Abstract

Zingerone (ZGR), a phenolic alkanone isolated from ginger, has been reported to possess pharmacological activities such as anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects. This study was initiated to determine whether ZGR could modulate renal functional damage in a mouse model of sepsis and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. The potential of ZGR treatment to reduce renal damage induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) surgery in mice was measured by assessment of serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), lipid peroxidation, total glutathione, glutathione peroxidase activity, catalase activity, and superoxide dismutase activity. Treatment with ZGR resulted in elevated plasma levels of BUN and creatinine, and of protein in urine in mice with CLP-induced renal damage. Moreover, ZGR inhibited nuclear factor-κB activation and reduced the induction of nitric oxide synthase and excessive production of nitric acid. ZGR treatment also reduced the plasma levels of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, reduced lethality due to CLP-induced sepsis, increased lipid peroxidation, and markedly enhanced the antioxidant defense system by restoring the levels of superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase in kidney tissues. Our study showed renal suppressive effects of zingerone in a mouse model of sepsis, suggesting that ZGR protects mice against sepsis-triggered renal injury.

Keywords: Antioxidant, Renal injury, Renal toxicity, Sepsis, Zingerone

INTRODUCTION

As a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), sepsis is caused by viral infection and accounts for one-third of in-hospital deaths (1, 2). In response to viral infection, the activation of cytokines is one of host defense systems, however, uncontrolled or over-production of cytokines can cause overall tissue damages and multiple organ failure (3). Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is activated, blood level of nitric oxide (NO) and the synthesis of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are increased by CLP, which resulted in the cytotoxicity (4, 5). Therefore, the degree of organ failure can be reduced by inhibiting inflammatory cytokines and iNOS activity (4–6). Noting that the inhibiting the production of ROS and inflammatory cytokines is associated with the therapeutic functions in sepsis (7, 8), drug candidates capable of reducing cytokine production and ROS can also prevent or alleviate the pathological cascade of inflammation caused by sepsis.

Zingiber officinale is known to have beneficial properties such as antioxidative, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory activities (9). As an active compound of ginger rhizome (10), Zingerone (ZGR) has a variety of biological functions, including anti-apoptosis and anti-inflammation and protective responses against myocardial infarction and irritable bowel disorder (11–15). However, to our knowledge, the possible protective effects ZGR against renal damage have not been studied. In the current study, we seek to remedy this deficit by investigating the renal protective effects of ZGR in an animal sepsis model.

RESULTS

ZGR reduced CLP-induced renal tissue injury and the production of nitrate in renal tissue after CLP

Previous reports showed that treatment of cells or mice with ZGR inhibited LPS-induced expression and activity of sPLA2-IIA which contributes to vascular inflammation (16) and ZGR has anti-platelet aggregation activity (17). In those studies, ZGR was used from at 10 μM to 50 μM in human endothelial cells and from at 0.14, 0.36, or 0.72 mg/kg in mice (16, 17). Therefore, in this study, ZGR was also used from 0.07 to 0.72 mg/kg.

Table 1 showed the changes of nephrotoxic markers and urine protein levels by CLP; after 4 days CLP, the blood levels of BUN and creatinine, and urine protein were increased, which was significantly inhibited by the treatment of ZGR (two equal doses of ZGR, one at 12 h and the other at 50 h after CLP). However, there was no change in sham-operated or ZGR-only treated groups (Table 1). In addition, LDH, a general tissue injury marker, was also reduced by ZGR.

Table 1.

