Abstract

Background:

Sixty percent of U.S. births are to multiparous women. Hospital-level policies and culture may influence intrapartum care and birth outcomes for this large population, yet have been poorly explored using a large, diverse sample. We sought to use national U.S. data to analyze the association between midwifery presence in maternity care teams and the birth processes and outcomes of low-risk, parous women.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using Consortium on Safe Labor data from low-risk parous women in either interprofessional care (n= 12,125) or non-interprofessional care centers (n=8,996). Unadjusted, adjusted (age, race, health insurance type), propensity-adjusted, and propensity-matched logistic regression models were used to assess processes and outcomes.

Results:

There was concordance in outcome differences across regression models. With propensity-score matching, women at interprofessional centers, compared to women at non-interprofessional centers, were 85% less likely to have labor induced (RR 0.15; 95% CI 0.14–0.17). The risk for primary cesarean birth among low-risk parous women was 36% lower at interprofessional centers (RR 0.64; 95% CI 00.52–0.79), while the likelihood of vaginal birth after cesarean for this population was 31% higher (RR 1.31; 95% CI 1.10–1.56). There were no significant differences in neonatal outcomes.

Conclusion:

Parous women have significantly higher rates of vaginal birth, including vaginal birth after cesarean, and lower likelihood of labor induction when cared for in centers with midwives. Our findings are consistent with smaller analyses of midwifery practice and support integrated, team-based models of perinatal care to improve maternal outcomes.

Keywords: Cesarean Section, Culture, Labor, Induced, Labor, Obstetric, Midwifery, Multiparity, Obstetrics, Oxytocin, Parturition

Sixty percent of U.S. births are to multiparous women, as are a similar proportion of maternal deaths.1 Despite this, labor processes and outcomes of parous women have been less thoroughly characterized than those of nulliparous women.2,3 Evidence suggests that the hospital in which an otherwise healthy woman gives birth is a factor independently affecting maternal and neonatal outcomes.4,5 Midwifery care has been associated with improved outcomes for healthy, low-risk women.6 While research suggests that the presence of midwives within a hospital system improves patient care outcomes, previous analyses have focused on a single-site7,8 or a single state.9 Additionally, these results came from samples of women with mixed parity or were only from nulliparous women. Of public health interest, the national overall cesarean rate is largely defined by the mode of birth for parous women, largely through repeat elective (no medical indication) cesareans.10

Though all major U.S. perinatal organizations agree that team-based models create an ideal culture for providing maternity care, the relationship between interprofessional care and outcomes has not been well characterized, especially in parous women.11 The purpose of this study was to use national U.S. data to analyze the association between maternity care teams with versus without midwives and the birth processes and outcomes of low-risk, parous women.

Methods

We selected our sample of low-risk, parous women from the dataset collected during the Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL) observational cohort study (2002–2008).12 This multi-site study was conducted at 12 clinical centers across the United States. The CSL dataset (N=228,438 births) included detailed information on birthing women, including demographics, medical history, reproductive and prenatal history, labor interventions, birth outcomes, postpartum and discharge information, and newborn information. In addition, the dataset contains information about individual centers, including level of obstetric and neonatal care and the composition of the maternity care team, including the presence of midwives, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, anesthesia personnel, and neonatologists. All data in CSL was collected at participating clinical centers using common codes for each predefined variable, then subjected to cleaning, recoding, logic checking, and validation studies by investigators as described elsewhere.12

The CSL contains two variables indicating whether centers employed both midwives and physicians (interprofessional) or only physicians (non-interprofessional). We also consulted Katerine Laughon Grantz, M.S., M.S., Principal Investigator of the CSL, to verify CSL variables on provider mix. Because the CSL dataset did not contain any variable that reliably indicated whether an individual’s labor care was provided by a midwife or physician, we organized comparisons between institutions that did or did not include midwives within the maternity care team. We obtained approval from both the Emory University Institutional Review Board and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for this secondary analysis.

