Abstract

This is a multi-individual (n = 11), stable carbon and nitrogen isotope study of bone collagen (δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol) from the giant beaver (genus Castoroides). The now-extinct giant beaver was once one of the most widespread Pleistocene megafauna in North America. We confirm that Castoroides consumed a diet of predominantly submerged aquatic macrophytes. These dietary preferences rendered the giant beaver highly dependent on wetland habitat for survival. Castoroides’ δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol do not support the hypothesis that the giant beaver consumed trees or woody plants, which suggests that it did not share the same behaviours as Castor (i.e., tree-cutting and harvesting). The onset of warmer, more arid conditions likely contributed to the extinction of Castoroides. Six new radiocarbon dates help establish the chronology of the northward dispersal of the giant beaver in Beringia, indicating a correlation with ice sheet retreat.

Subject terms: Biogeochemistry, Palaeoecology

Introduction

The Pleistocene giant beaver

The one hundred kilogram giant beaver (genus Castoroides) inhabited North America throughout the mid- to late Pleistocene1–3. The giant beaver went extinct along with dozens of other genera during the late Pleistocene megafauna extinction4,5. The underlying mechanism(s) behind this global extinction remains contested, though it is often attributed to a combination of climate change and anthropogenic impacts6–12. Current information regarding giant beaver ecology is insufficient to evaluate various hypotheses posited to be responsible for Castoroides’ extinction. The last appearance date of 10,150 ± 50 years BP for a Castoroides ohioensis specimen from Wayne County, New York demonstrates that it was also one of the late surviving members of the Pleistocene megafauna community in North America6. Here we use stable isotopes to explore the ecology of Castoroides, which allows us to better understand its diet, its impact on the surrounding Pleistocene landscape, and the mechanisms that led to its demise. Previous models of Castoroides’ diet and habitat preference are based on skeletal morphology, fossil depositional environment, and the behaviour of the only remaining extant member of the Castoridae family, Castor.

Extant analogue species

The short limbs and bulky body of Castoroides made it poorly adapted to a life spent predominantly on land and it must have relied on access to the water for shelter from terrestrial predators13. Previous studies based on stable isotope analysis of single specimens suggest that the giant beaver consumed aquatic vegetation, and thrived in mid-latitude regions of North America during warm, strongly seasonal conditions between 125,000 and 75,000 BP14,15. Other studies hypothesize that the giant beaver was a relatively cold-tolerant species, preferentially consumed emergent macrophytes, and lived in ponds and shallow lakes bordered by marshlands16–19. The presence of giant beaver fossils in high latitude regions such as Alaska and Yukon Territory confirm it could persist through harsh arctic climatic and low light conditions in the winter. It is unknown if Castoroides shared any behavioural characteristics with the genus Castor, and the possibility that the giant beaver engineered its habitat by constructing dams or lodges remains a topic of debate1,17,20–24.

Two competing models of Castoroides diet and behaviour have emerged based on extant North American semi-aquatic rodents with well-documented ecologies and distinctly different impacts on the surrounding ecosystem14,19,25–27. The first model predicts that Castoroides filled an econiche similar to that of the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), as a semi-aquatic rodent that primarily consumed submerged and emergent freshwater macrophytes in calm wetlands with an expansive littoral zone14,19–21. Such feeding would have kept shallow waterways clear of excess macrophyte growth and promoted aquatic biotic diversity. The second model suggests that Castoroides filled an econiche similar to that of the extant North American beaver (Castor canadensis), as a semi-aquatic rodent that consumed both terrestrial and aquatic vegetation, and practiced tree-cutting behaviour for the purpose of lodge and dam building25. The bulk of its diet would have been foliage from deciduous trees and its engineering habits would have promoted local biotic diversity and significantly impacted the hydrological patterns of the Pleistocene landscape.

