Abstract

The journey of illness as lived by patients and caregivers is not routinely captured for systematic sharing or continuous learning. Consequently, far too many people face the uncertainty of what to expect when confronted with the challenges of illness and caregiving. Patients and caregivers muddle through unfamiliar territory without the benefit of the accumulated knowledge of others who have been on the journey before them. Why do patients and caregivers continually need to search out or reinvent solutions to manage their daily lives with life‐changing illness when others have surely faced similar challenges? Are not the lived experiences and contextual perspectives of patients and caregivers valuable for a learning health system? At PatientsLikeMe, an online patient research network, we believe it is not possible to realize the full potential of a continuously learning health system without the expertise and knowledge of patients and caregivers.

This paper describes the development of the Patient and Caregiver Journey Framework and related patient‐informed principles for design and measurement created by PatientsLikeMe in partnership with patients and caregivers using qualitative research methods, immersive observation and directed one‐on‐one conversations. These tools provide a person‐centric foundation upon which the knowledge and experience of patients and caregivers are collected, curated, aggregated and shared to support a data‐driven learning health community continuously powered by the people and for the people.

Keywords: continuous learning, empowerment, learning health community, patient empowerment, patient voice

“To receive a diagnosis of a chronic neurological illness is the beginning of a long journey into the unknown...[w]hen we begin any journey, we need a map. We need to pack and prepare for the journey. We need to know what to expect along the way.” Mary Baker and Lizzie Graham1

1. INTRODUCTION

In the 19th century, William Osler, considered the father of modern medicine, extolled the value of patient voice. He liked to say, “He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all.”2 Osler frequently reminded his students to “Listen to your patient, he is telling you the diagnosis.”3 The visionary Thomas Ferguson, MD, recognized in the 1970s the invaluable contribution that empowered and engaged patients could bring to their own health as well as to the system in which they received care.4 And in Reconstructing Illness, Anne Hunsaker Hawkins reminded us that “only when we hear both the doctor's and the patient's voice will we have medicine that is truly human.”5

Given these patient‐centric perspectives expressed by Osler, Ferguson, Hawkins, and surely others over the last 2 centuries, it would seem that the voice of patients would be well integrated into the experience of health and health care. Yet here we are well into the 21st century and only recently have these voices emerged from isolation.

A number of forces have converged in the last decade to ensure patients and caregivers are no longer invisible to the system that was built for them. The most influential force may be the democratization of information and the capacity of real people to create global networks for sharing that has come about as a result of the Internet.

2. BACKGROUND

In 2004, PatientsLikeMe was launched as the direct outcome of one family's experience with a serious life‐changing disease. Inspired by Stephen Heywood's diagnosis with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 1998, his brothers Ben and Jamie and family friend Jeff Cole built a digital platform to collect and aggregate at scale health data directly from patient and caregivers. What has emerged is a research‐based platform for new knowledge derived from shared real‐world experiences and outcomes of patients and caregivers.

Innovative ideas in health and health care are often prompted by the experiences of individuals and those close to them after the diagnosis of a serious illness, while navigating the challenges of diagnostic uncertainty, and/or managing the complexity of decision making and changing care needs over time. PXE International was founded in 1995 to support individuals affected by pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) by parents Sharon and Patrick Terry. Sharon Terry has gone on to lead Genetic Alliance, an organization and biobank that provides advocacy, education, and empowerment support to a large network of disease‐specific organizations. In 1991, actor Michael J. Fox was diagnosed with young onset Parkinson disease and later established a foundation that bears his name to support research of this complex condition. Gilles Frydman expanded a listserv he subscribed to after his wife's diagnosis with breast cancer. In 1995, the listserv became the American Association of Cancer Online Resources, one of the first health‐related social networks that supports the sharing of collective intelligence of patients and caregivers about specific and rare types of cancer. These organizations and many others like them have contributed to the advancement of patient engagement, patient centricity, and advocacy in drug development, research, and care delivery.

PatientsLikeMe sets out to differentiate itself by creating a platform upon which data generated by patients themselves could be systematically collected and quantified while also providing an environment for peer support and networking. Like other patient organizations PatientsLikeMe is governed by a Privacy Policy. However, unlike other organizations, the uniquely disruptive characteristic of PatientsLikeMe is its Openness Policy, which describes the company's belief that when patients share real‐world data for research purposes collaboration and learning on a global scale become possible. Patients and caregivers, no longer dependent on traditional sources of health information and data sharing, can participate in real‐world knowledge translation using person‐centric quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Openness on PatientsLikeMe also means that the health profiles created by members are viewable by other members of the community. The opportunity to view other patients' health profiles remains a truly unique aspect of the PatientsLikeMe member experience.

