Abstract

Medical-legal partnership (MLP) is a health care delivery innovation that embeds civil legal aid expertise into the health care team to address health-harming legal needs for vulnerable populations at risk for poor health. The MLP approach focuses on prevention by addressing upstream structural and systemic social and legal problems that affect patient and population health. Because many unmet legal needs affect health (such as residing in substandard housing; wrongful denial of government income supports, health insurance, or food assistance; family violence; and barriers to care based on immigration status), lawyers are important members of the health care team. This review describes the MLP approach to addressing the social determinants of health, examines its benefits for improving the delivery of primary care for vulnerable patients and populations, and explores new opportunities for MLP in primary care with the advent of systems reforms driven by the Affordable Care Act.

Keywords: medical-legal, social determinants of health, vulnerable populations, primary care, health reform

‘In addition, many of the value-based health care delivery reforms that have been promoted since the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 focus on providing well-coordinated, patient-centered, preventive primary care for vulnerable patient populations . . .’

Introduction

Growing attention to the ways in which the social determinants of health (SDH)— the conditions in which people live, learn, work, and play—are inextricably woven into and affect individual and population health is leading to a range of health care system innovations. Health system administrators, providers, payers, and policymakers are recognizing that to reduce health care costs, particularly for high utilizing patients, and to improve patient and population health outcomes, health care delivery must extend beyond medicine to include social, legal, and other community-based supports. In addition, many of the value-based health care delivery reforms that have been promoted since the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 (ACA) focus on providing well-coordinated, patient-centered, preventive primary care for vulnerable patient populations through a team-based approach that incorporates attention to the SDH.

Medical-legal partnership (MLP) is a health care delivery innovation that started in the early 1990s and is now rapidly expanding across the country, with programs in nearly 300 health centers and hospitals in 41 states.1 The MLP approach embeds civil legal aid expertise into the health care team to address health-harming legal needs for low-income populations at risk for poor health. The MLPs focus on prevention by addressing upstream structural and systemic social and legal problems that affect patient and population health. Because many unmet legal needs affect health (such as residing in substandard housing; wrongful denial of government income supports, health insurance, or food assistance; family violence; and barriers to care based on immigration status), lawyers are important members of the health care team.

Studies are indicating the effectiveness of the MLP approach for addressing the quadruple aim of enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and improving the experience of health care providers.2 This review describes the MLP approach to addressing the SDH, examines its benefits for improving the delivery of primary care for vulnerable patients and populations, and explores new opportunities for MLP with the advent of systems reforms driven by the ACA.

Social Needs and Health

It is well documented that social, environmental, and economic forces shape individual and community health outcomes.3 It is estimated that at least 60% of health outcomes are attributable to forces outside of medical care.4 In the United States, health disparities persist across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups,5 and the United States continues to rank lower on population health outcomes, including maternal mortality, life expectancy, and low birth weight, compared with the other 34 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).6

Elizabeth Bradley and Lauren Taylor point out that, whereas the United States spends nearly 18% of GDP on medical care, other OECD countries spend an average of 11% and achieve significantly better population health outcomes. They attribute the better outcomes in these other countries, in part, to the higher percentage of GDP spent in these other countries on social services. The United States spends 90 cents for every dollar spent on medical care, whereas OECD countries with better health outcomes spend 2 dollars on social services for every dollar spent on medical care.6 States in the United States that have a higher ratio of social and public health spending to health care spending have better health outcomes.7

Recognition of the importance of the impact of adverse social conditions on health has led to a range of responses within the US health care system. These range from identification of social needs as part of health care screening,8 including recording of these needs in the electronic medical record (EMR),9 to investment in community health workers, whose role is to identify and address social needs as part of health care delivery,10 to integrated care models that seek to create links between clinics and community-based resources and services.11

Policymakers are also embracing the need to link the clinic to community resources. For example, in 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid announced the Accountable Health Communities model to address the “critical gap between clinical care and community services in the current health care delivery system by testing whether systematically identifying and addressing the health related social needs of beneficiaries impacts total health care costs, improves health and quality of life.” This demonstration project will help inform efforts to align clinical care with community supports related to social needs.12

