Abstract

Although the importance of sexuality and physical intimacy for well-being of older adults has been recognized, the role of sexuality in successful aging (SA) has been largely neglected. Building on our previous work, here we further validated a three-dimensional model of SA and examined its associations with sexual satisfaction and change in sexual interest among older heterosexual couples (aged 60–75 years). Participants were recruited in a probability-based survey, which was carried out in 2016–2017 in four European countries. Using structural equation modeling of the Actor–Partner Interdependence, we observed significant relationships between SA and sexual satisfaction for both male and female partners across countries. Among women, their retrospectively assessed change in sexual interest over the past 10 years was consistently associated with sexual satisfaction. Partner effects were gender-specific: male partners’ SA was significantly related to their female partners’ change in sexual interest, which in turn was linked to male partners’ sexual satisfaction. The findings point to substantial ties between successful aging and sexuality in older European couples. Taking into account the prevalent stereotypes about old age and sexuality, this study’s findings can assist professionals working with aging couples.

Keywords: Successful aging, Sexual satisfaction, Sexual interest, Older couples

Introduction

Research consistently demonstrates that the majority of older adults are sexually active, and that sexual activity and intimacy play an important role for their quality of life (Lindau and Gavrilova 2010; Lee et al. 2016a, b). The evidence base in this area is growing, and recent research has identified a relationship between positive psychological well-being and sexual activity in older adulthood (Fileborn et al. 2015; Kleinstäuber 2017). Surveys have also found that regular sexual activity is associated with less relationship strain (Orr et al. 2017) and that the frequency and importance of sexual activity are positively correlated with quality of life for older adults who are single or in a relationship (Laumann et al. 2006; Flynn and Gow 2015).

The role of sexual activity and intimacy for the health and well-being of older adults has also been recognized and promoted by governments and organizations that support people in older age (cf. Marshall 2010). Thus, sexuality would seem to play a role in successful aging (SA), as one of the components that distinguish between positive and negative or problematic aging process. This conceptualization, however, remains hampered by a lack of empirical research on the relationship between sexual activity and SA. In an earlier paper (Štulhofer et al. 2018), we proposed a model of SA using cross-cultural data from four European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Norway and Portugal). This paper builds on that work and further examines the SA model and its association with sexual satisfaction in a sample of older heterosexual couples recruited from the aforementioned European countries.

Successful aging: toward a less biomedical and more psychosocial model

Although SA—a concept that has been around for over three decades—continues to gain prominence in the gerontology field, there is no single agreed definition of it (Martinson and Berridge 2015). However, most definitions include physical, psychological, and social dimensions. For example, Carver and Buchanan (2016) described SA in terms of these three factors and emphasized the social dimension as involving engagement or connectedness with others. The influence of early conceptualizations of the concept can still be seen, as predominant contemporary understandings of SA are often built upon the model proposed by Rowe and Kahn (1997), which comprised three main components: (1) low risk of disease and disability, (2) high cognitive and physical function, and (3) active engagement with life. Rowe and Kahn’s impetus to develop a model of aging which would counteract the predominant view within gerontology at that time, of older age characterized predominantly by disease and disability, has been highly influential (Martin et al. 2015).

More recently, due to the findings that many older individuals age successfully in spite of some health problems or decline in their physical ability (see for example, Pruchno and Carr 2017), the Rowe and Kahn model has been criticized for placing too much emphasis on current physicality, while neglecting the influence of life-course factors (Stowe and Cooney 2015). Consequently, a number of researchers replaced the health facet of the three-dimensional SA model with life satisfaction facet, which is the approach also followed in the current study.

It is interesting that while the SA concept attempts to capture the totality of the aging experience, sexual aspects of aging have not been systematically linked to the concept (for preliminary explorations see Woloski-Wruble et al. 2010; Thompson et al. 2011). This is despite sexual activity and satisfaction having been recognized for their benefits to psychological well-being and physical health in older individuals (DeLamater 2012; Træen et al. 2017a). Recently, our research group published the first systematic exploration of links between SA and changes in sexual interest and enjoyment among older individuals from four European countries (Štulhofer et al. 2018), but a new measure of SA proposed in the paper needs further validation in dyadic context.

Sexual interest, sexual satisfaction and well-being in older couples

In addition to a paucity of research linking SA and sexuality, there seems to be no research that employed dyadic analysis to examine this association—in spite of the findings pointing to the role of relationship status and quality (Waite et al. 2015). Lee et al. (2016b) analyzed data from the English Longitudinal Study on Ageing (ELSA) that included 4296 participants who were currently married, in a civil partnership, or cohabiting. Participants who reported higher sexual desire, fewer sexual function problems, and more regular partnered sexual activity, had more positive scores on sexual well-being measures. This has been supported by a smaller study, where older adults who engaged in frequent sexual intercourse were more likely to report a higher quality of intimate relationship (Flynn and Gow 2015). In the few studies that did collect dyadic data (i.e., constructs of interest were assessed in both partners), frequent sexual activity was also found positively associated with relationship quality. Orr et al. (2017) examined data from 1942 couples who were married to each other or cohabiting from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) and found, using dyadic analysis, that more frequent sexual activity was associated with less relationship strain. In addition, the authors reported that a mismatched level of importance placed on sex was associated with more relationship strain.

