Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a common aggressive cancer that originates in the brain, which has a poor prognosis. It is therefore crucial to understand its underlying genetic mechanisms in order to develop novel therapies. The present study aimed to identify some prognostic markers and candidate therapeutic targets for GBM. To do so, RNA expression levels in tumor and normal tissues were compared by microarray analysis. The differential expression of RNAs in normal and cancer tissues was analyzed, and a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network was constructed for pathway analysis. The results revealed that RNA expression patterns were considerably different between normal and tumor samples. A ceRNA network was therefore constructed with the differentially expressed RNAs. ETS variant 5 (ETV5), myocyte enhancer factor 2C and ETS transcription factor (ELK4) were considerably enriched in the significant pathway of ‘transcriptional misregulation in cancer’. In addition, prognostic analysis demonstrated that ETV5 and ELK4 expression levels were associated with the survival time of patients with GBM. These results suggested that ELK4 and ETV5 may be prognostic markers for GBM, and that their microRNAs may be candidate therapeutic targets.

Keywords: glioblastoma, microarray analysis, ceRNA network, prognostic marker, therapeutic target

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are a class of small noncoding RNAs that serve key roles in various types of biological processes. Competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) were recently defined as a group of RNAs that competes for shared miRNA targets and affects the biological functions of miRNAs (1). It has been reported that ceRNAs serve regulatory roles in gene expression, and are involved in the pathogenesis of cancer and other diseases (2). Therefore, focusing on ceRNA networks is important to understand the underlying mechanisms of cancer progression.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a common aggressive cancer that originates in the brain. Early stage symptoms of GBM are similar to those of a stroke, but they worsen rapidly (3). The survival time of patients after diagnosis is between 12 and 15 months, and only 3–5% of patients survive for 5 years following therapy (4). Current therapies include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation; however, GBM maintains a poor prognosis. It is therefore important to study the underlying genetic mechanisms of GBM. Identifying prognostic markers of GBM will also aid understanding of the mechanism underlying metastasis and may lead to the discovery of novel therapeutic targets. Identifying the ceRNA network in GBM may provide a novel perspective for understanding the biological mechanisms of the disease.

In the present study, RNA microarray analysis was performed on tumors from patients with GBM, and a ceRNA network based on the GBM datasets was designed. The genes that were highlighted in the dysfunctional pathways may serve key roles in GBM progression. Subsequently, a functional analysis of mRNAs from the ceRNA network was performed, and focused on the significant pathway-associated genes and miRNAs.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Tumor specimens and paired adjacent healthy tissues were obtained during surgical resection performed at Luhe Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University (Beijing, China) between September 2016 and December 2016. The patients with GBM included in the presented consisted of one female and two males (age, 60±7.21 years). All surgically removed tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C within 30 min. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Luhe Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University (Beijing, China) and all patients provided informed consent prior to the study.

Microarray RNA expression

Total RNA was isolated using a TRIzol® Plus RNA Purification kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), according to the supplier's protocol. RNA quality and concentration were assessed using an ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmingtom, DE, USA). Microarrays were performed using a GeneChip® WT Pico Reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, total RNA (>1 µg) was used for cDNA synthesis, which was performed with WT Pico Reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cDNA was fragmented with uracil-DNA glycosylase and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 at the unnatural dUTP residues, and then labeled with biotin and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) using the Affymetrix DNA Labeling Reagent (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The samples were hybridized with the GeneChip® Hybridization, Wash, and Stain kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After washing, the arrays were scanned with a GeneChip® Scanner 3000 7G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Testing for correlation of expression levels between samples

The correlation and reliability of RNA expression between samples were evaluated. Based on RNA expression, a principal components analysis (PCA) was conducted for each sample using the psych package (version 1.7.8) (5) in R 3.4.1 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/index.html) in order to evaluate whether obvious outliers were present in the samples. In addition, Pearson correlation coefficients (PCC) were calculated between samples using the cor function in R 3.4.1 (https://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-devel/library/stats/html/cor.html).

Data preprocessing and differential expression analysis

The raw data were preprocessed by oligo (version 1.40.2) (6) in R 3.4.1, which included original data transformation, unwanted data elimination, background correction and normalization. RNA data were annotated based on the human whole genome (GRCh38.p10), provided by the GENCODE database (https://www.gencodegenes.org).

The differentially expressed mRNAs (DE-mRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (DE-lncRNAs), miRNAs (DE-miRNAs) and circular RNAs (DE-circRNAs) between the GBM group and controls were identified using the limma package (version 3.32.5) (7) (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html). P<0.05 and |log fold change (FC)|>1 were defined as cutoff values. The DE-mRNAs, DE-lncRNAs, DE-miRNAs and DE-circRNAs were clustered based on the expression values obtained by the pheatmap package (version 1.0.8) (8) in R (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html).

Function and pathway analysis of DE-mRNAs

The Gene Ontology (GO) functions and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways closely associated with DE-mRNAs were predicted by the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) online tool (9) (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/).

If the number of genes enriched in a GO term were exact, P-values were calculated using the Fisher exact test based on hypergeometric distribution. When 2nf ≤ n, the P-value was calculated as follows:

where nf, number of DE genes enriched in the GO term; n, total number of genes enriched in the GO term; Nf, total number of DE genes that are either enriched or not enriched in the GO term; N, total number of genes in all conditions; N-n, total number of genes not enriched in the GO term; pF, P-value obtained by Fisher exact test; pn, P-value of the GO term; and x, random variable.

