebo for 12 weeks | Dose-dependent increase in HRV. Positive correlation between SDNN and DHA levels in the cell |

| Pluess et al56 | 8 healthy individuals | 0.5 g/kg 10% Omegaven 48 and 72 hours before LPS administration (2 ng/kg) versus placebo | Significantly reduced TNF-α, norepinephrine, and ACTH levels |

| Nodari et al58 | 44 patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy | 1.44 g EPA/DHA daily versus placebo for 24 weeks | Significantly increased LF/HF ratio during mental stress |

| Mozaffarian et al59 | 4.263 ECGs | Fish consumption using food frequency questionnaire | Significantly increased RMSSD and HF, lower LF |

| Xin et al64 | 692 patients due to multiple causes | Meta-analysis of 15 RCTs with median dose of FO ranging between 640 and 5900 mg/d and median duration of 12 weeks | Significantly increased HF |

| Christensen et al66 | 43 patients with DM type 1 and 38 with DM type 2 | Fish consumption using food frequency questionnaire | Increased ω-3 PUFA content in platelets with a positive correlation with HRV in patients with DM type 1 |

| Ninio et al67 | 46 overweight patients | 0.8 g EPA/DHA daily versus placebo for 12 weeks | Significantly increased HF and decreased resting HR |

| Christensen et al72 | 17 patients with renal failure | 4.7 g EPA/DHA daily versus placebo for 12 weeks | Significantly increased SDNN associated with the amount of ω-3 PUFA in granulocytes |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adreno-corticotropin hormone; CAD, coronary artery disease; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; HF, high-frequency; HRV, Heart rate variability; LF, Low-frequency; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RMSSD, root of the mean squared differences of successive NN intervals; SDNN, standard deviation of the NN intervals; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

It has been suggested that such effects of fish oil reflect an enhanced efferent vagal activity via a central-acting mechanism, due to a possible suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines that have been found to inhibit central vagal neurons.9 In this respect, parasympathetic predominance due to fish oil supplementation during acute inflammation has been proposed by Pluess et al56; they found that the intravenous administration of fish oil with ω-3 PUFAs (twice 0.5 g/kg 10% emulsion/Omegaven), 48 and 24 hours before endotoxin injection (2 ng/kg) in healthy volunteers, was able to blunt fever response and sympathetic stimulation, estimated with HRV analysis and LF/HF ratio. This reduction was associated with a significant decrease in plasma norepinephrine and adreno-corticotropin hormone (ACTH) levels.

Abuissa and colleagues have suggested that oral supplementation of ω-3 PUFAs increases instantaneous HRV, reduces LF/HF ratio, and confers protection against ischemia-induced ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death with nutritional doses (⩽1 g/d), whereas pharmacological doses of 3 to 5 g/d might protect against sudden cardiac death by inhibiting the production of thromboxane A2 and inflammatory cytokines.57

Thus, Nodari et al58 investigated the effects of ω-3 PUFA on HRV in 44 patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy who were randomized to either 1 g capsules of ω-3 PUFA or olive oil capsules, for 6 months. Compliance was monitored by measuring the plasma levels of ω-3 PUFA before and after intervention. The LF/HF ratio showed a 55% decrease in the treatment group versus a 54% increase in the placebo group, indicating a favorable shift in the cardiac autonomic balance (Table 2).

In a large study including more than 5000 subjects aged more than 65 years old, Mozaffarian found that individuals with the highest fish consumption (⩾5 meals/week) exhibited 1.5 ms greater HRV compared to those with the lowest fish consumption.59 In addition, high ω-3 PUFA intake was associated with enhanced vagal activity and increased plasma phospholipid levels of both EPA and DHA, indicating a favorable impact on autonomic function (Table 2).

