Abstract

Previous research implies that the extent of welfare state regime provision plays an important indirect role in the prevalence of loneliness in later life. The aim of this study was therefore to assess the association between quality of living conditions and level of social integration indicators and the absence of loneliness in five different welfare regimes. By incorporating welfare state regimes as a proxy for societal-level features, we expanded the micro-level model of loneliness suggesting that besides individual characteristics, welfare state characteristics are also important protective factors against loneliness. The data source was from the European Social Survey round 7, 2014, from which we analysed 11,389 individuals aged 60 and over from 20 countries. The association between quality of living conditions, level of social integration variables and the absence of loneliness was analysed using multivariate logistic regression treating the welfare regime variable as a fixed effect. Our study revealed that the absence of loneliness was strongly associated with individual characteristics of older adults, including self-rated health, household size, feeling of safety, marital status, frequency of being social, as well as number of confidants. Further, the Nordic as well as Anglo-Saxon and Continental welfare regimes performed better than the Southern and Eastern regimes when it comes to the absence of loneliness. Our findings showed that different individual resources were connected to the absence of loneliness in the welfare regimes in different ways. We conclude that older people in the Nordic regime, characterised as a more socially enabling regime, are less dependent on individual resources for loneliness compared to regimes where loneliness is to a greater extent conditioned by family and other social ties.

Keywords: Loneliness, Older people, Welfare regimes, Comparative research, ESS

Introduction

Previous research has shown that loneliness is associated with individual-level characteristics, such as gender, age, marital status and socio-economic status (de Jong Gierveld 1998; Pinquart and Sörensen 2001). Loneliness has also been associated with cultural factors at societal level, with older people in more individualistic societies reporting lower levels of loneliness (Lykes and Kemmelmeier 2014). It has been suggested that cultural values and norms affect expectations of support provided by family members. In countries with strong norms of familial responsibility, expectations of support may be higher than in countries with a more individualistic orientation. If these expectations are not fully met, then the prevalence of loneliness might be higher. It is also, however, plausible that the predictors of loneliness in older people are conditioned by cultural factors and that such factors may be linked to welfare-institutional characteristics, such as the level of generosity and coverage of pension rights or the general standard of living. Based on previous research linking welfare-institutional characteristics to health and well-being outcomes (Rothstein and Stolle 2003; Rostila 2007; Eikemo et al. 2008), we could assume that welfare-institutional characteristics may also be associated with subjective experiences of loneliness on an individual level. It is likely that welfare regimes differ in their role of preventing loneliness due to both quality and quantity of social rights and entitlements. Previous research on such cross-level associations, however, remains scant. Therefore, in this study, we explore loneliness amongst older Europeans by focusing on the absence of loneliness as well as its individual and contextual predictors.

Earlier studies and theory

Loneliness has been extensively studied and has been perceived as a problem of old age. The prevalence of loneliness in older age groups varies from study to study, sometimes depending on the way in which loneliness is measured. Dykstra’s (2009) comparative analysis suggests that about 20–30% of younger older people report serious or moderate loneliness, whereas up to 50% of the oldest old report loneliness. Importantly, the proportion of younger older people who report loneliness never or almost none of the time is in the majority. A cross-national study based on SHARE data showed that the absence of loneliness amongst people aged 65 and over ranged from 52% in Israel to 75% in Denmark (Sundström et al. 2009).

Loneliness is influenced by various individual-level factors. Usually widowhood, social isolation and solitary living are considered as key risk factors for experiencing loneliness (de Jong Gierveld 1998; Pinquart and Sörensen 2001). Further, socio-demographic risk factors include advanced old age, low educational level and low socio-economic status. The evidence regarding the influence of gender is ambiguous. Usually, women report higher levels of loneliness as compared with men, although contradictory results are reported (Beal 2006). Poor subjective health and functional limitations are limiting factors to social integration and also established risk factors for loneliness. There is also evidence that loneliness is associated with negative health outcomes, such as mental health problems, cognitive decline, poor self-rated health and increased mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015; Valtorta et al. 2016), suggesting that knowledge of factors that reduce loneliness is an important health and social policy issue.

Previous cross-national research suggests that the prevalence of loneliness in later life differs across nations (e.g. Jylhä and Jokela 1990; Sundström et al. 2009; Yang and Victor 2011; Fokkema et al. 2012; de Jong Gierveld and Tesch-Römer 2012; Lykes and Kemmelmeier 2014; Hansen and Slagsvold 2015). In Europe, the focus of our study, a north–south gradient in loneliness has been found, with Southern European countries tending to report higher levels of loneliness as compared to northern countries. Further, higher levels of loneliness have also been found in Eastern Europe as compared to West European countries (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2012; de Jong Gierveld and Tesch-Römer 2012; Hansen and Slagsvold 2015).

Based on the previous research, it is evident that the understanding of loneliness is complex, and as suggested by de Jong Gierveld and Tesch-Römer (2012), an integrative model including micro-level as well as macro-level factors should be considered in the study of loneliness. The starting point in this study is that individual-level characteristics, such as socio-economic, health and social characteristics, are relevant for people becoming lonely or not. These issues have been extensively studied during past decades (de Jong Gierveld 1998; Pinquart and Sörensen 2001). In this respect, the prevalence of loneliness could be explained using three theoretical approaches (de Jong Gierveld and Tesch-Römer 2012). First, the prevalence of loneliness could be seen as a result of unmet needs when it comes to social contacts. Second, the prevalence of loneliness could also be seen to be associated with poor living conditions, such as low socio-economic status, poor health or deprived living environment. Finally, the prevalence of loneliness could be a result of an individual’s social expectations which relates to the cognitive model of loneliness. The model, as elaborated by Perlman and Peplau (1982), suggests that loneliness is a subjective, unpleasant and distressing phenomenon resulting from a perceived discrepancy between an individual’s desired and achieved levels of social relations. According to this view, loneliness arises from the perception of a mismatch between one’s desired level and/or quality of social relationships and the actual level or quality of such relationships.

