Abstract

Extracellular RNA (exRNA) has recently expanded as a highly important area of study in biomarker discovery and cancer therapeutics. exRNA consists of diverse RNA subpopulations that are normally protected from degradation by incorporation into membranous vesicles or by lipid/protein association. They are found circulating in biofluids, and have proven highly promising for minimally invasive diagnostic and prognostic purposes, particularly in oncology. Recent work has made progress in our understanding of exRNAs—from their biogenesis, compartmentalization, and vesicle packaging to their various applications as biomarkers and therapeutics, as well as the new challenges that arise in isolation and purification for accurate and reproducible analysis. Here we review the most recent advancements in exRNA research.

Keywords: Extracellular vesicles, RNA, Exosomes, Microvesicles, Vesicle biogenesis, Biomarkers, Noncoding RNA

1. Background

exRNA has emerged as an important source of biological information that represents the dynamic processes that occur intra- and intercellularly, in real time. exRNAs are released in a variety of subpopulations that vary amongst cell lines and are isolated via differing protocols. Here we discuss the potential of exRNAs in unraveling a new understanding of information trafficking in cells as well as the challenges in analyzing them in an accurate and reproducible fashion.

2. Biogenesis of exRNA and Role in Cell Biology

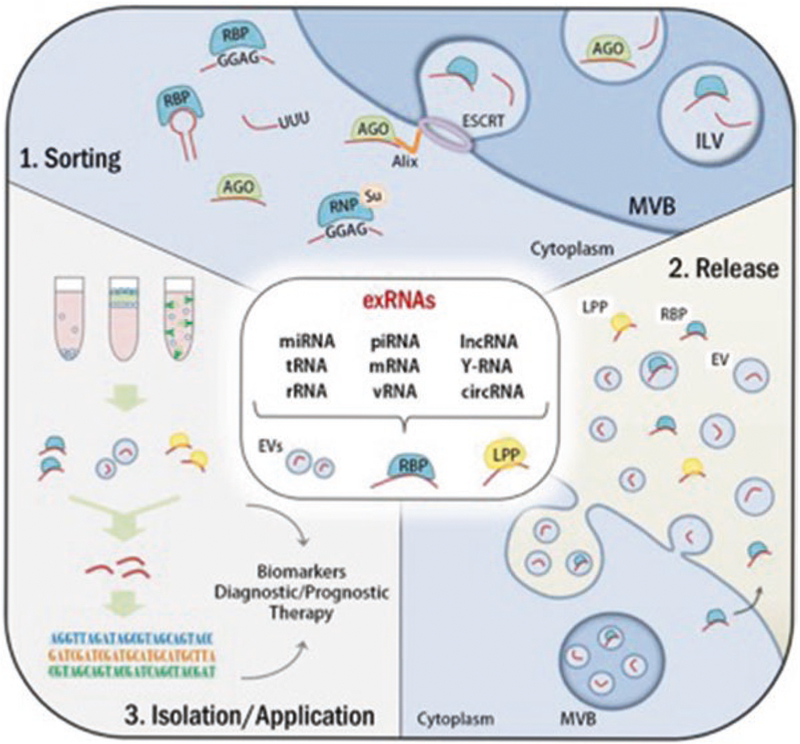

Most exRNA is protected from degradation by incorporation into membranous vesicles or association with lipids and/or proteins. Several subtypes of extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been described, including exosomes (<150 μm), microvesicles (200–500 μm), and oncosomes (1–10 μm) [1, 2]. Various biogenesis mechanisms are responsible for the formation of EVs. Whereas exosomes are shed through the multivesicular bodies of the endosomal pathway, microvesicles or ectosomes have been shown to bud off from the plasma membrane, and oncosomes can be released directly from tumor cell membranes. It is believed that the mechanism responsible for their formation influences their content, which consists of messenger RNA (mRNA), small noncoding (ncRNAs), DNA, proteins, and lipids. This content can be transferred to different cells and can mediate functional effects in these cells. Indeed, EVs have been shown to play a role in various biological processes, varying from establishing a body plan during development [3], to pathological processes as the formation of metastatic niches in cancer [4]. However, the extent to which RNA contents are responsible for these effects remains to be elucidated. EVs are generally regarded as a powerful source of biomarkers for various diseases, including glioblastoma [5–7], as they can be found in body fluids and their contents reflect the active status of their cells of origin (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sorting, release, and isolation/application of exRNAs. As shown in the central panel, several types of RNAs and fragments of RNAs have been detected extracellularly associated with EVs, RBP, and/or lipoproteins (e.g., HDL). (1) Sorting: RNAs sorting mechanisms into EVs. RBPs can bind to RNAs by recognizing specific motifs, sequence or structure and target them into EVs. RNA modification such as uridylation (U) has shown to be enriched in EVs when compared to the intracellular content. Argonaute proteins (AGO) are canonical miRNAs binding partners and are related to miRNAs sorting into EVs by mechanism that may involve Alix, an ESCRT member. hnRNPA2B1, an RNP, when modified by SUMO (Su) recognizes certain motifs in miRNAs and regulates their sorting into EVs. (2) Release: ExRNAs are released by the cells combined to RBPs (e.g., AGO), lipoproteins (e.g., HDL), or EVs. (3) Isolation/Application: Extracellular RBPs, lipoproteins, and vesicles can be isolated by using different techniques, such as differential ultracentrifugation, density gradient or immunocapture, and the RNAs can be purified for further sequencing or functional assays. exRNAs sources (EVs, RBP, lipoproteins) and exRNAs detection could be used as biomarkers or potential therapies. AGO: argonaute, EVs: extracellular vesicles, ESCRT: endosomal sorting complex required for transport, ILV: intralumenal vesicle, MVB: multivesicular bodies, RBP: RNA-binding protein, RNP: ribonucleoprotein

