Abstract

Cancer stem cell (CSC) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are associated with treatment resistance and outcomes of patients with cancer. The present study investigated the prognostic implications of pre-therapeutic expression of ABC transporters and CSC markers in patients with colon cancer (CC) who received adjuvant 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin combination therapy (FOLFOX-4). The immunohistochemical expression of 3 ABC transporters, including ABC subfamily C member 2 (ABCC2), ABCC3 and ABC subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2), and 3 CSC markers, including sex determining region Y-box 2 (SOX2), leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1, were determined in 164 CC tissues from patients with stage III CC, who underwent postoperative FOLFOX-4 chemotherapy. The association between the protein expression and patients' prognoses was statistically analyzed. ABCG2 was associated with favorable overall survival rate (OS; P=0.001), and ABCC2, ABCG2 and SOX2 were associated with increased disease-free survival rate (DFS; P=0.001, 0.002 and 0.013, respectively). In multivariate analyses, ABCG2 was an independent prognostic factor for OS [hazard ratio (HR)=2.877; P=0.046], and ABCC2 and SOX2 were independent prognostic factors for DFS (HR=2.831; P=0.014; HR=2.558, P=0.020, respectively). ABCC2, ABCG2 and SOX2 may be promising prognostic markers for patients with CC receiving FOLFOX-4 therapy.

Keywords: colon cancer, ATP-binding cassette transporter, cancer stem cell, adjuvant chemotherapy, prognosis

Introduction

Colon cancer (CC) is one of the most common malignancy types of the gastrointestinal tract and a leading cause of cancer-associated mortalities worldwide in 2012 (1). Over the last decade, postoperative chemotherapy has become the standard treatment for locally advanced CCs, administered to avoid recurrences of cancer following surgery, and has notably improved the prognostic outcomes of patients with CC (2–6). In particular, adjuvant 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and oxaliplatin combination therapy, termed FOLFOX, is a widely accepted standard regimen for resected stage III CC (7). However, therapeutic responses and clinical outcomes differ among individual patients.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a small population of cancer cells that share common properties with normal stem cells, including the ability of self-renewal and multi-directional differentiation (8,9). Due to these properties, subsequent to undergoing radio- or chemotherapy, the residual CSCs can rapidly proliferate to re-establish the tumor (10). Additionally, CSCs have variable intrinsic or acquired drug resistance mechanisms, including hypoxic stability, enhanced activity of repair enzymes and expression of antiapoptotic proteins, including B-cell lymphoma 2 (10–12). Therefore, the presence of CSCs has been considered to be a major contributor to the development of chemoresistance in malignant tumor cases (13–15). Expression of drug efflux transporters is also associated with the chemoresistant properties of CSCs (14,16–18). ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter proteins serve as efflux pumps to actively extrude molecules out of cells, and expression of ABC transporters in cancer cells is one of the major causes of multidrug resistance, a key obstacle to cancer chemotherapy (19). Multiple transporters, including ABC subfamily B member 1 and ABC subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2), have been identified in CSCs and have been indicated to serve an important role in the clinical resistance of CSCs to anticancer drugs (17,18).

The prognostic importance of the transcript or protein expression level of CSC markers and ABC transporter has been reported in colorectal cancer (20–23), and also investigated in colorectal cancer cohorts treated with specific adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment (24–27). Furthermore, the association between ABC transporters or CSC properties and chemoresponses has been reported using multiple colorectal cancer cell lines (28–30). Overexpression of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) reduced the sensitivity toward 5-FU and oxaliplatin of Lovo, HT29 and HCT116 cells (29), and inhibition of ABC subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) increased sensitivity to 5-FU (30) in HT29 and SW480 cells. Expression of ABC transporters in colorectal cancer tissues has been associated with chemoresponse. Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with immunohistochemical (IHC) overexpression of ABCG2 indicated resistance to 5-FU-based treatment (31), and aberrant ABCC3 protein expression had been reported to be associated with chemo-radioresistance in patients with rectal cancer (30). Despite the aforementioned results, Hlavata et al (24) reported that transcript levels of various ABC transporters, including ABC subfamily C member 6, ABC subfamily C member 11, ABC subfamily F member 1 and ABC subfamily F member 2, were decreased in non-responders to palliative chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer.

The present study evaluated the expression of multiple ABC transporters and CSC markers in cancer tissues from a homogeneous group of patients with stage III CC postoperatively receiving 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin combination therapy (FOLFOX-4 regimen) using an IHC method and statistically analyzed their prognostic significance. Through the literature review, 3 ABC transporters, including ABCC2, ABCC3 and ABCG2, and 3 CSC markers, including LGR5, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) and sex determining region Y-box 2 (SOX2) were selected, of which primary antibodies for IHC staining were available and clinical implications have been reported in patients with colorectal cancer (21,22,24,26,27,30–34). The results of the present study will provide fundamental data for investigating the usefulness of ABC transporters and CSC markers as prognostic markers and as target molecules.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

