Abstract

Redistribution of the water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4) away from astrocyte endfeet and into parenchymal processes is a striking histological feature in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurological conditions with prominent astrogliosis. AQP4 redistribution has been proposed to impair bulk Aβ clearance in AD, resulting in increased amyloid deposition in the brain; however, this finding is controversial. Here, we provide evidence in support of a different and novel role of AQP4 in AD. We found that Aqp4 deletion significantly increased amyloid deposition in cerebral cortex of 5xFAD mice, with an increase in the relative number of fibrillar vs. dense core plaques. AQP4 deficient 5xFAD mice also showed a significant reduction in the density of GFAP labeled peri-plaque astrocyte processes. Microglial plaque coverage was also significantly reduced, suggesting astrocyte involvement in organizing the peri-plaque glial response. The alterations in peri-plaque glial structure were accompanied by increased neuronal uptake of Aβ and an increase in the number of dystrophic neurites surrounding plaques. On the basis of these findings, we propose that redistribution of AQP4 into the parenchymal processes facilitates astrocyte structural plasticity and the formation of a reactive glial net around plaques that protects neurons from the deleterious effects of Aβ aggregates. AQP4 redistribution may thus facilitate plaque containment and reduce neuropathology in AD.

Keywords: Astroglia, Water channel, Neurodegeneration, Glial barrier

Introduction

In healthy brain the water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4) is heavily enriched at the endfeet of astrocytes in the form of supramolecular aggregates that appear as orthogonal arrays in freeze-fracture electron micrographs of the endfoot membrane [38, 48]. AQP4 is upregulated and redistributed in reactive astrocytes, and becomes prominently expressed in parenchymal astrocyte processes in rodent models of many neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) [50, 56]. The significance of AQP4 redistribution in AD is uncertain. One explanation has been offered, a ‘glymphatic’ hypothesis proposing that mislocalization of AQP4 causes failure of a trans-endfoot convective fluid flow, which impairs clearance of toxic protein aggregates from the brain parenchyma into the peri-venular spaces during sleep [23, 54]. In support of this hypothesis, an increase in β-amyloid deposition has been observed in APP/PS1 mice that lack AQP4 [55], and human AQP4 polymorphisms have been reported as a genetic risk factor for AD [7, 37]. However, the plausibility of the ‘glymphatic’ hypothesis has been questioned on theoretical grounds [2, 21, 24] and from the fact that clearance of β-amyloid aggregates occurs primarily via the peri-arterial and not the peri-venular spaces [1, 8]. Further, the relevance of the glymphatic hypothesis to human disease is unclear due to differences in AQP4 distribution between rodents and humans [16], and in independent studies we did not observe AQP4-facilitated parenchymal convection [44]. Therefore, alternative mechanisms may be needed to explain the deleterious effect of Aqp4 deletion in experimental AD models.

Astrogliosis is a pathological hallmark of AD with complex effects on disease progression [4, 12, 49]. Reactive astrocytes phagocytose amyloid aggregates and dystrophic synapses [19, 34, 52], form a reactive glial net that surrounds and invades plaques [6], and are involved in the inflammatory response to amyloid deposition [53]. AQP4 facilitates astrocyte migration and glial scar formation in the response to traumatic brain injury [3, 39] and is involved in astrocyte cytokine release in response to neuroinflammation [30]. AQP4 function as an effector in the astrocyte response to brain injury suggests that its redistribution to peri-plaque astrocyte processes might be an important component of the astrocyte response in AD, rather than a pathological consequence of endfoot damage.

Here, we compared amyloid deposition and peri-plaque astrocyte structure in the 5xFAD mouse model of AD [35] bred with Aqp4 knockout mice. We found increased amyloid deposition in Aqp4 knockout 5xFAD mice compared with wild-type 5xFAD littermates, with marked alterations in plaque structure, peri-plaque astrocyte and microglial organization, and neuronal injury surrounding plaques. These results demonstrate that parenchymal AQP4 participates in peri-plaque astrocyte structural reorganization, and support a novel role for AQP4 in AD pathogenesis in which its redistribution facilitates plaque containment and reduces neuropathology.

Materials and Methods

Mice

5xFAD mice overexpressing human APP and PSEN1 with AD-associated mutations were obtained from the NIH mutant mouse research and resource center (MMRCC). These mice were bred with Aqp4−/− mice on a C57Bl/6 background that were previously generated in our laboratory [32]. Offspring were genotyped for APP and PSEN1 (which co-segregated as expected) and for Aqp4. F1 offspring that were heterozygous at all 3 loci (5xFAD+/−; Aqp4+/−) were then interbred and F2 offspring were genotyped as before. F2 offspring that were heterozygous for APP and PSEN1 and either wild-type or homozygous negative for Aqp4 (5xFAD+/−; Aqp4+/+ or 5xFAD+/−; Aqp4−/−) were maintained until 7–9 months of age and then sacrificed by transcardial perfusion with 4% formaldehyde and the brain was processed for paraffin embedding. All procedures were approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 5 Aqp4−/− 5xFAD mice and 8 wild-type littermates were used in this study.

Human samples

Tissue was obtained from the UCSF neurodegenerative disease brain bank, 3 AD and 3 control samples were studied. AD samples (2 M, 1F) had both clinical and neuropathological diagnosis of AD without comorbidity, mean age at death was 84 years and the post-mortem interval before fixation was 5.6–8.2 h. Control samples (1 M, 2F) had no clinical neurological diagnosis, 1 sample had no post mortem neuropathological diagnosis, 1 had a pathological diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease, and 1 was diagnosed with Lewy Body Disease in the brainstem. Mean age at death was 86.7 years and the post mortem interval was between 7.8–9.8 h.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used in this study: rabbit polyclonal anti-AQP4 (Sigma, cat # SAB5200112), goat polyclonal anti-AQP4 (Santa Cruz, cat # sc9888), chicken polyclonal anti-GFAP for staining astrocyte processes (Millipore, cat # AB5541), mouse monoclonal 6E10 anti-Aβ (Eurogentec, cat # SIG-39320), rabbit polyclonal Iba-1 for staining microglia (Wako, cat # 019–19,741), rabbit polyclonal anti-NeuN for staining neurons (Millipore, cat # ABN78), and rabbit monoclonal anti-synaptophysin for identification of pre-synaptic dystrophies (Abcam, cat # ab52636). Alexa 488, 555 or 647 conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used for detection.