Effects of ZGR treatment on plasma levels of BUN and creatinine and urine level of protein in CLP-operated micea

| BUN (mg/dl) | Creatinine (mg/dl) | Urine protein (mg/12 hour) | LDH (U/dl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 17.2 ± 1.1 | 0.118 ± 0.011 | 2.2 ± 0.15 | 291 ± 23.3 |

| ZGR (0.72 mg/kg) | 18.1 ± 0.9 | 0.121 ± 0.017 | 2.3 ± 0.28 | 285 ± 23.6 |

| CLP | 78.4 ± 6.3 | 0.489 ± 0.035 | 14.1 ± 0.89 | 3520 ± 255.2 |

| CLP + ZGR (0.07 mg/kg) | 77.5 ± 5.1 | 0.492 ± 0.031 | 13.8 ± 0.55 | 3495 ± 205.6 |

| CLP + ZGR (0.14 mg/kg) | 65.2 ± 5.2* | 0.325 ± 0.023* | 8.5 ± 0.57* | 2584 ± 189.5* |

| CLP + ZGR (0.29 mg/kg) | 47.1 ± 3.5* | 0.288 ± 0.023* | 5.3 ± 0.41* | 1875 ± 156.7* |

| CLP + ZGR (0.72 mg/kg) | 29.7 ± 2.2* | 0.231 ± 0.022* | 3.5 ± 0.22* | 1285 ± 105.4* |

Each value represents the mean ± SD (n = 10).

Sham, sham-operated mice; ZGR, mice treated with ZGR (0.72 mg/kg body weight) at 12 and 50 h; CLP, CLP-operated mice; ZGR + CLP, mice treated with ZGR at 12 and 50 h after CLP surgery.

P < 0.05 as compared to CLP.

Next, we determined the effects of ZGR on the production of NO by measuring the stable end product of NO (nitrate levels) in vivo. Table 2 indicated that mouse plasma NO production was significantly increased by CLP (7-fold), which was reduced by ZGR treatment (upto 39%).

Table 2.

Effects of ZGR treatment on NO, TNF-α, IL-6 levels and renal MPO activity in CLP-operated micea

| NO (μM) | TNF-α (pg/ml) | IL-6 (pg/ml) | MPO (U/g tissue) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 32.52 ± 2.35 | 125.69 ± 10.21 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.06 |

| ZGR (0.72 mg/kg) | 34.26 ± 3.11 | 135.69 ± 12.38 | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.07 |

| CLP | 231.62 ± 15.98 | 582.35 ± 29.65 | 85.61 ± 4.95 | 3.89 ± 0.52 |

| CLP + ZGR (0.07 mg/kg) | 225.57 ± 20.31 | 548.25 ± 32.65 | 86.39 ± 5.15 | 3.89 ± 0.47 |

| CLP + ZGR (0.14 mg/kg) | 174.36 ± 15.37* | 358.24 ± 25.96* | 62.27 ± 2.58* | 2.69 ± 0.25* |

| CLP + ZGR (0.29 mg/kg) | 135.29 ± 12.17* | 304.58 ± 25.65* | 35.21 ± 3.58* | 2.03 ± 0.15* |

| CLP + ZGR (0.72 mg/kg) | 92.28 ± 8.57* | 189.51 ± 12.38* | 25.14 ± 2.39* | 1.25 ± 0.11* |

Each value represents the mean ± SD (n = 10).

Sham, sham-operated mice; ZGR, mice treated with ZGR (0.72 mg/kg body weight) at 12 and 50 h; CLP, CLP-operated mice; ZGR + CLP, mice treated with ZGR at 12 and 50 h after CLP surgery.

P < 0.05 as compared to CLP.

ZGR reduced CLP-induced inflammatory responses and lipid peroxidation in renal tissue after CLP

We tested whether ZGR treatment could ameliorate the production of inflammatory mediator, such as TNF-α and IL-6, in CLP-induced mice. Table 2 showed that blood levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were dramatically increased by CLP, which was inhibited by ZGR. In order to determine the effects of ZGR on the infiltration of leukocytes in renal tissue after CLP, we determined the MPO level after CLP. Table 2 indicated that ZGR inhibited upregulated MPO concentration by CLP. Moreover, during inflammatory response, inflammatory mediator proteins expression and MAPKs signaling pathways are closely involved in the regulation of inflammatory response. Therefore, we determined the effects of ZGR on the transcriptional regulation of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) such as p38 and janus kinase (JNK). Data showed that ZGR inhibited CLP-mediated expressions of COX-2, p38, and JNK (Supp. Table 1). ZGR also reduced the concentration of MDA, as a marker of lipid peroxidation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of ZGR treatment on MDA level and the activities of renal antioxidant enzymes in CLP-operated micea

