Abstract

Purpose:

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often co-occurs with panic disorder (PD), with some etiological models positing a causal role of panic reactivity in PTSD onset; however, data addressing the temporal ordering of these conditions are lacking. The aim of this study was to examine the bi-directional associations between PD and PTSD in a nationally representative, epidemiologic sample of trauma-exposed adults.

Methods:

Participants were community-dwelling adults (62.6% women; Mage=48.9, SD=16.3) with lifetime DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A trauma exposure drawn from the 2001/2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) and re-interviewed in 2004/5 (N=12,467). Cox discrete-time proportional hazards models with time-varying covariates were used to investigate the bi-directional associations between lifetime PD and PTSD, accounting for demographic characteristics, trauma load, and lifetime history of major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder.

Results:

PD was significantly associated with subsequent onset of PTSD (HR=1.210, 95%CI=1.207-1.214, p<.001), and PTSD was significantly associated with onset of PD (HR=1.601,95%CI=1.597-1.604, p<.001). The association between PTSD and subsequent PD was stronger in magnitude than that between PD and subsequent PTSD (Z=−275.21, p<.01). Men evidenced stronger associations between PD and PTSD compared to women.

Conclusions:

Results were consistent with a bidirectional pathway of risk, whereby PD significantly increased risk for the development of PTSD, and PTSD significantly increased risk for PD. Given the association between PTSD and subsequent PD, particularly among men, clinicians may consider supplementing PTSD treatment with panic-specific interventions, such as interoceptive exposure, to prevent or treat this disabling comorbidity.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, epidemiology, panic attack, trauma

Introduction

Exposure to a potentially traumatic event (PTE; e.g., physical or sexual assault, transportation accident, combat exposure) is a necessary condition for the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [1]. PTE exposure is quite common, with epidemiological studies estimating that up to 89% of the population will experience one or more PTEs over the course of their lifetime (Kilpatrick et al., 2013); however, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 7-8% (Kilpatrick et al., 2013; Kessler et al., 1995), with the conditional probability of PTSD given PTE exposure ranging from 9-11% when not specifying a particular type of PTE exposure (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Further, PTE exposure also is associated with increased risk for a wide array of psychiatric conditions, including panic disorder, major depression, specific phobias, and substance use disorders [2-4], with many of these conditions often co-occurring with PTSD [5; 6]. Significant focus in the trauma literature has been devoted to comorbidity with panic- spectrum psychopathology. Multiple lines of evidence support a relationship between PTE exposure and/or PTSD with panic psychopathology. PTE exposure is related to increased incidence of panic attacks [7; 8], and approximately 69% of individuals seeking treatment for PTSD meet current criteria for panic attacks [9]. Similarly, individuals with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (PD/PDA) often report histories of PTEs [10], and both clinical and epidemiologic samples indicate that PTSD and PD/PDA are highly comorbid [5; 11; 12].

In spite of high rates of co-occurrence between PTSD and panic-spectrum psychopathology, the nature of this co-occurrence is not well understood. Theoretical models suggest that panic attacks and panic reactivity (i.e., a tendency to endorse panic symptoms in response to physiological arousal) may play a causal role in PTSD etiology. Specifically, it has been hypothesized that peri-traumatic panic attacks (i.e., panic attacks experienced during a PTE) may facilitate trauma-relevant fear conditioning, subsequently increasing risk for PTSD [8; 13], with empirical evidence supporting a relationship between peri-traumatic panic attacks and increased likelihood of developing PTSD [14; 15]. However, the role of more severe panic psychopathology in PTSD etiology has received less attention in the literature. In addition, sex differences in PD/PDA and PTSD comorbidity are unclear. Investigating potential differences in comorbidity on the basis of sex is important, given that women are more likely than men to meet criteria for PD/PDA and PTSD, in spite of men and women experiencing comparable rates of PTEs [16; 17].

There is evidence for a common liability model of co-occurring PD/PDA and PTSD, as PTSD and PD/PDA share common genetic and unique environmental risk [18–21], indicating that shared liability may account for high rates of co-morbidity. Indeed, similarities exist with regard to underlying physiology of PTSD and PD/PDA. For example, PTSD and PD/PDA, but not other anxiety disorders, are associated with autonomic arousability [22], such that individuals with PTSD and PD/PDA have similar patterns of self-reported and physiological anxiety in response to laboratory-induced arousal [23]. Similarly, comparison of cortisol stress response in clinical and non-clinical samples indicates a cortisol hypo-responsiveness common to individuals with PTSD and PD [24]. Putative individual difference characteristics, such as anxiety sensitivity [25; 26] and distress tolerance [27; 28], also have been associated with both disorders. Finally, peripheral evidence from treatment-outcome research is consistent with a common liability model of PD/PDA and PTSD. Specifically, in a sample of patients with comorbid PD-PTSD, treatment of PTSD with cognitive behavioral methods demonstrated concurrent reduction in panic symptoms, even in the absence of panic-focused treatment [29].