Immunostaining

5-μm thick microtome sections were cut from paraffin-embedded samples and mounted on glass slides. Sections were allowed to dry for at least 48 h after sectioning, then deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in a dilution series of water in ethanol. Antigen recovery was performed by placing slides in boiling 10 mM citrate, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 6.0 and allowing them to cool for 30 min. Slides were then equilibrated in PBS and blocked in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Slides were stained with primary antibodies in 1 μg/ml in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature, rinsed 3 times with PBS, then stained with secondary antibodies at 1 μg/ml in blocking buffer. Slides were then washed 5 times in PBS with a 5 min interval for each wash, then mounted under coverslips in ProLong Gold antifade. For thioflavin S staining, samples were incubated in a 1% solution of thioflavin S in PBS for 5 min following antibody staining. Samples were then washed 5 times in PBS with a 5 min incubation between each wash, prior to mounting.

Microscopy and image analysis

Sections were imaged with a Nikon C1 confocal microscope using 4x NA0.15, 20x NA0.5 or 100x NA1.4 objectives. For 3-color imaging, samples were scanned sequentially with the 488 nm, 561 nm and 647 nm lasers to ensure minimal crosstalk between channels. Analysis of plaque size and number was done using FIJI software. 20x images of Aβ staining from brain cortex were intensity-thresholded and objects greater than 50 μm2 were counted and measured for size. Plaque morphological analysis was done by comparing the relative staining intensity of immunolabeled Aβ and thioflavin S. For measurement of the density of glial processes in and around plaques, 100x images of GFAP and Aβ labeled sections were used. Aβ images were blurred with a Gaussian filter of 2 μm radius and thresholded to define the plaque boundary. A peri-plaque region extending 5 μm around the plaque was then created using the ‘make band’ function in FIJI. The average GFAP intensity in these 2 areas was then determined for each plaque and normalized to the average GFAP intensity in the surrounding field of view. The number of Iba1-positive cells was determined by intensity thresholding and automated counting; for measurement of plaque microglial coverage, the plaque perimeter and the length of microglial processes associated with the perimeter were measured manually. For measurement of neuronal Aβ uptake, the fraction of NeuN-positive cells containing 3 or more Aβ labeled puncta surrounding plaques was calculated. For measurement of AQP4 polarization, the background corrected mean fluorescence intensity of AQP4 labeling was determined within manually drawn ROIs in the perivascular or peri-plaque regions and divided by the mean intensity within non-plaque parenchymal areas.

Super-resolution microscopy

dSTORM imaging of paraffin sections from 5xFAD mice, where astrocyte processes were labeled with anti-GFAP antibody and Alexa 647 labeled secondary antibody, was performed as described previously [43].

Statistical analysis

Data was collated in Microsoft Excel. Statistical tests and graphing were performed with GraphPad Prism v. 5.01.

Results

Increased plaque size but reduced compact amyloid in 5xFAD mice lacking AQP4

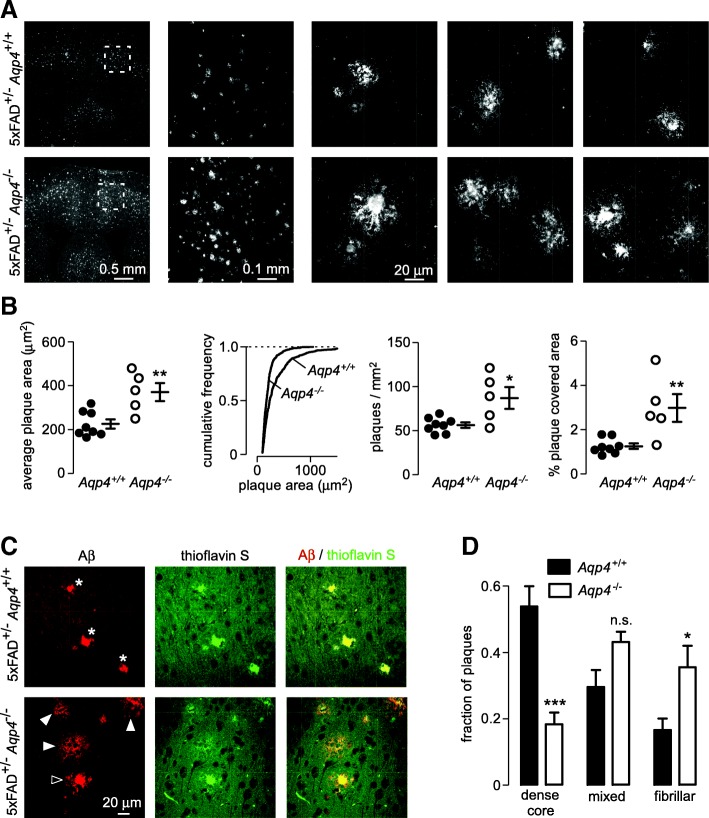

To investigate the effect of Aqp4 deletion on amyloid deposition in the brain we generated 5xFAD mice that lacked Aqp4 and aged them for 7–9 months before sacrifice. Staining of coronal sections with antibodies to Aβ revealed increased amyloid deposition in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1a). To quantify amyloid deposition, intensity-based thresholding and automated object counting were used to compare the size and number of plaques in individual mice. Analysis of the average plaque size and frequency distribution of plaque sizes showed significantly greater plaque size in the absence of AQP4 (Fig. 1b left and center left panels). The number of plaques in cerebral cortex was significantly greater in the Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice, which in combination with increased plaque size resulted in a more than 2-fold increase in total amyloid deposition (Fig. 1b center right and right panels).

Fig. 1.