In collaboration with the world's largest pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, renowned academic centers, professional organizations, and government agencies, PatientsLikeMe has integrated the voice of patients and caregivers into more than 90 open‐access research studies representing previously untapped knowledge sourced directly from person‐reported data. Chronological bibliographies of publications and scientific posters are accessible for download on the PatientsLikeMe Research webpage.6

To date, nearly 500 000 patients and their caregivers have participated in this online research‐based network. They have shared their personal journeys in data‐driven health profiles, narrative journals, and discussion forums about their symptoms, treatments, and other interventions while connecting with and learning from other's in the community.

Much of what has been accomplished at PatientsLikeMe is directly attributable to the courage, curiosity, and selflessness of patients and caregivers willing to share their experiences—without whom new knowledge and continuous learning is just not possible.

3. METHODOLOGY

The hallmark of the PatientsLikeMe data model is its capacity to systematically collect, aggregate, measure, and analyze patient‐generated data at scale using both quantitative and qualitative approaches.7 At the outset, PatientsLikeMe communities were built with condition‐specific boundaries such that a patient with multiple sclerosis was essentially in a “walled garden” with other patients with multiple sclerosis and unable to communicate with a patient who reported a different primary condition. In 2011, the walls between communities were removed allowing anyone to join PatientsLikeMe with any condition.8 While still asked to identify a primary condition, patients can now create health profiles that reflect the full spectrum of their health history in a longitudinal record, and importantly, they can connect with any other member of the PatientsLikeMe community regardless of their identified condition(s).

In the year following these changes in the patient experience and site infrastructure, the PatientsLikeMe team embarked on a company‐wide project to evaluate and improve the site's design, data collection methods, and overall functionality. Led by a specialist in design and user experience, the PatientsLikeMe team created patient‐centric processes and research methods to ensure that patients and caregivers were fully engaged in the project.

3.1. Patient and caregiver interviews

The team developed an interview guide heavily influenced by techniques used in ethnographic interviewing, a qualitative research method that combines immersive observation and directed one‐on‐one conversations.9, 10 The team conducted 60‐ to 90‐minute interviews with patients and/or caregivers in their home environment or via videoconference.

The objectives of the interviews were to learn about how people think, feel, and behave across the experience of illness at different points in time. The concept of being on a “journey” was used to frame the interview along key domains:

Getting diagnosed

Reaction to diagnosis

Adjusting to life

Sources used to get information

Methods used to keep track of information

Tools used for decision making

Sources of support

Personal goals for their health and health care

Biggest questions and concerns experienced along the way

The PatientsLikeMe team was interested in interviewing patients and caregivers with conditions that present with a range of characteristics that might vary across the journey. Some key characteristics of conditions of interest included

Complexity of treatment and care options available

Recency of diagnosis

Speed of progression

Ease of measurement

Availability of treatment

Treatability versus inevitable decline

Existing medical information

Likelihood of stigma

Lifestyle related versus not

The initial cohort of 29 interviewees included 16 who were members of PatientsLikeMe and 13 nonmembers. Twenty‐two interviewees identified themselves as patients; 5 identified as caregivers; and 2 interviewees identified themselves as both a patient and a caregiver. The interviewees represented 17 different primary conditions including ALS, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, diabetes types I and II, breast cancer, lymphoma, chronic leukemia, Crohn disease, cystic fibrosis, autism, epilepsy, hypertension, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Many interviewees reported having more than one health condition. The youngest interviewee was 17 years old, and the oldest was in his 70s.

Three members of the PatientsLikeMe team were assigned to each interview and each had a specific role. The “pilot” led the interview; the “co‐pilot” occasionally engaged and asked clarifying questions; and the “observer” watched the interaction to provide the other team members feedback after the interview. The team members represented different disciplines to ensure a diverse approach to the interview experience. For example, a member of PatientsLikeMe with epilepsy was interviewed at his home by a team that included a nurse, a design and user experience specialist, and a software developer.

The team compiled a large volume of notes and observations from each interview. These were reviewed to identify thematic categories that focused on the events, feelings, and questions that patients and caregivers spoke about as they described their experiences across the various stages of their conditions. A diverse range of events, feelings, and questions emerged naturally using a conversational style of interviewing.

