Abstract

Expression of the 180-kDa canine ribosome receptor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to the accumulation of ER-like membranes. Gene expression patterns in strains expressing various forms of p180, each of which gives rise to unique membrane morphologies, were surveyed by microarray analysis. Several genes whose products regulate phospholipid biosynthesis were determined by Northern blotting to be differentially expressed in all strains that undergo membrane proliferation. Of these, the INO2 gene product was found to be essential for formation of p180-inducible membranes. Expression of p180 in ino2Δ cells failed to give rise to the p180-induced membrane proliferation seen in wild-type cells, whereas p180 expression in ino4Δ cells gave rise to membranes indistinguishable from wild type. Thus, Ino2p is required for the formation of p180-induced membranes and, in this case, appears to be functional in the absence of its putative binding partner, Ino4p.

INTRODUCTION

Biological membranes that enclose the organelles of eukaryotic organisms are composed of a lipid bilayer and integral proteins that reside within it. Although the structure and function of various cellular membranes have been extensively characterized, how they assemble in response to certain stimuli is poorly understood. The endoplasmic recticulum (ER), a prominent feature of actively secreting cells, is the site of translocation and initial processing of secretory proteins in eukaryotes. Developmentally regulated ER biogenesis occurs in cells of specialized mammalian tissues, such as pancreas and liver (Dallner et al., 1966a, 1966b) as well as during the antigen-induced maturation of B lymphocytes into plasma cells (Chen-Kiang, 1995).

Simplified systems for studying ER biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been recently described. Membrane proliferation has been observed in cells that express high levels of certain integral ER membrane proteins such as the yeast HMG-CoA reductase isozymes, Hmg1p and Hmg2p (Wright et al., 1988; Koning et al., 1996), cytochrome P450 (Schunck et al., 1991), and various domains of the mammalian ribosome receptor, p180 (Wanker et al., 1995; Becker et al., 1999). ER-like membrane morphologies arise from the overexpression of the peroxisomal integral membrane protein, Pex15p (Elgersma et al., 1997). In addition, a yeast strain harboring a temperature-sensitive allele of the Golgi membrane protein, Yip1p, has also been shown to accumulate of ER-like membranes (Yang et al., 1998).

Several obvious questions arise. Is there a common mechanism that leads to the proliferation of intracellular membranes in these situations? If so, which gene products participate? How is the process regulated, and what are the regulatory elements? It is the purpose of the work described here to begin to address these issues.

The lipid component of the yeast ER membrane consists largely of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylinositol (Jakovcic et al., 1971). The rate-limiting step in inositol phospholipid biosynthesis is carried out by the INO1 gene product. The transcription of INO1 and other phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes have been well characterized in yeast. Many of these genes are regulated by the intracellular concentration of free inositol and choline (see Greenberg and Lopes, 1996; Henry and Patton-Vogt, 1998 for review). When inositol and choline levels are low, a transcription factor complex composed of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins, Ino2p and Ino4p, activates the expression of many genes encoding phospholipid, fatty acid, and sterol biosynthetic enzymes. Ino2p and Ino4p form a functional heterodimer that binds to a conserved upstream activating sequence (UASINO) residing in the promoters of these genes (Lopes et al., 1991; Ambroziak and Henry, 1994; Nikoloff and Henry, 1994; Koipally et al., 1996). Ino2p has been shown to contain transactivation domains (Schwank et al., 1995), whereas Ino4p is required for the binding of the complex to UASINO.

Genes involved in lipid biosynthesis are also negatively regulated by a subset of genes. Of these, the OPI1 gene product represses the transcription of INO1 and other phospholipid biosynthetic genes in response to inositol and choline (Lai and McGraw, 1994; Ashburner and Lopes, 1995a, 1995b). However, there is evidence that Opi1p may not be responsible for the transmission of the signal that leads to repression of INO1 in response to phospholipid precursors (Graves and Henry, 2000). Overproduction of Opi1p was shown to render wild-type yeast auxotrophic for inositol, supporting the notion that it is a negative regulator of phospholipid biosynthesis (Wagner et al., 1999).

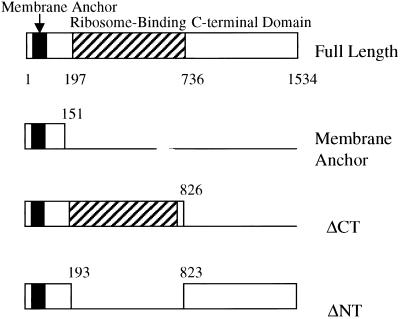

Genes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis might be differentially expressed in systems where ER biogenesis is accelerated. To identify genes whose levels of expression change during stimulated membrane production, microarray analysis was performed using mRNA isolated from cells expressing the canine ribosome receptor (p180) or specific regions of it known to produce membrane proliferation in yeast. The canine ribosome receptor is an integral membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) consisting of three distinct regions based on its amino acid sequence (Wanker et al., 1995). Briefly, full-length p180 (FL) consists of an amino terminal membrane-anchoring domain, a basic region consisting of 54 tandem decapeptide repeats involved in ribosome binding and a C-terminal predicted coiled-coil domain of unknown function (Langley et al., 1998). Expression of FL results in the proliferation of rough membranes evenly spaced throughout the cytoplasm. Expression of the ΔCT construct, which lacks the C-terminal domain, gives rise to closely packed rough membranes. Expression of the ΔNT construct, lacking the ribosome-binding domain, leads to the proliferation of smooth, evenly spaced membranes 80–100 nm apart. When the membrane-anchoring (MA) region alone was expressed, proliferation of “karmellae” or stacks of closely packed, smooth perinuclear membranes was observed.

Pilot studies using microarray analysis suggested that several genes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis are differentially expressed in all strains where membrane proliferation was induced. Among them were key transcription factors involved in the regulation of phospholipid metabolism. Of these, INO2 mRNA was upregulated, and the transcripts of INO4 and OPI1 were downregulated. The results presented here show that Ino2p is essential for the process of stimulated ER biogenesis in yeast, irrespective of the membrane protein expressed. Actions that ameliorate the viability of strains deleted for Ino2p, such as added inositol and choline, do not restore the ability to proliferate membranes. Moreover, other putative regulatory proteins, such as Ino4p, do not appear to be essential to the process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Expression Plasmids

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study were as follows: SEY6210 (MATα leu2-3112 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9; Wilsbach and Payne, 1993), J51-5c (MATα ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ901 ptl1-1; Toyn et al., 1988), W303 (MATaura3-1 leu2-3112 trp1-1 ade2-1 his3-11,15 can1-100), JAG1 (MATa his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 opi1Δ::LEU2), JAG2 (MATa his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 ino2Δ::TRP1), JAG4 (MATahis3 leu2 trp1 ura3 ino4Δ::LEU2). JAG1, 2, and 4 were obtained from Susan Henry (Carnegie Mellon University) and constructed from the parental strain W303 (Graves and Henry, 2000).

p180 plasmids used for microarray analysis and Northern blotting were constructed in the pYEX-BX plasmid containing the CUP1 promoter (Amrad Biotech, Victoria, Australia). Cloning and plasmid transformation were carried out as described by Becker et al. (1999), and the constructs used are diagrammed in the Appendix. The ΔCT-GFP construct was created by amplifying an EGFP fragment (Patterson et al., 1997) using AccIII- and SalI-modified primers: (5′AAGGAGTCCGGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTT 3′, 5′GATCTCGGGCCCGTCGACCTACAATTCGTCGTG 3′). The GFP fragment was inserted into the YEX–BX vector containing full-length p180 cut at AccIII and SalI sites, creating a C-terminal truncation of p180. Expression of copper-inducible p180 plasmids was carried out in 2% dextrose (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), 0.17% Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate (Fisher Scientific), and 5% ammonium sulfate (Fisher Scientific) plus 0.5 mM copper sulfate. The concentration of inositol from yeast nitrogen base is 2 mg/l or 11 μM. Amino acids were supplemented (without uracil and leucine) as described by Guthrie and Fink (1991). After 5 h growth in copper, yeast cells were harvested and used for further study. Plasmids containing HMG1 and HMG2-GFP fusions were obtained from Robin Wright (University of Washington), transformed into W303 and JAG2 strains, and expressed under conditions described by Koning et al. (1996).

