Abstract

Background:

The impact of cancer or its treatment on employment and financial burden in adolescents/young adults (AYA) are not fully known.

Methods:

Eligibility for this cross-sectional study of AYA cancer survivors included diagnosis of malignancy between ages 18–39, 1–5 years from diagnosis and ≥1 year from therapy completion. Participants were randomly selected from tumor registries of 7 participating sites and completed an online patient reported outcomes (PRO) survey to assess employment and financial concerns. Treatment data were abstracted from medical records. Data were analyzed across diagnoses and by tumor site using logistic regression, and Wald-based 95% confidence intervals (CI) adjusting for age (categorized), gender, insurance status, education (categorized) and treatment exposures.

Results:

Participants included 872 survivors (breast=241, thyroid=126, leukemia/lymphoma=163, other=342). Exposure to chemotherapy in breast cancer was associated with an increase in self-reported mental impairment in work tasks (OR 2.66) and taking unpaid time off (OR 2.62); in ‘other’ cancer survivors an increase in mental impairment of work tasks (OR 3.67) and borrowing >$10,000 (OR 3.43). Radiation exposure was associated with an increase of mental impairment in work tasks (OR 2.05) in breast cancer, taking extended paid time off work in thyroid cancer (OR 5.05) and physical impairment in work tasks in ‘other’ survivors (OR 3.11). Finally, in ‘other’ survivors, having had surgery was associated with an increase of physical (OR 3.11) and mental impairment (OR 2.31) of work tasks.

Conclusions:

Cancer treatment has a significant impact on AYA survivors’ physical and mental work capacity and time off from work.

Keywords: Adolescent/Young Adult, Cancer, Survivorship, Finances, Employment

Condensed Abstract:

We performed a multi-center, cross-sectional study of AYA cancer survivors between ages 18–39, 1–5 years from diagnosis and >1 year from therapy completion and evaluated the association of treatment related factors with the likelihood of physical and mental impairment of work tasks, as well as the likelihood of changes in employment including any time off from work. Cancer treatment has significant financial and employment implications as well as impact on AYA survivors’ physical and mental work capacity.

BACKGROUND

The incidence of cancer in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15 to 39 years has steadily increased over the past 25 years, and cancer remains a leading cause of non-accidental death in this age group 1. Despite advances in cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment over the past several decades, survival rates for AYAs have not improved to the extent they have for younger children or older adult cancer populations 2,3. AYA survival is often accompanied by ongoing physical, mental, social and emotional challenges such as physical impairment, infertility, uncertainty, fear of recurrence, interruption of life plans, and discrimination in employment and insurance 4,5.

AYAs with a history of cancer are more likely to not be working due to illness as compared to controls 6. AYA survivors who had pursued careers involving physical abilities before cancer diagnosis often believe that they need to adjust their goals as a result of their cancer 7. In addition, AYAs have higher direct annual medical costs ($7417 vs $4247 for adults without a cancer history), experience annual average lost productivity costs due to illness/disability of $2200 per year, and have lower family incomes compared with similar-age adults without cancer 6. These disparate outcomes in the AYA population are likely related to the distinctive disruptions and challenges related to education, employment, physical limitations, identity, relationships and family experienced by the AYA survivor population.

The LIVESTRONG (LS) Foundation developed the Survey for People Affected by Cancer to ascertain how cancer has impacted the life of cancer survivors. To develop this survey, LS coordinated with National Cancer Institute (NCI), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), Center for Disease Control (CDC), American Cancer Society (ACS), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to include elements of the Experiences with Cancer Survivorship supplement of the Medical Expenditures Panel Surveyd 8. More information about the survey can be found on the LS Foundation’s website (https://www.livestrong.org/what-we-do/our-research) and related publications on the population of the original LS survey 9,10.

To address the gap in knowledge regarding the long-term and late effects of cancer specifically in the AYA population, we used the LIVESTRONG Survey, paired with treatment data abstracted from medical records at seven national comprehensive cancer centers that were members of the LS Survivorship Centers of Excellence Network (SCOEN). The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of cancer-directed treatment on physical and mental impairment of work-related tasks, the need for employment changes including paid or unpaid time off from work, and the financial toxicity for cancer survivors aged 18–39 and their families.

METHODS

Recruitment, Study Setting and Participants

This multi-center, cross-sectional study of AYA cancer survivors was conducted through the SCOEN, which is composed of 7 geographically diverse sites, including the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (coordinating center) in Seattle, Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California in Los Angeles, University of Colorado Cancer Center in Denver, and the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Human investigations were performed after approval by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center institutional review board. Eligibility for study participation included a diagnosis of malignancy between ages 18–39 years and survey completion within 1–5 years from diagnosis and >1 year from therapy completion. Participants were sent a recruitment letter and brochure; if participants did not respond, they were sent a second recruitment letter 7–10 days after the initial letter and were called up to 3 times with up to 3 voice mail contacts or voice messages attempted. Those participants who agreed to participate were then sent an email link to complete the study registration online. Once registered to participate, enrolled participants were subsequently sent an email with a link containing a unique URL for the study informed consent and survey.