4. RESULTS

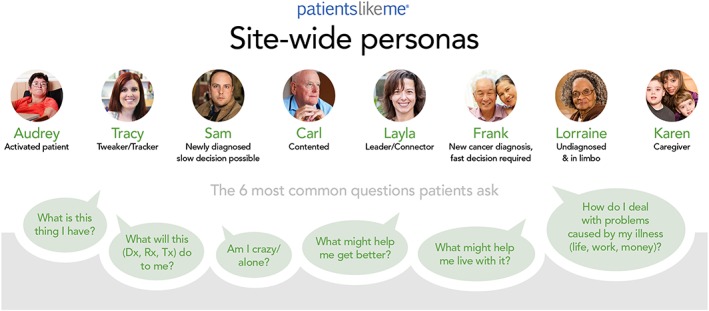

Patients and caregivers spoke candidly about the uncertainty of recognizing that something might be wrong, the fear of hearing a diagnosis, the confusion of treatment decisions, and, for some, the devastation of experiencing a recurrence of their previously treated disease. Yet despite the interviewees' diverse personal situations and health conditions, the analysis of the data illuminated 6 common questions that were asked by most everyone at some point on their journey (Figure 1).

What is this thing I have?

What will this (diagnosis, drug, treatment) do to me?

Am I crazy; am I alone?

What might help me get better?

What might help me live with it?

How do I deal with problems (life, work, family) caused by my illness?

Figure 1.

Six common questions and site‐wide personas

In addition, as the team aggregated the qualitative data, they began the process of developing a group of personas. Personas are commonly used in User Experience design as archetypes that help guide decisions about site features, navigation, interactions, and even visual design.10 The personas created for PatientsLikeMe were synthesized from the team's research and ethnographic interviews to represent the diversity of behaviors, preferences, and characteristics of patients and caregivers (Figure 1).

4.1. A patient and caregiver journey framework emerges

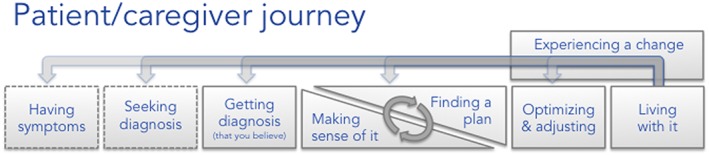

What emerged from the qualitative data were key domains that highlight the different stages that patients and caregivers described as they shared their stories with the PatientsLikeMe team about their experiences living with illness and caregiving across time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stages across a patient and caregiver journey

Stages are influenced by many variables including but not limited to personal situations and the type of health condition. While the stages are depicted along a linear plane, we found that the journey may be a series of steps that can sometimes move forward and at other times backward. Consider a person who is effectively managing her health condition to fit into her life, her work, and relationships only to have an unexpected caregiver role imposed on her—“making sense of it” now requires “finding a plan” to meet the new caregiving responsibilities but may also require her to reoptimize and readjust the management of her health condition due to increased physical and mental demands.

For some conditions, the time spent in any stage of the journey might be relatively short, while in other conditions, the same stage could linger much longer. The diagnosis of a broken leg may take minutes, whereas the diagnostic journey of multiple sclerosis can and often does take years. We heard that a major challenge was the overlap needed to make sense of one's situation (which is often emotional and information overload) while simultaneously they were working on an initial treatment plan. This was particularly challenging in conditions where fast treatment decisions were required, such as in aggressive cancers; the overwhelmed patient and short timeframe appeared to correlate with more reliance on physicians to drive decisions.

4.2. Identifying events, feelings, and questions across the journey

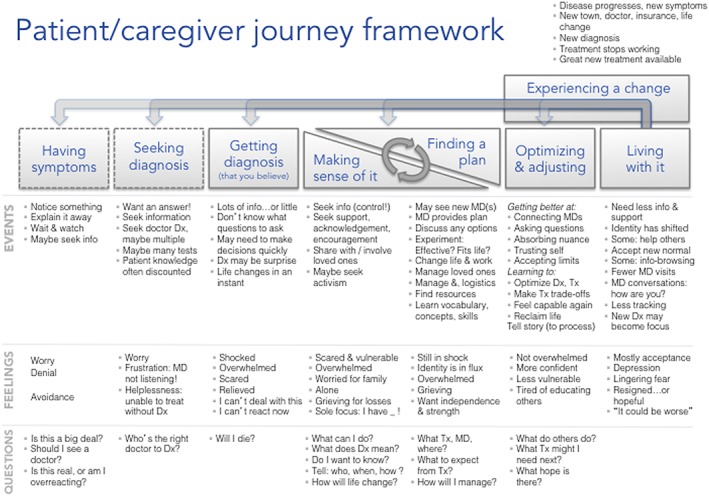

Once the journey stages were articulated, the team began to map the events, feelings, and questions patients and caregivers described in great detail as they talked about their experiences at different times across their journey. The addition of personalized context and emotion to each stage of the journey provides a dimensionality that creates a nuanced and rich framework (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PatientsLikeMe patient and caregiver journey framework