In addition, individuals’ social expectations, social integration and quality of living conditions might be conditioned by welfare-institutional arrangements. The strength of social welfare provision for the older population, through, for example, a comprehensive pension system or income maintenance programmes, decreases the risk of an older person living in poverty and hence increases the ability to be socially integrated. The welfare state might also influence loneliness by supporting services that enable older people to interact socially and to engage in social activities. Welfare states could also address the cognitive component of loneliness by addressing equality and fairness in services provided to older people. Individual social expectations, quality of living conditions and level of social integration are thus formed in the exchange with the welfare state context of a person. Due to data limitations, we focus in this study on quality of living conditions and level of social integration on the one hand and the influence of welfare state regimes on the other.

Welfare state regimes and their implications for loneliness

The welfare state regime literature continues to be closely linked to the work of Esping-Andersen (1990, 1999). Put simply, this work argues that countries can be clustered on the basis of certain commonalities in terms of their welfare-institutional configurations and the outcomes they produce (Arts and Gelissen 2002; Kumlin and Rothstein 2005). While Esping-Andersen (1990) initially operated with three regimes, the Social Democratic, the Continental and the Liberal regimes, later endeavours have included also an Eastern European and a Southern European regime (Hemerijck 2013). Based on the latter, this article operates with five European welfare state regimes: the Nordic, the Continental, the Anglo-Saxon, the Southern European and the Eastern European regimes.

The Nordic regime, including, for instance, Sweden, is characterised by a high extent of state involvement in social welfare, although an upward trend for market involvement has been observed since the 1990s (Kuisma and Nygård 2015). This regime combines individual social rights with substantial state involvement in social welfare, for example relatively generous pensions and a universal provision of defamilising public services (cf. Bambra 2007), and is characterised by relatively low levels of inequality and poverty amongst older people (Fritzell et al. 2012). This can also be expected to influence loneliness amongst older people, since universal welfare states not only tend to foster high social capital, but also facilitate social participation through an enabling welfare system (Kumlin and Rothstein 2005).

Also in the Continental regime, with Germany as an example, state involvement is substantial alongside corporate actors, the churches and non-governmental organisations. However, the focus on status-maintaining social rights (Esping-Andersen 1990), with relatively generous pensions for “insiders” and lower means-tested benefits for “outsiders” and a limited provision of public social services, is linked to higher inequality and poverty levels in old age (Schuldi 2005). Furthermore, the higher degree of familisation in these countries (Bambra 2007), in combination with a less socially enabling welfare state, would suggest that the prevalence of loneliness amongst older people is higher and conditioned by family ties.

The Anglo-Saxon regime, with the UK as an example, is characterised by a less-pronounced state involvement and a higher reliance on the market, for instance, in terms of private pensions and services. An increasing reliance upon private-funded pensions, together with rather modest and means-tested public social benefits (Clasen 2005), has led to relatively high levels of inequality and poverty amongst the older segments of the population (Fritzell et al. 2012). We can also expect a higher prevalence of loneliness amongst older persons in this regime type, due to a less socially enabling welfare state. However, the higher degree of familisation in Ireland would suggest family ties to have a more visible conditioning effect on loneliness here than in the UK.

In the Southern European regime, with Spain and Greece as examples, the family, local communities and the Catholic Church, with its principles of subsidiarity and humanitarianism, generally play a more important role for social welfare than the state. The lower provision of public social services and modest pension benefits for the majority of the older population is linked to high inequality and widespread poverty (Ferrera 1996). The high degree of familisation (Bambra 2007), in combination with a socially disenabling welfare state, would suggest the prevalence of loneliness to be highly, and perhaps exclusively, conditioned by family or other social ties.

Finally, the Eastern European regime consists of countries with very different historical and institutional legacies but with a half century of communist rule in common (Siegert 2009). Such countries are characterised by a rapid transformation from a universal social protection system (during communism) to more differentiated regimes in the post-communist era (Aidukaite 2009). While the communist era largely implied modest benefits, albeit with broad coverage, and public services for the whole population, the development after 1991 has been towards some corporatist elements, for example earnings-related pensions for some groups, mixed with liberal elements, such as means-tested benefits for older people. This means that there is considerable variation between the countries in this welfare state regime as to the way social policy functions and what its outcomes are. While some countries, such as the Czech Republic or Poland, leaned towards a corporatist model, others, such as Hungary and the Baltic countries, have been more influenced by market-based elements (Saxonberg and Szelewa 2007; Aidukaite 2009). This also makes it harder to postulate commonalities regarding the outcomes on loneliness. What may be of special interest here is the rapid transformation of society and the welfare state after the fall of communism (Siegert 2009). This may have had a curtailing effect on social participation and a triggering effect on loneliness in older people, especially in countries with a marked transformation towards liberalism, such as Hungary or Lithuania, whereas predominantly Catholic countries with a rather “continental” style of social protection, such as Poland, would suggest loneliness in older people to be a lesser problem.