Increased amyloid accumulation and more fibrillar plaques in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice. a Distribution of immunolabeled Aβ plaques in the brain of Aqp4 deficient and wild-type 5xFAD littermate at low and intermediate magnifications, and representative high magnification images of individual plaques. b Average plaque size in each mouse (left panel), cumulative plaque size distribution of all amyloid plaques in 5xFAD mice of each genotype, (center left panel), density of plaques in cortex (center right panel) and total amyloid load (right panel), as determined by intensity thresholding and automated object counting. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 by unpaired t-test. Lines show mean and S.E.M. of each genotype, n = 8 Aqp4+/+ and 5 Aqp4−/− mice. c Aβ immunolabeling and thioflavin S staining showing dense core (asterisk), fibrillar (solid arrow) or mixed (open arrow) plaques. d Fraction of plaques in each class. *** p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, n.s p > 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test

Amyloid plaques are classically described as dense-cored, fibrillar or diffuse based on morphological criteria and affinity for dyes that bind β-pleated sheets such as thioflavin S [10, 14]. We found that plaques from 5xFAD mice could be classified as dense-cored, fibrillar or mixed (compact core with fibrillary ‘halo’) with compact plaque cores showing very bright thioflavinS labeling and fibrillary plaques showing weaker thioflavin S labeling. Classical diffuse plaques, which have no thioflavinS labeling and no associated neuritic damage, were not seen in the 5xFAD mice. We found significantly more fibrillar plaques and significantly fewer dense core plaques in the Aqp4 knockout 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1d), indicating an altered amyloid accumulation pattern in the absence of AQP4.

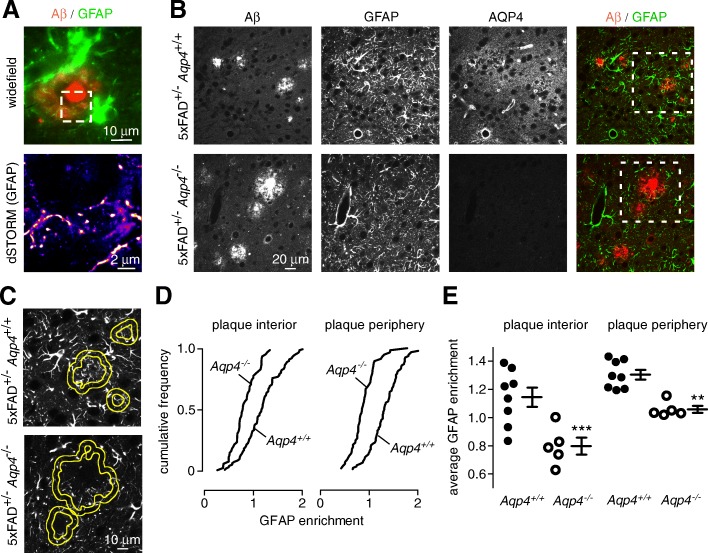

AQP4 is required for enrichment of astrocyte processes within and around plaques

Astrocytes and microglia form a reactive glial net around plaques [6]. By super-resolution microscopy a fine web of GFAP-labeled processes was seen surrounding plaque cores in wild-type 5xFAD mice (Fig. 2a). As AQP4 facilitates astrocyte migration and glial scar formation at sites of brain injury [39], we investigated the effect of Aqp4 deletion on the arrangement of astrocyte processes surrounding plaques.

Fig. 2.

Reduced peri-plaque astrocyte coverage in AQP4 deficient 5xFAD mice. a Super-resolution imaging demonstrates a mesh of GFAP labeled processes surrounding the plaque core in a wild-type 5xFAD mouse. b Aβ, GFAP and AQP4 immunofluorescence showing astrocyte processes around and within plaques of Aqp4+/+ and Aqp4−/− 5xFAD mice. The dotted square area denote the region shown in c. c Boundaries of segmented plaque interior and plaque periphery ROIs (yellow) superimposed on the corresponding GFAP image of astrocyte processes used to determine the extent to which astrocytes surround and infiltrate plaques. d GFAP enrichment, defined as average GFAP intensity within the indicated area divided by average GFAP intensity in the surrounding field of view, from within (‘plaque interior’) and around (‘plaque periphery’) plaques displayed as the cumulative frequency for all plaques from Aqp4+/+ and Aqp4−/− 5xFAD mice. e Average GFAP enrichment within and around plaques for all measured plaques in each individual Aqp4+/+ or Aqp4−/− 5xFAD mouse (Aqp4+/+ n = 8, Aqp4−/− n = 5; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 by unpaired t-test)

Immunofluorescence in Fig. 2b shows that GFAP-positive processes surround and invade plaques in wild-type 5xFAD mice; however, GFAP labeled processes were less prominent inside and around plaques in Aqp4 knockout 5xFAD mice. The extent of GFAP labeling inside and around plaques was quantified by intensity thresholding to identify plaque and peri-plaque regions of interest (Fig. 2c). GFAP labeling was increased in both the plaque interior and peri-plaque regions in wild-type 5xFAD mice when compared with the remaining, non-plaque-containing field of view. In the absence of AQP4, the GFAP labeling intensity in both the plaque interior and peri-plaque regions was significantly reduced compared to the non-plaque area (Fig. 2d, e). These results suggest the involvement of AQP4 in remodeling astrocyte processes around amyloid plaques.