Although connecting vulnerable patients and their families to social services is critical to improving health and well-being, systems barriers, including unmet legal needs, often stand in the way of successfully addressing patients’ social needs and achieving upstream prevention. In fact, the SDH are often created or influenced by laws that are inconsistent with health promotion, enforced unfairly, or are underenforced.13

Unmet Legal Needs and Health

One in 6 Americans—more than 43 million people in the United States—lives in poverty.14 Studies have consistently shown that the majority of low-income families experience some civil legal needs related to basic human needs, including access to government entitlements and health care, safe housing, the ability to secure appropriate education, and protection from family violence. It is estimated that most low-income individuals experience at least 2 legal needs and that these needs often go unaddressed or are resolved without legal assistance, undermining these individuals’ legal rights.15

Civil legal services lawyers provide no-cost assistance to low-income individuals in civil matters. Low income is generally defined as those living below 125% of the Federal Poverty Level. Unlike public defenders who provide assistance free of charge to indigent defendants, there is no guarantee of assistance in civil matters for low-income individuals.

It is estimated that existing legal aid programs meet less than 20% of the need of qualifying low-income individuals and families.14 Federal cuts to legal aid programs are exacerbating this crisis.16 Low-income individuals and families often endure significant hardships as a result of the inability to realize and enforce important legal rights. For example, failure to secure government benefits for which they are eligible or entitled (such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, cash assistance, Social Security Disability income, or housing subsidies) can result in food insecurity, homelessness, or utility shutoffs. Similarly, lack of enforcement of housing codes can jeopardize family health, safety, and stability.17 In fact, law is a significant SDH:

Law, as embodied in federal or state statutes, regulations, executive orders, administrative agency decisions, and court decisions, plays a profound role in shaping life circumstances, particularly as it relates to access, financing, and quality of individual health care.18

But just as law can serve as a barrier to health, it can also serve as a remedy to health-harming social needs. Laws can be written or interpreted to either help or hinder population health.19 Enforcement of existing laws can prevent harm to health; for example, proactive and systematic enforcement of housing codes can prevent significant harms to health, including lead poisoning, asthma, and injury.16

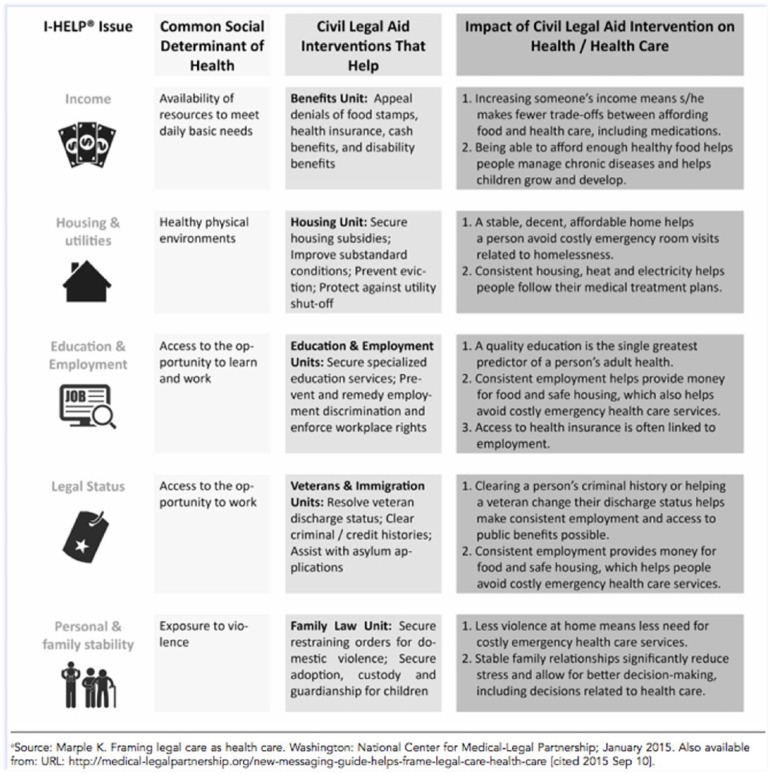

There has been attention in the past 20 years to the important correlation between legal needs and the SDH. A study of community health center patients estimated that the percentage of patients requiring assistance with health-related legal needs ranged from 50% to 85%. Uninsured patients, Medicaid patients, the disabled, and patients with chronic health conditions were most likely to require legal assistance.17 Figure 1 describes how civil legal interventions address the SDH.