Assessment of Physical, Mental and Financial Effects

Participants were asked to complete an online survey of patient reported outcomes (PRO). Questions from the PRO related to physical and mental impairment of work-related tasks, extended paid or unpaid time off from work, and cancer survivors or their families borrowing money or going into debt. Questions were also asked about highest level of education achieved and insurance status. For the present investigation, we focused on responses to the following subset of questions: (1) Did you ever feel that your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment interfered with your ability to perform any physical tasks required by your job? (2) Did you ever feel that your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment interfered with your ability to perform any mental tasks required by your job? (3) At any time since your first cancer diagnosis, did you take extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or make a change in your hours, duties or employment status? (4) Did you ever take extended paid time off work (vacation, sick time and/or disability leave)? (5) Did you ever take unpaid time off from work? and (6) How much did you or your family borrow, or how much debt did you incur because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment? Response options varied from < $10,000 to $100,000 or more.

Treatment Exposures

Treatment data were abstracted from medical records using a standardized protocol and entered into a centralized secured online Survivorship Informatics Management System (SIMS) which permitted single data entry, largely from menus with pick-lists, to maintain consistently coded, high quality data with minimal missing data for key variables. Treatment data included information regarding surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation.

Covariates

Potential confounders of the associations between cancer-directed treatment exposure and physical, mental and financial outcomes were selected a priori, based on literature review, and included gender and age at diagnosis (categorized as 18–24, 25–35, or >35 years of age), health insurance coverage, and education (categorized as high school or less, some college/associates degree, college graduate, or postgraduate work).

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed separately by tumor site, including: 1) breast, 2) thyroid, 3) leukemia and lymphoma, 4) and all other cancer sites. Within each tumor site, the PROs were analyzed using logistic regression; Wald based 95% confidence intervals (CI) were generated for all associations. Analyses of each cancer-directed treatment exposure (surgery vs. no surgery, chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy, radiation vs. no radiation) were controlled for age (by category), education (by category), insurance status and gender, with the exception of breast cancer-specific analyses which were all female. Breast cancer survivors were analyzed for combined exposure of chemotherapy and radiation vs. only chemotherapy vs only radiation controlled for age, insurance status, and education (by category). Leukemia and lymphoma survivors were evaluated for combined exposure of radiation and surgery vs. only radiation vs only surgery controlled for age, gender, insurance status, and education (by category). Due to heterogenetity in the group who had a caner other than breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma or thyroid cancer analyses of multiple combinations of treatment factors were not performed. When >90% of participants received treatment with surgery or chemotherapy, analyses did not include that treatment in the controlled variables. Greater than 95% of breast cancer survivors underwent surgery as part of their treatment course; therefore, analyses among breast cancer survivors were controlled for treatment exposures other than surgery (chemotherapy or radiation). Similarly, greater than 90% of leukemia and lymphoma survivors were exposed to chemotherapy and, therefore, analyses within this survivor population were adjusted for radiation or surgery, but not for chemotherapy. Analyses were limited to enrolled study participants who completed the PRO survey. All analyses were performed in R studio version 1.0.153 11.

