Abstract

Objectives. To assess states’ provision of technical assistance and allocation of block grants for treatment, prevention, and outreach after the expansion of health insurance coverage for addiction treatment in the United States under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Methods. We used 2 waves of survey data collected from Single State Agencies in 2014 and 2017 as part of the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey.

Results. The percentage of states providing technical assistance for cross-sector collaboration and workforce development increased. States also shifted funds from outpatient to residential treatment services. However, resources for opioid use disorder medications changed little. Subanalyses indicated that technical assistance priorities and allocation of funds for treatment services differed between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states.

Public Health Implications. The ACA’s infusion of new public and private funds enabled states to reallocate funds to residential services, which are not as likely to be covered by health insurance. The limited allocation of block grant funds for effective opioid medications is concerning in light of the opioid crisis, especially in states that did not implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA; Pub L No. 111-148) markedly changed the financing of addiction treatment in the United States. The expansion of Medicaid, development of health insurance exchanges, extension of federal parity requirements, and mandate to include addiction treatment services in the essential health benefits package have greatly expanded the number of persons in the United States with health insurance that covers addiction treatment. The ACA’s emphasis on integrated models of care, including patient-centered medical homes, Accountable Care Organizations, and value-based purchasing models, has introduced new incentives to improve care coordination and integration.

These changes present new opportunities and challenges for the nation’s roughly 14 000 addiction treatment programs. As the ACA has prompted an increase in insurance financing for addiction treatment, many programs face the need to modernize their insurance billing systems.1 In addition, the movement toward value-based purchasing has introduced new incentives to integrate addiction treatment into mainstream medical care and increase cross-sector collaboration.

Single State Agencies (SSAs) oversee the public health infrastructure for addressing addiction prevention and treatment. These governmental agencies are charged with licensing and overseeing addiction treatment programs and allocating substance abuse prevention and treatment (SAPT) block grant funds2 and thus play an important role in assisting addiction treatment programs to meet these challenges. For example, SSAs provide assistance to local treatment programs in modernizing their billing systems, developing their workforces, and increasing collaboration with other service providers. States also have discretion over the use of block grant funds for addiction treatment services including medications. However, they are subject to federal guidelines on block grant use, which are determined through Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) policy language and the discretion of a government contract manager. SSAs are required to allocate a minimum of 20% of block grant funds to prevention services and a maximum of 20% to administrative costs. They are also required to prioritize coverage of treatment of pregnant and parenting women and HIV, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis services.

Research suggests that prior to 2014, when key ACA provisions took effect, SSAs only provided modest support to addiction treatment programs to adapt successfully to the new opportunities presented by the ACA.3 The most common forms of technical assistance provided by SSAs were related to collaboration with other service providers (e.g., medical providers, mental health providers, Federally Qualified Health Centers) and training to increase the number of addiction treatment counselors. A majority of SSAs also provided technical assistance related to Medicaid certification and information technology–electronic health record infrastructure. Few SSAs reported offering technical assistance with insurance enrollment and outreach or assistance to help addiction treatment providers become in-network providers with private insurance plans.3 In the years since the ACA’s key provisions took effect, it has remained unclear whether states have made new investments in technical assistance.

It is also uncertain how states have responded to the infusion of new health insurance financing to pay for addiction treatment precipitated by the ACA. Prior to passage of the ACA and the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, private and public insurers typically offered limited and constrained coverage for addiction services, and about half of all Americans who received addiction treatment services were uninsured.4 Addiction treatment was funded primarily through the federal block grant and other state and local funds.5 It is estimated that almost 3 million US persons with a substance use disorder have gained access to health insurance coverage for addiction treatment through the ACA.6,7

Increased insurance coverage for addiction treatment could allow states to redeploy federal block grant and local and state funds that were previously used to cover uninsured patients. States could use these recaptured funds to cover services for which health insurance coverage has often been inadequate, such as residential treatment and recovery support services. Early evidence suggests that in Medicaid expansion states, payment for the addiction treatment of many low-income patients has shifted from the SAPT block grant to Medicaid.1,8 Using data from the 2014 Treatment Episode Data Set, Maclean and Saloner found an increase in the percentage of patients who used Medicaid as a source of payment and a decrease in patients who relied on states and localities, including SAPT block grant funds, as a source of payment in Medicaid expansion states.8

This finding aligns with earlier work that found that in 2014, Medicaid expansion states reported they would likely increase funds for prevention services and outreach efforts and decrease funds for addiction treatment.3 However, it remains unclear what resource allocation choices Medicaid expansion states have made and whether differences have emerged between states that did and did not expand Medicaid.