Figure 1.

How Civil Legal Aid Helps Health Care Address the Social Determinants of Health.

The MLP Approach

The MLP approach addresses the correlation between unmet legal needs and health by embedding civil legal aid expertise into the health care team to address health-harming legal needs for low-income populations at risk for poor health and well-being. The MLP approach focuses on prevention by addressing upstream structural and systemic social and legal problems that affect population health. It leverages medical and legal resources through an interprofessional model of care delivery.

Through the MLP approach, hospitals and health centers partner with civil legal aid resources in their community to (1) train staff at the hospitals and health centers about how to identify health-harming legal needs, (2) treat health-harming legal needs through a variety of legal interventions, (3) transform clinic practice to treat both medical and social issues that affect a person’s health and well-being, and (4) improve population health by using combined health and legal tools to address widespread social problems, such as housing conditions, that negatively affect a population’s health and well-being.20

Training

Training the health care team to identify legal needs is the first step to integrating MLP into health care delivery for vulnerable populations. MLP education and training takes place in multiple settings and with a wide range of learners. For many years, MLPs have provided interprofessional education for law and medical students.21 Increasingly, MLP education is being expanded to include a number of disciplines, including nursing, public health, and social work.22

As health care reform efforts focus on interprofessional team-based care models, medical and health professions schools are building interprofessional education into their curricula. MLP education, both didactic and experiential, is playing a key role in these efforts.23 A recent report by the Association of American Medical Colleges, Achieving Health Equity: How Academic Medicine Is Addressing the Social Determinants of Health, highlights MLP as “particularly effective at addressing the social and economic determinants of health.”24

MLP also provides an ideal method to train residents to recognize the upstream structural and legal barriers that affect their patients’ health, as well as what physicians can do, in partnership with lawyers, to address these barriers.25 In fact, didactic and on-the-ground training in MLP help residents meet many of the competencies and milestones required through their specialties and supports residents’ development of structural competency,26 defined as follows:

the trained ability to discern how a host of issues defined clinically as symptoms, attitudes, or diseases (e.g., depression, hypertension, obesity, smoking, medication “non-compliance,” trauma, psychosis) also represent the downstream implications of a number of upstream decisions about such matters as health care and food delivery systems, zoning laws, urban and rural infrastructures, medicalization, or even about the very definitions of illness and health.27, (p128)

Screening

In addition to training health care team members, MLPs integrate screening for legal needs as part of health care delivery. Capacity and need determine which populations may be routinely screened by health care providers. Screening typically follows the I-HELP domains: Income, Housing, Education/employment, Legal status/immigration, and Personal and family stability. Although each MLP program may adopt its own screening tool,28 model tools have been created and may be adapted for local programs and contexts.29

With the growing use of the EMR, some health care institutions with MLPs are experimenting with ways to incorporate social and legal needs questions into the EMR in order to systematize provider screening.30 MLPs also create form letters for providers in the EMR to help them quickly and easily advocate for their patients to ensure compliance with a whole host of laws affecting patient health, including employment protections such as those under the Family and Medical Leave Act and Americans with Disabilities Act, protection from utility shutoffs and housing code violations, required services for children with disabilities under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and others.

Systems and Policy Change

To truly work upstream, MLPs do not just focus on helping individual patients and families, but they also detect and “treat” problems that affect communities and populations.

MLPs effectively link the public health system, health care delivery and legal and policy reforms.31 Because MLPs partner clinicians with lawyers and other professionals (eg, social workers, community health workers, pharmacists) and identify systemic failures that lead to downstream health outcomes, they serve to link patients to policy.

