Abstract

Purpose:

Cannabis use is increasing due to recent legislative changes. In addition, cannabis is often used in conjunction with alcohol. The airway epithelium is the first line of defense against infectious microbes. Toll-like receptors (TLR) recognize airborne microbes and initiate the inflammatory cytokine response. How cannabis use in conjunction with alcohol affects pulmonary innate immunity mediated by TLRs is unknown.

Methods:

Samples and data from an existing cohort of individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUDs), along with samples from additional participants with cannabis use alone and with AUD were utilized. Subjects were categorized into the following groups: no alcohol use disorder (AUD) or cannabis use (Control) (n=46), AUD only (n=29), Cannabis use only (n=39) and AUD and Cannabis use (n= 29). The participants underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and airway epithelial brushings. We measured IL-6, IL-8, TNF and IL-10 levels in BAL fluid, and performed real time PCR for TLR1–9 on the airway epithelial brushings.

Results:

We found significant increases in TLR2 with AUD alone, cannabis use alone and cannabis use with AUD compared to control. TLR5 was increased in cannabis users compared to control, TLR6 was increased in cannabis users and cannabis users with AUD compared to control, TLR7 was increased in cannabis users compared to control, and TLR9 was increased compared to control. In terms of cytokine production, IL-6 was increased in cannabis users compared to control. IL-8 and IL-10 were increased in AUD only.

Conclusions:

AUD and cannabis use have complex effects on pulmonary innate immunity that promote airway inflammation.

Keywords: Toll like receptors, alcoholism, ethanol, marijuana, cigarette smoke, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα

INTRODUCTION

Cannabis is the most commonly used drug in people with alcohol use disorders (AUDs) (Falk et al., 2008). It is estimated that 25% of those with AUDs also use cannabis (Falk et al., 2008), with 9% diagnosed with both cannabis use disorder and AUD (Luczak et al., 2017). Cannabis consumers often drink heavily and use cannabis on the same day (Metrik et al.). It is expected that cannabis use will increase due to expanded legalization in several states. As of 2018, eight states have legalized recreational cannabis use, while 23 others have legalized medical marijuana use. It is not known how concomitant use of alcohol and cannabis affects pulmonary health.

It is known that heavy alcohol use alters airway inflammation. This is likely due to changes in Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression and function. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are expressed on airway epithelium, where they sense pathogen associated molecular patterns, and initiate the inflammatory cascade. We have previously demonstrated that AUDs alter airway epithelial TLR2 and TLR4 expression, with TLR2 being upregulated, while TLR4 is downregulated in subjects with AUDs (Bailey et al., 2015). Further, in bronchial washings from subjects with AUDs, the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 were increased (Bailey et al., 2015).

Very little is known about how cannabis use alone, and in conjunction with alcohol, affects pulmonary innate immunity and airway inflammation. Published reports indicate that cannabis smokers have more respiratory symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, sputum production and wheeze (Biehl and Burnham, 2015; Bloom et al., 1987; Ribeiro and Ind, 2016). These symptoms are often associated with increased airway inflammation. Indeed, bronchoscopic studies have shown increased airway inflammatory indices in cannabis smokers compared to tobacco smokers (Roth et al., 1998b). Very little is known about how cannabis exerts these inflammatory effects, and how that may interact with concurrent risky alcohol use.

We hypothesized that cannabis use increases airway inflammation through alterations in TLR expression, and that these changes could be modulated by concomitant alcohol use. In this study, we evaluated samples from existing cohorts of participants with AUD and controls, as well as samples from newly recruited cannabis users with and without AUDs. We measured the effect of cannabis with and without alcohol use on mediators of airway epithelial cell inflammation. We also examined changes in TLR expression and bronchial washing cytokines that could potentially affect baseline airway inflammation, and provide information regarding how the lung defends itself from infection under conditions of alcohol and cannabis co-exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Informed consent and recruitment

This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided written, informed consent before their participation in the study. The subjects were recruited in conjunction with the established Colorado Pulmonary-Alcohol Research Collaborative (CoPARC). The cohort was designed to investigate how unhealthy alcohol intake affects lung health. Surveys regarding cannabis use along with toxicology testing for cannabis have been performed since CoPARC’s inception. Additionally, with the legalization of recreational cannabis use in Colorado, cannabis users with and without AUDs have been prospectively recruited to the cohort. Subjects with AUDs only and AUDs with cannabis use were recruited between May 2012 and January 2016 at the Denver Comprehensive Addictions Rehabilitation and Evaluation Services center (CARES). Denver CARES is an inpatient alcohol detoxification center affiliated with Denver Health and Hospital System in Denver, Colorado. Within the same timeframe, healthy subjects without AUDs, and healthy cannabis users were recruited using approved print and electronic advertisements in Denver, Colorado and the surrounding area.

Alcohol use disorder definition and testing

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) questionnaire was administered to all groups to screen for hazardous patterns of alcohol consumption. With this well-validated tool, a score of 8 and above in men, or 5 and above in women, identifies an AUD, with a sensitivity of 50–90% and a specificity of ~80% (Reinert and Allen, 2002).

