In the paper “Tau seeding activity begins in the transentorhinal (TRE)/entorhinal (EC) regions and anticipates phosphotau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease and PART” [10] published on May 11, 2018, Kaufman and colleagues aimed to investigate the origin of tau propagation using their HEK293 cell-based bioassay to quantify tau seeding activity of four brain regions from cases at progressive AD stages. This study was based on the premise that the hierarchical spread of tau pathology in AD occurs by prion-like transcellular propagation and, thus, brain areas representing the beginning of the chain of events associated with AD-tau pathogenesis should show the earliest evidence of tau seeding. Among other assertions, the authors suggest that this study design can answer whether precortical tau accrual represented here by locus coeruleus (LC) constitute AD’s earliest stage or is merely an epiphenomenon.

Neurodegenerative diseases feature relentless stereotypical spread of misfolded proteins through neuronal networks. Understanding the chronology and topography of these spread patterns is critical for developing biomarkers and therapeutic strategies relevant to the earliest AD stages. Neuropathological evidence points to the accrual of AD-type tau neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in subcortical structures preceding cortical involvement by tau in humans and at least in one animal model [13]. Tau burden in subcortical structures increases along AD progressive stages and correlates with structural and functional dysfunction [1, 7, 15]. However, whether subcortical tau accrual is part of AD pathogenesis remains a contested topic.

In Kaufman et al’s study, homogenates of human brain were transduced into wells containing 25,000 modified HEK293 cells. Cells were sorted by flow cytometry. The threshold for seeding activity was established as at least four standard deviations above the average signal obtained from tau KO mouse.

These brain homogenates were sourced from biopsy punches (4 mm × 0.1 mm) from four different brain regions: LC (representative of precortical tau stage 1b, prior known as Braak stage 0) [4], TRE/EC (stage I), STG (stage V) and VC (stage VI) obtained from 253 individuals with progressive Braak stages of tau distribution [3].

The authors reported an inconsistent tau seeding activity in bioassays transduced with LC homogenates from cases below stage III, whereas TRE/EC homogenates from same cases showed higher rates of tau seeding. Therefore, the authors repeatedly asserted in the manuscript that the origin of tau seeding activity in AD/PART is TRE/EC.

In this commentary, we lay out concerns about methodological shortcomings of this study that we believe undermine the conclusion that TRE/EC is the origin of tau seeding in AD.

Major concern

-

1

LC seeding assays were in a competitive disadvantage compared to cortical assays.