Problematic to the latter hypothesis is that there are neither confirmed discoveries of dam or lodge structures built by giant beavers, nor substantiated evidence of Pleistocene-era cut wood that matches the occlusal surface size and angle of Castoroides incisors28,29. The angle of protrusion of the incisors from the skull and their lack of a thin, chisel-like edge rendered giant beaver incisors ineffective tools for cutting down trees21. This has not stopped speculation that masses of branches discovered in proximity to Castoroides fossils in Pleistocene sediments were built by the giant beaver25. In addition, tree harvesting behaviours have been present in certain branches of the Castoridae family since the Miocene30,31.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes and dietary mixing models

The stable carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions (δ13C and δ15N) of an animal’s body tissues closely reflect those of its diet, with adequately known isotopic discrimination factors occurring between each trophic level32–34. Thus, the isotopic composition of modern and ancient bone collagen serves as a useful proxy for diet35–38. To correctly assess trophic position and forage preference, however, potential dietary sources must be established39.

Here, Castoroides, O. zibethicus and C. canadensis bone collagen carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions (δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol) are assessed within the context of modern terrestrial and freshwater plant carbon and nitrogen isotope signatures. Modern plant samples were collected from shallow lakes, marshes, and creeks located in the Great Lakes region of southwestern Ontario (Pinery Provincial Park and the London area) and Yukon Territory (Whitehorse and Old Crow Basin), Canada, whereas Castoroides specimens originate from sites in Yukon Territory, Canada, and Ohio, USA (Fig. 1). The isotopic data were incorporated into a statistically-based dietary mixing model (SIAR V4: Stable Isotope Analysis in R. An Ecologists’ Guide) to determine both forage choice and relative input proportions for each rodent species40. This allows us to determine the degree of dietary overlap amongst rodent species, Castoroides’ level of dependence on aquatic habitat space, and the viability of using C. canadensis or O. zibethicus as extant analogues in palaeoecological models incorporating the giant beaver. A series of new radiocarbon dates obtained from Castoroides bone collagen from Yukon Territory and Ohio are also reported to evaluate the chronology of regional extirpation.

Figure 1.

Terrain map of North America indicating sample collection sites. 1 – Old Crow, Yukon Territory, Canada. 2 – Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, Canada. 3 – Pinery Provincial Park and London Area, Ontario, Canada. 4 – Ohio, United States of America. Map data from Google, INEGI, 2019.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes of freshwater plants

Carbon and nitrogen dynamics are complex in freshwater systems. As a result, freshwater plant, or macrophyte δ13C and δ15N vary widely39,41–43. Plant physiology and local environmental conditions account for broad-scale isotope variability; site specific characteristics (i.e., wetland habitat type, water turbulence, latitude, local geology, water pH, water temperature) also impact the isotopic composition of bioavailable carbon and nitrogen sources. Habitat division within a wetland also has a strong impact on macrophyte δ13C and δ15N39. Plant functional groups used here (terrestrial trees and shrubs, emergent macrophytes, floating macrophytes, and submerged macrophytes) were categorized not by taxonomic relationship, but by the plant’s exposure to the atmosphere, the water column, and/or substrate. These three media determine which sources of bioavailable carbon and nitrogen the plant can access, and ultimately control plant δ13C and δ15N.

Complexities arising from the use of modern plants in palaeodietary studies

Anthropogenic influence on global or regional carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions at the base of the food web is one concern when utilizing modern plant δ13C and δ15N as a basis for palaeodietary interpretations. Photosynthetic pathway is the dominant control on plant δ13C and atmospheric CO2 is the primary carbon source for photosynthetic organisms. A Suess effect correction can be applied to modern δ13C data to account for the recent addition (primarily through the burning of fossil fuels) of 12C-enriched CO2 to the atmosphere44.

Assessment of the nitrogen isotope baseline is more complicated as it is specific to region and ecosystem. Anthropogenic activities (particularly land development and agricultural practices) can contribute nitrogen sources that enter the local environment and impact the nitrogen isotope composition of primary producers. This effect is particularly pronounced in modern wetland habitats45.

