Abstract

PURPOSE:

The prevalence and determinants of dry eye disease (DED) among 40 years and older population of Riyadh (except capital), Saudi Arabia.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS:

A population-based survey was conducted in Riyadh district between 2013 and 2017. All Saudi aged >40 years attended at the Primary Health Center were the study population. McCarty Symptom Questionnaire was adopted. A representative sample was examined. The best-corrected visual acuity and anterior and posterior segment assessment were performed. DED was graded as absent, mild, moderate, and severe.

RESULTS:

We examined 890 participants. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of DED was 45.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 44.8–45.4). One-third of the participants had DED. However, two-third of DED cases were of mild grade. The prevalence of DED among females was significantly higher. The variation of DED by age group was not statistically significant (χ2= 2.6, Degree of freedom = 3, and P = 0.1). Presence of glaucoma was significantly associated to DED (odds ratio [OR] = 2.6, [95% CI = 1.2–5.6], and P = 0.01). Use of topical glaucoma medication was significantly associated to DED (OR = 4.6 [95% CI = 1.8–11.8], and P = 0.001). However, severity of DED was not found to be associated with glaucoma medication (χ2= 2.6, P = 0.1). Associations of diabetes and hypertension to DED were not statistically significant (OR = 0.97 [95% CI = 0.73–1.3], and P = 0.84) (OR = 1.1 [95% CI = 0.8–1.4], and P = 0.6). The severe visual impairment was not associated to the grade of DED (P = 0.55).

CONCLUSION:

The prevalence of DED among Saudi is high, but severe DED is found to be less. Association with female gender, glaucoma, and topical glaucoma medications was reported. Association with diabetes, hypertension, and age group variation was not significant.

Keywords: Dry eye disease, McCarty symptom questionnaire, prevalence

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is a global health problem.[1] It was a common cause for ophthalmic visits in an eye hospital.[2] The prevalence of DED in the literature ranges from 7.4% to 33.7%.[3] Patients experience difficulties in daily activities that negatively affect vision-related quality of life.[4] Rapid industrialization, urbanization, and modernization will likely lead to increased DED in the developing countries.[5] It is a multifactorial disease having a number of different interacting causes or influences.[6] Diagnosis depends on symptoms and objective tests.[7] The symptoms of DED vary on geographic location, climatic conditions, and the lifestyle of the people.[8] Currently, there is no gold standard diagnostic test for DED.[9] Symptoms and objective tests, unfortunately, do not correlate well.[10] In developing nations with limited resources of diagnostic tests, questionnaires related to symptoms are used for the management of DED.

DED magnitude in studies varies in the Middle East from 8.7% in Iran to 32.1% in Saudi Arabia.[3,11] Age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, glaucoma, and topical medication are known risks factors for DED.[12,13,14] However, studies in the past have not shown conclusive association and special relationship of these factors to DED.[13,15]

In Riyadh Governorate, a prevalence study to focus on common and blinding eye diseases among 40 years and older population was held in Riyadh Governorate (except the capital), Saudi Arabia. One of the components of this survey was DED. Visual disabilities and confirmed blinding eye diseases were also detected and could, therefore, be associated with the DED. The exclusion of capital area was intentional because the urban residents have easy access to specialized health-care facilities and have more controlled environment compared to the rest of Riyadh Governorate where the desert area is with low humidity and high temperature and ophthalmic services are not easy to avail.

In this research paper, community-based prevalence of DED among 40 years and older population, its risk factors, and association with visual disabilities are presented.

Subjects and Methods

The Institutional Research Board approved this study (P-1309). The Ministry of Health, Riyadh Governorate, also approved and supported this survey. This study adhered to the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki. The survey was conducted between 2013 and 2017. Saudi residents aged 40 years and older residing in the study area were our study population. The study area was catchment area of all listed Primary Health Centers (PHCs) of Riyadh Governorate except those located in the Riyadh City. Saudi families registered with PHC and residing in the area were included for the present study. Randomly selected families and those age 40 years and above were invited to participate in the survey. Individuals who refused participation were excluded from the study. Verbal informed consent was obtained.