RESULTS

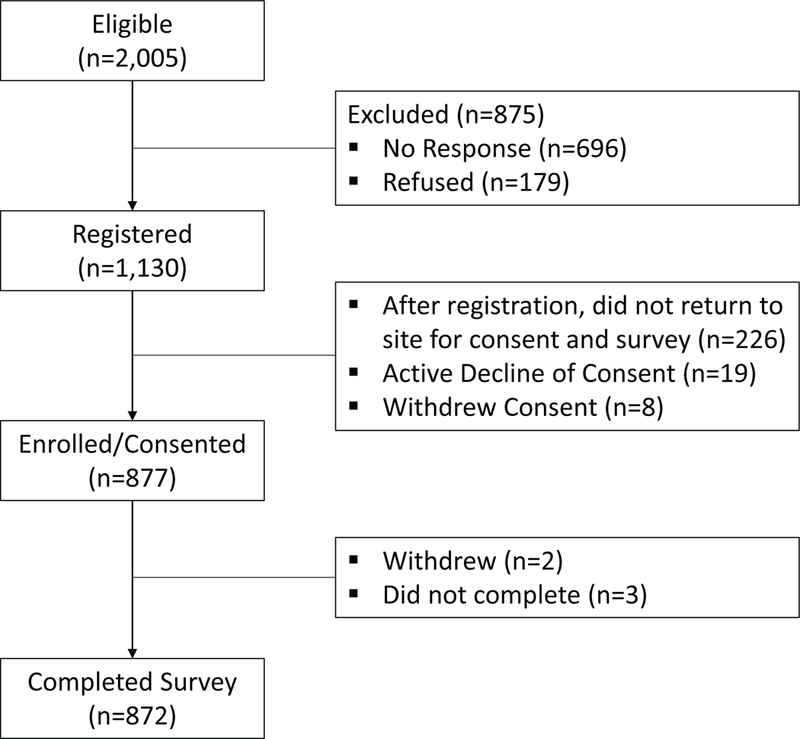

The study initially identified participants from 7 different participating study sites from site tumor registries or patient schedules for follow-up. From medical record screening, N=2005 were determined to be eligible for approach. Of those, 1309 (65.3%) were successfully contacted and 56.4% (N=1130) patients registered for the study providing permission to receive the the study survey link electronically or by mail if requested (N=14). In response to the study email with survey link (or to the mailed survey and consent), 877 patients (67% of those contacted) consented and N=872 completed the survey (Figure 1). Passive refusal and/or incorrect contact information was noted for 34.7% of potentially eligible survivors and there were no tracing efforts of those cases. Of the participants who completed the PRO survey, 635 (72.8%) participants were female and 237 (27.2%) were male, with a median age at diagnosis of 32.3 and 29.8 years respectively and a mean of 3.53 and 3.40 years from diagnosis respectively; 80.6% of participants were white (Table 1). In addition to all but one breast cancer participant being female (N=240), a majority of endocrine (predominantly thyroid) and skin cancer (predominantly melanoma) participants were female (84.4% and 74.4% respective) consistent with sex proportion of those diagnosed 12.

Figure 1:

CONSORT flow diagram of study participation.

Table 1:

Characteristics of young adult survivors by gender

| Female | Male | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 635 | 237 | |||

| Age at Diagnosis (mean (sd)) | 32.3 (5.62) | 29.8 (6.09) | |||

| Age Category at Diagnosis (n (%)) | |||||

| 18–24 | 84 (13.2) | 55 (23.2) | |||

| 25–34 | 306 (48.2) | 122 (51.5) | |||

| 35–39 | 245 (38.6) | 60 (25.3) | |||

| Years from Diagnosis (mean (sd)) | 3.53 (1.49) | 3.40 (1.29) | |||

| EthnicityDesc (%) | |||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 577 (90.9) | 212 (89.5) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 49 (7.7) | 23 (9.7) | |||

| Declined/Unknown | 9 (1.4) | 2 (0.8) | |||

| Race (%) | |||||

| White | 504 (79.4) | 199 (84.0) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 57 (9.0) | 21 (8.9) | |||

| Black | 43 (6.8) | 6 (2.5) | |||

| Deferred/NA | 31 (4.9) | 11 (4.6) | |||

| Education (%) | |||||

| High School or Less | 41 (6.5) | 17 (7.2) | |||

| Some College/Associates Degree | 126 (19.8) | 59 (24.9) | |||

| College Graduate | 231 (36.4) | 89 (37.6) | |||

| Postgraduate Work | 215 (33.9) | 64 (27.7) | |||

| Insurance Coverage (%) | 605 (95.3) | 219 (92.4) | |||

| Diagnosis (%) | |||||

| Breast | 240 (37.8) | 1 (0.4) | |||

| Leukemia & Lymphoma | 83 (13.1) | 80 (33.8) | |||

| Endocrine system † | 108 (17.0) | 20 (8.4) | |||

| Skin | 60 (9.4) | 21 (8.9) | |||

| Genital system - Female ‡ | 49 (7.7) | 0 (0) | |||

| Genital system - Male § | 0 (0.0) | 46 (19.4) | |||

| Brain & other nervous system | 24 (3.8) | 17 (7.2) | |||

| Bones & Soft Tissue | 17 (2.7) | 19 (8.0) | |||

| Digestive system ¶ | 24 (3.8) | 11 (4.6) | |||

| Oral cavity & pharynx | 13 (2.0) | 12 (5.1) | |||

| Urinary system †† | 8 (1.3) | 6 (2.5) | |||

| Other | 10 (1.6) | 3 (1.3) | |||

Endocrine system = thyroid, adrenal, other endocrine.

Genital system - Female = uterine cervix, uterine corpus, vagina, vulva, other female.

Genital system - Male = prostate, testis, penis, other male genital.

Digestive system = esophagus, small intestine, colon, rectum, anus, anal canal, analrectum, liver, intrahepatic biliary duct, hepatoblastoma, gallbladder, biliary system, pancreas, other digestive organs.