There is also evidence that regional nitrogen isotope baselines of some ecosystems changed over the course of the Quaternary. For instance, the dynamic of the nitrogen cycle and the isotopic composition of the nitrogen baseline in grasslands of Yukon Territory have changed between the Late Pleistocene and the present46. There, Mammoth Steppe plant macrofossil δ15N was on average ~2.8‰ higher than that of modern grassland plants collected from same location46. This 15N-enrichment at the base of the food web was incorporated into successive trophic levels and contributed to unusually high δ15Ncol of Mammoth Steppe grassland herbivores (such as the Arctic ground squirrel and the woolly mammoth)38,46. The plant macrofossil 15N-enrichment was likely the result of an arid climate and a more open nitrogen cycle47. It is less likely, however, that Pleistocene wetland ecosystems experienced such a shift in δ15N.

The 15N-enrichment of the nitrogen baseline observed in the Mammoth Steppe grasslands was induced by factors that would not have been nearly as pronounced in Pleistocene wetland ecosystems, or wetter, forested ecosystems with lower megafauna population densities. Late Pleistocene mastodon and giant beaver populations, for example, were contemporary in Yukon Territory and in the Great Lakes region of North America48,49. These species both showed preference for the same type of habitat (open mix-forest interspersed with wetlands). Mastodon were browsers and their collagen is significantly depleted of 15N relative to Mammoth Steppe fauna that were graminoid and forb specialists (e.g., in North America, average δ15Ncol of mastodon is ~4‰ lower than mammoth)38,50,51. In short, while plant enrichment in 15N arising from aridity and associated shifts in the nitrogen cycle can profoundly affect grassland plants, we posit that pronounced changes are much less likely in plants from forested and wetland habitats. In the absence of unaltered ancient equivalents, modern plants from uncontaminated wetlands or wetter, forested habitats can therefore provide an adequate, if not ideal, proxy for incorporation into isotopic models that simulate Pleistocene dietary preferences.

In addition, the relative nitrogen isotope pattern of each plant functional group should remain the same, despite changes in nitrogen baseline δ15N. Aquatic plants (submerged, emergent, and floating macrophytes), for example, should have, on average higher δ15N than terrestrial plants on account of their access to more 15N-enriched sources of bioavailable nitrogen.

Results

Radiocarbon dates

Six new radiocarbon dates obtained from Castoroides bone and dentin collagen are reported in Table 1. Bone collagen from Castoroides that lived at high latitudes north of the Arctic Circle yielded dates that are analytically non-finite or so close to the analytical limit of radiocarbon dating (~45,000 14C years BP) that they can be treated as non-finite ages. An additional summary of Castoroides radiocarbon dates from the literature is presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Radiocarbon ages for Castoroides specimens (bone and tooth dentin collagen) analyzed in this study.

| Project sample ID | Institute accession ID | Specimen locality | 14C age (BP) | ± | AMS Lab code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3-TP2014 | CMN 18306 | Old Crow Basin, Yukon Territory | >44,600 | UCIAMS151528 | |

| C4-TP2014 | CMN 18707 | Old Crow Basin, Yukon Territory | >43,700 | UCIAMS151529 | |

| C6-TP2014 | CMN 14711 | Old Crow Basin, Yukon Territory | 44,600 | 2600 | UCIAMS151530 |

| C8-TP2014 | CMN 33640 | Old Crow Basin, Yukon Territory | >42,200 | UCIAMS151531 | |

| C11-TP2014 | OHS N9087 | Williams County, Ohio | 11,961 | 80 | AA105557 |

| C22-TP2014 | OHS N8739 | Harmony Township, Ohio | 11,168 | 53 | AA105559 |

Table 2.

Literature summary of Castoroides radiocarbon dates.