A total of 164 CC tissues were collected for the present study from patients with stage III CC who had received postoperative adjuvant therapy with the FOLFOX-4 regimen between May 2003 and December 2010 at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (Seongnam, South Korea). The mean age of the patients at diagnosis was 59.8±10.4 years. A total of 58 patients (35.4%) were female and 106 (64.6%) were male (Table I). Therapeutic and prognostic data were collected from the archives of the Department of Internal Medicine of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: the presence of histologically proven adenocarcinomas of primary CCs, the availability of paraffin blocks of the resected specimens and available information on the follow-up conducted on these patients. Histopathological and clinical data were obtained from the medical records and pathological reports of the patients. Pathological stage was determined per the grading system of the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (35). Patients did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and were followed-up through November 1 2015. Follow-up of patients was scheduled at 3-monthly intervals for up to 2 years, 6-monthly intervals for up to 5 years, and annually thereafter. During follow-up visits, all relevant data were collected. All tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin at 24°C for 12 h and embedded in paraffin. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Research Using Human Subjects at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB no. B1512-326/302).

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with CC.

| Variables | Value, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (range) | 59.8±10.4 (28–80) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 58 (35.4) |

| Male | 106 (64.6) |

| Location (%) | |

| Right colon | 50 (30.5) |

| Left colon | 114 (66.5) |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (range) | 5.1±1.9 (1.5–11.0) |

| Gross type (%) | |

| Polypoid | 8 (4.9) |

| Ulcerofungating | 91 (55.8) |

| Ulceroinfiltrative | 63 (38.7) |

| Flat (%) | 1 (0.6) |

| Microsatellite instability statusa | |

| Microsatellite instability-high | 8 (4.8) |

| Microsatellite instability-low | 9 (5.5) |

| Microsatellite stable | 146 (89.6) |

| Differentiation (%) | |

| Well differentiated | 3 (1.9) |

| Moderately differentiated | 139 (88.0) |

| Poorly differentiated | 16 (10.1) |

| Pathological T stage (%)a | |

| pTis | 0 (0) |

| pT1 | 2 (1.2) |

| pT2 | 4 (2.4) |

| pT3 | 124 (75.6) |

| pT4a | 29 (17.7) |

| pT4b | 5 (3.0) |

| Pathological N stage (%)a | |

| N0 | 0 (0) |

| N1 | 102 (62.6) |

| N2 | 62 (37.3) |

| Lymphatic invasion (%) | |

| Present | 88 (53.7) |

| Not identified | 76 (46.3) |

| Vascular invasion (%) | |

| Present | 29 (17.7) |

| Not identified | 135 (82.3) |

| Perineural invasion (%) | |

| Present | 68 (41.5) |

| Not identified | 96 (58.5) |

| Disease progression | 29 (17.7) |

| Local recurrence only | 4 (2.4) |

| Distant metastasis only | 23 (14.0) |

| Local recurrence and distant metastasis | 2 (1.2) |

| No recurrence/metastasis | 135 (82.3) |

| Death | 16 (9.8) |

Pathological T and N stage were determined according to the Grading System of the 8th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (35). T, tumor; N, node; CC, colon cancer.

Chemotherapeutic treatment

A total of 12 cycles of the adjuvant FOLFOX-4 regimen were administered. Each cycle consisted of a 2-h infusion of oxaliplatin at a dose of 85 mg/m2 administered simultaneously with a 2-h infusion of leucovorin at a dose of 200 mg/m2, followed by a bolus of 5-FU at a dose of 400 mg/m2, and then a 22-h infusion of 5-FU at a dose of 600 mg/m2 administered on 2 consecutive days. This cycle was repeated every 2 weeks. Detailed frequencies of adverse events were presented in Table SI. The grade for adverse event was determined according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v. 4.0 (36). Dosage of chemotherapy was determined every cycle by each physician's discretion. The physicians were affiliated with Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. Relative dose intensities of oxaliplatin and 5-FU were not different according to protein expression (data not shown).

Construction of tissue microarrays (TMAs)

A representative tumor section slide and the corresponding paraffin block (donor block) were collected from each case following slide review. Following the marking of areas of high tumor cell density on the selected slides, tumor cores (2 mm diameter) were obtained from the corresponding areas of the paraffin blocks, using a trephine apparatus. A total of 164 trephined paraffin tissue cores from 164 patients were consecutively placed into recipient blocks (TMA blocks). Each TMA block incorporated up to 60 samples.

IHC staining and interpretation of results

Detailed information regarding used primary antibodies is presented in Table II. IHC staining was performed using a BenchMark XT automated immunostaining system (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, 4-µm-thick sections were cut from each of the paraffin tissue blocks, mounted on positively charged slides, and dried at 62°C for 30 min. Subsequent to undergoing heat epitope retrieval at 98°C for 60 min in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (pH 8.0) in the autostainer, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersing the slides in a 3% hydrogen peroxidase solution for 4 min at 36°C. The samples were incubated with individual primary antibodies at 36°C for 32 min and then incubated with a mixture of horseradish peroxidase-labeled antibodies composed of goat anti-rabbit antibody and goat anti-mouse antibody included in the UltraView Universal DAB kit (cat. no. 760-500; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.) for 8 min at 36°C. Following treatment with 0.04% hydrogen peroxide in a phosphate buffer solution and DAB chromogen containing 0.2% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride at 36°C for 8 min, samples were treated with copper sulfate (5 µg/l) at 36°C for 4 min (all reagents used in these processes were included in the UltraView Universal DAB kit; cat. no. 760-500; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.). Slides were counterstained with 0.5% Modified Mayer's Hematoxylin at 36°C for 4 min. Placenta tissues were mounted on each slide as a positive control for LGR5, ABCC3 and ABCG2, and hepatic tissues were mounted as a positive control for ALDH1, SOX2 and ABCC2.