To calculate the sample size for the survey, we referred to the projection of population based on Census 2010. To select a representative sample of the 100,000 Saudi nationals in the Riyadh Governorate (except the capital), we assumed that the prevalence of DED in individual over 40-years old would be 32.1%.[3] To achieve 95% confidence interval (CI), 5% error margin, and 2% design effect, 670 individuals were required to be interviewed and examined. To compensate for loss of data, we increased the sample by 10%. Thus, the final sample size was at least 740 persons. OpenEpi software (Sullivan, Atlanta, GA, USA) was used to calculate the sample size.

There were 400 PHCs in this area and of them, seven PHCs were randomly selected. Each of 400 PHC had equal opportunity to be included in the survey. The family lists that were resident of the catchment area of the PHC was referred for randomly selecting families for including in the present survey. The patients visiting PHC were not included in the survey. The administrators of the PHC and a local coordinator assisted the survey team. The study team included one optometrist, one ophthalmologist, and one clinical coordinator. The optometrist gathered the demographic information (age, gender, and village name) and tested vision of the participants. A history obtained from all the participants included diabetes, glaucoma, use of glaucoma medication, hypertension, and past ocular morbidity or surgery. The dry eye symptoms were specifically inquired included ocular discomfort, foreign body sensation, itching in eye, tearing, dryness in eyes, and intolerance to bright light. The McCarty Symptom Questionnaire was adopted to collecting this information.[16,17] Based on the severity, each symptom as described by McCarty, was further graded as: absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), and severe (3).[16] The symptom score was summed for each eye. Among the two eyes of an individual, the eye which shows higher score of DED grading was taken to define DED status of that individual. The history of diabetes and hypertension was reconfirmed with the PHC patient chart. The questionnaire also included information about glaucoma medications, especially if they were used in the past 3 days and a history of glaucoma surgery in either eye.[18] The anterior segment assessment was carried out using slit-lamp biomicroscope (Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) to note conjunctival fold, corneal damage due to exsiccation, tear meniscus abnormalities, meibomian gland dysfunction, blink abnormalities, and lid-to-globe apposition. The Schirmer test, vital staining, and fluorescein break up time (BUT) were not included in this study to define DED.

Data were collected using a pretested data collection form and then transferred to the spreadsheet of an Excel®(Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS-25) (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis. For univariate analysis, we used parametric method. The population for both age and gender groups as per the 2010 census projection was used as denominator. Based on the population projections for the year 2014 as per census 2010 data and annual growth rate, the central region of the KSA Riyadh Governorate had 8 million population that include 4.6 million Saudi nationals. There were 3 million Saudi 40 years and older in Riyadh Governorate (excluding capital).[19] The crude rates were based on the examined sample. The possible DED cases in the subgroup (age group, gender, and seven clusters) were estimated and then in the study population to present age–sex-adjusted prevalence. The DED was associated to the demographic and other known risk factors by using odd's ratio (OR), the 95% CI, and two-sided P values. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

In this study, we examined 890 Saudi people of 40 years and older ages residing in seven villages. The distribution of the study population and the examined sample is compared in Table 1. Males and females in the age groups “50–59,” “60–69,” and “70+” were overrepresented in this study. Therefore, age–sex standardization of the prevalence of DED was carried out.

Table 1.

Comparison of population and examined participants of the survey

| Male |

Age group | Female |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population, n (%) | Examined, n (%) | (A−B)/A† | Population, n (%) | Examined, n (%) | (A−B)/A | |

| 19,870 (49.1) | 146 (29.6) | 0.40 | 40-49 | 19,041 (49.3) | 156 (39.4) | 0.20 |

| 11,088 (27.4) | 155 (31.4) | −0.14 | 50-59 | 10,446 (27.0) | 134 (33.8) | −0.25 |

| 5342 (13.2) | 106 (21.5) | −0.62 | 60-69 | 5165 (13.4) | 67 (16.9) | −0.27 |

| 4128 (10.2) | 87 (17.6) | −0.72 | 70+ | 3970 (10.3) | 39 (9.8) | 0.04 |

| 40,428 (100) | 494 (100) | Total | 38,622 (100) | 396 (100) | ||

†A-B/A: Comparison of proportion. Total participants: 890. Dry eye of all grades was present in 320 participants