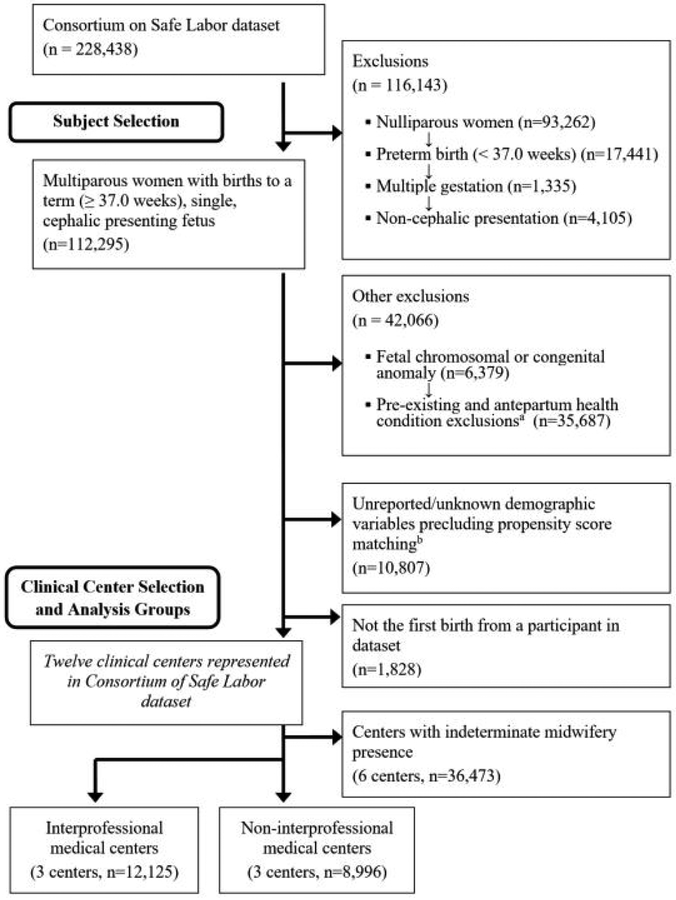

We selected a sample of healthy, parous women who gave birth to a single, cephalic-presenting fetus at or after 37 0/7 weeks gestation (Figure 1). Our rationale for focusing on a low-risk sample was to capture labor processes and outcomes in women eligible for either midwifery or obstetrical care. In addition, we excluded women with pre-existing and antepartum health conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, renal disease, gastrointestinal disease, depression, seizure disorders, thyroid disease, asthma, anemia, or HIV/herpes. By limiting our analyses to only healthy women, we reduced the confounding influence of variance in health conditions across centers in the dataset. We also excluded women carrying a fetus with known chromosomal or congenital anomalies.

Figure 1.

Diagram of patient selection.

aConditions excluded were diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, renal disease, gastrointestinal disease, depression, seizure disorders, thyroid disease, asthma, anemia, HIV/herpes.

bMaternal age, race, and health insurance type.

We excluded cases of women with no documented age, race, or health insurance type in the dataset, as these variables have been shown in previous studies to influence both cesarean rate and labor processes.10,13–15 To ensure independent samples, we only included the first documented birth to each parous woman in the CSL, excluding subsequent pregnancies and births in the dataset. Finally, we excluded 6 centers that had inconsistent documentation regarding whether midwives provided intrapartum care.

The main labor care processes we assessed included type of labor onset (i.e., spontaneous onset and trial of labor; induction of labor; cesarean without a trial of labor), rupture of membrane type (i.e., spontaneous or amniotomy), and the cervical examination at hospital admission. Birth outcome measures included the newborn’s gestational age at birth (early term 37 0/7 – 38 6/7 weeks; full term 39 0/7 – 40 6/7 weeks; late term 41 0/7 – 41 6/7 weeks; postterm ≥ 42 0/7), mode of birth, adverse maternal outcomes (maternal postpartum intensive care unit admission, maternal postpartum blood transfusion), neonatal intensive care unit admission, and adverse neonatal outcomes.

Adverse neonatal outcomes assessed included stillbirth or neonatal asphyxia, seizure, intracranial hemorrhage, paraventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, or death. Individually, these adverse neonatal outcomes occurred too rarely in the sample to be modeled. Therefore a composite was developed to assess differences between groups.8,14,16 We also analyzed neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission following birth. Since NICU admissions occurred more frequently than other adverse neonatal outcomes, we were also able to model NICU admission by interprofessional mix.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and Stata/SE 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). A critical alpha of 0.05 was used for determining statistical significance. Frequencies and percentages were used with categorical data; continuous data were assessed using median and associated percentiles. Comparisons of processes and outcomes between interprofessional and non-interprofessional centers were conducted using Mann-Whitney U for continuous data and likelihood ratio tests for categorical variables.

The propensity/predicted probability of a woman giving birth in an interprofessional center was assessed using her values for the confounding demographic characteristics of age, race, and health insurance type.23,24 We selected these three variables to calculate propensity scores because each was significantly different between the interprofessional and non-interprofessional groups in bivariate comparisons. Although another maternal demographic variable (highest educational level) was available in CSL, it was not usable when calculating propensity scores due to inconsistent completion among the medical centers included in this analysis.

Propensity score analysis is one form of causal inference, whereby relationships between exposures like midwifery presence and outcomes like cesarean birth are more rigorously analyzed by balancing the distribution of variables like race or age in the comparison groups, thereby decreasing confounding bias.17 The propensity value or score for each woman ranged from 0.00 to 1.00 with values closer to 0 suggesting a small probability of giving birth in an interprofessional center given the three demographic characteristics; values closer to 1.00 indicated a higher probability of giving birth in an interprofessional center.

Depending on the number of categories defining the study outcome, the effects of interprofessional presence (i.e., midwives and physicians) on each were generated and replicated using either binomial (for outcomes including type of membrane rupture and neonatal intensive care unit admission) or multinomial (for outcomes including gestational age at birth, labor onset, mode of birth) logistic regression models. Unmatched-case models included all women in the sample and used three different approaches.

Unadjusted logistic regression: This model included only the effect of interprofessional presence.

