Abstract

Capsanthin, the main carotenoid of red pepper fruits, is beneficial for human health. To breed pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) with high capsanthin content by marker-assisted selection, we constructed a linkage map of doubled-haploid (DH) lines derived from a cross of two pure lines of C. annuum (‘S3586’ × ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’). The map, designated as the SM-DH map, consisted of 15 linkage groups and the total map distance was 1403.8 cM. Mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for capsanthin content detected one QTL on linkage group (LG) 13 at 90 days after flowering (DAF) and one on LG 15 at 45 DAF; they were designated Cst13.1 and Cst15.1, respectively. Cst13.1 explained 17.0% of phenotypic variance and Cst15.1 explained 16.1%. We grouped DH lines according to the genotypes of markers adjacent to Cst13.1 and Cst15.1 on both sides. The DH lines with the alleles of both QTLs derived from ‘S3586’ showed higher capsanthin content at 45 and 90 DAF than the other lines. This is the first identification of QTLs for capsanthin content in any plant species. The data obtained here will be useful in marker-assisted selection for pepper breeding for high capsanthin content.

Keywords: pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), capsanthin, QTL, linkage map

Introduction

Pepper is an important horticultural crop worldwide. Among five cultivated species of pepper, Capsicum annuum (2n = 24 (2x)) is most widely used as a vegetable, a spice, and a food colorant. Pepper fruits, especially of mature red pepper, are an excellent source of natural pigments. The carotenoid pigments of pepper include capsanthin, capsanthin-5,6-epoxide, capsorubin, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin, antheraxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, β-carotene and cucurbitaxanthin A, and are synthesized and accumulated during fruit ripening. There are a great number of variations on the color and carotenoid content in pepper germplasm. And the most highly valued characteristic is high content of carotenoid. To breed and select carotenoid rich varieties, red-to-yellow isochromic fractions ratio and the capsanthin-to-zeaxanthin ratio are most useful and appropriate index together with the total carotenoid content (Hornero-Mendez et al. 2000, 2002, Wall et al. 2001). Because capsanthin is the main carotenoid, the relative content for capsanthin reaches 60% in carotenoid of red pepper fruits (Hornero-Mendez et al. 2002).

Capsanthin acts as a potential antioxidant, which has been shown to be effective as a free-radical scavenger. Also, capsanthin is usually esterified partially and/or totally with fatty acid in nature (Mínguez-Mosquera and Hornero-Mendez 1994a, 1994b), and it is shown that the radical scavenging ability of capsanthin is not influenced by esterification (Bae et al. 2012, Howard et al. 2000, Matsufuji et al. 1998). Furthermore, capsanthin and its esters reduces the risk of cancer due to exhibiting potent anti-tumor-promoting activity (Maoka et al. 2001). Additionally, capsanthin reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases because capsanthin had an HDL-cholesterol-raising effect on plasma without detectable differences in total cholesterol (Aizawa and Inakuma 2009).

Genetic control of carotenoid content in pepper fruits has been reported mainly for carotenoid biosynthesis pathways and color variation of fruits (Hurtado-Hernandez and Smith 1985). Genes for carotenoid biosynthesis pathway, for instance, PSY for phytoene synthase, Lcyb for lycopene-β-cyclase, Crtz for β-carotene hydroxylase and CCS for capsanthin–capsorubin synthase were identified so far (Bouvier et al. 1994, 1998 Hugueney et al. 1995, Romer et al. 1993). These are key genes for control yellow, orange and red colors of fruits (Huh et al. 2001, Lefebvre et al. 1998). Especially, CCS controls the red color (Tian et al. 2015). Further, orange and yellow colors of fruits are due to deletion or silencing of CCS gene (Ha et al. 2007, Lang et al. 2004, Rodriguez-Uribe et al. 2012).

Although there are many variations in pigment content in pepper germplasm, few studies about genetic controls of quantitative variations in carotenoid content have been reported. In one study, 4 QTLs were identified for fruit color of red pepper fruits, by quantifying lightness, chroma and hue parameters (Ben Chaim et al. 2001). In another study, 2 QTLs, pc8.1 and pc10.1, were identified that control chlorophyll content. The QTL pc8.1 also affected carotenoid content in ripe fruit. However, in subsequent generations there was not consistent effect of this QTL on carotenoid content (Brand et al. 2012).

Therefore, to access the genetic mechanisms for controlling content of red color pigment, capsanthin, in pepper, we mapped QTLs for the content in DH population derived from a cross between genetic resource and local cultivar. The genetic resource ‘S3586’ has high capsanthin content and local cultivar ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’ has low capsanthin content. In QTL mapping using population with fixed genotypes such as DH and recombinant inbred lines, utilization of all biological replication in one analysis is very important factor for reduction of nongenetic residual variance and increase in accuracy of the mapping (Broman and Sen 2009). Because our segregating population is DH, we can create multiple individuals with the same genotype for two experiments. Hence, we performed QTL mapping mainly using phenotypes from two datasets (Experiments 1 and 2) at one time. Further, we discuss how to increase capsanthin content by marker-assisted selection in practical breeding of pepper using QTLs detected in this study.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

The pepper genetic resource ‘S3586’ (C. annuum, Laboratory of Plant Genetics and Breeding, Shinshu University, Matsushima et al. 2009) was crossed with cultivar ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’ (C. annuum, Biotechnology Research Department, Kyoto Prefectural Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Technology Research Center, Seika, Kyoto, Japan, Minamiyama et al. 2012). A segregating doubled-haploid (SM-DH) population (n = 141) was developed by anther culture of an F1 plant as described by Dumas de Vaulx et al. (1981).