Interesting gender differences have been found in another study that explored older couples’ sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness across five countries (Heiman et al. 2011). In their analysis, which was carried out by gender (no dyadic analysis was attempted), the authors found that “women reported significantly more sexual satisfaction than men and men more relationship happiness than women.” Physical intimacy, such as kissing, cuddling and caressing which, predicted relationship happiness among men, as well as sexual satisfaction in both male and female partners. Sexual frequency was related to sexual satisfaction for both women and men, but not relationship happiness.

Qualitative research, although also rare in this area, adds to these findings. An early study (Hinchliff and Gott 2004) explored the importance and meaning of sexual relationships for 28 participants, aged 50–86 years, who had been married for a minimum of 20 years (the average length of marriage was 43 years). Although not dyadic, this study found overwhelming agreement that sexual activity and intimacy had benefits for the marriage because these acts—which were understood as an expression of love—enhanced the communication of emotion and helped to maintain a sense of trust and security within the relationship.

In spite of research findings which point to a decline in sexual interest in aging men and women (DeLamater 2012; Træen et al. 2017a), there is evidence that sexual satisfaction does not necessarily follow the same trajectory (Træen et al. 2017b). Research has shown that older men and women’s sexual satisfaction may remain relatively high regardless of changes in sexual activity (frequency and type) and a decrease in motivation for sex (Hinchliff and Gott 2004). Indeed, older adults report high relationships satisfaction despite sexual inactivity (Hinchliff et al. 2018). To the best of our knowledge, the current study represents the first attempt at dyadic analysis of SA and sexual satisfaction. Its importance is reflected in the increasing number of people across the developed world who are living in old age, with their sexual rights often neglected or unrecognized (Barrett and Hinchliff 2017).

Considering that the concept of SA has only fragmentarily been related to older individuals’ sexuality (we were unable to find any dyadic study on sexual aging and sexual satisfaction among older partners), reflecting an ongoing separation between the fields of gerontology and sexuality research, this study had two aims. The first was to validate a three-dimensional measure of SA that was recently developed using individual data (Štulhofer et al. 2018) in this four-country dyadic sample. The validation was a precondition for exploring direct and indirect associations between SA and sexual satisfaction, which was our second aim. Based on the literature on decreasing sexual interest in older age (Lee et al. 2016a; Graham et al. 2017) and its controversial role in aging men’s and women’s well-being (Lee et al. 2016b), a mediation model of the association between SA and sexual satisfaction was proposed, with changes in sexual interest hypothesized to mediate the relationship.

Method

Participants and procedures

Data for this study were collected in a survey on sexuality in older men and women that was carried out during 2016 in four European countries (Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Portugal). Using probability-based sampling, the survey recruited 3816 men and women aged 60–75 years. National phone registry was used as sampling frame in all countries but Portugal, where multi-stage cluster-based sampling—the standard approach for local public opinion surveys—was employed. During recruitment, prospective participants were instructed that current sexual (in)activity was irrelevant for participation. Response rates were 68% in Norway, 52% in Denmark, 57% in Belgium and 26% in Portugal. As part of the study, a subsample of couples was recruited in each country (218 in Norway, 207 in Denmark, 135 in Belgium, and in 117 Portugal). This dyadic dataset is used in the current study. The recruitment for the dyadic sample was a part of the general sampling procedure and included the same inclusion criteria (specific age and language proficiency).

Table 1 summarizes sociodemographic characteristics of the dyadic samples. The average age was the highest in Denmark (M = 67.7, SD = 3.87) and the lowest in Portugal (M = 65.6, SD = 4.18). Accordingly, reported duration of the relationship/marriage was the longest in Danish couples (M = 40.58, SD = 12.77) and the shortest in Portuguese couples (M = 30.30, SD = 17.42). There were also marked between-country differences in religiosity (Portuguese couples reported the highest and Norwegian couples the lowest frequency of attending religious services) and education levels. Norwegian couples were characterized by the highest proportion of college-educated couples and the lowest proportion of only primary school-educated partners (9.9%), while the reverse was true for Portuguese couples.

Table 1.

Basic sociodemographic characteristics of the dyadic sample (by Country)

| Norway | Denmark | Belgium | Portugal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male partner | Female partner | Male partner | Female partner | Male partner | Female partner | Male partner | Female partner | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 60–65 | 57 (26.1) | 93 (42.7) | 59 (28.5) | 78 (37.7) | 38 (28.1) | 66 (48.9) | 50 (42.7) | 72 (61.5) |

| 66–70 | 85 (39.0) | 86 (39.4) | 73 (35.3) | 90 (43.5) | 60 (44.4) | 48 (35.6) | 42 (35.9) | 35 (29.9) |

| 71–75 | 76 (34.9) | 39 (17.9) | 75 (36.2) | 39 (18.8) | 37 (27.4) | 21 (15.6) | 25 (21.4) | 10 (8.5) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary education | 26 (11.9) | 27 (12.4) | 59 (28.9) | 50 (24.3) | 17 (15.6) | 25 (18.6) | 38 (32.5) | 50 (42.7) |