Adjusted models using observed covariates: This model estimated the effect of interprofessional presence after adjusting for maternal age, race, and health insurance type.

Adjusted models using the propensity scores: Rather than including the observed values for the demographic confounders, the effect of interprofessional presence was estimated after adjusting for the propensity (probability) values generated from those variables.

Finally, we built the most restrictive and conservative regression models to estimate the effect of interprofessional presence within a sample of women matched in a pairwise approach by their propensity values. With this approach, every woman who gave birth at an interprofessional medical center was matched with a woman who gave birth at a non-interprofessional center only when their propensity scores were within 0.001 of each other. This stringent approach resulted in matched pairs of cases on age, race, and insurance status.

Results

All centers included in this analysis were teaching hospitals and had 24-hour coverage by obstetricians, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, anesthesia personnel, and neonatologists. All centers had a level II or III NICU and were tertiary care centers for obstetric care. There was a mix of moderate to high annual birth volumes in medical centers from both the interprofessional group (center 1, 2810 births, center 2, 4172 births, and center 3, 6730 births) and non-interprofessional group (center 1, 3472 births, center 2, 4647 births, center 3, 6883 births) during 2006. Among the interprofessional care centers, midwives attended an average of 19.2% of births (center 1, 22.0%; center 2, 19.2%, center 3, 11.8%). Physicians attended all births at non-interprofessional medical centers.

In our unmatched sample (n = 21,121), women birthing at interprofessional centers were older and more likely to be white and/or have private insurance (Table 1). More women at interprofessional centers reached full or later-term gestation and, on average, had heavier neonates compared to non-interprofessional centers. Interprofessional centers had lower rates of intrapartum interventions such as amniotomy, induction of labor, and cesarean birth. By contrast, spontaneous labor and VBAC were more frequent at interprofessional centers. The average duration of time from hospital admission to birth was 1.5 hours shorter for women birthing at interprofessional centers. There were no significant differences between groups in NICU admission or composite adverse neonatal outcome score, nor on maternal postpartum blood transfusion or maternal postpartum intensive care unit admission.

Table 1.

Characteristics and birth outcomes of parous women with a single, cephalic presenting fetus at term gestation prior to propensity score matching in the Consortium on Safe Labor dataset (2002–2008), United States (N = 21,121).

| Interprofessional Centers (N = 12,125) n (%) or median [5th, 95th percentile] |

Non-Interprofessional Centers (N = 8,996) n (%) or median [5th, 95th percentile] |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Maternal age (y) | 29 [21–39] | 28 [19–39] | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 8588 (70.8) | 2823 (31.4) | <0.001 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1018 (8.4) | 3426 (38.1) | |

| Hispanic | 1393 (11.5) | 2221 (24.7) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 856 (7.1) | 473 (5.3) | |

| Other | 270 (2.2) | 53 (0.6) | |

| Health Insurance | |||

| Private | 10221 (84.3) | 4594 (51.1) | <0.001 |

| Public | 1812 (14.9) | 3994 (44.4) | |

| Self-pay/Other | 92 (0.8) | 408 (4.5) | |

| Birth Admission Information | |||

| Gestational age | |||

| Early term (37 0/7 – 38 6/7) | 3459 (28.5) | 3960 (44.0) | <0.001 |

| Full term (39 0/7 – 40 6/7) | 7353 (60.6) | 4576 (50.9) | |

| Late term (41 0/7 – 41 6/7) | 1169 (9.6) | 404 (4.5) | |

| Postterm (≥ 42 0/7) | 144 (1.2) | 56 (0.6) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 23.4 [18.3–35.3] | 23.9 [18.5–37.9] | <0.001 |

| Cervical dilatation (cm) | 5.0 [1.0–10.0] | 3.5 [1.0–8.0] | <0.001 |

| Cervical effacement (percent) | 80 [50–100] | 70 [20–100] | <0.001 |

| Fetal station | −2 [−3–1] | −2 [−4–0] | <0.001 |

| Birth Process and Outcome Information | |||

| Type of labor | |||

| Spontaneous onset and trial of labor | 8793 (72.5) | 4094 (45.5) | <0.001 |

| Induction and trial of labor | 2161 (17.8) | 3175 (35.3) | |

| Cesarean without trial of labor | 1171 (9.7) | 1727 (19.2) | |

| Amniotomy | 6375 (66.6) | 6334 (73.9) | <0.001 |

| Mode of birth | |||

| Vaginal - spontaneous | 9461 (78.0) | 6177 (68.7) | <0.001 |

| Vaginal - assisted | 281 (2.3) | 198 (2.2) | |

| Vaginal Birth after Cesarean (VBAC) | 645 (5.3) | 349 (3.9) | |

| Cesarean--repeat | 1421 (11.7) | 1844 (20.5) | |

| Cesarean--primary | 317 (2.6) | 428 (4.8) | |

| Indication for cesareans without trial of labor | <0.001 | ||

| Elective-no uterine scar | 11 (0.9) | 223 (12.9) | |

| Suspected macrosomia | 11 (0.9) | 24 (1.4) | |

| Non-reassuring fetal testing | 18 (1.5) | 11 (0.6) | |

| Placenta previa or abruption | 9 (0.8) | 18 (1.0) | |

| Uterine scar | 1056 (90.2) | 1408 (81.5) | |

| Otherc | 66 (5.6) | 43 (2.5) | |

| Indication for cesarean after trial of labor | <0.001 | ||

| Dystocia | 152 (32.1) | 154 (30.3) | |

| Abnormal or indeterminate fetal heart rate tracing | 140 (29.5) | 159 (31.3) | |