3. Compartments of exRNAs

exRNAs circulate in biofluids (e.g., blood, urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, breast milk, follicular fluid) as part of different compartments, which protect them from degradation by RNAses [8]. Namely, exRNAs are either encapsulated in EVs such as exosomes and larger vesicles [5], or bound in complexes with proteins such as the Argonaute 2 (Ago2) and high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) [9, 10]. Recent studies have shown that the profiles of exRNAs by compartment is different. For instance, while EVs are abundant in microRNAs (miRNAs), other types of RNAs are also detected, including small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), PlWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and tRNA fragments, YRNAs, ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), mitochondrial RNAs, and protein-coding RNAs [11–13]. On the contrary, the cargo of HDL:RNA complexes consist mainly of noncoding RNAs such as miRNAs, tRNA fragments, ribosomal RNAs, snoRNAs, and lncRNAs, but no protein-coding RNAs [14]. Lastly, Ago2 has binding affinity for miRNAs only [9, 14, 15].

4. Proposed Mechanisms of exRNA Packaging into EVs

Packaging of exRNAs in EVs is an active and orchestrated process that favors the sorting and enrichment of certain exRNAs in EVs, whereas it excludes others. To date, two major mechanisms have been characterized to regulate this process, an Ago2- and a chaperone-mediated mechanism. Recent studies have shown that Ago2 is a potent mediator of miRNAs sorting into EVs and that it can be regulated by the KRAS-MEK signaling pathway [16]. Other studies have shown that miRNAs with specific sequence motifs (i.e., GGAG and GGCU) were recognized and selectively sorted into EVs by the chaperone proteins heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2B1 (hnRNPA2B1) and RNA-interacting protein SYNCRIP [17]. In addition, the RNA-binding protein Y-box I (YBX-1) is suggested to be involved in the packaging of miRNAs and other exRNAs into EVs by recognizing secondary rather than primary RNA sequence motifs [18].

5. Overview of Extracellular mRNAs

Of all the subpopulations of exRNA, mRNA is one of the least abundant, accounting for a proportion of about 2% [19]. This low number of mRNA molecules poses the first major challenge in extracellular mRNA sequencing. Extracellular mRNA could be isolated from biological fluids such as blood, urine, saliva, or cerebrospinal fluid, or from in vitro cell culture supernatants. To date, RNA sequencing studies looking at extracellular mRNA focus on EV-associated mRNA. exRNA profiles, however, could vary when using different protocols for cell culture or methods for vesicle isolation [19, 20]. Since different subpopulations of exRNA vary in abundance between fractions after ultracentrifugation [20], EV isolation methods will clearly affect exRNA sequencing profiles. Furthermore, in cell cultures requiring fetal bovine serum (FBS), exRNA isolates are contaminated with FBS-derived exRNA, found in both the EV containing pellet and the supernatant after ultracentrifugation [20]. Up to 13% of FBS RNA reads can be mapped to the human or mouse genome, indicating that FBS-derived RNA significantly contributes to false-positive findings in both human and mouse exRNA sequencing studies [20]. Indeed, after re-analysis of publicly available exRNA sequencing datasets, in exosomes, roughly 2.6–17.2% of exRNA reads corresponded to bovine-specific transcripts [20]. For extracellular miRNA sequencing, the number of unique miRNAs had been shown to plateau at a sequencing depth of ten million reads [19]. For extracellular mRNA, however, optimal sequencing depth is unknown. Quantification of mRNA abundances requires normalization of their expression levels to well-established reference controls. Unfortunately, these controls have not yet been established for any of the exRNA subpopulations, including mRNA [19]. Additionally, for studies involving biomarker discovery for different disease conditions, a healthy control reference is currently lacking. Altogether, the field of extracellular mRNA sequencing faces considerable challenges, including the major concerns of low yield, FBS-derived mRNA contamination, and the lack of standardization of mRNA-seq library preparation.