Epidemiologic studies of PD/PDA and PTSD may be useful in evaluating the nature of the etiologic relationship between PD/PDA and PTSD. For example, evaluating the temporal associations between PD/PDA and PTSD and the strength of these associations would point to whether this relationship is primarily uni- or bi-directional. If the strength of the association between PTSD and subsequent PD/PDA is comparable to that of PD/PDA and subsequent PTSD, this bi-directional relationship would be consistent with the etiologic hypothesis that common underlying liability (i.e., genetic or environmental factors) shared by both conditions may be responsible for their co-occurrence. However, if the data are more consistent with a uni-directional relationship, for example that the risk of PTSD subsequent to PD/PDA is substantially greater than the risk of PD/PDA subsequent to PTSD, this would support an etiologic model of a direct, causal relationship, potentially related to the influence of panic psychopathology on fear conditioning. To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined the bidirectional association between PD/PDA and PTSD within a population-based sample.

The aim of this study was to examine the bi-directional association between PD/PDA and PTSD in a sub-set of trauma-exposed adults participating in a national epidemiologic research study. Specifically, we examined both the risk of PTSD associated with prior PD/PDA, and the risk of PD/PDA associated with prior PTSD. We hypothesized that the association between PD/PDA and subsequent PTSD would be stronger in magnitude than the reverse association, based on theory and existing literature highlighting panic processes as risk factors for PTSD. Given observed sex differences in the prevalence of PD/PDA and PTSD, we also examined whether associations between PD/PDA and PTSD differed by sex.

Method

Participants

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is a longitudinal, nationally representative population-based survey of community-dwelling US adults. Details of the study design have been described previously [30]. Briefly, baseline interviews were conducted in 2001/2 (n=43,093, response rate: 81.0%), with a follow-up wave in 2004/5 (n=34,653, response rate: 86.7%). Interviews were conducted in person by trained, lay interviewers. The current investigation is limited to participants who completed both waves of interviews (N=34,653), with the primary analyses limited to the subset of the sample that met lifetime DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A trauma exposure (N=12,467). This was necessary because only individuals with a Criterion A trauma are eligible for a diagnosis of PTSD. The US Census Bureau and the US Office of Management and Budget reviewed and approved the research protocol and informed consent procedures. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Measures

Psychiatric disorders were assessed using the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule, DSM-IV version [31]. The AUDADIS-IV has good test-retest reliability and moderate agreement against structured clinical interviews [32]. The AUDADIS-IV also was used to assess substance use and other psychiatric disorders.

PTSD and trauma exposure were only assessed at Wave 2. Within the PTSD module, respondents were queried on whether they had experienced a range of PTEs (e.g., motor vehicle accident, sexual assault, sudden death of a loved one, etc.). DSM-IV Criterion A for PTSD was assessed for participants’ self-identified “worst” traumatic event, and all other PTSD symptoms were assessed in reference to this Criterion A event. Age of onset of PTSD, based on individuals’ “worst” event,” was assessed for those who met diagnostic criteria for lifetime PTSD. For individuals with lifetime PTSD who were missing age of onset data (1.5%), the data were imputed based on the median age of onset of participants in the same age decade. A sum score of the number of PTE categories endorsed served as a covariate for the present analyses to ensure that observed associations between PD/PDA and PTSD were not better accounted for by differences in trauma load.

PD/PDA was initially assessed using three probe questions including: (1) “Have you ever had a panic attack, when all of a sudden you felt frightened, overwhelmed or nervous, almost as if you were in great danger, but really weren’t?” (2) “Were you ever very surprised by a panic attack that happened totally out-of-the-blue, for no real reason, or in a situation where you didn’t expect to be frightened?” (3) “Did you ever think you were having a heart attack, but the doctor said it was just nerves or you were having a panic attack?” Respondents who endorsed at least one of these problems were queried further about the presence of DSM-IV panic attack symptoms (e.g., racing heart, shortness of breath), frequency of attacks, and interference in functioning. Agoraphobia was assessed using DSM-IV criteria by asking respondents about their avoidance of a number of situations (e.g., crowded places, closed spaces, flying, traveling on buses), whether panic attacks were associated with such specific situations, and whether the person experienced interference in their daily functioning because of their discomfort with the endorsed situations.