Urinary system = Urinary bladder, kidney, renal pelvis, ureter, wilms tumor, other urinary organs

Overall, 84.4% (N=736) of participants were employed at some time from diagnosis with cancer until study participation. Among participants who reported working, 70.2% (N=517) reported a physical component required by their job and 58.6% (N=303) reported their cancer, its treatment or the lasting effect of treatment interfered with physical tasks required by their job. Of participants who were working, 54.2% (N=399) reported that their cancer, its treatment or the lasting effects of treatment interfered with their ability to perform mental tasks required by their job. Among AYA survivors who were working and reported physical tasks associated with their jobs, those exposed to chemotherapy were significantly more likely to report interference with physical tasks required by their job (OR 1.97, CI 1.22–311, p<0.01), compared to survivors who did not receive chemotherapy, adjusting for radiation and surgery exposure, as well as age at diagnosis and gender (Table 2). Receipt of chemotherapy was also significantly associated with reported interference with mental tasks required by a job (OR 3.22, CI 2.15–4.79, p<0.01) and any time off from work (3.56, CI 2.31–5.47, p<0.01). With the exception of the association between radiation and interference with physical tasks at work, radiation and surgery associations were not statistically significant (Table 2). Across diagnoses, 14.4% (N=126) of AYA survivors reported their families borrowed $10,000 or more. Those who were exposed to chemotherapy were significantly more likely to report that they or their families borrowed greater than $10,000 (OR 3.05, CI 1.53–6.09, p<0.01) compared to survivors not exposed to chemotherapy within the same gender, age (categorical), education (categorical), insurance status, radiation and surgery exposure. A total of 1.5% (N=13) of AYA survivors reported that they or their family had filed for bankruptcy because of their cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment. Due to the infrequent rate of this outcome, we did not evaluate associations with treatment modalities.

Table 2:

Association of cancer directed treatment factors and physical and mental impairment at work, and change in employment among young adult cancer survivors working at any time from diagnosis to study participation.

| Chemotherapy † | Radiation ‡ | Surgery § | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n Chemotherapy/ n no Chemotherapy (%) | OR | 95% CI | n Radiation/ n no Radiation (%) | OR | 95% CI | n Surgery/ n no Surgery (%) | OR | 95% CI | ||||||||||||||

| Interfered with physical tasks required by job | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 96 / 119 (44.7) | 1.00 | Ref | 80 / 135 (37.2) | 1.00 | Ref | 172 / 43 (80.0) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 187 / 115 (61.9) | 1.97 | (1.22–3.11) | ** | 140 / 162 (46.4) | 1.66 | (1.08–2.41) | * | 240 / 62 (79.5) | 1.57 | (0.90–2.73) | |||||||||||

| Interfered with mental tasks required by job | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 144 / 189 (43.2) | 1.00 | Ref | 122 / 211 (36.6) | 1.00 | Ref | 264 / 69 (79.3) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 269 / 130 (67.4) | 3.22 | (2.15–4.79) | ** | 182 / 217 (45.6) | 1.39 | (0.99–1.94) | 321 / 78 (80.5) | 1.46 | (0.90–2.35) | ||||||||||||

| Extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or a change in your hours, duties or employment status | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 64 / 108 (37.2) | 1.00 | Ref | 63 / 109 (36.6) | 1.00 | Ref | 137 / 35 (79.7) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 352 / 212 (62.4) | 3.56 | (2.31–5.47) | ** | 243 / 321 (43.1) | 1.07 | (0.73–1.58) | 452 / 112 (80.1) | 1.21 | (0.71–2.08) | ||||||||||||

| Extended paid time off from work | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 115 / 63 (64.6) | 1.00 | Ref | 77 / 101 (43.3) | 1.00 | Ref | 143 / 35 (80.3) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 228 / 138 (62.3) | 1.02 | (0.62–1.67) | 165 / 201 (45.1) | 1.03 | (0.69–1.55) | 293 / 73 (80.1) | 0.54 | (0.54–1.00) | * | ||||||||||||

| Unpaid time off from work | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 159 / 96 (62.4) | 1.00 | Ref | 119 / 136 (46.7) | 1.00 | Ref | 199 / 56 (78.0) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 183 / 103 (64.0) | 1.39 | (0.79–2.36) | 122 / 164 (42.7) | 0.90 | (0.62–1.32) | 234 / 52 (81.8) | 1.37 | (0.79–2.36) | |||||||||||||

Adjusted for diagnosis (categorical), age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, radiation status, and surgery status.

Adjusted for diagnosis (categorical), age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, chemotherpy status, and surgery status.

Adjusted for diagnosis (categorical), age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, chemotherapy status, and radiation status.

p-value <0.05

p-value <0.01

Breast Cancer

In total, 241 participants who completed the PRO survey had a diagnosis of breast cancer, of whom 86.7% (N=209) were employed at some time from diagnosis with cancer until study participation. Among survivors who were working, those who were exposed to chemotherapy were significantly more likely to report interference with mental tasks required by their job (OR 2.66, CI 1.32–5.34, p<0.01) and take unpaid time off from work (OR 2.62, CI 1.09–6.30, p<0.05) compared to those not exposed to chemotherapy (Table 3). Also, those exposed to radiation were significantly more likely to report interference with mental tasks required by their job (OR 2.05, CI 1.11–3.78, p<0.05) compared to those not exposed to radiation. We did not find an association with cancer-directed treatment exposure and the ability to perform physical tasks required by a job, nor was there an association between cancer-directed treatment exposure and AYA breast survivors or their families borrowing greater than $10,000. Among breast cancer survivors who were working with the same age, education and insurance status, those who received chemotherapy were more likely to take extended paid time off work compared to those received both chemotherapy and radiation (OR 3.08 CI 1.18–8.03, p=0.02). Those who received chemotherapy and radiation were also more likely to have advanced disease.