RNA Isolation and Northern Blotting

RNA isolation was performed by the method of Hollingsworth et al. (1990). Total RNA (5 μg) was separated on a 1.2% formamide-containing agarose gel (Maniatis et al., 1982) and transferred to MagnaGraph nylon membrane (Osmonics, Westborough, MA). Probes were generated from PCR using primer pairs listed below and using yeast genomic DNA as a template: PGK1, 5′-AACGTCCCATTGGACGGTAA-3′ and 5′-TCTTGTCAGCAACCTTGGCA-3′; INO2, 5′-ATGCAACAAGCAACTGGGAA-3′ and 5′-TTCATGGAAGCGTTGGAAGA-3′; INO4, 5′-TGACGAACGATATTAAGG-AGATAC-3′ and 5′-TCACTGACCACTCTGTCCATCA-3′; OPI1, 5′-TGTCTGAAAATCAACGTTTAGGA-3′ and 5′ CAACAAGGTCCTGTAAACACGA-3′. Quantitative Northern blotting was performed using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Microarray Analysis

p180-plasmids in strain SEY6210 were induced for 5 h, and RNA was harvested as described above. For microarrays, cDNA synthesis, labeling, hybridization, and scanning were performed as described by Lipshutz et al. (1999) and Lockhart and Winzeler (2000). Genes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis were categorized according to lists provided by the Yeast Proteome Database (Costanzo et al., 2000, 2001).

DiOC6 and Propidium Iodide Staining

Yeast cells were grown under desired conditions in liquid culture to mid log phase. For DiOC6 (3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanineiodide) staining, ∼1 OD600 of cells were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml TE buffer. DiOC6 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was resuspended to 1 mg/ml in ethanol. One microliter DiOC6 stock solution was added to the yeast cell suspension. Cells were analyzed immediately. Propidium iodide (PrI) was purchased from Molecular Probes. Staining was carried out as described by Deere et al. (1998).

Flow Cytometry

Approximately 30,000 yeast cells were acquired per sample using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). The detection threshold was set in the FSC channel just below the lowest detectable level of the yeast suspension with the lowest intensity. GFP-expressing and DiOC6-stained cells were detected in channel FL-1. PrI-stained cells were detected in channel FL-2. Analysis was carried out using CELLQuest software (Becton-Dickinson).

Fluorescence Microscopy

DiOC6-stained and GFP-expressing cells were visualized with a Nikon DIOPHOT 200 (Garden City, NY) inverted microscope with 60× and 100× objective lenses and fluorescent filters with 488-nm excitation wavelength. Images were collected using Inovision Isee software (Raleigh, NC).

Electron Microscopy

Yeast cells were fixed by immersion in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) by addition of double-strength fixative to cells in suspension. The cells were pelleted and left in fixative for 24 h. They were embedded in Spurr low viscosity resin (EMS, Fort Washington, PA) using a modification of a previously published method (Kaiser and Schekman, 1990).

The cells were transferred to 15-ml plastic falcon tubes in 10 ml of water. All exposures to processing solutions were performed in at least a 10 ml volume. Cells were washed in three changes of water and then resuspended in 10 ml of 1% aqueous osmium tetroxide. The closed tubes were exposed to microwaves for 40 s and then left for 3 h. The microwave processor used (Ted Pella Inc, Redland, CA) was calibrated and operated as previously described (Giberson and Demaree, 1999) and equipped with recycling water load, in the form of a “cold spot,” as supplied by the manufacturer. All microwave exposures were performed using the processor set to deliver full power. Cells were washed again in water and resuspended in 70% methanol saturated with uranyl acetate. The cells were exposed to microwaves for 40 s and then left overnight at 4°C.

The cells were washed with five changes of 70% methanol and dehydrated through graded acetone series, starting at 70%. Each dehydration step consisted of a 40-s exposure to microwaves with 10 min on a stirring wheel.

Infiltration in resin consisted of a 15-min exposure to microwaves followed by an overnight incubation in a 1:1 mixture of Spurr resin and acetone. The yeast were resuspended in the resin/acetone mixture and left on a mixing wheel. The following day, the yeast were resuspended in 10 ml of fresh resin, exposed to microwaves for 15 min, and left mixing for 2 h. The cells were embedded in fresh resin that was polymerized at 60°C.

Thin sections were mounted onto coated metal specimen grids and photographed in a CM120 BioTwin TEM (FEI-Philips, Hillboro, OR) operating at 80 kV. Negative film, developed in liquid developer, was digitalized using a flat-bed scanner and the images were manipulated to adjust contrast and brightness with Adobe PhotoShop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

35S Labeling and Immunoprecipitation of Carboxypeptidase Y

Yeast cultures were grown to stationary phase in synthetic medium, with the appropriate amino acid supplements, and with or without inositol for ino2Δ strains. Cells were diluted to 0.2 OD/ml and grown to OD600 = 1–2, harvested by centrifugation, and washed twice with synthetic complete media, pH 5.7. Cells were resuspended at 2 OD600/ml in synthetic complete media plus BSA at 1 mg/ml and α2-macroglobulin at 10 mg/ml. After preincubation for 15 min at the desired temperature, 50 μCi of 35S-cysteine/methionine was added per 1 OD600, and cells were incubated for 10 min shaking at 37°C (for ptl1 and wt strains) of 30°C (for ino2Δ strains). Cells were chased by adding 1/10 vol 3 mg/ml methionine and 3 mg/ml cysteine dissolved in 2% yeast extract. Aliquots (250 μl) of cells were removed at the desired time points to tubes on ice containing 2.5 μl 1 M NaF and 2.5 μl NaN3.

Cells were pelleted and supernatant was removed. The cells were spheroplasted with 10 μg/ml oxyliticase in 100 μl spheroplast buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1.4 M sorbitol, and 5 mM MgCl2) plus 4 mM β-ME and 10 mM NaN3. Cells were incubated at 30°C for 30 min and pelleted for 6 min at 3000 rpm, and the supernatant was removed. The cells were resuspended in 100 μl 2% SDS and incubated at 100°C for 3 min. PT (1× PBS, 1% TX-100), 0.9 ml, was added to cell lysate. The lysates were precleared with 50 μl 10% Staphylococcus aureus cells on ice for 15 min and then pelleted 15 min at full-speed in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant was removed to a new tube with carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) antisera (Greg Payne, UCLA) and Protein A sepharose was added (25 μl of 20% solution). The tubes were rotated overnight at 4°C. Samples were pelleted and washed twice with 0.5 ml of each: PTS (1× PBS, 1% TX-100, 0.1% SDS), urea wash (2 M urea, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% TX-100, 2 M NaCl), and Tris/NaCl wash (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10 mM NaCl). After washing, pellets were resuspended in 25 μl 1× Laemmli sample buffer, heated for 3 min at 100°C, and resolved on an 8% SDS-PAGE.