In this study, we used data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, collected as part of the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (NDATSS), to assess (1) the types of technical assistance SSAs are providing to assist addiction treatment programs in the areas of workforce development, cross-sector collaboration, and health insurance system involvement; (2) whether their provision of technical assistance has changed since implementation of key provisions of the ACA in 2014; and (3) whether states have reallocated SAPT block grants after health insurance expansions resulting from the ACA. Given that Medicaid expansion has had a particularly significant impact on the publicly funded treatment system, we also stratified our analysis by Medicaid expansion status to compare differences across the 2 groups of states.

METHODS

Data are from the 2014 and 2017 NDATSS waves. Both waves included 15-minute Internet-based surveys with representatives of each state and the District of Columbia’s Single State Agency.

In each wave, the Survey Lab at the University of Chicago mailed SSA directors a packet containing a description of the study, an invitation to participate, a hyperlink to the Internet-based survey, and a letter of support from the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors. The study team identified SSA directors through a publicly available directory. The Survey Lab asked SSA directors to complete the survey themselves or designate a senior manager most knowledgeable within the agency to complete the survey. Five business days after the packets were mailed, the Survey Lab contacted all SSA directors via e-mail and gave them the same information in electronic format. The Survey Lab sent a follow-up e-mail to directors who did not respond to the packet or initial e-mail. In addition, the study team conducted telephone follow-ups with directors who did not reply to the follow-up e-mails.

Data collection occurred November 2013 through July 2014 and February 2017 through September 2017 for the first and second waves, respectively. The response rate was 98% in 2014 (n = 50) and 96% in 2017 (n = 49). Because we report data from a census of SSAs, we did not calculate inferential statistics.

We measured provision of technical assistance to addiction treatment programs by 9 dichotomous variables. SSAs reported whether they provided technical assistance to addiction treatment programs to

create information technology–electronic health records infrastructure,

obtain Medicaid certification,

become approved in-network providers within private insurance plans,

lead a formal planning process to assist treatment programs in insurance enrollment and outreach to newly eligible groups,

collaborate with Federally Qualified Health Centers,

collaborate with other medical providers,

collaborate with mental health providers,

collaborate with criminal justice–related organizations (e.g., probation and parole offices), and

provide education–training to increase the number of addiction treatment counselors.

SSAs reported on the percentage of SAPT block grants devoted to

prevention,

addiction treatment,

administrative costs,

outreach services, and

other.

Agencies also reported how SAPT funds devoted to addiction treatment services were distributed among outpatient treatment, intensive outpatient treatment, detoxification treatment, short-term residential treatment, long-term residential treatment, methadone maintenance, and buprenorphine and oral and injectable naltrexone treatment. In addition, SSAs reported whether state funds, other than those through Medicaid, were used to subsidize the availability of buprenorphine for publicly funded treatment clients. There were 2 additional questions in the 2017 survey regarding funding: another subcategory of treatment was added (recovery support services and initiatives), and SSAs were asked about the use of other state funds (nonblock grant and non-Medicaid) to subsidize the availability of oral and injectable naltrexone.

RESULTS

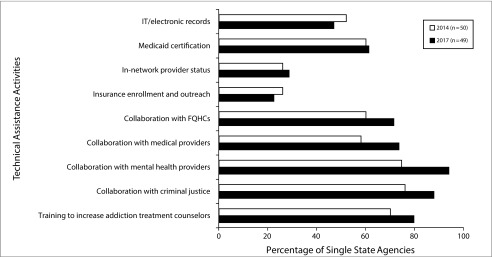

The percentage of states providing technical assistance to create information technology–electronic health records infrastructure increased by 5.1 percentage points over the study period, whereas the percentage of states providing technical assistance to assist treatment programs in insurance enrollment and outreach declined by 3.6 percentage points over the same period (Figure 1). Technical assistance in all other areas increased over the study period. The largest increases were related to collaboration with mental health providers (increased by 19.3 percentage points), medical providers (by 15.5 percentage points), Federally Qualified Health Centers (by 11.4 percentage points), and organizations involved with the criminal justice system (by 11.8 percentage points). The percentage of SSAs providing technical assistance to increase the number of addiction treatment counselors rose by 9.6 percentage points.