| Dystocia + abnormal or indeterminate fetal heart rate tracing (combined) | 35 (7.4) | 10 (2.0) | |

| Failed VBAC | 9 (1.9) | 8 (1.6) | |

| Elective (no medical indication) | 94 (19.8) | 146 (28.7) | |

| Otherd | 44 (9.3) | 31 (6.1) | |

| Admission to birth duration (h)e | 4.3 [0.5–16.1] | 5.8 [1.2–17.8] | <0.001 |

| Maternal postpartum blood transfusionf | 7 (0.4) | 51 (0.7) | NS |

| Maternal postpartum intensive care unit admissiong | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | NS |

| Maternal mortality | -- | -- | |

| Neonatal Information | |||

| Weight (infant) (kg) | 3.42 [2.75–4.18] | 3.32 [2.68–4.07] | <0.001 |

| Composite adverse neonatal outcomeh | 21 (0.2) | 27 (0.3) | NS |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 394 (3.2) | 333 (3.7) | NS |

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding. Denominator for some variables is different than column total due to missing/unknown values. Mann-Whitney U tests performed for continuous-level data comparisons due to non-normal distributions (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality < 0.001). Likelihood ratio tests were performed for categorical-level data comparisons. NS = Not statistically significant.

Values not reported for 51.3% (10,837) of women.

Limited to women with spontaneous labor onset and a trial of labor.

Documented in CSL dataset primarily as ‘other’, but also includes shoulder dystocia/history of shoulder dystocia (n=3).

Documented in CSL dataset primarily as ‘other’, but also includes failed labor induction (n=12).

Limited to women with a trial of labor.

Values not reported for 56.0% (11,769) of women.

Values not reported for 49.2% (10,385) of women.

Defined as stillbirth or neonatal asphyxia, seizure, intracranial hemorrhage, paraventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, or death.

In the matched sample (n = 10,542), neonates were more often born at full-or late-term and had heavier birth weights at interprofessional centers (Table 2). Women were admitted to the hospital with more advanced cervical dilations at interprofessional centers, and birth interventions such as amniotomy, induction of labor, and repeat cesarean birth were used significantly less often at interprofessional centers. More women achieved a VBAC at interprofessional centers. This difference was largely due to the use of pre-labor cesarean about half as often for women with a prior uterine scar (232/750, 30.9% at interprofessional centers vs. 680/1,091, 62.3% at noninterprofessional centers; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and birth outcomes of parous women with a single, cephalic presenting fetus at term gestation after propensity score matching in the Consortium on Safe Labor dataset (2002–2008), United States (N = 10,542).

| Interprofessional Centers (n = 5,271) n (%) or median [5th, 95th percentile] |

Non-Interprofessional Centers (n = 5,271) n (%) or median [5th, 95th percentile] |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Maternal age (y) | 31 [21–39] | 31 [21–39] | NS |

| Race | NS | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 2701 (51.2) | 2701 (51.2) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 990 (18.8) | 990 (18.8) | |

| Hispanic | 1148 (21.8) | 1148 (21.8) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 401 (7.6) | 401 (7.6) | |

| Other | 31 (0.6) | 31 (0.6) | |

| Health Insurance | NS | ||

| Private | 3895 (73.9) | 3895 (73.9) | |

| Public | 1341 (25.4) | 1341 (25.4) | |

| Self-pay/Other | 35 (0.7) | 35 (0.7) | |

| Birth Admission Information | |||

| Gestational age | <0.001 | ||

| Early term (37 0/7 – 38 6/7) | 1539 (29.2) | 2258 (42.8) | |

| ull term (39 0/7 – 40 6/7) | 3256 (61.8) | 2784 (52.8) | |

| Late term (41 0/7 – 41 6/7) | 444 (8.4) | 203 (3.9) | |

| Postterm (≥ 42 0/7) | 32 (0.6) | 26 (0.5) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 29.8 [23.8–41.2] | 28.9 [23.0–40.4] | <0.001 |