Inclusion Criteria

Subjects with AUDs were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria for study entry: 1) an AUDIT score ≥ to 8 for men or ≥ to 5 for women; 2) alcohol use within 7 days of enrollment; and 3) age greater than or equal to 21 years. Subjects with AUDs were approached for enrollment only after sobriety was confirmed. Subjects were classified as “without AUD” if the AUDIT score was <8 for men and <5 for women. Once admitted, all participants (AUD and non-AUD) completed a focused questionnaire regarding alcohol, tobacco, and drug use, along with a clinical evaluation including a history and physical exam, baseline laboratory testing, pulmonary function testing, chest radiographs, and urine toxicology screen that assessed for cannabis, methamphetamines, opioids, and cocaine.

Exclusion Criteria

In an effort to minimize the effects of potential comorbidities, we excluded subjects if they met any of the following medical criteria: 1. Liver disease (cirrhosis, or total bilirubin >2 mg/dl, or albumin <3.0 g/dl), 2. History of gastrointestinal bleeding, 3. Heart disease (ejection fraction <50%, history of myocardial infarction, or severe valvular dysfunction), 4. Renal disease (on dialysis, or has a serum creatinine > 2.0 mg/dl), 5. Lung disease (abnormal chest radiograph or spirometry), 6. Diabetes Mellitis, 7. Human Immunodeficiency Virus, 8. Current pregnancy, or 9. age >60 yrs (due to increased rates of asymptomatic comorbidities in these individuals). 10. Concurrent illicit drug use defined as use of cocaine, opiates, or methamphetamines by self-report or toxicology screen were excluded.

Cigarette Smoking and Cannabis use

Cigarette smoking history was assessed by self-report. We collected information about current smoking habits as well as pack-year histories. Likewise, cannabis history was collected by self-report, including years using cannabis. Drug use in all participants (AUD and non-AUD) was verified by urine drug testing in the University of Colorado Hospital’s clinical laboratory. Subjects were considered to be cannabis users if they had a positive urine screening test for cannabis or reported current cannabis consumption. The time since last cannabis use was not assessed. All subjects endorsed use of inhaled cannabis as their primary mode of cannabis exposure.

Sample collection and processing

Subjects fasted and refrained from smoking, drinking, or using cannabis for 12 hours prior to the bronchoscopy. Bronchoscopies on those with AUDs were performed within 7 days of the last alcoholic drink, and the average time since last drink was 72 hours. The bronchoscopies were performed in the inpatient Clinical and Translational Research Center at the University of Colorado Hospital using standardized protocols as previously described (Burnham et al., 2011). Bronchial brush samples were collected from the right mainstem bronchus. The entire brush was then immediately stored in an aqueous RNA stabilization solution (RNAlater, Invitrogen) at −80° C. A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was then performed in a subsegment of either the right middle lobe or the lingula. The bronchial washing component (first aliquot of BAL collected) was saved separately (−80° C) and used for cytokine measurement in this study. Two bronchoscopists performed these procedures using an identical protocol. Two assistants aided in all procedures who had been similarly trained in the procedure.

Real-time polymerase chain reactions (PCR)

Real time PCR was performed as previously reported (Bailey et al., 2015). Briefly, mRNA was extracted from airway epithelial cells collected by endobronchial brushings and stored immediately in RNAlater using the MagMax kit (Applied Biosystems). The quantity and quality of the RNA was evaluated using a nanodrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher). Using only the samples that had a 260/280 ratio of >1.8, 100ng of template RNA and 2.5µM random hexamers was used with the Taqman real-time PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) to synthesize cDNA. Real time PCR cocktails were prepared using 1X Taqman universal master mix (Applied Biosystems) and 18S ribosomal RNA as a housekeeping gene. The primers for the gene of interest were: (TLR1: Hs00413978; TLR2: Hs00152932; TLR3: Hs00152933; TLR4: Hs00152939; TLR5: Hs00152825; TLR6: Hs00271977; TLR7: Hs01933259; TLR8: Hs00152972; TLR9: Hs00370913; Applied Biosystems). The reactions were run as a duplex on the ABI Prism 7400 detection system. Raw cycle thresholds (CT) were normalized to the housekeeping gene using the delta-delta CT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). To ensure that there was no batch- to-batch variation in PCR results, all samples were run at the same time. If samples had been assayed previously, they were re-assayed alongside the other samples.

Cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

Human IL-6, IL-8 and TNFα were measured in bronchial washings using previously described sandwich ELISA methods (Bailey et al., 2015). We used the bronchial washings because they are most representative of the cytokines produced in the airway epithelium. Bronchial washings were available for 125 of the 143 subjects. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates were coated with the appropriate capture antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) overnight. The plates were washed and recombinant IL-6, IL-8 or TNFα standards were applied along with 200 l of undiluted samples in duplicate wells for 2h. The plates were washed and a secondary biotinylated antibody was applied for an additional 2h. The plates were washed and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated strept-avidin detection reagent for 20 min. before being developed using 3,3’,5,5’- tetramethylbenzidine substrate containing 0.003% hydrogen peroxide (R & D Systems). The reactions were terminated with sulfuric acid and plates were read at 450 nm in an automated ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA ). Values for cytokines measured in culture supernatants were normalized for total protein in the airway washing fluid measured using the Bradford assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). IL-10 was measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Limits of detectability for the assays were: 60 pg/mL, 125 pg/mL, 15 pg/mL, and 12 pg/mL for IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, and IL-10, respectively.

