Neprilysin (NEP) is a cell membrane bound metalloendopeptidase which when released from the cell surface results in the formation of a circulating peptide that maintains its catalytic activity (1, 2). NEP helps to mediate the anti-fibrotic, anti-proliferative, myocardial relaxation, vasodilator and diuretic properties of natriuretic peptides (NPs) by participating in NP homeostasis. NPs are degraded and cleared by a variety of processes in which NEP participates and by the NP clearance receptor. NEP has been reported to be responsible for removal of at least 50% of circulating NPs (3). Increased circulating NEP levels was found to be significantly associated with the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.17; p=0.001) and cardiovascular death (HR: 1.19; p=0.002) in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (4). This association remains significant after adjustment for age, sex, LVEF, New York Heart Association functional class, diabetes mellitus, renal function, HF therapy, NT-proBNP levels and other known risk factors. Therefore a therapeutic strategy of inhibiting NEP presumably to augment endogenous NPs for their beneficial effects served as a basis for the PARADIGM-HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) trial. Sacubitril/valsartan, a crystalline complex of a neprilysin inhibitor (sacubitril) and an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB, valsartan), was recently approved to treat NYHA Class 2–4 patients with HFrEF after the PARADIGM-HF trial was stopped early due to an overwhelming benefit of the drug in reducing all-cause mortality (HR 0.84; p<0.001), CV mortality (HR 0.80; p<0.001), hospitalization for HF (HR 0.79; p<0.001) and in addition a reduction in the symptoms and physical limitations of HF by 21% (p=0.001) (5). The beneficial effects of sacubitril/valsartan, in addition to the effect of the ARB component, were assumed to be due to the impact of NEP inhibition on NPs clearance. However, the concept that augmentation of atrial or B-type NP or both contributed to these beneficial effects was not proven. In addition, NEP serves as a metabolizing enzyme for a large number of other substances such as substance P, bradykinin and adrenomedullin which may also be relevant in HFrEF (5). To further elucidate the mechanism of the beneficial effects of sacubitril/valsartan especially given the wide spread effects of NEP, Nougué et al converted 73 chronic HFrEF outpatients from ACE inhibitor or ARB to sacubitril/valsartan (6). ANP, BNP, NT-proBNP, proBNP glycosylation and NEP concentration and activity were measured at baseline before and 30 and 90 days after initiation of therapy. Other substances that serve as substrates of NEP such as GLP-1, adrenomedullin and substance P were also measured. In addition markers of heart failure severity including high-sensitive cardiac troponin I (hsTnI), soluble ST2 (sST2) and CD146 (sCD146) levels were assayed. NYHA functional class and echocardiographic parameters were analyzed at periodic intervals including before and 180 days after treatment. This single arm, open label study demonstrated an improvement in NYHA functional class within 30 days of sacubitril/valsartan treatment and significant improvement in echocardiographic parameters such as LVEF and Doppler indices of cardiac output and pulmonary arterial pressures at 6 months. There was also a significant reduction in surrogate markers of HF severity and prognosis such as hsTnI, NT-proBNP and sST2 starting as early as 30 days after initiation of sacubitril/valsartan.