| Cervical dilatation (cm) | 5 [1.5–10] | 4 [1.0–8.5] | <0.001 |

| Cervical effacement (%) | 90 [50–100] | 80 [30–100] | <0.001 |

| Fetal station | −2 [−3–1] | −2 [−3–0] | <0.001 |

| Birth Process and Outcome Information | |||

| Type of labor | <0.001 | ||

| Spontaneous onset and trial of labor | 4601 (87.3) | 2825 (53.6) | |

| Induction and trial of labor | 426 (8.1) | 1707 (32.4) | |

| Cesarean without trial of labor | 244 (4.6) | 739 (14.0) | |

| Amniotomy | 2741 (62.7) | 3553 (71.1) | <0.001 |

| Mode of birth | <0.001 | ||

| Vaginal - spontaneous | 4273 (81.1) | 3851 (73.1) | |

| Vaginal - assisted | 102 (1.9) | 125 (2.4) | |

| Vaginal Birth after Cesarean (VBAC) | 329 (6.2) | 226 (4.3) | |

| Cesarean--repeat | 416 (7.9) | 857 (16.3) | |

| Cesarean--primary | 151 (2.9) | 212 (4.0) | |

| Indication for cesareans without trial of labor | NS | ||

| Elective, no uterine scar | 0 | 14 (1.9) | |

| Suspected macrosomia | 3 (1.2) | 14 (1.9) | |

| Non-reassuring fetal testing | 2 (0.8) | 4 (0.5) | |

| Placenta previa or abruption | 3 (1.2) | 7 (0.9) | |

| Uterine scar | 232 (95.1) | 680 (92.0) | |

| Otherc | 4 (1.6) | 20 (2.7) | |

| Indication for cesarean after trial of labor | <0.001 | ||

| Dystocia | 95 (34.8) | 84 (27.3) | |

| Abnormal or indeterminate fetal heart rate tracing | 76 (27.8) | 87 (28.2) | |

| Dystocia + abnormal or indeterminate fetal heart rate tracing (combined) | 25 (9.2) | 3 (1.0) | |

| Failed VBAC | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Elective (no medical indication) | 48 (17.6) | 113 (36.7) | |

| Otherd | 27 (9.9) | 16 (5.2) | |

| Admission to birth duration (h)e | 4.5 [0.5–15.3] | 5.7 [1.1–17.4] | <0.001 |

| Maternal postpartum blood transfusionf | 7 (1.0) | 12 (0.3) | NS |

| Maternal postpartum intensive care unit admissiong | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | NS |

| Maternal mortality | -- | -- | |

| Neonatal Information | |||

| Weight (infant) (kg) | 3.41 [2.75–4.18] | 3.36 [2.72–4.10] | <0.001 |

| Composite adverse neonatal outcomeh | 12 (0.2) | 14 (0.3) | NS |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 192 (3.6) | 172 (3.3) | NS |

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding. Denominator for some variables is different than column total due to missing/unknown values. Mann-Whitney U tests performed for continuous-level data comparisons due to non-normal distributions (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality < 0.001). Likelihood ratio tests were performed for categorical-level data comparisons. NS = Not statistically significant.

Values not reported for 23.9% (2,515) women.

Limited to women with spontaneous labor onset and a trial of labor.

Documented in CSL dataset as ‘other’.

Documented in CSL dataset primarily as ‘other’, but also includes failed labor induction (n=6).

Limited to women with a trial of labor.

Values not reported for 51.8% (5,459) women.

Values not reported for 43.5% (4,581) women.

Defined as stillbirth or neonatal asphyxia, seizure, intracranial hemorrhage, paraventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, or death.

Figure 2.

Mode of birth by provider mix for parous women with prior uterine scar in matched Consortium on Safe Labor sample (N=10,542), United States.

The duration of in-center time from admission to birth was 1.2 hours shorter for women birthing at interprofessional centers. There were no differences in rates of NICU admissions nor in composite adverse neonatal outcome between groups. As in the unmatched sample, both maternal postpartum blood transfusion and maternal postpartum intensive care unit admission were not different by center type.

There was concordance across unadjusted, adjusted (age, race, health insurance type), and propensity-adjusted logistic regression models, supporting the robustness of our findings (Table 3). Women at interprofessional centers were less likely to birth at early term but more likely to birth at late term or post-term. They were more likely to have a VBAC, but were less likely to have their labors induced, to have cesarean without a trial of labor, to have their amniotic sacs ruptured artificially, or to have primary cesarean birth than women in non-interprofessional centers. Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals from propensity-adjusted models are represented visually in Figure 3, where risks in the area to the left of the dashed line indicate outcomes that were less likely in centers with midwives and risks to the right of the dashed line indicate outcomes that were more likely in centers with midwives.

Table 3.