Prediction of the disease-related RNAs

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) (10) is a biological method used to design correlation networks based on high throughput expression data. WGCNA can be employed to find clusters of genes closely correlated and analyze the correlation between RNA and disease. In the present study, DE-mRNAs, DE-lncRNAs, DE-miRNAs and DE-circRNAs were analyzed with the WGCNA package (11) in R.

Prediction of lncRNA-miRNA, circRNA-miRNA and miRNA-mRNA interactions

Based on the differentially expressed RNA analysis, the interactions between lncRNA and miRNA were analyzed by miRcode version 11 (http://www.mircode.org/) (12). The circRNA-miRNA interactions were predicted by the starBase database version 2.0 (13) (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/index.php). The |correlation coefficient|>0.6 obtained by WGCNA analysis was defined as the criterion for screening the lncRNA-miRNA and circRNA-miRNA interactions. The interaction network was visualized by Cytoscape 3.3 (14) (http://www.cytoscape.org/).

The target genes regulated by DE-miRNAs were predicted by miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do) (15) and TargetScan (16) Release 7.1 (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71/). The miRNA-mRNA interactions with reverse expression were collected for network construction using Cytoscape 3.3. Subsequently, the target genes of the miRNAs were subjected to GO function and pathway analysis using the DAVID online tool.

ceRNA network construction

Based on the lncRNA-miRNA, circRNA-miRNA and miRNA-mRNA interactions predicted, a ceRNA network was constructed. Pathway analysis was performed for the mRNAs in the ceRNA network. The significant pathways and genes were further analyzed.

Prognosis analysis

A total of 305 brain tumor datasets, including 128 GBM, 46 oligodendrocytomas, 94 astrocytomas and 37 mixed brain tumor samples were downloaded from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA;http://www.cgga.org.cn/) database. The 128 GBM samples with prognostic information were collected for further analysis. The significant pathway-related genes were subjected to Kaplan-Meier curve analysis (17) based on the expression values of the 128 GBM samples with the application of the survival package (version 2.41.3; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/index.html) in R.

Results

Correlation between the gene expression profiles of samples

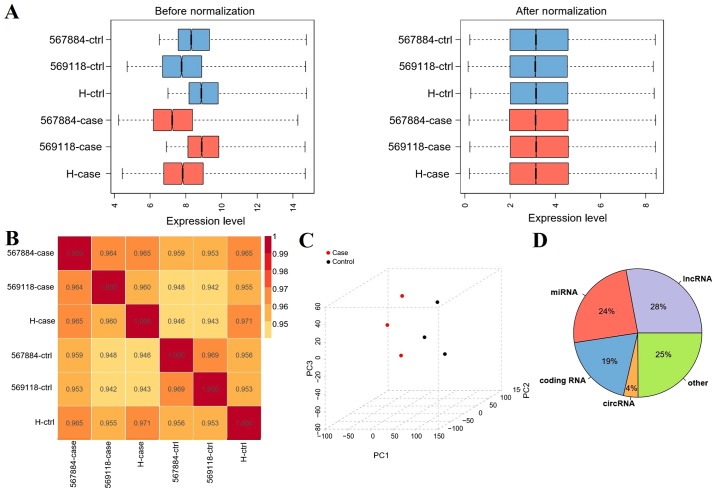

After data preprocessing, the expression data were normalized (Fig. 1A). PCC between samples was calculated. If the correlation coefficient was close to 1, this indicated that the expression patterns between samples were similar. As shown in Fig. 1B, all PCCs ranged between 0.95 and 1, which indicated that the expression pattern correlations between samples were high.

Figure 1.

RNA analysis of GBM and normal control samples. (A) Box plot of RNA expression patterns before and after normalization. Blue box, normal control samples; red box, GBM samples. (B) Correlations between expression patterns across samples. (C) PCA analysis of RNA expression levels. Black, control samples; red, tumor samples. (D) Distribution of RNA classified statistics chart. Ctrl, control; circRNA, circular RNA; GBM, glioblastoma; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA, microRNA.

PCA analysis demonstrated that there were no outliers

The sample distribution was relatively centralized, particularly for samples in the same group (Fig. 1C). After RNA data annotation, a total of 135,750 probes with expression signals were detected, including 28% lncRNAs, 24% miRNAs, 4% circRNAs and 19% mRNAs (Fig. 1D).

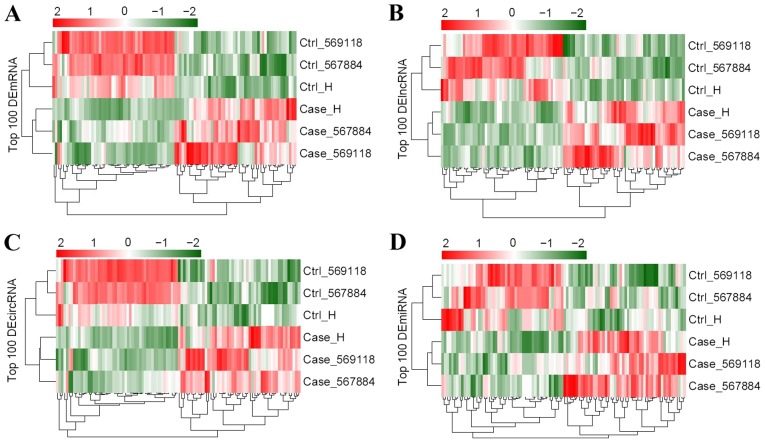

Identification of differentially expressed RNAs

According to the cutoff value, a total of 987 DE-mRNAs, 2,879 DE-lncRNAs, 702 DE-circRNAs and 44 DE-miRNAs were found in tumor samples compared with controls. Bidirectional hierarchical cluster analysis illustrated that the expression patterns of DE-mRNAs, DE-lncRNAs, DE-circRNAs and DE-miRNAs were considerably different between GBM and control samples (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Bidirectional hierarchical clustering of (A) DE-mRNA, (B) DE-lncRNA, (C) DE-circRNA and (D) DE-miRNA. Ctrl, control; DE-mRNAs, differentially expressed mRNAs; DE-lncRNAs, differentially expressed long non-coding RNAs; DE-miRNAs, differentially expressed microRNAs; DE-circRNAs, differentially expressed circular RNAs.