SM-DH lines were grown in a greenhouse of the Biotechnology Research Department (Seika, Kyoto, Japan) during the summers of 2013 (Experiment 1) and 2016 (Experiment 2). One plant of each SM-DH line was used for analysis. Seeds were sown in trays filled with vermiculite on 11 March 2013 and 4 February 2016. After 4 weeks, seedlings were transplanted into rockwool cubes; the cubes were placed on rockwool slabs on 17 May 2013 and 22 April 2016. The temperature in the greenhouse was maintained above 16°C. Plants were grown in hydroponic solution (M nutrient prescription, M Hydroponic Research Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan) with an electrical conductivity of 1.0 to 1.2 dS/m. Five fruits were harvested from each plant at each of the two ripening stages, 45 and 90 days after flowering (DAF). 45 DAF was turning color stage and 90 DAF was full maturity stage. Usually, we harvest ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’ at green mature stage, about 30 to 35 DAF, but at this stage capsanthin mostly is not detected. The peduncles and the seeds were removed, and the fruits were cut into small pieces and kept at −30°C until analysis.

Pigment extraction and saponification

Because a large proportion of capsanthin in pepper fruits is esterified with many kinds of fatty acids, qualitative and quantitative analysis of all capsanthin esters by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is very difficult. Generally, prior to HPLC analysis, capsanthin esters are hydrolyzed by saponification and then the capsanthin monomer is quantified (Hornero-Mendez et al. 2000, Howard et al. 2000).

Frozen sample (1 g fresh weight) was powdered using a mortar and pestle with sea sand and extracted with ethanolic pyrogallol (3% w/v). Extraction was repeated until the complete loss of color. All extracts were pooled and made up to 50 mL with ethanolic pyrogallol in a volumetric flask.

Each aliquot (10 mL) of the extract was mixed with 1 mL of potassium hydroxide (60% w/v). The tubes were placed in a 70°C water bath for 30 min with shaking continuously during saponification. The tubes were then cooled in water to room temperature, and 22.5 mL of sodium chloride (10 g/L) was added into each tube. Then the suspension was extracted three times with 15 mL of n-hexane/ethyl acetate (9:1 v/v). The upper layer was collected, and evaporated to dryness, and the residue was dissolved in 5 mL of ethanolic pyrogallol (3% w/v). All samples were filtered through 0.45-μm nylon membrane filters (Minisart-RC, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany).

HPLC analysis

Qualitative and quantitative HPLC analysis was performed according to the modified method of Goda et al. (1995) using a Shimadzu LC-10A quaternary pump equipped with a diode array detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and a Cosmosil 5C18-AR II reverse-phase column (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) protected by a guard cartridge (Nacalai Tesque). The oven was operated at 40°C. The sample injection volume was 10 μL. Samples were eluted with acetone in water as follows: 70% acetone for 5 min; 70%–90% linear gradient for 5 min; 90% acetone for 3 min; 90%–100% linear gradient for 20 min; and 100% acetone for 5 min. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. For quantification, a capsanthin standard was obtained from Extrasynthese S.A. (Lyon, France) and a β-carotene standard was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). All samples were analyzed before and after saponification. Loss of capsanthin during saponification was calculated from the loss of β-carotene. All analysis was carried out in 3 to 5 replications.

Heritability of traits

We used one-way ANOVA tables for phenotypes of the SM-DH lines in each experiment, using line (genotype) as a factor, to estimate heritability (h2) of capsanthin content at 45 DAF and 90 DAF. The phenotypic value of the ith line in the jth replicate, denoted as yij, is expressed as:

where μ is the intercept, gi is the effect of the ith line, eij is the residual error with gi~N(0, σg2) and eij~N(0, σe2), and m is the number of lines [m = 98 (45 DAF) or 94 (90 DAF)]. The expectations of sums of squares between and within lines, SB and SW, are expressed as:

and

From these formulae, estimates of the genetic variance and residual variance and , are obtained as:

Heritability was estimated as:

Isolation of genomic DNA and genotyping

Genomic DNA from the leaves of parental lines and the SM-DH population was isolated using a Nucleon PhytoPure DNA extraction kit (GE Healthcare UK Ltd., Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). Simple sequence repeat (SSR), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), sequence characterized amplified repeat (SCAR) and cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) primer pairs used in this study were selected on the basis of the published marker locus data (Gulyas et al. 2006, Kim and Kim 2006, Lee et al. 2004a, 2004b, Mimura et al. 2010, 2012, Minamiyama et al. 2006, 2007, Nagy et al. 2007, Sugita et al. 2006, 2013, Yi et al. 2006). Some SSR markers designed by Minamiyama et al. (2006) were newly mapped in this study (Table 1). PCR with SSR primers (Sugita et al. 2006, 2013) was performed by a post-labeling method with a bar-coded split tag as described in Konishi et al. (2015). PCR products were sequenced on a 3730×1 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Fragment length was determined by GeneMapper v3.7 software (Applied Biosystems). Labeling and analysis of SSR markers developed by Minamiyama et al. (2006) were performed as in that report. The 5′ ends of the forward primers were labeled with D2-, D3- or D4-fluorescent dye. PCR products were sequenced on a Beckman CEQ 200xL sequencer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Fragment length was determined on a CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system (Beckman Coulter). SNPs were genotyped by the Tm-shift method as in Fukuoka et al. (2008). PCR using SCAR and CAPs markers was performed as in Lee et al. (2004b), Gulyas et al. (2006) and Kim and Kim (2006). PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Table 1.

SSR markers newly mapped in this study

| Marker name | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Motif | Linkage group | Expected product size (bp)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMS_061-2 | cgatttcagtgggtgcctat | cgcactgaaaaaggagatgg | (gt)3...(tg)5...(tg)4...(ga)3 | 8 | 231 |

| CAMS_206-2 | tggagcatgcgtaaactcac | gtgactaaccccctgctgtc | (ac)22cc(ac)13 | 14 | 286 |

| CAMS_308 | gtgcttcgcatgcttgtatc | tctgaaagatgacagataattgtgg | (ta)3(tg)3(ta)7tgt(ag)11 | 14 | 215 |

| CAMS_487-2 | ggatgaggtcagtatgggact | tttgcatgcctgcagaataa | (ag)13 | 2 | 260 |

| CAMS_640-2 | atgggctaatgatcacgaca | cgtttacatgcgtcgttattg | (taa)8 | 14 | 158 |

| CAMS_667-2 | cgatccgtgaaagttactcaa | ggcaccccaaactttttagtc | (ag)12...(ga)4...(ga)3 | 9 | 222 |

| CAMS_818 | gctgcgacctcttcttcttc | ccccactaggtgggaataca | (ctt)5...(caa)5 | 14 | 268 |

| CAMS_852 | gctgaggttctagccaccag | tgtcgaaccgggacatagat | (tct)9 | 15 | 256 |

All markers in this Table were designed by Minamiyama et al. (2006).