PD/PDA was assessed at both Wave 1 and Wave 2; however, age of onset was not obtained for new cases with onset occurring between Waves 1 and 2. For those cases that onset after Wave 1, age of onset for PD/PDA was imputed using date of birth and date of interview as: (1) mean age in the year prior to interview if onset occurred in the past year, or (2) mean age during that approximate two year window between Wave 1 and the year prior to Wave 2 if onset occurred after Wave 1 but prior to the year of the Wave 2 interview. For individuals with lifetime PD/PDA who were missing age of onset data (1.7%), the data were imputed based on the median age of onset of participants in the same age decade.

Lifetime major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder also were assessed using the AUDADIS-IV. For the purposes of this study, lifetime history of each disorder was considered positive if a participant met criteria at either the Wave 1 or Wave 2 assessment. Each disorder was coded as 0 (“absent”) or 1 (“present”).

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine the distribution of PD/PDA and PTSD age of onset, as well as the distribution of the difference in age of onset among individuals with histories of PD/PDA and PTSD (i.e., age of onset of PD/PDA – age of onset of PTSD). Analyses were conducted in the total trauma-exposed sample, as well as stratified by sex.

Two Cox proportional hazards (PH) models were conducted: (1) PD/PDA predicting PTSD onset; and (2) PTSD predicting PD/PDA onset. The predictor disorder represented a time-dependent covariate changing from 0 to 1 at the age of onset, with failure time for cases being the age of onset of the criterion disorder or censoring time (for non-cases) being the last observed age (i.e., Wave 2 age). In cases where individuals met criteria for both disorders, but the outcome disorder preceded the predictor disorder, the time-dependent covariate remained at 0 (i.e., the cases were retained in the analyses but did not contribute to the estimate of the relative risk). The estimates of the hazard ratio (HR), an approximation of the relative risk, accounted for the influence of incomplete information from right-censored observations (e.g., individuals who were at-risk of developing PD/PDA [or PTSD] but did not prior to the end of the observation period). All models were adjusted for demographic characteristics relevant to the outcomes of interest (i.e., age [in years], sex [reference group=male], race/ethnicity [reference group=white], and education level [reference group=“less than high school”]), number of PTE categories endorsed, and lifetime diagnoses (0, 1) of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Models also were run separately for men and women to evaluate potential sex differences in the associations between PD/PDA and PTSD. The determination of significant sex differences in the relationships between PD/PDA-PTSD was made by examining the difference between log relative risks, which produces a z-score and associated p-value of the difference between the size of the hazard ratios for men and women.

Sampling weights, described in detail elsewhere (Grant & Dawson, 2006), were applied to the Cox PH models. Statistical significance was defined as p<.05. All analyses were conducted in R 3.0 [33], with the Cox PH models being conducted using the coxph function in the survival package [34].

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Men had a younger age of first PTE compared to women and endorsed having experienced a greater number of PTE types compared to women. Women were more likely than men to meet criteria for lifetime PD/PDA and PTSD. Among individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of PD/PDA (n=1,286), the mean age of onset was 34.7 years (SD=14.6). Men and women did not significantly differ in their average age of onset of PD/PDA (M=33.8 and M=35.1, respectively; t(570)=−1.36, p=0.175). Among individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD (n=2,463), the mean age of onset was 29.2 years (SD=16.5). Men and women did not significantly differ in their age of onset of PTSD (M= 28.2 and M=29.5, respectively; t(1339)=−1.81, p=0.071). Among individuals who met lifetime criteria for both PD/PDA and PTSD (n=804), 27.4% reported initial onset of PD/PDA, 67.2% reported initial onset of PTSD, and 5.5% reported onset within the same year. Among men who met lifetime criteria for both disorders (n=175), 33.7% reported initial PD/PDA onset, 59.4% initial PTSD onset, and 6.9% same-year onset; for women (n=629), 25.6% reported initial PD/PDA onset, 69.3% initial PTSD onset, and 5.1% same year onset.

Table 1.