DED was noted in 320 individuals among 890 examined samples. The age–sex-adjusted prevalence of DED among Saudis aged 40 years and older and residing in the Riyadh Governorate (except the capital) was 45.1% (95% CI: 44.8–45.4). The rates of DED in each subgroup are presented in Table 2. Females (57.8%) had a statistically significantly higher age-adjusted prevalence of DED than males (33%). The variation of DED by age group was not statistically significant (χ2= 2.6, Degree of freedom = 3, and P = 0.1).

Table 2.

Prevalence of dry eye disease in 40 years and older population of Riyadh Governorate (except capital), Saudi Arabia

| Variable | Examined | DES | Crude (%) | Projected | Adjusted rate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 890 | 320 | 35.9 | 35,661 | 45.1 | 44.8-45.4 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 494 | 176 | 35.4 | 12,353 | 33.0 | 32.2-33.8 |

| Female | 396 | 144 | 36.4 | 22,308 | 57.8 | 57.2-58.4 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 40-49 | 302 | 100 | 33.1 | 18,001 | 46.3 | 45.6-47.0 |

| 50-59 | 289 | 106 | 36.7 | 11,654 | 54.1 | 53.2-55.0 |

| 60-69 | 173 | 62 | 35.8 | 3799 | 36.2 | 34.7-37.7 |

| 70 plus | 126 | 52 | 41.3 | 2207 | 27.3 | 25.4-29.2 |

| Cluster | ||||||

| Dariyah | 56 | 25 | 44.6 | 3776 | 48.9 | 47.3-50.5 |

| Dhrumah | 162 | 60 | 30.0 | 879 | 36.4 | 33.2-39.6 |

| Horaimila | 139 | 21 | 15.1 | 214 | 14.8 | 10.0-19.6 |

| Karj | 76 | 29 | 38.2 | 20,316 | 45.9 | 45.2-46.6 |

| Majmah | 167 | 88 | 52.7 | 7940 | 50.4 | 49.3-51.5 |

| Muzamiah | 192 | 66 | 33.3 | 1396 | 34.4 | 31.9-36.9 |

| Rumah | 98 | 33 | 33.7 | 1140 | 34.1 | 31.3-36.9 |

CI: Confidence interval, DES: Dry eye syndrome

Of the 240 females aged 50 years and older, 151 were with DED. There could be as many as 12,000 menopausal females suffering from DED in the study area. The prevalence thus in this gender and age group would be 61.3% (95% CI: 60.6–62.0).

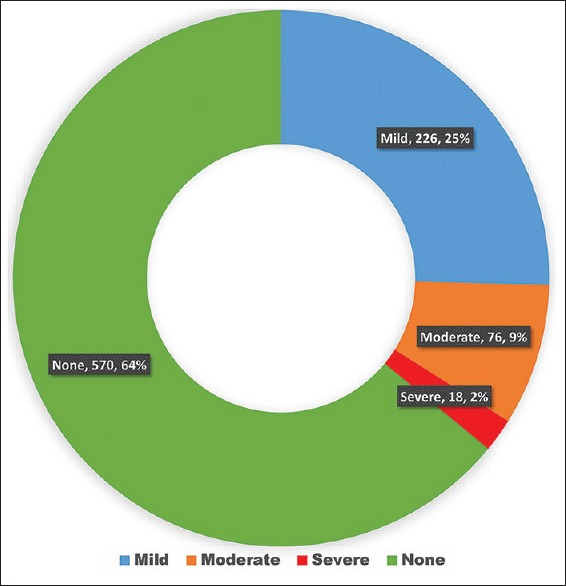

The proportion of different grades of DED is given in Figure 1. Thirty-five percent of the participants had DED of which, two-thirds had mild DED.