Notwithstanding its centrality in comparative social policy analysis, welfare regime theory has been criticised for being simplistic, rigid, gender-biased or too static (Arts and Gelissen 2002; Baldwin 1996). As an example, the UK and Ireland are often coupled together in a “liberal” or “Anglo-Saxon” regime on the basis of the relatively high market influence on social welfare. Yet, they differ in many respects when it comes to social policy, and they do not even themselves constitute homogenous welfare regimes, with the UK covering a number of regional welfare regimes (Campbell-Barr and Coakley 2014). The same partly applies to the Nordic regime, where Finland and Iceland can be considered outliers in some respects (Kuisma and Nygård 2015), and the Continental regime, with the Netherlands sharing both “Nordic” and “Continental” welfare state features (Whelan and Maître 2008). Furthermore, the Eastern European regime ranges from “almost-Nordic” welfare states in the Baltic region, via “almost-Continental” states, to countries with a mixed welfare-institutional legacy (e.g. Hungary) (Aidukaite 2009). Despite its limitations, welfare regime theory still remains an important tool in comparative research, since it provides a fruitful way of dealing with the complexity linked to welfare-institutional configurations (Hemerijck 2013). It thus allows the researcher to make assumptions about the role that such configurations play in the lives of individuals residing in different countries. This would be the case when more suitable statistical alternatives for assessing country-level factors are absent due to, for example, limited data availability (cf. Bryan and Jenkins 2015).

The aim of this study is, hence, to assess the association between the quality of living conditions and level of social integration on the one hand and the absence of loneliness amongst older persons on the other in five European welfare regimes. While most previous studies have focused on the experience of loneliness, we follow a different course and assess the impact of the welfare state in improving well-being amongst older people, here measured as the absence of loneliness. Based on previous theoretical discussion and research, a number of hypotheses for this article are tested. First, we hypothesise that quality of living conditions and social integration are important factors for explaining the absence of loneliness on an individual level. Second, we hypothesise that the variation in the absence of loneliness is partly dependent on the type of welfare regime, but with varying degrees in different welfare regimes. We anticipate that older people in the Nordic regime, characterised as a more socially enabling welfare regime, may be less dependent on individual-level social resources for the absence of loneliness, as compared to other regimes where the absence of loneliness may to a greater extent be conditioned by family and other social ties.

Methods

The data source is the European Social Survey, ESS round 7, 2014, from which we analysed 11,389 individuals aged 60 and over from 20 countries. The main aim of the ESS is to provide high-quality data over time about behaviour patterns, attitudes and values of Europe’s diverse populations. It consists of an effective sample size of 1500 face-to-face interviews per country obtained using a random probability sample. Data are kept within and distributed by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) and are openly available at the homepage (www.europeansocialsurvey.org).

Loneliness was used as an outcome variable and was measured with the single-item question: “How much of the time during past week did you feel lonely?” The response alternatives were “none or almost none of the time”, “some of the time”, “most of the time” and “almost all of the time”. The response alternatives “some of the time”, “most of the time” and “almost all of the time” were collapsed into one category.

To assess quality of living conditions, we used three indicators from the ESS: good self-rated health, feeling of safety and household size. Self-rated health was assessed with the question: “How is your (physical and mental) health in general?” The five-graded response scale was dichotomised into “good” (“very good” and “good”) and “poor” health (“fair”, “bad” and “very bad”). Feeling of safety was captured by answers to the question: “How safe do you—or would you—feel walking alone in this area after dark?” We collapsed responses, on a scale from 1 to 4, into two categories of safety: respondents who feel unsafe and those who feel safe in the neighbourhood. For household size, we defined three categories: single-person household, two-person household and three- or more-person household.

The level of social integration was measured using marital status, frequency of being social and number of confidants. Marital status included the response alternatives: “married/partnership”, “divorced/separated”, “single” and “widowed”. In the ESS, respondents were asked: “How often do you meet socially with friends, relatives or work colleagues?” The response alternatives ranged from “never” to “every day”. We grouped the response alternatives into “less than once a month”, “once a month or more” and “once a week or more”. The number of confidants was asked with the question: “With how many people can you discuss intimate and personal matters?” The numbers were grouped into three categories: “0–1”, “2–3” and “4 and above”. We combined “0–1” into one category considering the low proportion of older people reporting no confidant, especially in countries clustered in the Nordic regime.

Socio-demographic variables included age (60–75 and 75+), gender and education. In the ESS, participants were asked to state their highest level of education achieved and included three categories: “primary” (less than lower secondary and lower secondary), “secondary” (upper secondary and post-secondary) and “tertiary” (lower and higher).

The 20 countries were divided into five different welfare regime types (Esping-Andersen 1990; Ferrera 1996; Hemerijck 2013): “Anglo-Saxon” (Ireland and UK), “Continental” (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands and Switzerland), “Eastern Europe” (Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, Lithuania and Czech Republic), “Nordic” (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) and “Southern” (Portugal and Spain).

Analyses

We used Chi-square tests to analyse variations in the absence of loneliness by welfare regimes. The association between quality of living conditions, level of social integration variables and the absence of loneliness was analysed by using multivariate logistic regression treating the welfare regime variable as a fixed effect. The results were presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We began the analyses by including quality of living conditions variables (model 1) and then added the welfare regimes as a fixed effect (model 2). A similar strategy was used for the level of social integration variables (models 3, 4). In model 5, the quality of living conditions and the level of social integration variables were analysed simultaneously, and welfare regimes were controlled for in model 6. The socio-demographic variables were controlled for in all models. The models were compared with each other using the log likelihoods.