| MDA (nM/mg protein) | GSH (nM/mg protein) | SOD (U/mg protein) | GSH-Px (U/mg protein) | CAT (U/mg protein) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 189.31 ± 11.65 | 26.37 ± 2.02 | 1.11 ± 0.03 | 2.38 ± 0.19 | 4.31 ± 0.25 |

| ZGR (0.72 mg/kg) | 191.57 ± 15.68 | 28.05 ± 1.89 | 1.09 ± 0.05 | 2.41 ± 0.24 | 4.52 ± 0.33 |

| CLP | 325.69 ± 30.25 | 16.89 ± 1.41 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 1.35 ± 0.12 | 2.95 ± 0.29 |

| CLP + ZGR (0.07 mg/kg) | 318.72 ± 27.68 | 17.05 ± 1.68 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 1.37 ± 0.11 | 2.89 ± 0.22 |

| CLP + ZGR (0.14 mg/kg) | 260.17 ± 18.98* | 21.08 ± 1.85* | 0.82 ± 0.07* | 1.78 ± 0.11* | 3.51 ± 0.31* |

| CLP + ZGR (0.29 mg/kg) | 224.58 ± 18.68* | 23.58 ± 2.32* | 0.89 ± 0.05* | 1.92 ± 0.14* | 3.95 ± 0.25* |

| CLP + ZGR (0.72 mg/kg) | 201.15 ± 17.52* | 24.85 ± 2.62* | 0.94 ± 0.08* | 2.14 ± 0.15* | 4.15 ± 0.28* |

Each value represents the mean ± SD (n = 10).

Sham, sham-operated mice; ZGR, mice treated with ZGR (0.72 mg/kg body weight) at 12 and 50 h; CLP, CLP-operated mice; ZGR + CLP, mice treated with ZGR at 12 and 50 h after CLP surgery.

P < 0.05 as compared to CLP.

ZGR ameliorated CLP-induced oxidative stress in renal tissue after CLP

We tested the possible beneficial effects of ZGR on CLP-induced oxidative stress by measuring the antioxidant GSH and the oxidative stress associated enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and catalase (CAT). As shown in Table 3, total GSH levels and the activities of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT were not changed in ZGR-only treated or sham-operated mice. However, post-surgery treatment with ZGR increased total GSH and renal enzyme activities (Table 3). Moreover, ZGR suppressed the transcriptional expression levels of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT by CLP (Supplemental Table 1). Noting that nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a potential pathway to protective responses against oxidative stress, and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is one of the most important enzymes for antioxidant pathway (18, 19). Therefore, we determined the effects of ZGR on the induction of HO-1 and on the nuclear accumulation of Nrf2. Data showed that HO-1 protein expression was induced by ZGR (Fig. 1A) and ZGR mediated the translocation of Nrf2 from the cytosol to nucleus in a concentration-dependent manner (Supplemental Fig. 1). Therefore, these results indicate that the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling axis plays an important role in the anti-oxidant effects of ZGR.

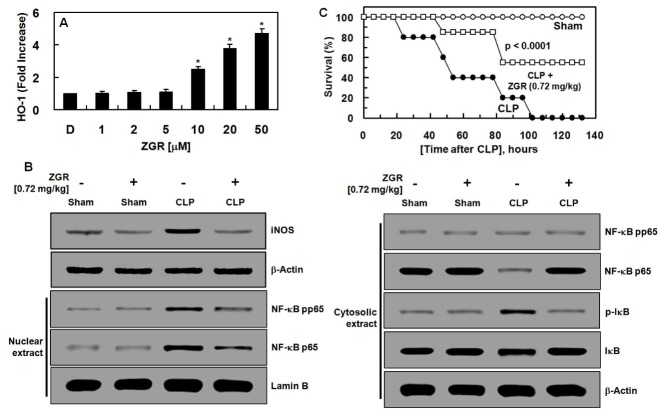

Fig. 1.