RESULTS

Quantification of p180-induced Membrane Proliferation: Increased Appearance of Lipid Bilayers

The expression of different regions of canine p180 in yeast gives rise to rough or smooth ER-like membranes as previously documented primarily by electron microscopy as well as biochemically through measurement of increase in membrane lipid on a per cell basis (Wanker et al., 1995). To demonstrate that the membranes observed resulted from the synthesis of new membranes and not from the incorporation of proteins into preexisting membranes, total membrane quantification was carried out. Here, the lipophilic fluorescent dye, DiOC6, was used to quantify increases in intracellular membrane content in living cells upon expression of the ΔCT construct of p180 in yeast. DiOC6 has been used previously to assess and quantify membrane proliferations that arise from overexpression of the HMG-CoA reductase isoforms, Hmg1p and Hmg2p (Koning et al., 1996; Parrish et al., 1995).

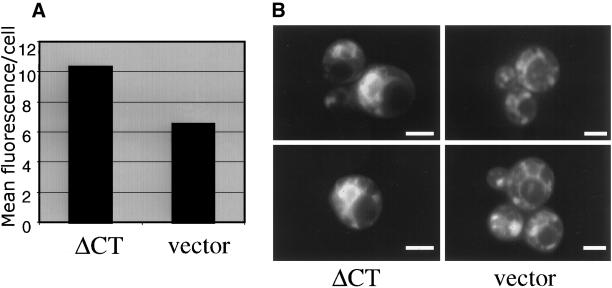

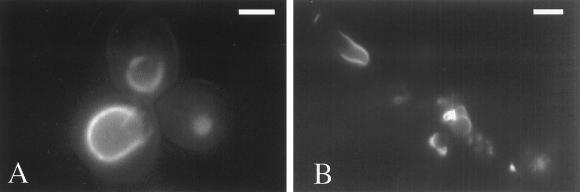

ΔCT and vector-expressing cells were incubated with DiOC6, and fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry. Calculations based on the mean fluorescence value per cell revealed that ΔCT-expressing cells absorb ∼1.6 times as much of the lipophilic dye compared with vector-expressing cells (Figure 1A). However, it should be noted that this represents a minimum value because the absorbance of DiOC6 is not limited to ER and nuclear membranes, and thus the quantification of membranes by DiOC6 staining is more accurately a representation of total cellular membranes (e.g., mitochondria, Golgi, and vacuole). To confirm that the increase in DiOC6 absorption resulted from an increase in ER membrane content, ΔCT- and vector-expressing cells stained with DiOC6 were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 1B). Cells expressing ΔCT were visualized as having bright asymmetric rings emanating from the nucleus. In contrast, control cells showed only dim perinuclear and other membrane staining. These observations corroborate the morphological changes previously seen in electron micrographs and establish increased lipid content due to p180-induced membrane proliferation.

Figure 1.

Membrane proliferation quantified by the incorporation of the lipophilic dye, DiOC6. ΔCT-YEX– and YEX-BX (vector)–expressing cells were induced for 5 h with 0.5 mM CuSO4. Cells were harvested and resuspended to 1 OD600/ml in TE buffer. Cells were treated with DiOC6 to a final concentration of 1.0 μg/ml. Cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis and the mean fluorescence value per cell was plotted in A. DiOC6-stained cells viewed by fluorescence microscopy (B). Bar, 1.0 μm.

Genes Involved in Lipid Metabolism are Differentially Expressed in p180-Expressing Cells

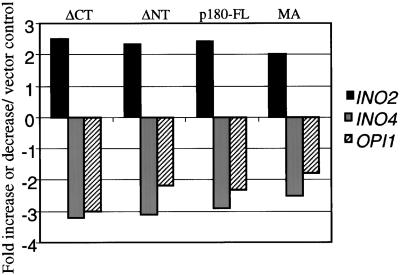

To determine if induction of specific genes is associated with p180-stimulated membrane proliferation, microarray analysis was performed. RNA isolated from strains expressing four different forms of p180 (ΔCT, ΔNT, FL, and MA) as well as a vector-transformed control was used to prepare probes. A pilot study revealed that several genes involved in lipid biosynthesis may be differentially expressed in strains expressing all forms of p180 compared with the vector transformed control. This single set of microarray data, collected under the conditions described, enabled the selection of genes of interest chosen for further investigation. In each of these cases, accurate changes in mRNA levels were established by quantitative Northern analysis. Interestingly, INO2 mRNA, which encodes a bHLH transcription factor required for the derepression of phospholipid biosynthetic genes was found by array analysis and confirmed by Northern blotting to be upregulated in all p180-expressing strains (Figure 2). In contrast, OPI1 mRNA, which encodes a transcriptional repressor of phospholipid biosynthesis, was downregulated (Figure 2). Microarray analysis also revealed INO4 mRNA to be downregulated (Figure 2). This was unexpected because Ino2p and Ino4p have been shown to form a functional heterodimer that activates transcription of phospholipid biosynthetic genes upon inositol starvation (Lopes and Henry, 1991). In addition, INO4 has not been shown previously to be regulated at the transcriptional level (Ashburner and Lopes, 1995b; Robinson and Lopes, 2000a). Other genes involved in lipid biosynthesis found to be upregulated by Northern blotting, included those encoding inositol-1-phosphate (INO1), glycerol-3-kinase (GUT1), and a gene required for inositol prototrophy (SCS3; our unpublished results).

Figure 2.

Northern blot quantification of INO2, INO4, and OPI1 upon p180 induction. Yeast strains were induced to express various forms of p180 (ΔCT, ΔNT, p180-FL, MA) and a vector control for 5 h. RNA was harvested, and 5 μg RNA was loaded per lane. Blots were probed with radiolabeled fragments of INO2, INO4, OPI1, and PGK1. Quantified band intensities were normalized to PGK1 for loading control. Values obtained for RNA from p180-expressing strains were compared with vector control strains. Black bars, INO2; gray bars, INO4; striped bars OPI1.

To determine if the differentially expressed genes profiled above play any role in the formation of p180-induced membranes, genetic and biochemical analyses were carried out.

Regulators of Phospholipid Biosynthesis in Yeast: The Roles of INO2, INO4, and OPI1 in the Formation of Inducible Membranes

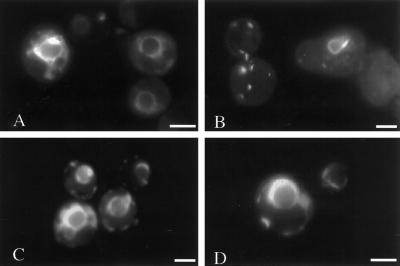

The observation that transcript levels of positive and negative regulators of lipid biosynthesis were differentially expressed in p180-expressing strains suggests that regulation of INO2, INO4, and OPI1 may be important for the formation of p180-induced membranes. A ΔCT-GFP fusion construct was expressed in wild-type, ino2Δ, ino4Δ, and opi1Δ backgrounds (Figure 3) to observe if strains lacking these genes are affected in membrane proliferation.

Figure 3.