Expected product size is indicated for ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’.

Construction of a linkage map and QTL analysis

AntMap software (Iwata and Ninomiya 2006) was used to construct LGs; the order of markers was determined using the Kosambi mapping function. The map was compared to the KL-DH map (Sugita et al. 2013; downloaded from VegMarks, http://vegmarks.nivot.affrc.go.jp/) and to the pepper genome (chromosomes) sequence data (CM334 ver. 1.55, Kim et al. 2014; available from the Pepper Genome website, http://peppergenome.snu.ac.kr). Composite interval mapping was performed in QTL Cartographer ver. 2.5 software (https://brcwebportal.cos.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm, Wang et al. 2005). Forward and backward stepwise regression was performed with a threshold of P < 0.05. To establish empirical LOD thresholds at the 5% level, 1000 permutation tests were performed. Seven datasets were prepared (Supplemental Table 1) using phenotypes of two cultivations (Experiments 1 and 2) at two ripening stages (45 and 90 DAF). These datasets were used to perform QTL mapping. In dataset No. 7, all of the phenotypes at two ripening stages (45 DAF and 90 DAF) in two cultivations were entered as a single phenotype.

Analysis of the effect of QTLs on capsanthin content

The SM-DH lines were grouped according to the genotypes of the markers linked to the QTLs, and the phenotypes of the groups were compared to each other.

Results

Phenotypic characterization of capsanthin content in parents and SM-DH population

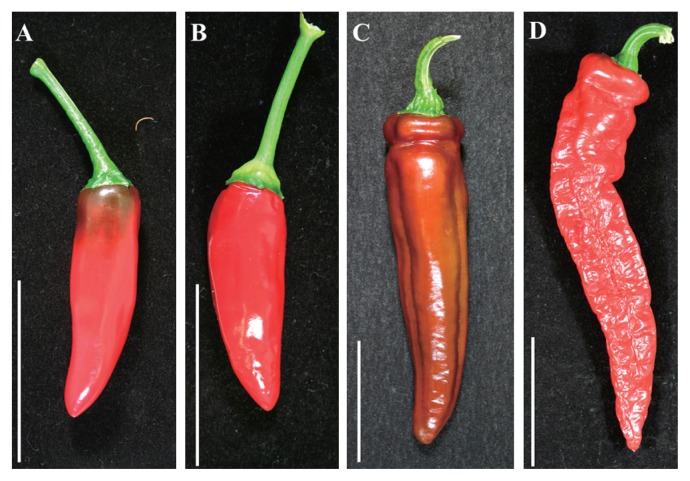

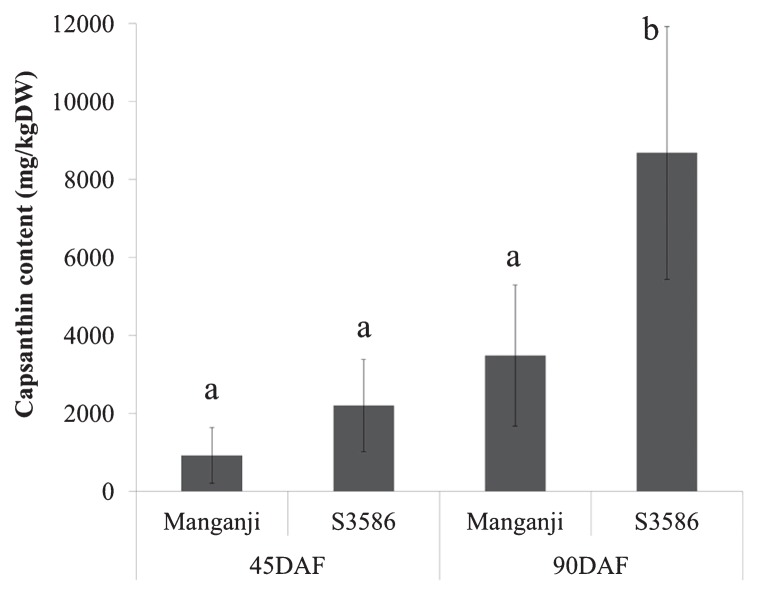

Capsanthin content increased during ripening (from 45 DAF to 90 DAF) in both parental lines and was higher in ‘S3586’ than in ‘Kyoto-Manganji’ at both ripening stages (Figs. 1, 2). This result agreed with that of Konishi and Matsushima (2011).

Fig. 1.

Fruits of parental lines at two ripening stages. (A) ‘S3586’, 45 DAF (B) ‘S3586’, 90 DAF (C) ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’, 45 DAF (D) ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’, 90 DAF. Bars indicate 5 cm.

Fig. 2.

Capsanthin content of parental lines at two ripening stages. Values are means of 7–9 measurements in two experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Means sharing the same letter are not significantly different according to the Tukey–Kramer multiple-comparison test.