| Secondary education | 65 (29.8) | 86 (39.4) | 72 (34.3) | 79 (38.4) | 72 (50.3) | 71 (52.9) | 62 (53.0) | 47 (50.2) |

| Tertiary education | 127 (58.2) | 104 (47.7) | 73 (35.8) | 77 (37.4) | 46 (34.1) | 38 (28.4) | 17 (14.5) | 20 (17.1) |

| Current relationship duration | ||||||||

| Up to 10 years | 13 (6.0) | 13 (6.3) | 13 (9.6) | 23 (19.7) | ||||

| 11–20 years | 14 (6.4) | 5 (2.4) | 3 (2.2) | 4 (3.4) | ||||

| 21–30 years | 17 (7.8) | 12 (5.8) | 6 (4.4) | 9 (7.7) | ||||

| 31–40 years | 34 (15.6) | 33 (15.9) | 24 (17.8) | 29 (24.8) | ||||

| 41 or more years | 119 (54.6) | 136 (65.7) | 82 (60.7) | 39 (33.3) | ||||

| Religiosity | ||||||||

| Never | 78 (35.8) | 66 (30.3) | 65 (31.4) | 52 (25.1) | 50 (37.0) | 51 (37.8) | 29 (24.8) | 23 (19.7) |

| Less than once a year | 50 (22.9) | 47 (21.6) | 50 (24.2) | 54 (26.1) | 21 (15.6) | 11 (8.1) | 18 (15.4) | 14 (12.0) |

| Once a year | 32 (14.7) | 24 (11.0) | 30 (14.5) | 33 (15.9) | 10 (7.4) | 12 (8.9) | 15 (12.8) | 5 (4.3) |

| Twice a year | 30 (13.8) | 47 (21.6) | 35 (16.9) | 34 (16.4) | 23 (17.0) | 29 (21.5) | 17 (14.5) | 17 (14.5) |

| Once a month | 9 (4.1) | 11 (5.0) | 13 (6.3) | 20 (9.7) | 14 (10.4) | 16 (11.9) | 12 (10.3) | 13 (11.1) |

| Once every 2 weeks | 7 (3.2) | 10 (4.6) | 6 (2.9) | 7 (3.4) | 8 (5.9) | 5 (3.7) | 7 (6.0) | 15 (12.8) |

| Once a week or more | 11 (5.0) | 10 (4.6) | 5 (2.4) | 5 (2.4) | 9 (6.7) | 7 (5.2) | 16 (13.7) | 27 (23.1) |

| Place of residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 69 (31.7) | 81 (39.1) | 30 (22.2) | 11 (9.4) | ||||

| Small town | 81 (37.2) | 67 (32.4) | 70 (51.9) | 30 (25.6) | ||||

| Medium-sized city | 24 (11.0) | 28 (13.5) | 18 (13.3) | 22 (18.8) | ||||

| Suburb of a large city | 19 (8.7) | 20 (9.7) | 8 (5.9) | 17 (14.5) | ||||

| Central large city | 25 (11.5) | 9 (4.3) | 4 (3.0) | 34 (29.1) | ||||

The fieldwork was carried out by an international polling company. After initially being contacted by phone, prospective participants were sent a postal questionnaire (developed in English and translated into local languages by members of an international research team) that included slightly over 200 items. Sampled couples were instructed to complete the questionnaire separately. Participant recruitment and data collection procedures strictly followed ethical standards adopted by ESOMAR and the guidelines for ethical research of the Norwegian Association of Marketing and Opinion Research.

Measures

Successful aging (SA) was operationalized as a latent construct composed of three dimensions: (1) mental health, (2) social (dis)connectedness, and (3) life satisfaction. Mental health facet was indicated by a brief and psychometrically validated depression scale, the Symptom Checklist Depression (SCL-DEP; Søgaard and Bech 2009). The six-item scale had acceptable reliability in this study (country-specific Cronbach’s α was in the .79–.83 range). Scores were reverse-recoded, so higher scores indicate low or no depression. For confirmatory factor analysis, the six items were randomly assigned to three parcels. As a proxy for social disconnectedness, we used a loneliness scale developed by Cacioppo et al. (2015). The three-item scale (e.g., “How often do you feel isolated from others?”) had satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s α = .77 to .81). The scores were reverse-recoded, with higher scores denoting low or no loneliness. Finally, life satisfaction was measured by a four-item (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life” and “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal”) version of the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985). Responses were recorded on a seven-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores representing higher levels of life satisfaction. The scale had excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α was .90 in all four countries).

Sexual satisfaction was measured using two strongly related items (r = .68–.80): “Thinking about your sex life in the last year, how satisfied are you with your sexual life?” and “How satisfied are you with the current level of sexual activity in your life, in a general way?” Answers to these questions were anchored using a five-point scale. Responses to the second item were reverse-coded, so that higher summed scores point to higher satisfaction. The composite indicator had satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s α = .77–.81).

The following question was used to operationalize a change in sexual interest among older couples: “Compared to 10 years ago, how would you rate your interest in sex?” Answers were recorded on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = much lower to 5 = much higher. The mid-point on the scale (3) denoted no change in sexual interest over the past decade.