Table II.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemical staining.

| Antibody | Company | Cat. no. | Clonality | Reactivity | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC2 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | Ab3373 | Mouse monoclonal | Human | 1:50 |

| ABCC3 | Abcam | Ab3375 | Mouse monoclonal | Human | 1:20 |

| ABCG2 | Alexis Biochemicals; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA | ALX 801-029-C125 | Mouse monoclonal | Human | 1:200 |

| LGR5 | Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, | HPA012530 | Rabbit polyclonal | Human | 1:100 |

| ALDH1 | BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA | 44/ALDH | Mouse monoclonal | Human | 1:100 |

| SOX2 | EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA | 636675 | Mouse monoclonal | Human | 1:500 |

ABCC2, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 2; ABCC3, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2; LGR5, leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5; SOX2, sex determining region Y-box 2; ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

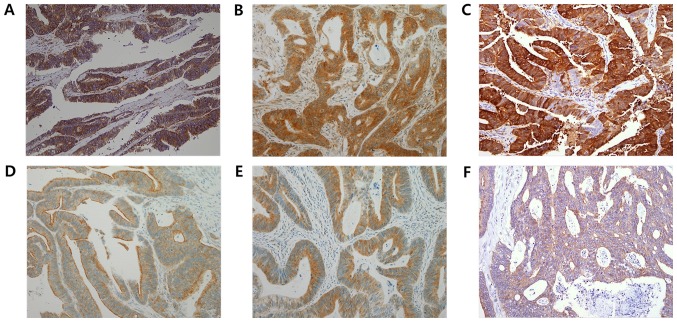

A total of two pathologists (ES and MLK) manually evaluated the IHC stained slides at ×200 magnification in a blinded fashion under a light microscope. Staining intensities were semi-quantitatively scored as negative (score=0), weak (score=1), moderate (score=2) or strong (score=3). Additionally, the percentage of immune-reactive cells was assessed. There are no established absolute criteria for immune-positivity for the examined proteins; therefore, by testing a series of different values, the staining results were deemed positive when >10% of tumor cells had intensity scores of ≥1. The representative immunostainings are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Representative immunohistochemical images of cancer stem cell markers and ABC transporters in colon cancer. (A) ABCC2, (B) ABCC3, (C) ABCG2, (D) LGR5, (E) SOX2 and (F) ALDH1 (magnification, ×200). ABCC2, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 2; ABCC3, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2; LGR5, leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5; SOX2, sex determining region Y-box 2; ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 21.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Spearman's Rho coefficient test was used to analyze correlations between expression levels of proteins. The associations between the status of expression of the different proteins and the clinicopathological features of the corresponding patients were analyzed using Pearson's χ2 test. For analysis of survival data, the differences between survival rates were determined using the log-rank test, and multivariate analysis was performed using the backward conditional method of Cox proportional hazards regression modeling. Disease-free survival rate (DFS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of first recurrence or mortality. Overall survival rate (OS) was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to the date the patient succumbed. Continuous variables are presented as the means ± standard deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of patients

The clinicopathological characteristics of patients with CC receiving adjuvant FOLFOX-4 treatment are detailed in Table I. By location, 30.5% of the tumors were localized in the right colon and 66.5% in the left colon. In 2 patients (1.2%), the CCs were classified as pathological stage T1, in 4 (2.4%) as stage T2, in 124 (75.6%) as stage T3, in 29 (17.7%) as stage T4a and in 5 (3.0%) as stage T4b. All cases exhibited lymph node metastases; 102 (62.6%) cases were classified as N1 and 62 (37.3%) cases were classified as N2 (Table I). Lymphatic, vascular and perineural invasion were indicated in 88 (53.7%), 29 (17.7%) and 68 (41.5%) patients, respectively. During follow-up, 29 patients had local recurrences or distant metastases, and 16 patients succumbed (Table I).

Expression profiles of ABC transporters and CSC markers

The expression frequencies of the examined ABC transporters were as follows: 87.1 (142/163) for ABCC2, 44.8 (73/164) for ABCC3 and 85.4% (140/164) for ABCG2. The expression frequencies of the CSC markers were 79.9 (131/164), 38.4 (63/164) and 82.3% (135/164) for LGR5, ALDH1 and SOX2, respectively. Immune-positivities with detailed case distribution according to intensity score are presented in Table III. Among the immune-positive cases, moderate intensity (intensity score 2) was the most frequent expression pattern for ABCC2, ABCC3 and LGFR5, while strong intensity was the most frequent expression pattern for ALDH1, ABCG2 and SOX2 immunostaining. Particularly, the expression intensity of ALDH1 was relatively strong with only one case exhibiting weak expression. Expression of ABCC2 was significantly associated with that of ABCC3 and LGR5 (Spearman's Rho coefficient =0.347 and 0.354, respectively; P<0.001). Additionally, there was an association between the expression of ABCC3 and SOX2 (Spearman's Rho coefficient =0.192; P=0.014) (data not shown).