National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Wave 2 (2004-2005) Trauma-Exposed Participants

| Total Trauma-Exposed Sample (N=12,467) | Trauma-Exposed Men (n=4,666) | Trauma-Exposed Women (n=7,801) | Test of Sex Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% women) | 62.6% | -- | -- | -- |

| Race/Ethnicity (%)a | ||||

| White | 60.6% | 62.2% | 59.6% | |

| African American | 18.6% | 15.9% | 20.2% | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.9% | 2.0% | 1.9% | |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific | 2.4% | 2.6% | 2.3% | |

| Islander | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 16.5% | 17.3% | 16.0% | |

| Mean Age (SD), in years | 49.3 (16.3) | 49.2 (16.0) | 49.4 (16.6) | t = −0.71, p = .475 |

| Highest Level of Education Completed (%) | ||||

| Less than high school degree | 14.0% | 13.9% | 14.1% | |

| High school or GED | 28.4% | 26.9% | 29.3% | |

| Some college/2-year degree | 32.2% | 31.3% | 32.8% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13.1% | 14.9% | 12.0% | |

| Some graduate school | 12.4% | 13.2% | 11.9% | |

| “Worst” Traumatic Event Endorsed | ||||

| Serious illness/injury of a loved one | 27.7% | 25.3% | 29.2% | χ2 = 22.26, p < .001 |

| Unexpected death of loved one | 22.7% | 20.7% | 23.9% | χ2 = 17.58, p < .001 |

| Indirect/direct experience of 9/11 or other terrorist link | 12.1% | 11.9% | 12.2% | χ2 = 0.21, p = .644 |

| “Other” traumatic event | 7.5% | 6.5% | 8.1% | χ2 = 12.00, p = .001 |

| Witnessing death/serious injury | 4.0% | 5.6% | 3.1% | χ2 = 50.61, p < .001 |

| Life-threatening illness | 3.7% | 3.6% | 3.8% | χ2 = 0.58, p = .448 |

| Exposure to combat/war zone | 3.4% | 8.3% | 0.5% | χ2 = 545.17, p < .001 |

| Serious accident | 3.3% | 5.4% | 2.1% | χ2 = 99.38, p < .001 |

| Physical assault | 2.7% | 1.1% | 3.6% | χ2 = 73.90, p < .001 |

| Sexual assault | 2.6% | 0.3% | 4.0% | χ2 = 155.68, p < .001 |

| Witnessing violence as child | 2.3% | 1.9% | 2.6% | χ2 = 6.36, p = .012 |

| Threatened with a weapon | 2.3% | 3.8% | 1.4% | χ2 = 71.68, p < .001 |

| Natural disaster | 2.0% | 2.5% | 1.7% | χ2 = 9.92, p = .002 |

| Physical assault/neglect as a child | 0.9% | 1.0% | 0.9% | χ2 = 0.92, p = .337 |

| Kidnapped/stalked | 0.9% | 0.5% | 1.1% | χ2 = 13.11, p < .001 |

| Number of potentially traumatic event categories endorsed | 4.38 (2.49) | 4.67 (2.56) | 4.20 (2.43) | t = 10.13, p < .001 |

| Mean age of first PTE (SD), in years | 18.53 (14.71) | 16.91 (12.61) | 19.52 (15.77) | t = 9.47, p < .001 |