Figure 1.

Proportion of different grades of dry eye disease in 40 years and older population of Riyadh Governorate (except capital), Saudi Arabia

The presence of glaucoma was associated to DED (OR = 2.6, [95% CI: 1.2–5.6], and P = 0.01). The age–sex-adjusted prevalence of glaucoma in the study population was 5.59% (95% CI: 5.43–5.75). Use of topical glaucoma medication was significantly associated to DED (OR = 4.6, [95% CI: 1.8–11.8], and P = 0.001). Among all glaucoma case, 86.2% were using topical medication. The severity of DED was not associated with glaucoma medication (χ2= 2.6 and P = 0.1). DED was not statistically significantly associated to diabetes and hypertension (OR = 0.97, [95% CI: 0.73–1.3], and P = 0.84) (OR = 1.1 [95% CI: 0.8–1.4], and P = 0.6).

The visual disabilities and grade of DES are given in Table 3. The severe visual impairment (SVI) was not associated to the grade of DED (P = 0.55).

Table 3.

Visual impairment and dry eye disease among Saudi population aged 40 years and older in Riyadh Governorate (except capital), Saudi Arabia

| Grade of dry eye disease | Severe visual impairment (n=54) | Mild/moderate visual impairment (n=836) | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| No DES | 16 (29.6) | 247 (29.5) |

χ2=0.3 df=0 3 P=0.55 |

| Mild | 30 (55.6) | 507 (60.7) | |

| Moderate | 6 (11.1) | 67 (8.0) | |

| Severe | 2 (3.7) | 15 (1.8) |

df: Degree of freedom, DES: Dry eye syndrome

Discussion

The outcome of the current study indicates that 35% of Saudis aged 40 years and older residing in the Riyadh Governorate (except the capital) had DED. One in 16 individuals had severe DED. Females of menopausal age, glaucoma patients, and those using glaucoma medications had a higher prevalence of DED. The severity of DED was not associated to the status of visual disability in the Saudi population aged 40 years and older.

To our knowledge, this is the first publication correlating the grades of DED to the visual disability in the central area of Saudi Arabia. This information can be used to improve eye care not only in the study area but also in other areas with a similar climate and environmental conditions.

DED in our study area seems to be high compared to the rates noted in India and Iran.[1,11] Surprisingly, the prevalence in our study was much lower than 93.1% noted through a hospital-based study in Jeddah (a coastal town) a Western Region of Saudi Arabia.[15] However, in Al-Ahsa (60 Km away from seashore), an Eastern Region of the kingdom, had 32.1% prevalence of DED.[3] Environmental factors such as sun exposure, dust, and wind exacerbate or precipitate DED.[20] These factors are common in all these three study sites.[3,15] However, our study area has very low humidity throughout the year. This poses a higher risk of DED and it is likely to persist in coming years.[21] With increasing life spans of nationals in countries with rapidly developing economies, the burden of DED and the cost of care are likely to increase.[22] Therefore, a periodic magnitude of DED although not causing SVI need to be generated for planning eye care. While comparing our study results, it is essential to note difference in climate, age groups of the target population, and location of the study area.

The magnitude of DED among older population is although high it is of milder nature to a large extent. However, it should be reviewed in context of increasing life expectancy of Saudis population, low humidity in the study area, and wider usage of gadgets such as smartphones, computers, and visual display terminals. In addition, air-conditioned offices, air-conditioned cars, airplane cabins, and extreme hot or cold weather which the study population experiences will have a negative impact on their tear film.[20]

DED prevalence was higher in females in our study. A higher preponderance of DED among females was also reported in studies from Jeddah, Al-Ahsa of Saudi Arabia and India.[3,15,23] The higher prevalence of DED among females is unusual because in Saudi Arabia, males remain outdoors for a longer time compared to the females who have limited outdoor mobility, especially in semi-urban areas. This unusual high DED in female could be explained by more time spent in an air-conditioned environment and more use of computer and smartphone. An alternative explanation could be female hormone noted as a risk factor for DED.[24] Titiyal et al. reported that males had higher DED rates than females.[1] The higher prevalence DED among males could be due to barriers females face for accessing health services in developing countries such as India.[25] Gender and its association to DED warrants further studies.