Cells deleted for INO2 fail to undergo p180-induced membrane proliferation. Cells carrying the ΔCT-GFP-YEX plasmid were induced for 5 h with 0.5 mM CuSO4. Cells were resuspended to 1 OD600/ml in TE buffer. Seven microliters of cell suspension was placed on a glass slide and viewed by fluorescence microscopy. Wild-type strain W303 expressing ΔCT-GFP exhibited perinuclear fluorescent patterns (A). Cells deleted for INO2 (JAG2) exhibited aberrant membrane structures (B). Cells deleted for INO4 (JAG4) gave rise to membranes similar to wild type (C). Cells deleted for OPI1 contained bright, dense perinuclear structures (D). Bar, 1.0 μm.

INO2, but not INO4, Is Required for p180-induced Membrane Proliferation

In wild-type cells, both the expression of ΔCT-GFP and DiOC6-stained ΔCT-expressing cells gave rise similar proliferated membrane morphologies (cf. Figures 1A and 3A). However, ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT-GFP failed to accumulate p180-induced membranes (Figure 3B). Instead, these cells included shrunken perinuclear structures and punctate fluorescent spots. ΔCT-expressing cells deleted for INO4, which encodes the putative binding partner for Ino2p, were indistinguishable from wild-type cells (cf. Figure 3, C and A). This observation is intriguing because evidence to date has linked both Ino2p and Ino4p to derepression of phospholipid biosynthetic genes (Lopes and Henry, 1991; Ashburner and Lopes, 1995b). Both proteins are required for the formation of a complex that binds to the UASINO of INO1 and other phospholipid biosynthetic genes (Ambroziak and Henry, 1994; Schwank et al., 1995).

p180-induced Membrane Proliferation Appears Enhanced in opi1Δ Cells

To determine the role of Opi1p, a negative regulator of phospholipid biosynthesis, in p180-induced membrane biogenesis, we expressed ΔCT-GFP in opi1Δ cells. It is unclear how Opi1p represses phospholipid biosynthesis, but it has been shown to repress INO1 transcription in the presence of inositol (Lai and McGraw, 1994; Ashburner and Lopes, 1995a, 1995b; Henry and Patton-Vogt, 1998). This result is consistent with the downregulation of OPI1 mRNA in p180-expressing cells. Figure 3D shows that opi1Δ cells expressing ΔCT-GFP accumulate thick, bright perinuclear rings. Because it is difficult to quantify the degree of membrane accumulation by fluorescence microscopy, we subjected opi1Δ and the above-mentioned strains expressing ΔCT-GFP to flow cytometry analysis.

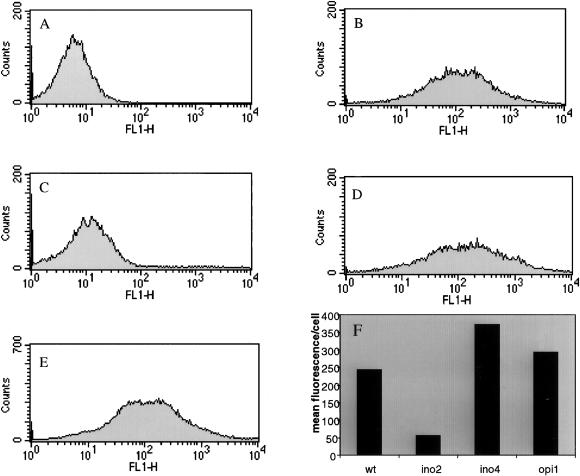

Fluorescence-activated flow cytometry is an efficient and rapid method of gauging the amount of fluorescence per cell for a population expressing a fluorescent marker. Here, flow cytometry was used as a measure of membrane accumulation in cells expressing ΔCT fused to GFP. This proved to be a valid measure of membrane accumulation as the mean fluorescence value per cell of ΔCT-GFP–expressing cells was approximately twice that of MA-GFP–expressing cells (unpublished observations). This difference mirrors the relative amounts of membranes visualized in ΔCT- versus MA-expressing cells by electron microscopy (Becker et al., 1999).

Figure 4 shows the fluorescence profiles of wild-type and various knockout strains expressing ΔCT-GFP. This method is used to quantify the fluorescence levels of ΔCT-GFP–expressing strains on a per-cell basis. The autofluorescence of wild-type yeast cells is profiled in Figure 4A. Expression of ΔCT-GFP caused wild-type cells to accumulate membranes and a consequential shift in the fluorescence profile to the right indicating an increase in fluorescence (Figure 4B). Consistent with fluorescence microscopy, the flow cytometry profile of ino2Δ cells shifted back to the left, indicating a deficiency in membrane proliferation (Figure 4C). The profiles of ino4Δ and opi1Δ strains expressing ΔCT-GFP resembled that of the wild-type population (Figure 4, D and E). The mean fluorescence level per cell for the above profiles was plotted in Figure 4F. Cells harboring a deletion in INO2 emitted approximately fivefold less fluorescence than wild-type cells expressing ΔCT-GFP. We conclude that ino2Δ cells are deficient in their ability to proliferate p180-induced membranes. To rule out the possibility that p180 expression was affected in an ino2Δ background, Northern blot analysis was performed on ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT-GFP. The results confirmed normal levels of p180 expression (unpublished observations). In contrast to the ino2Δ strain, the mean fluorescence values of ino4Δ and opi1Δ strains expressing ΔCT-GFP were 1.5- and 1.2-fold higher, respectively, than wild type. An interesting pattern seems to emerge, at least in the case of lipid biosynthetic genes. Strains harboring deletions in genes whose transcript levels increase during induced membrane proliferation (INO2) failed to respond to p180 induction by proliferating membranes, whereas cells deleted for genes whose transcript levels fall (INO4 and OPI1), appeared to produce increased levels of membranes. Visualization of membrane accumulation along with fluorescence quantification of ΔCT-GFP indicates that INO2 is essential for the formation of p180-inducible membranes in yeast, whereas INO4 is dispensable and that membrane accumulation is even enhanced in its absence.

Figure 4.

Quantification of membrane biogenesis: ino2Δ cells fail to accumulate membranes. Cells expressing ΔCT-GFP or vector were induced with 0.5 mM CuSO4 for 5 h. Cells were resuspended to 1 OD600/ml in TE buffer. Approximately 30,000 cells were acquired in a FACScan flow cytometer. The auto-fluorescence of yeast cells is documented in A. (B–D) Different cell populations expressing ΔCT-GFP: wild type (B), ino2Δ (C), ino4Δ (D), opi1Δ (E). The histogram in F compares the mean fluorescence value per cell for B–D.

ino2Δ Cells Are Compromised in the Proliferation of Karmellae

To establish that INO2 is required for the formation of membranes other than those that arise from p180 expression, GFP fusions of the HMG-CoA reductase isoforms, HMG1 and HMG2, were expressed in ino2Δ cells. Increased production of Hmg1p gives rise to whorls of karmellae, or layers of smooth ER membranes that are contiguous with the nuclear membrane (Figure 5A), whereas elevated levels of Hmg2p cause the formation of short stacks of karmellae, with characteristics similar to those of peripheral ER (Koning et al., 1996). Consistent with what was observed in ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT-GFP, HMG1-GFP expression in this strain gave rise to similar aberrant membrane morphologies (Figure 5). Similar results were observed for ino2Δ cells expressing HMG2-GFP (unpublished results). As with p180-expressing cells, INO4 was not required for the proliferation of karmellae. Cells deleted for INO4 expressing HMG1 or HMG2 fused to GFP gave rise to karmellae indistinguishable from the karmellae of wild-type cells expressing these constructs (unpublished results). Based on these results, INO2 appears to be essential for the formation of karmellae.