Statistical methods

GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA) was used to graph the data and perform statistical analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, the data is graphed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean.

The demographic data was analyzed using chi squared contingency testing and analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate. For the rest of the data, we used a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons to determine statistical significance. In all tests, a p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Demographic information

The participants were divided into 4 categories determined by the presence of AUD based on the AUDIT score and history of cannabis use: 1. No AUD and no cannabis use 2. AUD only 3. Cannabis use only and 4. AUD and cannabis use.

The demographic information is summarized in Table 1. The participants were aged 21–57, with no significant differences in age between the groups (p=0.08). All groups were predominantly male, ranging from 63–86% but there were not statistical differences between the groups (p=0.09). In terms of race, Native Americans were overrepresented in the AUD only and the AUD and cannabis groups (p=0.001). AUDIT scores were normal in the “no AUD” groups (2.4–3.0); and elevated in the “AUD” groups (27.5–28), as expected. There were no differences in AUDIT score between the “AUD only” and “AUD with cannabis use” (p=0.59) There was a higher percentage of current smokers in the AUD groups, but pack years were very similar between all groups ranging from 6.0–9.5 pack years (p=0.54). The cannabis users had similar years of use in both the cannabis alone and cannabis with AUD groups of 13–15 years (p=0.59). The BMIs were similar between all the groups (p=0.09), and did not indicate any evidence of malnutrition.

Table 1:

Demographic Information

| No AUD, no cannabis use n=46 |

AUD only n=29 |

Cannabis use only n=39 |

AUD and cannabis use n=29 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 39.3 ± 8.8 | 42.6 ± 5.5 | 36.1 ± 8.6 | 42.2 ± 7.9 | 0.08 |

| Sex (% male) | 63.0 | 86.2 | 79.5 | 86.2 | 0.09 |

| Race(%) | 0.001* | ||||

| —Caucasian | 67.4 | 20.7 | 53.8 | 44.8 | |

| — Hispanic or Latino | 13.0 | 37.9 | 15.4 | 13.8 | |

| — African American | 8.7 | 17.2 | 20.5 | 13.8 | |

| — Native American | 4.3 | 20.7 | 2.6 | 27.6 | |

| — Other | 6.5 | 3.4 | 7.7 | 0 | |

| AUDIT score (Mean ± SD) | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 27.5 ± 8.3 | 3.0 ± 2.15 | 28.7 ± 8.7 | 0.59# |

| % Current smokers | 35% | 62% | 30% | 62% | 0.008* |

|

Cigarette smoking (pack-years) (Mean ± SD) |

6.1 ± 10.7 | 9.5 ± 12.5 | 6.0 ± 12.4 | 7.7 ± 9.6 | 0.54 |

|

Years smoking cannabis (Mean ± SD) |

0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 13.8 ± 10.1 | 15.25 ± 12 | 0.59^ |

| BMI (Mean ± SD) | 28.4 ± 0.8 | 26.0 ± 1.0 | 26.0 ± 0.8 | 26.2± 0.8 | 0.09 |

p < 0.05

Comparing AUD only and AUD and cannabis group

Comparing the Cannabis use only group and the AUD and cannabis use groups

The participants were grouped into the following groups: without AUD and without cannabis use, AUD only, Cannabis use only, AUD and cannabis use. AUD=Alcohol use disorder SD=Standard deviation. Other race: Includes those that report mixed race, Asian, Pacific Islanders, or choose to not respond.

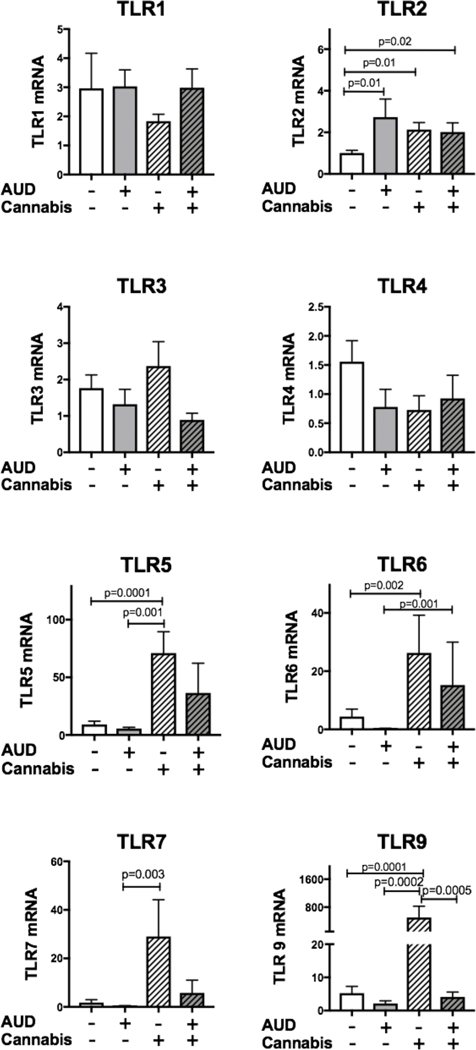

Airway epithelial TLR expression

We measured the mRNA expression of TLR1–9 in airway epithelial cell brushings in all participants (Figure 1). TLR8 was undetectable in all samples. We found no differences between the groups in TLR1, TLR3 and TLR4 expression.