Table III.

Expression frequencies of ABC transporters and stem cell markers.

| n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein classification | Protein | Intensity score 1 | Intensity score 2 | Intensity score 3 | Immune-positivity |

| ABC transporter | ABCC2 | 27/163 (16.6) | 71/163 (43.6) | 44/163 (27.0) | 142/163 (87.1) |

| ABCC3 | 13/164 (7.9) | 38/164 (23.2) | 22/164 (13.4) | 73/164 (44.5) | |

| ABCG2 | 39/164 (23.8) | 49/164 (29.9) | 52/164 (31.7) | 140/164 (85.4) | |

| Stem cell marker | LGR5 | 23/164 (14.0) | 62/164 (37.8) | 46/164 (28.0) | 131/164 (79.9) |

| ALDH1 | 1/164 (0.6) | 20/164 (12.2) | 42/164 (25.6) | 63/164 (38.4) | |

| SOX2 | 23/164 (14.0) | 52/164 (31.7) | 60/164 (36.6) | 135/164 (82.3) | |

ABCC2, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 2; ABCC3, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2; LGR5, leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5; sex determining region Y-box 2; ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

The association between the expression of ABC transporters and CSC markers and the clinicopathological parameters of the corresponding patients was tested using Pearson's χ2 test. Expression of ALDH1 was significantly associated with the right-sided location of tumors (P=0.010). However, no statistically significant associations were observed between expression of these proteins and the rest of the parameters (data not shown).

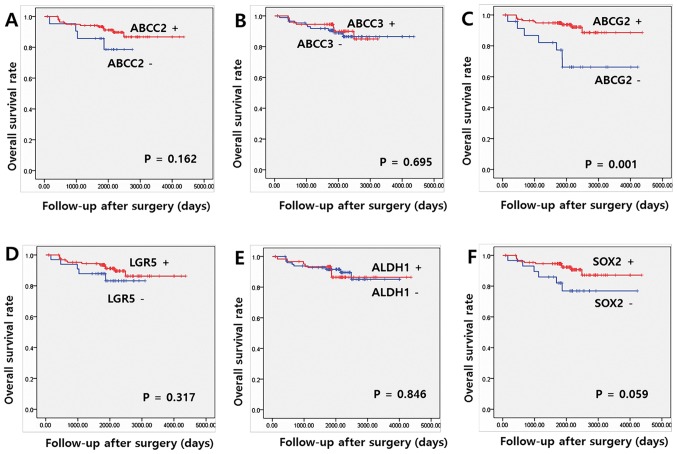

Association between the expression of ABC transporters and CSC markers and OS

The median and mean OS at the last follow-up appointment were 66.8 and 67.0 months, respectively. Univariate analysis indicated that ABCG2 expression was significantly associated with OS (P=0.001). Expression levels of other proteins, including ABCC2, ABCC3, LGR5, ALDH1 and SOX2, indicated no significant association with OS (Fig. 2). Among the clinicopathological parameters, pathological N stage, lymphatic invasion and perineural invasion exhibited an association with OS (P=0.040, 0.003 and 0.003, respectively; data not shown). Multivariate Cox regression analyses identified ABCG2 overexpression as an independent positive prognostic indicator of OS [hazard ratio (HR)=2.877 and 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.019–8.119; P=0.046). Lymphatic invasion also had a significant effect on OS in multivariate analysis (P=0.049; Table IV).

Figure 2.

Association between overall survival rate, and expression of cancer stem cell markers and ABC transporters. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve for patients with colon cancer according to (A) ABCC2, (B) ABCC3, (C) ABCG2, (D) LGR5, (E) ALDH1 and (F) SOX2. ABCC2, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 2; ABCC3, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2; LGR5, leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5; SOX2, sex determining region Y-box 2; ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

Table IV.

Multivariate analyses for overall survival rate in patients with colon cancer.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node stage | 0.584 | ||

| pN1 | 1 | ||

| pN2 | 1.353 | 0.458–3.997 | |

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.049a | ||

| Absent | 1 | ||

| Present | 4.718 | 1.006–22.124 | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.070 | ||