| Lifetime PD/PDA | 10.3% | 7.0% | 12.3% | χ2 = 87.02, p < .001 |

| Lifetime PTSD | 19.8% | 14.4% | 22.9% | χ2 = 132.69, p < .001 |

| Lifetime major depression | 29.7% | 21.7% | 34.5% | |

| Lifetime generalized anxiety disorder | 11.4% | 7.8% | 13.6% | |

| Lifetime social anxiety disorder | 9.3% | 8.2% | 10.0% |

Cox Proportional Hazard Models

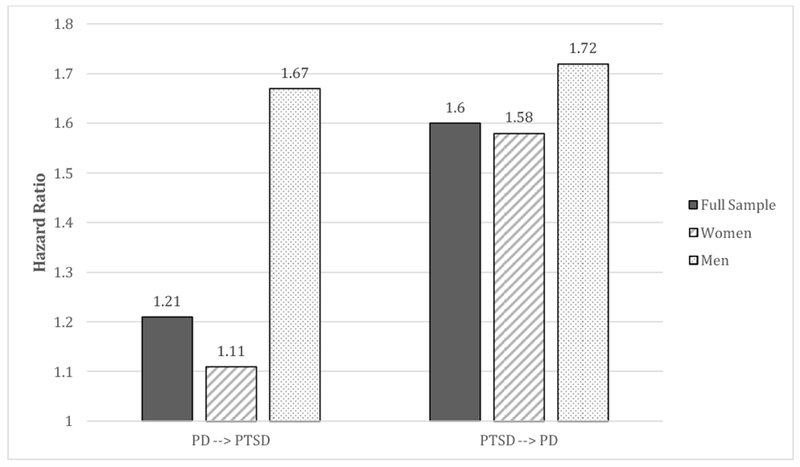

See Table 2 for output from the Cox proportional hazard models and Figure 1 for a graphical representation of hazard ratios for PD/PDA and PTSD predicting one another. A diagnosis of PD/PDA was associated with a 21% greater chance of developing PTSD, above and beyond the effect of the covariates. The association between PD/PDA and subsequent PTSD was stronger for men compared to women (test of gender comparison: Z=107.02, p<.01). Specifically, men with compared to without PD/PDA evidenced a 67% increased chance of developing PTSD, whereas women with compared to without PD/PDA only evidenced an 11% increased chance of developing PTSD.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard model output: Patterns of association between panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia; PD/PDA) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in an epidemiological sample

| Factors predicting PTSD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Trauma-Exposed Sample (N=12,467) | Trauma-Exposed Men (n=4,666) | Trauma-Exposed Women (n=7,801) | |

| PD/PDAa | 1.210* (1.207-1.214) | 1.670* (1.662-1.678) | 1.112* (1.108-1.115) |

| Wave 2 age | 0.976* (0.976-0.976) | 0.977* (0.976-0.977) | 0.975* (0.975-0.976) |

| Sex (0=male, 1=female) | 1.628* (1.625-1.630) | -- | -- |

| Race/ethnicity (0=white, 1=nonwhite) | 1.143* (1.142-1.145) | 1.049* (1.047-1.052) | 1.188* (1.186-1.190) |

| Education (1: high school/GED)b | 0.797* (0.796-0.799) | 1.019* (1.016-1.023) | 0.713* (0.711-0.714) |

| Education (2: some college) | 0.743* (0.741-0.744) | 0.786* (0.783-0.788) | 0.704* (0.702-0.706) |

| Education (3: Bachelor’s degree) | 0.710* (0.709-0.712) | 0.692* (0.689-0.694) | 0.721* (0.719-0.722) |

| Education (4: some graduate school) | 0.631* (0.629-0.632) | 0.547* (0.544-0.549) | 0.672* (0.670-0.673) |

| Number of potentially traumatic event categories endorsed | 1.161* (1.161-1.161) | 1.148* (1.147-1.149) | 1.172* (1.171-1.172) |

| Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | 2.102* (2.099-2.105) | 2.008* (2.003-2.013) | 2.079* (2.076-2.082) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | 1.579* (1.576-1.581) | 2.006* (2.000-2.012) | 1.502* (1.499-1.505) |

| Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) | 1.324* (1.321-1.326) | 1.367* (1.363-1.372) | 1.385* (1.382-1.388) |

| Factors predicting PD/PDA | |||

| Total Trauma-Exposed Sample (N=12,467) | Trauma-Exposed Men (n=4,666) | Trauma-Exposed Women (n=7,801) | |

| PTSDa | 1.601* (1.597-1.604) | 1.721* (1.714-1.729) | 1.580* (1.576-1.583) |

| Wave 2 age | 0.975* (0.975-0.976) | 0.977* (0.976-0.977) | 0.975* (0.975-0.975) |

| Sex (0=male, 1=female) | 1.424* (1.422-1.427) | -- | -- |

| Race/ethnicity (0=white, 1=nonwhite) | 0.927* (0.925-0.929) | 0.767* (0.764-0.770) | 0.976* (0.974-0.978) |

| Education (1: high school/GED)b | 0.740* (0.738-0.742) | 0.777* (0.773-0.781) | 0.728* (0.725-0.730) |

| Education (2: some college) | 0.835* (0.832-0.837) | 1.012* (1.007-1.017) | 0.781* (0.779-0.784) |

| Education (3: Bachelor’s degree) | 0.690* (0.688-0.692) | 1.000* (0.995-1.005) | 0.610* (0.610-0.612) |

| Education (4: some graduate school) | 0.629* (0.627-0.631) | 0.802* (0.797-0.806) | 0.583* (0.581-0.586) |

| Number of traumatic event categories endorsed | 1.075* (1.074-1.075) | 1.108* (1.108-1.109) | 1.073* (1.073-1.073) |

| Major Depressive Disoraer (MDD) | 2.105* (2.101-2.109) | 2.197* (2.189-2.204) | 1.998* (1.994-2.002) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | 1.868* (1.864-1.871) | 1.931* (1.924-1.939) | 1.856* (1.852-1.860) |

| Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) | 1.951* (1.947-1.955) | 1.918* (1.911-1.926) | 1.979* (1.974-1.983) |

Note: Hazard ratios presented with 95% contiaence intervals

p<.001;

Time-dependent covariate;

Reterence group = 0: “less than high school”

Figure 1.