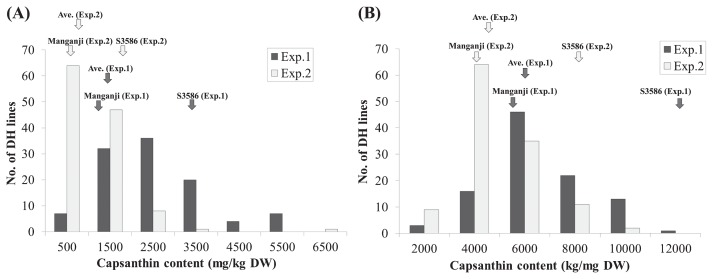

The capsanthin content in the SM-DH population evaluated in experiments 1 (2013) and 2 (2016) showed a normal distribution (Fig. 3). Capsanthin content of parental lines and average capsanthin content of SM-DH was higher in experiment 1 than in experiment 2 at both ripening stages (45 and 90 DAF) and a histogram of capsanthin content in experiment 2 shifted lower than in experiment 1. In 45 DAF, the distribution pattern in experiment 1 was different from that in experiment 2 (Fig. 3). Heritability of capsanthin content was quite low at 45 DAF and it was 0.155 at 90 DAF (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Frequency distribution of capsanthin content in SM-DH lines. (A) 45 DAF. (B) 90 DAF. Arrowheads indicate the mean values for the parents and average of SM-DH.

Table 2.

Heritability of capsanthin content

| Trait | h2 |

|---|---|

| Content at 45 DAF | −0.068 |

| Content at 90 DAF | 0.155 |

Linkage map construction

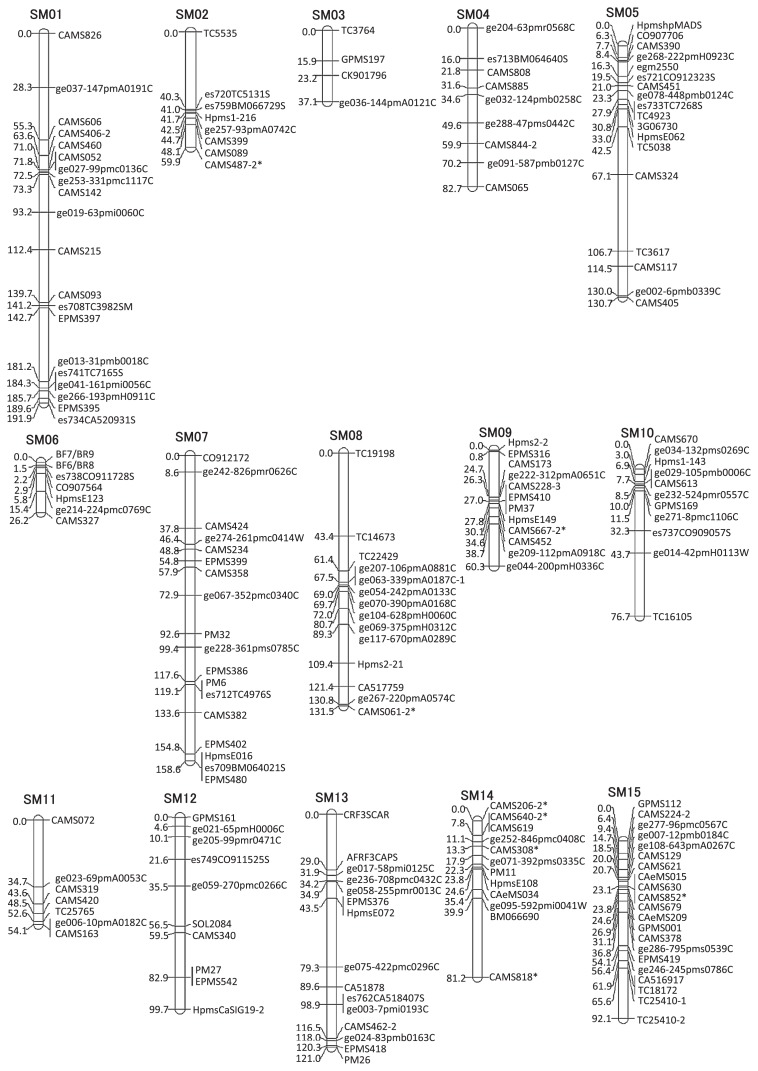

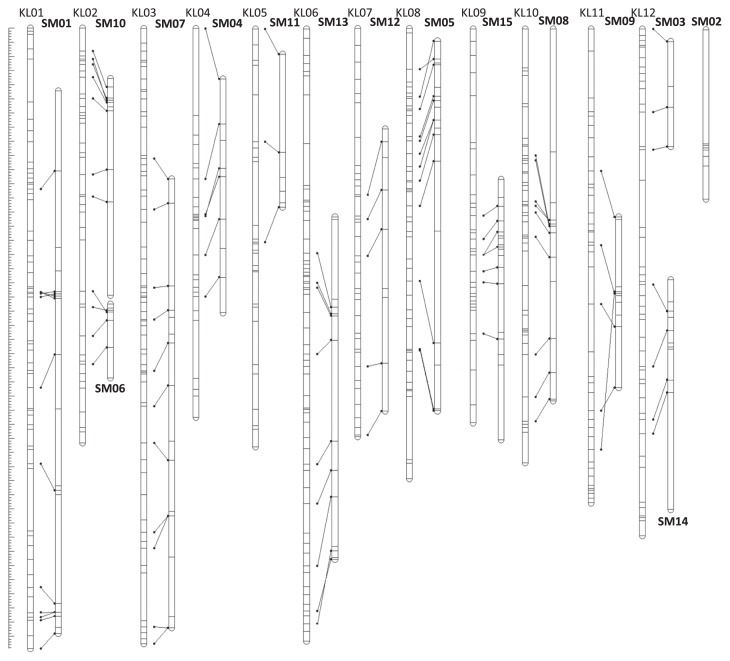

To construct a genetic map (designated as the SM-DH map), 160 SSR, 24 SNP, 3 SCAR and 1 CAPS markers were used. The map consisted of 15 LGs covering a total distance of 1403.8 cM (Fig. 4). The average distance between markers was about 9 cM. In this study, 8 new SSR markers were mapped (Table 1). We were able to assign 14 of the 15 LGs of the SM-DH map to LGs of the KL-DH map (Sugita et al. 2013), which covers nearly the entire genome of C. annuum (Fig. 5). Comparison with the pepper genome (CM334 ver. 1.55) using the BLAST program showed that the SM-DH map covered 75% of the genome.