6. Other Classes of exRNAs: microRNAs

miRNAs are small, noncoding post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression. They play important roles in diverse cellular processes, both in regulatory pathways and by acting as buffers to stochastic changes in transcription [21, 22]. It is estimated approximately 60% of all mRNAs are targeted by miRNAs [23]. miRNAs are highly processed; they are initially transcribed as components of long precursor transcripts, often many kilobases in length, called pri-miRNAs. These may be co-transcribed along with the mRNAs they regulate, or may be in distant locations of the DNA [24]. These pri-miRNAs form hairpin structures and are trimmed by the RNAse III, Drosha, to form a pre-miRNA that is exported from the nucleus in association with Exportin 5. When it enters the cytoplasm, its loop structure is cut by the endoribonuclease, Dicer. The mature miRNA, called the guide strand, forms one half of resulting RNA duplex, and is loaded into the miRNA silencing complex, miRISC, in association with the catalytically active component, Ago2 [25]. miRNAs suppress translation of mRNAs either by direct competitive blocking or by altering the stability of the target mRNA. This destabilization either occurs from shortening of the polyA tail or, if the miRNA has high complementarity with the target mRNA, Ago2 may directly cut the target [26–28]. miRNAs recognize their target mRNAs primarily through their seed sequences, a 6–8 nucleotide sequence near the 5′ end of the miRNA [29]. This region typically exhibits high complementarity with targets. In animals, the remainder of the miRNA does not require perfect complementarity to effectively suppress target mRNAs. Consequently, miRNAs are promiscuous regulators of many genes; each may act on dozens to hundreds of mRNAs [30]. Though miRNAs are abundant in the cytosol, they are also released into the extracellular environment either within vesicles or associated with low-density lipoproteins or other lipoproteins. As a consequence of this release, miRNAs are able to act on sites distant from their synthesis, are important mediators of cell-to-cell communication, and have demonstrated utility as biomarkers of both physiologic and pathologic processes [31–33].

6.1. Transfer RNAs

Transfer RNA (tRNA) is a 78–90 nucleotide RNA structure involved in the translation of mRNA to proteins, transporting amino acids to the ribosome where the anticodon of the tRNA binds to the complementary triplet mRNA codon and links the amino acids to form proteins [34]. However, an increasing amount of research shows that tRNA plays an important role in other cellular functions as well, influencing mRNA cleavage, inhibiting translation, and promoting morphological changes [35]. tRNA constitutes a large part of the RNAs found in exosomes, in larger proportions compared to other cellular RNAs [36–38]. This over-representation of tRNA has been observed in EVs shed by breast cells, bone marrow and adipose-mesenchymal stem cells, lung cells, semen, urine, and blood serum [37–40]. In contrast, EVs shed by melanoma cells appear to contain very little tRNA, while the proportion of tRNA in the microvesicles and apoptotic bodies shed by these cells is similar to that of the cellular cytoplasm [41]. The selection of tRNA found within an EV further indicates the discriminatory shedding of tRNA in EVs. One example was observed after the deep sequencing of EVs shed by mouse dendritic- and T cells: roughly seven times more reads of tRNA-Lys-AAA were observed in RNA derived from EVs compared to RNA recovered from intracellular space [36]. Aside from full-length tRNAs, EVs appear to harbor tRNA fragments (tRFs) in high concentrations [36, 37]. The exact mechanism of function of tRFs is unclear to date, but they are suspected to be involved in specific regulatory pathways [42]. For instance, the half of the tRNA-Gly containing the 5′ end suppresses protein synthesis, while smaller tRNA fragment inhibit translation nonspecifically [43, 44]. Similar increases of 5′ end tRNA halves in EVs have been recorded in breast, HeLa, and lung cell lines [37]. The reasons for which tRNAs and tRNA halves are concentrated in EVs, and whether those components are functionally transferred to cytosols of other cells remain to be known.

6.2. PIWI-Interacting RNAs

Among the small RNAs that guide gene regulation, piRNAs are the largest class of small ncRNA molecules expressed in animal cells, having prospects of hundreds of thousands of distinct piRNA species [45]. piRNAs are about 22–30-nt-long molecules that protect germ line cells from transposons, mobile genetic elements that threaten an organism’s genome. They guide PlWI-clade Ago proteins to complementary RNAs derived from transposable elements, where the PIWI proteins cleave transposon RNA, leading to silencing [46]. piRNAs are generated independently of Dicer from single-stranded precursors with the help of two RNP complexes [47]. Germ granules, specifically, pi-bodies, and a germ line analog of processing bodies, piP-bodies, are the cytoplasmic compartments where PIWI pathway components assemble [48]. Little is known about the extracellular presence of piRNAs. Although they had not been previously known to be widely present in biofluids, a 2016 study by Freedman et al. identified 144 small RNAs in circulation that mapped to piRNAs [45]. To distinguish piRNAs from other exRNAs, the study included two distinct reverse transcriptase experiments showing that piRNA RT-qPCR analyses were specific to piRNA 3′ modifications. Abundance of most piRNA species in B cells, neutrophils, peripheral mononuclear cells, platelets, and T cells were found to be nonsignificantly different from their abundances on plasma. However, B cells, neutrophils, platelets, and T cells had significant numbers of upregulated piRNA species as compared with plasma, while a majority of piRNA species were shown to be upregulated in red blood cells as compared with plasma. Interestingly, most piRNAs in exosomes were either not significantly different from downregulated as compared with plasma [45]. We do not yet know why piRNAs end up in EVs and whether they are functionally transferred to other cells.