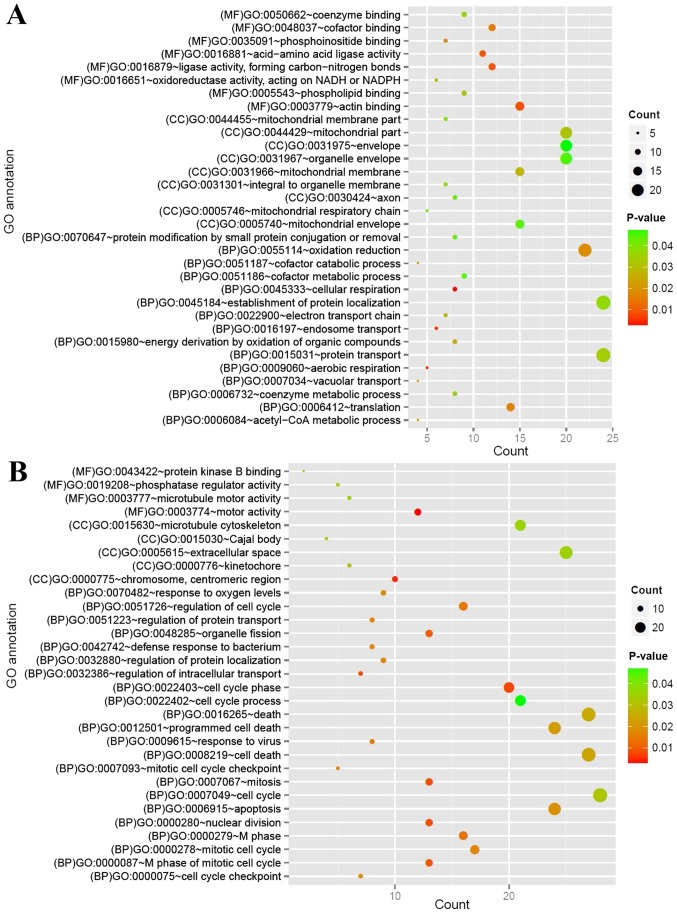

DE-mRNAs GO functions and pathways

GO function and KEGG pathway analyses were performed for the up and downregulated mRNAs. The downregulated mRNAs were considerably enriched for 32 GO terms [15 biological processes (BP), 9 cellular components (CC) and 8 molecular functions (MF)], including ‘GO:0045333~cellular respiration’ (BP), ‘GO:0016197~endosome transport’ (BP) and ‘GO:0016881~acid-amino acid ligase activity’ (MF) (Fig. 3A). The upregulated mRNAs were closely associated with 31 GO terms (22 BP, 5 CC and 4 MF), including ‘GO:0022403~cell cycle phase’ (BP), ‘GO:0000775~chromosome, centromeric region (CC)’ and ‘GO:0003774~motor activity’ (MF) (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Function analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs. (A) GO function analysis of downregulated mRNAs. (B) GO function analysis of upregulated mRNAs. Circle size represents the count of mRNAs, and the color from green to red represents the P-value, from small to large. BP, biological process; CC, cellular components; GO, Gene Ontology; MF, molecular function.

Downregulated mRNAs were considerably enriched in four pathways: ‘hsa05010: Alzheimer's disease’; ‘hsa00970: Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis’; ‘hsa04740: Olfactory transduction’; and ‘hsa04130: SNARE interactions in vesicular transport’. The upregulated mRNAs were considerably enriched in seven pathways, including: ‘hsa00601: Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis’; ‘hsa04110: Cell cycle’; ‘hsa04664: Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway’; and ‘hsa00380: Tryptophan metabolism’ (Table I).

Table I.

Significant pathways enriched by mRNAs.

| A, Upregulated mRNAs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway | Count | P-value | Genes |

| hsa00601:Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis | 4 | 0.029075 | GCNT2, B3GNT5, B3GALT5, ST8SIA1 |

| hsa04110:Cell cycle | 8 | 0.045249 | RAD21, EP300, TGFB3, BUB1B, SMC1A, GADD45A, CDC25A, TGFB2 |

| hsa00603:Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis | 3 | 0.045376 | B3GALT5, HEXA, ST8SIA1 |

| hsa04664:Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | 6 | 0.045974 | IL5, PLCG1, PLA2G2A, IL13, VAV2, PLA2G2F |

| hsa04140:Regulation of autophagy | 4 | 0.046813 | IFNA2, PRKAA1, IFNA8, IFNA17 |

| hsa00511:Other glycan degradation | 3 | 0.046845 | MAN2C1, HEXA, NEU1 |

| hsa00380:Tryptophan metabolism | 4 | 0.049342 | TDO2, IDO2, WARS2, INMT |

| B, Downregulated mRNAs | |||

| Pathway | Count | P-value | Genes |

| hsa05010:Alzheimer's disease | 10 | 0.008332 | NOS1, UQCRC1, CASP9, NDUFA8, COX7B2, SNCA, BACE1, PPP3R1, NDUFA10, ITPR1 |

| hsa00970:Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 4 | 0.0458 | NARS, PSTK, CARS2, IARS2 |

| hsa04740:Olfactory transduction | 14 | 0.046398 | OR4K5, OR5P3, OR4K2, OR5M11, OR6C74, OR1E2, OR2K2, PRKG1, OR2AE1, OR4A5, OR1S1, OR4C15, OR2T33, OR14I1 |

| hsa04130:SNARE interactions in vesicular transport | 4 | 0.048063 | VAMP7, SNAP47, GOSR1, STX1B |