| Absent | 1 | ||

| Present | 2.962 | 0.915–9.588 | |

| ABCG2 | 0.046a | ||

| Negative | 2.877 | 1.019–8.119 | |

| Positive | 1 |

P<0.05. ABCG2, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

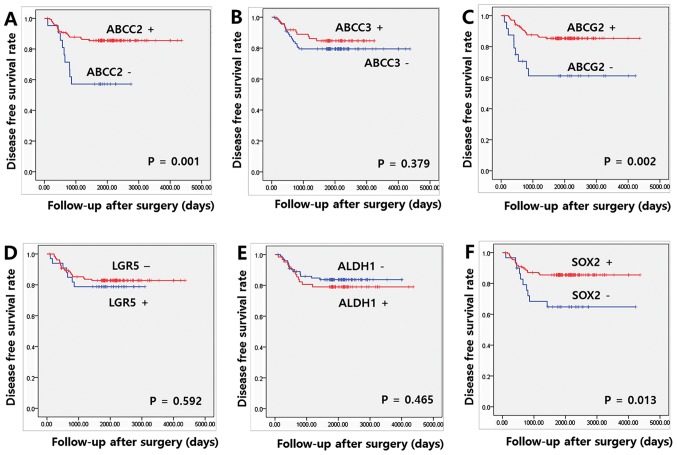

Association between the expression of ABC transporters and CSC markers and DFS

The median and mean DFS at the last follow-up appointment were 61.9 and 61.7, respectively. Significant increases in DFS were observed in patients who were positive for ABCC2, ABCG2 and SOX2, compared with patients who were negative for these proteins (P=0.001, 0.002 and 0.013, respectively; Fig. 3). Among the clinicopathological parameters, only the presence of perineural invasion was associated with a reduced DFS (P=0.013; data not shown). On multivariate Cox regression analyses for DFS, expression of ABCC2 and SOX2 remained independent prognostic factors of the FOLFOX group (HR=2.831, 95% CI=1.238–6.474 and P=0.014; and HR=2.558, 95% CI=1.156–5.658 and P=0.020, respectively; Table V).

Figure 3.

Association between disease-free survival rate and expression of cancer stem cell markers and ABC transporters. Kaplan-Meier disease free survival curve for patients with colon cancer according to (A) ABCC2, (B) ABCC3, (C) ABCG2, (D) LGR5, (E) ALDH1 and (F) SOX2. ABCC2, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 2; ABCC3, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2; LGR5, leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5; SOX2, sex determining region Y-box 2; ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

Table V.

Multivariate analyses for disease-free survival rate in patients with colon cancer.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perineural invasion | 0.023a | ||

| Absent | 1 | ||

| Present | 2.465 | 1.129–5.380 | |

| ABCC2 | 0.014a | ||

| Negative | 2.831 | 1.238–6.474 | |

| Positive | 1 | ||

| ABCG2 | 0.063 | ||

| Negative | 2.192 | 0.958–5.016 | |

| Positive | 1 | ||

| SOX2 | 0.020a | ||

| Negative | 2.558 | 1.156–5.658 | |

| Positive | 1 |

P<0.05. SOX2, sex determining region Y-box 2; ABCC2, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 2; ABCG2, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 2; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

CSCs and ABC transporters have been proposed as relevant prognostic biomarkers for outcomes and response to chemotherapy (20–23). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the potential use of CSC markers and ABC transporters as prognostic biomarkers in patients with stage III CC who had received the same adjuvant treatment, FOLFOX-4. It was indicated that ABCC2, ABCG2 and SOX2 were independent favorable prognostic markers in this CC cohort.

LGR5, expressed in the crypt base of the small and large intestines, has received attention as a marker for normal colon stem cells and colon CSCs (37). ALDH1, one of the common CSC markers, has been indicated to endow tumor cells with chemoresistance, due to its strong cellular detoxification activity (38,39). A number of studies reported an association between the expression of LGR5 or ALDH1 and patients' prognoses in various malignant tumor types, including breast cancer and gastric cancer (32,40). In patients with CC, an association between the expression of these proteins in the tumor and an unfavorable prognosis has been reported (21,22,27,33) and a number of studies reported the same association in a CC cohort treated with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemo- or chemoradiation treatment (26,27,41,42). However, conflicting results have also been reported in malignant tumor types of various organs, including the ovary and colorectum (43–45), and in the present study, a prognostic value for these proteins was not observed in patients with stage III CC receiving adjuvant FOLFOX-4 treatment. SOX2, a transcription factor that serves as a critical regulator of stem cell maintenance and cell-fate decisions, is frequently used as a CSC marker in various malignant tumor types, including skin squamous cell carcinoma, bladder cancer and colorectal cancer (46–48). Many studies reported that SOX2 could serve as a poor prognostic marker in patients with various types of cancer, including rectum, breast and oral cavity cancer (26,32,34). However, contradictory results have been reported (49–51) and in the present study, the expression of SOX2 indicated a favorable prognosis in patients with stage III CC with adjuvant FOLFOX-4 chemotherapy. This may be due to another role of SOX2, as SOX2 decreases the expression levels of cyclin D1 and phosphorylated retinoblastoma, and increases the expression levels of p27, inducing cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis (52). Additionally, SOX2 directly trans-activates phosphatase and tensin homolog in gastric cancer (53). These results indicated that the prognostic value of CSC markers in cancer may depend on the types of cancer and their stage.