6.2.1. YRNAs

YRNA is a very conserved class of small noncoding RNA [49] ranging from 84 to 113 nucleotides long in humans. It is highly abundant in cells, having a greater presence than tRNA and U6 snRNA. In extracellular fractions, including MVs, exosomes and RNPs, YRNAs have lower abundances than in cells, but are still more abundant than most miRNAs. Despite their high abundance levels, only four species exist in humans: Y1, Y3, Y4, and Y5. Furthermore, YRNAs have not been studied comprehensively, with less than 100 publications in PubMed. The lower stem domain of YRNAs was found to play a role in RNA quality control and degradation of misfolded RNAs by recruiting chaperone Ro60 and exoribonuclease PNPase [50]. The upper stem domain may participate in the initiation of chromosomal DNA replication [51]. YRNAs can be further processed to YRNA fragments, with the majority of modifications at the 5′ end. Although initially mistakenly thought of as miRNAs, these YRNA fragments are now known to be distinct entities. Their biogenesis is independent of Dicer, and they do not bind to Ago2 [52]. Functionally, YRNA fragments do not seem to silence target expression in a miRNA-like manner, as evidenced by a luciferase reporter assay [53]. The biological functions of YRNA fragments have not been clarified yet, but recent studies reported that they might be involved in cell damaging [54] and histone mRNA processing [55]. Interestingly, although YRNA fragments are less abundant than their full-length versions in cellular RNA, fragment abundance is higher than full-length abundance in extracellular fractions, and especially in RNP fractions where fragments contribute to approximately 20% of non-rRNA small RNA [56]. Further studies focusing on their biogenesis, secretion, and functions offer exciting new directions in RNA biology.

6.3. Other Noncoding RNAs

Apart from mRNAs, miRNAs, piRNAs, tRNAs, and YRNAs that are widely abundant in both cellular and extracellular spaces, the advent of next-generation sequencing revealed a broad spectrum of additional ncRNAs that are present in the acellular portions of biofluids [57, 58]. In the range of newly detectable exRNA, a significant expression of lncRNAs, small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), snoRNAs, and circular RNAs (circRNAs) were detected [19, 23, 58, 59]. lncRNAs are any nonprotein-coding RNAs with a length >200 nucleotides that lack a long open reading frame and/or do not show codon conservation. Since their relatively low evolutionary preservation and their low level of expression, some posited that they represented only “transcriptional noise” and/or redundant transcripts with no biological significance [60]. However, it is now clear that the lack of primary sequence conservation in lncRNAs does not indicate lack of function [61, 62]. The expression of TUC339, for example, a lncRNA that is selectively released in EV from hepatocellular cancer cells, has a foundational role in modulating tumor cell behavior [63]. snRNAs were found to be localized in EVs. Although their intracellular functions are noted and mainly related to RNA splicing, methylation, and pseudouridylation [64], their role in extracellular spaces is still poorly known. Appaiah, H.N. and colleagues, in 2011, identified U6, small nuclear RNA, that is upregulated in the sera of cancer patients [65]. Sequence analysis showed also that there were diverse collections of snoRNAs in human plasma-derived EV RNAs, among which C1orf213, LINC00324, and LOC388692 were the most abundant [58]. Despite the limited information available regarding their expression and function in human tissues, new examinations using an ion proton system for plasma of 40 individuals revealed that snoRNAs appear to primarily guide chemical modifications of other RNAs, managing alternative splicing and gene silencing [45]. In addition to linear RNA molecules described above, a specific type of ncRNA, circRNA, is generated from pre-mRNA with a back-splice mechanism, that connects the 3′ end and 5′ end of a transcript’s precursor to form a circle [66]. A circular structure makes circRNA more resistant to exonucleases than other types of RNAs, preventing from the characteristic degradation and digestion of molecules in extracellular spaces [66, 67]. Its hypothetical function involves downregulation of miRNAs by sequestering complementary miRNAs like a sponge [59].

7. Challenges in Isolating exRNA Subpopulations

Optimization of methods to isolate high-purity exRNA subpopulations and measuring quantity and integrity is a current technical challenge in exRNA research. The most studied exRNA subpopulation comprises the RNAs found in EVs. However, many biological effects associated with EV-RNA could also be caused by the presence of other RNA-containing components [15, 68], such as ribonucleoprotein complexes, viral particles, and lipoproteins (e.g., HDL and LDL). The source of these non-EV RNA-carriers could be the EV’s biological sample of origin or the fetal bovine serum in cell culture media [69, 70]. The yield and purity of EVs depend on the EVs isolation method, which consequently, defines the quantity and quality of EV-RNA [71–73]. Because current highly sensitive molecular techniques can detect small amounts of components in EV preparations, co-purification of non-EV contaminants generates a significant artifact for further RNA analysis [74–76].