Table 3:

Association of cancer directed treatment factors and physical and mental impairment at work, and change in employment among young adult breast cancer survivors working at any time from diagnosis to study participation.

| Chemotherapy † | Radiation ‡ | ||||||||||||||

| n Chemotherapy/ n no Chemotherapy (%) |

OR | 95% CI | n Radiation/ n no Radiation (%) |

OR | 95% CI | ||||||||||

| Interfered with physical tasks required by job | |||||||||||||||

| No | 42 / 17 (71.2) | 1.00 | Ref | 33 / 26 (55.9) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||

| Yes | 66 / 13 (83.5) | 2.03 | (0.82–5.01) | 47 / 32 (59.5) | 1.11 | (0.53–2.33) | |||||||||

| Interfered with mental tasks required by job | |||||||||||||||

| No | 57 / 33 (63.3) | 1.00 | Ref | 41 / 49 (45.6) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||

| Yes | 100 / 18 (84.7) | 2.66 | (1.32–5.34) | ** | 77 / 41 (65.3) | 2.05 | (1.11–3.78) | * | |||||||

| Extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or a change in your hours, duties or employment status | |||||||||||||||

| No | 29 / 13 (69.0) | 1.00 | Ref | 27 / 15 (64.3) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||

| Yes | 129 / 38 (77.2) | 1.76 | (0.78–3.99) | 91 / 76 (54.5) | 0.62 | (0.29–1.33) | |||||||||

| Extended paid time off from work | |||||||||||||||

| No | 38 / 8 (82.6) | 1.00 | Ref | 36 / 10 (78.3) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||

| Yes | 88 / 28 (75.9) | 1.10 | (0.42–2.91) | 55 / 61 (47.4) | 0.25 | (0.10–0.62) | ** | ||||||||

| Unpaid time off from work | |||||||||||||||

| No | 60 / 25 (70.6) | 1.00 | Ref | 44 / 41 (51.8) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||||||

| Yes | 65 / 11 (85.5) | 2.62 | (1.09–6.30) | * | 46 / 30 (60.5) | 1.14 | (0.57–2.28) | ||||||||

Adjusted for age (categorical), education (categorical), insurance, and radiation status.

Adjusted for age (categorical), education (categorical), insurance, and chemotherapy status.

p-value <0.05

p-value <0.01

Leukemia and Lymphoma

Of the 163 survey participants who had a diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma, 79.8 (N=130) were employed at some time from diagnosis with cancer until study participation. As noted above, nearly all of these participants received chemotherapy (90%). No further association was found between cancer-directed treatment exposure to surgery or radiation and interference with physical or mental task required by their job among working leukemia and lymphoma survivors (Table 4). In this group, there was no association between cancer-directed radiation or surgery exposures and paid time or unpaid time off from work nor was there an association between cancer-directed treatment exposure and AYA leukemia and lymphoma survivors or their families borrowing greater than $10,000. Analyses were performed for joint associations between treatment exposures including surgery and radiation in the leukemia and lymphoma group and no statistically significant associations were found.

Table 4:

Association of cancer directed treatment exposures of radiaiton or surgery and physical and mental impairment at work, and change in employment among young adult survivors of leukemia or lymphoma working at any time from diagnosis to study participation (all received chemotherapy).

| Radiation † | Surgery ‡ | |||||||||||||||

| n Radiation/ n no Radiation (%) |

OR | 95% CI | n Surgery/ n no Surgery (%) |

OR | 95% CI | |||||||||||

| Interfered with physical tasks required by job | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 13 / 13 (50.0) | 1.00 | Ref | 6 / 20 (23.1) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||

| Yes | 27 / 29 (48.2) | 1.01 | (0.34–2.94) | 20 / 36 (35.7) | 1.63 | (0.49–5.44) | ||||||||||

| Interfered with mental tasks required by job | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 25 / 26 (49.0) | 1.00 | Ref | 15 / 36 (29.4) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||

| Yes | 29 / 49 (37.2) | 0.68 | (0.32–1.45) | 25 / 53 (32.1) | 1.11 | (0.47–2.62) | ||||||||||

| Extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or a change in your hours, duties or employment status | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 12 / 12 (50.0) | 1.00 | Ref | 7 / 17 (29.2) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||

| Yes | 43 / 63 (40.6) | 0.61 | (0.23–1.58) | 34 / 72 (32.1) | 0.77 | (0.25–2.39) | ||||||||||

| Extended paid time off from work | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 13 / 31 (29.5) | 1.00 | Ref | 18 / 26 (40.9) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||

| Yes | 29 / 30 (49.2) | 2.50 | (0.98–6.39) | 15 / 44 (25.4) | 0.42 | (0.15–1.20) | ||||||||||

| Unpaid time off from work | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 25 / 28 (47.2) | 1.00 | Ref | 14 / 39 (26.4) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||

| Yes | 17 / 33 (34.0) | 0.54 | (0.22–1.31) | 19 / 31 (38.0) | 1.54 | (0.59–4.02) | ||||||||||

Adjusted for age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, and surgery status.