Statistical analysis

Developed originally for studying couples, dyadic analysis has several advantages over the standard (individualized) approach (Muise et al. 2018). In brief, dyadic approach takes into account the reality of a couple’s shared experiences—the interdependency of the partners’ daily practices, ranging from their sexual activity to the dynamics of aging together. Dyadic analysis also enables disentangling actor (i.e., the partner in focus) from his/her partner effects, which can be particularly useful when partners’ roles are potentially specific—for example, due to gendered social norms and expectations. This study’s approach to dyadic data is based on the Actor–Partner Independence Model (APIM; Kenny et al. 2006). In essence, APIM enables simultaneous estimation of direct and indirect associations for each coupled individual by taking into account non-independence of their responses. Although the problem with non-independent observation (and underestimated standard errors) can be remedied by various statistical techniques, here we used structural equation modeling approach. In all subsequent analyses, the term actor indicates the person who’s behavior or evaluation are investigated, while the term alter refers to his or her partner.

First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed using dyadic data to re-assess the three-dimensional model of SA that was developed using individual participants’ data (Štulhofer et al. 2018). The following cutoff values were considered to indicate adequate model fit: Tucker–Lewis incremental fit index ≥ .95 (excellent fit) or ≥ .90 (acceptable fit), and the RMSEA (root-mean-square error of approximation) index of parsimony ≤ .05 (excellent fit) or ≤ .08 (acceptable fit). Next, we tested the model’s invariance across country by comparing fit of the baseline (unconstrained) multi-group model with progressively more constrained models representing metric and scalar invariance (van de Schoot et al. 2012). Due to the sample size, CFI difference test (∆CFI) was applied instead of the standard ∆Chi-square test. Values ≤ .01 indicated equally fitting models (Cheung and Rensvold 2002). For cross-cultural comparisons to be justified, at least partial scalar invariance was required (Byrne et al. 1989). Finally, the hypothesized mediation was tested by bootstrapping indirect effects using 1000 re-samples (Shrout and Bolger 2002). Full information maximum likelihood approach was used to deal with missing information (Graham 2012).

All analyses were carried out in IBM AMOS 22 statistical software package (Arbuckle 2013).

Results

Overall, couples reported a negative change in sexual interest (M = 2.19, SD = .86), which indicated that the current level of sexual interest was, for most participants, “somewhat lower” than they perceived it to have been 10 years ago. Paired-samples t test results pointed to a significantly and substantially smaller reduction in male compared to female partners’ sexual interest (t(665) = 4.66, p < .001). The difference, however, was significant only in Denmark and Belgium. At the couple level, mean change in sexual interest was the least negative in Denmark (M = 2.30, SD = .63) and the most negative in Belgium (M = 1.93, SD = .72). Sexual satisfaction was significantly higher among female than male participants (t(600) = − 2.36, p < .05). As in the case of change in sexual interest, levels of sexual satisfaction were the highest among Danish (M = 3.59, SD = .82) and the lowest in Belgian couples (M = 3.31, SD = .91).

Across countries, correlations between the change in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction levels were highly significant (p < .001) and positive (r = .30–.50), reflecting moderate to strong correspondence between sexual satisfaction and a lower decrease in sexual interest. In the pooled sample, neither partners’ age nor their age differential (i.e., age difference between partners/spouses) was significantly associated with the reported change in sexual interest or satisfaction.

Couples’ successful aging model

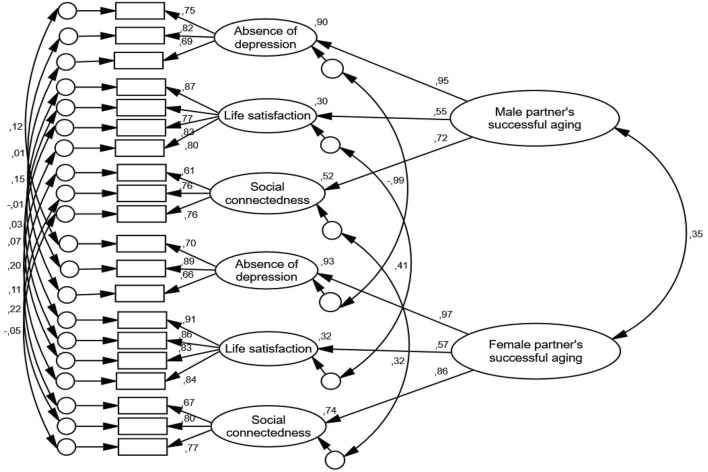

Figure 1 shows the APIM version of the three-dimensional model of SA that was developed and validated in our earlier study. Given that the initial testing resulted in an adequate fit to data: χ2(150) = 470.96, CFI = .955, RMSEA = .056 (90% CI .051–.062), there was no need for model re-specification. Next, the model was explored in a multi-group perspective, with countries as groups, to assess its cross-cultural invariance. This extensive analysis resulted with only configural invariance confirmed (i.e., loadings of the first and second factor level were invariant across country). Compared to the baseline or unconstrained model (χ2(600) = 1193.31, CFI = .918, RMSEA = .038 [90% CI .035–.042]), the configurally invariant model fitted the data equally well (χ2(618) = 1243.13, CFI = .914, ∆CFI = .004, RMSEA = .039 [90% CI .036–.042]). These findings suggested conceptual, but not metric cross-cultural validity of the SA model. Thus, direct comparisons of the full path analytic model among countries were methodologically unwarranted.