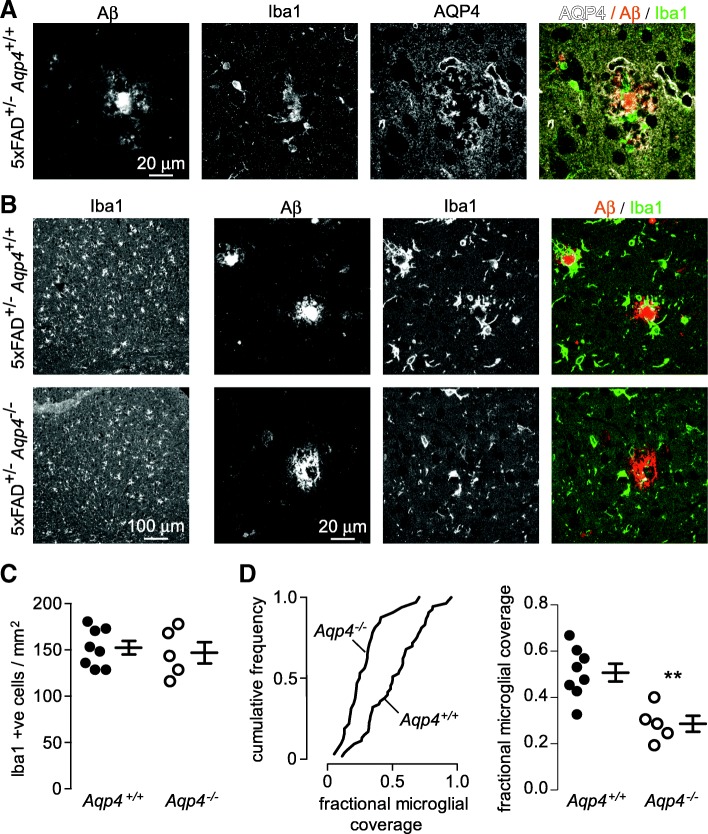

Reduced microglial recruitment to plaques in AQP4 deficient 5xFAD mice

Motivated by the importance of microglia in degrading Aβ [28] and forming compact plaque cores [13, 57], we investigated the effect of Aqp4 deletion on the microglial response in 5xFAD mice. Immunofluorescence with antibodies to Aβ, Iba1 and AQP4 from a wild-type, 5xFAD mouse showed AQP4-enriched astrocyte processes surrounding both plaque and plaque-associated microglia (Fig. 3a). Iba1 staining in wild-type and Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice was compared to determine if Aqp4 deletion disrupted peri-plaque microglial organization. Low magnification images (Fig. 3b left; Fig. 3c) show similar numbers of Iba1-positive cells in wild-type and Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice. At higher magnification, microglia in wild-type mice were seen to surround and contain plaques either completely or partially; however, microglia did not form an effective barrier around plaques in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice (Fig. 3b). The fraction of the plaque perimeter bounded by microglia was significantly reduced in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Reduced microglial plaque coverage in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice. a Aβ, Iba1 and AQP4 immunofluorescence showing close association peri-plaque AQP4-labeled astrocyte processes and Iba1-labeled microglia in wild-type 5xFAD mouse. b Low (left panels) and high (right panels) magnification images of Iba1-labeled microglia surrounding plaques in Aqp4+/+ and Aqp4−/− 5xFAD mice. c Average number of Iba1-expressing cells in cortex of Aqp4+/+ and Aqp4−/− 5xFAD mice as determined by thresholding and object counting (difference not significant). d Fractional coverage of plaque cores with Iba1-labeled microglial processes displayed as a frequency distribution for all plaques from Aqp4+/+ and Aqp4−/− 5xFAD mice (left panel). Average extent of plaque containment by microglia as determined for at least 10 plaques in each individual mouse (right panel). (Aqp4+/+ n = 8, Aqp4−/− n = 5, **p < 0.01 by unpaired t-test)

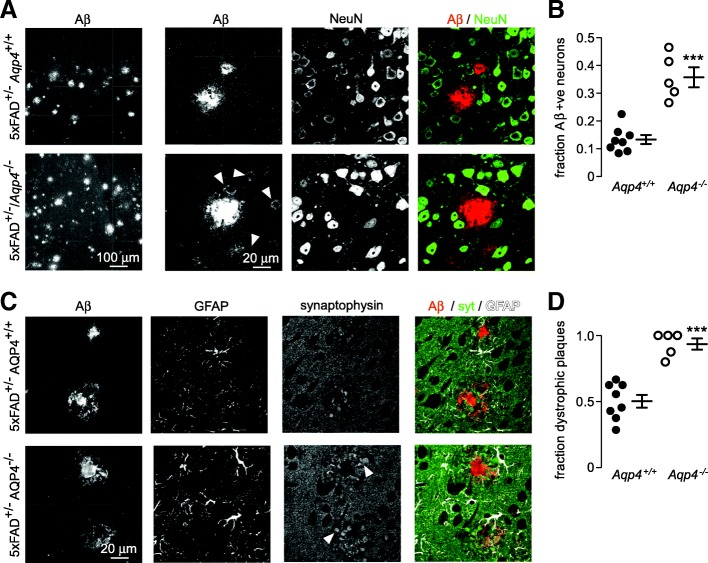

Increased intraneuronal Aβ in AQP4 deficient 5xFAD mice

Accelerated cognitive decline has been reported in AQP4 deficient APP/PS1 mice [55] and intraneuronal Aβ deposits are associated with neuron loss and cognitive deficit [11, 51]. Extensive uptake of Aβ by cells in the vicinity of plaques was visible in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice (Fig. 4a left panels, arrowheads), which by co-staining with the neuronal marker NeuN identified these cells as neurons (Fig. 4a, right). The fraction of neurons around plaques with punctate Aβ staining was markedly increased in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice (Fig. 4b). The formation of dystrophic neurites around plaques is another feature of Aβ mediated neurotoxicity [18]. The density of presynaptic dystrophies surrounding plaques was visualized using the synaptic vesicle marker synaptophysin [25, 40] (Fig. 4c, arrowheads). The fraction of neuritic plaques containing four or more large presynaptic dystrophies was much greater in the absence of AQP4 (Fig. 4d), further supporting the conclusion that disorganization of the peri-plaque glial net results in increased toxicity to surrounding neurons.

Fig. 4.

Increased neuronal Aβ uptake and more peri-plaque dystrophic neurites in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice. a Intermediate (left panels) and high (right panels) magnification images showing Aβ uptake in NeuN-labeled neurons surrounding plaques (arrowheads). b The fraction of Aβ-positive neurons surrounding plaques as measured in at least 10 separate plaques from each mouse of each genotype (Aqp4+/+ n = 8, Aqp4−/− n = 5, *** p < 0.001 by unpaired t-test). c Synaptophysin labeled presynaptic dystrophies (arrowheads) surrounding plaques showing increased peri-plaque dystrophies in Aqp4 deficient 5xFAD mice. d The fraction of dystrophic plaques (4 or more large presynaptic dystrophies) determined in 8–10 plaques from each mouse (Aqp4+/+ n = 8, Aqp4−/− n = 5, *** p < 0.001 by unpaired t-test)