Adjusted for age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, and radiation status.

p-value <0.05

p-value <0.01

Thyroid Cancer

All but 2 endocrine cancers were diagnosed as thyroid, therefore analyses included in analyses only the 126 with thyroid cancer. Of those participants, 82.5% (N=104) were employed at some time from diagnosis with cancer until study participation. No association was found between cancer-directed treatment exposures and interference with physical or mental tasks required by their job in patients in thyroid cancer survivors (Table 5). Among thyroid cancer survivors who were working, those survivors exposed to radiation were significantly more likely to report taking extended paid time off from work (OR 5.05, CI 1.36–18.73, P<0.05) than those who were not exposed to radiation. There was no association between cancer-directed treatment exposures and interference with paid or unpaid time off from work, nor was there an association between cancer-directed treatment exposure and AYA thyroid survivors or their families borrowing greater than $10,000.

Table 5:

Association of cancer directed radiation and physical and mental impairment at work, and change in employment among young adults survivors of thyroid cancer working at any time from diagnosis to study participation.

| Radiation † | ||||||||

| n Radiation/ n no Radiation (%) |

OR | 95% CI | ||||||

| Interfered with physical tasks required by job | ||||||||

| No | 20 / 21 (48.8) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 21 / 12 (63.6) | 2.16 | (0.70–6.62) | |||||

| Interfered with mental tasks required by job | ||||||||

| No | 28 / 27 (50.9) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 29 / 20 (59.2) | 1.69 | (0.72–3.96) | |||||

| Extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or a change in your hours, duties or employment status | ||||||||

| No | 14 / 15 (48.3) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 43 / 32 (57.3) | 1.51 | (0.59–3.83) | |||||

| Extended paid time off from work | ||||||||

| No | 8 / 13 (38.1) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 35 / 15 (70.0) | 5.05 | (1.36–18.73) | * | ||||

| Unpaid time off from work | ||||||||

| No | 22 / 15 (59.5) | 1.00 | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 21 / 13 (61.8) | 1.11 | (0.31–3.95) | |||||

Adjusted for age (categorial), gender, education (categorical), and insurance.

p-value <0.05

p-value <0.01

Chemotherapy is not standard for thyroid cancer treatment and nearly all had surgery.

Other Cancers

The remaining 328 participants who completed the PRO survey had a diagnosis other than breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma or thyroid cancer, including sarcoma, germ cell tumors, skin cancer and brain tumors. Of these 281 (85.7%) were employed at some time from diagnosis with cancer until study participation. Among survivors who were working, those who were exposed to chemotherapy were significantly more likely to report interference with mental tasks required by their job (OR 3.67, CI 2.16–6.24, p <0.01) and taking extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or a change in hours, duties or employment status (OR 5.52, CI 2.78–10.94, p<0.01) compared to those not exposed to chemotherapy (Table 6). Survivors exposed to radiation were significantly more likely to report interference of physical tasks required by their job (OR 3.11, CI 1.41–6.88, p<0.01) and taking extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or make a change in their hours, duties or employment status (OR 2.31, CR 1.02–5.22, p<0.05). Furthermore, among survivors who were working, those who underwent surgery were significantly more likely to report interference with mental tasks required by their job (OR 2.01, CI 1.03–3.92, p <0.05) compared to those who did not undergo surgery within the same gender, age (categorical), chemotherapy and radiation exposure. Analyses were performed for joint associations between treatment exposure to surgery and radiation and no statistically significant associations found. Finally, AYA survivors who were exposed to chemotherapy were significantly more likely to report that they or their families borrowed greater than $10,000 (OR 3.42, CI 1.50–7.83, p<0.01) compared to survivors not exposed to chemotherapy with the same gender, age (categorical), radiation and surgery exposure.

Table 6:

Association of cancer directed treatment factors and physical and mental impairment at work, and change in employment among young adults cancer survivors other than breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma or thyroid cancer working at any time from diagnosis to study participation.

| Chemotherapy † | Radiation ‡ | Surgery § | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| n Chemotherapy/ n no Chemotherapy (%) |