| Taxon | Specimen locality | Tissue type | 14C age (BP) | ± | AMS Lab Code | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castoroides ohioensis | Fairy Hole Rockshelter, Allamuchy Township, Warren Co., New Jersey | Molar (collagen) | 11,140 | 30 | UGAMS-16240 | Boulanger et al.65 |

| Castoroides ohioensis | Big Brook locality, Holmdel Township, Monmouth Co., New Jersey | Molar (bioapatite) | 13,210 | 30 | UGAMS-18142 | Boulanger et al.65 |

| Castoroides ohioensis | Dutchess Quarry Cave 8, Orange Co., New York | Molar (collagen) | 11,670 | 70 | NSRL-1513 | Steadman et al.96 |

| Castoroides | Clyde, Wayne Co., New York | Bone (collagen) | 10,150 | 50 | OS-73632 | Fernac and Kozlowski97 |

| Castoroides | Kansas River, Johnson Co., Kansas | Mandible (collagen) | 12,150 | 80 | CAMS-20004 | McDonald and Glotzhober66 |

| Castoroides | Mississippi River, Ramsey Co., Minnesota | Bone (collagen) | 10,320 | 250 | not provided | Erickson98 |

| Castoroides | Clear Creek, Fairfield Co., Ohio | Mandible (collagen) | 12,040 | 35 | UCLAMS-11219 | McDonald and Glotzhober66 |

| Castoroides | Sheriden Pit, Wyandott Co., Ohio | Bone (collagen) | 10,850 | 60 | CAMS-26783 | Tankersley and Landefeld99 |

Collagen preservation

Collagen yield (wt. %), atomic C:N ratio, and carbon and nitrogen contents (wt. %) were used to assess collagen preservation in all three rodent species (Tables 3 to 5). All Castoroides specimen parameters are within the accepted range for archaeological skeletal material from temperate or polar regions (collagen yield > 1%; %C = 34.8 ± 8.8%; %N = ~11–16%; C:N = 3.1–3.5)52.

Table 3.

Castoroides specimen information and stable isotope results. Values in bold indicate mean and 1 SD where duplicate analyses were completed for the same specimen.

| Project sample ID | Institute accession ID | Specimen locality | Skeletal element | δ13Ccol (‰, VPDB) | δ15Ncol (‰, AIR) | C (wt. %) | N (wt. %) | Collagen yield (wt. %) | Atomic C:N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1-TP2014 | CMN 16657 | Old Crow Basin, YT | Humerus | −21.2 | +6.3 | 41.7 | 15.6 | 1.4 | 3.1 |

| C3-TP2014 | CMN 18306 | Old Crow Basin, YT | Pelvis | −19.1 ± 0.3 | +1.9 ± 0.1 | 41.5 | 15.2 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| C4-TP2014 | CMN 18707 | Old Crow Basin, YT | Tibia | −10.7 ± 0.2 | +5.7 ± 0.1 | 41.8 | 15.5 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| C5-TP2014 | CMN no ID | Old Crow Basin, YT | Femur | −18.5 | +7.7 | 41.2 | 15.7 | Data not provided* | 3.1 |

| C6-TP2014 | CMN 14711 | Old Crow Basin, YT | Humerus | −16.0 | +6.0 | 33.1 | 11.9 | 1.1 | 3.2 |

| C7-TP2014 | CMN 14781 | Old Crow Basin, YT | Long bone diaphysis | −14.0 | +7.4 | 39.6 | 14.5 | Data not provided* | 3.2 |

| C8-TP2014 | CMN 33640 | Old Crow Basin, YT | Humerus | −12.4 ± 0.2 | +6.2 ± 0.0 | 39.7 | 14.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| C9-TP2014 | CMN 43178 | Old Crow Basin, YT | Femur | −21.2 | +6.8 | 42.7 | 15.5 | Data not provided* | 3.2 |

| C10-TP2014 | OHS N9109 | Clear Creek Township, OH | Mandible | −20.2 ± 0.1 | +5.6 ± 0.1 | 35.5 | 12.6 | 3.1 | 3.3 |

| C11-TP2014 | OHS N9087 | Williams County, OH | Mandible | −20.6 ± 0.1 | +4.5 ± 0.1 | 40.0 | 14.3 | 11.2 | 3.3 |

| C22-TP2014 | OHS N8739 | Harmony Township, OH | Incisor (dentin) | −19.5 | +5.4 | 37.4 | 13.5 | 3.8 | 3.2 |

*Collagen extraction performed at the Keck Carbon Cycle AMS Facility at the University of California, Irvine for radiocarbon dating. Remaining collagen material was returned for stable isotope analysis at the University of Western Ontario.