Figure 5.

Cells deleted for INO2 are compromised in the proliferation of karmellae. Hmg1-GFP was expressed in wild-type and ino2Δ cells under the control of the galactose promoter. Wild-type cells contained whorls of perinuclear membranes or karmellae (A). Cells deleted for INO2 exhibited aberrant punctate membrane structures and elongated perinuclear morphology (B). Bar, 1.0 μm.

Inositol and Choline Do Not Restore Membrane Proliferation in ino2Δ Cells

INO2 and INO4 were identified by complementation as suppressors of inositol auxotrophy (Culbertson and Henry, 1975; Donahue and Henry, 1981). The fact that INO2 mutants are defective in inositol and choline phospholipid biosynthesis raised the possibility that the membrane proliferation defect in ino2Δ cells is due to the absence of inositol and choline for phospholipid biosynthesis. To address this issue, ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT-GFP were grown in conditions of low (10 μM inositol, no choline) or high (75 μM inositol, 1 mM choline) phospholipid precursors. High concentrations of inositol and choline allow ino2Δ cells to achieve growth levels comparable to wild type (Ashburner and Lopes, 1995b).

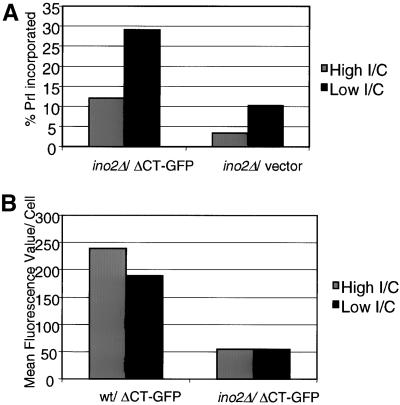

Here, viability of ino2Δ cells under conditions of high or low inositol and choline was ascertained by the incorporation of PrI. PrI can be used to assess yeast cell viability and membrane integrity because it will stain DNA of cells with porous membranes but not intact cells (Deere et al., 1998). Figure 6A shows that the incorporation of PrI into ino2Δ cells was greatly reduced in cells grown in high inositol and choline. Approximately 30% of ΔCT-GFP–expressing ino2Δ cells grown in low inositol were PrI-positive, indicating that this population of cells was dead or had compromised membrane integrity. The fitness of this strain was improved during growth in high inositol and choline, reducing PrI-positive cells to ∼10% of the population. The viability of vector-expressing ino2Δ cells also improved when grown in media containing high inositol and choline.

Figure 6.

Addition of inositol and choline restores viability to ino2Δ cells. (A) PrI incorporation was assessed in ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT or an empty vector. Cells were grown under conditions of low or high concentrations of inositol and choline. Cells were harvested, and PrI was added to a final concentration of 3 μg/1 OD600. PrI-stained cells were acquired by a FACScan flow cytometer, and the percentage of PrI-stained cells was calculated. (B) Fluorescence quantification by flow cytometry of wild-type and ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT-GFP. Gray bars, high I/C (75 μM inositol, 1 mM choline); black bars, low I/C (10 μM inositol, no choline).

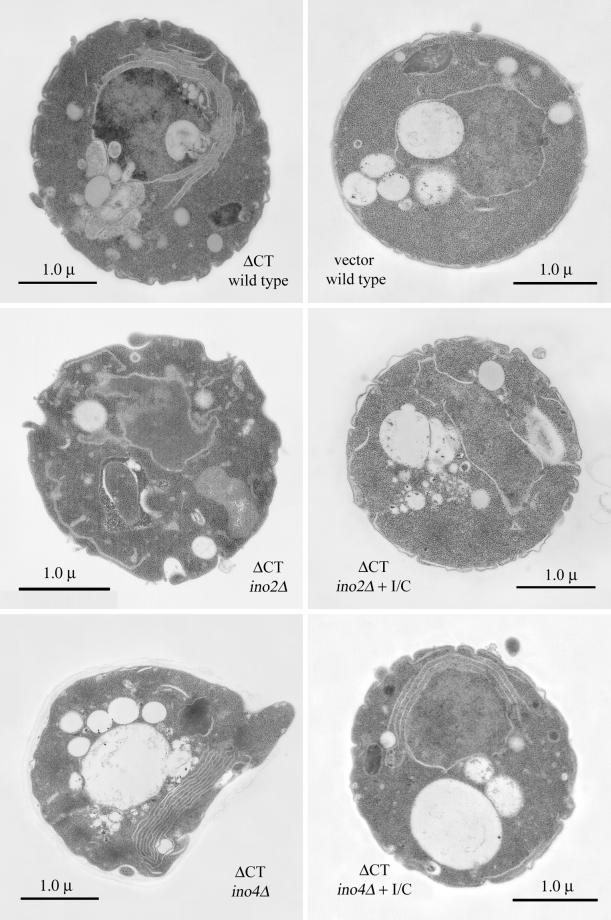

Although addition of inositol and choline restored the viability of ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT-GFP, it failed to rescue the ability of these cells to proliferate membranes. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that these cells appeared nearly identical to cells grown in low inositol (unpublished results; see Figure 3B), and flow cytometry quantification showed no increase in fluorescence of ino2Δ cells supplemented with inositol and choline (Figure 6B). Electron microscopy demonstrated that, although the aberrant morphology of ino2Δ cells was improved when supplemented with inositol and choline, the ability to proliferate membranes was not restored (Figure 7). Cells deleted for INO4 were capable of undergoing membrane proliferation during growth in low or high concentrations of inositol, although they exhibited abnormal morphology when grown without inositol and choline (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Addition of inositol and choline to ino2Δ cells expressing ΔCT does not restore membrane proliferation. Electron micrographs depict membrane morphologies of wild-type cells expressing ΔCT or vector (top panels). ΔCT-expressing cells contain perinuclear arrays of rough membranes. Cells deleted for INO2 were not capable of membrane proliferation, and addition of inositol and choline failed to restore the ability to proliferate membranes (middle panels). Cells deleted for INO4 expressing ΔCT were able to undergo membrane proliferation in the absence of inositol and choline (bottom panels). I/C, 75 μM inositol, 1 mM choline.