OR | 95% CI | n Radiation/ n no Radiation (%) |

OR | 95% CI | n Surgery/ n no Surgery (%) |

OR | 95% CI | |||||||||||||||||

| Interfered with physical tasks required by job | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 31 / 58 (34.8) | 1.00 | Ref | 14 / 75 (15.7) | 1.00 | Ref | 68 / 21 (76.4) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 68 / 66 (50.7) | 1.70 | (0.89–3.23) | 45 / 89 (33.6) | 3.11 | (1.41–6.88) | ** | 113 / 21 (84.3) | 2.28 | (1.09–4.76) | * | ||||||||||||||

| Interfered with mental tasks required by job | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 40 / 97 (29.2) | 1.00 | Ref | 28 / 109 (20.4) | 1.00 | Ref | 107 / 30 (78.1) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 95 / 59 (61.7) | 3.67 | (2.16–6.24) | ** | 47 / 107 (30.5) | 1.56 | (0.84–2.92) | 134 / 20 (87.0) | 2.06 | (1.05–4.02) | * | ||||||||||||||

| Extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or a change in your hours, duties or employment status | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 14 / 63 (18.2) | 1.00 | Ref | 10 / 67 (13.0) | 1.00 | Ref | 60 / 17 (77.9) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 122 / 94 (56.5) | 5.52 | (2.78–10.94) | ** | 66 / 150 (30.6) | 2.31 | (1.02–5.22) | * | 183 / 33 (84.7) | 1.70 | (0.85–3.40) | ||||||||||||||

| Extended paid time off from work | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 36 / 31 (53.7) | 1.00 | Ref | 20 / 47 (29.9) | 1.00 | Ref | 59 / 8 (88.1) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 83 / 58 (58.9) | 0.93 | (0.47–1.82) | 46 / 95 (32.6) | 1.16 | (0.54–2.47) | 118 / 23 (83.7) | 0.62 | (0.23–1.71) | ||||||||||||||||

| Unpaid time off from work | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 47 / 33 (58.8) | 1.00 | Ref | 28 / 52 (35.0) | 1.00 | Ref | 66 / 14 (82.5) | 1.00 | Ref | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 72 / 54 (57.1) | 1.19 | (0.63–2.28) | 38 / 88 (30.2) | 0.86 | (0.43–1.70) | 109 / 17 (86.5) | 1.47 | (0.62–3.51) | ||||||||||||||||

Adjusted for age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, radiation status, and surgery status.

Adjusted for age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, chemotherpy status, and surgery status.

Adjusted for age (categorical), gender, education (categorical), insurance, chemotherapy status, and radiation status.

p-value <0.05

p-value <0.01

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study of AYA cancer survivors, among the entire study population, radiation was associated with an increase odds of reporting physical impairments of work tasks and chemotherapy was associated with an increased likelihood of reporting both physical and mental impairment of work tasks as well as an increased likelihood of taking any time off work. In subgroup analyses by diagnosis, we found that chemotherapy was associated with an increased odds of mental impairment of work tasks in AYA breast and ‘other’ cancer survivors, an increased odds of taking paid time off from work in breast cancer survivors, an increased odds of taking any time off work in AYA ‘other’ cancer survivors, and an increased odds of AYA ‘other’ cancer survivors or their families borrowing greater than $10,000. Exposure to radiation therapy was associated with an increased odds of mental impairment of work tasks in AYA breast cancer survivors, an increased odds of taking an extended paid time off work in AYA thyroid cancer and an increased odds of physical impairment and taking any time off work in ‘other’ cancer survivors. Exposure to having had a surgical procedure was associated with an increased odds of physical and mental impairment of work tasks in ‘other’ cancer survivors which contained participants with sarcoma and central nervous system cancers. Finally among breast cancer survivors who were working, those who received chemotherapy were more likely to take extended time off work compared to those received both chemotherapy and radiation. This association may be explained by the fact that the authors were unable to determine participants who stopped working versus those who took extended paid time off. Participants who stopped working were not captured by the survey questions. This may have resulted in the chemotherapy only group have reported taking more time extended time off whereas those that received combined chemotherapy and radiation may have actually stopped working entirely, but this would not have been captured by the survey. Supporting this explanation, those who received combined chemotherapy and radiation were also more likely to have advanced disease.

Although there is a considerable amount of research specifically addressing cancer and work outcomes, most have focused on the likelihood and timeliness of work return after cancer 13,14. The Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience Study (AYA HOPE) evaluated the impact of cancer on work and education in cohort of 463 patients age 15 to 39 years recently diagnosed with cancer from participating Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registries. The authors found that although most AYA patients with cancer return to work after cancer, more than 50% continued to report some problems with work/studies on return 15. The authors also demonstrated that among full-time workers/students before diagnosis, those diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma were less likely than other cancer types to be working/in-school at follow-up 15. These results support the finding that leukemia and lymphoma participants who received radiation were more likely to take extended time off work due to their caner. Studies using the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study have evaluated return to work among adult survivors of childhood cancer and found that survivors have higher levels of unemployment because of health or being between jobs more often than siblings. In addition, cranial radiotherapy at doses ≥ 25 Gy was associated with higher odds of unemployment 12. Prior data in breast cancer patients has also indicated that the type of treatment is the principal determinant in the time taken to return to work 17. A study of Korean breast cancer survivors showed that fatigue and exhaustion were the most frequent difficulties encountered by survivors during occupational work 18. We build on these findings, specifically for young adults, by identifying treatment factors that impact physical and mental impairment of work tasks as well the need to take time off work. Our study fills a gap in the literature as it relates to AYA cancer survivors and the impact of cancer-directed therapies on employment and financial outcomes in AYA cancer survivors and the physical and mental impairment they may face.