For example, by linking health care staff with lawyers, MLPs have mapped and addressed, through legal advocacy, systemic housing code violations affecting child health and leading to increased hospitalizations for low-income, predominantly African American children with asthma.32 By partnering health care providers and lawyers, they have successfully changed regulations affecting utility shutoff protection for low-income families and have helped rewrite city ordinances on lead safety, reducing the number of children poisoned in a community with a high prevalence of lead poisoning.33

The National MLP Movement

Since the first MLP was founded in 1993, the model’s growth was slow but steady for the first decade and then accelerated in the mid-2000s, with growing recognition that MLP is a key strategy for addressing the SDH. In 2006, the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership (NCMLP) was created to address the need for an infrastructure to support MLP research, best practices, and scaling. Today, more than 294 US hospitals and health centers in 41 states house an MLP, serving a range of diverse populations, including children, those who are disabled, the elderly, rural populations, veterans, refugees, and homeless individuals, among others.34 With greater recognition of the power of MLP for improving health for vulnerable patient populations it is receiving national attention among health policy makers as well as in the media.35

With passage of the ACA in 2010 and growing focus on the “quadruple aim”2—enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing health care costs, and improving provider experience—systematic evaluation of the impact of MLP on patients, population health, providers, and health care cost reduction is needed. Although no such systematic study of MLP impact has been completed to date, pilot studies provide preliminary evidence in 3 areas: patient health and well-being, knowledge and satisfaction of health providers in addressing the SDH, and systems improvement in and return on investment to health care institutions. Some of these studies are described below.

MLP Impact on Patients, Providers, and Institutions

Patients

Several studies have shown improved health and well-being for patients who receive legal interventions through MLP, including reduction in patient stress36 and improved health care compliance.37 Another study showed that targeted legal assistance directed at improving housing conditions led to improved health outcomes in asthma patients,38 and a study of children with sickle cell disease found improved health outcomes with MLP intervention.39

Studies also show that pairing MLP with other support services can render positive health outcomes. A study of integration of legal interventions into the Healthy Start home visiting program found improved pregnancy outcomes, lower rates of abuse and neglect, and better prenatal health behaviors for mothers receiving services.40 A randomized controlled trial in which intervention families with newborns received services through the Developmental Understanding and Legal Collaboration for Everyone program, which included MLP, found that intervention infants were more likely to have completed their 6-month immunization schedule by age 7 months and, by 8 months, were more likely to have had 5 or more routine preventive care visits by age 1 year and were less likely to have visited the emergency department by age 6 months.41

Other studies have focused on reduced health care use for patients receiving MLP services. One study found a 91% reduction in ER visits for adult asthma patients following MLP-related housing interventions.42 A pilot study in Pennsylvania testing the integration of MLP into the “superutilizer” team demonstrated a decrease in both 30-day and 7-day readmission rates. Emergency department use dropped nearly 50%, and overall costs (as defined by charges) fell by 45%.43

Providers

A 2011 study by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that 85% of physicians surveyed said that unmet social needs are directly leading to worse health outcomes, and 9 out of 10 physicians serving low-income populations said that addressing patients’ social needs is as important as addressing medical conditions. Yet 4 out of 5 said that they were not confident in their capacity to address patients’ social needs.44 Primary care physicians are being asked to do more with less. Burnout, particularly among primary care physicians, is at an all time high.45

Because MLPs offer assistance to both patients and providers in identifying and addressing unmet social and legal needs that serve to negatively affect health, they support physicians’ knowledge and confidence in addressing social and legal needs. A study in Georgia showed that having the resources of a legal expert on site improves provider satisfaction.46 Studies have also found that MLP education and training for residents improves knowledge of resources and confidence in addressing the SDH.47

Institutions

One of the goals of MLPs is to transform health care delivery to more effectively address the SDH. MLPs have played a crucial role in promoting screening for social and legal needs as well as developing tools for clinicians to use to advocate for their patients, such as form letters in the EMR to improve compliance with laws such as housing codes.48 Some MLPs are leading efforts to promote the use of health informatics to support interprofessional practice and data collection on social determinants.49

In addition, MLPs can render a significant return on investment for health care institutions. For example, one study found that an MLP targeting the needs of cancer patients generated nearly $1 million by resolving previously denied benefit claims.50 Another study of a rural MLP in Illinois demonstrated a 319% return on the original investment of $116 250 over a 3-year period.51

Opportunities for MLP in Primary Care

To date, funding for MLPs has derived from a variety of sources: federal legal aid funding (which has sustained significant cuts in recent years), law school support, law firms, legal bar foundations, fellowship programs, state governments, direct hospital or health center support, health foundation grants, community benefit dollars, and private philanthropy. Health reform has made it possible to think critically about more sustainable funding sources and supports for the MLP approach, particularly as it has demonstrated its potential for fulfilling the quadruple aim. With more attention to the role of primary care, new opportunities for MLP expansion and sustainability are arising.