The joint effects of welfare regimes and quality of living conditions and level of social integration variables were examined by estimating multivariate models to assess whether the association differed according to welfare regimes. Each estimate was simultaneously adjusted for all other variables. Design weights and population size weights were applied as recommended by the Weighting European Social Survey Data manual. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 21.

Results

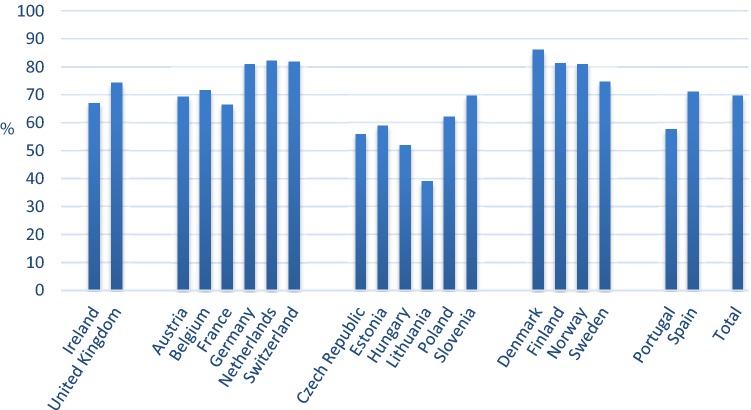

Descriptive characteristics for all included variables are reported in Table 1 according to five different welfare regimes, whereas the country prevalence of the absence of loneliness (none or almost none of the time) is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive information about socio-demographic, quality of living conditions, level of social integration and loneliness characteristics

| Anglo-Saxon (n = 1363) | Continental (n = 3468) | Eastern (n = 3234) | Nordic (n = 2272) | Southern (n = 1052) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 60–74 | 71.0 | 71.2 | 72.2 | 70.4 | 61.9 |

| 75+ | 29.0 | 28.8 | 27.8 | 29.6 | 38.1 |

| Gender | |||||

| Men | 47.9 | 50.9 | 41.1 | 50.2 | 48.7 |

| Women | 52.1 | 49.1 | 58.9 | 49.8 | 51.3 |

| Educational level | |||||

| Primary | 49.7 | 27.6 | 48.7 | 35.3 | 80.0 |

| Secondary | 15.4 | 39.7 | 35.4 | 27.3 | 6.8 |

| Tertiary | 35.0 | 32.6 | 15.9 | 37.4 | 13.2 |

| Self-rated health | |||||

| Good | 61.4 | 52.5 | 27.4 | 61.0 | 38.0 |

| Poor | 38.6 | 47.5 | 72.6 | 39.0 | 62.0 |

| Household size | |||||

| 1 | 32.0 | 24.7 | 25.5 | 30.9 | 15.7 |

| 2 | 56.7 | 66.0 | 47.3 | 64.5 | 52.1 |

| 3 and above | 11.3 | 9.3 | 27.2 | 4.5 | 32.2 |

| Feeling of safety | |||||

| Safe | 72.9 | 75.9 | 77.4 | 86.8 | 78.8 |

| Unsafe | 27.1 | 24.1 | 22.6 | 13.2 | 21.2 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/partnered | 62.5 | 70.7 | 59.0 | 61.0 | 69.6 |

| Divorced/separated | 11.8 | 9.1 | 6.5 | 15.3 | 5.1 |

| Widowed | 19.7 | 15.7 | 30.8 | 15.0 | 21.2 |

| Single (never married) | 5.9 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 8.8 | 4.1 |

| Frequency of being social | |||||

| Less than once a month | 10.0 | 7.2 | 31.7 | 4.8 | 10.6 |

| Once a month or more | 26.3 | 39.5 | 36.1 | 31.7 | 17.9 |

| Once a week or more | 63.7 | 53.3 | 32.1 | 63.5 | 71.5 |

| Number of confidants | |||||

| 0–1 | 21.7 | 15.9 | 34.4 | 17.9 | 23.0 |

| 2–3 | 39.3 | 40.1 | 38.6 | 40.9 | 38.8 |

| 4 and above | 39.0 | 44.0 | 27.0 | 41.3 | 38.3 |

| Loneliness | |||||

| None or almost none of the time | 74.0 | 76.4 | 59.3 | 79.7 | 68.5 |

| Some of the time | 19.8 | 17.8 | 22.6 | 15.9 | 19.9 |

| Most of the time | 3.3 | 3.3 | 12.4 | 2.1 | 7.5 |

| All or almost all of the time | 2.9 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 2.3 | 4.1 |

Fig. 1.

Share (%) of ESS respondents reporting the absence of loneliness

We analysed variations in loneliness according to quality of living conditions and level of social integration and separately for welfare regimes. Significant differences in loneliness were found between various groups of older people, with some exceptions (Table 2). The experience of the absence of loneliness was more common amongst those with good self-rated health in all five welfare regimes. Significant differences in loneliness between differently sized households were also found so that the absence of loneliness was common amongst older people living in two-person households as compared to three-person or larger households and single households. An exception was noticed in the Southern regime where the absence of loneliness was more common in three-person or larger households than in smaller households. A higher proportion of older people feeling safe walking outside reported the absence of loneliness in all regimes.

Table 2.