Fig. 4.

Linkage map of the SM-DH population (‘S3586’ × ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’). SSR markers “PM”, “ge” and “es” were reported by Sugita et al. (2006, 2013), “CAMS” and “CAeMS” by Minamiyama et al. (2006) and Mimura et al. (2010, 2012), “Hpms” by Lee et al. (2004a), “HpmsE” by Yi et al. (2006), and “GPMS” and “EPMS” by Nagy et al. (2007). Newly mapped SSR markers are indicated with asterisks (*). SNP markers “TC”, “CA”, “CO” and “CK” were reported by Sugita et al. (2013). SCAR markers BF7/BR9 and BF6/BR8 were reported by Lee et al. (2004b) and CRF3SCAR by Gulyas et al. (2006). The CAPS marker AFRF3CAPS was reported by Kim and Kim (2006).

Fig. 5.

Comparison between KL-DH and SM-DH maps. KL01–KL12 are 12 linkage groups of the KL-DH map corresponding to the 12 pepper chromosomes (Sugita et al. 2013). SM01–SM15 are linkage groups of the SM-DH map constructed in this study. Identical markers on both maps are connected by lines.

QTL analysis

We carried out QTL analysis using 4 datasets on capsanthin content at 45 DAF and 90 DAF obtained from two experiments (Experiments 1 and 2). Further, we also performed QTL analysis using the data on the content at 45 DAF and 90 DAF from each experiment (Dataset 5 and 6, Supplemental Table 1).

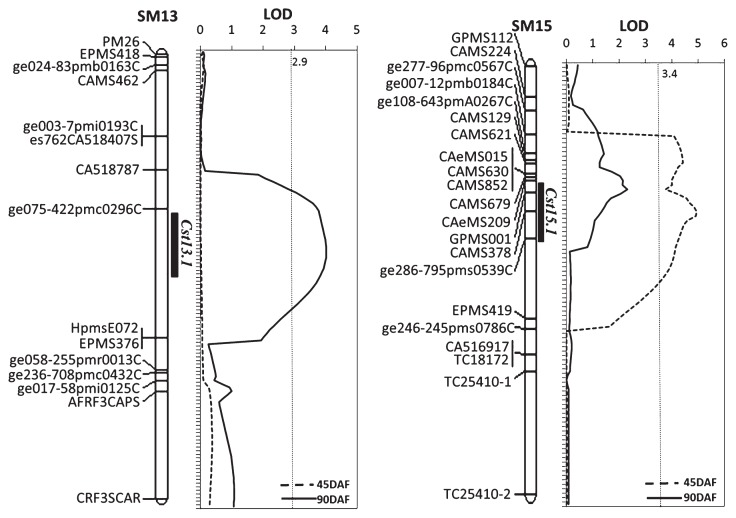

Analysis of capsanthin content at 45 DAF from two experiments detected a significant QTL on LG15 (LOD score, 4.95; Fig. 6, Table 3), which was designated Cst15.1. The LOD score peak was positioned between the SSR markers GPMS001 and CAMS378. The additive effect of this QTL was 501.0, and the allele that increased capsanthin content was derived from ‘S3586’ (Table 3). An insignificant LOD score peak at 90 DAF was observed close to Cst15.1 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Positions of two QTLs for capsanthin content on the SM-DH linkage map. Positions of QTLs with 1-LOD support intervals are shown by black boxes. Vertical dotted lines indicate the LOD thresholds.

Table 3.

QTLs for capsanthin content at each ripening stage detected in this study

| Experiment | Trait | Dataseta | LG | QTL ID | Markerb | Position | LOD | R2c | Additive effectd | Thresholde |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | Content at 45 DAF | 5 | 15 | Cst15.1 | GPMS001 CAMS378 |

28.9 | 5.0 | 16.1 | 501.0 | 3.3 |

| Content at 90 DAF | 6 | 13 | Cst13.1 | EPMS376, HpmsE072 ge075-422pmc0296C |

51.8 | 4.0 | 17.0 | 778.0 | 2.7 | |

| 1 | Content at 45 DAF | 1 | 15 | Cst15.1 | GPMS001 CAMS378 |

28.9 | 5.0 | 16.1 | 501.0 | 3.4 |

| Content at 90 DAF | 2 | 13 | Cst13.1 | EPMS376, HpmsE072 ge075-422pmc0296C |

51.8 | 4.0 | 17.0 | 778.0 | 2.8 | |

| 2 | Content at 90 DAF | 4 | 7 | Cst7.1 | CAMS424 ge274-261pmc0414W |

45.8 | 6.0 | 15.1 | −675.9 | 2.9 |

| 15 | Cst15.1 | CAeMS015 GPMS001 |

24.6 | 4.6 | 10.8 | 529.5 | 2.9 |

Details of datasets are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Nearest markers on both sides of QTL.

Percentage of phenotypic variation explained.

Positive values indicate alleles from ‘S3586’.

The significance threshold for QTL detection by 1000 permutations at P < 0.05.

Analysis of capsanthin content at 90 DAF from two experiments detected a significant LOD peak on LG13 (LOD score, 4.02; Fig. 6, Table 3), which was designated as Cst13.1. The LOD peak was positioned between the SSR markers EPMS376/HpmsE072 and ge075-422pmc0296C (Fig. 6). The additive effect of this QTL was 778.0 and its allele that increased capsanthin content was derived from ‘S3586’ (Table 3).

In analysis of the content from each single experiment (Dataset1–4), Cst15.1 was detected at 45 DAF in experiment 1, and at 90 DAF in experiment 2. Cst 13.1 was also detected at 90 DAF in experiment 1 (Table 3). A new QTL, Cst7.1 was detected only at 90DAF in experiment 2. At 45 DAF of experiment 2, we could not detect any significant QTL.