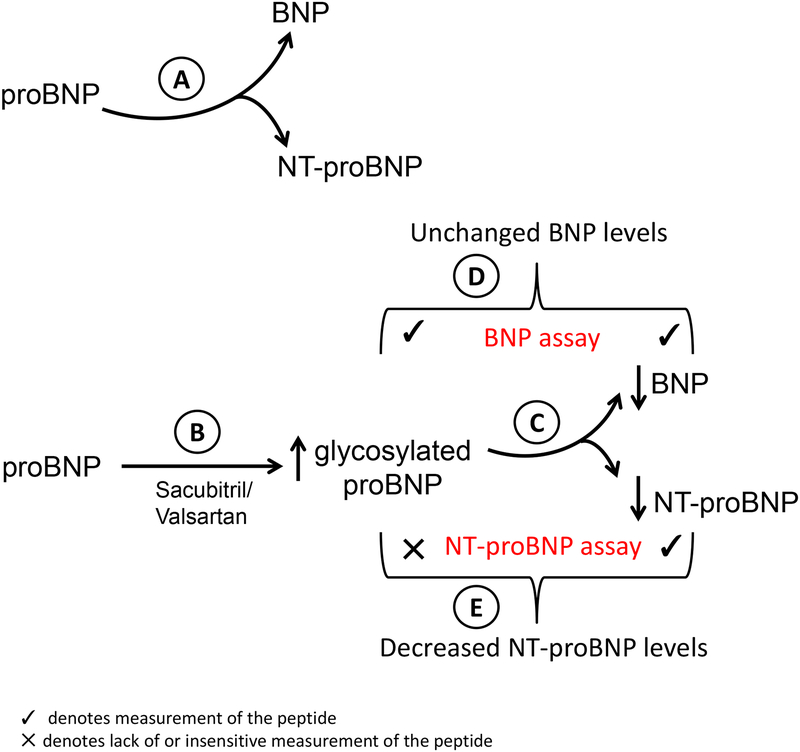

To provide mechanistic insights into the beneficial effects of sacubitril/valsartan, NEP levels and activity and NP levels were measured before and after treatment. Expectedly, a dose-dependent decrease in sNEP activity was observed with most of the decrease in activity being observed at the 49/51 mg sacubitril/valsartan dose. This finding is concordant with the observation in this and other studies that the decrement in NT proBNP, a marker of clinical efficacy with sacubitril/valsartan treatment, is most marked with the 49/51 mg dose with little incremental biochemical benefit on this parameter seen with a higher dose. The authors in a prior study have demonstrated that high BNP levels inhibits sNEP activity at baseline which led to questioning whether the mechanism of NEP inhibition in this subgroup of patients was mediated by its effects on NPs (7). However, most patients in the current study appeared to favorably respond to sacubitril/valsartan therapy despite high BNP levels. Pardoxically, there was no change in sNEP concentrations observed with sacubitril/valsartan therapy. This may reflect the problems of sNEP measurements. The correlation of the various assays measuring sNEP is poor and such assays require rigorous quality control. In addition the clinical determinants of sNEP levels in large populations such as smoking are only recently known (8); therefore adjustment for such variables should be considered when interpreting sNEP levels. In response to sacubitril/valsartan treatment, ANP levels increased predictably as it is a substrate for NEP, but the concentration of the other substrate BNP did not change, glycosylated proBNP levels increased and as discussed above NT-proBNP levels decreased. At baseline, it has been proposed that non glycosylated proBNP is cleaved into BNP and NT-proBNP (Figure-A). The present study demonstrates that sacubitril/valsartan therapy results in an increase in glycosylated proBNP (Figure-B) which will inhibit such cleavage. Glycosylated proBNP, resists cleavage into BNP and NTproBNP that theoretically could result in lower BNP and NT-proBNP concentrations (Figure-C). However, the antibody used in BNP assays cross-react with proBNP, therefore in effect the assay measures the sum of BNP and proBNP, which explains why an overall change in measured BNP levels may not be observed (Figure-D). (9–11). The antibody used in measuring NT-proBNP cross-reacts with non-glycosylated proBNP but not glycosylated proBNP and therefore the assay for NT-proBNP measures an apparent drop in NT-proBNP levels with sacubitril/valsartan therapy that occurs due in part to an increase in glycosylated and thus unmeasured proBNP (Figure-E). This hypothesis would then question whether the decrease in NT-proBNP observed with sacubitril/valsartan is a direct biochemical effect or is reflective of a true beneficial hemodynamic effect. The echocardiographic findings of improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction and filling pressures in this study that correlated with reductions in NT-proBNP is suggestive that the drop in NT-proBNP may be in part a consequence of a true beneficial hemodynamic effect in addition to the biochemical effect described above. A significant reduction in NT-proBNP with sacubitril/valsartan therapy has been as with other drug therapy associated with a lower rate of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization in the PARADIGM-HF study supporting the beneficial hemodynamic effect hypothesis (12). More recently in the PIONEER-HF trial, inpatient introduction of sacubitril/valsartan for patients with HFrEF resulted in a significant reduction in NT-proBNP compared to enalapril with the implication that this observation was a surrogate marker of efficacy whether it is a primary mechanism or not. Interestingly, a 29% decrease in BNP was observed with sacubitril/valsartan therapy which could be due to differences in the BNP assay used which respond very differently to glycosylation (10). The trial itself was not powered for reduction in clinical events and such a reduction was not observed when analyzed as an exploratory endpoint (13). An alternative explanation for the lack of change in BNP levels is the experimental observation that BNP itself is relatively resistant to hydrolysis and cleavage by NEP as compared to ANP and therefore NEP inhibition may not result in significant changes in BNP concentration (14). Finally, BNP and proBNP levels are influenced by furin, a membrane bound protease that cleaves proBNP, the activity of which may be down regulated by sacubitril/valsartan (15).

Figure 1.