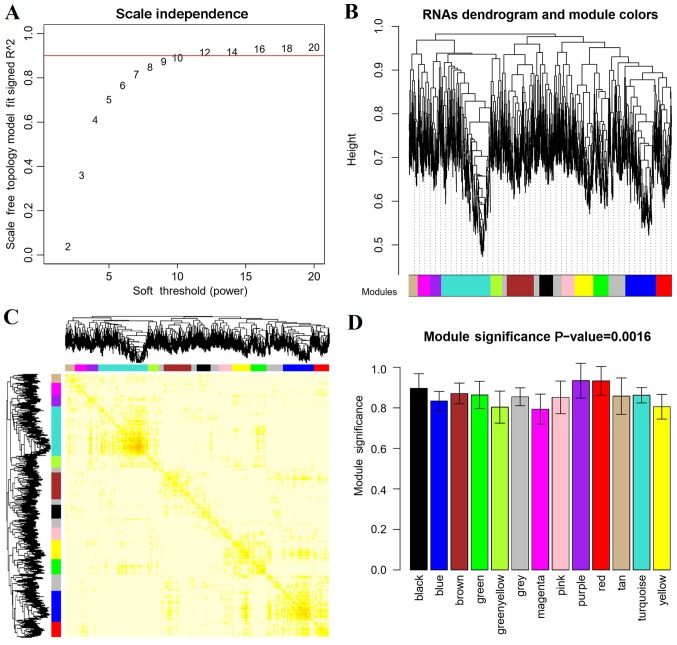

Disease-related RNAs and modules based on WGCNA analysis

In order to screen the disease-related RNAs, correlation analysis was performed based on the WGCNA algorithm. As shown in Fig. 4A, when (correlation coefficient)2 was up to 0.9, the weight parameter power was 12. Power=12 was used for the RNA dendrogram and module analysis, and other parameters were set as gene count=100 and cutHeight=0.95. A total of 13 modules were obtained (Fig. 4B) and the correlation dendrogram of modules was presented in Fig. 4C. The correlations between RNA expression and disease state (disease/control) were calculated. All modules were significantly correlated with disease (P=0.0016) and the correlation coefficient of each module to disease was >0.8 (Fig. 4D and Table II).

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis was performed using the weighted gene co-expression network analysis algorithm to screen the disease-related RNAs. (A) Diagram of power selection. (B) Dendrogram of modules. (C) Dendrogram of correlation across modules. (D) Disease-related modules.

Table II.

Correlation and RNA composition of each module with disease.

| Module color | Correlation with disease | Total RNAs | lncRNA | mRNA | miRNA | circRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 0.8981 | 188 | 100 | 53 | 6 | 29 |

| Blue | 0.8367 | 423 | 220 | 117 | 6 | 80 |

| Brown | 0.8756 | 372 | 213 | 88 | 15 | 56 |

| Green | 0.8619 | 210 | 114 | 60 | 2 | 34 |

| Green/yellow | 0.8017 | 157 | 89 | 40 | 3 | 25 |

| Grey | 0.8573 | 492 | 267 | 123 | 23 | 79 |

| Magenta | 0.7969 | 165 | 87 | 41 | 7 | 30 |

| Pink | 0.8559 | 178 | 92 | 49 | 2 | 35 |

| Purple | 0.9369 | 158 | 74 | 51 | 3 | 30 |

| Red | 0.9365 | 210 | 103 | 64 | 5 | 38 |

| Tan | 0.8589 | 126 | 80 | 26 | 4 | 16 |

| Turquoise | 0.8611 | 680 | 327 | 201 | 24 | 128 |

| Yellow | 0.8027 | 260 | 125 | 74 | 6 | 55 |

circRNA, circular RNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA, microRNA.

lncRNA-miRNA, circRNA-miRNA and miRNA-mRNA interactions

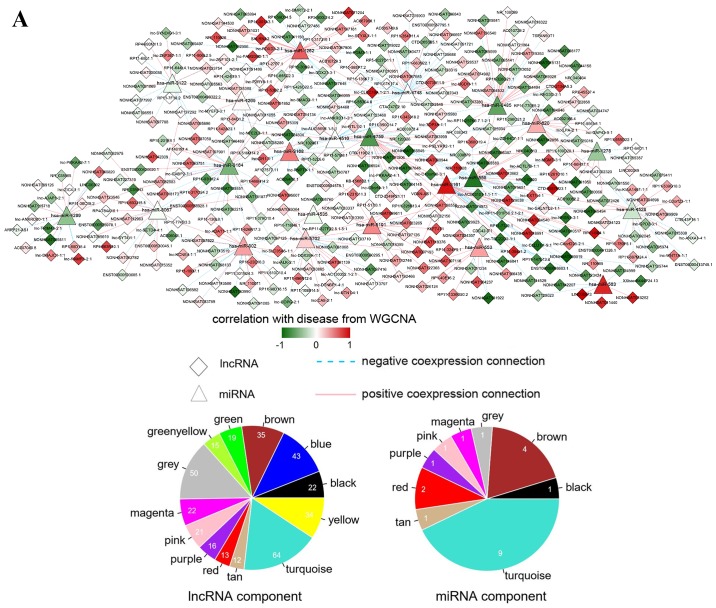

A total of 55,064 lncRNA-miRNA interactions were predicted by the miRcode database. Based on WGCNA analysis, the lncRNA-miRNA pairs with |correlation coefficient|>0.6 were collected for the lncRNA-miRNA interaction network. As shown in Fig. 5A, the lncRNA-miRNA interaction network was constructed with 450 lncRNA-miRNA interaction pairs.