We also carried out QTL analysis using combined 45 DAF and 90 DAF data (Dataset 7), which we considered as variations of a single phenotype during ripening. In this analysis, we detected Cst15.1 but not Cst13.1 (Supplemental Fig. 1).

We grouped SM-DH lines according to the genotypes of markers adjacent to Cst15.1 and Cst13.1 on both sides and calculated the mean capsanthin content of each group at each ripening stage. Lines with the homozygous genotypes of Cst15.1 or Cst13.1 derived from ‘S3586’ had higher capsanthin content than the other lines at both 45 DAF and 90 DAF (Table 4). At 45 DAF, the ‘S3586’ allele of Cst15.1 seemed to be more effective in increasing capsanthin content than that of Cst13.1.

Table 4.

Capsanthin content in fruits of SM-DH lines grouped according to the genotypes of markers adjacent to the QTLs Cst15.1 and Cst13.1

| Traits | Genotypes of QTLs | N | Capsanthin content (mg/kg DW)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Cst15.1 | Cst13.1 | |||

| Content at 45 DAF | M | M | 48 | 956.9 a |

| M | S | 47 | 1219.0 ab | |

| S | M | 29 | 1723.0 b | |

| S | S | 28 | 1793.3 b | |

|

| ||||

| Content at 90 DAF | M | M | 45 | 3586.5 a |

| M | S | 45 | 4966.7 b | |

| S | M | 29 | 4974.8 b | |

| S | S | 28 | 5667.8 b | |

Data are means of two experiments.

Means sharing the same letter are not significantly different between line groups according to the Tukey–Kramer multiple-comparison test. M, homozygous for the ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’ allele; S, homozygous for the ‘S3586’ allele.

Discussion

In this study, to access the mechanisms for the genetic control in variation of capsanthin content of pepper (C. annuum), QTL mapping using SM-DH lines derived from a cross of high content genetic resource line, ‘S3586’ and cultivar ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’ was performed. Capsanthin content of SM-DH lines at two ripening stages (45 DAF and 90 DAF) differed between the two experiments, and its difference ascribes to the variation of the environmental (cultivation) conditions (Fig. 3). It is known that carotenoid accumulation is regulated by light signaling (Nisar et al. 2015). In Capsicum fruit, light irradiation at immaturity stage of fruit increases the expression of Psy gene for phytoene synthase (Nagata et al. 2015). Phytoene synthase is an enzyme upstream in capsanthin biosynthesis (Supplemental Fig. 3) and expression level of Psy and content of total carotenoid positively correlate (Rodriguez-Uribe et al. 2012). In this study, total global solar radiation at the nearest observation point from fruit setting (DAF 0) to immaturity stage (DAF 40) was 785 and 633 MJ/m2 in experiments 1 and 2, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 2). This difference of light condition may account for the difference of capsanthin content in two experiments. In order to verify this hypothesis, it is necessary to investigate into gene expression for carotenoid biosynthesis in the fields under different light condition.

To improve accuracy of QTL detection, we took into account variation among year in the analysis according to Broman and Sen (2009) and found Cst15.1 at 45 DAF and Cst13.1 at 90 DAF (Table 3). Cst 15.1 was detected at 45 DAF of experiment 1 and 90 DAF of experiment 2, but Cst 13.1 was detected at only experiment 1. Hence, it is possible that Cst 15.1 has more stable and large effect than Cst 13.1. We could select SM-DH lines with higher capsanthin content at both ripening stages in both experiments by using markers adjacent to the two QTLs (Table 4), suggesting that the QTLs have stable effects on capsanthin content under environmental conditions tested here.

It is important to breed high-capsanthin-content peppers to be used as health beneficial vegetables. Because the pepper fruits to be used as vegetables are usually harvested before they are fully matured (ex. 90 DAF), it is necessary to accumulate QTLs that increase capsanthin content at early stage (ex. 45 DAF). In particular, Cst15.1 seems to be efficient for this purpose (Tables 3, 4). Capsanthin is accumulated during the development of pepper fruit (Fig. 2), and Cst15.1 was the only QTL detected when capsanthin content at both 45 DAF and 90 DAF was considered as a variation of a single phenotype (Supplemental Fig. 1), suggesting that Cst15.1 affects capsanthin content at more than one stage.

The color of pepper fruits starts to change at 45 DAF (turning-color stage), and this change is completed at 90 DAF (full-maturity stage); one QTL was detected at each of the two stages when the analyses were conducted with the two cultivations at each ripening stage as phenotypes (Table 3). Hence, the two QTLs may have distinct effects on fruit ripening. However, it is very difficult to identify the candidate genes for the QTLs because the existing regions of the QTLs on the pepper genome (http://peppergenome.snu.ac.kr) are too large to narrow down. On the other hand, CCS gene for capsanthin-capsorubin synthase, a key enzyme for capsanthin biosynthesis (Supplemental Fig. 3), begins to be expressed when the fruits starting to ripe (Lefebvre et al. 1998). Also, CCS gene was mapped to chromosome 6 (Thorup et al. 2000), and Cst 13.1 was also mapped to the same chromosome. Additionally, lycopene ɛ-cyclase gene (LCY-E, Supplemental Fig. 3), that probably act in the lutein synthesis pathway not in the capsanthin synthesis pathway, was mapped to chromosome 9 (Thorup et al. 2000) as with Cst 15.1. However, to detect the candidate gene of Cst13.1 and Cst15.1 and to clarify the relationship of these QTLs with CCS and CLY-E, it is necessary to use the high-resolution QTL mapping and transcript quantification.

In spite of small h2 values for capsanthin content at 45 and 90 DAF (Table 2), the QTLs detected in this study explained more than 15% of the total phenotypic variation, suggesting that the marker sets flanking these QTLs derived from ‘S3586’ would be efficient tools to breed peppers with high capsanthin content by marker-assisted selection. Because the SM-DH map covers only 75% of the entire genome, it may be necessary to check whether other QTLs exist in the remaining 25% if additional markers are available.