Fig. 1.

Confirmatory factor analytic model of successful aging (actor-partner interdependence model). Values next to double-arrow paths represent correlations, those above one-headed arrows represent standardized path coefficients, while values next to latent variables of the first order represent coefficients of determination (R2)

Associations between successful aging, sexual interest and sexual satisfaction by country

Full path analytic multi-group model had acceptable fit to data (χ2(888) = 1579.1, CFI = .912, RMSEA = .034 [90% CI .031–.037]). After a nonsignificant path between female partner’s SA and male partner’s change in sexual interest was omitted, fit of the final structural equations APIM remained unchanged (χ2(892) = 1581.5, CFI = .912, RMSEA = .034 [90% CI .031–.037]).

Predictably, associations between the partners’ SA (rNorway = .37, p < .001, rDenmark = .25, p < .01, rBelgium = .32, p < .01, rPortugal = .34, p < .001), as well as between their levels of sexual satisfaction (rNorway = .48, p < .001, rDenmark = 35, p < .001, rBelgium = .44, p < .001, rPortugal = .51, p < .001), were all highly significant and mostly of moderate size. In regard to other structural associations among the constructs of interest, which are shown in Table 2, three patterns emerged. Firstly, we consistently observed a significant and positive relationship between SA and sexual satisfaction in both female (except for Belgian women) and male partners. The effects were small to moderate, with somewhat higher values for men. Secondly, among women in all four samples, but only among Norwegian and Belgian men, changes in sexual interest were significantly associated with sexual satisfaction. The relationship was moderately sized in women and small in men, with a more positive (or less negative) change in sexual interest corresponding to a higher sexual satisfaction. Thirdly, cross-partner effects were gender-specific. Male partner’s SA was significantly related to their female partner’s change in sexual interest in Norway and Denmark. That is, the higher the men’s SA score, the less negative the change in his partner’s sexual interest. Women’s change in sexual interest was significantly associated with their partner’s sexual satisfaction (the less negative the change she reported, the higher his sexual satisfaction)—except in the Belgian sample. We observed no significant direct associations between actor’s SA and partner’s sexual satisfaction.

Table 2.

Associations among successful aging, sexual interest and sexual satisfaction in couples from four European countries (path analytic APIM)

| Norway | Denmark | Belgium | Portugal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (S.E.) | Ba (S.E.) | Ba (S.E.) | Ba (S.E.) | |

| Male partner paths | ||||

| Successful aging to sexual satisfaction | .32*** (.08) | .27** (.09) | .28* (.11) | .56*** (.11) |

| Successful aging to change in sexual interest | .11 (.06) | .10 (.05) | − .13 (.09) | .22** (.09) |

| Change in sexual interest to sexual satisfaction | .26** (.09) | .08 (.09) | .27** (.10) | .18 (.11) |

| Actor’s successful aging to partner’s sexual satisfaction | .12 (.07) | − .01 (.08) | .19 (.11) | .06 (.09) |

| Actor’s successful aging to partner’s change in sexual interest | .24** (.08) | .16* (.07) | .06 (.10) | .06 (.10) |

| Actor’s change in sexual interest to partner’s sexual satisfaction | .10 (.08) | .22* (.09) | .13 (.10) | − .03 (.10) |

| Indirect effect 95% CI | Indirect effects 95% CI | Indirect effect 95% CI | Indirect effect 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation | ||||

| Successful aging to sexual satisfaction through actor’s change in sexual interest | .05–.20** | .01–.11* | − .13 to .05 | − .13 to .11 |

| Successful aging to sexual satisfaction through partner’s change in sexual interest | .03–.16** | .02–.17** | − .09–.06 | − .19 to .07 |

| Norway | Denmark | Belgium | Portugal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (S.E.) | Ba (S.E.) | Ba (S.E.) | Ba (S.E.) | |

| Female partner paths | ||||

| Successful aging to sexual satisfaction | .29*** (.07) | .17* (.07) | .15 (.10) | .24** (.08) |

| Successful aging to change in sexual interest | .02 (.07) | .09 (.06) | .06 (.10) | .12 (.09) |

| Change in sexual interest to sexual satisfaction | .33*** (.07) | .36*** (.08) | .22** (.08) | .58*** (.09) |

| Actor’s successful aging to partner’s sexual satisfaction | − .06 (.08) | .10 (.07) | .07 (.10) | − .12 (.09) |

| Actor’s change in sexual interest to partner’s sexual satisfaction | .38*** (.07) | .23** (.09) | .16 (.09) | .38*** (.10) |

| Indirect effect 95% CI | Indirect effects 95% CI | Indirect effect 95% CI | Indirect effect 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation | ||||

| Successful aging to sexual satisfaction through actor’s change in sexual interest | − .06 to .08 | − .01 to .08 | − .03 to .07 | − .05 to .19 |

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

aUnstandardized path coefficients

Finally, we explored the hypothesized mediating role of change in sexual interest in the relationship between participants’ SA and sexual satisfaction. Indirect effects were significant only among men in the two Scandinavian countries, pointing to that constructs other than the dynamics of sexual interest underlie this association in most cases and especially among women. Importantly, the association between SA and sexual satisfaction in Norwegian and Danish men was mediated not only by their own but also their partner’s change in sexual interest.