Associations between panic disorder (PD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

A diagnosis of PTSD was associated with a 60% increased chance of developing PD/PDA, above and beyond the effect of the covariates. The association between PTSD and subsequent onset of PD/PDA was stronger for men compared to women (test of gender comparison: Z=57.41, p<.01). Men with compared to without PTSD evidenced a 72% greater chance of developing PD/PDA, whereas women with compared to without PTSD evidenced a 58% increased chance of developing PD/PDA.

We then assessed whether there were differences in magnitude for PD/PDA predicting PTSD compared to PTSD predicting PD/PDA. Contrary to expectation, the association between PTSD and subsequent PD/PDA was significantly greater than the association between PD/PDA and subsequent PTSD (test of comparison: Z=151.39, p<.01). The same effect was detected for men (Z=9.96, p<.01) and women (Z=178.81, p<.01), although the difference in effect size was more pronounced for women compared to men. Finally, to evaluate whether sex differences in the total sample models were better accounted for by trauma type, models were re-run with categories of worst traumatic event (dummy coded 0 and 1) entered as covariates in the models. Neither the magnitude nor direction of effect changed with respect to the role of sex in the models or the respective associations between PD/PDA and PTSD, suggesting that sex differences likely are not reflecting differences in propensity for different types of trauma exposure.

Discussion

The aim of this investigation was to determine the bidirectional association between PD/PDA and PTSD in a large, epidemiologic sample of trauma-exposed adults. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first of its kind to examine temporal ordering of PD/PDA and PTSD among community-dwelling individuals with a PTE history. Results of descriptive analyses indicated that ages of onset of PD/PDA and PTSD were similar, but that PTSD onset occurred, on average, slightly earlier than PD/PDA onset (approximately age 29 compared to age 35, respectively). Results of the Cox PH models identified bidirectional associations, whereby PD/PDA significantly increased likelihood of developing PTSD, and PTSD significantly increased likelihood of developing PD/PDA. These findings are most consistent with past studies indicating the importance of common genetic and environmental vulnerabilities in understanding risk for co-occurring PD/PDA and PTSD [18–21].

Although prior theoretical and empirical studies have suggested a potentially causal role of panic psychopathology in relation to PTSD [14; 15], presumably by way of peri-traumatic panic attacks strengthening fear conditioning processes [8; 13], the current study did not find support for this model when considering this more severe form of panic psychopathology (e.g., full diagnosis of PD/PDA). In fact, a stronger association was evidenced for PTSD predicting PD/PDA compared to the reverse. Given that panic attacks are known to convey general risk for psychopathology, broadly defined (e.g., Goodwin et al., 2004), future studies would benefit from evaluating bidirectional associations between panic attacks and PTSD in epidemiological samples. It may be the case that different factors promote risk for panic attacks compared to PD/PDA, and that panic attacks compared to PD/PDA convey risk for different conditions.

While our findings are most consistent with a common liability model of comorbid PD/PDA and PTSD, other etiologic models of this relationship may be operating and investigation of multiple etiological pathways to comorbid PD/PDA-PTSD is needed. Additionally, studies of specific risk mechanisms linking PD/PDA and PTSD are needed, such as investigations of genetic and environmental factors underlying fear conditioning processes, as well as subjective and physiological reactivity to interoceptive cues (e.g., change in heart rate) [23]. Examining the role of cognitive risk factors (e.g., anxiety sensitivity) relevant to both disorders also would be fruitful [27; 28]. Further, it is possible that a different pattern of findings would emerge for nonclinical panic attacks, particularly peri-traumatic panic attacks, and PTSD; however, due to high rates of missing age of onset data for panic attacks among individuals without full PD/PDA, we were not able to examine these associations within the current investigation.