In pepper, strategies to breed carotenoid-enriched cultivars have been so far limited, probably because of complicated phenotypic evaluation. Selection for capsanthin content using DNA markers linked to QTLs is highly effective. Many QTLs may affect carotenoid biosynthesis and make the plants fit under various environmental conditions. To identify more QTLs for carotenoid content, it is necessary to screen high-carotenoid-content materials from many landraces and genetic resources and to develop many DNA markers for detecting QTLs from those materials in the future.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. K. Matsushima and Dr. M. Minami of Shinshu University for providing the pepper genetic resource ‘S3586’. We also thank Dr. T. Sugita of Minami Kyushu University for providing some of the primers used in this study.

Literature Cited

- Aizawa, K. and Inakuma, T. (2009) Dietary capsanthin, the main carotenoid in paprika (Capsicum annuum), alters plasma high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels and hepatic gene expression in rats. Br. J. Nutr. 102: 1760–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae, H., Jayaprakasha, G.K., Jifon, J. and Patil, B.S. (2012) Variation of antioxidant activity and the levels of bioactive compounds in lipophilic and hydrophilic extracts from hot pepper (Capsicum spp.) cultivars. Food Chem. 134: 1912–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Chaim, A., Paran, I., Grube, R.C., Jahn, M., van Wijk, R. and Peleman, J. (2001) QTL mapping of fruit-related traits in pepper (Capsicum annuum). Theor. Appl. Genet. 102: 1016–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, F., Hugueney, P., d’Harlngue, A., Kuntz, M. and Camara, B. (1994) Xanthophyll biosynthesis in chromoplasts: isolation and molecular cloning of an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of 5,6-epoxycarotenoid into ketocarotenoid. Plant J. 6: 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, F., Keller, Y., d’Harlngue, A. and Camara, B. (1998) Xanthophyll biosynthesis: molecular and functional characterization of carotenoid hydroxylases from pepper fruits (Capsicum annuum L.). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1391: 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A., Borovsky, Y., Meir, S., Rogachev, I., Aharoni, A. and Paran, I. (2012) pc8.1, a major QTL for pigment content in pepper fruit, is associated with variation in plastid compartment size. Planta 235: 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman, K.W. and Sen, S. (2009) A guide to QTL mapping with R/qtl. Springer, New York, pp. 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas de Vaulx, R., Chambonnet, D. and Pochard, E. (1981) In vitro culture of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) anthers: high rate of plant production from different genotypes by +35°C treatments. Agronomie 1: 859–864. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka, H., Miyatake, K., Negoro, S., Nunome, T., Ohyama, A. and Yamaguchi, H. (2008) Development of a routine procedure for single nucleotide polymorphism marker design based on the Tm-shift genotyping method. Breed. Sci. 58: 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Goda, Y., Nakanishi, T., Sakamoto, S., Sato, K., Maitani, T. and Yamada, T. (1995) Analyses of coloring constituents in commercial paprika color by HPLC. J. Food Hygiene Safety (Japan) 37: 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gulyas, G., Pakozdi, K., Lee, J.S. and Hirata, Y. (2006) Analysis of fertility restoration by using cytoplasmic male-sterile red pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) lines. Breed. Sci. 56: 331–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, S.H., Kim, J.B., Park, J.S., Lee, S.W. and Cho, K.J. (2007) A comparison of the carotenoid accumulation in Capsicum varieties that show different ripening colours: deletion of the capsanthin-capsorubin synthase gene is not a prerequisite for the formation of a yellow pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 58: 3135–3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornero-Mendez, D., Gómez-Ladrón de Guevara, R. and Mínguez-Mosquera, M.I. (2000) Carotenoid biosynthesis changes in five red pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivars during ripening. Cultivar selection for breeding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48: 3857–3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornero-Mendez, D., Costa-García, J. and Mínguez-Mosquera, M.I. (2002) Characterization of carotenoid high-producing Capsicum annuum cultivars selected for paprika production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50: 5711–5716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, L.R., Talcott, S.T., Brenes, C.H. and Villalon, B. (2000) Changes in phytochemical and antioxidant activity of selected pepper cultivars (Capsicum species) as influenced by maturity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48: 1713–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugueney, P., Badillo, A., Chen, H.C., Klein, A., Hirschberg, J., Camara, B. and Kuntz, M. (1995) Metabolism of cyclic carotenoids: a model for the alteration of this biosynthetic pathway in Capsicum annuum chromoplasts. Plant J. 8: 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh, J.H., Kang, B.C., Nahm, S.H., Kim, S., Ha, K.S., Lee, M.H. and Kim, B.D. (2001) A candidate gene approach identified phytoene synthase as the locus for mature fruit color in red pepper (Capsicum spp.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 102: 524–530. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-Hernandez, H. and Smith, P.G. (1985) Inheritance of mature fruit color in Capsicum annuum L. J. Hered. 76: 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, H. and Ninomiya, S. (2006) AntMap: constructing genetic linkage maps using an ant colony optimization algorithm. Breed. Sci. 56: 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H. and Kim, B.D. (2006) The organization of mitochondrial atp6 gene region in male fertile and CMS lines of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Curr. Genet. 49: 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., Park, M., Yeom, S.I., Kim, Y.M., Lee, J.M., Lee, H.A., Seo, E., Choi, J., Cheong, K., Kim, K.T.et al. (2014) Genome sequence of the hot pepper provides insights into the evolution of pungency in Capsicum species. Nat. Genet. 46: 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, A. and Matsushima, K. (2011) Screening of breeding materials to increase bioactive components in sweet pepper. Hort. Res. (Japan) 10 (Suppl. 1): 151. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, A., Ohyama, A., Kakizaki, T., Miyatake, K., Yamagushi, H., Nunome, T. and Fukuoka, H. (2015) Optimization of post-labeling conditions for DNA markers using a bar-coded split tag (BStag). Bull. NIVTS. 14: 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Y.-Q., Yamagawa, S., Sasanuma, T. and Sasakuma, T. (2004) Orange fruit color in Capsicum due to deletion of Capsanthin-capsorubin synthesis gene. Breed. Sci. 54: 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.M., Nahm, S.H., Kim, Y.M. and Kim, B.D. (2004a) Characterization and molecular genetic mapping of microsatellite loci in pepper. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108: 619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.J., Yoo, E.Y., Shin, J.H., Lee, J., Hwang, H.S. and Kim, B.D. (2004b) Non-pungent Capsicum contains a deletion in the capsaicinoid synthetase gene, which allows early deletion of pungency with SCAR markers. Mol. Cells 19: 262–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, V., Kuntz, M., Camera, B. and Palloix, A. (1998) The capsanthin-capsorubin synthase gene: A candidate gene for the y locus controlling the red fruit colour in pepper. Plant Mol. Biol. 36: 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maoka, T., Mochida, K., Kozuka, M., Ito, Y., Fujiwara, Y., Hashimoto, K., Enjo, F., Ogata, M., Nobukuni, Y., Tokuda, H.et al. (2001) Cancer chemopreventive activity of carotenoids in the fruits of red paprika Capsicum annuum L. Cancer Lett. 172: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsufuji, H., Nakamura, H., Chino, M. and Takeda, M. (1998) Antioxidant activity of capsanthin and the fatty acid esters in paprika (Capsicum annuum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 46: 3468–3472. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima, K., Tsuji, A., Saritnum, O., Minami, M., Nemoto, K. and Ikeno, M. (2009) Evaluation of genetic resources of chili pepper (Capsicum spp.). Bull. Shinshu Univ. AFC 7: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mimura, Y., Minamiyama, Y., Sano, H. and Hirai, M. (2010) Mapping for axillary shooting, flowering date, primary axis length, and number of leaves in pepper (Capsicum annuum). Hort. J. 79: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mimura, Y., Inoue, T., Minamiyama, Y. and Kubo, N. (2012) An SSR-based genetic map of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) serves as an anchor for the alignment of major pepper maps. Breed. Sci. 62: 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamiyama, Y., Tsuro, M. and Hirai, M. (2006) An SSR-based linkage map of Capsicum annuum. Mol. Breed. 18: 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Minamiyama, Y., Tsuro, M., Kubo, T. and Hirai, M. (2007) QTL analysis for resistance to Phytophthora capsici in pepper using a high density SSR-based map. Breed. Sci. 57: 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Minamiyama, Y., Furutani, N., Inaba, K., Asai, S. and Nakazawa, T. (2012) A new sweet pepper variety, ‘Kyoto-Manganji No. 2’, with non-pungent fruit. Hort. Res. (Japan) 11: 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Mínguez-Mosquera, M.I. and Hornero-Mendez, D. (1994a) Formation and transformation of pigments during the fruit ripening of Capsicum annuum cv. Bola and Agridulce. J. Agric. Food Chem. 42: 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mínguez-Mosquera, M.I. and Hornero-Mendez, D. (1994b) Changes in carotenoid esterification during the fruit ripening of Capsicum annuum cv. Bola. J. Agric. Food Chem. 42: 640–644. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, M., Yoshida, C. and Matsunaga, H. (2015) Changes in the expression of carotenoid biosynthetic genes during light irradiation of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruit after harvest. Hort. Res. (Japan) 14: 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, I., Stagel, A., Sasvari, Z., Roder, M. and Ganal, M. (2007) Development, characterization, and transferability to other Solanaceae of microsatellite markers in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Genome 50: 668–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisar, N., Li, L., Lu, S., Khin, N.C. and Pogson, B.J. (2015) Carotenoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant 8: 68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Uribe, L., Guzman, I., Rajapakse, W., Richins, R.D. and O’Connell, M.A. (2012) Carotenoid accumulation in orange-pigmented Capsicum annuum fruit, regulated at multiple levels. J. Exp. Bot. 63: 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer, S., Hugueney, P., Bouvier, F., Camara, B. and Kuntz, M. (1993) Expression of the genes encoding the early carotenoid biosunthetic enzymes in Capsicum annuum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 196: 1414–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita, T., Yamaguchi, K., Kinoshita, T., Yuji, K., Sugimura, Y., Nagata, R., Kawasaki, S. and Todoroki, A. (2006) QTL analysis for resistance to phytophthora blight (Phytophthora capsici Leon.) using an intraspecific doubled-haploid population of Capsicum annuum. Breed. Sci. 56: 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sugita, T., Semi, Y., Sawada, H., Utoyama, Y., Hosomi, Y., Yoshimoto, E., Maehata, Y., Fukuoka, H., Nagata, R. and Ohyama, A. (2013) Development of simple sequence repeat markers and construction of a high-density linkage map of Capsicum annuum. Mol. Breed. 31: 909–920. [Google Scholar]

- Thorup, T.A., Tanyolac, B., Livingstone, K.D., Popovsky, S., Paran, I. and Jahn, M. (2000) Candidate gene analysis of organ pigmentation loci in the Solanaceae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 11192–11197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.L., Li, L., Shah, S.N.M. and Gong, Z.H. (2015) The relationship between red fruit colour formation and key genes of capsanthin biosynthesis pathway in Capsicum annuum. Biol. Plant. 59: 507–513. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, M.M., Waddell, C.A. and Bosland, P.W. (2001) Variation in β-carotene and total carotenoid content in fruits of Capsicum. HortScience 36: 746–749. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Basten, C. and Zeng, Z. (2005) Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5. Department of Statistics North Carolina State University, Raleigh: (https://brcwebportal.cos.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm). [Google Scholar]

- Yi, G., Lee, J.M., Lee, S., Choi, D. and Kim, B.D. (2006) Exploitation of pepper EST-SSRs and an SSR-based linkage map. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114: 113–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.