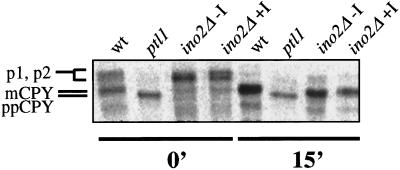

Protein Translocation Is Not Affected in ino2Δ Cells: A Functional Assay for Membrane Integrity

Owing to the pivotal role played by Ino2p in phospholipid biosynthesis, the question arises as to the integrity of cellular membranes in Δino2 cells. Strains deleted for INO2 display a pleiotropic phenotype characterized by defects in nuclear segregation, bud formation and sporulation as well as an oversized morphology (Hammond et al., 1993). This observation raised the possibility that deletion of INO2 may cause a generalized membrane defect that prevents insertion of p180 and other ER membrane proteins into the ER, resulting in an inability of the cells to undergo membrane proliferation. To address the issue of ER membrane integrity in ino2Δ cells, a translocation assay was performed after the maturation of the endogenous yeast glycoprotein, CPY. Wild-type and ino2Δ cells were pulse-labeled, and CPY was immunoprecipitated from cells grown in the presence or absence of inositol. The ptl1 strain described by Toyn et al. (1988) was used as a control for defective CPY translocation. PTL1 is allelic to the SEC63 gene of S. cerevisiae, which encodes an integral membrane protein that is required for the translocation of secretory proteins into the ER (Rothblatt et al., 1989). As shown in Figure 8, CPY was initially observed largely as its glycosylated intermediate forms (p1, p2) for both wild-type and ino2Δ strains in the absence or presence of inositol. As expected, CPY was not translocated into the ER in the ptl1 mutant and remained unmodified as prepro-CPY. After 15 min, the majority of p1 and p2 CPY was chased to its mature form in wild-type cells. Similarly, CPY immunoprecipitated from ino2Δ cells grown in the absence or presence of inositol appeared to be nearly completely processed to mature CPY after 15 min, whereas ptl1 cells exhibited primarily unprocessed prepro-CPY. These data indicate that the ER membrane in ino2Δ cells is intact and functional for protein translocation, suggesting that the requirement for Ino2p in membrane proliferation is not due to compromised membrane integrity.

Figure 8.

Translocation of CPY is normal in ino2Δ cells. A pulse-chase experiment of CPY shows the maturation of CPY in ino2Δ cells is similar to wild type. The mutant strain J51-5c (Toyn et al., 1988), harboring a temperature-sensitive allele of ptl1, was used as a control for defective translocation. Cells were preincubated for 15 min at 37°C (wild type and ptl1) or 30°C (ino2Δ grown in the presence or absence of 75 μM inositol). Cells were pulse-labeled with 35S-methionine/cysteine for 10 min, chased with cold methionine/cysteine, and collected at the desired time points. Preparation of cell extracts and CPY immunoprecipitation was performed as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. ppCPY: prepro-CPY; p1, p2: Golgi glycosylated CPY intermediates; mCPY: mature CPY. +I: 75 μM inositol.

DISCUSSION

The work presented here defines an essential role for Ino2p, a transcriptional activator of phospholipid biosynthesis, in the formation of inducible membranes in S. cerevisiae. Yeast cells expressing p180 accumulated ER membranes as visualized and quantified by incorporation of the lipophilic dye, DiOC6. Microarray analysis of strains expressing various forms of canine p180 revealed the differential expression of several transcripts whose products function in lipid biosynthetic pathways. Among the genes identified in this screen were those encoding the positive transcriptional regulators Ino2p and Ino4p as well as a negative regulator of phospholipid biosynthesis, Opi1p. Membrane accumulation was diminished in an ino2Δ strain expressing the ΔCT form of p180 compared with wild type. Strains deleted for INO4 and OPI1 were not compromised and appeared enhanced in their ability to proliferate membranes. Addition of inositol and choline to ino2Δ cells rescued viability but not the ability to proliferate membranes. Thus, our results establish a new role for Ino2p in membrane biogenesis that is distinct from its role with Ino4p in phospholipid biosynthesis.

Past work has implicated Ino2p, a member of the bHLH family of transcription factors, as a key regulator of phospholipid biosynthetic genes such as INO1 in response to intracellular levels of inositol and choline. Ino2p was found to be present in a complex that binds to the UASINO of the INO1 promoter when inositol levels were limiting (Lopes and Henry, 1991; Nikoloff and Henry, 1994). Subsequent work identified Ino4p, another HLH protein, as essential for recruiting Ino2p to UASINO (Ambroziak and Henry, 1994). The first six bases of the UASINO consists of the consensus sequence, 5′-CANNTG-3′, recognized by the amphipathic helices of dimerized HLH domains (Ferre-D'Amare et al., 1993; Ma et al., 1994).

To date, Ino2p has only been known to function in phospholipid biosynthesis in conjunction with its putative binding partner, Ino4p. We have defined an essential role for Ino2p in the absence of Ino4p, where the absence of Ino4p appears to enhance membrane proliferation. We propose two models as to how Ino2p might function in membrane biogenesis in the absence of Ino4p: (1) Ino2p may bind to the UASINO or other regulatory region by itself or (2) there may be an alternate binding partner or partners for Ino2p for the transcription of phospholipid biosynthetic genes in response to stimulated membrane biogenesis. We favor the second model, based on reports indicating that in vitro translated Ino2p is unable to bind the INO1 promoter in the absence of Ino4p (Ambroziak and Henry, 1994) as well as studies using the yeast-two-hybrid system, suggesting that neither protein is capable of homodimerization (Schwank et al., 1995).

Ino2p may form a heterodimer with another bHLH transcription factor. Mammalian proteins containing bHLH domains, such as Myc, Mad, Max, and Mxi, have the ability to form multiple heterodimer combinations (Amati and Land, 1994). The DNA-binding regions of Ino2p and Ino4p compared with the HLH-encoding regions of the mammalian Myc family of proteins revealed a high degree of similarity (Nikoloff et al., 1992). In the case of Ino4p, there is some evidence for multiple partners. Yeast-two-hybrid analysis recently revealed interactions with four other known yeast bHLH proteins that have not been implicated in lipid biosynthesis: Pho4p, Rtg1p, Rtg3p, and Sgc1p (Robinson et al., 2000). Ino4p has also been implicated in functioning independently of Ino2p in the synthesis of the sphingolipid biosynthetic enzyme, IPC synthase (Ko et al., 1994). In this article we have presented evidence for Ino2p functioning independently of Ino4p, further indication that yeast HLH transcription factors can participate in multiple roles, possibly in multiple combinations, to regulate diverse biological processes.

The observation that addition of inositol and choline failed to rescue p180-induced membrane proliferation in ino2Δ cells raises the possibility that the assembly of lipid membranes is dependent on more proteins than merely those involved in inositol and choline phospholipid biosynthesis. Several genes involved in fatty acid and sterol biosynthesis as well as inositol transport have been reported as containing putative UASINO elements in their promoters (Greenberg and Lopes, 1996). Functional analyses of many of these genes confirm a role for Ino2p and/or UASINO in their activation (Chirala et al., 1994; Koipally et al., 1996; Grauslund et al., 1999). Our microarray analysis of p180-expressing strains revealed several upregulated genes whose promoters contain known of putative UASINO elements including INO1, GUT1, and SCS3 (unpublished results). ΔCT-GFP–expressing strains harboring deletions in these genes accumulated membranes with abnormal morphologies as well as diminished membrane proliferation as quantified by flow cytometry (L. Block-Alper and D.I. Meyer, unpublished results). Although these membrane defects were not as severe as those observed for ino2Δ cells, it is possible that Ino2p may function to activate a subset of genes whose cumulative enzyme activities are necessary for membrane proliferation.

A recent observation suggests that phospholipid biogenesis is linked to ER perturbation. This has been demonstrated in cells that express high levels of certain ER membrane proteins as well as in cells that undergo an unfolded protein response (UPR) (Cox et al., 1997). The UPR occurs when conditions disruptive to protein folding in the ER, such as the addition of reducing agents, trigger a signaling pathway from the ER that increases transcription of ER-localized chaperones such as KAR2 and PDI1 (Kohno et al., 1993; see Chapman et al., 1998 for review). The signal is transmitted through the ER transmembrane kinase, Ire1p, and cells that are deleted for IRE1 cannot undergo a UPR (Cox et al., 1993). Deletion of IRE1 results in inositol auxotrophy, suggesting that the UPR and phospholipid biosynthesis may be linked (Nikawa and Yamashita, 1992). Moreover, wild-type cells that were induced to undergo a UPR had increased INO1 transcription (Cox et al., 1997). In addition, overexpression of HMG-CoA reductase, which triggers the proliferation of karmellae, impaired growth of ire1Δ cells, suggesting a block in membrane biogenesis, although membrane biogenesis per se was not assessed (Cox et al., 1997).