Figure 1: TLR mRNA expression at baseline in those with AUDs and cannabis use.

Airway brushings were collected from subjects with no history of AUD or cannabis use, AUD, Cannabis use, or AUD and cannabis use. mRNA was extracted from the brushings and real time PCR for TLR1–9 was assayed. Each TLR was normalized to the housekeeping gene 18s ribosomal RNA. TLR8 was undetectable in all samples (Data not shown). Significant differences were seen in TLR2, TLR5, TLR6, TLR7 and TLR9.

TLR2, which senses gram-positive bacteria, was significantly increased from 1.00 ± 0.12 in the control group (No AUD, no cannabis use) to 2.73 ± 0.87 in the AUD only group (p=0.01), 2.13± 0.33 in the cannabis use only (p=0.01) and 2.02 ± 0.44 in AUD with cannabis use (p=0.02) groups. There was no additive or synergistic effect of cannabis use and AUD together. Both exposures increased TLR2 by the same magnitude.

TLR5 recognizes bacterial flagellin from invading motile bacteria such as Pseudomonas and Klebsiella. TLR5 was increased nearly 8-fold from the control group (9.19± 2.7) to the cannabis use only group (71.06 ± 18.5 p=0.0001). TLR5 was not significantly elevated in the AUD and cannabis group (36.49 ± 25.7).

TLR6 dimerizes with TLR2 to sense diacyl lipoproteins, which are part of the gram-positive cell wall. Compared to control, TLR6 was increased nearly 6-fold from control (4.4±2.5) to cannabis users (26.25 ± 12.9 p=0.002).

TLR7 recognizes single stranded RNA from viral genomes. TLR7 was increased 17-fold from control (1.79 ± 1.1) to cannabis users (29.05 ± 15.1, p=0.003). This increase was not seen in those with AUDs and cannabis use (5.75 ± 5.3)

TLR9 recognizes unmethylated DNA from viruses and bacteria. TLR9 was increased nearly 100-fold from control (5.25 ± 2.03) to cannabis users (504.2 ±323 p=0.0001). This increase was not seen in those with AUD and cannabis use.