Effects of ZGR treatment on the expression levels of HO-1 in HUVECs, renal iNOS, IκB and NF-κB expression in CLP-operated mice and on CLP-induced septic lethality. (A) HUVECs were harvested after treatment with aloin (0–50 μM) for 16 h. The extracted proteins were subjected to ELISA for HO-1 expression. (B) Sham, sham-operated mice; Sham + ZGR, mice treated with ZGR (0.72 mg/kg body weight) at 12 and 50 h after sham operation. CLP, CLP-operated mice; CLP + ZGR, mice treated with ZGR (0.72 mg/kg body weight) at 12 and 50 h after CLP surgery (from left line). Western blots of iNOS, phosphor-IκB, IκB, phosphor-NF-κB, NF-κB, Lamin-B, and β-actin. The image is representative of results obtained from three different experiments. (C) Male C57BL/6 mice (n = 20) were administered ZGR at 0.72mg/kg (i.v. □) at 12 h and 50 h after CLP. Animal survival was monitored every 12 h for 132 h after CLP. Control CLP mice (●) and sham-operated mice (○) were administered sterile saline (n = 20). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to determine the overall survival rates versus CLP treated mice. D = 0.2% DMSO is the vehicle control. *P < 0.05 versus DMSO (A).

ZGR reduced iNOS level and translation of NF-κB p65

We determined the underlying mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory responses of ZGR by measuring levels of iNOS, IκB, and NF-κB proteins in kidney tissues of the mice. Post-treatment with ZGR reduced increased levels of iNOS protein by CLP (Fig. 1B). And, we tested whether ZGR could control the degradation of IκB by CLP and translocation of the subunit of NF-κB p65 from the cytosol to the nucleus. As shown in Fig. 1B, the translocation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB p65 to nucleus and activation of NF-κB p65 in nucleus and I inhibitory kappa B (IκB) phosphorylation in kidney significantly increased after CLP. Moreover, ZGR administration after CLP decreased NF-κB p65 activation and IκB phosphorylation compared with the CLP group. In addition, degradation of IκB was lower in the ZGR + CLP group than in the CLP-only group (Fig. 1B).

ZGR reduced CLP-induced lethality

In order to prove the beneficial responses of ZGR in renal tissues, we determined the effects of ZGR on CLP-induced lethality. To do this, ZGR (one at 12 h and the other 50 h after CLP) was injected intravenously. As shown in Fig. 1C, ZGR treatment increased the rate of survival of mice with sepsis (55%), according to a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (P < 0.0001). The marked improvement in survival rate achieved by the treatment suggested that ZGR might be of value in therapies for severe vascular inflammatory diseases, such as sepsis and septic shock.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to test the beneficial effect of ZGR, an active compound isolated from C. tricuspidata on renal injury in CLP-induced septic mice. Data showed that treatment with ZGR after CLP surgery dramatically improved CLP-induced renal damages. Moreover, the elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-6, NO, iNOS, and MPO by CLP was inhibited by ZGR. These improved effects were associated with an increase in the activity of the antioxidant enzyme and a reduction in the level of lipid peroxidation products in the kidney tissue. The molecular mechanism of beneficial effects of ZGR is mediated by the suppression of NF-κB activation. Consistent with previous reports (20–22), urine protein excretion, plasma BUN and creatinine levels were increased by CLP. In our study we also found that a change in kidney function after CLP surgery could be improved by ZGR because a significant inhibition in BUN, creatinine and urine protein levels was confirmed.

Under inflammatory condition, released NO is a pivotal inflammatory molecule and iNOS is induced and then NO is synthesized, which could influence the inflammation pathway (8). Noting that CLP-mediated kidney inflammatory injury is due to an increase in iNOS activity and consequently abnormal NO levels (4–6), our data suggested that ZGR inhibited CLP-induced NO production and iNOS expression in renal tissue.