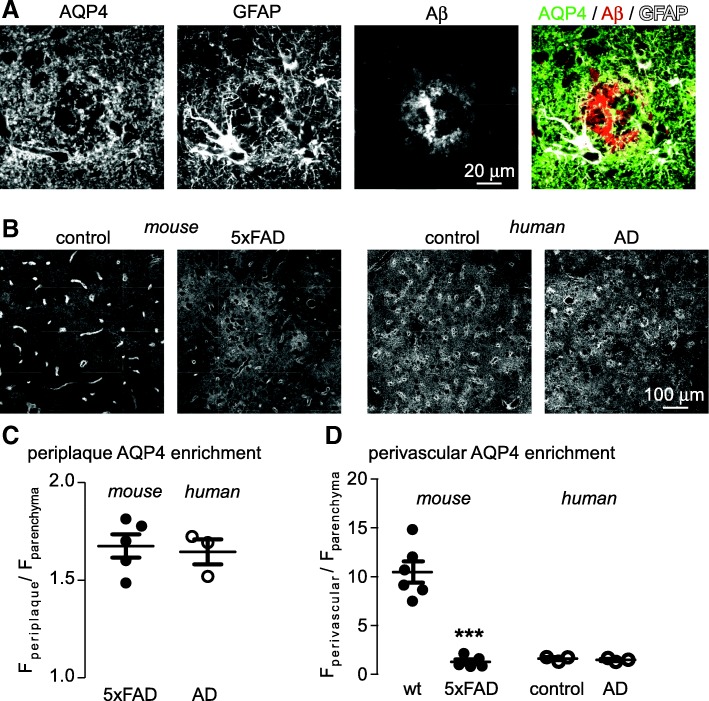

AQP4 distribution in human AD

Redistribution of AQP4 away from endfeet has been reported in rodent models of AD [50, 56]; however, in human brain the basal polarization of AQP4 to endfeet is far less dramatic and only small disease-associated changes in endfoot AQP4 have been suggested [16, 58]. We investigated AQP4 distribution in post-mortem samples of the inferior frontal gyrus from patients with diagnosed AD and age-matched controls without AD. In the AD brain, AQP4 was enriched in the peri-plaque processes of reactive astrocytes (Fig. 5a, c), as was observed in mice (Fig. 2a). In rodent AD, AQP4 was clearly redistributed away from endfeet (Fig. 5b, left, Fig. 5d); however, this was not observed in human brain, where AQP4 was not as heavily polarized in control samples (Fig. 5b right). These results demonstrate that the enrichment of AQP4 in peri-plaque astrocyte processes as described herein is relevant to human AD; however, the dramatic redistribution of AQP4 away from endfeet observed in mouse AD models is not observed in human, due to lower basal AQP4 levels in endfeet.

Fig. 5.

AQP4 is increased in peri-plaque astrocyte processes in post-mortem samples from human AD patients. a AQP4, GFAP and Aβ immunofluorescence in inferior frontal gyrus of a human AD patient showing AQP4 enrichment in peri-plaque astrocyte processes. b Lower magnification images showing extensive redistribution of AQP4 away from endfeet in 5xFAD mice compared to age matched wild-type mice, and corresponding images from aged control and AD human patient samples, demonstrating that AQP4 is mostly parenchymal in both cases. c Average enrichment of AQP4 in peri-plaque astrocyte processes, as compared to non-plaque parenchymal areas, in mouse and human AD. d Average enrichment of AQP4 in perivascular regions, compared to the parenchyma, in mouse and human control and AD. Samples from 6 wild-type and 5 5xFAD mice were compared along with 3 control samples and 3 AD human samples. (*** p < 0.001 by unpaired t-test)

Discussion

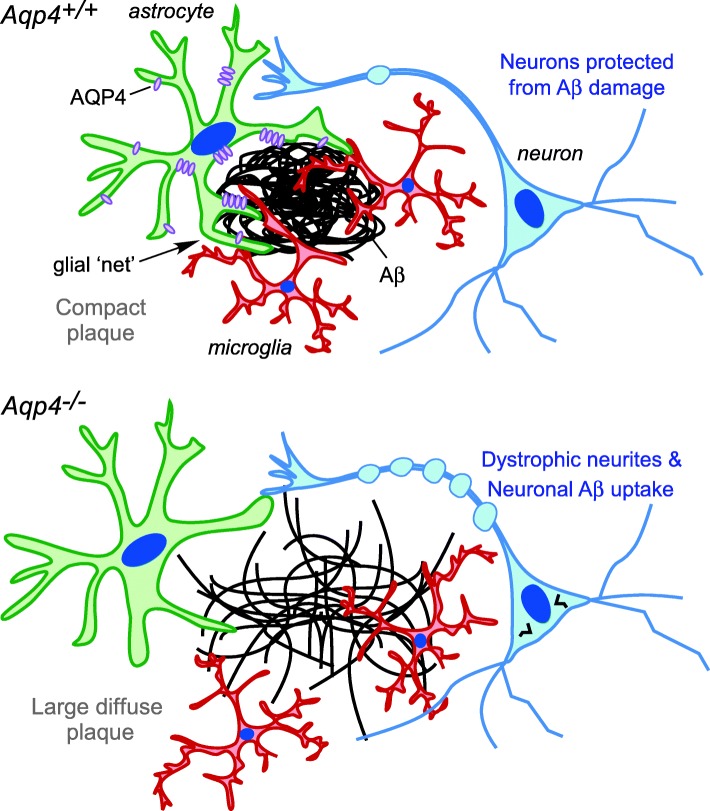

Our data here that Aqp4 deletion increases amyloid deposition in a mouse model of AD is in agreement with prior reports [55], but challenge the prevailing notion that the increased amyloid is a consequence of reduced Aβ clearance due to loss of perivascular AQP4 [22]. Instead, we found that Aqp4 deletion markedly impairs peri-plaque astrocyte structural organization and the recruitment of microglia to plaques. This is associated with an increase in the number of fibrillar plaques and consequent greater damage to neurons surrounding plaques, which can account for the reported worsening of cognitive signs in Aqp4 deficient AD model mice [55]. On the basis of these results we propose a novel mechanistic model to account for the role of AQP4 in amyloid accumulation (Fig. 6). According to this model, increased expression of AQP4 in glial processes occurs in response to the initial formation of insoluble amyloid aggregates, which facilitates structural rearrangements in astrocytes and the recruitment of microglia to plaques. The resulting physical barrier helps to segregate plaques from the surrounding tissue.

Fig. 6.