Exploring the multiple dimensions of events, feelings, and questions within the stages across the journey provide a unique lens through which to consider the many layers of complexity that exist for patients and caregivers living with and managing their lives across their journeys. While each person's experiences are uniquely his/her own, the PatientsLikeMe team found remarkable similarities across individuals and conditions.

4.3. Having symptoms

Most of us know our bodies well enough to know when something does not seem quite right. We may experience an event such as a fall that “just happened” for no apparent reason, a momentary blurring of vision that seems to be coming more often, or the unmentionable problem of constipation that just is not responding to the usual tactics. These events can be quite unsettling. Some of us may take a watch and wait approach, others may turn to “Dr. Google,” and some may decide to just explain it away.

During interviews, patients and caregivers described feelings all of us can understand—they were worried, they chose denial rather than confront something that frightened them, or they just avoided the obvious.

One patient who was eventually diagnosed with multiple sclerosis told the team that her boss thought she was drinking while at work. Another patient who went on to get the devastating diagnosis of ALS said, “I would lose control in my hand when I got cold. I thought I was just tired.” Although most of us will not receive a serious and life‐threatening diagnosis when we are experiencing “something that isn't quite right” we can all appreciate the kinds of questions that arise in the presence of uncertainty:

“Is this a big deal?”

“Should I see someone about it?”

“Am I overreacting or is something real going on?”

4.4. Seeking diagnosis

The feelings associated with seeking a diagnosis are often a continuation of those experienced while having symptoms—albeit at a more heightened degree. In addition, patients and caregivers spoke about feeling increasingly frustrated especially when they perceived that the health provider was not listening to them. A sense of helplessness pervaded their thoughts as they grappled with the reality that without a diagnosis, treatment options were elusive.

This stage requires a lot of activity for both patients and caregivers as they navigate the various parts of a complex health care system. They “want an answer” and are seeking out whatever sources of information are available to them. Their search for answers takes time and may involve visits to doctors, sometimes seeing multiple providers and enduring a range of tests and procedures.

As they move through the system, patients and caregivers carry their story with them and may have to retell it many times, as they attempt to find the right kind of provider to give them an answer. One patient said, “I knew I had Parkinson's two years before the neurologist agreed.” Some reported that providers discounted their accumulated knowledge and experience. One mother began to ask herself, “Am I crazy?” after her suspicions of autism were dismissed by the pediatrician for a year. Patients very much want diagnoses because they believe a diagnosis will legitimize what they are experiencing. Several interviewees expressed frustration when the first diagnoses they received did not match their experiences.

4.5. Getting a diagnosis (that you believe)

When patients finally get a diagnosis they believe, it can be a life‐changing moment that stands out in their memories long after. For some, their first question was, “Will I die?” while most of those interviewed said they did not know what questions to ask.

The events and feelings at this stage vary widely by condition type. For someone diagnosed with breast cancer or lymphoma, there are many time‐sensitive decisions that need to be made regarding treatment options. A diagnosis of psoriasis also requires treatment decisions but without the same sense of urgency as a cancer diagnosis.

For many patients, the range of emotions and feelings may vary in intensity and often reflect the severity of the diagnosis. Patient and caregivers report feeling shock, relief, and fear.

BOX 1. Patient comments on getting diagnosis.

“A diagnosis was a relief because it gave me an answer about what was going on in my head. I couldn't trust my own mind.”

‐ on being diagnosed with bipolar disorder

“I thought: I'm getting married. I can't deal with this until after that.”

‐ on delaying her initial multiple sclerosis treatment

Some wonder how they will deal with it—others retreat and opt not to react in the moment. Some spoke about having too much information while others were at the other extreme of getting too little.

4.6. Making sense of it

By this time, patients and caregivers are seeking ways to get some control over situations that may seem out of control. A woman trying to make sense of her bipolar disorder said, “You feel your entire life is out of control. Any positive things to make it seem you're in control…and any things you can do yourself, without help, are empowering.”