FIGURE 1—

Technical Assistance Provided by Single State Agencies to Addiction Treatment Providers by Type of Assistance: United States, 2014–2017

Note. IT = information technology; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center.

Allocation of Block Grant Funding

Despite increases in Medicaid coverage, the percentage of block grant funds allocated to prevention versus those allocated to addiction treatment changed little from 2014 to 2017. Prevention decreased by 2.0 percentage points (from 24.4% to 22.4%), and addiction treatment increased by 2.9 percentage points (from 67.0% to 69.9%).

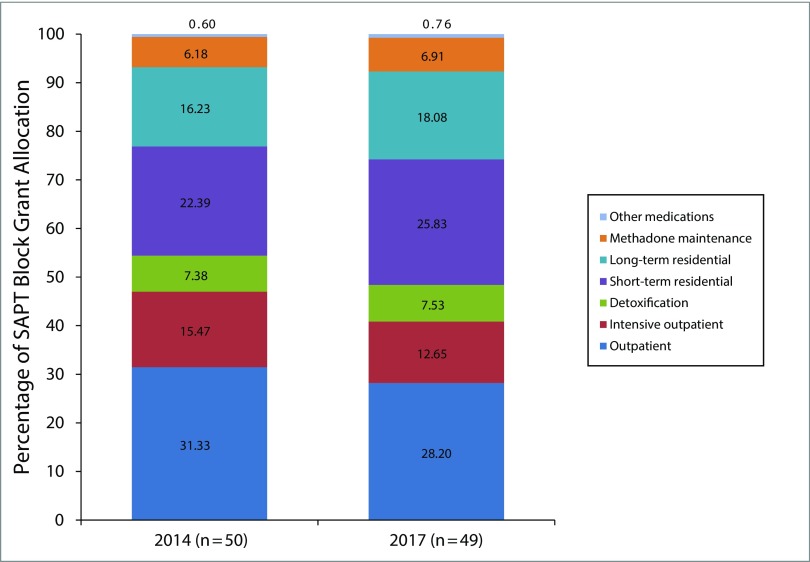

Overall, allocation of SAPT block grant funding for addiction treatment services shifted only slightly over the study period (Figure 2). The percentage of block grant funds devoted to outpatient treatment and intensive outpatient treatment decreased by 3.1 percentage points and 2.8 percentage points, respectively. Allocation of block grant funds to both short-term and long-term residential treatment increased by 3.4 percentage points and 1.9 percentage points, respectively.

FIGURE 2—

Allocation of Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment (SAPT) Block Grants for Addiction Treatment: United States, 2014–2017

The use of block grant funds for methadone maintenance increased by less than 1 percentage point from 2014 to 2017. The number of states using block grant funds for buprenorphine treatment decreased from 8 in 2014 to 5 in 2017; there was a similar decline for oral naltrexone treatment (from 6 to 4 states) and injectable naltrexone treatment (from 7 to 3 states). However, the number of states using other state funding (nonblock grant and non-Medicaid) to subsidize buprenorphine treatment increased from 15 to 20 states. In 2017, 11 states subsidized oral naltrexone treatment with other state funds and 19 states subsidized injectable naltrexone treatment.

Medicaid Expansion

We also examined changes in the provision of technical assistance and allocation of block grant dollars by Medicaid expansion status. Four additional states expanded Medicaid over the study period. However, given our data collection period, we did not code 2 states that expanded Medicaid in 2016 (LA and MT) as expansion states.