Proposed role of AQP4 in containment of amyloid plaques and recruitment of microglia. When AQP4 is present, its redistribution to peri-plaque astrocyte processes is associated with formation of a glial net surrounding the plaque, recruitment of microglia, and partial protection of nearby neurons from the deleterious effects of Aβ aggregates. In AQP4 deficiency, astrocytes fail to contain plaques or recruit microglia, resulting in large fibrillar plaques that cause greater damage to nearby neurons

An increase in amyloid plaque accumulation in AD can potentially be attributed to impaired Aβ clearance, increased Aβ production, or a greater propensity for soluble Aβ to incorporate in plaques. Clearance of Aβ monomers may occur by degradation (25–50%), transport across the blood brain barrier (25–40%), or bulk clearance into the CSF (~ 10%) [9, 20, 45]. Iliff et al. [23] reported that clearance of injected Aβ from the brain was sensitive to Aqp4 deletion, and proposed a role for AQP4 in bulk clearance. However, the time course of clearance was more rapid than that of other markers such as inulin that are cleared by a bulk clearance mechanism [20]. We did not find significantly altered distribution of injected Aβ in Aqp4 deficient mice [44], which suggests that increased amyloid accumulation in Aqp4 deficient mice is unlikely to be explained by impaired clearance. Since presynaptic dystrophies are major sites of Aβ synthesis [40], the increased number of dystrophic neurites in Aqp4 deficient AD mice may increase amyloid accumulation and neuronal Aβ uptake. Additionally, incorporation of soluble Aβ into plaques is increased in regions that are not surrounded by glia [13]. Finally, plaque morphological alterations are also potentially a consequence of failure of peri-plaque glia to condense amyloid [57], although other explanations are possible.

We find that the density of astrocyte processes surrounding and within amyloid plaques is reduced in Aqp4 deficient AD mice. The presence of astrocyte processes in amyloid plaques from AD patients has been long recognized [15] and the barrier formed by astrocytes and microglia around plaques was recently described as a reactive glial net [6]. Deletion of astrocyte intermediate filament proteins that are involved in structural reorientation increases amyloid accumulation in mouse models of AD [26], suggesting a role for astrocyte structural reorganization in limiting amyloid accumulation. In addition to GFAP and AQP4, peri-plaque astrocyte processes are enriched in connexins [33], suggesting structural similarities to other glial barriers such as the glia limitans and glial scars formed following trauma. The observation here that AQP4 participates in reorientation of astrocytic processes toward plaques is consistent with previous observations that AQP4 facilitates extension of astrocyte processes during their migration [42] and glial scar formation in response to trauma [39]. Mechanistically, this is thought to occur via coupling of solute and water uptake, which osmotically inflates the leading edge of extending processes and facilitates actin polymerization-driven extension [36].

An additional finding was impaired recruitment of microglia to plaques in Aqp4 deficient AD mice. Microglia phagocytose and degrade Aβ [28] and deletion of microglial chemokine receptors prevents microglial recruitment to plaques and increases amyloid deposition [17], similar to the changes observed here in Aqp4 deficient AD mice. Astrocytes are an important source of inflammatory cytokines in AD [29] and AQP4 deletion impairs release of proinflammatory cytokines by astrocytes [30, 31], suggesting that the failure of microglial accumulation around plaques in Aqp4 deficient AD mice might be a consequence of impaired astrocyte cytokine release. Although the mechanism of AQP4-dependent cytokine release is not known, Aqp4 deletion impairs astrocyte Ca2+ signaling [5, 47], which is involved in cytokine release [41]. Astroglial ApoE and liver X receptor are required for microglial Aβ phagocytosis [46], providing further evidence that interaction between astrocytes and microglia is required for efficient Aβ degradation. Also, perhaps altered plaque structure and/or failure to remodel the extracellular space in Aqp4 deficient mice could lead to failure of microglia to interact with plaques.

Aqp4 deletion was associated with an increase in the number of plaques surrounded by dystrophic neurites and an increase in the number of neurons containing Aβ aggregates. Although the cause of this is unclear, it may be related to impairment in plaque containment or to the greater amount of aggregated amyloid present in the mice lacking Aqp4. Neuritic damage associated with fibrillary plaques may be due to direct penetration of the neuronal membrane by extending amyloid fibrils in the absence of glial containment [13, 57]. Reactive astrocytes also play an important role in phagocytosis and degradation of dystrophic neurites. Since AQP4 is heavily enriched in the limiting membrane of astrocyte phagosomes [19], Aqp4 deletion may also impair clearance of damaged neurites from the peri-plaque area.

The marked enrichment of AQP4 in astrocyte endfeet and its redistribution to the parenchyma in mouse models of AD have led to speculation that loss of endfoot AQP4 may be an important cause of amyloid accumulation in the ageing brain due to impairment of the ‘glymphatic’ system [27]. However, the extent of AQP4 enrichment in endfeet in human brain is much less than in rodents [16] and the extent of AQP4 redistribution in human AD is very limited [58], calling into question the relevance of findings from mouse models to human AD. In agreement with these findings we were unable to find any indication of AQP4 redistribution from endfeet to the non-plaque parenchyma in a limited number of human AD samples. We did, however, find that AQP4 was enriched within the peri-plaque glial net surrounding plaques from human AD patients to the same extent as in the mouse model, suggesting that AQP4 mediated remodeling of peri-plaque astrocyte processes is relevant to the human disease.

Conclusions

In summary, our results support a novel role for AQP4 in the pathology of AD and highlight the importance of the peri-plaque glial environment as a determinant of amyloid neurotoxicity. Further understanding of the role of astrocyte water transport in formation of glial barriers is therefore expected to identify novel therapeutic approaches that can enhance endogenous protective mechanisms that limit amyloid neuropathology in AD.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

This work was supported by grant A2018351S from the ADR program of the BrightFocus Foundation and NIH grant EY029881 to AJS and by NIH grants EY013574 and EB000415 to ASV. Human tissue samples were provided by the Neurodegenerative Disease Brain Bank at the University of California, San Francisco, which receives funding support from NIH grants P01AG019724 and P50AG023501, the Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research, and the Tau Consortium.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 5xFAD

Mouse containing transgenes with 5 familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- AQP4

Aquaporin-4 (human gene)

- Aqp4

Aquaporin-4 (mouse gene)

- AQP4

Aquaporin-4 (protein)