Table 5.

Castor canadensis specimen information and stable isotope results. Specimens collected between August 2013 and August 2014. Stable carbon isotope data are not corrected for the Suess effect.

| Project sample ID | Specimen locality | Skeletal element | δ13Ccol (‰, VPDB) | δ15Ncol (‰, AIR) | C (wt. %) | N (wt. %) | Collagen yield (wt. %) | Atomic C:N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1-TP2013 | Inverhuron, ON | Tibia | −23.6 | +7.1 | 43.9 | 16.9 | 12.0 | 3.0 |

| B2-TP2013-A | Dawson City, YT | Metapodial | −24.0 | +3.4 | 44.8 | 16.9 | 10.2 | 3.1 |

| B3-TP2014-1 | New Liskeard, ON | Mandible | −23.7 | +2.0 | 43.6 | 16.6 | 14.4 | 3.1 |

| B4-TP2014-1 | New Liskeard, ON | Mandible | −23.1 | +9.5 | 43.6 | 16.7 | 14.7 | 3.0 |

| B5-TP2014 | New Liskeard, ON | Mandible | −23.2 | +8.0 | 42.7 | 16.3 | 14.8 | 3.1 |

| B6-TP2014-1 | Whitehorse, YT | Mandible | −23.7 | +2.0 | 43.7 | 16.8 | 16.7 | 3.0 |

| B7-TP2014 | Whitehorse, YT | Mandible | −23.3 | +1.4 | 43.1 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 3.0 |

| B8-TP2014-1 | Whitehorse, YT | Mandible | −23.7 | +2.2 | 42.3 | 16.2 | 16.3 | 3.0 |

Stable isotopes of bone and dentin collagen

Castoroides (n = 11) δ13Ccol ranges from −21.2 to −10.9‰, with a mean of −17.6‰; Castoroides δ15Ncol ranges from +1.9 to +7.7‰, with a mean of +5.8‰ (Table 3). Extant O. zibethicus (Table 4) and C. canadensis (Table 5) show distinctly different isotopic patterns. The carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions of muskrat bone collagen closely resembles that of Castoroides; O. zibethicus (n = 12) δ13Ccol = −22.7 to −10.7‰, with a mean of −15.3‰, and O. zibethicus δ15Ncol = +2.2 to +6.6‰, with a mean of +5.1‰. C. canadensis (n = 8) δ13Ccol varies very little, ranging from −24.0 to −23.2‰, with a mean of −23.5‰. C. canadensis δ15Ncol displays more variation, ranging from +1.4 to +9.5‰, with a mean of +4.5‰.

Table 4.

Ondatra zibethicus specimen information and stable isotope results. Values in bold indicate mean and 1 SD when duplicate analyses were performed for the same specimen. Specimens collected between August 2013 and August 2014. Stable carbon isotope data are not corrected for the Suess effect.

| Project sample ID | Specimen locality | Skeletal element | δ13Ccol (‰, VPDB) | δ15Ncol (‰, AIR) | C (wt. %) | N > ((wt. %) | Collagen yield (wt. %) | Atomic > C:N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1-TP2013 | London, ON | Mandible | −22.7 | +5.0 | 41.1 | 15.5 | 8.6 | 3.1 |

| M3-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −13.6 | +5.3 | 42.6 | 14.9 | 11.8 | 3.3 |

| M4-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −14.2 | +2.2 | 42.1 | 16.1 | 12.2 | 3.0 |

| M5-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −17.5 | +3.8 | 42.5 | 14.9 | 10.8 | 3.3 |

| M6-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −22.0 | +5.9 | 42.5 | 16.1 | 13.3 | 3.1 |

| M7-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −15.1 | +6.1 | 42.6 | 16.2 | 11.3 | 3.1 |

| M8-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −14.6 | +3.9 | 43.2 | 15.1 | 13.4 | 3.3 |

| M9-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −14.3 | +6.6 | 42.8 | 14.3 | 13.3 | 3.5 |

| M10-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −15.0 | +5.3 | 43.2 | 16.4 | 12.7 | 3.1 |

| M11-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −12.6 | +5.7 | 43.6 | 16.7 | 13.5 | 3.0 |

| M13-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −10.7 ± 0.1 | +6.0 ± 0.0 | 42.6 | 14.9 | 13.7 | 3.3 |

| M14-TP2014 | Old Crow Flats, YT | Mandible | −11.7 | +4.7 | 42.8 | 15.0 | 12.8 | 3.3 |