Figure 5.

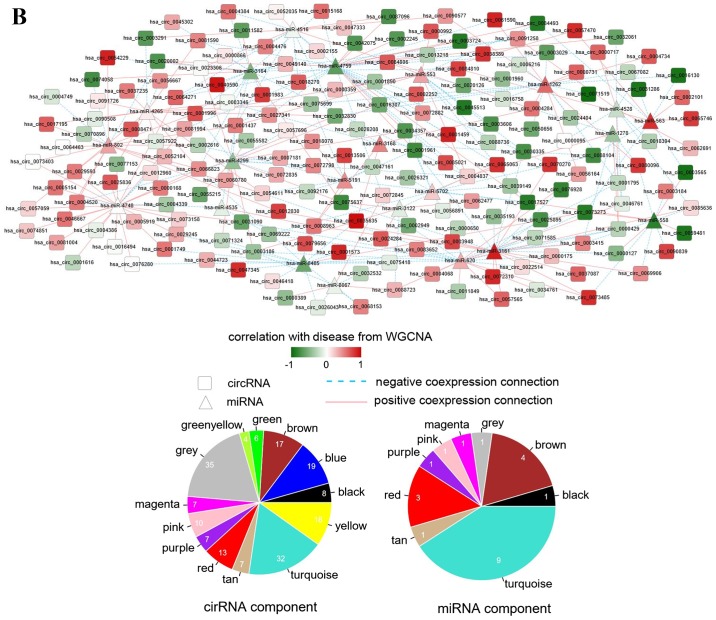

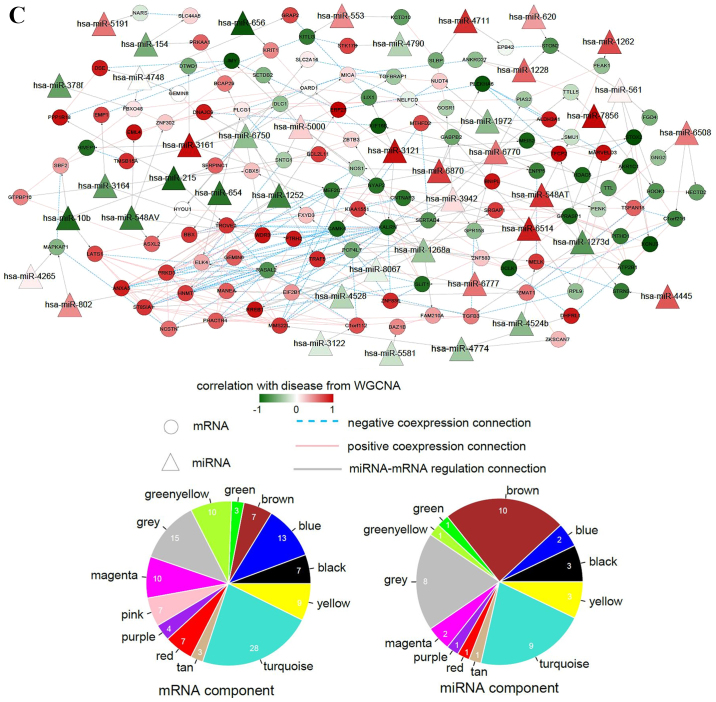

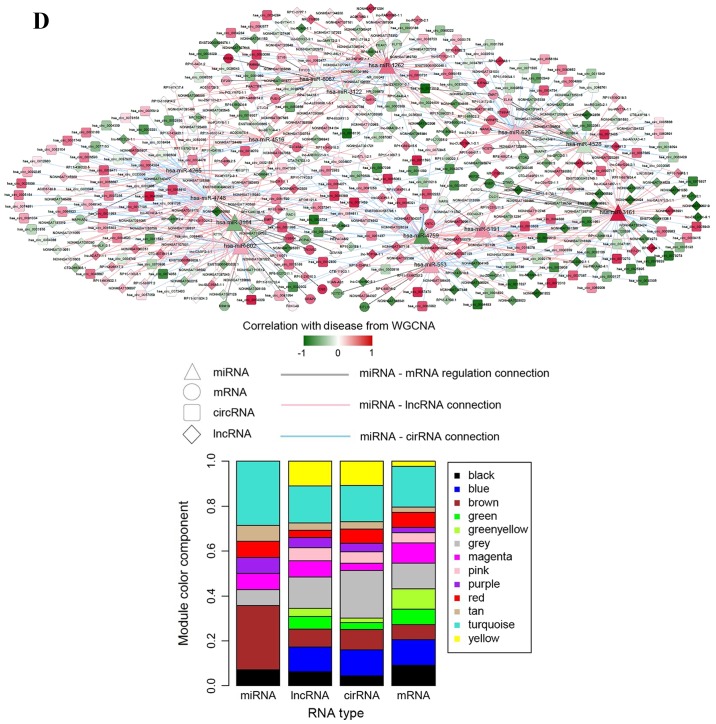

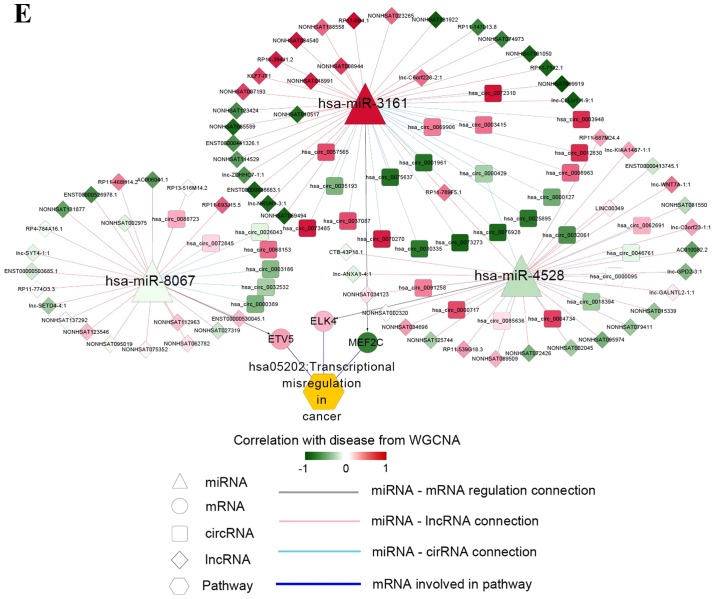

Interaction networks. (A) lncRNA-miRNA interaction network: Triangle node represents miRNA and rhombus node represents lncRNA; color change from green to red represents negative correlation to positive correlation with disease based on WGCNA. Red line represents positive correlation and blue line represents negative correlation. The pie chart shows the distribution of nodes in WGCNA modules. (B) circRNA-miRNA interaction network: Triangle node represents miRNA and square node represents circRNA. (C) miRNA-mRNA interaction network: Triangle node represents miRNA and circle node represents mRNA. (D) ceRNA regulatory network: Triangle node represents miRNA, square node represents circRNA, rhombus node represents lncRNA and circle node represents mRNA. (E) Subnetwork of ceRNA involved with ETV5, MEF2C and ELK4. circRNA, circular RNA; ELK4, ETS transcription factor; ETV5, ETS variant 5; KM, Kaplan-Meier; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; MEF2C, myocyte enhancer factor 2C; miRNA/miR, microRNA; WGCNA, weighted gene co-expression network analysis.

Based on the information deposited in the starBase database, 20,480 circRNA-miRNA interactions were collected, among which 313 pairs had a |correlation coefficient|>0.6. The circRNA-miRNA interaction network comprised 183 circRNAs and 22 miRNAs connected with 313 edges (Fig. 5B).

A total of 8,275 and 15,573 miRNA-mRNA interactions were predicted through miRanda and the TargetScan database, respectively. Among the 425 overlapping interactions, 151 interaction pairs had inverse expression. In addition, 209 mRNA interaction pairs with a |correlation coefficient|>0.6 were collected to construct the miRNA-mRNA interaction network. The network presented 163 nodes (42 miRNAs and 121 mRNAs) and 360 edges (151 miRNA-mRNA interactions and 209 mRNA-mRNA interactions) (Fig. 5C). miRNAs and mRNAs in the network were mainly the members in the turquoise and brown modules by WGCNA.

ceRNA regulatory network construction