We assumed that females above 50 years of age among Arab population are suffering from menopause.[26] The rate in this vulnerable group was significantly higher than the rate in general adult population. It should be noted that female hormone levels were not assessed in our study, but such association of menopause in women to DED was confirmed and subsequent hormonal therapy improved DED.[27]

Age was not associated to DED among 40 years and older population in our study. Titiyal et al.[1] also did not find a significant difference in DED among patients, 40 years and older. In contrast, Shah and Jani[23] found that age was positively associated with DED. With increasing age, some of the functions of the lacrimal gland and drainage system are likely to deteriorate. Variation of age as risk factor to DED in different studies should be linked with caution as methods, target population, and different study sites.

There was no association of DED with diabetes and hypertension in our study. Titiyal et al.[1] also did not find an association of DED to diabetes or hypertension. This is in contrast with other studies.[3] High prevalence of DED, hypertension, and diabetes in older Saudi population could have resulted in nonsignificant association between these factors. A longitudinal study is recommended to confirm this finding.

Glaucoma was significantly associated to DED in the present study. Erb et al.[18] also noted similar association and proposed that autonomous nervous system dysfunction (intraocular eye pressure, ocular perfusion, and tear production are subject to neuronal control) resulted in reduced basal tear production.

DED was positively associated to the history of glaucoma medications usage in our study. Drug-induced disturbances on the ocular surface and tear film can lead to dry eye. Corneal and conjunctival sensitivity which are responsible for reflex tear secretion and viability of tear film was reported low in patients using topical hypotensive medications for a long time.[28]

Although we noted association of DED to glaucoma medication, we could not establish a dose–response relationship. The severity of DED was not associated with the use of glaucoma medication in our study. Perhaps, comprehensive baseline data on DED status prior to the start of glaucoma medication and at different follow-up will benefit glaucoma patients.

We did not find significant association of DED to the visual impairment grade. Low rate of SVI and high rate of mild DED in the present study could have resulted in such spurious nonassociation.

There are few limitations to our study: (1) This being a cross-sectional study, the special relationship of DED to risk factors found could not be established and further longitudinal studies are recommended. (2) Our study was part of a major survey on visual disabilities and blinding eye diseases. Therefore, some known risk factors such as smoking, contact lens use, time spend under air condition, and computer uses were not evaluated. (3) We did not inquire about type of glaucoma medication and preservatives added eye medication with benzalkonium chloride as preservative has been found to further aggravate DED.[18] (4) DED was based on client perceived symptoms score and not on the objective measures to define DED. Therefore, we recommend caution when comparing the outcomes of the current study to studies using objective parameters such as tear film BUT and inflammatory markers. (5) The survey was in semi-urban area adjoining a large city, Riyadh. The later has excellent health services both in the government and private sectors. Therefore, extrapolation of study outcomes to other regions with urban and rural mix population should be done with caution. Since the field part of the study was done in 1 year that included both summer and winter season (with temperature in day time ranging from 25°C to 50°C), we could not establish association of DED to season.