Based on the results from previous studies, Lee and colleagues have suggested that patients with known coronary heart disease should consume at least 1 g daily of ω-3 PUFAs from fish or fish oil supplements whereas subjects without heart diseases should consume 200 to 250 mg daily, respectively.60

However, a recently published Cochrane meta-analysis of 79 trials that involved more than 112 000 patients found that increasing EPA and DHA had little or no effect on all-cause deaths and cardiovascular events.61 Furthermore, taking ω-3 PUFAs capsules did not reduce incidence of heart disease, stroke, or death significantly.

Furthermore, different interventional studies on ω-3 PUFAs and HRV in patients with heart disease have found inconsistent results, with only 8 out of the 20 trials published so far, supporting a beneficial effect on HRV.37,62 Reasons for such inconsistency might include heterogeneous populations, limited sample sizes, or different study protocols with variable administered doses of ω-3 PUFA (1.5-6.6 g/d) and length of intervention (4-23 weeks).62 Another potential limitation of such measures could be associated with the fact that a reduction in pacemaker funny current rather than an alteration in autonomic neural output was found to be responsible for heart rate reduction and increase in HRV in an animal study with administration of ω-3 PUFAs.62,63

Nevertheless, in a recent meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials investigating the short-term (median 12 weeks) effects of oral fish oil supplementation (1-4 g/d) on HRV in humans,64 Xin and colleagues were able to show that ω-3 PUFA intake had a favorable impact on frequency components of HRV, as indicated by an increase in HF and decrease in LF/HF ratio. Such findings suggest that parasympathetic predominance could be responsible for the antiarrhythmic and other beneficial effects of fish oil feeding.62,64

HRV and fish oil feeding in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure

Administration of ω-3 PUFA has been found to inhibit HMG-CoA reductase and reduce plasma triglyceride concentration similarly with statins. In addition, they seem to modulate renin formation, enhance endothelial nitric oxide generation, increase insulin sensitivity, and inhibit angiotensin-converting enzyme activity.62,65 As a result, it has been suggested that fish oil feeding could be considered as a “polypill,” incorporating diuretic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-hypertensive properties.65 Such beneficial effects might be partially attributed to ANS balance restoration, which could be monitored through HRV analysis.

In this respect, Christensen et al66 evaluated HRV in 43 patients with type 1 and 38 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and related different frequency components with ω-3 PUFA content in platelet membranes. It was shown that in type 1 patients, HRV increased with increasing levels of DHA whereas a positive correlation between HRV and platelet DHA was found in patients receiving insulin therapy. In addition, overweight subjects with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus seem to exhibit reduced HRV.62 Ninio et al,67 in a study including 65 overweight subjects, showed that supplementation of DHA 1.56 g/d and EPA 0.36 g/d for 12 weeks improved HRV by increasing HF power and reduced heart rate at rest and during submaximal exercise (Table 2).

Different studies have shown that ω-3 PUFA supplementation less than 4 g/d might reduce proteinuria in patients with chronic kidney diseases68,69 and slow immunoglobulin A nephropathy.70 In addition, in a recent study,71 a 6 month intake of fish oil was found to decrease urinary excretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), which increases production of IL-6 in patients suffering from chronic kidney disease, indicating inhibition of its production by tubular epithelial cells. However, no study so far has evaluated a potential link between such anti-inflammatory effects of ω-3 PUFA and HRV indices in patients with kidney diseases. Never-the-less, in patients with chronic kidney disease with or without dialysis treatment Christensen et al72 have shown that supplementation of more than 5 g/d of ω-3 PUFA for 12 weeks led to a significant correlation between ω-3 PUFA in granulocytes and the HRV parameter SDNN. However, HRV was not increased upon fish oil feeding, probably because of very low HRV indices and low levels of ω-3 PUFA at baseline (Table 2).