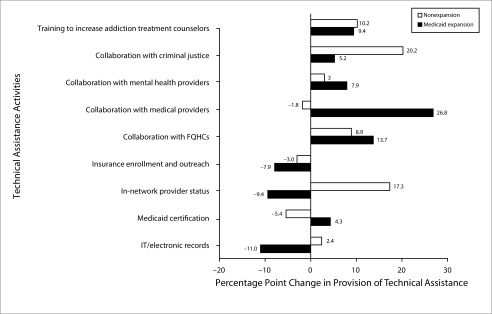

Among Medicaid expansion states, the provision of technical assistance increased in 3 key areas: Medicaid certification, collaboration with other providers (i.e., Federally Qualified Health Centers, medical providers, mental health providers, and criminal justice services providers), and training to increase addiction treatment counselors (Figure 3). Among nonexpansion states, technical assistance for in-network provider status and collaboration with criminal justice showed the largest increases, whereas technical assistance for Medicaid certification, insurance enrollment and outreach, and collaboration with medical providers decreased.

FIGURE 3—

Changes in Technical Assistance Provided by Single State Agencies to Addiction Treatment Providers by Type of Assistance and Medicaid Expansion Status: United States, 2014–2017

Allocation of block grant funding also varied between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states. The percentage of block grant funds allocated to prevention decreased by 4.0 percentage points in Medicaid expansion states (from 26.5% in 2014 to 22.5% in 2017) and did not change in nonexpansion states (22.2% in 2014 and 2017). The percentage of block grant funds allocated to treatment increased in both expansion and nonexpansion states; however, the increase was about 1 percentage point greater in expansion states (3.3 percentage points vs 2.4 percentage points). There was also a small increase in the percentage of funds allocated to outreach services.

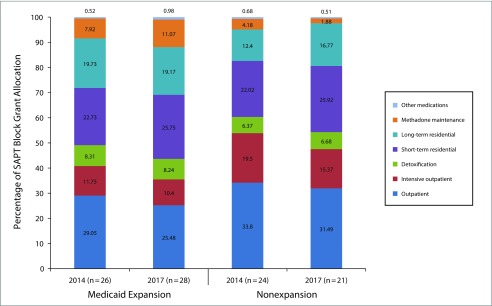

Within the treatment category, allocation of block grant funds for outpatient and intensive outpatient treatment services decreased in both expansion and nonexpansion states (Figure 4), with the decrease slightly greater in nonexpansion states (6.4 percentage points) than in expansion states (4.9 percentage points).

FIGURE 4—

Allocation of Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment (SAPT) Block Grants for Substance Abuse Treatment by Medicaid Expansion Status: United States, 2014–2017

The allocation of block grant funding for short-term and long-term residential services rose by 2.5 percentage points in expansion states but increased by 8.3 percentage points in nonexpansion states. The percentage of block grant funds allocated to methadone maintenance increased in expansion states by 3.2 percentage points and decreased in nonexpansion states by 2.3 percentage points; allocation of funds for other medications increased by 0.5 percentage points in expansion states and decreased by 0.2 percentage points in nonexpansion states. The number of states using block grant funds for other medications (e.g., buprenorphine, oral naltrexone, and injectable naltrexone) generally declined in Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states. The number of states using state funds other than block grants and Medicaid to subsidize buprenorphine increased in both expansion and nonexpansion states, although the increase was small.

DISCUSSION

States’ technical assistance efforts varied by Medicaid expansion status. Expansion states appeared to increase technical assistance for insurance enrollment and outreach, given the large numbers of people newly eligible for Medicaid coverage. Expansion states also made greater investments in new integrated care arrangements facilitated by the ACA.9

Although technical assistance for criminal justice interventions increased in both expansion and nonexpansion states, the increase was greater among nonexpansion states. Thus, nonexpansion states appear to be focusing technical assistance more heavily on collaborations outside of mainstream medical care.

In nonexpansion states, SSAs increased technical assistance for in-network provider status in private insurance plans. In the absence of Medicaid expansion, private insurance offers the main opportunity for expanded addiction coverage. Moreover, many addiction treatment providers were historically unable to bill for any type of insurance. Thus, even if patients were covered by private insurance, providers were unable to be reimbursed for treatment services. New opportunities for enrollment in state health insurance marketplaces and more generous coverage in these insurance plans may also help explain why SSAs in nonexpansion states focused more on this form of technical assistance.