Change in BNP and NT-proBNP levels in response to sacubitril/valsartan based on specificity of individual assays

Irrespective, the 4-fold increase in ANP but lack of increase in BNP levels led the authors to conclude that ANP not BNP is the mediator of sacubitril/valsartan effect. In a much larger cohort of the PARADIGM-HF trial (27% of the randomized 8399 participants had biomarkers measured), although BNP levels were measured at 4 weeks and 8 months with sacubitril/valsartan therapy these were not compared to baseline levels hence change in BNP levels in the sacubitril/valsartan arm is unclear. ANP levels were not measured in this study (18). In a study evaluating the effect of sacubitril/valsartan in hypertension, a 13 to 18% increase in ANP was observed in contrast to a 9–11% decrease with valsartan therapy compared to baseline corresponding to a greater reduction in blood pressures with sacubitril/valsartan (19). BNP levels were not measured in this study. In a much smaller study of 30 participants with HFrEF, urinary ANP levels significantly increased with a corresponding increase in cGMP and decrease in NT-proBNP with sacubitril/valsartan treatment however BNP was not measured (20). The data including the study by Nougué et al support the hypothesis that perhaps the beneficial mechanism of action of sacubitril/valsartan maybe mediated by ANP however an increase in other substrates of NEP such as adrenomedullin, a substance that modulates fibroblast proliferation, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and has a positive inotrope effect (21), may also play a pivotal role as demonstrated in this study (Supplementary Figure 3 (6). More conclusive evidence may emerge after the results of PROVE-HF are available. PROVE-HF is an open label, single arm study evaluating biomarker changes that will be correlated with echocardiographic remodeling parameters and patient-reported outcomes assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in approximately 830 patients with HFrEF (22). The PROVE-HF study will also measure adrenomedullin, which along with bradykinin, another NEP substrate, could have a beneficial effect on cardiac remodeling. Other substances that are substrates for NEP such as substance P that in this study (Supplementary Figure 3 (6) was expectedly increased with sacubitril/valsartan and endothelin could theoretically have deleterious long-term effects in heart failure but have not translated into adverse clinical events in clinical trials. Therefore, these findings, question the value of change in biomarkers with drug administration in determining the mechanisms for beneficial clinical outcomes. This is similar to the lack of change in angiotensin 2 levels with ACE-I (23) despite the beneficial effects of ACE-I in hypertension and HF. The study by Nougué et al support this concept as the biomarkers other than NT-proBNP measured at baseline or during follow-up did not correlate with an improvement in clinical parameters such as NYHA Class or LVEF, however the study may have been underpowered to detect such changes. These observations reflect the complexity of drug action on feedback loops of the various biomarkers, and its effect on systems biology.

An important consideration in interpreting the measurement of the various components of the natriuretic peptide system are the assays used to evaluate the system and the variability of the assays used in different studies. For example, there was no correlation observed in serum NEP levels when measured by 4 different commercial assays (16). The authors measured sNEP levels by using the USCN assay that was found to correlate poorly (R2=0.3) with the Aviscera assay that was used to determine prognostic significance in a chronic HF population. Whether the variability in NEP assays account for the discrepancy observed in this study between NEP enzymatic activity that was reduced but NEP levels that were unchanged is unclear as typically a linear correlation is expected and observed between enzymatic activity and concentration (17). It is well known and acknowledged in this study that BNP assays measure both many BNP and proBNP fragments. The cross-reactivity with non-glycosylated proBNP and lack of cross-reactivity with glycosylated proBNP that increases with sacubitril/valsartan therapy for assays measuring NT-proBNP (10) also validates the observations and conclusions reached in this study. The biologically active form of ANP was measured using tandem mass spectrometry a reliable assay for a peptide that has a short half-life so it is probably not influenced markedly.

In conclusion, sacubitril/valsartan therapy in patients with HFrEF resulted in improvement in clinical symptoms, echocardiographic parameters and prognostic biomarkers. The beneficial effects of treatment are likely mediated by ANP and other substances that are substrates for NEP but they are unlikely to be mediated by BNP.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Allan Jaffe acknowledges that he consults for most of the major diagnostic companies and Novartis which makes the drug studied in this report.

Dr. Naveen Pereira is supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R21AG53512.