Risk ratios for labor interventions and birth outcomes among low-risk parous women receiving intrapartum care at interprofessional versus non-interprofessional medical centers in the Consortium on Safe Labor dataset (2002–2008), United States: Results of logistic regression analyses.

| Unmatched Case Models | Matched Case Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Unadjusted Model (N = 21,121) RR (95% CI) |

Adjusted Modela (N = 21,121) RR (95% CI) |

Propensity Score Adjusted Model (N = 21,121) RR (95% CI) |

Propensity Score Matched Model (N = 10,542) RR (95% CI) |

| Gestational age | ||||

| Early term (37 0/7 – 38 6/7) | 0.54 (0.51–0.58) | 0.59 (0.56–0.64) | 0.60 (0.56–0.64) | 0.58 (0.54–0.63) |

| Full term (39 0/7 – 40 6/7) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Late term (41 0/7 – 41 6/7) | 1.80 (1.60–2.03) | 1.75 (1.53–2.00) | 1.72 (1.50–1.97) | 1.87 (1.57–2.23) |

| Postterm (≥ 42 0/7) | 1.60 (1.17–2.18) | 1.37 (0.95–1.96) | 1.35 (0.95–1.92) | 1.05 (0.63–1.77) |

| Type of labor | ||||

| Spontaneous onset and trial of labor | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Induction and trial of labor | 0.32 (0.30–0.34) | 0.28 (0.26–0.30) | 0.28 (0.26–0.30) | 0.15 (0.14–0.17) |

| Cesarean without trial of labor | 0.32 (0.29–0.34) | 0.31 (0.29–0.35) | 0.32 (0.29–0.35) | 0.20 (0.17–0.24) |

| Rupture of membranes | ||||

| Spontaneousb | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Amniotomy | 0.71 (0.66–0.75) | 0.68 (0.63–0.73) | 0.68 (0.63–0.73) | 0.69 (0.63–0.75) |

| Mode of birth | ||||

| Vaginal - spontaneous | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Vaginal - assisted | 0.93 (0.77–1.11) | 0.92 (0.75–1.14) | 0.92 (0.75–1.14) | 0.74 (0.56–0.96) |

| Vaginal Birth after Cesarean | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | 1.31 (1.12–1.52) | 1.33 (1.14–1.55) | 1.31 (1.10–1.56) |

| Cesarean--primary | 0.48 (0.42–0.56) | 0.63 (0.53–0.75) | 0.64 (0.54–0.76) | 0.64 (0.52–0.79) |

| Cesarean--repeat | 0.50 (0.47–0.54) | 0.56 (0.51–0.61) | 0.56 (0.51–0.61) | 0.43 (0.39–0.50) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | ||||

| Yes | 0.87 (0.75–1.01) | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 1.12 (0.91–1.38) |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Non-interprofessional centers (physician providers only) are the reference group.

Adjusted for maternal age-race, and health insurance type.

Figure 3.

Adjusted risk ratios for selected labor interventions and outcomes by midwifery presence in hospital.

There were no significant differences in NICU admission rates in the unadjusted, adjusted (age, race, health insurance type), and propensity-adjusted models. Adverse neonatal outcomes occurred in only 0.2% of births (48 of 21,121), which was too rare to be modeled. Likewise, maternal postpartum ICU admission and blood transfusions were also too rare to be modeled.

Propensity score matching limited the analysis sample to 10,542 healthy, low-risk, parous women but allowed for the most restrictive and conservative regression modeling (Table 3). With this approach, women at interprofessional centers were less likely to birth at early term, but were more likely to birth at or after 41 weeks gestation, relative to women at non-interprofessional centers. At hospital admission, women had more advanced cervical dilations at interprofessional centers. There was a lower incidence of amniotomy, labor induction, primary cesarean, and cesarean before a trial of labor at interprofessional centers, while likelihood of VBAC was higher. There was no significant difference in risk of NICU admission.

Discussion

Low-risk parous women birthing at health care centers including both midwives and physician providers were more likely than women at non-interprofessional centers to have spontaneous labor and to achieve vaginal birth, even after a previous cesarean. Center-level mix of provider types was not associated with differences in maternal postpartum or neonatal outcomes in matched samples. Our analysis demonstrates the influence of system-level integration of midwives on labor processes and outcomes among low-risk multiparous women. Parous women are typically less susceptible to primary cesarean despite a range of management styles,10 but our analysis suggests that even this population is at risk for variations in quality with higher use of labor interventions within health care centers without midwives.

A major strength of our analysis is the CSL dataset which contains information on labor and birth from practice sites around the country serving heterogeneous populations.18 The size and diversity of this dataset strengthens the generalizability of our findings that the presence of midwives is important for birth outcomes in parous women.19 In addition, we selected a low-risk sample of parous women for our comparisons, as would be appropriate for management by either midwives or physicians. Finally, we conducted a series of regression analyses to estimate the effect of interprofessional presence within a sample of women, including the most restrictive and conservative regression model within a sample of women matched in pairs by their propensity values, and showed convergence of findings across models. Although propensity score matching is relatively novel in perinatal science investigations, this method strengthens our analysis by minimizing alternative explanations (confounding variables) for our findings.17

There is a growing body of literature demonstrating wide hospital-level variation in cesarean birth utilization that cannot be explained by patient level variability including maternal risk status.4,5,9,20 Driving this hospital variation are differences by individual clinician, hospital unit culture, hospital organizational culture and systems level factors that increase women’s risk for cesarean birth.21–23 One underexplored factor is the presence of midwives as part of intrapartum care teams. Although the presence of midwives in public health care systems of Europe, Canada, and the United Kingdom have been the subject of several investigations that were included in a recent systematic review,24 examination of the influence of midwifery presence on labor interventions and outcomes in the United States is limited to investigations in a single site,8 a single state/region,25 or in settings outside hospitals.26 Although the National Center for Health Statistics collects data on U.S. births attended by certified nurse midwives, information on labor interventions and outcomes is limited and at times of uncertain quality.27 Moreover, there is evidence that under-reporting of midwife-managed births on U.S. birth certificates limit the reliability of state, region, or country-level data.28