Community Health Center Expansion

By expanding funding for Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), the ACA is supporting them to advance innovations in integrated care models for vulnerable patient populations. NCMLP has a cooperative agreement with the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to help health centers cultivate and sustain MLPs. In addition, in 2014, HRSA recently clarified that civil legal aid may be included in the range of “enabling services” that HRSA-funded FQHCs provide to meet the primary care needs of the population and communities they serve. FQHCs can now apply for enabling services funds under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act to support the work of legal partners in their clinics.52 In 2015, 6 community health centers used HRSA Expanded Services supplemental funding to support MLP services.53

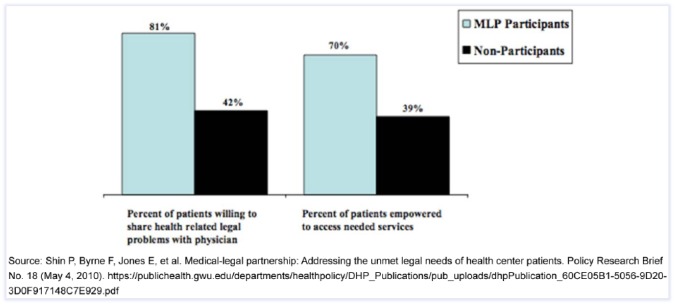

A study of the impact of MLPs in community health centers conducted by George Washington University Department of Health Policy showed that patients in health centers with MLPs were more likely to share legal problems with health care providers and to access needed services than those in FQCHCs without an MLP.17 See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Impact of Medical-Legal Partnerships in Health Centers.

Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) and Community Benefit

Under the ACA, nonprofit hospitals seeking tax exemption must conduct a CHNA every 3 years. The Internal Revenue Service regulations clarify that community health needs include “not only the need to address financial and other barriers to care but also the need to prevent illness, to ensure adequate nutrition, or to address social, behavioral, and environmental factors that influence health in the community.” Hospitals must also develop an implementation strategy to meet the community health needs identified through the CHNA.54,55

Legal partners can be critical contributors to the development of CHNAs by helping assess unmet legal needs as community health needs and in proposing strategies to address them. A key component of a hospital’s implementation strategy is to determine how it will direct resources, typically deployed through its community benefit activities, to address identified community health needs. Some nonprofit hospitals, such as Seattle Children’s Hospital, included its MLP legal partners in the development of its CHNA and then invested in MLP through its community benefits program.56 As nonprofit hospitals begin to shift community benefit funds toward interventions that address the SDH, support for MLPs will be an important consideration.

Team-Based Care and the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH)

One of the models of care being promoted through the ACA is the PCMH as a means to “engage and empower patients, coordinate, track and integrate care, efficiently manage chronic illnesses, reduce unnecessary and duplicative care and, in turn, reduce costs while improving outcomes.”57

The core goals and strategies of PCMH—the whole-patient (and family) approach, focusing on upstream prevention and proactive ways to address patient and family needs, interprofessional collaboration in which each team member can work at the top of his/her license, and connecting clinic to community—are all synergistic with the MLP approach. MLP lawyers train and support primary care providers to recognize legal issues related to the SDH, offer consultation to the health care team, and appropriately refer patients for services. By proactively addressing patients’ legal needs, the goals of MLPs are consistent with the core value of the PCMH—to prevent future illness.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

Similarly, the development of Medicare and Medicaid ACOs offers exciting opportunities for integration of the MLP approach into care models for vulnerable patients. ACOs bring together doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers to coordinate care for a defined group of patients with the goal of delivering coordinated, efficient, high-quality, and cost-effective care.58