Prevalence of the absence of loneliness by welfare regimes and quality of living conditions and level of social integration variables

| Anglo-Saxon | Continental | Eastern | Nordic | Southern | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No loneliness | p | No loneliness | p | No loneliness | p | No loneliness | p | No loneliness | p | |

| Quality of living conditions | ||||||||||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||

| Good | 80.3 | ≤ 0.001 | 83.8 | ≤ 0.001 | 72.8 | ≤ 0.001 | 84.9 | ≤ 0.001 | 70.5 | 0.209 |

| Poor | 64.0 | 68.1 | 54.1 | 71.5 | 67.3 | |||||

| Household size | ||||||||||

| 1 | 53.2 | ≤ 0.001 | 48.5 | ≤ 0.001 | 26.1 | ≤ 0.001 | 59.2 | ≤ 0.001 | 32.0 | ≤ 0.001 |

| 2 | 86.2 | 85.5 | 73.6 | 89.3 | 73.7 | |||||

| 3 and above | 72.2 | 84.9 | 65.2 | 84.4 | 78.1 | |||||

| Feeling of safety | ||||||||||

| Safe | 78.0 | ≤ 0.001 | 80.5 | ≤ 0.001 | 62.3 | 0.001 | 81.3 | 0.018 | 71.5 | 0.001 |

| Unsafe | 63.6 | 64.5 | 52.4 | 69.9 | 60.8 | |||||

| Level of social integration | ||||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married/partnership | 84.4 | ≤ 0.001 | 85.8 | ≤ 0.001 | 77.5 | ≤ 0.001 | 89.3 | ≤ 0.001 | 78.1 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Divorced/separated | 58.4 | 62.1 | 36.4 | 68.2 | 52.1 | |||||

| Widowed | 52.7 | 46.1 | 32.0 | 57.5 | 44.7 | |||||

| Single | 68.2 | 62.4 | 38.3 | 71 | 58.9 | |||||

| Frequency of being social | ||||||||||

| Less than once a month | 60.2 | ≤ 0.001 | 73.1 | 0.062 | 50.4 | ≤ 0.001 | 67.6 | 0.197 | 55.4 | 0.001 |

| Once a month or more | 73.0 | 78.0 | 67.3 | 80.7 | 67.9 | |||||

| Once a week or more | 76.6 | 75.6 | 58.9 | 80.1 | 70.8 | |||||

| Number of confidants | ||||||||||

| 0–1 | 67.9 | ≤ 0.001 | 61.3 | ≤ 0.001 | 52.5 | ≤ 0.001 | 73.8 | 0.153 | 59.1 | ≤ 0.001 |

| 2–3 | 72.0 | 74.9 | 58.8 | 80.1 | 64.1 | |||||

| 4 and above | 79.0 | 83.1 | 71.1 | 82.1 | 79.8 | |||||

When it comes to the level of social integration variables, significant differences in loneliness in all welfare regimes were found regarding the marital status. The absence of loneliness was particularly common amongst married/partnered older people, whereas the absence of loneliness was less prevalent amongst widow/ers. No statistical difference between frequency of being socially connected and loneliness was found in the Continental and Nordic regimes. In the Southern and Anglo-Saxon regimes, frequent social contacts (once a week or more) had higher prevalence of the absence of loneliness, whereas in the Eastern regime, the group of older people reporting less frequent social contacts (once a month or more) had higher prevalence. A higher proportion of older people with a large number of confidants reported the absence of loneliness; however, in the Nordic regime, these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 3 shows the results from multivariate logistic regression models of the absence of loneliness amongst older people in Europe. In all models, the individual-level variables were significantly associated with the absence of loneliness. We estimated the effects of welfare regimes in models 2, 4 and 6. The results show that the odds for the absence of loneliness were significantly higher in the Anglo-Saxon, Continental and Nordic regimes compared with the Southern regime, whereas the odds were lower for the Eastern regime. However, in the final models, the estimate for the Eastern regime was no longer statistically significant. Further, the results show that the odds were greatest for the Nordic regime in the models. We compared the models using the log likelihoods. Including the welfare regimes did significantly (p < .05 based on likelihood ratio test) improve model fit, suggesting that across welfare regimes variation did exist, although individual-level features explained most of the variation.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the absence of loneliness

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Good self-rated health | 1.98*** | (1.80–2.19) | 1.79*** | (1.61–1.98) | 1.81*** | (1.64–2.01) | 1.71*** | (1.54–1.90) | ||||

| Household size | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 5.27*** | (4.72–5.07) | 5.48*** | (4.90–6.12) | 2.74*** | (2.34–3.22) | 2.91*** | (2.48–3.42) | ||||

| 3 and above | 3.70*** | (3.19–4.30) | 4.54*** | (3.88–5.31) | 2.21*** | (1.84–2.65) | 2.61*** | (2.16–3.16) | ||||

| Feeling of safety | 1.31*** | (1.17–1.46) | 1.36*** | (1.21–1.52) | 1.26*** | (1.13–1.42) | 1.3*** | (1.15–1.46) | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married/partnered | 5.53*** | (4.90–6.25) | 5.42*** | (4.79–6.12) | 2.70*** | (2.28–3.18) | 2.54*** | (2.15–2.99) | ||||

| Divorced/separated | 1.46*** | (1.23–1.73) | 1.34** | (1.13–1.60) | 1.37** | (1.15–1.63) | 1.27** | (1.06–1.52) | ||||

| Single | 1.66*** | (1.33–2.06) | 1.55*** | (1.24–1.92) | 1.50*** | (1.20–1.88) | 1.42** | (1.14–1.78) | ||||