Many are actively seeking support, acknowledgement, and encouragement. They may begin to get their loved ones more involved. A few patients became involved in causes associated with their conditions. One mother fully immersed herself in learning as much as possible saying, “I think I got a master's degree in autism that first six months.”

Some interviewees got stuck in this stage and became immobilized by their feelings. Many felt scared and vulnerable, overwhelmed, and alone. For some, their sole focus was, “I have <disease name>!” that made it challenging to shift their thinking to finding a plan. Still others expressed worry about their family and described a sense of grief for the time they might lose, the experiences they might not have, or even for their image of themselves as strong and healthy people.

BOX 2. Making sense of it.

“I wanted information, but slower. A river, not a wave”

‐ on feeling overwhelmed right after diagnosis

“Everything you expected your life to be … you lose that.”

‐ on accepting that her son had autism

4.7. Finding a plan

The activity and events associated with finding a plan are often closely associated with making sense of it. For some, these 2 stages occurred simultaneously. Other patients and caregivers found themselves better able to make sense of it as they began making plans.

During this stage, patients and caregivers are likely to see new doctors and other providers. They are apt to weigh out different options for how their health condition will fit into their lives, especially for family and work. Patients and caregivers are also learning new vocabulary, concepts, and skills that can be both challenging and empowering.

This stage is also a reality check on resources—both human and financial. Patients and caregivers start to assess the impact of the health condition on their daily lives. Conversations emerge about the costs associated with managing care, treatment, appointments, time away from work, and relationships. Most talk about the need for a plan that supports their independence and provides the right balance of support to help them remain strong and in control.

4.8. Optimizing and adjusting

As patients and caregivers talked about moving into this stage, they often described feeling less overwhelmed, more confident. They also talked about growing weary of the need to educate others—including their own families as well as providers and insurers. As they grew more knowledgeable, they reported feeling capable again. Patients begin to see themselves as experts alongside their providers. One parent talked about fighting to get coverage for an uncommon test and treatment for her daughter based on knowledge that she had accumulated about the treatment, “I told them, ‘She is not right. You don't know what [her] normal is.’”

Aspects of this phase may be influenced by condition type. Patients with progressive and life‐threatening conditions began to see their limitations with greater clarity and in some situations with acceptance. Questions tended to become future‐oriented—“What treatment might I need next?” “What hope is there?”

Patients and caregivers found a different voice with which to tell their story. As they began to reclaim their life, their story and its evolution became a way to process their situation. One caregiver summed up her transition from research mode to personalizing her family's journey, “You go from needing to know about autism to needing to know about your child.” While patients and caregivers talked about the power of sharing their emerging story, they were also wondering about the experiences of others by asking, “What do others do?”

Might the very essence of a learning community be the moment when a member of the community embraces the role of both teacher and learner. As more members evolve into those roles, all members of the community, new and seasoned, empower each other to continuously contribute to an ever‐expanding knowledge base.

4.9. Living with it

This is the stage that patients and caregivers describe as their new normal: life might not be the same, but the disease no longer dominates their thoughts. Other aspects of life take their proper place again. The transition from optimization and adjustment to living with it finds patients and caregivers in need of less information and support, in fact, some report they are now helping others. The time spent with health care professionals has decreased while the time spent self‐managing increases. Questions are fewer yet the range of feelings remains mixed, with acceptance mixed with lingering fears and for some depression.

BOX 3. Living with it.

“I'm just grateful for pain‐free days. I try not to think about the past or the future.”

‐ on living with psoriatic arthritis for years

“I used to wake up and think, ‘My God, I have Parkinson's! Now I wake up and think, ‘My God, I have to do the dishes.’”

‐ on contemplating the evolution of her journey with Parkinson's

4.10. Experiencing a change

A change can occur at any point along the journey and that change can significantly impact the patient and caregiver. When we are well, the impact of changes such as moving to a new town, taking a new job, having a baby, or losing a family member can be incredibly challenging. The impact of these changes in the presence of illness and caregiving is amplified.

For patients, a change in physical or mental health condition can bring on a flood of familiar events, feelings, and questions that they thought they had left behind. Consider the impact of disease progression or new symptoms in a person living with relatively stable multiple sclerosis, or the recurrence cancer after remission, or the diagnosis of an entirely new health condition. Alternatively, the change could also be a promising new treatment modality or intervention or the discovery of a personalized and targeted cure. Patients and caregivers may again go through being overwhelmed, seeking information, and finding yet another new normal.