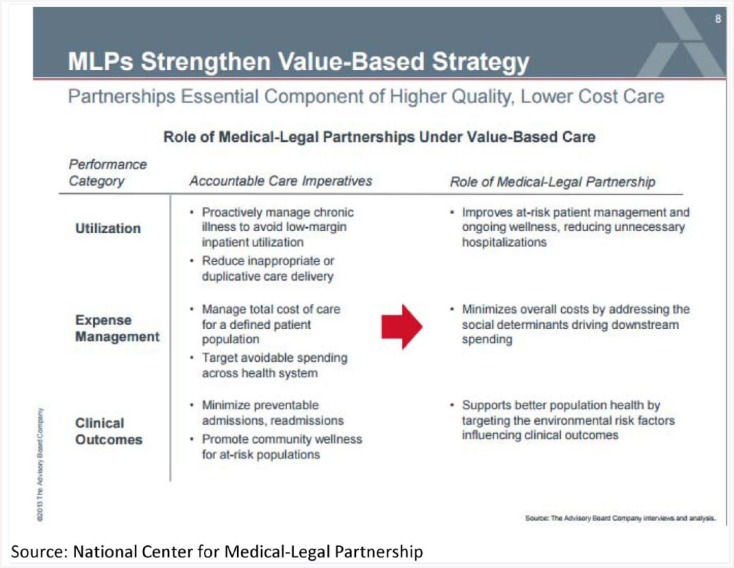

As described earlier, studies are showing the MLP’s potential for return on investment to health care institutions and payers while also improving patient outcomes and experience of care. Some states have begun to develop Medicaid ACOs that focus on improving the health and reducing the costs of patients with chronic illness. Given that the MLP’s explicit focus is on vulnerable low-income patients, those most likely to be Medicaid enrollees, integration of legal expertise and assistance directed at members of Medicaid ACOs may be an effective way to support state efforts to reduce unnecessary health care use while improving health care quality and advancing population health goals. Figure 3 further shows how MLPs strengthen value-based health care strategies such as ACOs.

Figure 3.

MLPs Strengthen Value-Based Strategies.

Abbreviation: MLP, medical-legal partnerships.

Primary Care and Behavioral Health Integration

The ACA promotes behavioral health services by including them in the essential health benefits required of participating plans, establishing parity between the mental and physical health benefits covered by these health plans, and establishing new mechanisms and funding opportunities for integrated care models (such as ACOs and PCMHs). New strategies for implementing behavioral health integration include the following: universal mental health screening, health system navigators, co-location of mental health services, health homes that focus on supporting patients through their behavioral health provider, and system-level integration through payment reforms.59

Not surprisingly, unmet legal needs can inhibit effective behavioral health treatment. For example, a patient experiencing debilitating depression and anxiety may be at risk of eviction and/or job loss. Legal intervention may prevent a downward spiral toward poverty and homelessness while appropriate behavioral health care can be implemented. The move toward integration of behavioral health care into primary care offers a promising avenue to better coordinate care for patients with behavioral health needs. Partnering primary care and behavioral health care providers with attorneys can help provide necessary patient supports, including medical and psychosocial treatments, family participation, and access to community resources. Nationally, there are a growing number of behavioral health–focused MLPs.60,61 Programs that include primary care, behavioral health, and social and legal services for homeless patients offer good examples of full integration.62

Conclusion

MLP is a promising approach to addressing the SDH for vulnerable populations. Integrating lawyers into the health care team to address SDH and to train and consult with health care staff about the unmet legal needs affecting their patients’ health facilitates upstream prevention and policy change. Studies point to the potential for MLPs to improve health, health care delivery, and provider satisfaction while also reducing costs.