In health care systems no one works in isolation; teamwork leads to multiple and interrelated factors shaping care delivery.11 The presence of midwives may drive culture shifts within a hospital or health system. It is also possible that hospitals welcoming, attracting, and retaining midwives are culturally different compared to hospitals that do not have a midwifery presence. The Institute of Medicine released several initiatives to improve the culture of health care organizations including ‘To Err is Human’29 And ‘Crossing the Quality Chasm.30 All major U.S. perinatal organizations agree that team-based models of maternity create an ideal culture for providing women maternity care tailored to individual needs and personal preferences.11

We focused on processes and outcomes of intrapartum care for parous women in this study, which have been less thoroughly characterized than those of nulliparous women.8,31,32 Given the rarity of U.S. delivery by vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) and health risks that compound with each cesarean (accreta, percreta),33 health care systems factors that can effectively reach the goal of reducing use of cesareans and increasing VBAC warrant greater attention.

This investigation has several limitations. First, we excluded women with missing demographic information and from 6 centers with indeterminate midwifery presence. Unfortunately, although CSL was a large, federally-funded investigation designed to help investigators characterize contemporary labor, it was not designed to identify care by midwives for individual participants. However, when comparing mode of birth in our sample with women in these excluded groups, we saw no overall differences. In addition, we do not know whether patients in the midwifery presence group were cared for directly by midwives. Nor do we know the scope of practice of midwives in these medical centers. However, we saw significant differences by the presence of midwives in medical centers across a range of intrapartum outcomes, even after adjusting for maternal demographic factors. Another limitation regards neonatal outcomes; we did not have adequate sample size to assess differences by center in some of the more rare neonatal outcomes, like mortality. Because the CSL dataset was created to assess adverse neonatal outcomes at different points in labor progression, it contains many indicators of neonatal condition.18 We used these variables to construct neonatal adverse outcome scores and saw no differences by maternity care team composition on these scores or other, more common neonatal conditions in our matched models. The age of the CSL is another limitation and several clinical recommendations have occurred since the data was collected, including national efforts to reduce elective births prior to 39 weeks’ gestation34 or to quantify blood loss.35 Lastly, although the CSL was heterogenous, the hospitals were teaching institutions in large, urban areas, thus birth data from rural parts of the U.S. may be underrepresented in this study. However, given evidence that women have lower rates of cesarean birth when cared for in academic medical centers compared to community hospitals,36 it is possible that our findings of benefit for women laboring in academic medical centers with midwifery presence would be more pronounced among women laboring in rural community hospitals.

Future research in maternity health care services should address this with contemporary and more diverse nationally representative samples. In addition, future perinatal data sets should provide more information about the level of engagement of all maternity team members, including midwives, in the care of individual women. As well, we need more granular data regarding how labor care is provided and outcomes that are important to women; both will refine understanding of the potential role that interprofessional care may play in achieving optimal multiparous childbearing outcomes.

Overall, our analyses demonstrated that centers including midwives as intrapartum care providers less frequently used obstetric interventions such as labor induction and cesarean birth and more frequently accomplished VBAC delivery. It is not clear from our analysis whether these associations are due to the presence of the midwives themselves or the underlying culture at centers that hire and retain midwives. Our findings are consistent with prior state-level analysis reporting association between greater integration of midwives and significantly improved rates of physiologic birth as well as decreased incidence of perinatal interventions and adverse neonatal outcomes.37 Taken together, these findings provide greater support for facilitating midwifery care of low-risk women to promote optimal outcomes. Currently, only 8.8% of births in the U.S. are attended by nurse-midwives.10 Facilitation of greater access to midwifery care though policy, reimbursement, and hiring changes could improve population-level perinatal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING:

Dr. Nicole Carlson was supported by grant number K01NR016984 from the National Institute of Nursing Research during manuscript production.

Dr. Julia Phillippi was supported by grant number K08HS024733 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality during manuscript production. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Dr. Ellen L. Tilden was supported by grant number K12HD043488–14 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health, Oregon BIRCWH Scholars in Women’s Health Research Across the Lifespan.

Footnotes

STUDY INSTITUTION:

Based on analysis of Consortium on Safe Labor.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Nicole S. Carlson, Emory University Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Atlanta, GA..

Jeremy L. Neal, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville, TN..

Ellen L. Tilden, Oregon Health and Science University School of Nursing, Portland, OR..

Denise C. Smith, College of Nursing, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO..

Rachel B. Breman, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD..

Nancy K. Lowe, College of Nursing, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO..

Mary S. Dietrich, Schools of Nursing and Medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN..

Julia C. Phillippi, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville, TN..