| Frequency of being social | ||||||||||||

| Once a month or more | 1.41*** | (1.21–1.65) | 1.27*** | (1.09–1.49) | 1.34*** | (1.14–1.58) | 1.23* | (1.04–1.45) | ||||

| Once a week or more | 1.61*** | (1.38–1.86) | 1.43*** | (1.23–1.67) | 1.5*** | (1.28–1.75) | 1.37*** | (1.17–1.61) | ||||

| Number of confidants | ||||||||||||

| 2–3 | 1.44*** | (1.27–1.63) | 1.41*** | (1.24–1.59) | 1.39*** | (1.22–1.58) | 1.36*** | (1.19–1.55) | ||||

| 4 and above | 2.13*** | (1.86–2.43) | 2.07*** | (1.81–2.36) | 2.00*** | (1.75–2.30) | 1.94*** | (1.69–2.23) | ||||

| Welfare regimes | ||||||||||||

| Anglo-Saxon | 1.45*** | (1.21–1.73) | 1.35** | (1.14–1.61) | 1.44*** | (1.20–1.73) | ||||||

| Continental | 1.44*** | (1.23–1.69) | 1.28** | (1.09–1.49) | 1.40*** | (1.19–1.65) | ||||||

| Eastern | 0.75** | (0.63–0.88) | 0.82* | (0.74–1.06) | 0.94 | (0.79–1.13) | ||||||

| Nordic | 1.91*** | (1.49–2.44) | 1.80*** | (1.44–2.33) | 1.88*** | (1.47–2.42) | ||||||

| Log likelihood | 10,014.166 | 9897.519 | 10,077.75 | 10,021.45 | 9575.434 | 9522.057 | ||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.26 | ||||||

Table 4 shows the joint effect of welfare regime and quality of living conditions and level of social integration variables on loneliness. Good self-rated health was positively associated with the absence of loneliness in the Anglo-Saxon, Continental, Eastern and Nordic regimes. Living in a two-person household was associated with loneliness in all regimes; however, living in a larger household was significantly associated with the absence of loneliness in the Continental, Eastern and Southern regimes only. Feeling of safety was associated with the absence of loneliness only in the Continental regime. Of the social integration variables, to be married or partnered was associated with the absence of loneliness in all five welfare regimes. However, in the Continental regime, to be divorced or separated and to be single were also associated with the absence of loneliness as compared with the reference category of widowhood. Further, frequent social contacts were associated with the absence of loneliness in the Anglo-Saxon, Eastern and Southern regimes, whereas a large number of confidants were associated with the absence of loneliness in all but the Nordic regime.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for joint effects of welfare regime and quality of living conditions and level of social integration variables on the absence of loneliness

| Anglo-Saxon | Continental | Eastern | Nordic | Southern | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Quality of living conditions | ||||||||||

| Good self-rated health | 1.77*** | (1.39–2.26) | 2.01*** | (1.72–2.35) | 1.68*** | (1.29–2.19) | 1.65* | (1.10–2.48) | 1.07 | (0.82–1.38) |

| Household size | ||||||||||

| 2 | 2.74*** | (2.08–3.62) | 2.98*** | (2.38–3.58) | 3.41*** | (2.51–4.62) | 2.72*** | (1.77–4.19) | 3.18*** | (2.21–4.58) |

| 3 and above | 1.28 | (0.86–1.91) | 2.83*** | (2.05–3.91) | 2.59*** | (1.87–3.59) | 2.11 | (0.73–6.08) | 4.29*** | (2.89–6.38) |

| Feeling of safety | 1.22 | (0.94–1.58) | 1.48*** | (1.25–1.76) | 1.13 | (0.86–1.47) | 1.10 | (0.64–1.90) | 1.17 | (0.87–1.58) |

| Level of social integration | ||||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married/partnered | 1.86*** | (1.36–2.54) | 2.53*** | (2.01–3.20) | 3.33*** | (2.53–4.38) | 1.92* | (1.12–3.29) | 2.20*** | (1.62–3.01) |

| Divorced/separated | 0.94 | (0.64–1.37) | 1.62*** | (1.26–2.15) | 0.94 | (0.59–1.49) | 1.10 | (0.61–2.00) | 1.01 | (0.57–1.77) |

| Single | 1.40 | (0.85–1.31) | 1.71** | (1.21–2.40) | 1.02 | (0.56–1.85) | 1.15 | (0.57–2.04) | 1.08 | (0.57–2.04) |

| Frequency of being social | ||||||||||

| Once a month or more | 1.33 | (0.87–2.01) | 0.91 | (0.67–1.23) | 1.44* | (1.09–1.91) | 1.60 | (0.65–3.92) | 1.44 | (0.90–2.31) |

| Once a week or more | 1.95** | (1.32–2.87) | 0.96 | (0.71–1.29) | 1.12 | (0.85–1.49) | 1.92 | (0.81–4.53) | 2.00** | (1.34–2.98) |

| Number of confidants | ||||||||||

| 2–3 | 1.37* | (1.01–1.88) | 1.62*** | (1.32–2.00) | 1.16 | (0.90–1.51) | 1.36 | (0.78–2.35) | 1.16 | |

| 4 and above | 1.63** | (1.18–2.54) | 2.45*** | (1.97–3.04) | 1.5** | (1.11–2.02) | 1.32 | (0.76–2.93) | 2.22*** | (1.59–3.10) |

The results are based on six different specifications for each welfare regime, where we in each model with all main effects of welfare regimes have included also the joint effects of quality of living conditions and level of social integration variables. Control variables included in the estimates are gender, age, educational level, self-rated health, household size, feeling of safety, marital status, frequency of being social and number of confidants. Reference categories: self-rated health “poor”; household size “1”; feeling of safety “unsafe”; marital status “widowed”; frequency of being social “less than once a month”; number of confidants “0–1”

Significance levels: * p < 0.05; **p < 0.0; ***p < 0.001

Discussion

In this study, we explored the association between quality of living conditions and levels of social integration on the one hand and the absence of loneliness amongst older people on the other in five different types of welfare regime. Based on the findings, a number of conclusions can be drawn.