The ACA and other health system reforms are offering new opportunities for incorporation of MLP into primary care. Increasingly, MLPs are being included as enabling services at FQHCs and community benefit strategies in nonprofit hospitals, integrated into PCMHs and ACOs, and added into primary care behavioral health innovations. With their focus on reducing health disparities for vulnerable populations, MLPs are an important part of a more comprehensive, patient-centered, preventive, and equitable health care system.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership, National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership. http://medical-legalpartnership.org/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 2. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Mockenhaupt RE. Broadening the focus: the need to address the social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1 S1):S4-S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frieden TR; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC health disparities and inequalities report—United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62(suppl 3):1-187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bradley E, Taylor L. The American Health Care Paradox. New York, NY: Perseus Books; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradley E, Canavan M, Rogan E, et al. Spending on social services, public health, and health care, 2000–09. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016; 35:760-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nuruzzaman N, Broadman M, Kourouma K, Olson D. Making the social determinants of health a routine part of medical care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26:321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains in Electronic Health Records. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Phalen J, Paradis R. How community health workers can reinvent health care delivery in the US. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/01/16/how-community-health-workers-can-reinvent-health-care-delivery-in-the-us/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 11. Taylor LA, Tan AX, Coyle CE, et al. Leveraging the social determinants of health: what works. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accountable health communities model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/AHCM. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 13. Lawton EM, Sandel M. Investing in legal prevention: connecting access to civil justice and healthcare through medical-legal partnership. J Leg Med. 2014;35:29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. US Census Bureau. Poverty. http://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty.html. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 15. Legal Services Corporation. Documenting the justice gap in America: the current unmet civil legal needs of low-income Americans. http://www.lsc.gov/sites/default/files/LSC/images/justicegap.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 16. Pal N. Cuts threaten civil legal aid: funding shortfalls force more low-income families to face critical legal needs alone. https://www.brennancenter.org/analysis/cuts-threaten-civil-legal-aid. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 17. Tobin-Tyler E. When are laws strictly enforced? Criminal justice, housing quality, and public health. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/11/05/when-are-laws-strictly-enforced-criminal-justice-housing-quality-and-public-health/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 18. Shin P, Byrne FR, Jones E, Teitelbaum J, Repasch L, Rosenbaum S. Medical-legal partnerships: addressing the unmet legal needs of health center patients. Policy Research Brief No. 18 (May 4, 2010). https://publichealth.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/DHP_Publications/pub_uploads/dhpPublication_60CE05B1-5056-9D20-3D0F917148C7E929.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 19. Parmet W. Populations, Public Health and the Law. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership. The MLP response. http://medical-legalpartnership.org/mlp-response/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 21. Tobin-Tyler E. Allies not adversaries: teaching collaboration to the next generation of doctors and lawyers to address social inequality. J Health Care Law Policy. 2008;11:249-294. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benfer E. Educating the next generation of health leaders: medical-legal partnership and interprofessional graduate education. J Leg Med. 2014;35:113-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tobin-Tyler E, Teitelbaum J. Training the 21st century healthcare team: maximizing interprofessional education through medical-legal partnership. Acad Med. 2016;91:761-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Association of American Medical Colleges. Achieving Health Equity: How Academic Medicine Is Addressing the Social Determinants of Health. 2016. https://www.aamc.org/download/460392/data/sdoharticles.pdf

- 25. Cohen E, Fullerton DF, Retkin R, et al. Medical-legal partnership: collaborating with lawyers to identify and address health disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2):S136-S139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paul E, Curran M, Tobin-Tyler E. The medical-legal partnership approach to teaching social determinants of health and structural competency in residency programs. Acad Med. 2017;92:292-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keller D, Jones N, Savageau JA, Cashman SB. Development of a brief questionnaire to identify families in need of legal advocacy to improve child health. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:266-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Center for Medical Legal Partnership. Report: screening for health-harming legal needs. http://medical-legalpartnership.org/resources/screening/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 30. Gottlieb LM, Tirozzi KJ, Manchanda R, et al. Moving electronic medical records upstream: incorporating social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:215-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tobin-Tyler E. Aligning public health, health care, law and policy: medical-legal partnership as a multilevel response to the social determinants of health. J Health Biomed Law. 2012;8:211. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beck AF, Klein MD, Schaffzin JK, Tallent V, Gillam M, Kahn RS. Identifying and treating a substandard housing cluster using a medical-legal partnership. Pediatrics. 2012;130:831-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership. Stories from the field: spanning patients to policy. http://medical-legalpartnership.org/mlp-response/stories/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 34. National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership. Partnerships across the U.S. http://medicallegalpartnership.org/partnerships/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 35. PBS Newshour. Why doctors are prescribing legal aid for patients in need. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/doctors-prescribing-legal-aid-patients-need/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 36. Ryan AM, Kutob RM, Suther E, Hansen M, Sandel M. Pilot study of impact of medical-legal partnership services on patients’ perceived stress and well-being. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:1526-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weintraub D. Pilot study of medical-legal partnership to address social and legal needs of patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O’Sullivan M, Branfield J, Hoskote S, et al. Environmental improvements brought by the legal interventions in the homes of poorly controlled inner-city adult asthmatic patients: a proof-of-concept study. J Asthma. 2012;49:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pettignano R, Caley SB, Bliss LR. Medical-legal partnership: impact on patients with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1482-e1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Atkins D, Heller SM, DeBartolo E, Sandel M. Medical-legal partnership and healthy start: integrating civil legal aid services into public health advocacy. J Leg Med. 2014;35:195-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sege R, Preer G, Morton SJ, et al. Medical-legal strategies to improve infant health care: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136:97-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O’Sullivan MM, Brandfield J, Hoskote SS, et al. Environmental improvements brought by the legal interventions in the homes of poorly controlled inner-city adult asthmatic patients: a proof-of-concept study. J Asthma. 2012;49:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Martin J, Martin A, Schultz C, Sandel M, et al. Embedding civil legal aid services in care for high-utilizing patients using medical-legal partnership. Health Affairs Blog. April 22, 2015. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/04/22/embedding-civil-legal-aid-services-in-care-for-high-utilizing-patients-using-medical-legal-partnership/. Accessed March 13, 2017.