It is well known that IL-6 and TNF-α are the major player in severe inflammatory conditions (3, 23). Based on the current findings that ZGR reduced the levels of both inflammatory regulators, IL-6 and TNF-α, ZGR could affect the crucial point of pathogenesis in the inflammation diseases. Since NF-κB is involved in the expression of inflammatory genes, it is a potential target for treating various inflammatory diseases (24). Here, we showed that the activation of NF-κB by CLP, which was inhibited by ZGR, indicating that the upregulated levels of iNOS, TNF-α, and IL-6 by CLP, as least in part, were affected by the interaction between ZGR and NF-κB. Recently, we reported the anti-septic effects of ZGR on high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a late mediator of sepsis, -mediated severe vascular inflammatory responses (11). We showed that ZGR reduced HMGB1 release in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-activated human endothelial cells, inhibited HMGB1-mediated inflammatory responses (11). Therefore, the renal protective activities of ZGR in this study were further confirmed by the anti-inflammatory activities of ZGR on the HMGB1-mediated severe vascular inflammatory responses (11).

The antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px, are considered to be the main defense against oxidative damage in tissues (25). Sepsis impaired the balance between free radical scavenging and cell antioxidant system production (26–27), and MDA is known as the major lipid peroxidation product and good index for oxidative stress (28–30). ZGR could be considered as a potential drug candidate for inflammatory renal diseases because SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, and MDA were positively controlled by ZGR in inflammatory renal tissues. Based on the current findings that ZGR reduced CLP-induced production of inflammation-related proteins (IL-6 and TNF-α), iNOS expression, and NO, which were accompanied by enhanced antioxidant defense system, we conclude that ZGR could be considered for the treatment of renal inflammatory diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

ZGR was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction reagent kits were obtained from Thermo Scientific Company (Rockford, lL). Antibodies against iNOS, IκB, phospho-IκB, NF-κB, phosphor-NF-κB, Lamin-B, and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Animals and cecal ligation and puncture

Male C57BL/6 mice (6–7 weeks old) were obtained from Orient Bio Co. (Sungnam, Republic of Korea) and were given a 12 d acclimatization period. The mice were housed under controlled temperature (20–25°C) and humidity conditions (40–45% RH), with a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle. They were fed a normal rodent pellet diet and had ad libitum access to water during acclimatization. To induce sepsis, the mice were first anesthetized with Zoletil (tiletamine and zolazepam, 1:1 mixture, 30 mg/kg) and Rompum (xylazine, 10 mg/kg). Sepsis was induced using cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) as previously described (31–32). As controls, sham-operated animals were used: in these mice, the cecum was exposed, but not ligated or punctured, and then returned to the abdominal cavity. Animals were randomly divided into 7 treatment groups (n = 10 each): sham-operated control; ZGR-only (0.72 mg/kg body weight) in 0.5% DMSO; CLP surgery only; and CLP + ZGR (0.07, 0.14, 0.29, or 0.72 mg/kg body weight). ZGR was intravenously injected at 12 h after CLP and again at 50 h after CLP. Blood and organ samples were collected 4 days after ZGR injection for functional assays. This protocol was approved by the Animal Care Committee at Kyungpook National University prior to conducting the study (IRB No. KNU 2017–102).

Sample preparation

Four days after ZGR injection, the mice were anesthetized as described above and sacrificed. Blood samples were collected from the posterior vena cava and allowed to clot. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 min, stored at −80°C until analyzed and was used for the assessment of plasma BUN and creatinine levels. Kidney samples were immediately removed and weighed. The kidneys were then minced with scissors and homogenized in 0.1 M phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.4); the tissue was fractionated under refrigeration by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The homogenate was stored at −80°C until analyzed in the various biochemical assays. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay.

Evaluation of nephrotoxicity and lactate dehydrogenase

Renal dysfunction was assessed by measuring the changes in levels of BUN and creatinine, and of protein in urine. BUN, creatinine, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), another important marker of tissue injury, were measured using commercial assay kits (Pointe Scientific, Linclon Park, MI). Urine samples were collected from each animal using a metabolic cage at 12 h after CLP surgery and the supernatant was obtained. Urinary protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay, using BSA as the protein standard.