To assess the robustness of the reported findings, all four country-specific models were carried out with relationship duration controlled for (the construct was related to all six variables in the structural part of the model). According to the standard Chi-square difference test, this more complex model failed to significantly improve model fit across countries.

Discussion

To assist in filling the gap in understanding the linkage between SA and sexual aging, this study used a cross-cultural probability-based sample of aging couples from four European countries to explore direct and indirect associations among SA, sexual satisfaction and changes in sexual interest. Significant and systematic relationships between SA and sexual satisfaction emerged as the central finding.

Our findings support the validity of the new measure of SA that includes indicators of life satisfaction, a proxy for social connectedness, and a proxy for mental and emotional functioning. It should be noted that the model was not invariant across the four countries, suggesting the role of specific sociocultural influences on older couples’ SA. This is supported by structural differences that exist between the countries. In addition to socioeconomic differences (Norway has a notably higher GDP per capita than Denmark and Belgium, and all three countries have substantially higher GDP than Portugal), there are sociocultural differences—particularly in terms of gender equality. According to a global gender gap measurement, Norway was ranked the second most egalitarian country, Denmark 19th, Belgium 24th and Portugal 31st (World Economic Forum 2017).

In the structural model in which changes in sexual interest over the past 10 years were conceptualized to mediate the association between SA and sexual satisfaction, we found consistent and moderate direct relationship between each partner’s SA and sexual satisfaction levels (Belgian women were the sole exception), confirming the role of sexuality in older couples’ aging well. The associations were somewhat higher in the case of men, which seems to corroborate the repeatedly reported observation that older men rate sex as substantially more important than older women (Foley 2015; Træen et al. 2018). Interestingly, associations between the retrospectively assessed change in sexual interest in the past 10 years and sexual satisfaction were consistently significant (and higher) in women but not men. The finding may reflect the observation that women experienced a more substantial negative change in sexual interest over the past 10 years than their partners, which is consistent with the available literature on decreasing sexual motivation in older individuals (Lindau et al. 2007; Laumann et al. 2008) and a higher prevalence of sexual desire problems in women, compared to men (Grant et al. 2007; Mitchell et al. 2013). Among men, the relationship between change in sexual interest and satisfaction reached significance only in Norway, the country characterized by nonsignificant gender differential in the reduction of sexual interest, and Belgium—the country with the highest reduction in sexual interest. The finding that the mediating role of sexual interest—either personal or partner’s—was observed only among Norwegian and Danish men cannot be interpreted based on the collected data. In speculating about possible reasons, two come to mind. Taking into account that men in the two Scandinavian samples were older than Belgian and Portuguese men, the observation may reflect an increasing tendency in aging men to use the dynamics of their sexual interest as a proxy for sexual vitality. In regards to the mediating role of the female partner’s sexual interest, substantially higher levels of gender equality in the Scandinavian countries, compared to the rest of Europe, may provide an answer. The possibility that societal levels of gender equality are related to cross-partner sexual dynamic in older couples should be empirically probed in the future.

Our study findings indicate that the link between sexuality and SA in older European couples is gender-specific. While men’s SA was important for their female partners’ sexual interest (but not the other way around), women’s sexual interest significantly contributed to their male partners’ sexual satisfaction. The direction of these associations remains, however, unclear. For example, the male partner’s aging well may have contributed to a lower reduction in his female partner’s sexual interest, but the opposite is also possible—as well as a bi-directional relationship between SA and change in sexual interest. The observed gender differences are not surprising given the traditional dynamics of sexual interaction in heterosexual couples, in which partners’ roles are highly gendered (initiating men and responsive women) by cultural norms and social expectations (Crawford and Popp 2003; Træen and Hovland 1998). These normative factors are likely to have played a particularly prominent role in the socialization of older age cohorts. However, as suggested by recent dyadic studies (Muise et al. 2014; Dewitte and Mayer 2018), some of these sexuality-related gender differences may not be confined to older couples. Apart from the sociocultural influences, the potential disruptiveness of the male partner’s less successful aging for the couple’s sexual life may also reflect physical (problematic male sexual function) and psychological issues (giving up sex due to a declining sense of masculinity; see Jowett et al. 2012).

Finally, the fact that we observed no direct cross-partner associations between SA and sexual satisfaction suggests—apart from pointing to the relevance of older individuals’ sexual agency—that a person’s SA is likely a necessary but not sufficient condition for his or her partner’s sexual satisfaction. Related to this issue, changes in sexual interest might not be among the most relevant mechanisms that underlie the association between SA and sexual satisfaction. Future studies should explore other activities and sensations, such as erotic touching and cuddling (see Heiman et al. 2011), as potential mediators. Taking into account that changes in sexual interest reported by female partners’ played little or no part in their sexual satisfaction, relationship quality and emotional intimacy may be additional mechanisms to consider (Dewitte and Mayer 2018).