Based on the aforementioned RNA interactions obtained, a ceRNA network comprising lncRNA, circRNA, miRNA and mRNA was constructed (Fig. 5D). The ceRNA network contained 487 nodes (273 lncRNAs, 156 circRNAs, 14 miRNAs and 44 mRNAs) and 602 edges (317 lncRNA-miRNA interactions, 234 circRNA-miRNA interactions and 51 miRNA-mRNA interactions). The lncRNA, circRNA and mRNA nodes were mainly members of the turquoise disease-related module in WGCNA. The miRNAs were mainly from the turquoise and brown modules.

All mRNAs in the ceRNA network were subjected to pathway analysis, and six significant KEGG pathways were enriched, including ‘has05202:Transcriptional misregulation in cancer’, ‘has00603:Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis’ and ‘hsa04010: MAPK signaling pathway’. The differentially expressed ETS variant 5 (ETV5), myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) and ETS transcription factor (ELK4) were enriched in the ‘transcriptional misregulation in cancer pathway’ (Table III). The ceRNA networks associated with ETV5, MEF2C and ELK4 were further analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5E, ETV5, MEF2C and ELK4 were regulated by hsa-miR-8067, hsa-miR-3161 and hsa-miR-4528, respectively.

Table III.

Significant pathways enriched by mRNAs in the ceRNA network.

| Term | ID | P-value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional misregulation in cancer | hsa05202 | 0.0008963 | ETV5, MEF2C, ELK4 |

| RNA transport | hsa03013 | 0.0139342 | EIF2B1, GEMIN8 |

| Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis | hsa00603 | 0.0153436 | DSE, ST8SIA1 |

| MAPK signaling pathway | hsa04010 | 0.0288689 | MEF2C, ELK4 |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | hsa00520 | 0.0492771 | CYB5R4 |

| Notch signaling pathway | hsa04330 | 0.0492771 | NCSTN |

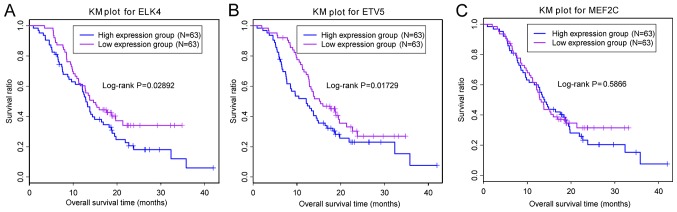

Determination of prognostic markers

Prognostic marker analysis was performed for ETV5, MEF2C and ELK4. The samples were classified into high and low expression groups based on the expression median of the given gene. The association between gene expression and prognosis was analyzed. Fig. 6 demonstrated that low expression of ETV5 and ELK4 were significantly associated with a good prognosis, whereas MEF2C expression was not associated with prognosis.