In conclusion, it seems that patients with sympathetic overactivity or dysfunction of the ANS, such as patients with sepsis, cardiovascular diseases, renal failure, and diabetes mellitus, have reduced HRV that might be favorably influenced by fish oil feeding supplementation. However, more than 10 to 12 weeks of oral intake is needed for such beneficial effects whereas no study has confirmed so far if dietary or pharmacological doses are necessary for restoring autonomic balance through parasympathetic predominance. Finally, a potential association between HRV indices and immunoregulatory effects of ω-3 PUFA remains to be evaluated in future clinical studies in patients with sepsis.

Suggestions for Future Clinical Testing and Potential Implications

An association has been suggested between increased HRV and fish oil administration in different groups of patients with cardiovascular diseases.54,57,62,64 However, the possible relationship between HRV changes and inflammatory markers during fish oil feeding has not been studied yet, in patients with sepsis. Thus, we think that a promising approach could be the assessment of the relationship between vagal activity estimated with HRV and inflammatory markers in such patients, during parenteral fish oil feeding. In this case, we assume a beneficial effect of ω-3 PUFAs on HRV and cytokine response, early in the course of disease.11–13,56 Consequently and as the current evidence is still too weak and sparse to make recommendations about the role of fish oil in the treatment of the critically ill,14–19,59 HRV could be adopted as end point for monitoring nutritional manipulation of inflammatory response at the bedside, helping translation of basic science results into successful randomized controlled trials. In this case, we assume that ω-3 PUFAs upon parenteral administration will be rapidly incorporated into the phospholipid membranes of different immune cell types, reducing the inflammatory response and increasing HRV.

In this respect and similar to the study by Han,13 24 h recordings and longitudinal changes of HRV could be measured in 2 groups of patients with sepsis with similar severity of disease. Patients with Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score (APACHE II) > 25, immunosuppressive therapy, myocardial infarction (within last 3 months), arrhythmia, stroke, severe hematological diseases, creatinine > 2.5 mg/dL, plasma triglyceride levels > 500 mg/dL, bilirubin > 2.5 mg/dL, and known allergy to eggs should be excluded from such study.11,13 Parenteral nutrition should be administered for at least 7 days, with the same volume of glucose, nitrogen, and fat but different lipid composition.13 In addition, different doses of ω-3 PUFAs could be tested, starting from doses higher than 0.1 g/kg/d, which have been found to be clinically favorable.13 According to the ASPEN guidelines for artificial nutrition in the critically ill,22 we suggest that such an investigation should be undertaken either in patients with septic shock who are candidates for parenteral nutrition due to hemodynamic compromise or surgical post-operative patients who are not eligible for enteral nutrition. As an inverse relation between HRV, plasma free fatty acid levels, and inflammatory response has been found in the most severely ill patients with septic shock and the highest level of inflammatory indices,28,41 we think that such a cohort would be the most appropriate candidate for assessing fish oil immunomodulatory effects and its impact on HRV during the acute phase of critical illness. In case that HRV metrics predict outcomes of interest, such as lower infection rate and/or attenuated organ dysfunction, such a study might identify a unique value of HRV analysis as a monitoring tool of inflammatory modulation by omega-3 PUFAs in patients with sepsis. Finally, a positive correlation between HRV metrics and plasma lipid changes during fish oil feeding might reveal a new link between ANS activity and lipid metabolism in patients with sepsis.

Another potential use of HRV in artificial nutrition of patients with sepsis as has been suggested by Tracey73 could be its adoption as a physiomarker to early identify patients with reduced vagal tone. In this case, a susceptibility to increased inflammation can be assumed whereas HRV metrics might serve as an early alarm to identify patients who might benefit from pharmacological stimulation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, by administration of ω-3 PUFAs.

In case that the immunoreflex does not involve cardiac inhibitory fibers, as has been suggested from one experimental study investigating electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve in septic animals,45 HRV might lack accuracy for evaluating immunomodulatory effects of fish oil feeding. Nevertheless, clinical data are still lacking, whereas in such case, HRV monitors could continuously provide salient information on whether different doses of ω-3 PUFAs can selectively activate the lower threshold signaling fibers of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway without stimulating cardiac fibers, which require higher stimulation intensity to fire.24,73

Conclusions

Different clinical and experimental studies have established an interrelation between ANS output and inflammatory regulation, whereas the discovery of the “cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway” has expanded our understanding of how the nervous system modulates the inflammatory response through an immunoreflex.