Overall, our findings corroborate a systematic association between SA and sexuality, emphasizing the role of sexual satisfaction for older couples’ quality of life. Taking into account the moderate strength of observed associations between SA and sexual satisfaction, which reflect the fact that some older couples are not sexually active and some not even interested in sex (Træen et al. 2017a, b), sexual satisfaction should be conceptualized as a predictor or contributor to SA, but not one of its facets. The absence of a systematic relationship between SA and (decreasing) sexual interest in the sampled couples suggests that potential difficulties in accepting age-related changes in one’s sexual motivation do not affect the individual’s SA. However, we found some evidence among female participants that this may not be the case if it is their male partner’s sexual interest that has declined.

Study limitations

Aside from our study’s strengths, which include the dyadic approach to sexuality in older men and women, robust statistical analysis and a large-scale heterogeneous sample of couples from several European countries, a number of limitations should also be considered. Initially, the countries selected for this study were planned to represent the north, south, west and east of Europe. Due to difficulties in identifying a collaborator from the Eastern Europe and funding constraints, the final choice rather reflected the nationality of research team members. Next, it should be emphasized that the cross-sectional nature of our study does not warrant any implication of causality: the direction of paths (i.e., structural associations) in our mediation model was determined conceptually—not empirically. Although health-related elements of the SA model are more likely to influence sexuality than vice versa, the overall relationship between SA and sexual satisfaction may go in either direction, including bi-directionality. Considering that our goal was to explore the existence of a link between the two constructs, this ambiguity, however, is not a serious impediment to our conclusions.

Another limitation may pertain to study recruitment. In spite of the fact that it was clearly stated during the recruitment process that sexual activity was not a prerequisite for participation, it is possible that the study oversampled couples who were more sexually active and liberal than others. We assessed such selection bias by comparing relevant characteristics of participants in the dyadic subsample to those of individual participants from our study. Controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, no significant differences in the key indicators were observed between the two samples. However, the fact that our sample included couples of different generations (age range in the study was 60–75 years), which likely differ in sexual behaviors and attitudes, may have affected our findings—possibly by attenuating the size of structural associations.

Despite the robustness of APIM, the country samples were underpowered when associations were small. This needs to be taken into account particularly in the context of (nonsignificant) partner effects. Finally, although it has been argued that the Rowe and Kahn model of SA may be better suited for heterosexual than non-heterosexual persons (cf. Van Wagenen et al. 2013; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2015), couple’s sexual orientation was not addressed in this study. The reason was simple: only one person in our sample identified as gay or lesbian, three reported that they were bisexual and 17 checked the category “other.”

Conclusions

The current study represents the first attempt at dyadic analysis of SA and sexual satisfaction using a European cross-cultural sample of aging couples. Significant and consistent associations between SA and sexual satisfaction confirm the importance of sexual satisfaction as a contributing factor to older couples’ SA. Our findings support the validity of the recently proposed three-dimensional measure of SA (Štulhofer et al. 2018) that can be used in future cross-cultural studies and demonstrate a systematic relationship between SA and male and female sexuality. Taking into account the prevalent stereotypes about old age and sexuality, which may affect older couples’ and individuals’ perspectives on sexual life in later life (Knight and Laidlaw 2009), this insight into the systematic relationship between sexual satisfaction and aging well is important for professionals working with aging couples, as well as individuals.