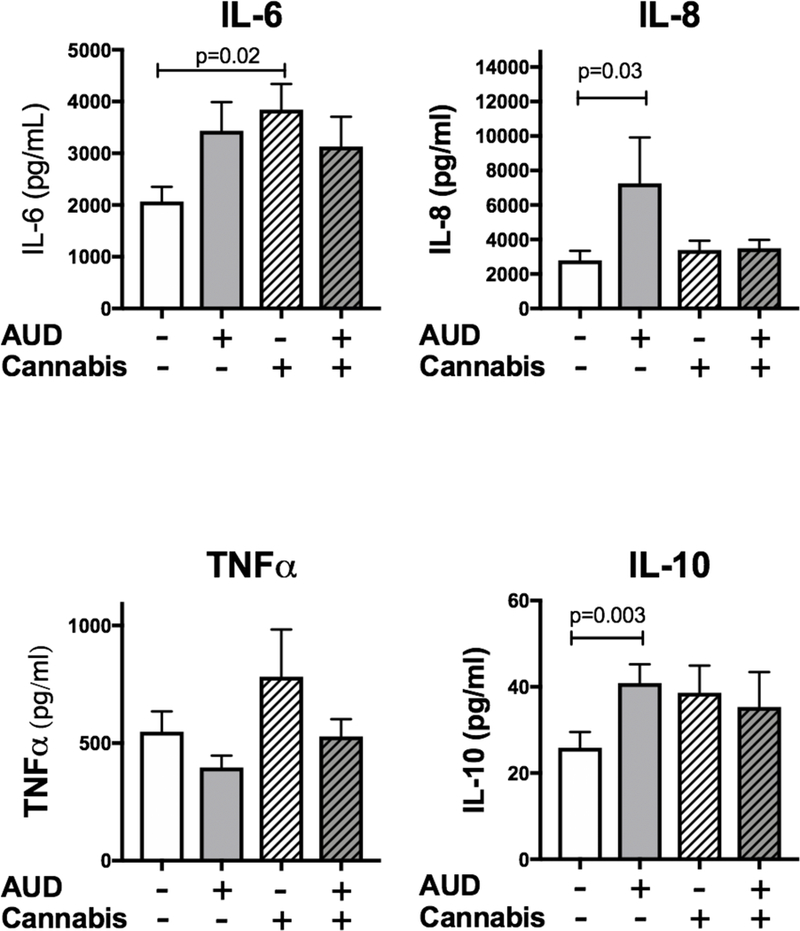

Cytokine levels in bronchial washings

To determine whether the alterations in TLR expression in those that use cannabis and have AUDs leads to shifts in airway inflammation at baseline, we measured cytokine levels in a subset of participants that had bronchial washings available (n=125). Cytokines measured included: IL-6, IL-8, TNFα and IL-10 (Figure 2). We found that IL-6 was significantly increased in cannabis users (3846 ± 492 pg/ml, p=0.02) compared to the control group (2069 ± 281 pg/ml). IL-8 was increased nearly 3-fold in those with AUDs (7259 ± 2663 pg/ml, p=0.03) compared to control (2791 ± 553 pg/ml). TNFα was similar in all groups, while IL-10 was increased in those with AUD only (40.9 ± 4.3 pg/ml, p=0.003) compared to control 25.9 ± 3.6).

Figure 2: IL-6 is increased in the bronchial washings of cannabis users.

Bronchial washings were available from a subset of subjects (without AUD and without cannabis use (n=40), AUD only (n=26), Cannabis use only (n=32), AUD and cannabis use (n=27)) and we measured the cytokines IL-6, IL-8, TNFα and IL-10. There was a significant increase (p=0.02) in IL-6 in the cannabis users compared to control. There was also a significant increase in IL-8 in those with AUDs (p=0.03) and an increase in IL- 0 with those with AUDs (p=0.003).

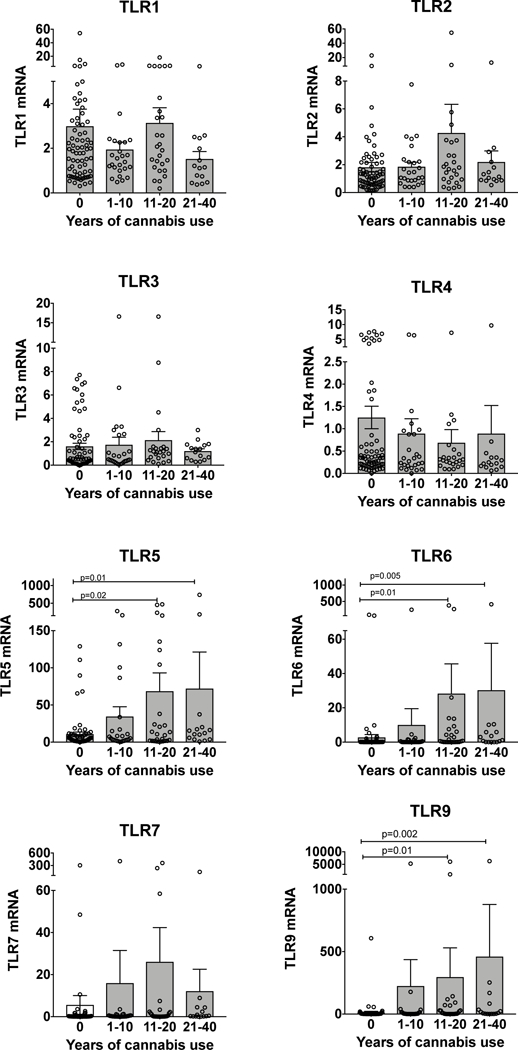

TLR expression as a function of years of self-reported cannabis use

We regrouped the subjects to determine whether TLR expression varied by the years of self-reported cannabis use. We used the categories of 0, 1–10, 11–20, and 21–40 years of cannabis use. The demographic information for these groups is shown in Table 2. There are no significant differences in age, sex, race, current smoking or smoking history or AUDIT scores between these groups. We found a significant increase in TLR5, TLR6 and TLR9 with increasing years of cannabis use compared to non-users (Figure 3). There was a trend towards increasing TLR5, TLR6 and TLR9 with increasing years of cannabis use.

Table 2: Demographic information.

All subjects were recategorized based on their years of cannabis use. SD=Standard deviation. Other race: Includes those that report mixed race, Asian, Pacific Islanders, or choose to not respond.

| Years of Cannabis use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 n=75 |

1–10 n=26 |

11–20 n=27 |

21–40 n=15 |

p-value | |

| Age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 40.6 ± 7.8 | 37.2 ± 9.0 | 36.7 ± 7.8 | 46.47 ± 6.9 | 0.057 |

| Sex (% male) | 72.0 | 80.7 | 85.2 | 80.0 | 0.51 |

| Race (%) | 0.93 | ||||

| — Caucasian | 50.7 | 53.8 | 44.4 | 46.6 | |

| —Hispanic or Latino | 20.0 | 11.5 | 22.2 | 13.3 | |

| —African American | 14.7 | 15.4 | 18.5 | 20.0 | |

| —Native American | 10.7 | 19.2 | 7.4 | 13.3 | |

| — Other | 4.0 | 0 | 7.4 | 6.7 | |

| % Current smokers | 45.3 | 61.5 | 29.6 | 33.3 | 0.12 |

| Cigarette smoking (pack-years) (Mean ± SD) |

7.4 ± 11.5 | 8.1 ±8.9 | 4.0 ± 8.0 | 9.2 ± 17.8 | 0.17 |

| AUDIT score (Mean ± SD) |

12.1 ± 13.4 | 14.5 ± 14.6 | 13.6 ± 14.1 | 13.7 ±13.9 | 0.86 |

| BMI (Mean ± SD) | 27.5 ± 5.5 | 25.5 ± 3.9 | 25.8 ± 4.8 | 27.5 ± 5.4 | 0.21 |

Figure 3: TLR5, TLR6 and TLR9 are increased in those that have used cannabis 11 years or longer.