Fish oil feeding has been found to have anti-inflammatory effects in different groups of patients, whereas a potential impact of ω-3 PUFAs on HRV has been suggested in patients with cardiovascular and renal diseases. In this respect, it has been recently proposed that HRV could be considered a biomarker to study the potential health benefits of different eat items and evaluate the influence of nutrition on both mental and physical health.74 However, no study so far has investigated the relation between ANS output and immune response in patients with sepsis during fish oil nutrition. As early and more accurate monitoring of critically ill patients through continuous automated detection of abnormal variability of heart rate signals can alert clinicians to impending clinical deterioration and allow earlier intervention, such an analysis could also be tested as a novel surrogate marker of ω-3 PUFAs’ immunomodulatory effects. In case of positive results, HRV could be adopted as a monitoring tool at the bedside, linking pharmaconutrition to different outcomes of interest.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: V.P. is the primary author and performed majority of literature research. I.P. assisted in preparation of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Vasilios Papaioannou  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2637-0160

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2637-0160

References

- 1. Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:125–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tracey KJ. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goode HF, Cowley HC, Walker BE, Howdle PD, Webster NR. Decreased antioxidant status and increased lipid peroxidation in patients with septic shock and secondary organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones NE, Heyland DK. Pharmaconutrition: a new emerging paradigm. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wanten GJ, Calder PC. Immune modulation by parenteral lipid emulsions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1171–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singer P, Theilla M, Fisher H, Gibstein L, Grozovski E, Cohen J. Benefit of an enteral diet enriched with eicosapentaenoic acid and gamma-linolenic acid in ventilated patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pontes-Arruda A, Aragao AM, Albuquerque JD. Effects of enteral feeding with eicos-pentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2325–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singer P, Shapiro H, Theilla M, Anbar R, Singer J, Cohen J. Anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3 fatty acids in critical illness: novel mechanisms and an integrative perspective. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1580–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mayer K, Gokorsch S, Fegbeutel C, et al. Parenteral nutrition with fish oil modulates cytokine response in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1321–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barbosa VM, Miles EA, Calhau C, Lafuente E, Calder PC. Effects of a fish oil containing lipid emulsion on plasma phospholipid fatty acids, inflammatory markers, and clinical outcomes in septic patients: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Han YY, Lai SL, Ko WJ, Chou CH, Lai HS. Effects of fish oil on inflammatory modulation in surgical intensive care unit patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manzanares W, Dhaliwal R, Jurewitsch B, Stapleton RD, Jeejeebhoy KN, Heyland DK. Parenteral fish oil lipid emulsions in the critically ill: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manzanares W, Langlois PL, Dhaliwal R, Lemieux M, Heyland DK. Intravenous fish oil lipid emulsions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015;19:R167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hall TC, Bilku DK, Neal CP, et al. The impact of an omega-3 fatty acid rich lipid emulsion on fatty acid profiles in critically ill septic patients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2016;112:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pradelli L, Mayer K, Muscaritoli M, Heller AR. n-3 fatty acid enriched parenteral nutrition regimens in elective surgical and ICU patients: a meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Palmer AJ, Ho CKM, Ajibola O, Avenell A. The role of n-3 fatty acid supplemented parenteral nutrition in critical illness in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu C, Sharma S, McIntyre L, et al. Omega-3 supplementation in patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singer P, Berger MM, Van den Berghe G, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on parenteral nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dhaliwal R, Cahill N, Lemieux M, Heyland DK. The Canadian critical care nutrition guidelines in 2013: an update on current recommendations and implementation strategies. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40:159–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luyer MD, Greve JWM, Hadfoune M, Jacobs JA, Dejong CH, Buurman WA. Nutritional stimulation of cholecystokinin receptors inhibits inflammation via the vagus nerve. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1023–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tracey KJ. Fat meets the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1017–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buchman TG. The community of the self. Nature. 