5. DISCUSSION

Although the PatientsLikeMe Patient and Caregiver Journey Framework runs along a linear plane, it is important to remember that the journey for many is punctuated by alternative routes, unexpected detours, and unexplored territory. Every person's journey provides new knowledge, and it is essential to provide those who experienced different paths—either by choice or by happenstance—the opportunity to contribute and share what the insights they have learned—for there is no doubt that one day, someone will take that path again. Two areas of where patient and caregiver perspectives warrant discussion are seeking information and support and learning how to self‐report using their voice and different types of tools.

5.1. On seeking information and support

Many patients and caregivers were interested to know if others shared their experiences and wanted to learn more about what others found helpful. Patients and caregivers identified “experts” they turned to for information. These experts included trusted health care provider if they had one, sought after specialists in their disease if they had a diagnosis, big‐name clinics such as the Mayo and Cleveland Clinics, family and friends—especially those in the health care field, TV personalities such as Dr Oz, known websites such as WebMD, and with less frequency government agencies/websites and drug companies. What all of these sources had in common was the fact that they were already known and trusted, overwhelmed patients and caregivers initially did not seek information from outside of their existing worlds.

Most patients and caregivers reported experiencing very similar feelings that largely differed by degree and severity. The dominant feelings and emotions identified, especially early on in their journey, included grief, isolation, loneliness, feeling overwhelmed, helplessness, and frustration. The first sources of support they sought out were their loved ones. Over time, patients and caregivers came to realize they knew things about their own experiences that doctors and other trusted sources did not. As a result, patients and caregivers started looking for other people “like them” who could provide insights about what it is like to live through and manage the disease itself as well as the symptoms, treatments, and side effects.

For many patients and caregivers, what drove most information and support‐seeking behavior was learning to deal with a new condition and events that changed the status of their condition (ie, a new symptom or the drug they were taking stopped working). Not surprisingly, people were far less likely to seek information and support once they felt they had mastered the management of their conditions.

Some patients and caregivers were more interested in finding information than getting support. One interviewee who is also a member of PatientsLikeMe said she browsed the site to learn about new research but rarely engaged with others said, “I don't want to be friends.” Another member of PatientsLikeMe who focused more on support reported, “It makes me feel like there's someone out there.” Yet connecting with other patients for information and support is not for everyone. Some felt that they would rather not focus on being sick. One interviewee said, “I want to hang around with people I like, not people who have Parkinson's.”

Patients want others to understand their conditions, but may not have the energy to educate others while dealing with new issues themselves. A patient who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis only 2 months prior to the interview said, “I want a sign on my forehead: ‘I'm not drunk, I have MS.’” For another patient with bipolar disorder, teaching her family was a challenge, “Family took a while. I had to train my family how to deal with me. It was hard not to feel judged.” As they mastered their conditions, many patients and caregivers become more interested in teaching others like themselves. As many interviewees told us, this is a way to take back some control and also feel like something good has come from a difficult experience.

BOX 4. Patient comments on tips received from other patients.

“Buy a satin pillowcase for when your hair falls out. Don't bring your grandmother's afghan to chemo, you'll never want to see it again.”

‐ on things learned from cancer survivors

“Somebody said to chew gum so you remember to swallow.”

‐ on the useful tip he got from other patients with Parkinson's Disease

5.2. On creating self‐reports and useful tools

Patients may use different words and have different purposes for creating information about their experiences and capturing that information is useful ways. For the most part, people create 4 types of content about themselves.

-

Tracking how (or what) I'm doing

Patient J monitored her good and bad days looking for trends; Patient L tracked her injection sites as part of her treatment routine; and Patient M jotted down the foods she ate as part of a new contest at her gym.

Tracking tends to fit into a routine such as taking meds with morning breakfast or checking in on PatientsLikeMe after emails have been read.

Most tracking was a short‐term problem‐solving behavior, focused on correlations: “How does this thing I'm doing affect that outcome?” Generally, we saw patients stop tracking in detail after a month or two, as they found answers. Some patients, like Patient D, used tracking to better communicate with health providers. “It opens the door for conversation, because you forget things.”

Tracking also provided visual proof of progress. As one caregiver said of her child with autism, “Sometime I have to sit back & remember how far he's come. Every kid is different, so I don't compare him to others.” Conversely, some patients with progressive conditions found it depressing to track.