Conclusion

The prevalence of DED among Saudi adults aged 40 years or older was 35%. However, a large proportion of them had mild DED. It was significantly associated to female gender, presence of glaucoma, and use of topical glaucoma medications. Diabetes, age group, and hypertension were not significantly associated to DED.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Titiyal JS, Falera RC, Kaur M, Sharma V, Sharma N. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease in North India: Ocular surface disease index-based cross-sectional hospital study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:207–11. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_698_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amparo F, Dana R. Web-based longitudinal remote assessment of dry eye symptoms. Ocul Surf. 2018;16:249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alshamrani AA, Almousa AS, Almulhim AA, Alafaleq AA, Alosaimi MB, Alqahtani AM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye symptoms in a Saudi Arabian population. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2017;24:67. doi: 10.4103/meajo.MEAJO_281_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benítez-Del-Castillo J, Labetoulle M, Baudouin C, Rolando M, Akova YA, Aragona P, et al. Visual acuity and quality of life in dry eye disease: Proceedings of the OCEAN group meeting. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:169–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osae AE, Gehlsen U, Horstmann J, Siebelmann S, Stern ME, Kumah DB, et al. Epidemiology of dry eye disease in Africa: The sparse information, gaps and opportunities. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, Djalilian A, Dogru M, Dumbleton K, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:539–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janine AS. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: Report of the epidemiological subcommittee of the international dry eye workshop. Ocul Surf. 2007;5:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amparo F, Schaumberg DA, Dana R. Comparison of two questionnaires for dry eye symptom assessment: The ocular surface disease index and the symptom assessment in dry eye. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidl D, Witkowska KJ, Kaya S, Baar C, Faatz H, Nepp J, et al. The association between subjective and objective parameters for the assessment of dry-eye syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:1467–72. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Kheirkhah A, Emamian MH, Mehravaran S, Shariati M, et al. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome in an adult population. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42:242–8. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchino M, Nishiwaki Y, Michikawa T, Shirakawa K, Kuwahara E, Yamada M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease in Japan: Koumi study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Houssien AO, Al Houssien RO, Al-Hawass A. Magnitude of diabetes and hypertension among patients with dry eye syndrome at a tertiary hospital of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia – A case series. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2017;31:91–4. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi GC, Tinelli C, Pasinetti GM, Milano G, Bianchi PE. Dry eye syndrome-related quality of life in glaucoma patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:572–9. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bukhari A, Ajlan R, Alsaggaf H. Prevalence of dry eye in the normal population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Orbit. 2009;28:392–7. doi: 10.3109/01676830903074095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarty CA. McCarty Symptom Questionnaire. Australia, Melbourne: University of Melbourne, Department of Ophthalmology; 1998. [Last updated on 2004 Oct 22; Last accessed on 2018 Aug 01]. Available from: http://www.tearfilm.org/dewsreport/pdfs/Questionnaire%20McCarty%20Symptom%20Questionnaire%20(Caffery).pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarty CA, Bansal AK, Livingston PM, Stanislavsky YL, Taylor HR. The epidemiology of dry eye in Melbourne, Australia. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1114–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erb C, Gast U, Schremmer D. German register for glaucoma patients with dry eye. I. Basic outcome with respect to dry eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1593–601. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0881-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health, Statistical Book. [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/Statistical-Yearbook-1437H.pdf .

- 20.Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:405–12. doi: 10.2147/opth.s5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elachola H, Memish ZA. Oil prices, climate change – Health challenges in Saudi Arabia. Lancet. 2016;387:827–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00203-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald M, Patel DA, Keith MS, Snedecor SJ. Economic and humanistic burden of dry eye disease in Europe, North America, and Asia: A systematic literature review. Ocul Surf. 2016;14:144–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah S, Jani H. Prevalence and associated factors of dry eye: Our experience in patients above 40 years of age at a tertiary care center. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2015;8:151–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.169910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vehof J, Sillevis Smitt-Kamminga N, Nibourg SA, Hammond CJ. Sex differences in clinical characteristics of dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2018;16:242–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baru R, Acharya A, Acharya S, Kumar AS, Nagaraj K. Inequities in access to health services in India: Caste, class and region. Economic and Political Weekly. 2010;45:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizk DE, Bener A, Ezimokhai M, Hassan MY, Micallef R. The age and symptomatology of natural menopause among United Arab Emirates Women. Maturitas. 1998;29:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sriprasert I, Warren DW, Mircheff AK, Stanczyk FZ. Dry eye in postmenopausal women: A hormonal disorder. Menopause. 2016;23:343–51. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero-Díaz de León L, Morales-León JE, Ledesma-Gil J, Navas A. Conjunctival and corneal sensitivity in patients under topical antiglaucoma treatment. Int Ophthalmol. 2016;36:299–303. doi: 10.1007/s10792-015-0115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]