- Aβ

β amyloid

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- dSTORM

direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- MMRC

Mutant mouse resource center

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PSEN1

Presenilin 1

- ROI

Region of interest

Authors’ contributions

AJS and TD performed all experiments. AJS and ASV designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Procedures for tissue donation and distribution by the UCSF NDBB are approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board. All animal procedures were approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Albargothy NJ, Johnston DA, MacGregor-Sharp M, Weller RO, Verma A, Hawkes CA, Carare RO. Convective influx/glymphatic system: tracers injected into the CSF enter and leave the brain along separate periarterial basement membrane pathways. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:139–152. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1862-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asgari M, de Zelicourt D, Kurtcuoglu V. Glymphatic solute transport does not require bulk flow. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38635. doi: 10.1038/srep38635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auguste KI, Jin S, Uchida K, Yan D, Manley GT, Papadopoulos MC, Verkman AS. Greatly impaired migration of implanted aquaporin-4-deficient astroglial cells in mouse brain toward a site of injury. FASEB J. 2007;21:108–116. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6848com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben Haim L, Carrillo-de Sauvage MA, Ceyzeriat K, Escartin C. Elusive roles for reactive astrocytes in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:278. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benfenati V, Caprini M, Dovizio M, Mylonakou MN, Ferroni S, Ottersen OP, Amiry-Moghaddam M. An aquaporin-4/transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (AQP4/TRPV4) complex is essential for cell-volume control in astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2563–2568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012867108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouvier DS, Jones EV, Quesseveur G, Davoli MA, A Ferreira T, Quirion R, Mechawar N, Murai KK. High resolution dissection of reactive glial nets in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24544. doi: 10.1038/srep24544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burfeind KG, Murchison CF, Westaway SK, Simon MJ, Erten-Lyons D, Kaye JA, Quinn JF, Iliff JJ. The effects of noncoding aquaporin-4 single-nucleotide polymorphisms on cognition and functional progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2017;3:348–359. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carare RO, Bernardes-Silva M, Newman TA, Page AM, Nicoll JA, Perry VH, Weller RO. Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34:131–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carare RO, Hawkes CA, Jeffrey M, Kalaria RN, Weller RO. Review: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, prion angiopathy, CADASIL and the spectrum of protein elimination failure angiopathies (PEFA) in neurodegenerative disease with a focus on therapy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:593–611. doi: 10.1111/nan.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chlan-Fourney J, Zhao T, Walz W, Mousseau DD. The increased density of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-immunoreactive microglia in the sensorimotor cortex of aged TgCRND8 mice is associated predominantly with smaller dense-core amyloid plaques. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1433–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen DZ, Kraus SL, Flohr A, Cotel MC, Wirths O, Bayer TA. Transient intraneuronal a beta rather than extracellular plaque pathology correlates with neuron loss in the frontal cortex of APP/PS1KI mice. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:647–655. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun H, Lee CJ. Reactive astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: a double-edged sword. Neurosci Res. 2018;126:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condello C, Yuan P, Schain A, Grutzendler J. Microglia constitute a barrier that prevents neurotoxic protofibrillar Abeta42 hotspots around plaques. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6176. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson TC, Vickers JC. The morphological phenotype of beta-amyloid plaques and associated neuritic changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2001;105:99–107. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffy PE, Rapport M, Graf L. Glial fibrillary acidic protein and Alzheimer-type senile dementia. Neurology. 1980;30:778–782. doi: 10.1212/WNL.30.7.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eidsvaag VA, Enger R, Hansson HA, Eide PK, Nagelhus EA. Human and mouse cortical astrocytes differ in aquaporin-4 polarization toward microvessels. Glia. 2017;65:964–973. doi: 10.1002/glia.23138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Khoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, Means TK, Terada K, Geula C, Luster AD. Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:432–438. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiala JC. Mechanisms of amyloid plaque pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:551–571. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Arboledas A, Davila JC, Sanchez-Mejias E, Navarro V, Nunez-Diaz C, Sanchez-Varo R, Sanchez-Mico MV, Trujillo-Estrada L, Fernandez-Valenzuela JJ, Vizuete M, Comella JX, Galea E, Vitorica J, Gutierrez A. Phagocytic clearance of presynaptic dystrophies by reactive astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease. Glia. 2018;66:637–653. doi: 10.1002/glia.23270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Elimination of substances from the brain parenchyma: efflux via perivascular pathways and via the blood-brain barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2018;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s12987-018-0113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holter KE, Kehlet B, Devor A, Sejnowski TJ, Dale AM, Omholt SW, Ottersen OP, Nagelhus EA, Mardal KA, Pettersen KH. Interstitial solute transport in 3D reconstructed neuropil occurs by diffusion rather than bulk flow. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:9894–9899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706942114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1299–1309. doi: 10.1172/JCI67677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iliff J. J., Wang M., Liao Y., Plogg B. A., Peng W., Gundersen G. A., Benveniste H., Vates G. E., Deane R., Goldman S. A., Nagelhus E. A., Nedergaard M. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid . Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(147):147ra111–147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin BJ, Smith AJ, Verkman AS. Spatial model of convective solute transport in brain extracellular space does not support a “glymphatic” mechanism. J Gen Physiol. 2016;148:489–501. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201611684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandalepas PC, Sadleir KR, Eimer WA, Zhao J, Nicholson DA, Vassar R. The Alzheimer’s beta-secretase BACE1 localizes to normal presynaptic terminals and to dystrophic presynaptic terminals surrounding amyloid plaques. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:329–352. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1152-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraft AW, Hu X, Yoon H, Yan P, Xiao Q, Wang Y, Gil SC, Brown J, Wilhelmsson U, Restivo JL, Cirrito JR, Holtzman DM, Kim J, Pekny M, Lee JM. Attenuating astrocyte activation accelerates plaque pathogenesis in APP/PS1 mice. FASEB J. 2013;27:187–198. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-208660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, Wang M, Wei HS, Zeppenfeld D, Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Liew JA, Plog BA, Ding F, Deane R, Nedergaard M. Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:845–861. doi: 10.1002/ana.24271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee CY, Landreth GE. The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2010;117:949–960. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Zhao R, Gao K, Wei Z, Yin MY, Lau LT, Chui D, Yu AC. Astrocytes: implications for neuroinflammatory pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:67–80. doi: 10.2174/156720511794604543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Zhang H, Varrin-Doyer M, Zamvil SS, Verkman AS. Proinflammatory role of aquaporin-4 in autoimmune neuroinflammation. FASEB J. 2011;25:1556–1566. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Zhang H, Verkman AS. Greatly attenuated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in aquaporin-4 knockout mice. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Generation and phenotype of a transgenic knockout mouse lacking the mercurial-insensitive water channel aquaporin-4. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:957–962. doi: 10.1172/JCI231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mei X, Ezan P, Giaume C, Koulakoff A. Astroglial connexin immunoreactivity is specifically altered at beta-amyloid plaques in beta-amyloid precursor protein/presenilin1 mice. Neuroscience. 2010;171:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen HM, Veerhuis R, Holmqvist B, Janciauskiene S. Binding and uptake of a beta1-42 by primary human astrocytes in vitro. Glia. 2009;57:978–988. doi: 10.1002/glia.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, Berry R, Vassar R. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S, Verkman AS. Aquaporins and cell migration. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rainey-Smith SR, Mazzucchelli GN, Villemagne VL, Brown BM, Porter T, Weinborn M, Bucks RS, Milicic L, Sohrabi HR, Taddei K, Ames D, Maruff P, Masters CL, Rowe CC, Salvado O, Martins RN, Laws SM, AIBL Research Group Genetic variation in Aquaporin-4 moderates the relationship between sleep and brain Abeta-amyloid burden. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:47. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rash JE, Yasumura T, Hudson CS, Agre P, Nielsen S. Direct immunogold labeling of aquaporin-4 in square arrays of astrocyte and ependymocyte plasma membranes in rat brain and spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11981–11986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Watanabe H, Yan D, Manley GT, Verkman AS. Involvement of aquaporin-4 in astroglial cell migration and glial scar formation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5691–5698. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadleir KR, Kandalepas PC, Buggia-Prevot V, Nicholson DA, Thinakaran G, Vassar R. Presynaptic dystrophic neurites surrounding amyloid plaques are sites of microtubule disruption, BACE1 elevation, and increased Abeta generation in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:235–256. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1558-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shirakawa H, Katsumoto R, Iida S, Miyake T, Higuchi T, Nagashima T, Nagayasu K, Nakagawa T, Kaneko S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induces ca(2+) signaling and CXCL1 release via TRPC6 channel in astrocytes. Glia. 2017;65:1005–1016. doi: 10.1002/glia.23141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith AJ, Jin BJ, Ratelade J, Verkman AS. Aggregation state determines the localization and function of M1- and M23-aquaporin-4 in astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:559–573. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith AJ, Verkman AS. Superresolution imaging of Aquaporin-4 cluster size in antibody-stained paraffin brain sections. Biophys J. 2015;109:2511–2522. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith AJ, Yao X, Dix JA, Jin BJ, Verkman AS. Test of the ‘glymphatic’ hypothesis demonstrates diffusive and aquaporin-4-independent solute transport in rodent brain parenchyma. eLife. 2017;6:27679. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E, Axel L, Rusinek H, Nicholson C, Zlokovic BV, Frangione B, Blennow K, Menard J, Zetterberg H, Wisniewski T, de Leon MJ. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:457–470. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terwel D, Steffensen KR, Verghese PB, Kummer MP, Gustafsson JA, Holtzman DM, Heneka MT. Critical role of astroglial apolipoprotein E and liver X receptor-alpha expression for microglial Abeta phagocytosis. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7049–7059. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6546-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thrane AS, Rappold PM, Fujita T, Torres A, Bekar LK, Takano T, Peng W, Wang F, Rangroo Thrane V, Enger R, Haj-Yasein NN, Skare O, Holen T, Klungland A, Ottersen OP, Nedergaard M, Nagelhus EA. Critical role of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) in astrocytic Ca2+ signaling events elicited by cerebral edema. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015217108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verbavatz JM, Ma T, Gobin R, Verkman AS. Absence of orthogonal arrays in kidney, brain and muscle from transgenic knockout mice lacking water channel aquaporin-4. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 22):2855–2860. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.22.2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verkhratsky A, Parpura V, Pekna M, Pekny M, Sofroniew M. Glia in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:1291–1301. doi: 10.1042/BST20140107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilcock DM, Vitek MP, Colton CA. Vascular amyloid alters astrocytic water and potassium channels in mouse models and humans with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2009;159:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson EN, Abela AR, Do Carmo S, Allard S, Marks AR, Welikovitch LA, Ducatenzeiler A, Chudasama Y, Cuello AC. Intraneuronal amyloid Beta accumulation disrupts hippocampal CRTC1-dependent gene expression and cognitive function in a rat model of Alzheimer disease. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27:1501–1511. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wyss-Coray T, Loike JD, Brionne TC, Lu E, Anankov R, Yan F, Silverstein SC, Husemann J. Adult mouse astrocytes degrade amyloid-beta in vitro and in situ. Nat Med. 2003;9:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nm838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyss-Coray T, Rogers J. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease-a brief review of the basic science and clinical literature. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006346. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, O'Donnell J, Christensen DJ, Nicholson C, Iliff JJ, Takano T, Deane R, Nedergaard M. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Z, Xiao N, Chen Y, Huang H, Marshall C, Gao J, Cai Z, Wu T, Hu G, Xiao M. Deletion of aquaporin-4 in APP/PS1 mice exacerbates brain Abeta accumulation and memory deficits. Mol Neurodegener. 2015;10:58. doi: 10.1186/s13024-015-0056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Lunde LK, Nuntagij P, Oguchi T, Camassa LM, Nilsson LN, Lannfelt L, Xu Y, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Ottersen OP, Torp R. Loss of astrocyte polarization in the tg-ArcSwe mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:711–722. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yuan P, Condello C, Keene CD, Wang Y, Bird TD, Paul SM, Luo W, Colonna M, Baddeley D, Grutzendler J. TREM2 Haplodeficiency in mice and humans impairs the microglia barrier function leading to decreased amyloid compaction and severe axonal dystrophy. Neuron. 2016;92:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeppenfeld DM, Simon M, Haswell JD, D'Abreo D, Murchison C, Quinn JF, Grafe MR, Woltjer RL, Kaye J, Iliff JJ. Association of Perivascular Localization of Aquaporin-4 with cognition and Alzheimer disease in aging brains. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:91–99. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.