However, others have shown that ER proliferation is not always linked to the UPR via Ire1p (Menzel et al., 1997; Stroobants et al., 1999). High levels of expression of cytochrome P450 were shown to result in accumulation of ER membranes and a concomitant upregulation of the ER chaperone, KAR2. In P450-expressing cells deleted for IRE1, membrane proliferation was still observed, although KAR2 mRNA failed to be upregulated (Menzel et al., 1997). In p180-expressing cells, increased levels of KAR2 mRNA accompanied ER proliferation (Becker et al., 1999). However, deletion analysis demonstrated Ire1p to dispensable for the production of membranes, as assessed by electron microscopy, as well as for the increased mRNA levels of KAR2 (M. Hyde, L. Block-Alper, and D.I. Meyer, unpublished results). These findings suggest that there may be multiple mechanisms, Ire1p-dependent and -independent, for expanding the ER membrane and increasing its lumenal components.

The regulation of INO2 is becoming increasingly complex. The INO2 promoter contains a UASINO element and has been shown to be autoregulated in response to levels of inositol and choline (Ashburner and Lopes, 1995a). In addition, INO2 appears to be regulated at both the transcriptional and translational levels (Eiznhamer et al., 2001). Transcription of INO2 and INO4 has also been reported as being regulated by the state of protein N-myristoylation (Cok et al., 1998). In this article, we report that INO2 mRNA is induced by expression of an integral ER membrane protein and that its gene product is essential for membrane proliferation. Induction of INO2 in membrane proliferation appears to be independent of the cellular levels of phospholipid precursors, and p180-expression in wild-type cells failed to activate a UASINO-LacZ reporter construct (L. Block-Alper and D. I. Meyer, unpublished results). How then does the induction of ER membrane biogenesis lead to an increase in INO2 mRNA? Is a signal sent from the ER that activates transcription of INO2? Is this signal mediated by a sensor in the ER membrane, such as the UPR is mediated by Ire1p? Further genetic and molecular analysis will help to uncover the mechanisms of INO2 activation during inducible membrane biogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Susan Henry (Carnegie Mellon University) for supplying us with yeast deletion strains and Robin Wright (University of Washington) for HMG expression plasmids; Greg Payne (UCLA) for a critical reading of the manuscript; and the Payne laboratory for materials and assistance with the CPY assay. Flow cytometry technical assistance was provided by Steve Carbonniere at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center and Center for AIDS Research Flow Cytometry Core Facility, UCLA.

Abbreviations used:

- bHLH

basic helix-loop-helix

- PrI

propidium iodide

Appendix

The constructs used for the cloning and plasmid transformation as described by Becker et al. (1999) are diagrammed in Figure A1.

Figure A1.

The p180 constructs used in this study. Full-length and various forms of p180 are shown. Numbers represent amino acid position; black boxes, hydrophobic amino acids predicted to span the ER membrane; and striped boxes, ribosome binding region.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.01–07-0366, Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.01–07-0366.

REFERENCES

- Amati B, Land H. Myc-Max-Mad: a transcription factor network controlling cell cycle progression, differentiation and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:102–108. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambroziak J, Henry SA. INO2 and INO4 gene products, positive regulators of phospholipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, form a complex that binds to the INO1promoter. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15344–15349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner BP, Lopes JM. Autoregulated expression of the yeast INO2 and INO4helix-loop-helix activator genes effects cooperative regulation on their target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995a;15:1709–1715. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner B P, Lopes J M. Regulation of yeast phospholipid gene expression in response to inositol involves two superimposed mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995b;92:9722–9726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker F, Block-Alper L, Nakamura G, Harada J, Wittrup KD, Meyer DI. Expression of the 180-kD ribosome receptor induces membrane proliferation and increased secretory capacity in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:273–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman R, Sidrauski C, Walter P. Intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:459–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Kiang S. Regulation of terminal differentiation of human B-cells by IL-6. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;194:189–198. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79275-5_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cok SJ, Martin CG, Gordon JI. Transcription of INO2 and INO4 is regulated by the state of protein N-myristoylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2865–2872. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo MC, Crawford ME, Hirschman JE, Kranz J E, Olsen P, Robertson LS, Skrzypek MS, Braun BR, Hopkins KL, Kondu P, Lengieza C, Lew-Smith JE, Tillberg M, Garrels JI. YPD™, PombePD™, and WormPD™ model organism volumes of the BioKnowledge™ library, an integrated resource for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:75–79. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo MC, Hogan JD, Cusick ME, Davis BP, Fancher AM, Hodges P E, Kondu P, Lengieza C, Lew-Smith JE, Lingner C, Roberg-Perez KJ, Tillberg M, Brooks JE, Garrels JI. The Yeast Proteome Database (YPD) and Caenorhabditis elegansProteome Database (WormPD): comprehensive resources for the organization and comparison of model organism protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:73–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic recticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Chapman RE, Walter P. The unfolded protein response coordinates the production of endoplasmic recticulum protein and endoplasmic recticulum membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1805–1814. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirala SS, Zhong Q, Huang W, Al-Feel W. Analysis of FAS3/ACC regulatory region of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of a functional UASINO and sequences responsible for fatty acid mediated repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:412–418. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.3.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson MR, Henry SA. Inositol-requiring mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1975;80:23–40. doi: 10.1093/genetics/80.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallner G, Siekvitz P, Palade GE. Biogenesis of endoplasmic recticulum membranes I. Structural and chemical differentiation in developing rat hepatocyte. J Cell Biol. 1966a;30:73–96. doi: 10.1083/jcb.30.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallner G, Siekvitz P, Palade GE. Biogenesis of endoplasmic recticulum membranes II. Synthesis of constitutive microsomal enzymes in developing rat hepatocyte. J Cell Biol. 1966b;30:97–117. doi: 10.1083/jcb.30.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deere D, Shen J, Vesey G, Bell P, Bissinger P, Veal D. Flow cytometry and cell sorting for yeast viability assessment and cell selection. Yeast. 1998;14:147–160. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<147::AID-YEA207>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue TF, Henry SA. Inositol mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: mapping the ino1 locus and characterizing alleles of ino1, ino2, and ino4loci. Genetics. 1981;98:491–503. doi: 10.1093/genetics/98.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiznhamer DA, Ashburner BP, Jackson JC, Gardenour KR, Lopes JM. Expression of the INO2 regulatory gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeis controlled by positive and negative promoter elements and an upstream open reading frame. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1395–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Kwast L, van den Berg M, Snyder WB, Distel B, Subramani S, Tabak HF. Overexpression of Pex15p, a phosphorylated peroxisomal integral membrane protein required for peroxisome assembly in S. cerevisiae, causes proliferation of the endoplasmic recticulum membrane. EMBO J. 1997;16:7326–7341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre-D'Amare AR, Prendergast GC, Ziff EB, Burley SK. Recognition by Max of its cognate DNA through a dimeric b/HLH/Z domain. Nature. 1993;363:38–45. doi: 10.1038/363038a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giberson, R.T., and Demaree, R.S., Jr. (1999). Microwave processing techniques for electron microscopy: a four hour protocol. In: Electron Microscopy Methods and Protocols, ed. M.A. Nasser Hajibagheri, Methods in Molecular Biology vol. 117, NJ: Humana Press, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grauslund M, Lopes JM, Ronnow B. Expression of GUT1, which encodes glycerol kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is controlled by the positive regulators Adr1p, Ino2p and Ino4p and the negative regulator Opi1p in a carbon-source dependent fashion. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4391–4398. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves JA, Henry SA. Regulation of the yeast INO1 gene: the products of the INO2, INO4, and OPI1regulatory genes are not required for repression in response to inositol. Genetics. 2000;154:1485–1495. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.4.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg ML, Lopes JM. Genetic regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.1-20.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C, Fink GR. Methods in Enzymology: Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. New York: Academic Press; 1991. , 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CL, Romano P, Roe S, Tontonoz P. INO2, a regulatory gene in yeast phospholipid biosynthesis, affects nuclear segregation and bud pattern formation. Cell Mol Biol Res. 1993;39:561–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SA, Patton-Vogt JL. Genetic regulation of phospholipid metabolism: yeast as a model eukaryotes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;61:133–179. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth NM, Goetsch L, Byers B. The HOP1gene encodes a meiosis specific component of yeast chromosomes. Cell. 1990;61:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovcic S, Getz G, Rabinowitz M, Jakob H, Swift H. Cardiolipin contents of wild type and yeast mutants in relation to mitochondrial function and development. J Cell Biol. 1971;48:490–502. doi: 10.1083/jcb.48.3.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CA, Schekman R. Distinct sects of SEC genes govern transport vesicle formation and fusion early in the secretory pathway. Cell. 1990;61:723–733. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90483-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J, Cheah S, Fischl AS. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol: ceramide phosphoinositol transferase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5181–5183. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.5181-5183.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno K, Normington K, Sambrook J, Gething MJ, Mori K. The promoter region of the yeast KAR2(BiP) gene contains a regulatory domain that responds to the presence of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic recticulum. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:877–890. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koipally J, Ashburner BP, Bachhawat N, Gill T, Hung G, Henry SA, Lopes JM. Functional characterization of the repeated UASINO element in the promoters of the INO1 and CHO2 genes of yeast. Yeast. 1996;12:653–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19960615)12:7%3C653::AID-YEA953%3E3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning AJ, Roberts CJ, Wright RL. Different subcellular localization of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeHMG CoA reductase isozymes at elevated levels corresponds to distinct endoplasmic recticulum membrane proliferations. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:769–789. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K, McGraw P. Dual control of inositol transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by irreversible inactivation of permease and regulation of permease synthesis by INO2, INO4, and OPI1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2245–2251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley R, Leung E, Morris C, Berg R, McDonald M, Weaver A, Parry DA, Ni J, Su J, Gentz R, Spurr N, Krissansen GW. Identification of multiple forms of 180-kDa ribosome receptor in human cells. DNA Cell Biol. 1998;17:449–460. doi: 10.1089/dna.1998.17.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshutz RJ, Fodor SP, Gingeras TR, Lockhart DJ. High density synthetic oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1 Suppl):20–24. doi: 10.1038/4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart DJ, Winzeler EA. Genomics, gene expression and DNA arrays. Nature. 2000;405:827–836. doi: 10.1038/35015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes JM, Henry SA. Interaction of trans and cis regulatory elements in the INO1 promoter of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3987–3994. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma PC, Rould MA, Weintraub H, Pabo CO. Crystal structure of MyoD bHLH domain-DNA complex: perspectives on DNA recognition and implications for transcriptional activation. Cell. 1994;77:451–459. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Springs Harbor, NY: Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory; 1982. pp. 7.43–7.45. [Google Scholar]