Figure 6.

KM curve analysis of the association between the expression of (A) ELK4, (B) ETV5 and (C) MEF2C, and prognosis. The purple and blue lines represent low and high expression levels, respectively. ELK4, ETS transcription factor; ETV5, ETS variant 5; KM, Kaplan-Meier; MEF2C, myocyte enhancer factor 2C.

Discussion

ceRNAs serve an important role in regulating gene expression. It has been reported that perturbations in ceRNA networks are closely associated with cancer progression (1). GBM is a common aggressive brain cancer, known to have a poor prognosis and limited available therapies. Therefore, ceRNA networks may provide novel tools to understand the underlying mechanisms of GBM and discover potential novel therapeutic targets. In the present study, RNA microarray data were obtained from GBM tumor and paired control tissues. Based on the RNA expression datasets, a ceRNA network was constructed.

The differential expression of RNAs between GBM and control samples observed suggested that DE-RNAs may be important for cancer progression. For instance, it has been demonstrated that reducing SH2-containing-inositol-5-phosphatase 2 expression affects the control of cell migration in glioblastoma (18). In addition, inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and 2 leads to suppression of GBM cell proliferation (19). It is well known that miRNAs are a class of small lncRNAs, which negatively regulate gene expression at the mRNA level (20). Some ceRNAs, including lncRNAs and circRNAs, share the target binding sites of miRNAs and competitively bind in order to affect gene expression and biological processes (2). The ceRNA networks contain transcripts that share miRNA response elements targeted by miRNAs (1). The ceRNA network analysis performed in the present study revealed that ‘transcriptional misregulation in cancer’ was a markedly altered pathway in GBM.

ETV5, ELK4, and MEF2C are mRNAs that exhibited significant differential expression in the most significantly enriched pathways. ETV5 is a member of the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) family of transcription factors, and its dysregulation is associated with prostate (21) and endometrial cancer (22). A recent study revealed that ETS pathways are perturbed in the initiation and maintenance of glioma (23). In addition, Li et al reported that ETV5 serves a critical role in perinatal gliogenesis (24). It has been reported that many ETS family members are upregulated in Kras, Hras and Erbb tumors (23). ETV5 is also involved in tumor initiation and gliogenesis regulation (24). ETV5 may therefore serve an important role in GBM development. In addition, prognostic analysis of ETV5 expression in 128 brain nerve tumor samples revealed that low expression was considerably associated with a good prognosis, which suggested that high expression of ETV5 may be a risk factor for GBM.

High expression of ELK4 was also revealed to be a risk factor for GBM by prognostic analysis. Similar to ETV5, ELK4 is an ETS-domain transcription factor. ETS transcription factors serve regulatory roles in gene expression and various biological processes, including cellular proliferation, differentiation, development and apoptosis (25). ETS transcription factors have previously been suggested as candidate therapeutic targets for cancer (26). In addition, ETS gene rearrangement and fusion are frequently observed in prostate cancer (27,28). The solute carrier family 45, member 3-ELK4 is a novel fusion transcript highly expressed in patients with prostate cancer (29). Some ETS genes, including ETV1, ETV4, ETV5 and ELK4, have been reported to be rearranged in prostate cancer (28). In addition, ELK4 promotes apoptosis in glioma by inhibiting the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein myeloid cell leukemia-1 (30). Downregulation of ELK4 inhibited GBM tumor formation and ELK4 was defined as a novel target for GBM therapy (30). In the present study, ELK4 was considerably upregulated in GBM tumor samples, and these high expression levels were associated with a poor prognosis, which was consistent with previous findings. Altogether, these results suggested that ELK4 may serve a critical role in GBM formation.

The ceRNA network analysis revealed that ETV5 was regulated by miR-8067, and that ELK4 was a target for miR-4528. In a previous study, miR-4528 was revealed to be differentially expressed in colon cancer (31). Although the evidence for a critical role of miR-8067 and miR-4528 in GBM is minimal, they may aid the regulation of ELK4 and ETV5, and further investigation is required.

In the present study, the ceRNA analysis indicated that the ‘transcriptional misregulation in cancer’ pathway, which involves ELK4 and ETV5, was considerably dysregulated in GBM tumor samples. Therefore, ELK4 and ETV5 may be critical in tumor formation, and their expression levels were significantly associated with prognosis. ELK4 and ETV5 may be considered as prognostic markers for GBM, and the miRNAs regulating their expression may be candidate targets for GBM. In order to verify these assumptions, further investigations are required.