The relative shifts in funds from outpatient to residential treatment in nonexpansion states were unexpected. This reallocation of resources to higher levels of care might reflect an increase in patients with severe opioid use disorder. It is also possible that nonexpansion states were simply reallocating funds to better balance funding for treatment across the continuum of care. In 2014, nonexpansion states allocated much more funding to outpatient treatment than expansion states (more than 50% of all treatment funds in nonexpansion states, compared with 39% in expansion states).

Recent analyses suggest that treatment programs in expansion states have been able to offset block grant payment for treatment services with Medicaid reimbursement.8 Therefore, we expected expansion states to have reallocated those recaptured SAPT funds to services that Medicaid has not traditionally covered, such as residential treatment, recovery support services, and methadone maintenance. In fact, we did observe small increases in allocation of funds to residential treatment and methadone maintenance in Medicaid expansion states. This may be in part explained by an increase in coverage of residential services and methadone maintenance in Medicaid programs from 2014 to 2017.10

Although we did find shifts in outpatient and residential services, overall changes in allocation of SAPT funds over the study period were small. Expansion states may have been responding to environmental uncertainty surrounding the future of Medicaid and the ACA during the study period and thus were reluctant to reallocate funding. Additionally, the limited change in funding in both expansion and nonexpansion states may be attributable to organizational inertia. Path dependence theory suggests that in responding to external demands, organizations (including state agencies) eventually narrow down their options in structure and functioning, which sets them upon a specific path.11,12 Although an abstract optimal allocation model might suggest sudden changes in the wake of the ACA, the developed path of routine behavior is less immediately responsive, making radical change difficult.

Interestingly, increases in allocation of block grant funding for methadone and other medications occurred exclusively in Medicaid expansion states. SSAs in both expansion and nonexpansion states reported an increase in the use of other state funds to subsidize buprenorphine. However, the number of states allocating block grant funds to buprenorphine and both formulations of naltrexone decreased.

The limited use of block grant funds for opioid use disorder medications is curious, given the dramatic rise in opioid-related overdose deaths and demand for opioid use disorder treatment. Prior research found that SSA funding targeting opioid use disorder medications was associated with an increase in the availability of buprenorphine and oral naltrexone.13 Thus, SSAs may be missing an important opportunity to expand access to care and to provide the highest-quality treatment of opioid use disorder, particularly in nonexpansion states.14

It is also possible that SSAs were using other funding streams such as the State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis Grants to finance opioid use disorder medications in mid-2017. However, given the short-term nature of the funding, it is unlikely that SSAs reallocated block grant funds in response to this one-time, 2-year increase in funding.

In 2014, SSAs in Medicaid expansion states reported they would likely increase funding for prevention services and outreach and decrease funds for addiction treatment.3 However, funding for prevention did not increase. Although it is disappointing that additional resources have not been allocated to prevention, SSAs likely increased funding for addiction treatment in response to the increased demand for opioid treatment. SSAs also face barriers to reallocating block grant funding because of requirements to prioritize target populations and services and to allocate a minimum of 20% of block grant funds to prevention.

Limitations

Our findings should be evaluated in light of several limitations. First, our survey only considered technical assistance efforts provided through the SSA and did not capture technical assistance provided directly to addiction treatment programs through other agencies, including the state Medicaid agency, Medicaid managed care organizations, SAMHSA, or the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Similarly, our survey did not capture additional sources of funding for addiction treatment such as the 21st Century Cures Act.

Second, we did not collect data on dollar amounts allocated, so we were unable to assess absolute changes in funding, which may be different from changes in the percentage of funds allocated. However, SAPT block grant funding has been relatively level in recent years, increasing only 2%: from $1.82 billion in 2014 to $1.858 billion in 2017.15 This represents a substantial decrease in the real value of funding because block grant funding has not kept up with health care inflation.

Third, our analyses did not account for the changing epidemiology of addiction (e.g., severity of the opioid crisis). Fourth, our results may underrepresent state investments in methadone because most opioid treatment programs are for-profit organizations and receive little to no block grant funds. Fifth, our self-report data may be susceptible to social desirability and recall biases.