Although we analysed resources for the absence of loneliness, we confirmed a number of established findings from previous studies focusing on risk factors for loneliness (Pinquart and Sörensen 2001). We replicated that the absence of loneliness is highly related to individual characteristics, including good self-rated health, larger household size and feeling of safety, and indicators that were used as proxies for measuring the quality of living conditions. Further, our social integration indicators included marital status, frequent social contacts and larger number of confidants, and these variables were also associated with the absence of loneliness. Due to data at hand, we were not able to assess the influence of social expectations, an issue that needs to be addressed in future studies. However, we explored the integrative model of loneliness by including welfare regime typologies explaining the influence of contextual factors when it comes to the absence of loneliness.

Previous studies suggest that European cultural differences in loneliness can be attributed to differences in individualism and familialism (e.g. Lykes and Kemmelmeier 2014), and our study expands on the previous knowledge by adding a discussion on welfare regime differences in loneliness. The underlying assumption is that welfare states are important for health and well-being, for example by providing sufficient social and health care. More egalitarian and redistributive welfare regimes not only provide more income transfers, thus reducing poverty, but also provide access to social services for older people that can be expected to make a difference to well-being (Rostila 2007). Indeed, the countries clustered in the Nordic regime showed somewhat higher odds ratios, i.e. the likelihood of reporting the absence of loneliness was highest in the Nordic countries, which is also depicted in Fig. 1. Although the existing literature on loneliness differences between welfare states is clear on the better performance of the Nordic countries (e.g. Sundström et al. 2009), which could be due to more generous and universal welfare provision (Eikemo et al. 2008), and the poorer performance of the Eastern and Southern countries, it is less unanimous on the relatively good performance of the Anglo-Saxon and Continental regimes. Whether this could be seen as an outcome of changing social investment policies (Kuitto 2016), including care facilities, home help and other services aimed at enabling older people to live independently, remains unknown in our study. The Nordic welfare states have clearly the highest levels of social investments targeting older people; however, as noted by Kuitto (2016) for the period 2000–2010, the Continental and Anglo-Saxon regimes also gained ground in social investments.

An important part of our analysis surrounds how welfare regime type moderates the effect of different individual-level resources on the absence of loneliness. We argued that older people in the Nordic regime, characterised as more socially enabling, are less dependent on individual resources for the absence of loneliness. Our hypothesis was partly confirmed in our analyses, considering that frequent social contacts and number of confidants were not related to the absence of loneliness in the Nordic regime. Nonetheless, the results revealed a rather complex picture. To be married or partnered as well as to live in a two-person household was related to the absence of loneliness in all five welfare regimes, suggesting the protective effect of close or intimate relationships regardless of “individualistic” or “familialistic” country contexts (Viazzo 2010). However, living in a larger household was protective against loneliness only in the Southern, Continental and Eastern regimes, suggesting that the absence of loneliness in these regimes is to a greater extent conditioned by family ties. We know from previous research that where residential independence for older people is valued and feasible (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2012), such as in the Nordic countries, co-residence in larger households is not associated with loneliness. On the other hand, where multigenerational and larger households are the norm, co-residence is associated with lower levels of loneliness. Good self-rated health was associated with the absence of loneliness, an exception being the Southern regime. However, the outcomes of good health might be sensitive to the cut-off point on the health scale. A sensitivity analysis (not shown) was undertaken defining “fair health” as “good health”, which changed the results of the Southern regime so that fair–good health was now statistically significant, implying that the results should be treated with caution given that the health scale might be interpreted differently in different countries (Jylhä et al. 1998).

Limitations

We grouped countries into theory-based welfare regime types, instead of using country-level measures of, for example, welfare spending and income inequality. By using welfare regimes as a contextual variable, we simplified the influence of welfare-institutional factors. By using welfare regimes as our only contextual variable, we were unable to disentangle the effects of general welfare policies and economic factors from other forms of welfare-institutional characteristics, such as the provision of social services to older people. More detailed comparative analyses of, for example, social services provided to older people are necessary to reach a more comprehensive understanding of contextual influences on loneliness. Our analyses revealed that part of the explanation for individual-level variations in loneliness is dependent on the type of welfare regime. However, based on our analyses, we cannot say how much of the variation is explained by the context.

The ESS data are specifically useful in comparative cross-country research including a relatively large number of European countries. However, one limitation concerns the response rate that varies across countries, ranging from 31% in Germany to 72% in Lithuania. This might imply a selection bias. Second, it is also likely that some of the items analysed in this study were interpreted differently in different countries, such as the way loneliness or self-rated health was interpreted and responded to. Finally, as the ESS data are cross-sectional, no causal inference can be made from any association reported.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that quality of living conditions and level of social integration are important for explaining the absence of loneliness. However, the influence of these factors is conditioned by the type of welfare regime. The Nordic as well as the Anglo-Saxon and Continental regimes perform better than the Southern and Eastern regimes when it comes to preventing older people from experiencing loneliness. State involvement in social welfare in the Nordic regime seems to promote especially social integration that makes older people less dependent on social resources for their loneliness experiences.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments.