We tested whether TLR1–9 levels vary based on the years of cannabis use. The mean is represented by the bar graph ± SEM. Each individual data point is represented by the open circles. There was a statistically significant increase in TLR5, TLR6 and TLR9 in those with 11 years of cannabis use or longer compared to non-users.

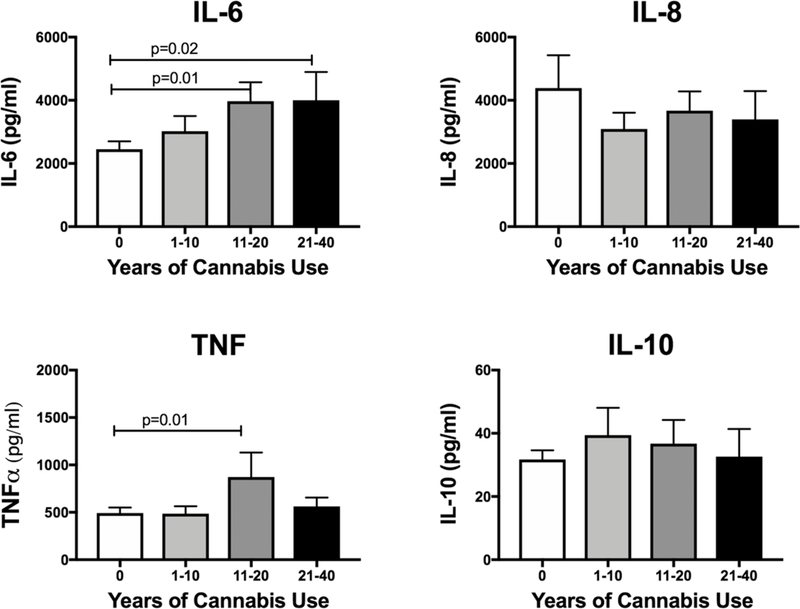

Cytokine levels as a function of years of self-reported cannabis use

We also tested whether cytokine levels varied based on years of self-reported cannabis use as described above. We noted a significant increase in IL-6 compared to non-users. There is a trend towards increasing IL-6 levels with longer duration of cannabis use. (Figure 4). This increase in IL-6 does not appear to be due to aging. We plotted bronchial washing IL-6 against age and found no increase, rather a trend towards decreasing levels with age (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 4: IL-6 is increased with longer duration of cannabis use.

We tested whether bronchial washing cytokine levels varied with the duration of cannabis use. Bronchial washings were not available for all subjects. The number available for each of the groups is as follows: 0 (n=66) 1–10 (n=24), 11–20 (n=23) 21–40 (n=12). Only IL-6 was increased compared to non-users. There is trend of increasing IL-6 with longer duration of cannabis use.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that AUD, cannabis use, and their combination have differing effects on pulmonary innate immunity. We measured differences in both TLR mRNA expression and cytokine levels in the bronchial washings. The airway epithelium is a target for both alcohol and cannabis use. During alcohol ingestion, alcohol freely diffuses from the bronchial circulation resulting in high levels of alcohol that form the basis of the breathalyzer test (Sisson, 2007). Likewise, the large airways experience a high concentration of cannabis smoke, up to ten times higher than the systemic concentrations. Large airway biopsies in habitual marijuana smokers reveal airway inflammation including basal cell hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, goblet cell hyperplasia, inflammation and basement membrane thickening (Roth et al., 1998a). How cannabis exerts these inflammatory effects is unknown, as is the interaction with risky alcohol use.

We have previously shown that AUD is associated with increases in TLR2 expression in the airways (Bailey et al., 2015), that was associated with increases in IL-8. TLR2 expression was also linearly related to AUDIT score (Bailey et al., 2015). In vitro data demonstrated that TLR2 was upregulated through a nitric oxide, cyclic GMP, dependent pathway (Bailey et al., 2010). The increased expression of TLR2 in vitro leads to excessive production of IL-8 in response to harmless stimuli (Bailey et al., 2009). In this study, we also measured an increase in TLR2 mRNA (Figure 1) and IL-8 (Figure 2) in those with AUDs. In addition, we have measured a significant increase in TLR2 mRNA in cannabis users with and without AUD.

Cannabis use was also associated with several alterations in TLR mRNA expression that were distinct from those found with AUD. TLR5, TLR6, TLR7 and TLR9 were significantly increased in cannabis users without AUD. Of these changes, the greatest fold change was found in TLR9, with an almost 100-fold increase in expression in cannabis users. This increase was not present in cannabis users that also had AUD. In addition, TLR5, TLR6 and TLR 9 levels were increased after 11 years using cannabis.