2002;420:246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kennedy H. Heart rate variability—a potential, noninvasive prognostic index in the critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:213–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seely AJE, Christou NV. Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: exploring the paradigm of complex nonlinear systems. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2193–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Friedland JS, Porter JC, Daryanani S, et al. Plasma proinflammatory cytokine concentrations, APACHE III scores and survival in patients in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1775–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Munford RS, Tracey KJ. Is severe sepsis a neuroendocrine disease. Mol Med. 2002;8:437–442. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malik M, Camm AJ. Components of heart rate variability: what they really mean and what we really measure. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:821–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goldstein B, Buchman TG. Heart rate variability in intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 1998;13:252–265. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldstein B, Fiser DH, Kelly MM, Mickelsen D, Ruttimann U, Pollack MM. Decomplexification in critical illness and injury: relationship between heart rate variability, severity of illness, and outcome. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmidt H, Muller-Werdan U, Hoffmann T, et al. Autonomic dysfunction predicts mortality in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome of different age groups. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1994–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fairchild KD, Saucerman JJ, Raynor LL, et al. Endotoxin depresses heart rate variability in mice: cytokine and steroid effects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1019–R1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tateishi Y, Oda S, Nakamura M, et al. Depressed heart rate variability is associated with high IL-6 blood level and decline in blood pressure in septic patients. Shock. 2007;28:549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Papaioannou V, Pneumatikos I, Maglaveras N. Association of heart rate variability and inflammatory response in patients with cardiovascular diseases: current strengths and limitations. Front Physiol. 2013;4:174. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. von Känel R, Carney RM, Zhao S, Whooley MA. Heart rate variability and biomarkers of systemic inflammation in patients with stable coronary heart diseases: finding from the Heart and Soul Study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aronson D, Mittleman MA, Burger AJ. Interleukin-6 levels are inversely correlated with heart rate variability in patients with decompensated heart failure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lampert R, Bremner JD, Su S, et al. Decreased heart rate variability is associated with higher levels of inflammation in middle-aged men. Am Heart J. 2008;156:759.e1–759.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nogueira AC, Kawabata V, Biselli P, et al. Changes in plasma free fatty acid levels in septic patients are associated with cardiac damage and reduction in heart rate variability. Shock. 2008;29:342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Manzella D, Barbieri M, Rizzo MR, et al. Role of free fatty acids on cardiac autonomic nervous system in noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients: effects of metabolic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2769–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, et al. Central muscarinic cholinergic regulation of the systemic inflammatory response during endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5219–5223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kox M, Ramakers BP, Pompe JC, van der Hoeven JG, Hoedemaekers CW, Pickkers P. Interplay between the acute inflammatory response and heart rate variability in healthy human volunteers. Shock. 2011;36:115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huston JM, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani M, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation reduces serum high mobility group box I levels and improves survival in murine sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2762–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zorn-Pauly K, Pelzmann B, Lang P, et al. Endotoxin impairs the human pacemaker current IF. Shock. 2007;28:655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Klockner U, Rueckschloss U, Grossmann C, et al. Differential reduction of HCN channel activity by various types of lipopolysaccharide. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Papaioannou V, Verkerk AO, Amin AS, de Bakker JM. Intracardiac origin of heart rate variability, pacemaker funny current and their possible association with critical illness. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013;9:82–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Griffin MP, Lake DE, Bissonette EA, Harrell FE, Jr, O’Shea TM, Moorman JR. Heart rate characteristics: novel physiomarkers to predict neonatal infection and death. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1070–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goldberger AL. Non-linear dynamics for clinicians: chaos theory, fractals, and complexity at the bedside. Lancet. 