Stable isotopes of plants

Modern plant sample δ13C and δ15N are listed in Tables A and B in Supplementary Information File SI1. A summary of plant functional group δ13C and δ15N mean and range are presented in Table C in Supplementary Information File SI1. Generally, macrophytes have higher δ13C and δ15N than terrestrial plants. Submerged macrophytes display a bimodal distribution of δ13C (ranging from −41 to −13‰). These isotopic patterns are demonstrated in Figure A in Supplementary Information File SI1.

Discussion

Our terrestrial and freshwater plant δ13C and δ15N results are consistent with those of other studies from comparable regions53,54. While we do not have the perfect stable isotope dietary mixing model (i.e., one comprising coeval plant macrofossil and faunal material from the same site), modern plant sampling sites were purposefully chosen that had minimal observed or documented anthropogenic impact. Anthropogenic impact on the nitrogen cycle and isotopic composition of wetland habitats in Pinery Provincial Park is minimal55. Plant samples from London, Ontario (n = 9) were collected from non-urban areas. While we cannot rule out that the δ15N of these nine samples may have been impacted by agriculture, chemical fertilizer (δ15N ≈ 0‰) is dominantly used in this region, which constrains possible variation from that source56. Yukon Territory has very low human population density (<36,000), and minimal industrial and agricultural activities57. As such, we expect minimal influence on bioavailable sources of nitrogen (i.e., septic effluent, chemical, manure) and δ15N of plants collected around Whitehorse and Old Crow.

In addition, the majority of the plant taxa included in this study (see plant taxonomic information in Supplementary Information File SI1 Tables A and B) are known to have existed in North America during the late Pleistocene (refer to19,58–60 for examples of plant macrofossil and pollen records recovered from Pleistocene sites from Beringia and the Great Lakes region). Plants sampled also included tree and macrophyte species documented as part of the diet of extant C. canadensis and O. zibethicus61–64. All this said, a great opportunity remains to further test the ideas presented here through isotopic analysis of contemporary Pleistocene plant macrofossils associated with Castoroides.

Overall, collagen yields from giant beaver specimens were relatively low. This was particularly surprising for Castoroides specimens collected from Old Crow, Yukon Territory. Pleistocene faunal remains from Beringian deposits typically have excellent organic molecule preservation. We propose that the low collagen yields are in fact linked to giant beaver habitat preference. Castoroides remains are most commonly recovered from active or ancient wetland environments19,65,66. In addition, specimens from the Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) collections included in this study were recovered from the banks of the Porcupine River, Yukon Territory, as reported by C.R. Harington. Given its semi-aquatic nature, most giant beavers likely died in close proximity to a wetland habitat. The composite nature of bone (bioapatite crystals interlocked with strands of collagen protein) results in a structure where the mineral component protects the protein component (particularly from detrimental microorganism enzyme activity)67. Exposure to water in a post-mortem depositional environment, however, accelerates bone diagenetic processes. The deposition of giant beaver skeletal material in an aqueous environment accelerates dissolution of the bioapatite, after which it can no longer protect the organic fraction and collagen loss is more likely to occur.

A Suess effect correction of 2.1‰ was applied to modern rodent δ13Ccol and to the δ13C of plants collected in 2014. A correction of 1.7‰ was applied to the δ13C of plants collected in 2000. Refer to Supplementary Information File SI1 Table A and B for plant sample collection dates. The corrections were calculated using data available through the Scripps CO2 monitoring program and the δ13C of late Pleistocene atmospheric CO2 described in Schmitt et al.68,69. The Suess effect correction was applied when modern δ13C data were incorporated into the SIAR mixing model.