In the present study, ABCC2 was associated with a prolonged DFS, and ABCG2 with prolonged DFS and OS. These results were contradictory to our original hypothesis that expression of ABC transporters may be associated with a reduced prognosis following chemotherapy. This may be associated with role of ABCC2 and ABCG2 in phase II metabolism of platinum-based anticancer agents (54). Limiting platinum-DNA adduct formation by conjugation with sulfur-containing molecules, including glutathione, is one of the major cellular mechanisms involved in resistance against platinum-based anticancer agents, including cisplatin or oxaliplatin (55). Sensitivity to platinum-based anticancer agents is associated with cellular glutathione concentration (55–58). ABCC2 is one of the glutathione transporters, which exports glutathione outside the cell and decreases the concentrations of glutathione (56). Theile et al (59) reported that 5-FU induces overexpression of ABCC2 and proposed that upregulation of ABCC2 by 5-FU may favor the synergistic action of the drug combination in the FOLFOX-4 regimen. Previous studies reported that ABCG2 is associated with glutathione transport (60,61). Krzyżanowski et al (60) reported that the expression levels of glutathione were decreased in cells that overexpressed ABCG2. Brechbuhl et al (61) reported that cells that overexpress ABCG2 indicate an increase in basal extracellular glutathione levels. Hlavata et al (24) and Mirakhorli et al (25) investigated the clinical implication of ABCC2 expression in a small number of CC samples treated with a 5-FU containing regimen and FOLFOX, respectively. Hlavata et al (24) reported no clinical significance for the transcript level of ABCC2; however, Mirakhorli et al (25) reported that the incidence of metastasis or recurrence was not significantly reduced in the ABCC2 positive group, in accordance with the results of the present study. In contrast, Lin et al (31) reported that high ABCG2 expression was associated with resistance to palliative FOLFOX treatment in patients with metastatic CC, indicating that the biological role of ABC transporters in the chemoresponse may vary according to cancer stage.

The expression of ABC transporters has been indicated to be one of the factors that enhance the survival of CSCs during chemotherapy and multiple ABC transporters, including p-glycoprotein and ABCG2, have been identified in CSCs (14). The association between the expression of CSC markers and the expression of ABC transporters, including the associations between LGR5 and ABCC2, and SOX2 and ABCC3, was examined in the present study, suggesting an association between CSCs properties and ABC transporter expression.

The present study presents a limitation in that it includes only retrospectively-collected cases. Further prospective studies with larger cohorts are required, in order to confirm the clinical use of these markers as prognostic marker for patients with CC. It was indicated that the expression of SOX2, ABCC2 and ABCG2 were associated with improved outcomes in patients with stage III CC, who post-operatively received chemotherapy with the FOLFOX-4 regimen. They may be beneficial prognostic markers in patients with CC who have received adjuvant FOLFOX treatment and promising candidate markers for a validation study on FOLFOX-4 therapy outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CC

colon cancer

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- CSC

cancer stem cell

- TMA

tissue microarrays

- IHC

immunohistochemical

- DFS

disease-free survival rate

- OS

overall survival rate

Funding

This study was supported by grant no. 09-2014-004 from the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Research Fund (Seongnam, South Korea).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