Public Health Implications

Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states differed in their provision of technical assistance to addiction treatment services following implementation of the ACA. Although we found an overall increase in state support for cross-sector collaboration and workforce development, increased collaboration with medical providers was most concentrated in Medicaid expansion states. We also observed an overall increase in allocation of funds for residential services and a roughly equal decrease in funds for outpatient services over the study period. The infusion of new public and private insurance funds for addiction treatment from the ACA likely enabled states to reallocate other funds from outpatient to residential services, which are less likely to be covered by health insurance plans. Because the federal block grant totals over $2 billion annually, this reflects a significant change in the public health financing of addiction treatment of the uninsured in the United States.

Over time, differences in how states are investing resources could increase the already substantial variation in addiction service delivery systems observed across states. In particular, these disparities may affect uninsured and other vulnerable populations who rely on the block grant for addiction treatment. Moving forward, it will be important to understand the implications of this variability in nonexpansion and Medicaid expansion states. Nonexpansion states invested primarily in residential services and collaborations with criminal justice, whereas expansion states invested more heavily in methadone maintenance and mainstreaming addiction treatment through Medicaid Accountable Care Organizations, patient-centered medical homes, and other similar health care delivery models.

In the face of a growing opioid crisis, perhaps most concerning is the decrease in allocation of block grant funds for methadone in nonexpansion states and the limited allocation of block grant funds to buprenorphine and both formulations of naltrexone in both expansion and nonexpansion states. Although SSAs may be using other funding streams to finance opioid use disorder medications, only 32.8% of all addiction treatment programs offered methadone or buprenorphine in 2017 (Abraham et al., unpublished data). Reconsidering the regulations governing how SAPT funds can be used, such as including requirements that funded treatment programs provide these lifesaving medications, would provide key resources for a comprehensive public health response to the opioid crisis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research reported in this study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (grant R01DA034634).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

P. D. Friedmann was paid an honorarium and received reimbursement for travel for attendance at an Indivior advisory board meeting, received in-kind medication for research from Alkermes, and received training and reimbursement for local travel from Braeburn. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The institutional review boards at The Miriam Hospital, University of Chicago, University of South Carolina, and the University of Georgia approved this study.

Footnotes

See also McCarty, p. 838.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saloner B, Bandara S, Bachhuber M, Barry CL. Insurance coverage and treatment use under the Affordable Care Act among adults with mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(6):542–548. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Association of State Drug and Alcohol Abuse Directors. Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment (SAPT) block grant: prevention set-aside. Available at: http://nasadad.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/SAPTBG-Prevention-Set-Aside-2017-2.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- 3.Andrews C, Abraham A, Grogan CM et al. Despite resources from the ACA, most states do little to help addiction treatment programs implement health care reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(5):828–835. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2004–2014. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. BHSIS Series S-84, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 16-4986. Available at: https://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/dasis2/teds_pubs/2014_teds_rpt_natl.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2018.

- 5.Mark TL, Levit KR, Vandivort-Warren R, Coffey RM, Buck JA. Trends in spending for substance abuse treatment, 1986–2003. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(4):1118–1128. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank RG, Glied SA. Keep Obamacare to keep progress on treating opioid disorders and mental illnesses. The Hill. Available at: http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/healthcare/313672-keep-obamacare-to-keep-progress-on-treating-opioid-disorders. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 7.Frank RG, Glied SA. Corrected estimates: Keep Obamacare to keep progress on treating opioid disorders and mental illnesses. Harvard Medicaid School. Available at: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Key%20state%20SMI-OUD%20v3corrected.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2018.

- 8.Maclean JC, Saloner B. The effect of public insurance expansions on substance use disorder treatment: evidence from the Affordable Care Act. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w23342. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 9.D’Aunno T, Pollack H, Chen Q, Friedmann PD. Linkages between patient-centered medical homes and addiction treatment organizations: results from a national survey. Med Care. 2017;55(4):379–383. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews CM, Grogan CM, Tran Smith B et al. Medicaid benefits for addiction treatment expand after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1216–1222. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierson P. Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2000;94(2):251–267. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreyögg G, Sydow J. Organizational path dependence: a process view. Organ Stud. 2011;32(3):321–335. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Grogan CM et al. State-targeted funding and technical assistance to increase access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(4):448–455. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Association of State Drug and Alcohol Abuse Directors. Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment (SAPT) block grant. Available at: http://nasadad.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/SAPT-Block-Grant-Fact-Sheet-5.2.2018.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2018.