References

- 1.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kominiarek M, VanVeldhuisen P, Gregory K, Fridman M, Kim H, Hibbard JU. Intrapartum cesarean delivery in nulliparas: Risk factors compared by two analytical approaches. J Perinatol. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrenthal DB, Jiang X, Strobino DM. Labor induction and the risk of a cesarean delivery among nulliparous women at term. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozhimannil KB, Arcaya MC, Subramanian S. Maternal clinical diagnoses and hospital variation in the risk of cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2015;70(2):67–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozhimannil KB, Law MR, Virnig BA. Cesarean delivery rates vary tenfold among US hospitals; reducing variation may address quality and cost issues. Health Affairs. 2013;32(3):527–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simms RA, Yelland A, Ping H, Beringer AJ, Draycott TJ, Fox R. Using data and quality monitoring to enhance maternity outcomes: a qualitative study of risk managers’ perspectives. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013:bmjqs-2013–002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson NS, Corwin EJ, Lowe NK. Labor intervention and outcomes in women who are nulliparous and obese: Comparison of nurse-midwife to obstetrician intrapartum care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(1):29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson NS, Corwin EJ, Hernandez TL, Holt E, Lowe NK, Hurt KJ. Association between provider type and cesarean birth in healthy nulliparous laboring women: A retrospective cohort study. Birth. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Relationship between hospital-level percentage of midwife-attended births and obstetric procedure utilization. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2018;63(1):14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake MS. Births: Final Data for 2016. Hattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics;2018, 67(1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Collaborative Practice. Collaboration in practice: Implementing team-based care. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(3):612–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, et al. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):326.e321–326.e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaki MN, Hibbard JU, Kominiarek MA. Contemporary labor patterns and maternal age. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1018–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yee LM, Costantine MM, Rice MM, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of labor management strategies intended to reduce cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):1285–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozhimannil KB, Shippee TP, Adegoke O, Vemig BA. Trends in hospital-based childbirth care: the role of health insurance. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(4):e125–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(6):513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tilden EL, Snowden JM. The Causal Inference Framework: A primer on concepts and methods for improving the study of well-woman childbearing processes. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Data and Specimen Hub, Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL) Study Page. 2018; or https://dash.nichd.nih.gov/study/2331. Accessed 6/10/18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillippi JC, Neal JL, Carlson NS, Biel FM, Snowden JM, Tilden EL. Utilizing datasets to advance perinatal research. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong JC, Kozhimannil KB, McDermott P, Saade GR, Srinivas SK. Comparing variation in hospital rates of cesarean delivery among low-risk women using 3 different measures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barber EL, Lundsberg LS, Belanger K, Pettker CM, Funai EF, Illuzzi JL. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spong CY, Berghella V, Wenstrom KD, Mercer BM, Saade GR. Preventing the first cesarean delivery: Summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1181–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmonds JK, O’Hara M, Clarke SP, Shah NT. Variation in cesarean birth rates by labor and delivery nurses. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46(4):486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:Cd004667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang YT, Attanasio LB, Kozhimannil KB. State scope of practice laws, nurse-midwifery workforce, and childbirth procedures and outcomes. Womens Health Issues. 2016. May-Jun;26(3): 262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nethery E, Gordon W, Bovbjerg ML, Cheyney M. Rural community birth: Maternal and neonatal outcomes for planned community births among rural women in the United States, 2004–2009. Birth. 2018;45(2): 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Declercq E Midwife-attended births in the United States, 1990–2012: Results from Revised Birth Certificate Data. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2015;60(1):10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biscone ES, Cranmer J, Lewitt M, Martyn KK. Are CNM-attended births in Texas hospitals underreported? J Midwifery Womens Health. Advance online publication. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 1999; or http://www.nap.edu/books/0309068371/html/. Accessed 6/10/18. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2000; or http://www.nap.edu/books/0309072808/html/. Accessed 6/10/18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neal JL, Lowe NK, Phillippi JC, et al. Likelihood of cesarean delivery after applying leading active labor diagnostic guidelines. Birth. 2017;44(2):128–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grobman WA, Bailit J, Lai Y, et al. Defining failed induction of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):122 e121–122 e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silver RM. Implications of the first cesarean: perinatal and future reproductive health and subsequent cesareans, placentation issues, uterine rupture risk, morbidity, and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(5):315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Commission Joint. Perinatal Care. Specifications Manual for Joing Commission National Quality Measures (v2016A) 2016; or https://manual.jointcommission.org/releases/TJC2016A/MIF0166.html. Accessed May 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conner SN, Tuuli MG, Colvin R, Shanks AL, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Accuracy of estimated blood loss in predicting need for transfusion after delivery. Am J Perinatol 2015;32(13):1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia FA, Miller HB, Huggins GR, Gordon TA. Effect of academic affiliation and obstetric volume on clinical outcome and cost of childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(4):567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vedam S, Stoll K, MacDorman M, et al. Mapping integration of midwives across the United States: Impact on access, equity, and outcomes. PloS one. 2018;13(2):e0192523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]