ES supervised the entire study, participated in study design and coordination as well as the writing of the manuscript. SHH and JWK made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. MK, JHK and KWL performed acquisition of data, and BHK and HK made substantial contributions to analysis of the data and were involved in revising draft critically for important intellectual content. HKO, DWK and SBK made substantial contribution to case collection and data acquisition and revising this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Research Using Human Subjects at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB no. B1512-326/302). The present study was exempt from obtaining written informed consent according to the bioethics of our country because it was a retrospective study, not expected to cause any harm, and the expected risk to the patients was very low.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haller DG, Catalano PJ, Macdonald JS, O'Rourke MA, Frontiera MS, Jackson DV, Mayer RJ. Phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in high-risk stage II and III colon cancer: final report of Intergroup 0089. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8671–8678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, Abt M, Burris H, III, Carrato A, Cassidy J, Cervantes A, Fagerberg J, Georgoulias V, et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2696–2704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lembersky BC, Wieand HS, Petrelli NJ, O'Connell MJ, Colangelo LH, Smith RE, Seay TE, Giguere JK, Marshall ME, Jacobs AD, et al. Oral uracil and tegafur plus leucovorin compared with intravenous fluorouracil and leucovorin in stage II and III carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol C-06. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2059–2064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, et al. Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer (MOSAIC) Investigators Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gramont A, Boni C, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Bonetti A, Clingan P, Marceau-Suissa J, Lorenzato C, André T. Oxaliplatin/5FU/LV in the adjuvant treatment of stage II and stage III colon cancer: efficacy results with a median follow-up of 4 years. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(Suppl 16):3501. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.23.16_suppl.3501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O'Connell MJ, Smith RE, Colangelo LH, Yothers G, Petrelli NJ, Findlay MP, Seay TE, Atkins JN, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maenhaut C, Dumont JE, Roger PP, van Staveren WC. Cancer stem cells: a reality, a myth, a fuzzy concept or a misnomer? An analysis. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:149–158. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien CA, Kreso A, Jamieson CH. Cancer stem cells and self-renewal. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3113–3120. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnenberg VS, Donnenberg AD. Multiple drug resistance in cancer revisited: the cancer stem cell hypothesis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:872–877. doi: 10.1177/0091270005276905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dave B, Chang J. Treatment resistance in stem cells and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:79–82. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crea F, Danesi R, Farrar WL. Cancer stem cell epigenetics and chemoresistance. Epigenomics. 2009;1:63–79. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinogradov S, Wei X. Cancer stem cells and drug resistance: The potential of nanomedicine. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2012;7:597–615. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fábián A, Barok M, Vereb G, Szöllosi J. Die hard: Are cancer stem cells the Bruce Willises of tumor biology? Cytometry A. 2009;75:67–74. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moitra K, Lou H, Dean M. Multidrug efflux pumps and cancer stem cells: Insights into multidrug resistance and therapeutic development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:491–502. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shervington A, Lu C. Expression of multidrug resistance genes in normal and cancer stem cells. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:535–542. doi: 10.1080/07357900801904140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillet JP, Efferth T, Remacle J. Chemotherapy-induced resistance by ATP-binding cassette transporter genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:237–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Zhang H, Assaraf YG, Zhao K, Xu X, Xie J, Yang DH, Chen ZS. Overcoming ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance: molecular mechanisms and novel therapeutic drug strategies. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;27:14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Artells R, Moreno I, Díaz T, Martínez F, Gel B, Navarro A, Ibeas R, Moreno J, Monzó M. Tumour CD133 mRNA expression and clinical outcome in surgically resected colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahlert C, Gaitzsch E, Steinert G, Mogler C, Herpel E, Hoffmeister M, Jansen L, Benner A, Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, et al. Expression analysis of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (ALDH1A1) in colon and rectal cancer in association with prognosis and response to chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4193–4201. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z, Dai W, Jiang L, Cheng Y. Over-expression of LGR5 correlates with poor survival of colon cancer in mice as well as in patients. Neoplasma. 2014;61:177–185. doi: 10.4149/neo_2014_016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Xia B, Liang Y, Peng L, Wang Z, Zhuo J, Wang W, Jiang B. Membranous ABCG2 expression in colorectal cancer independently correlates with shortened patient survival. Cancer Biomark. 2013;13:81–88. doi: 10.3233/CBM-130344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hlavata I, Mohelnikova-Duchonova B, Vaclavikova R, Liska V, Pitule P, Novak P, Bruha J, Vycital O, Holubec L, Treska V, et al. The role of ABC transporters in progression and clinical outcome of colorectal cancer. Mutagenesis. 2012;27:187–196. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ger075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirakhorli M, Shayanfar N, Rahman SA, Rosli R, Abdullah S, Khoshzaban A. Lack of association between expression of MRP2 and early relapse of colorectal cancer in patients receiving FOLFOX-4 chemotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:893–897. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saigusa S, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Yokoe T, Okugawa Y, Ioue Y, Miki C, Kusunoki M. Correlation of CD133, OCT4, and SOX2 in rectal cancer and their association with distant recurrence after chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3488–3498. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0617-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu HC, Liu YS, Tseng KC, Hsu CL, Liang Y, Yang TS, Chen JS, Tang RP, Chen SJ, Chen HC. Overexpression of Lgr5 correlates with resistance to 5-FU-based chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1535–1546. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1721-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hongo K, Tanaka J, Tsuno NH, Kawai K, Nishikawa T, Shuno Y, Sasaki K, Kaneko M, Hiyoshi M, Sunami E, et al. CD133(−) cells, derived from a single human colon cancer cell line, are more resistant to 5-fluorouracil (FU) than CD133(+) cells, dependent on the β1-integrin signaling. J Surg Res. 2012;175:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu YS, Hsu HC, Tseng KC, Chen HC, Chen SJ. Lgr5 promotes cancer stemness and confers chemoresistance through ABCB1 in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2013;67:791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Z, Zhang C, Wang H, Xing J, Gong H, Yu E, Zhang W, Zhang X, Cao G, Fu C. Multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 confers resistance to chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer by regulating reactive oxygen species and caspase-3-dependent apoptotic pathway. Cancer Lett. 2014;353:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin PC, Lin HH, Lin JK, Lin CC, Yang SH, Li AF, Chen WS, Chang SC. Expression of ABCG2 associated with tumor response in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving first-line FOLFOX therapy-preliminary evidence. Int J Biol Markers. 2013;28:182–186. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shima H, Kutomi G, Satomi F, Maeda H, Hirohashi Y, Hasegawa T, Mori M, Torigoe T, Takemasa I. SOX2 and ALDH1 as predictors of operable breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:2945–2953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J, Xia Q, Jiang B, Chang W, Yuan W, Ma Z, Liu Z, Shu X. Prognostic value of cancer stem cell marker ALDH1 expression in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshihama R, Yamaguchi K, Imajyo I, Mine M, Hiyake N, Akimoto N, Kobayashi Y, Chigita S, Kumamaru W, Kiyoshima T, et al. Expression levels of SOX2, KLF4 and brachyury transcription factors are associated with metastasis and poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1435–1446. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, Sullivan DC, et al., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th. Springer; New York: 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Health Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, corp-author. Comom Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 4.0, 2009. https://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/ctcae_4.03_2010-06-14_quickreference_5×7.pdf. [May 28;2009 ];