TLR9 plays an important role in the defense against viral infections. It initiates the inflammatory response which potentially protects against viral infection including production of IL-6 and TNFα. The mechanism of this upregulation of TLR9 is unknown. However, mitochondrial damage may play a role. Mitochondrial damage occurs after exposure to cannabis in vitro in lung cells (A549) (Sarafian et al., 2003) and in vivo in rats (Sarafian et al., 2006). Mitochondrial DNA (MtDNA) is an endogenous ligand for TLR9 in the lung (Zhang et al., 2014) (Gu et al., 2015) and systemically (Zhang et al., 2010). Murine intratracheal instillation of mitochondrial DNA, leads to activation of TLR9, and production of IL-6 and IL-10 in whole lung homogenate (Gu et al., 2015). So, cannabis use could potentially cause mitochondrial damage, leading to release of mitochondrial DNA, upregulation of TLR9 and increased IL-6 production. Further study of these mechanisms is required.

Like TLR9, TLR7 was upregulated in users of cannabis only. TLR7 also plays a role in pulmonary defense against viruses, through its recognition of viral RNA. There are very few in vitro or in vivo reports about how cannabis modulates TLR7 in the lung. However, there are data that demonstrate inhibition of the CB2 receptors decreases the expression of TLR7 following spinal cord injury (Adhikary et al., 2011). The increases in TLR 7 and TLR9, could also be explained if the cannabis users had a viral infection at the time of bronchoscopy, however, participants were carefully screened to avoid this confounder.

TLR5 was also increased in cannabis users, and seemed to be related to use of cannabis for longer than 11 years. TLR 5 senses flagellated bacteria such as Pseudomonas. Cannabis plants are frequently infected with the flagellated bacteria Xanthomonas (Jacobs et al., 2015), and Pseudomonas species (Fisk et al., 2009). Bongs used to smoke marijuana can also be infected with Pseudomonas (Kumar et al., 2018). These exposures could potentially activate airway epithelial TLR5, however, more research is needed to determine whether this is the case.

TLR6, which frequently dimerizes with TLR2 to signal inflammation was also increased in cannabis users and correlates with years of use. TLR6 often increases in conjunction with TLR2, its binding partner. TLR6, in this cohort seemed to increase more in relation to years of cannabis use than TLR2. This is likely due to the fact that TLR2 expression is closely linked to alcohol intake.

In cannabis users, bronchial washing IL-6 was significantly increased compared to control. IL-6 levels were also correlated with the number of years using cannabis. This is an interesting finding, because IL-6 has been reported to be decreased in other compartments in cannabis users. For instance, serum IL-6 levels are decreased in habitual marijuana users (Keen et al., 2014). Alveolar macrophages from habitual marijuana users, produce less IL-6 at baseline compared to non-users. (Baldwin et al., 1997). However, similar to our findings, cannabidiol exposure increased IL-6 mRNA in murine whole lung homogenate (Karmaus et al., 2013). Increased IL-6 at baseline could certainly contribute to the increased airway inflammation seen in chronic cannabis users.

Peripheral blood IL-10 has previously been shown to be increased in regular cannabis users (Pacifici et al., 2003). Although we saw a slight increase in bronchial washing IL-10 with cannabis use, it was not statistically significant. We did measure a statistically significant increase in bronchial washing IL-10 with AUD alone. This is consistent with animal studies reporting increased IL-10 in mice fed alcohol (D’Souza El-Guindy et al., 2007; Zisman et al., 1998).

Our work has significant limitations that diminish its broad applicability. First, using this design, we are unable to determine the mechanisms of how alcohol and cannabis use alters TLR expression and airway washing IL-6 levels. This work however, does inform future in vitro experiments to determine these mechanisms. In vitro experiments have the advantage of being able to separate alcohol, cannabis and smoking. Separating the effects of these exposures in poly-substance users is often difficult. For instance, there is a high number of current smokers in the population studied. People undergoing alcohol treatment have a very high prevalence of smoking (Falk et al., 2006), making recruiting subjects with AUDs without smoking very difficult. Tobacco use is a confounding variable in the current study that is difficult to control for due to the current study design. Prospectively controlled studies that examine the interaction of tobacco smoking and cannabis use might provide valuable insight that is not obvious from the current study. Another limitation of the work is that we do not know whether there were histological changes of the airway epithelium in the cannabis users such as goblet cell hyperplasia or squamous cell metaplasia in the airway brushings. It is possible that these cellular changes could alter TLR expression.

In conclusion, both alcohol and cannabis use have complex effects on pulmonary innate immunity. Both habits likely contribute to airway inflammation and alterations in innate immune defense by airway epithelial TLR expression and cytokine production. More research is necessary to understand its effects on human health.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

AUD and cannabis use have complex effects on pulmonary innate immunity that promote airway inflammation.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Dr. Harlan Sayles for advice regarding statistical analysis.