Despite its interesting findings, the present study had some limitations. Firstly, experimental verifications of the results using clinical specimens or cell lines have not been included due to insufficient material and funding. In addition, the sample size was not large enough to produce significant results. In conclusion, due to the analysis design and comprehensive bioinformatics analysis, the results obtained in the present study may be of great interest to identify novel prognostic markers for GBM. Further validation will be the focus of further studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Fengping Shan (Department of Immunology, China Medical University) for critical advice for the manuscript and Dr Wei Song (Bioinformatics Department, Eryun Information Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GBM

glioblastoma

- ceRNA

competing endogenous RNAs

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

HW and YT conceived and designed the experiments. HZ and JZ performed the statistical analyses. HW and JZ interpreted the data. HW, HZ and JZ drafted the manuscript. HW and YT revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Luhe Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University (Beijing, China), and all patients provided informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi Pier P. A ceRNA hypothesis: The rosetta stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tay Y, Kats L, Salmena L, Weiss D, Tan SM, Ala U, Karreth F, Poliseno L, Provero P, Di Cunto F, et al. Coding-independent regulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by competing endogenous mRNAs. Cell. 2011;147:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RM, Jamshidi A, Davis G, Sherman JH. Current trends in the surgical management and treatment of adult glioblastoma. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:121. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.05.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallego O. Nonsurgical treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Curr Oncol. 2015;22:e273–E281. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condon DM, Revelle W. The international cognitive ability resource: Development and initial validation of a public-domain measure. Intelligence. 2014;43:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2014.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parrish RS, Spencer HJ., III Effect of normalization on significance testing for oligonucleotide microarrays. J Biopharm Stat. 2004;14:575–589. doi: 10.1081/BIP-200025650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smyth GK. Limma: Linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Springer; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 397–420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Cao C, Ma Q, Zeng Q, Wang H, Cheng Z, Zhu G, Qi J, Ma H, Nian H, Wang Y. RNA-seq analyses of multiple meristems of soybean: Novel and alternative transcripts, evolutionary and functional implications. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao Q, Liu C, Yuan X, Kang S, Miao R, Xiao H, Zhao G, Luo H, Bu D, Zhao H, et al. Large-scale prediction of long non-coding RNA functions in a coding-non-coding gene co-expression network. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3864–3878. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeggari A, Marks DS, Larsson E. miRcode: A map of putative microRNA target sites in the long non-coding transcriptome. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2062–2063. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang JH, Li JH, Shao P, Zhou H, Chen YQ, Qu LH. starBase: A database for exploring microRNA-mRNA interaction maps from Argonaute CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res 39 (Database issue) 2011:D202–D209. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fromm B, Billipp T, Peck LE, Johansen M, Tarver JE, King BL, Newcomb JM, Sempere LF, Flatmark K, Hovig E, Peterson KJ. A uniform system for the annotation of vertebrate microRNA genes and the evolution of the human microRNAome. Annu Rev Genet. 2015;49:213–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao KM, Chen XC, Zhang JX, Wang Y, Yan W, You YP. A pseudogene-signature in glioma predicts survival. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:23. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0137-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos AR, Elong Edimo W, Erneux C. Phosphoinositide 5-phosphatase activities control cell motility in glioblastoma: Two phosphoinositides PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2 are involved. Adv Biol Regul. 2018;67:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Gillick JL, Neil J, Tobias M, Thwing ZE, Murali R. Distinct signaling mechanisms of mTORC1 and mTORC2 in glioblastoma multiforme: A tale of two complexes. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;57:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helgeson BE, Tomlins SA, Shah N, Laxman B, Cao Q, Prensner JR, Cao X, Singla N, Montie JE, Varambally S, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2:ETV5 and SLC45A3:ETV5 gene fusions in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:73–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monge M, Colas E, Doll A, Gonzalez M, Gil-Moreno A, Planaguma J, Quiles M, Arbos MA, Garcia A, Castellvi J, et al. ERM/ETV5 up-regulation plays a role during myometrial infiltration through matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6753–6759. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breunig JJ, Levy R, Antonuk CD, Molina J, Dutra-Clarke M, Park H, Akhtar AA, Kim GB, Town T, Hu X, et al. Ets factors regulate neural stem cell depletion and gliogenesis in ras pathway glioma. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3407. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Newbern JM, Wu Y, Morgan-Smith M, Zhong J, Charron J, Snider WD. MEK is a key regulator of gliogenesis in the developing brain. Neuron. 2012;75:1035–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seth A, Watson DK. ETS transcription factors and their emerging roles in human cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2462–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oikawa T. ETS transcription factors: Possible targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:626–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gasi Tandefelt D, Boormans J, Hermans K, Trapman J. ETS fusion genes in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:R143–R152. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaikhibrahim Z, Braun M, Nikolov P, Boehm D, Scheble V, Menon R, Fend F, Kristiansen G, Perner S, Wernert N. Rearrangement of the ETS genes ETV-1, ETV-4, ETV-5, and ELK-4 is a clonal event during prostate cancer progression. Human Pathol. 2012;43:1910–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickman DS, Pflueger D, Moss B, VanDoren VE, Chen CX, de la Taille A, Kuefer R, Tewari AK, Setlur SR, Demichelis F, Rubin MA. SLC45A3-ELK4 is a novel and frequent erythroblast transformation-specific fusion transcript in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2734–2748. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Day BW, Stringer BW, Spanevello MD, Charmsaz S, Jamieson PR, Ensbey KS, Carter JC, Cox JM, Ellis VJ, Brown CL, et al. ELK4 neutralization sensitizes glioblastoma to apoptosis through downregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:1202–1212. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang YN, Chen ZH, Chen WC. Novel circulating microRNAs expression profile in colon cancer. A pilot study Eur J Med Res. 2017;22(51) doi: 10.1186/s40001-017-0294-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.