Our data indicate that there are significant sex differences in the relationships between PD/PDA and PTSD. Specifically, although women were more likely than men to meet criteria for either disorder, men had stronger associations between these disorders relative to women, particularly with regard to PD/PDA predicting PTSD. It may be that men who met PD/PDA had more severe symptomology than women, consistent with different gender thresholds for meeting diagnostic criteria. Alternatively, it may be the case that the observed sex differences in the relationship between PD/PDA and PTSD are better explained by differences in trauma characteristics, such as type of trauma (e.g., interpersonal versus accidental) [36]; however, the current follow-up analyses did not support this hypothesis. Men and women may also differ in their subjective and physiological reactions to trauma. Available research on the occurrence of peri-traumatic panic attacks has not found support for sex differences, or differences as a function of trauma type [9,15]. Finally, it is possible that sex moderates the factor structure of PTSD, which could influence the observed associations [37]. Further investigation of mechanisms accounting for sex differences in post-trauma reactions and patterns of comorbidity are needed.

There are three key clinical implications of our findings. First, it is possible that identification of common risk factors may inform the development of transdiagnostic prevention efforts. For example, a brief interoceptive exposure intervention after experiencing a PTE to decrease reactivity to symptoms of physiological arousal [38] may be beneficial for prevention of both PD/PDA and PTSD. Indeed, the cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) literature has been moving in the direction of transdiagnostic interventions (i.e., combined treatments), which are centered on the premise that phenotype-specific treatment manuals have shared components that can be distilled into one protocol to address symptoms across related conditions simultaneously [39]. Second, our results suggest that clinicians should be educated regarding the potential increased risk for PD/PDA associated with a PTSD diagnosis and vice versa, particularly among men. For example, assessment and monitoring of panic attacks and associated worry would be useful for patients presenting with trauma histories and/or PTSD symptoms. Finally, the highly comorbid nature of PTSD and PD/PDA and the increased risk that these disorders confer unto one another introduce the potential clinical utility of incorporating PD/PDA treatment principles into PTSD treatment and vice-versa. Given the pattern of sex differences observed in the present study, combined PD/PDA and PTSD treatment may be particularly suitable for male patients. Future research will be necessary to address combined treatment options and outcomes for individuals presenting comorbid PD/PDA and PTSD.

Our results should be interpreted in light of study limitations. First, trauma exposure and PTSD were only assessed at Wave 2, and lifetime diagnoses and self-reported ages of onset were used. As such, we are limited by our reliance on retrospective reporting. Additionally, as is often the case in the PTSD literature, Criterion A status and associated PTSD symptoms were only assessed for individuals’ self-identified “worst” traumatic events; therefore, temporal ordering of multiple Criterion A events could not be considered. Additionally, given that we only have information on PTSD symptoms related to the “worst” event, it is possible that individuals could have met criteria for PTSD based on an earlier trauma, in which case, effect size estimates could be skewed. Longitudinal studies are needed that are able to accommodate multiple trauma and sets of associated symptoms. Second, because of data limitations we were unable to assess the role of nonclinical panic attacks or panic reactivity in relation to PTSD; panic attacks are more common than PD/PDA and also are relevant to existing theoretical models of panic-PTSD. Therefore, future investigation of the longitudinal relationships between panic attacks and PTSD are needed. Similarly, we were not able to examine the role of potential vulnerability factors (e.g., HPA axis reactivity, anxiety sensitivity, interoceptive conditioning) accounting for comorbidity between PD/PDA and PTSD in this sample. Future investigations should incorporate measures of potential biological and environmental risk characteristics that could explain the observed patterns of comorbidity in the current study. Third, it is possible that individuals evidenced sub-clinical symptoms of these disorder prior to meeting full criteria. Future studies would benefit from evaluating patterns of onset of early symptoms, in addition to evaluating when individuals met full criteria for disorders. Finally, the current study focused on PD/PDA and PTSD comorbidity, due to theoretical and preliminary empirical evidence suggesting a potential causal role of panic psychopathology in the etiology of PTSD. As such, a full analysis of the patterns of onset of multiple anxiety and mood disorders was not within the scope of this project. Future investigations of temporal ordering of multiple axis I disorders would be useful for understanding more broad patterns of comorbidity among trauma-exposed individuals.