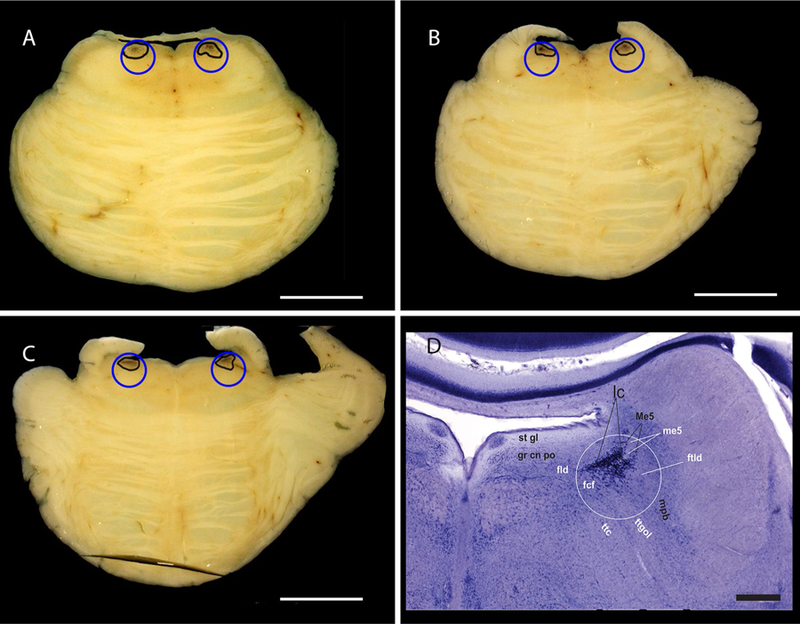

Brain homogenates were equalized by the amount of wet tissue (4-mm biopsy punches), thus creating a critically confounding bias. The LC diameter averages 2.0 mm at the superior 2/3rd and 3.8 mm at the inferior third in horizontal sections of fresh or formalin-fixed tissue in cases at stages ≤ I [6, 11, 15] (Fig. 1a–c). If Fig. S2 of the original paper illustrates the site of LC punching it comprises the rostral LC (level of the superior medullary velum). Thus, LC proper tissue would cover about ¼ of the punch volume (punch volume = πr2 × h = 3.14 × 22 × 0.1 = 1.25 mm3; LC volume in the punch = 3.14 × 12 × 0.1 = 0.31 mm3). The remaining of the punch would contain other structures which remain free of tau even at later AD stages (Fig. 1d). Note that Fig. S2 of the original paper is not at scale and may wrongly suggest that LC fills most of the punch area.

Fig. 1.

Horizontal sections of a brainstem fixed in formalin from a cognitively normal 58-year-old male classified as Braak stage 0 and having low Alzheimer’s Disease neuropathologic changes (A1B0C0) [12]. The sections contain the most rostral third (a), middle third (b) and caudal third (c) of the LC. The LC borders are traced in black and the blue circles represent the size of the biopsy punches (4 mm) in scale with LC. Scale bar: 1 cm. d Photograph of a Gallocyanin (Nissl)-stained horizontal histological Section (420 µm thick) of the pons from a 66-year-old cognitive control female. The white circle represents the area of the biopsy punch and the middle third of the LC is readily visible inside the circle. The areal fraction of the locus coeruleus within the white circle was estimated by point-counting with a 3 × 3 mm grid. The total number of hits within the circle was 128 and the number of hits onto the locus coeruleus 31. Therefore, the areal fraction of the locus coeruleus of the total circular area is 24.2%. The photograph also displays the structures surrounding the LC. Please note that the scale bar in Fig. 1d corresponds to 1 mm. The white circle has a diameter of 2 mm to account for an estimated 50% brain shrinkage after celloidin embedding and gallocyanin staining. After formalin fixation and prior to dehydration, the diameter of the circle would be 4 mm. fcf fasciculi confines of the medial longitudinal fascicle, fld dorsal longitudinal fascicle or bundle of Schütz, ftdl dorsolateral tegmental fascicle, grcnpo pontine central gray, lc locus coeruleus, Me5 mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus, me5 mesencephalic trigeminal tract, mpb medial parabrachial nucleus, stgl subependymal glial layer, ttc central tegmental tract, ttgol tegmentoolivary tract

One could argue that EC layer II, the one accruing most tau pathology at early AD stages, fills only 10% of the punch volume (0.13 mm3) balancing the LC disadvantage. However, the neuronal density in EC layer II approximates 28,000 neurons/mm3 (calculated from [9]), whereas in rostral LC neuron density averages 3236 neurons/mm3 [15]. In this scenario, biosensors would be transduced with homogenates of over 3500 EC layer II vs. only 1000 LC neurons.

This simple calculation clearly demonstrates that biosensors transduced with EC tissue started with a significant advantage over LC (plus surrounding tissue) homogenates. If measures are tainted by varying amounts of non-LC tissue, a higher variability in seeding activity should be expected. As the conclusion relied on the comparison of the quantity of tau signal detected in each biosensor, best practices would require that experiments start with the same amount of tau protein or, at least, the same number of neurons in each homogenate.

Other factors with potential impact

-

2

Besides LC, over 15 other brainstem, diencephalic, and basal forebrain nuclei, all interconnected to EC, accrue AD-tau at precortical stages (Braak ≤ 1) [8, 14].