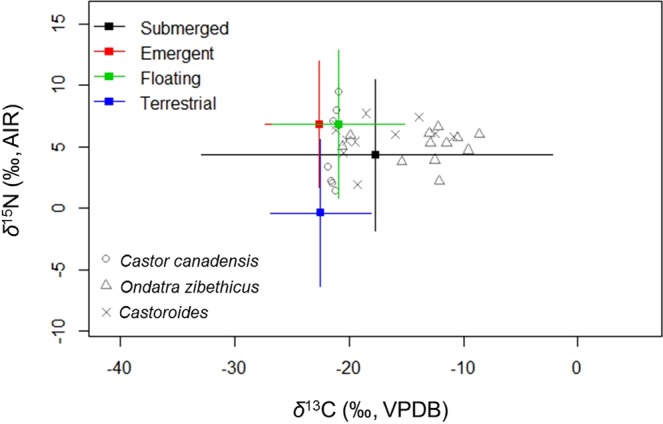

Based on existing literature, collagen-diet offsets of +4.2‰ and +3.0‰ were utilized for δ13C and δ15N, respectively33,70–72. Collectively, the corrections for the Suess effect and dietary isotopic discrimination render the rodent δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol directly comparable to the plant isotopic data incorporated into the SIAR mixing model (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions of rodent collagen and vegetation. Rodent δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol are corrected for trophic enrichment factors to render them comparable to the four plant functional groups (represented by their mean and a range of 2 SD) that may have comprised their diet. Carbon isotope data for modern plants and rodents are corrected for the Suess effect to enable direct comparison with results for Castoroides.

The plant functional groupings (terrestrial trees and shrubs, emergent, floating, and submerged macrophytes) were statistically defined using scripts in SIBER in R Studio 3.1.2 (Figure B and C in Supplementary Information File SI1). The Total Area Convex Hull and Standard Ellipse plots aid in identifying the niche size and relative position of each plant functional group. The relative contribution of each plant functional group to the diet of each rodent species was assessed using scripts from SIAR V4 in R Studio 3.1.2 (Stable Isotope Analysis in R: An Ecologist’s Guide)40.

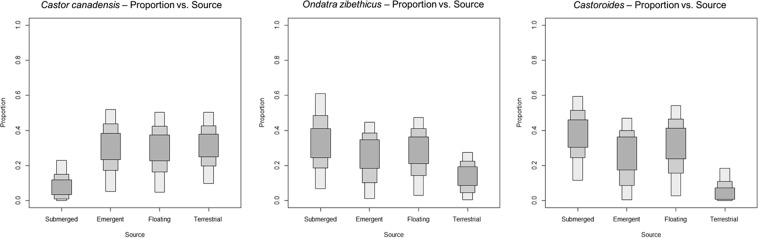

The Proportion versus Source boxplot for Castoroides indicates that submerged and floating macrophytes were central to giant beaver diet, while terrestrial forage sources were utilized sparingly (Fig. 3; see Table C in Supplementary Information File SI1 for plant functional group mean and range). This pattern is a striking contrast to the Proportion versus Source boxplot for C. canadensis (Fig. 3). This suggests that the giant beaver and its smaller cousin had complementary forage preferences and were not in direct competition for the same food resources. Overall, submerged macrophytes appear to contribute a greater proportion to the diet of the giant beaver than they do to the diet of the extant muskrat or beaver.

Figure 3.

Proportion versus Source boxplots generated in SIAR for C. canadensis, O. zibethicus, and Castoroides. Each boxplot represents the relative proportion that each plant functional group (categorized here as a “Source”) contributed to the diet of each rodent species. The carbon isotope data for modern plants and rodents are corrected for the Suess effect.

The Proportion versus Source boxplot for C. canadensis (Fig. 3) indicates a diet composed primarily of terrestrial browse, and emergent and floating macrophytes. This correlates well with what is known about modern beaver diet (extensive consumption of tree foliage and floating macrophyte rhizomes)62–64.

The Proportion versus Source boxplot for O. zibethicus (Fig. 3) indicates a diet composed of approximately equal proportions of each macrophyte type, with a small proportion of terrestrial material. It appears that floating and submerged macrophytes are more integral to muskrat diet that previously reported73,74.