Plasma nitrite/nitrate determination

Nitrite and nitrate concentrations in the plasma were determined using Griess reagents and vanadium solution (VCl3) as previously described (33). Briefly, 100 μl of VCl3 were added to 100 μl of sample, immediately followed by Griess reagents (0.1% N-1-naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride and 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid). After 30 min of color development, absorbance was determined by measuring optical density (OD) at 540 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan Austria GmbH, Austria). Concentrations were determined by comparing absorptions with those of a standard curve of sodium nitrite.

ELISA for TNF-α, IL-6, and HO-1

The plasma concentrations of IL-6, TNF-α, HO-1 were determined using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Values were measured using an ELISA plate reader (Tecan, Austria GmbH, Austria).

Renal myeloperoxidase activity

Renal myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was used as a quantitative indicator for neutrophil influx into the kidney; MPO activity was measured using ELISA kits (Abcam, UK).

Evaluation of oxidative stress markers

Lipid peroxidation was determined using a method to measure the formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARSs). The level of malondialdehyde (MDA) in kidney tissue was measured spectrophotometrically using an OxiSelect TBARS assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). MDA values were expressed as nM/mg protein. Total glutathione (GSH) contents of kidney tissue were measured as described previously (34). A tissue homogenate was prepared, and then samples were added to metaphosphoric acid and allowed to stand for 5 min to precipitate proteins. Phosphate buffer and 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitro-benzoic acid were added for color development. GSH was determined by measuring absorbance at 415 nm and absolute concentrations were calculated using a GSH standard (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Values of total GSH were expressed as nM/mg protein. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured using a SOD assay kit (Fluka). Values of SOD were expressed as U/mg protein. Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity was determined using the cellular activity assay kit CGP-1 (Sigma Aldrich). Values of GSH-Px were expressed as U/mg protein. Catalase activity (CAT) was determined by a CAT assay kit (Sigma Aldrich) using the decomposition rate of the substrate H2O2 as determined at 240 nm. Total CAT values were expressed as U/mg protein.

Western blots from renal tissue

Kidney samples were homogenized with radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer containing protease inhibitors; equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and were electroblotted overnight onto an Immobilon membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Or, nuclear and cytoplasmic protein was prepared using extraction kit (Thermo Scientific Company, Rockford, lL). The membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% low-fat milk-powder TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and were then incubated with primary antibodies for iNOS, IκB, phospho-IκB, phospho-NF-κB, NF-κB, Nrf2, Lamin-B, and β-actin, at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell culture