Dr. Viral Desai has no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Naveen L. Pereira, Professor of Medicine and Associate Professor of Pharmacology, Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; Department of Molecular Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics

Viral K. Desai, Visiting Research Fellow, Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

Allan S. Jaffe, Professor of Medicine and Professor of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Consultant in Cardiology and Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Chair, Division of Core Clinical Laboratory Service, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology

References

- 1.Knecht M, Pagel I, Langenickel T, Philipp S, Scheuermann-Freestone M, Willnow T, et al. Increased expression of renal neutral endopeptidase in severe heart failure. Life sciences. 2002;71(23):2701–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fielitz J, Dendorfer A, Pregla R, Ehler E, Zurbrugg HR, Bartunek J, et al. Neutral endopeptidase is activated in cardiomyocytes in human aortic valve stenosis and heart failure. Circulation. 2002;105(3):286–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charles CJ, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Richards AM, Yandle TG, Protter A, et al. Clearance receptors and endopeptidase 24.11: equal role in natriuretic peptide metabolism in conscious sheep. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(2 Pt 2):R373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helske S, Laine M, Kupari M, Lommi J, Turto H, Nurmi L, et al. Increased expression of profibrotic neutral endopeptidase and bradykinin type 1 receptors in stenotic aortic valves. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(15):1894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nougue H, Pezel T, Picard F, Sadoune M, Arrigo M, Beauvais F, et al. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on neprilysin targets and the metabolism of natriuretic peptides in chronic heart failure: a mechanistic clinical study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vodovar N, Seronde MF, Laribi S, Gayat E, Lassus J, Januzzi JL Jr., et al. Elevated Plasma B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Concentrations Directly Inhibit Circulating Neprilysin Activity in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(8):629–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy YN, Iyer SR, Scott CG, Rodeheffer RJ, Bailey K, Redfield MM, et al. Abstract 16084: Serum Neprilysin and Its Relationship to Cardiovascular Disease in the General Population. Circulation. 2018;138(Suppl_1):A16084–A. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seferian KR, Tamm NN, Semenov AG, Tolstaya AA, Koshkina EV, Krasnoselsky MI, et al. Immunodetection of Glycosylated NT-proBNP Circulating in Human Blood. Clin Chem. 2008;54(5):866–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasile VC, Jaffe AS. Natriuretic Peptides and Analytical Barriers. Clin Chem. 2017;63(1):50–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenov AG, Katrukha AG. Different Susceptibility of B-Type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) and BNP Precursor (proBNP) to Cleavage by Neprilysin: The N-Terminal Part Does Matter. Clin Chem. 2016;62(4):617–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zile MR, Claggett BL, Prescott MF, McMurray JJ, Packer M, Rouleau JL, et al. Prognostic Implications of Changes in N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(22):2425–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, Duffy CI, Ambrosy AP, McCague K, et al. Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. N Engl J Med.0(0):null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenny AJ, Bourne A, Ingram J. Hydrolysis of human and pig brain natriuretic peptides, urodilatin, C-type natriuretic peptide and some C-receptor ligands by endopeptidase-24.11. The Biochemical journal. 1993;291(Pt 1):83–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vodovar N, Seronde MF, Laribi S, Gayat E, Lassus J, Boukef R, et al. Post-translational modifications enhance NT-proBNP and BNP production in acute decompensated heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(48):3434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayes-Genis A, Barallat J, Richards AM. A Test in Context: Neprilysin: Function, Inhibition, and Biomarker. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(6):639–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira NL, Aksoy P, Moon I, Peng Y, Redfield MM, Burnett JC Jr., et al. Natriuretic peptide pharmacogenetics: membrane metallo-endopeptidase (MME): common gene sequence variation, functional characterization and degradation. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2010;49(5):864–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2015;131(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruilope LM, Dukat A, Bohm M, Lacourciere Y, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP. Blood-pressure reduction with LCZ696, a novel dual-acting inhibitor of the angiotensin II receptor and neprilysin: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active comparator study. Lancet. 2010;375(9722):1255–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobalava Z, Kotovskaya Y, Averkov O, Pavlikova E, Moiseev V, Albrecht D, et al. Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Sacubitril/Valsartan (LCZ696) in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;34(4):191–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishikimi T, Yoshihara F, Mori Y, Kangawa K, Matsuoka H. Cardioprotective effect of adrenomedullin in heart failure. Hypertension research: official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2003;26 Suppl:S121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Januzzi JL, Butler J, Fombu E, Maisel A, McCague K, Piña IL, et al. Rationale and methods of the Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement, and Ventricular Remodeling During Sacubitril/Valsartan Therapy for Heart Failure (PROVE-HF). American Heart Journal. 2018;199:130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamura M, Imanashi M, Matsushima Y, Ito K, Hiramori K. Circulating angiotensin II levels under repeated administration of lisinopril in normal subjects. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology. 1992;19(8):547–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]