Footnotes

Responsible editor: Marja J. Aartsen.

References

- Aidukaite J. Old welfare state theories and new welfare regimes in Eastern Europe: challenges and implications. Communist Post Communist Stud. 2009;42:2–39. doi: 10.1016/j.postcomstud.2009.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arts W, Gelissen J. Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. J Eur Soc Policy. 2002;12:137–158. doi: 10.1177/0952872002012002114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin P. Can we define a European welfare state model? In: Greve B, editor. Comparative welfare systems. London: Macmillan; 1996. pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bambra C. Defamilisation and welfare state regimes: a cluster analysis. Int J Soc Welf. 2007;16:326–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beal C. Loneliness in older women: a review of the literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27:795–813. doi: 10.1080/01612840600781196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan ML, Jenkins SP. Multilevel modelling of country effects: a cautionary tale. Eur Sociol Rev. 2015;32:3–22. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcv059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Barr V, Coakley A. Providing choice? A comparison of UK and Ireland’s family support in a time of austerity. J Int Comput Soc Policy. 2014;30:231–244. doi: 10.1080/21699763.2014.951381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clasen J. Reforming European welfare states. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J. A review of loneliness: concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Rev Clin Gerontol. 1998;8:73–80. doi: 10.1017/S0959259898008090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J, Tesch-Römer C. Loneliness in old age in Eastern and Western European societies: theoretical perspectives. Eur J Ageing. 2012;9:285–295. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0248-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J, Dykstra PA, Schenk N. Living arrangements, intergenerational support types and older adult loneliness in Eastern and Western Europe. Demogr Res. 2012;27:167–200. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA. Older adult loneliness: myths and realities. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6:91–100. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikemo TA, Bambra C, Judge K, Ringdal K. Welfare state regimes and differences in self-perceived health in Europe: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:2281–2295. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. Social foundations of postindustrial economies. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera M. The ‘southern’ model of welfare in social Europe. J Eur Soc Policy. 1996;6:17–37. doi: 10.1177/095892879600600102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema T, de Jong Gierveld J, Dykstra PA. Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. J Psychol. 2012;146:201–228. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.631612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzell J, Bäckman O, Ritakallio V-M. Income inequality and poverty: do the Nordic countries still constitute a family of their own? In: Kvist J, Fritzell J, Hvinden B, Kangas O, editors. Changing social equality. Bristol: Policy Press; 2012. pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T, Slagsvold B. Late-life loneliness in 11 European countries: results from the generations and gender survey. Soc Indic Res. 2015;124:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0769-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerijck A. Changing welfare states. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M, Jokela J. Individual experiences as cultural: a cross-cultural study on loneliness among the elderly. Ageing Soc. 1990;10:295–315. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X00008308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Jokela J, Heikkinen E. Is self-rated health comparable across cultures and genders? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(3):144–152. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53B.3.S144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuisma M, Nygård M. The European Union and the Nordic models of welfare—path dependency or policy harmonisation? In: Grøn CH, Nedergaard P, Wivel A, editors. The Nordic countries and the European Union. Still the other European community? The Nordic Countries and the European Union. London: Routledge; 2015. pp. 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kuitto K. From social security to social investment? Compensating and social investment welfare policies in a life-course perspective. J Eur Soc Policy. 2016;26:442–459. doi: 10.1177/0958928716664297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumlin S, Rothstein B. Making and breaking social capital. Comp Polit Stud. 2005;38:339–365. doi: 10.1177/0010414004273203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lykes VA, Kemmelmeier M. What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2014;45:468–490. doi: 10.1177/0022022113509881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman D, Peplau LA. Theoretical approaches to loneliness. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: Wiley; 1982. pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: a meta-analysis. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2001;23:245–266. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rostila M. Social capital and health in European welfare regimes: a multilevel approach. J Eur Soc Policy. 2007;17:223–239. doi: 10.1177/0958928707078366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein B, Stolle D. Social capital, impartiality and the welfare state: an institutional approach. In: Hooghe M, Stolle D, editors. Generating social capital. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2003. pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Saxonberg S, Szelewa D. The continuing legacy of the communist legacy? The development of family policies in Poland and the Czech Republic. Soc Polit. 2007;14:351–379. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxm014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldi M. The reform of Bismarckian pension systems: a comparison of pension politics in Austria, France, Germany, Italy and Sweden. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Siegert D. Why no ‘Dilemma of Simultaneousness’? The ‘great transformation’ in Eastern Central Europe considered from the point of view of post-socialist research. In: Frank R, Burghart S, editors. Driving forces of socialist transformation. Wien: Praesens; 2009. pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sundström G, Fransson E, Malmberg B, Davey A. Loneliness among older Europeans. Eur J Aging. 2009;6:267–275. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102:1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viazzo PP. Family, kinship and welfare provision in Europe, past and present: commonalities and divergences. Contin Change. 2010;25(1):137–159. doi: 10.1017/S0268416010000020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan CT, Maître B. Poverty, deprivation and economic vulnerability in the enlarged EU. In: Alber J, Fahey T, Saraceno C, editors. Handbook of quality of life in the enlarged European Union. London: Routledge; 2008. pp. 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Victor C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc. 2011;31(8):1368–1388. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1000139X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]