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from Cambrex Bio Science (Charles City, IA) and maintained as previously described (31, 35). HUVECs at passages 3–5 were used.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed independently at least three times. Values are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical significance of differences between test groups was evaluated using SPSS for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Statistical relevance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc test. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate significance.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant number: HI15C0001), by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIT, 2017M3A9G8083382 and 2018R1A5A2025272).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Russell JA. Management of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1699–1713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhry H, Zhou J, Zhong Y, et al. Role of cytokines as a double-edged sword in sepsis. In Vivo. 2013;27:669–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parratt JR. Nitric oxide in sepsis and endotoxaemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41(Suppl A):31–39. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Symeonides S, Balk RA. Nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999;13:449–463. x. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draisma A, Dorresteijn MJ, Bouw MP, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P. The role of cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase in endotoxemia-induced endothelial dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;55:595–600. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181da774b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent JL, Zhang H, Szabo C, Preiser JC. Effects of nitric oxide in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1781–1785. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9812004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadenas S, Cadenas AM. Fighting the stranger-antioxidant protection against endotoxin toxicity. Toxicology. 2002;180:45–63. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park KK, Chun KS, Lee JM, Lee SS, Surh YJ. Inhibitory effects of [6]-gingerol, a major pungent principle of ginger, on phorbol ester-induced inflammation, epidermal ornithine decarboxylase activity and skin tumor promotion in ICR mice. Cancer Lett. 1998;129:139–144. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sies H, Masumoto H. Ebselen as a glutathione peroxidase mimic and as a scavenger of peroxynitrite. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;38:229–246. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)60986-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee W, Ku SK, Bae JS. Zingerone reduces HMGB1-mediated septic responses and improves survival in septic mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017;329:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MK, Chung SW, Kim DH, et al. Modulation of age-related NF-kappaB activation by dietary zingerone via MAPK pathway. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao BN, Archana PR, Aithal BK, Rao BS. Protective effect of zingerone, a dietary compound against radiation induced genetic damage and apoptosis in human lymphocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;657:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemalatha KL, Prince PS. Preventive effects of zingerone on altered lipid peroxides and nonenzymatic antioxidants in the circulation of isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarcted rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2015;29:63–69. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banji D, Banji OJ, Pavani B, Kranthi Kumar C, Annamalai AR. Zingerone regulates intestinal transit, attenuates behavioral and oxidative perturbations in irritable bowel disorder in rats. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee IC, Kim DY, Bae JS. Inhibitory Effect of Zingerone on Secretory Group IIA Phospholipase A2. Nat Prod Commun. 2017;12:929–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee W, Ku SK, Kim MA, Bae JS. Anti-factor Xa activities of zingerone with anti-platelet aggregation activity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;105:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agca CA, Tuzcu M, Hayirli A, Sahin K. Taurine ameliorates neuropathy via regulating NF-kappaB and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling cascades in diabetic rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;71:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu M, Xu M, Liu Y, et al. Nrf2/ARE is the potential pathway to protect Sprague-Dawley rats against oxidative stress induced by quinocetone. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013;66:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber-Lang M, Sarma VJ, Lu KT, et al. Role of C5a in multiorgan failure during sepsis. J Immunol. 2001;166:1193–1199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhargava R, Altmann CJ, Andres-Hernando A, et al. Acute lung injury and acute kidney injury are established by four hours in experimental sepsis and are improved with pre, but not post, sepsis administration of TNF-alpha antibodies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo RF, Ward PA. C5a, a therapeutic target in sepsis. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2006;1:57–65. doi: 10.2174/157489106775244091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Osuchowski MF, Valentine C, Kurosawa S, Remick DG. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:19–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000034. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birben E, Sahiner UM, Sackesen C, Erzurum S, Kalayci O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5:9–19. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182439613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton JW. Free radicals and lipid peroxidation mediated injury in burn trauma: the role of antioxidant therapy. Toxicology. 2003;189:75–88. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatwalne MS. Free radical scavengers in anaesthesiology and critical care. Indian J Anaesth. 2012;56:227–233. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.98760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiao Y, Bai XF, Du YG. Chitosan oligosaccharides protect mice from LPS challenge by attenuation of inflammation and oxidative stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Yu Y, Zhang Z, Ding Y, Dai X, Li Y. Effect of polysaccharide from cultured Cordyceps sinensis on immune function and anti-oxidation activity of mice exposed to 60Co. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:2251–2257. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao JH, Xiao DM, Chen DX, Xiao Y, Liang ZQ, Zhong JJ. Polysaccharides from the Medicinal Mushroom Cordyceps taii Show Antioxidant and Immunoenhancing Activities in a D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mouse Model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 20122012 doi: 10.1155/2012/273435. 273435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung B, Kang H, Lee W, et al. Anti-septic effects of dabrafenib on HMGB1-mediated inflammatory responses. BMB Rep. 2016;49:214–219. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.4.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Liao H, Ochani M, et al. Cholinergic agonists inhibit HMGB1 release and improve survival in experimental sepsis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1216–1221. doi: 10.1038/nm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beutler E, Duron O, Kelly BM. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J Lab Clin Med. 1963;61:882–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Bae JS. ROS homeostasis and metabolism: a critical liaison for cancer therapy. Exp Mol Med. 2016;48:e269. doi: 10.1038/emm.2016.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.