YA cancer survivors are a heterogeneous group and therefore the treatments, and morbidities from their treatment, are also likely to be heterogeneous. It is possible that the associations we see in each of the different cancer categories are related to advanced disease requiring intensification of therapy. For example, in the group with a diagnosis other than breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma or thyroid cancer, the association of radiation and physical limitations at work may be due to radiation exposure related to treatment of brain tumors included in this group.

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. As this is a one-time, cross-sectional study, our results do not capture the trajectories of impairments in the cancer survivor population. We also lacked information regarding the participant’s insurance status as this may the impact financial impact on survivors. Further, there were limitations related to the lower study enrollment rate. Although this presents the possibility of selection bias and could impact generalizability, this response rate is similar to that observed in other studies of adolescent and young adults cancer survivors such as the AYA HOPE Study 19. Limited study resources prevented any follow-up tracing efforts on cases lacking a correct address of phone number. We acknowledge that there is potential for selection bias in this study as the survivors who are not completing the survey may be systematically different from those who have completed the survey with respect to the outcomes. It is also important to acknowledge that self-reported limitations, either physical or mental, are not equivalent to demonstrated performance measures and may impact the results of self-reported chemotherapy related cognitive impairment as compared to formal neurocognitive testing. For analyses of exposure to chemotherapy, there was not sufficient power or data to distinguish participants according to chemotherapy agent or regimen as it is possible that some chemotherapy regimens may have more long-term consequences than others. Finally, it is also possible that treatment exposures could be a proxy for disease severity and advanced disease may actually have a direct impact on mental and physical impairment at work. Patients with more advanced disease may have received more intensive therapy and it is possible that symptoms of the disease itself, rather than direct effects of the treatment, could partially explain observed associations.

In summary, our study is the first to our knowledge to describe associations of cancer-directed therapy on employment and financial implications in a multi-center, large cohort of AYA cancers survivors. This work is important in understand the challenges unique to AYA cancer survivors as it relates to their employment during and after their cancer therapy. The results from our study suggest that further longitudinal studies and interventions are needed to describe and support AYA cancer survivors in the work-force during and after cancer-directed therapy.

ACKNOWLEGEMENT:

This investigation was supported by the Livestrong Foundation, National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32CA009351 and grants from the National Cancer Institute, CA215134, 5P30 CA015704, CA 204378, and CA201179. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources:

Livestrong Foundation,NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32CA009351 National Cancer Institute, CA215134, 5P30 CA015704, CA204378, and CA201179.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescnts and Young Adults with Cancer. Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. August 2006.

- 2.Tai E, Pollack LA, Townsend J, Li J, Steele CB, Richardson LC. Differences in non-Hodgkin lymphoma survival between young adults and children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(3):218–224. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer A Young adult oncology: the patients and their survival challenges. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(4):242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pendley JS, Dahlquist LM, Dreyer Z. Body image and psychosocial adjustment in adolescent cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22(1):29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson RC, Nelson MB, Meeske K. Young adult survivors of childhood cancer: attending to emerging medical and psychosocial needs. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs Off J Assoc Pediatr Oncol Nurses. 1999;16(3):136–144. doi: 10.1177/104345429901600304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(6):1024–1031. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grinyer A The biographical impact of teenage and adolescent cancer. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(4):265–277. doi: 10.1177/1742395307085335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al. Employment Implications of Informal Cancer Caregiving. J Cancer Surviv Res Pract. 2017;11(1):48–57. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0560-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banegas MP, Dickerson JF, Kent EE, et al. Exploring barriers to the receipt of necessary medical care among cancer survivors under age 65 years. J Cancer Surviv Res Pract. 2018;12(1):28–37. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0640-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banegas MP, Guy GP, de Moor JS, et al. For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2016;35(1):54–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.RStudio Team. R Studio: Integrated Development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc.; 2016. http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12):1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30677-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Boer AGEM Taskila TK, Tamminga SJ, Feuerstein M, Frings-Dresen MHW, Verbeek JH Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD007569. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007569.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roelen CAM, Koopmans PC, de Graaf JH, Balak F, Groothoff JW. Sickness absence and return to work rates in women with breast cancer. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82(4):543–546. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0359-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Lynch CF, et al. Impact of cancer on work and education among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2393–2400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Med Care. 2010;48(11):1015–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balak F, Roelen CAM, Koopmans PC, Ten Berge EE, Groothoff JW. Return to work after early-stage breast cancer: a cohort study into the effects of treatment and cancer-related symptoms. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(3):267–272. doi: 10.1007/s10926-008-9146-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn E, Cho J, Shin DW, et al. Impact of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on work-related life and factors affecting them. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116(3):609–616. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0209-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan THM, et al. Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE Study. J Cancer Surviv Res Pract. 2011;5(3):305–314. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0173-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]