This fact supports the claim that even if TRE/EC would show earlier tau seeding activity than LC, it seems premature to designate the TRE/EC as the origin of tau seeding in AD before testing seeding activity in these other nuclei. Moreover, neuropil threads are frequently encountered in AT8-stained TRE/EC regions even at Braak I (see fig. 2 of [2]). As all these structures interconnect with EC, it is not clear what amount of this neuropil tau belongs to endogenous EC cells and what amount should be attributed to afferents, e.g., from the LC and other earlier affected nuclei. Repeating the competitive bioassays using isolated neurons as a substrate may address this question.

-

3

LC shows a topographical gradient of vulnerability to AD that may impact the results.

The human LC consists of two columns. The middle LC third harbors twice as much tau inclusions in Braak stage 0 cases than the rostral and caudal thirds [5, 15]. Thus, assays with punches obtained from the less vulnerable rostral or caudal LC poles would be in an even greater disadvantage to cortical punches and contribute to the variability of seeding activity observed in LC assays.

References

- 1.Andres-Benito P, Fernandez-Duenas V, Carmona M, Escobar LA, Torrejon-Escribano B, Aso E, Ciruela F, Ferrer I (2017) Locus coeruleus at asymptomatic early and middle Braak stages of neurofibrillary tangle pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 43:373–392. 10.1111/nan.12386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K (2006) Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 112:389–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Del Tredici K (2011) The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol 121:171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K (2011) Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70:960–969. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318232a379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrenberg AJ, Nguy AK, Theofilas P, Dunlop S, Suemoto CK, Alho ATD, Leite RP, Rodriguez RD, Mejia MB, Rub U et al. (2017) Quantifying the accretion of hyperphosphorylated tau in the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus: the pathological building blocks of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 43:393–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.German DC, Walker BS, Manaye K, Smith WK, Woodward DJ, North AJ (1988) The human locus coeruleus: computer reconstruction of cellular distribution. J Neurosci 8:1776–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grinberg LT, Heinsen H (2017) Light at the beginning of the tunnel? Investigating early mechanistic changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 140:2770–2773. 10.1093/brain/awx261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grinberg LT, Rub U, Ferretti RE, Nitrini R, Farfel JM, Polichiso L, Gierga K, Jacob-Filho W, Heinsen H, Brazilian Brain Bank Study G (2009) The dorsal raphe nucleus shows phospho-tau neurofibrillary changes before the transentorhinal region in Alzheimer’s disease. A precocious onset? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 35:406–416. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinsen H, Henn R, Eisenmenger W, Götz M, Bohl J, Bethke B, Lockemann U, Püschel K (1994) Quantitative investigations on the human entorhinal area: left–right asymmetry and age-related changes. Anat Embryol (Berl) 190:181–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman SK, Del Tredici K, Thomas TL, Braak H, Diamond MI (2018) Tau seeding activity begins in the transentorhinal/entorhinal regions and anticipates phospho-tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease and PART. Acta Neuropathol 10.1007/s00401-018-1855-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keren NI, Lozar CT, Harris KC, Morgan PS, Eckert MA (2009) In vivo mapping of the human locus coeruleus. Neuroimage 47:1261–1267. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS et al. (2012) National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 123:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rorabaugh JM, Chalermpalanupap T, Botz-Zapp CA, Fu VM, Lembeck NA, Cohen RM, Weinshenker D (2017) Chemogenetic locus coeruleus activation restores reversal learning in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 140:3023–3038. 10.1093/brain/awx232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stratmann K, Heinsen H, Korf HW, Del Turco D, Ghebremedhin E, Seidel K, Bouzrou M, Grinberg LT, Bohl J, Wharton SB et al. (2016) Precortical phase of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-related tau cytoskeletal pathology. Brain Pathol 26:371–386. 10.1111/bpa.12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theofilas P, Ehrenberg AJ, Dunlop S, Di Lorenzo Alho AT, Nguy A, Leite RE, Rodriguez RD, Mejia MB, Suemoto CK, Ferretti-Rebustini RE et al. (2017) Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: a stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimers Dement 13:236–246. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]