-

Keeping my history

The most frequent reason given for keeping a history was to ensure doctors have correct and complete information, especially for people who saw multiple providers. “Having a timeline helps when you go to a new doctor and they throw ten pieces of paper at you.” Some interviewees described thorough note taking as a form of self‐defense.

The second priority reason for keeping one's history is to capture the record of a life‐changing event. “This was hard, so I want a record of it.”

-

Taking notes

Many patients reported taking notes to manage tasks and information when overwhelmed, as they often did during provider visits (especially early in their diagnosis and treatment journeys).

Note taking usually took place at the hospital or health provider's office.

Patients often sought out a family member or friend to help them. Patient K said, “My notebook comes to every doctor's appointment. I sometimes have my husband write so I can just take in what the doctor is saying. Sometimes I have the doctor write something in it too.”

-

Finding a channel for my story

Increasingly people were using social media such as Facebook to keep in touch with family and friends.

Some patients wanted to process their own experiences, and for some, writing, sharing, and conversation were concrete ways of helping others.

Some patients found this useful for a time and then found themselves sharing their story less. Patient M told us, “I don't write so much anymore, I guess I don't have as much to say.”

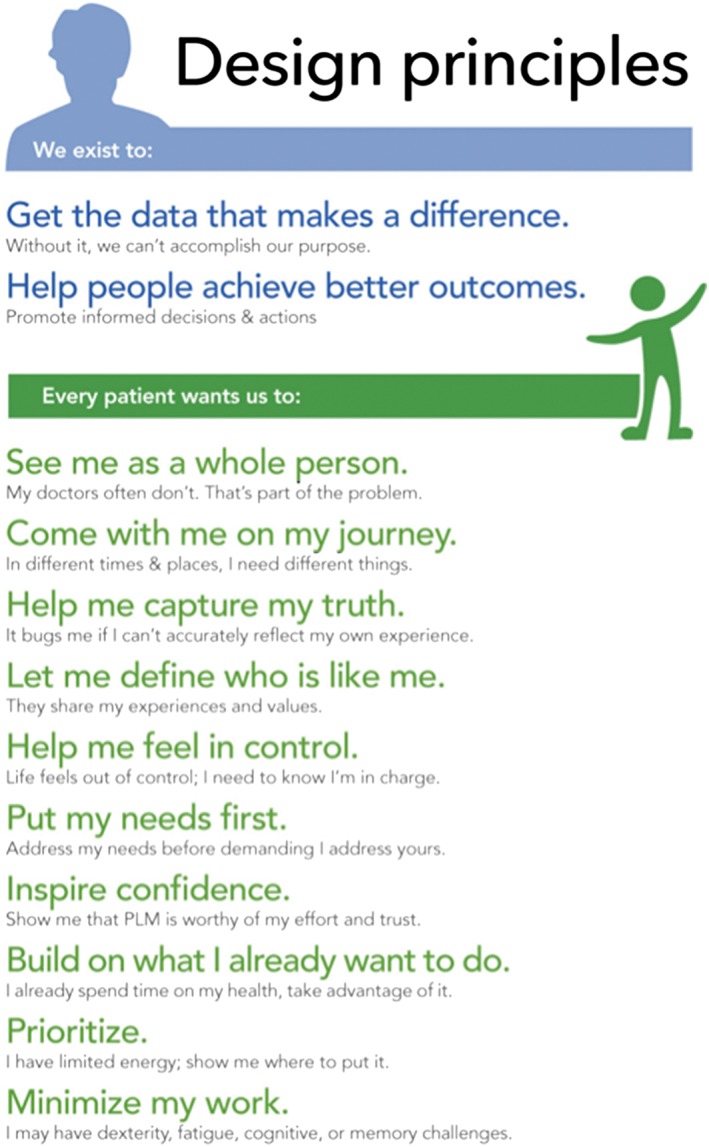

To date well over 100 patient and caregiver interviews have contributed new knowledge and insights to the evolution of the PatientsLikeMe Patient and Caregiver Journey framework. In addition, the findings from these and other interviews have been used in the development of patient‐informed tools including principles that guide the design (Figure 4).of the site and the development of measurement tools (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Patient‐informed design principles

Figure 5.