- 37.Huang EH, Wicha MS. Colon cancer stem cells: Implications for prevention and therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida A, Rzhetsky A, Hsu LC, Chang C. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:549–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sophos NA, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase gene superfamily: the 2002 update. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;143-144:5–22. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(02)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamanoi K, Fukuma M, Uchida H, Kushima R, Yamazaki K, Katai H, Kanai Y, Sakamoto M. Overexpression of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 in gastric cancer. Pathol Int. 2013;63:13–19. doi: 10.1111/pin.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Avoranta ST, Korkeila EA, Ristamäki RH, Syrjänen KJ, Carpén OM, Pyrhönen SO, Sundström JT. ALDH1 expression indicates chemotherapy resistance and poor outcome in node-negative rectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:966–974. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saigusa S, Inoue Y, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Kawamura M, Okugawa Y, Okigami M, Hiro J, Uchida K, Mohri Y, et al. Significant correlation between LKB1 and LGR5 gene expression and the association with poor recurrence-free survival in rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1308-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lugli A, Iezzi G, Hostettler I, Muraro MG, Mele V, Tornillo L, Carafa V, Spagnoli G, Terracciano L, Zlobec I. Prognostic impact of the expression of putative cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD166, CD44s, EpCAM, and ALDH1 in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:382–390. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomita H, Tanaka K, Tanaka T, Hara A. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in stem cells and cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:11018–11032. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang B, Liu G, Xue F, Rosen DG, Xiao L, Wang X, Liu J. ALDH1 expression correlates with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancers. Modern pathology: An official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology. Inc. 2009;22:817–823. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boumahdi S, Driessens G, Lapouge G, Rorive S, Nassar D, Le Mercier M, Delatte B, Caauwe A, Lenglez S, Nkusi E, et al. SOX2 controls tumour initiation and cancer stem-cell functions in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature13305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu F, Qian W, Zhang H, Liang Y, Wu M, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Gao Q, Li Y. SOX2 is a marker for stem-like tumor cells in bladder cancer. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amini S, Fathi F, Mobalegi J, Sofimajidpour H, Ghadimi T. The expressions of stem cell markers: Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, nucleostemin, Bmi, Zfx, Tcl1, Tbx3, Dppa4, and Esrrb in bladder, colon, and prostate cancer, and certain cancer cell lines. Anat Cell Biol. 2014;47:1–11. doi: 10.5115/acb.2014.47.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X, Yu H, Yang Y, Zhu R, Bai J, Peng Z, He Y, Chen L, Chen W, Fang D, et al. SOX2 in gastric carcinoma, but not Hath1, is related to patients' clinicopathological features and prognosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1220–1226. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim BW, Cho H, Choi CH, Ylaya K, Chung JY, Kim JH, Hewitt SM. Clinical significance of OCT4 and SOX2 protein expression in cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:1015. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-2015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng S, Pan Y, Wang R, Li Y, Cheng C, Shen X, Li B, Zheng D, Sun Y, Chen H. SOX2 expression is associated with FGFR fusion genes and predicts favorable outcome in lung squamous cell carcinomas. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3009–3016. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S91293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otsubo T, Akiyama Y, Yanagihara K, Yuasa Y. SOX2 is frequently downregulated in gastric cancers and inhibits cell growth through cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:824–831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S, Tie J, Wang R, Hu F, Gao L, Wang W, Wang L, Li Z, Hu S, Tang S, et al. SOX2, a predictor of survival in gastric cancer, inhibits cell proliferation and metastasis by regulating PTEN. Cancer Lett. 2015;358:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Croom E. Metabolism of xenobiotics of human environments. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2012;112:31–88. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415813-9.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burger H, Loos WJ, Eechoute K, Verweij J, Mathijssen RH, Wiemer EA. Drug transporters of platinum-based anticancer agents and their clinical significance. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ballatori N, Hammond CL, Cunningham JB, Krance SM, Marchan R. Molecular mechanisms of reduced glutathione transport: Role of the MRP/CFTR/ABCC and OATP/SLC21A families of membrane proteins. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:238–255. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El-akawi Z, Abu-hadid M, Perez R, Glavy J, Zdanowicz J, Creaven PJ, Pendyala L. Altered glutathione metabolism in oxaliplatin resistant ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 1996;105:5–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(96)04245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smitherman PK, Townsend AJ, Kute TE, Morrow CS. Role of multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2, ABCC2) in alkylating agent detoxification: MRP2 potentiates glutathione S-transferase A1-1-mediated resistance to chlorambucil cytotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:260–267. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Theile D, Grebhardt S, Haefeli WE, Weiss J. Involvement of drug transporters in the synergistic action of FOLFOX combination chemotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:1366–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krzyżanowski D, Bartosz G, Grzelak A. Collateral sensitivity: ABCG2-overexpressing cells are more vulnerable to oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;76:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brechbuhl HM, Gould N, Kachadourian R, Riekhof WR, Voelker DR, Day BJ. Glutathione transport is a unique function of the ATP-binding cassette protein ABCG2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16582–16587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.