- 44. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Health care’s blind side: the overlooked connection between social needs and health: summary of findings from a survey of America’s physicians. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/surveys_and_polls/2011/rwjf71795. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 45. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pettignano R, Caley SB, McLaren S. The health law partnership: adding a lawyer to the health care team reduces system costs and improves provider satisfaction. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18:E1-E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Klein MD, Kahn RS, Baker RC, Fink EE, Parrish DS, White DC. Training in social determinants of health in primary care: does it change resident behavior? Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:387-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sandel M, Hansen M, Kahn R, et al. Medical-legal partnerships: Transforming primary care by addressing the legal needs of vulnerable populations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1697-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gilbert AL, Downs SM. Medical legal partnership and health informatics impacting child health: interprofessional innovations. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:564-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rodabaugh KJ. Medical-legal partnership as a component of a palliative care model. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:15-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Teufel JA. Rural medical-legal partnership and advocacy: a three-year follow-up study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:705-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership. Resources for health centers. http://medical-legalpartnership.org/healthcenters/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 53. Building Resources to Support Civil Legal Aid Access in HRSA Funded Health Centers. National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership, July 2015. http://medical-legalpartnership.org/building-resources/. Accessed March 13, 2017.

- 54. Byrnes M. Hospitals joining forces on community health needs assessment and implementation. http://www.ehcca.com/presentations/phhosp1/byrnes_bo2.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 55. Rosenbaum S. Tax-exempt status for nonprofit hospitals under the ACA: where are the final treasury/IRS rules? http://healthaffairs.org.revproxy.brown.edu/blog/2014/10/23/tax-exempt-status-for-nonprofit-hospitals-under-the-aca-where-are-the-final-treasuryirs-rules/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 56. Crossley M, Tobin-Tyler E, Herbst J. Tax-exempt hospitals and community health under the Affordable Care Act: identifying and addressing unmet legal needs as social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2016;131:195-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Romney MC. Medical-legal partnerships as a value-add to patient-centered medical homes. http://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1751&context=hpn. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 58. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. What’s an ACO? https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ACO/index.html?redirect=/aco/. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 59. Arsenow J, Rozenman M. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:929-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zelhof J, Fulton S. MFY legal services’ mental health-law partnership: Clearinghouse review. J Poverty Law Policy. 2011;44:535. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wong C, Tsai J. Helping veterans with mental illness overcome civil legal issues: collaboration between a veterans affairs psychosocial rehabilitation center and a nonprofit legal center. Psychol Serv. 2013;10:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tran A. Clinic for the homeless to open in Oakland. http://ww2.kqed.org/stateofhealth/2012/08/08/clinic-for-the-homeless-to-open-in-oakland/. Accessed March 8, 2017.