EV isolation techniques are based on different biophysical properties of EVs, such as density, shape, size, and surface proteins and therefore enrich for different subpopulations of vesicles, although none of the methods recover a pure material containing only EVs [77]. These methods include differential ultracentrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, chromatography, filtration, polymer-based precipitation, and immunoaffinity. Ultracentrifugation is the most widely used method; however, the EV pellet can be contaminated with protein aggregates and viruses [78]. Density gradient centrifugation can be used in combination with ultracentrifugation to isolate highly purified EVs from other extracellular source of RNAs; however, this results in low yields. Lipoprotein may be co-isolated when the starting sample is plasma or serum [79]. Size exclusion chromatography consists of a size-based separation in a column. It promotes high EV recovery and removes most soluble contaminants, but other particles with similar pore-cutoff size may co-elute with the EVs [80]. Filtration can concentrate EVs and may remove soluble components, but similarly sized particles can contaminate the sample [81]. Precipitation techniques have high EV recovery rates, but also precipitate non-EV components [82]. Immunoaffinity uses antibodies against proteins found in EVs; thus, it can be used to isolate EV subpopulations. However, non-EV proteins might also be recovered. Indeed, the specific details of these purification procedures can differ significantly between different groups causing variability in the recovery of EVs, resulting in weaker detection of RNA in EVs and detection of RNA-carrying contaminants [79]. Several alternative techniques, many as commercially available kits, have been developed to improve EV purification, such as antibody-coated magnetic beads, affinity beads, novel precipitation (e.g., ExoQuick and Total Exosome Isolation) and filtration kits (e.g., PureExo), membrane affinity spin columns (e.g., ExoEasy), and microfluidics-based techniques (e.g., ExoChip) [83–88]. Particularly, ExoEasy kit allows recovering of both EVs and other soluble RNA-carriers separately [85]. Moreover, a combination of techniques has been described for purification of non-EV exRNA sources [9, 14, 89]. Despite the rapid growth of the exRNA research in the last few years, the field still needs standardized methods, both for isolation and characterization of exRNA subpopulations to enable successful exRNA applications as biomarkers and therapeutics.

8. exRNA as Biomarkers

exRNAs are contained and relatively stable within circulating vesicles in most biological fluids [90]. Among exRNAs, both miRNAs and piRNAs are the most highly enriched RNA species within extracellular vesicles, with a lower representation of long noncoding RNA, fragments of tRNA, YRNA and mRNA, among others [19]. exRNA-containing vesicles are present in most biofluids, consisting of a mixture of vesicles of different origin; either cells present in body fluids (e.g., blood [91], breast milk [92], and follicular fluid [93]) or cells contouring the space irrigated by body fluids (e.g., saliva, urine) [94]. Considering the advantage of easily collecting exRNA from biofluids in a noninvasive manner, many studies indicate that, in addition to having an important function in intercellular communication, exRNA could also be used as potential biomarkers as indicators of normal biological processes, as candidates for early stage diagnostic in patients at risk, and also as predictors of pathology recurrence after treatment. There is substantial evidence indicating that exRNA can be used both for diagnostic and prognostic purposes in the oncology field [95]. For instance, tumor-derived exRNA (e.g., hTERT mRNA and miR-141) can be detected in blood of prostate cancer patients, correlating with tumor size and malignancy [70, 96]. Among the tumors in the digestive system, a variety of serum miRNA is found expressed differentially in hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis. Additionally, exRNA in saliva is reported to be associated with pancreatic [97] and esophageal cancer [98]. As an additional example of exRNA used as biomarkers in the oncology field, miR-21, which is elevated in glioblastoma patients, has been shown to discriminate this from healthy patients [99]. Similarly, in cardiovascular disease, myocardial specific circulating miRNAs are significantly elevated in advanced heart failure, correlating with a concomitant increase in classical peptide biomarkers of myocardial damage like cardiac troponin I [100]. Furthermore, lncRNA could be considered as independent predictors of pathological cardiac remodeling and diastolic dysfunction in patients diagnosed with diabetes type 2 [101]. In addition to the oncology and cardiovascular fields indicated above, exRNA has also been described as potential biomarkers for pathological conditions in the nephrology [102] and neurology [95] fields, as well as in pregnancy [103, 104].

9. exRNA as Therapeutics for Cancer

To facilitate therapeutic delivery, exRNA can be packaged in stable natural carriers. Most studies have focused on using EVs as carriers for miRNA, siRNA, or other nucleic acids. Packaging anticancer nucleic acids in tumor-targeting EVs offers a novel method for cancer therapy. For example, Ohno et al. demonstrated that expressing GE11 peptide on the surface of EVs targets EGFR-positive tumor cells and that the delivery of a tumor suppressor miRNA, let-7a was able to inhibit breast cancer development in vivo [105]. In another study, microvesicle-encapsulated TGFβ1 siRNA was shown to inhibit murine sarcoma growth in vitro and in vivo [106]. The authors demonstrated that siRNA was associated with argonaute complexes in MVs, suggesting that MV packaged exRNA is stable and readily assembled for downstream gene silencing, as argonaute proteins are part of the RISC complex [107]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are being increasingly utilized as the source of EVs due to accessibility and therapeutic potency [108]. MSC-derived EVs were shown to be able to deliver anticancer small RNA in several cancer models, including osteosarcoma [110], hepatocellular carcinoma [110], bladder cancer [111], and glioblastoma multiforme. In these studies, miRNA or anti-miRNA-loaded EVs were able to inhibit tumor growth and migration, induce apoptosis, and render tumor cells more sensitive to chemotherapeutic agents. Although EVs are robust carriers of small RNA species, larger RNA species (such as mRNA) were also shown to be incorporated into these structures. The mRNA of a suicide gene was packaged in EVs that were able to inhibit tumor growth in a schwannoma model after the addition of the suicide drug [112]. However, it can be challenging to differentiate between the effects of mRNA or protein made from this mRNA in the producer cells. Taken together, the above examples suggest that exRNA packaged in EVs has therapeutic potential and once scalability and manufacturing of these complex drug carriers are established, they have an enormous potential in anticancer drug therapy.