Acknowledgements

The Research Council of Norway fully funded the study (Grant 250637 awarded to the last author).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Arbuckle JL. IBM AMOS 22 user’s guide. Mount Pleasant, SC: Amos Development Corporation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett C, Hinchliff S. Addressing the sexual rights of older people. London: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthén B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:456–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Cole SW, Capitanio JP, Goossens L, Boomsma DI. Loneliness across phylogeny and a call for comparative studies and animal models. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:202–212. doi: 10.1177/1745691614564876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver LF, Buchanan D. Successful aging: considering non-biomedical constructs. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1623–1630. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S117202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 2002;9:233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford M, Popp D. Sexual double standards: a review and methodological critique of two decades of research. J Sex Res. 2003;40:13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J. Sexual expression in later life: a review and synthesis. J Sex Res. 2012;49:125–141. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.603168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte M, Mayer A. Exploring the link between daily relationship quality, sexual desire, and sexual activity in couples. Arch Sex Behav. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fileborn B, Thorpe R, Hawkes G, Minichiello V, Pitts M, Dune T. Sex, desire and pleasure: considering the experiences of older Australian women. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2015;30:117–130. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2014.936722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn T-J, Gow AJ. Examining associations between sexual behaviours and quality of life in older adults. Age Ageing. 2015;44:823–828. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley S. Older adults and sexual health: a review of current literature. Curr Sex Health Reports. 2015;7:70–79. doi: 10.1007/s11930-015-0046-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Shiu C, Goldsen J, Emlet CA. Successful aging among LGBT older adults: physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. Gerontologist. 2015;55:154–168. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data: analysis and design. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Graham CA, Mercer CH, Tanton C, Jones KG, Johnson AM, Wellings K, Mitchell KR. What factors are associated with reporting lacking interest in sex and how do these vary by gender? Findings from the Third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016942. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant DM, Beck JG, Davila J. Does anxiety sensitivity predict symptoms of panic, depression, and social anxiety? Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2247–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman JR, Long JS, Smith SN, Fisher WA, Sand MS, Rosen RC. Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40:741–753. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9703-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliff S, Gott M. Intimacy, commitment, and adaptation: sexual relationships within long-term marriages. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 2004;21:595–609. doi: 10.1177/0265407504045889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliff S, Tetley J, Lee D, Nazroo J. Older adults’ experiences of sexual difficulties: qualitative findings from the English Longitudinal Study on Ageing (ELSA) J Sex Res. 2018;55:152–163. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1269308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett A, Peel E, Shaw RL. Sex and diabetes: a thematic analysis of gay and bisexual men’s accounts. J Health Psychol. 2012;17:409–418. doi: 10.1177/1359105311412838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstäuber M. Factors associated with sexual health and well being in older adulthood. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30:358–368. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, Laidlaw K. Translational theory: a wisdom-based model for psychological intervention to enhance well-being in later life. In: Bengston VL, Gans D, Putney NM, Silverstein M, editors. Handbook of theories of aging. 2. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 693–705. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Glasser DB, Kang J-H, Wang T, Levinson B, Moreira ED, Nicolosi A, Gingell C. A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: findings from the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:145–161. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-9005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Das A, Waite LJ. Sexual dysfunction among older adults: prevalence and risk factors from a nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57–85 years of age. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2300–2311. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DM, Nazroo J, O’Connor DB, Blake M, Pendleton N. Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45:133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0465-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DM, Vanhoutte B, Nazroo J, Pendleton N. Sexual health and positive subjective well-being in partnered older men and women. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71:698–710. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Gavrilova N. Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. BMJ. 2010;340:c810. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BL. Science, medicine and virility surveillance: ‘sexy seniors’ in the pharmaceutical imagination. Sociol Health Illn. 2010;32:211–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Kelly N, Kahana B, Kahana E, Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, Poon LW. Defining successful aging: a tangible or elusive concept? Gerontologist. 2015;55:14–25. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson M, Berridge C. Successful aging and its discontents: a systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontologist. 2015;55:58–69. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KR, Mercer CH, Ploubidis GB, Jones KG, Datta J, Field N, Copas AJ, Tanton C, Erens B, Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Macdowall W, Phelps A, Johnson AM, Wellings K. Sexual function in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) Lancet (London, England) 2013;382:1817–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muise A, Giang E, Impett EA. Post sex affectionate exchanges promote sexual and relationship satisfaction. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43:1391–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muise A, Maxwell JA, Impett EA. What theories and methods from relationship research can contribute to sex research. J Sex Res. 2018;55:540–562. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1421608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr J, Layte R, O’Leary N. Sexual activity and relationship quality in middle and older age: findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) J Gerontol Ser B. 2017 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R, Carr D. Successful aging 2.0: resilience and beyond. J Gerontol Ser B. 2017;72:201–203. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J, Kahn R. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37:433–440. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søgaard HJ, Bech P. Psychometric analysis of Common Mental Disorders-Screening Questionnaire (CMD-SQ) in long-term sickness absence. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:855–863. doi: 10.1177/1403494809344653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe JD, Cooney TM. Examining Rowe and Kahn’s concept of successful aging: importance of taking a life course perspective. Gerontologist. 2015;55:43–50. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WK, Charo L, Vahia IV, Depp C, Allison M, Jeste DV. Association between higher levels of sexual function, activity, and satisfaction and self-rated successful aging in older postmenopausal women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1503–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Træen B, Hovland A. Games people play: sex, alcohol and condom use among urban Norwegians. Contemp Drug Probl. 1998;25:3–48. doi: 10.1177/009145099802500101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Træen B, Carvalheira A, Kvalem IL, Štulhofer A, Janssen E, Graham CA, Hald GM, Enzlin P. Sexuality in older adults (65 +)—an overview of the recent literature, part 2: body image and sexual satisfaction. Int J Sex Health. 2017;29:11–21. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2016.1227012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Træen B, Hald GM, Graham CA, Enzlin P, Janssen E, Kvalem IL, Carvalheira A, Štulhofer A. Sexuality in older adults (65 +)—an overview of the literature, part 1: sexual function and its difficulties. Int J Sex Health. 2017;29:1–10. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2016.1224286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Træen B, Štulhofer A, Janssen E, Carvalheira A, Hald GM, Lange T, Graham C. Sexual activity and sexual satisfaction among older adults in four European countries. Arch Sex Behav. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Schoot R, Lugtig P, Hox J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2012;9:486–492. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2012.686740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagenen A, Driskell J, Bradford J. "I’m still raring to go": successful aging among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. J Aging Stud. 2013;27:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Iveniuk J, Laumann EO, McClintock MK. Sexuality in older couples: individual and dyadic characteristics. Arch Sex Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0651-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woloski-Wruble AC, Oliel Y, Leefsma M, Hochner-Celnikier D. Sexual activities, sexual and life satisfaction, and successful aging in women. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2401–2410. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum (2017) The global gender gap report 2017 insight report. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2017.pdf. Accessed 8 Nov 2017