Grant Funding: NIAAA R24AA019661 to KLB, TAW & ELB, the Thoracic Foundation to ELB, NIA R01AG053553to KLB, and NIH/NCATS UL1 TR002535 to ELB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adhikary S, Li H, Heller J et al. (2011) Modulation of inflammatory responses by a annabinoid-2-selective agonist after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 28: 2417–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KL, Romberger DJ, Katafiasz DM et al. (2015) TLR2 and TLR4 Expression and Inflammatory Cytokines are Altered in the Airway Epithelium of Those with Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39: 1691–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KL, Sisson JH, Romberger DJ, Robinson JE, Wyatt TA (2010) Alcohol up-regulates TLR2 through a NO/cGMP dependent pathway. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34: 51–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KL, Wyatt TA, Romberger DJ, Sisson JH (2009) Alcohol functionally upregulates Toll-like receptor 2 in airway epithelial cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin GC, Tashkin DP, Buckley DM, Park AN, Dubinett SM, Roth MD (1997) Marijuana and cocaine impair alveolar macrophage function and cytokine production. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 1606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehl JR and Burnham EL (2015) Cannabis smoking in 2015: a concern for lung health? Chest 148: 596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JW, Kaltenborn WT, Paoletti P, Camilli A, Lebowitz MD (1987) Respiratory effects of non-tobacco cigarettes. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 295: 1516–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham EL, Phang TL, House R, Vandivier RW, Moss M, Gaydos J (2011) Alveolar macrophage gene expression is altered in the setting of alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 35: 284–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza El-Guindy NB, de Villiers WJ, Doherty DE (2007) Acute alcohol intake impairs lung inflammation by changing pro- and anti-inflammatory mediator balance. Alcohol 41: 335–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Yi H-Y, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S (2008) An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and drug use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Alcohol Research & Health 31: 100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Hsiao-Ye Y, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S (2006) An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders. Alcohol Research 29: 162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk ID, Gkatzionis K, Lad M, Dodd CER, Gray DA (2009) Gamma-irradiation as a method of microbiological control, and its impact on the oxidative labile lipid component of Cannabis sativa and Helianthus annus. European Food Research and Technology 228: 613–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Wu G, Yao Y et al. (2015) Intratracheal administration of mitochondrial DNA directly provokes lung inflammation through the TLR9-p38 MAPK pathway. Free radical biology & medicine 83: 149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JM, Pesce C, Lefeuvre P, Koebnik R (2015) Comparative genomics of a cannabis pathogen reveals insight into the evolution of pathogenicity in Xanthomonas. Frontiers in plant science 6: 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmaus PW, Wagner JG, Harkema JR, Kaminski NE, Kaplan BL (2013) Cannabidiol (CBD) enhances lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pulmonary inflammation in C57BL/6 mice. Journal of immunotoxicology 10: 321–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen L 2nd, Pereira D, Latimer W (2014) Self-reported lifetime marijuana use and interleukin-6 levels in middle-aged African Americans. Drug Alcohol Depend 140: 156–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AN, Soo CI, Ng BH, Hassan T, Ban AYL, Manap RA (2018) Marijuana “bong” pseudomonas lung infection: a detrimental recreational experience. Respirology case reports 6: e00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Khoddam R, Yu S, Wall TL, Schwartz A, Sussman S (2017) Review: Prevalence and co-occurrence of addictions in US ethnic/racial groups: Implications for genetic research. Am J Addict 26: 424–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J, Gunn RL, Jackson KM, Sokolovsky AW, Borsari B (2018) Daily Patterns of Marijuana and Alcohol Co-Use Among Individuals with Alcohol and Cannabis Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici R, Zuccaro P, Pichini S et al. (2003) Modulation of the immune system in cannabis users. JAMA 289: 1929–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF and Allen JP (2002) The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): a review of recent research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 26: 272–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro LI and Ind PW (2016) Effect of cannabis smoking on lung function and respiratory symptoms: a structured literature review. NPJ primary care respiratory medicine 26: 16071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth M, Arora A, Barsky S, Kleerup E, Simmons M, Tashkin D (1998a) Visual and pathologic evidence of injury to the airways of young marijuana smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 928–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MD, Arora A, Barsky SH, Kleerup EC, Simmons M, Tashkin DP (1998b) Airway inflammation in young marijuana and tobacco smokers. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 157: 928–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarafian TA, Habib N, Oldham M et al. (2006) Inhaled marijuana smoke disrupts mitochondrial energetics in pulmonary epithelial cells in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L1202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarafian TA, Kouyoumjian S, Khoshaghideh F, Tashkin DP, Roth MD (2003) A9- Tetrahydrocannabinol disrupts mitochondrial function and cell energetics. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 284: L298.- L306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson JH (2007) Alcohol and airways function in health and disease. Alcohol 41: 293–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JZ, Liu Z, Liu J, Ren JX, Sun TS (2014) Mitochondrial DNA induces inflammation and increases TLR9/NF-kappaB expression in lung tissue. Int J Mol Med 33: 817–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y et al. (2010) Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464: 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisman DA, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL et al. (1998) Ethanol feeding impairs innateimmunity and alters the expression of Th1- and Th2-phenotype cytokines in murine Klebsiella pneumonia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22: 621–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.