10. Conclusion

As our knowledge of exRNA continues to rapidly expand, we are bound to learn more about vaguely understood exRNA subpopulations and their potential applications in medical diagnostics and novel therapeutic pipelines. As a lack of optimized and standardized methods to isolate high-purity exRNA subpopulations still challenges the field, future efforts must be made for the unification of these processes. Nevertheless, the promising field of exRNA research may soon revolutionize the way we look at cancer and related diagnostics in terms of quality, cost, efficiency, uniformity, and real-time analytic capabilities, as well as the future of targeted medicine in cancer therapy.

Acknowledgements

B.G. is an Edward R. and Anne G. Lefler Center Postdoctoral Fellow.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Di Vizio D et al. (2012) Large oncosomes in human prostate cancer tissues and in the circulation of mice with metastatic disease. Am J Pathol 181(5):1573–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minciacchi VR, Freeman MR, Di Vizio D (2015) Extracellular vesicles in cancer: exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 40:41–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanez-Mo M et al. (2015) Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles 4:27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa-Silva B et al. (2015) Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat Cell Biol 17(6):816–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skog J et al. (2008) Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol 10(12):1470–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen WW et al. (2013) BEAMing and droplet digital PCR analysis of mutant IDH1 mRNA in glioma patient serum and cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2:e109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balaj L et al. (2011) Tumour microvesicles contain retrotransposon elements and amplified oncogene sequences. Nat Commun 2:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lasser C et al. (2011) Human saliva, plasma and breast milk exosomes contain RNA: uptake by macrophages. J Transl Med 9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turchinovich A et al. (2011) Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 39(16):7223–7233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickers KC et al. (2011) MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol 13(4):423–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crescitelli R et al. (2013) Distinct RNA profiles in subpopulations of extracellular vesicles: apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and exosomes. J Extracell Vesicles 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasser C et al. (2017) Two distinct extracellular RNA signatures released by a single cell type identified by microarray and next-generation sequencing. RNA Biol 14(1):58–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellingham SA, Coleman BM, Hill AF (2012) Small RNA deep sequencing reveals a distinct miRNA signature released in exosomes from prion-infected neuronal cells. Nucleic Acids Res 40(21):10937–10949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michell DL et al. (2016) Isolation of high-density lipoproteins for non-coding small RNA quantification. J Vis Exp (117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arroyo JD et al. (2011) Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(12):5003–5008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cha DJ et al. (2015) KRAS-dependent sorting of miRNA to exosomes. Elife 4:e07197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villarroya-Beltri C et al. (2013) Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 controls the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes through binding to specific motifs. Nat Commun 4:2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shurtleff MJ et al. (2016) Y-box protein 1 is required to sort microRNAs into exosomes in cells and in a cell-free reaction. Elife 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan T et al. (2016) Plasma extracellular RNA profiles in healthy and cancer patients. Sci Rep 6:19413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei Z et al. (2016) Fetal bovine serum RNA interferes with the cell culture derived extracellular RNA. Sci Rep 6:31175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musilova K, Mraz M (2015) MicroRNAs in B-cell lymphomas: how a complex biology gets more complex. Leukemia 29(5):1004–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebert MS, Sharp PA (2012) Roles for microRNAs in conferring robustness to biological processes. Cell 149(3):515–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman RC et al. (2009) Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 19(1):92–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez A et al. (2004) Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res 14(10A): 1902–1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratt AJ, MacRae IJ (2009) The RNA-induced silencing complex: a versatile gene-silencing machine. J Biol Chem 284(27):17897–17901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N (2008) Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet 9(2):102–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eulalio A et al. (2009) Deadenylation is a widespread effect of miRNA regulation. RNA 15(1):21–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutvagner G, Zamore PD (2002) A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science 297(5589):2056–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen CB et al. (2007) Determinants of targeting by endogenous and exogenous microRNAs and siRNAs. RNA 13(11):1894–1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartel DP (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136(2):215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X et al. (2012) Secreted microRNAs: a new form of intercellular communication. Trends Cell Biol 22(3):125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vickers KC, Remaley AT (2012) Lipid-based carriers of microRNAs and intercellular communication. Curr Opin Lipidol 23(2):91–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melman YF et al. (2015) Circulating MicroRNA-30d is associated with response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure and regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis: a translational pilot study. Circulation 131(25):2202–2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharp SJ et al. (1985) Structure and transcription of eukaryotic tRNA genes. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 19(2):107–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hurto RL (2011) Unexpected functions of tRNA and tRNA processing enzymes. Adv Exp Med Biol 722:137–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolte-’t Hoen EN et al. (2012) Deep sequencing of RNA from immune cell-derived vesicles uncovers the selective incorporation of small non-coding RNA biotypes with potential regulatory functions. Nucleic Acids Res 40(18):9272–9285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tosar JP et al. (2015) Assessment of small RNA sorting into different extracellular fractions revealed by high-throughput sequencing of breast cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res 43(11):5601–5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baglio SR et al. (2015) Human bone marrow-and adipose-mesenchymal stem cells secrete exosomes enriched in distinctive miRNA and tRNA species. Stem Cell Res Ther 6:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M et al. (2014) Analysis of the RNA content of the exosomes derived from blood serum and urine and its potential as biomarkers. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 369(1652) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vojtech L et al. (2014) Exosomes in human semen carry a distinctive repertoire of small noncoding RNAs with potential regulatory functions. Nucleic Acids Res 42(11):7290–7304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lunavat TR et al. (2015) Small RNA deep sequencing discriminates subsets of extracellular vesicles released by melanoma cells—evidence of unique microRNA cargos. RNA Biol 12(8):810–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee YS et al. (2009) A novel class of small RNAs: tRNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs). Genes Dev 23(22):2639–2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivanov P et al. (2011) Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell 43(4):613–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sobala A, Hutvagner G (2013) Small RNAs derived from the 5′ end of tRNA can inhibit protein translation in human cells. RNA Biol 10(4):553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freedman JE et al. (2016) Diverse human extracellular RNAs are widely detected in human plasma. Nat Commun 7:11106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meister G (2013) Argonaute proteins: functional insights and emerging roles. Nat Rev Genet 14(7):447–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi R et al. (2016) Genetic and mechanistic diversity of piRNA 3′-end formation. Nature 539(7630):588–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chuma S, Pillai RS (2009) Retrotransposon silencing by piRNAs: ping-pong players mark their sub-cellular boundaries. PLoS Genet 5(12):e1000770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowalski MP, Krude T (2015) Functional roles of non-coding Y RNAs. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 66:20–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X et al. (2013) An RNA degradation machine sculpted by Ro autoantigen and noncoding RNA. Cell 153(1):166–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krude T et al. (2009) Y RNA functions at the initiation step of mammalian chromosomal DNA replication. J Cell Sci 122(Pt 16):2836–2845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicolas FE et al. (2012) Biogenesis of Y RNA-derived small RNAs is independent of the microRNA pathway. FEBS Lett 586(8):1226–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meiri E et al. (2010) Discovery of microRNAs and other small RNAs in solid tumors. Nucleic Acids Res 38(18):6234–6246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chakrabortty SK et al. (2015) Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of processed and functional RNY5 RNA. RNA 21(11): 1966–1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kohn M et al. (2015) The Y3** ncRNA promotes the 3′ end processing of hist one mRNAs. Genes Dev 29(19):1998–2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei Z, Batagov AO, Schinelli S, Wang J, Wang Y, El Fatimy R, Rabinovsky R, Balaj L, Chen CC, Hochberg F, Carter B, Breakefield XO, Krichevsky AM (2017) Coding and noncoding landscape of extracellular RNA released by human glioma stem cells. Nat Commun 8(1):1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeri A et al. (2017) Total extracellular small RNA profiles from plasma, saliva, and urine of healthy subjects. Sci Rep 7:44061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang X et al. (2013) Characterization of human plasma-derived exosomal RNAs by deep sequencing. BMC Genomics 14:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansen TB et al. (2013) Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 495(7441):384–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morris KV, Mattick JS (2014) The rise of regulatory RNA. Nat Rev Genet 15(6):423–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith MA et al. (2013) Widespread purifying selection on RNA structure in mammals. Nucleic Acids Res 41(17):8220–8236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnsson P et al. (2014) Evolutionary conservation of long non-coding RNAs; sequence, structure, function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840(3):1063–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kogure T et al. (2013) Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of a novel long noncoding RNA TUC339: a mechanism of intercellular signaling in human hepatocellular cancer. Genes Cancer 4(7–8):261–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maxwell ES, Fournier MJ (1995) The small nucleolar RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 64:897–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Appaiah HN et al. (2011) Persistent upregulation of U6:SNORD44 small RNA ratio in the serum of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 13(5):R86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen LL (2016) The biogenesis and emerging roles of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17(4):205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Memczak S et al. (2013) Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495(7441):333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turchinovich A, Burwinkel B (2012) Distinct AGO1 and AGO2 associated miRNA profiles in human cells and blood plasma. RNA Biol 9(8):1066–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shelke GV et al. (2014) Importance of exosome depletion protocols to eliminate functional and RNA-containing extracellular vesicles from fetal bovine serum. J Extracell Vesicles 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitchell PS et al. (2008) Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(30):10513–10518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brunet-Vega A et al. (2015) Variability in microRNA recovery from plasma: comparison of five commercial kits. Anal Biochem 488:28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li X, Mauro M, Williams Z (2015) Comparison of plasma extracellular RNA isolation kits reveals kit-dependent biases. Biotechniques 59(1):13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Royo F et al. (2016) Different EV enrichment methods suitable for clinical settings yield different subpopulations of urinary extracellular vesicles from human samples. J Extracell Vesicles 5:29497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Deun J et al. (2014) The impact of disparate isolation methods for extracellular vesicles on downstream RNA profiling. J Extracell Vesicles 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laurent LC et al. (2015) Meeting report: discussions and preliminary findings on extracellular RNA measurement methods from laboratories in the NIH Extracellular RNA Communication Consortium. J Extracell Vesicles 4:26533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanriverdi K et al. (2016) Comparison of RNA isolation and associated methods for extracellular RNA detection by high-throughput quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem 501:66–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gardiner C et al. (2016) Techniques used for the isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles: results of a worldwide survey. J Extracell Vesicles 5:32945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jeppesen DK et al. (2014) Comparative analysis of discrete exosome fractions obtained by differential centrifugation. J Extracell Vesicles 3:25011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yuana Y et al. (2014) Co-isolation of extracellular vesicles and high-density lipoproteins using density gradient ultracentrifugation. J Extracell Vesicles 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boing AN et al. (2014) Single-step isolation of extracellular vesicles by size-exclusion chromatography. J Extracell Vesicles 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vergauwen G et al. (2017) Confounding factors of ultrafiltration and protein analysis in extracellular vesicle research. Sci Rep 7(1):2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gamez-Valero A et al. (2016) Size-exclusion chromatography-based isolation minimally alters extracellular vesicles’ characteristics compared to precipitating agents. Sci Rep 6:33641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kanwar SS et al. (2014) Microfluidic device (ExoChip) for on-chip isolation, quantification and characterization of circulating exosomes. Lab Chip 14(11):1891–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Balaj L et al. (2015) Heparin affinity purification of extracellular vesicles. Sci Rep 5:10266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Enderle D et al. (2015) Characterization of RNA from exosomes and other extracellular vesicles isolated by a novel spin column-based method. PLoS One 10(8):e0136133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gallart-Palau X et al. (2015) Extracellular vesicles are rapidly purified from human plasma by PRotein Organic Solvent PRecipitation (PROSPR). Sci Rep 5:14664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shih CL et al. (2016) Development of a magnetic bead-based method for the collection of circulating extracellular vesicles. New Biotechnol 33(1):116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Puhka M et al. (2017) KeepEX, a simple dilution protocol for improving extracellular vesicle yields from urine. Eur J Pharm Sci 98:30–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Burwinkel B (2013) Isolation of circulating microRNA associated with RNA-binding protein. Methods Mol Biol 1024:97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E (2009) Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 9(8):581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schipper HM et al. (2007) MicroRNA expression in Alzheimer blood mononuclear cells. Gene Regul Syst Bio 1:263–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Karlsson O et al. (2016) Detection of long non-coding RNAs in human breastmilk extracellular vesicles: implications for early child development. Epigenetics:0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Machtinger R et al. (2017) Extracellular microRNAs in follicular fluid and their potential association with oocyte fertilization and embryo quality: an exploratory study. J Assist Reprod Genet 34(4):525–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dear JW, Street JM, Bailey MA (2013) Urinary exosomes: a reservoir for biomarker discovery and potential mediators of intrarenal signalling. Proteomics 13(10–11):1572–1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Quinn JF et al. (2015) Extracellular RNAs: development as biomarkers of human disease. J Extracell Vesicles 4:27495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.March-Villalba JA et al. (2012) Cell-free circulating plasma hTERT mRNA is a useful marker for prostate cancer diagnosis and is associated with poor prognosis tumor characteristics. PLoS One 7(8):e43470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xie Z et al. (2013) Salivary microRNAs as promising biomarkers for detection of esophageal cancer. PLoS One 8(4):e57502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xie Z et al. (2015) Salivary microRNAs show potential as a noninvasive biomarker for detecting resectable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 8(2):165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Akers JC et al. (2013) MiR-21 in the extracellular vesicles (EVs) of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): a platform for glioblastoma biomarker development. PLoS One 8(10):e78115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akat KM et al. (2014) Comparative RNA-sequencing analysis of myocardial and circulating small RNAs in human heart failure and their utility as biomarkers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(30):11151–11156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.de Gonzalo-Calvo D et al. (2016) Circulating long-non coding RNAs as biomarkers of left ventricular diastolic function and remodelling in patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep 6:37354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ben-Dov IZ et al. (2016) Cell and microvesicle urine microRNA deep sequencing profiles from healthy individuals: observations with potential impact on biomarker studies. PLoS One 11(1):e0147249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rodosthenous RS, Burris HH, Sanders AP, Just AC, Dereix AE, Svensson K, Solano M, Téllez-Rojo MM, Wright RO, Baccarelli AA (2017) Second trimester extracellular microRNAs in maternal blood and fetal growth: an exploratory study. Epigenetics 12(9):804–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tsochandaridis M, Nasca L, Toga C, Levy-Mozziconacci A (2015) Circulating MicroRNAs as clinical biomarkers in the predictions of pregnancy complications. BioMed Res Int 2015:294954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ohno S et al. (2013) Systemically injected exosomes targeted to EGFR deliver antitumor microRNA to breast cancer cells. Mol Ther 21(1):185–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang Y et al. (2014) Microvesicle-mediated delivery of transforming growth factor beta1 siRNA for the suppression of tumor growth in mice. Biomaterials 35(14):4390–4400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jinek M, Doudna JA (2009) A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature 457(7228): 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lai RC, Yeo RW, Lim SK (2015) Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 40:82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shimbo K et al. (2014) Exosome-formed synthetic microRNA-143 is transferred to osteosarcoma cells and inhibits their migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 445(2):381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lou G et al. (2015) Exosomes derived from miR-122-modified adipose tissue-derived MSCs increase chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol 8:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Greco KA et al. (2016) PLK-1 silencing in bladder cancer by siRNA delivered with exosomes. Urology 91:241.e1–241.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mizrak A et al. (2013) Genetically engineered microvesicles carrying suicide mRNA/protein inhibit schwannoma tumor growth. Mol Ther 21(1):101–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]