Patient‐informed measurement principles

6. CONCLUSION

The National Academy of Medicine convened its first workshop on a learning health care system in 2006. In 2012, it published Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. In it, a learning health care system is defined as “one in which science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the care process, patients and families as active participants in all elements, and new knowledge captured as an integral by‐product of the care experience.”11 That same year, the first Learning Health System Summit was convened and created core values for a national‐scale person‐centered, continuous learning health system.12 PatientsLikeMe, a participant in the development of these core values and one of the first organizations to endorse them, was an active participant in the first and later the second Learning Health System Summit that was convened in 2016.

Building a learning health system is a daunting task especially given the fragmentation and complexities of the US health care ecosystem. PatientsLikeMe has focused on contributing to the learning health system by building a learning health community of patients and caregivers. This community is underscored by science, informatics, and a patient‐centric culture where patients and caregivers are not only active participants but also more importantly are active teachers of new knowledge captured as an integral part of the community's shared experiences.

PatientsLikeMe has been advancing the science of patient and caregiver input for over a decade through the use of participatory research techniques, observational methods, and ethnographic interviews that are now well integrated into our community. The team continues to explore complex and life‐changing diseases with patients and caregivers providing a unique lens to view their lived experiences with a host of conditions across different therapeutic areas and rare disorders.

6.1. Balancing challenges and opportunities

Yet the use of qualitative and ethnographic methods is time‐consuming and labor‐intensive. Taking on the task of learning directly from the knowledge and experience of real people living with and managing their health conditions in the real world is a true privilege; however, to be successful it requires multidisciplinary resources and commitments from nearly all levels of the organization. As the PatientsLikeMe team became more well versed and skilled in the techniques and methods described in this experience report greater efficiency and maximum organizational impact started to be realized

In an effort to maximize the efficiency of collecting patient input, the PatientsLikeMe research scientists explored ideas for gathering patient‐informed research priorities similar to the process used by the Patient‐Centered Research Institute to collect research questions of interest directly from patients via PCORI's website.13 The PatientsLikeMe researchers decided to add 2 questions to the end of research surveys seeking input from the survey participants on the value of the research they just participated in and to learn about areas of research of interest to them (Box 5). To date, patients have provided over 7500 Likert scale responses and nearly 4900 narrative responses across 15 separate research projects. The analysis of this ever‐growing data repository remains a work in progress.

BOX 5. Patient‐informed importance of research topics.

- How important are the topics covered in this survey to you?

- Not important at all

- Of little importance

- Of average importance

- Very important

- Extremely important

If you had a single question you wanted researchers to study about your health, what would it be?

The Patient and Caregiver Journey framework has proven to be a repeatable and continuously learning model at PatientsLikeMe. The knowledge and insights derived from this work are not likely unique to the patients and caregivers interviewed by the PatientsLikeMe team. In fact, the 6 common questions, the journey framework, and the patient‐informed principles discussed herein may have relevance across different settings to gather meaningful patient and caregiver experience data and are shared to encourage utilization.

Okun S, Goodwin K. Building a learning health community: By the people, for the people. Learn Health Sys. 2017;1:e10028 10.1002/lrh2.10028

REFERENCES

- 1. Baker MG, Graham L. The journey: Parkinson's disease. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2004;329(7466):611‐614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bean WB. Men and books: Sir William Osler. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1959;104(4):673 10.1001/archinte.1959.00270100159028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Osler Symposium . http://www.oslersymposia.org/about‐Sir‐William‐Osler.html. Last accessed January 29, 2017.

- 4. Thomas K. Tom Ferguson: Publisher of the magazine medical self‐care. Retrieved from at http://www.motherearthnews.com/natural‐health/tom‐ferguson‐zmaz78mjzgoe.aspx. (1978, May/June). Last accessed January 29. 2017.

- 5. Hawkins AH. Reconstructing illness: studies in pathography. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6. A chronological bibliography of PatientsLikeMe: the complete collection of PatientsLikeMe publications. http://news.patientslikeme.com/research. Last accessed January 29, 2017.

- 7. Tempini N. Governing social media: organising information production and sociality through open, distributed and data‐based systems. PhD thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) (2014).

- 8. Gupta S, Riis J. PatientsLikeMe: An Online Community of Patients, HBS No. 9‐511‐093. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spradley JP. The Ethnographic Interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodwin K. Designing for the Digital Age: How to Create Human‐Centered Products and Services. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11. NAM (National Academy of Medicine) . Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academic s Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Learning health community core values. http://www.learninghealth.org/corevalues/. Last accessed April 23, 2017

- 13. Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. http://www.pcori.org/get‐involved/suggest‐patient‐centered‐research‐question. Last accessed May 3, 2017.