1996;347:1312–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Frick P, Grossman A, Tchamician P. Wavelet analysis of signals with gaps. J Math Phys. 1998;39:4091–4107. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Albert CM, Hennekens CH, O’Donnell CJ, et al. Fish consumption and risk of cardiac death. JAMA. 1998;279:23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto miocardico. Lancet. 1999;354:447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Christensen JH, Gustenhoff P, Korup E, et al. Effect of fish oil on heart rate variability in survivors of myocardial infarction: a double blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:677–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Christensen JH, Christensen MS, Dyerberg J, Schmidt EB. Heart rate variability and fatty acid content of blood cell membranes: a dose-response study with n-3 fatty acids. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pluess T-T, Hayoz D, Berger MM, et al. Intravenous fish oil blunts the physiological response to endotoxin in healthy subjects. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:789–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Abuissa HO, O’Keefe JH, Jr, Harris W, Lavie CJ. Autonomic function, Omega-3, and cardiovascular risk. Chest. 2005;127:1088–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nodari S, Metra M, Milesi G, et al. The role of n-3 PUFAs in preventing the arrhythmic risk in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2009;23:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mozaffarian D, Stein PK, Prineas RJ, Siscovick DS. Dietary fish ω-3 fatty acid consumption and heart rate variability in US adults. Circulation. 2008;117:1130–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee JH, O’Keefe JH, Lavie CJ, Harris WS. Omega-3 fatty acids: cardiovascular benefits, sources and sustainability. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Abdelhamid AS, Brown TJ, Brainard JS, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardio-vascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD003177. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003177.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Christensen JH. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and heart rate variability. Front Physiol. 2011;2:84. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Verkerk AO, den Ruijter HM, Bourier J, et al. Dietary fish oil reduces pacemaker current and heart rate in rabbit. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1485–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Xin W, Wei W, Li X-Y. Short-term effects of fish-oil supplementation on heart rate variability in humans: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:926–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Das UN. Essential fatty acids and their metabolites could function as endogenous HMG-CoA reductase and ACE enzyme inhibitors, anti-arrhythmic, anti-hyper-tensive, anti-atherosclerotic, anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective, and cardio-protective molecules. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Christensen JH, Skou HA, Madsen T, Torring I, Schmidt EB. Heart rate variability and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Intern Med. 2001;249:545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ninio DM, Hill AM, Howe PR, Buckley JD, Saint DA. Docosahexaenoic acid-rich fish oil improves heart rate variability and heart rate responses to exercise in overweight adults. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:1097–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. De Caterina R, Endres S, Kristensen SD, Schmidt EB. n-3 fatty acids and renal diseases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;24:397–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gopinath B, Harris DC, Flood VM, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P. Consumption of long-chain n-3 PUFA, alpha-linolenic acid and fish is associated with the prevalence of chronic kidney disease. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:1361–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Donadio JV, Bergstralh EJ, Jr, Offord KP, Spencer DC, Holley KE. A controlled trial of fish oil in IgA nephropathy. Mayo nephrology collaborative group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1194–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pluta A, Strozecki P, Kesy J, et al. Beneficial effects of 6-month supplementation with omega-3 acids on selected inflammatory markers in patients with chronic kidney diseases stages 1–3. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1680985. doi: 10.1155/2017/1680985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Christensen JH, Aaroe J, Knudsen N, et al. Heart rate variability and n-3 fatty acids in patients with chronic renal failure—a pilot study. Clin Nephrol. 1998;49:102–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Huston JM, Tracey KJ. The pulse of inflammation: heart rate variability, the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and implications for therapy. J Intern Med. 2011;269:45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Young HA, Benton D. Heart rate variability: a biomarker to study the influence of nutrition on physiological and psychological health. Behav Pharmacol. 2018;29:140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]