Acknowledgments:

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) was sponsored and conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Berenz is supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R00AA022385). Dr. Mezuk is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01-MH093642-01A). Dr. Amstadter is supported by a NARSAD Independent Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and from National Institutes of Health grants: R01AA020179, P60MD002256, and MH081056-01S1. Dr. Roberson-Nay is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (R01-MH101518 and administrative supplement), NIMH R21-106924, and a NARSAD Independent Investigator Award. Dr. York is supported by National Institute of Health grants P60MD002256 and R01 AG037986.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fourth Edition Washington, D.C.: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71(4):692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25(3):456–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McFarlane AC, Van Hooff M. Impact of childhood exposure to a natural disaster on adult mental health: 20-year longitudinal follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195(2):142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E et al. . Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52(12):1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meewisse M, Olff M, Kleber R et al. The course of mental health disorders after a disaster: Predictors and comorbidity. J Trauma Stress 2011;24(4):405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falsetti SA, Resnick HS. Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD with comorbid panic attacks. J Contemp Psychother 2000;31:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Pitman RK et al. The panic attack-posttraumatic stress disorder model: applicability to orthostatic panic among Cambodian refugees. Cogn Behav Ther 2008;37(2):101–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falsetti SA, Resnick HS. Frequency and severity of panic attack symptoms in a treatment seeking sample of trauma victims. J Trauma Stress 1997;10:683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leskin GA, Sheikh JI. Lifetime trauma history and panic disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Anxiety Disord 2002;16(6):599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL et al. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol 2001;110:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkonigg A, Kessler RC, Storz S, Wittchen H-U. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: Prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;101:46–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones JC, Barlow DH. The etiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 1990;10:299–328. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H et al. Psychological sequelae of the september 11 terrorist attacks in new york city. N Engl J Med 2002;346:982–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams RE, Boscarino JA. A structural equation model of perievent panic and posttraumatic stress disorder after a community disaster. J Trauma Stress 2011;24(1):61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P et al. Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54(11):1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45(8):1027–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chantarujikapong SI, Scherrer JF, Xian H et al. A twin study of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, panic disorder symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder in men. Psychiatr Res 2001;103(2-3):133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amstadter AB, Acierno R, Richardson LK et al. Posttyphoon prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder in a Vietnamese sample. J Trauma Stress 2009;22(3):180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenen KC, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J et al. A high risk twin study of combatrelated PTSD comorbidity. Twin Res 2003;6(3):218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Krueger RF et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the genetic structure of comorbidity. J Abnorm Psychol 2010;119(2):320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown TA, McNiff J. Specificity of autonomic arousal to DSM-IV panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther 2009;47(6):487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhtz C, Yassouridis A, Daneshi J et al. Acute panicogenic, anxiogenic and dissociative effects of carbon dioxide inhalation in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). J Psychiatr Res 2011;45(7):989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wichmann S, Kirschbaum C, Böhme C et al. Cortisol stress response in posttraumatic stress disorder ,apnic disorder, and major depressive disorder patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017;83:135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall GN, Miles JN, Stewart SH. Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD symptom severity are reciprocally related: Evidence from a longitudinal study of physical trauma survivors. J Abnorm Psychol 2010;119(1):143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benitez CI, Shea MT, Raffa S et al. Anxiety sensitivity as a predictor of the clinical course of panic disorder: a 1-year follow-up study. Depress Anxiety 2009;26(4):335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall-Berenz EC, Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO et al. Multimethod study of distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity in a trauma-exposed community sample. J Trauma Stress 2010;23(5):623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: a review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychol Bull 2010;136(4):576–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng EJ, Hiatt EL, McClair V et al. Efficacy of posttraumatic stress disorder treatment for comorbid panic disorder: A critical review and future directions for treatment research. Clin Psychol Science and Practice 2013; 20(3): 268–284. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Introduction to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health 2006;29:74–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 2008;92(1-3):27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox J Cox proportional-hazards regression for survival data In: Fox R, editor. An R and S-PLUS companion to applied regression. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodwin RD, Lieb R, Hoefler M, Pfister H, Bittner A, Beesdo K, & Wittchen HU (2004). Panic attack as a risk factor for severe psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 2207–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. 2008:37–85. doi: 10.1037/1942-9681.S.1.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frankfurt SB, Armour C, Contractor AA, Elhai JD. Do gender and directness of trauma exposure moderate PTSD’s latent structure? Psych Res 2016;245:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt NB, Eggleston AM, Woolaway-Bickel K et al. Anxiety Sensitivity Amelioration Training (ASAT): A longitudinal primary prevention program targeting cognitive vulnerability. J Anxiety Disord 2007;21(3):302–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown AB, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Diagnostic comorbidity in panic disorder: Effect on treatment outcome and course of comorbid diagnoses following treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]