- Menzel R, Vogel F, Kargel E, Schunck W-H. Inducible membranes in yeast: relation to the unfolded-protein-response pathway. Yeast. 1997;13:1211–1229. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199710)13:13<1211::AID-YEA168>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikawa JI, Yamashita S. IRE1 encodes a putative protein kinase containing a membrane spanning domain and is required for inositol prototrophy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1441–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoloff DM, McGraw P, Henry SA. The INO2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeencodes a helix-loop-helix protein that is required for phospholipid synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3253. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.12.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoloff DM, Henry SA. Functional characterization of the INO2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7402–7411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish ML, Sengstag C, Rine JD, Wright RL. Identification of the sequences in HMG-CoA reductase required for karmellae assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1535–1547. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.11.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GH, Knobel SM, Sharif WD, Kain SR, Piston DW. Use of the green fluorescent protein and its mutants in quantitative fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 1997;73:2782–2790. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78307-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KA, Lopes JM. The promoter of the yeast INO4regulatory gene: a model of the simplest yeast promoter. J Bacteriol. 2000a;182:2746–2752. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2746-2752.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KA, Lopes JM. Saccharomyces cerevisiaebasic helix-loop-helix proteins regulate diverse biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000b;28:1499–1505. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KA, Koepke JI, Kharodawala M, Lopes JM. A network of yeast basic helix-loop-helix interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4460–4466. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.22.4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothblatt JA, Deshaies RJ, Sanders SL, Daum G, Schekman R. Multiple genes are required for proper insertion of secretory proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(6 Pt 1):2641–2652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunck WH, Vogel F, Gross B, Kargel E, Mauersberger S, Kopke K, Gengnagel C, Muller HG. Comparison of two cytochromes P-450 from Candida maltosa: primary structures, substrate specificities and effects of their expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiaeon the proliferation of the endoplasmic reticulum. Eur J Cell Biol. 1991;55:336–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwank S, Ebbert R, Rautenstrauss K, Schweizer E, Schueller H-J. Yeast transcriptional activator INO2 interacts as an Ino2p/Ino4p basic helix-loop-helix heteromeric complex with the inositol/choline-responsive element necessary for expression of phospholipid biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:230–237. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroobants AK, Hettema EH, van den Berg M, Tabak HF. Enlargement of the endoplasmic recticulum membrane in Saccharomyces cerevisiaeis not necessarily linked to the unfolded protein response via Ire1p. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:210–214. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyn J, Hibbs AR, Sanz P, Crowe J, Meyer DI. In vivo and in vitro analysis of ptl1, a yeast ts mutant with a membrane-associated defect in protein translocation. EMBO J. 1988;7:4347–4353. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C, Blank M, Strohmann B, Schueller H-J. Overproduction of the Opi1 repressor inhibits transcriptional activation of structural genes required for phospholipid biosynthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:843–854. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10A<843::AID-YEA424>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanker EE, Sun Y, Savitz AJ, Meyer DI. Functional characterization of the 180-kD ribosome receptor in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:29–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsbach K, Payne GS. Vps1p a member of the dynamin GTPase family, is necessary for Golgi membrane protein retention in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1993;12:3049–3059. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright R, Basson M, D'Ari L, Rine J. Increased amounts of HMG-CoA reductase induce “Karmellae”: a proliferation of stacked membrane pairs surrounding the yeast nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:101–114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Matern HT, Gallwitz D. Specific binding to a novel and essential Golgi membrane protein (Yip1p) functionally links the transport GTPases Ypt1p and Ypt31p. EMBO J. 1998;17:4954–4963. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]