The Castoroides δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol support the hypothesis that the giant beaver was a semi-aquatic rodent that grazed predominantly on aquatic macrophytes. Our δ13Ccol results are consistent with Boulanger et al.’s report of Castoroides (tooth dentin, n = 1) δ13Ccol = −21.3‰65. Additional comparisons between modern and Pleistocene Castor and Ondatra δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol would strengthen these conclusions. Unfortunately, there is very little published stable isotope data available from Pleistocene Castor and Ondatra specimens. There are isotopic data for a handful of samples (Castor n = 2; Ondatra n = 4) from the Aucilla River, Florida75; however, the bone collagen carbon and nitrogen contents indicates poor preservation, and hence the isotopic results may not record original compositions. Further analyses are required to make an effective comparison.

A strong preference for submerged macrophytes rendered Castoroides highly dependent on wetland habitat for sustenance. The Proportion versus Source boxplots generated in SIAR strongly suggest that C. canadensis and Castoroides occupied complementary dietary niches. While they likely competed for habitat space, their forage preferences were sufficiently different to allow the two genera to co-exist across North America during the mid- to late Pleistocene. When assessing Castoroides’ impact on the Pleistocene landscape, neither C. canadensis nor O. zibethicus constitute a perfect analogue species; however, based on δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol results, the muskrat is the closest extant semi-aquatic rodent that could be used to describe the diet and ecological impact of the giant beaver. These interpretations remain supported even if only δ13Ccol are compared among the three rodent species (refer to Figure D in Supplementary Information File SI1).

The Proportion versus Source boxplots generated in SIAR do not lend support to the notion that Castoroides cut down trees or consumed foods such as tree leaves, bark or twigs. There is currently no convincing evidence of dams, lodges, or underwater food caches constructed by giant beavers from the Pleistocene sedimentological record. If the giant beaver was felling trees for food, the stable isotopic composition of its bone collagen should reflect a greater proportion of terrestrial browse (see Supplementary Information File SI1 Table C for plant functional group δ13C and δ15N means and ranges). This conclusion is further supported by skeletal morphology, in that giant beaver incisors lack the chisel-like edge that is characteristic of Castor incisors76 (Fig. 4). C. canadensis’ ability to engineer the landscape and to create new habitat space, combined with the rise in abundance and diversity of deciduous tree species in north-eastern North America, likely gave Castor a distinct advantage over the giant beaver during the late Pleistocene. Hence competition for habitat space may have been a contributing factor in the extinction of the giant beaver. Testing this hypothesis, however, awaits a suitable suite of fossil remains of coeval Castor and Castoroides.

Figure 4.

Left: A near-complete Castoroides ohioensis mandible and lower incisor from Clear Creek Township, Ohio, USA. Specimen OHS N9109. Right: A complete Castoroides ohioensis upper incisor from Old Crow, Yukon Territory, Canada. Specimen CMN 51270. Photographs by T. Plint.

Confirmation that Castoroides was highly dependent on wetland habitat not only for shelter from predators, but also for food allows us to assess its extinction within the context of changing environmental conditions during the late Pleistocene. The loss of both wetland habitat in lowland regions and associated open mixed-conifer forests coincide with the regional disappearance of Castoroides populations in many areas across North America, as is discussed next.

The first appearance of Castoroides in the fossil record is in Florida and dates to the Irvingtonian I NALMA (1.9 mya to 900,000 BP)2,77,78. There is a more or less continuous record of Castoroides in the southeast, where the oldest known species of giant beaver, Castoroides leiseyorum, is assumed to have given rise to both Castoroides ohioensis and Castoroides dilophidus79. Unlike C. ohioensis, it appears that C. dilophidus remained confined to the southeast (Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia) during the Rancholabrean NALMA (240,000 to 11,000 year BP)79,80. Virtually all specimens from Florida have been collected from river systems and many lack precise contextual information80. An insecure faunal chronology, combined with scarce pollen and plant macrofossil records for the region prior to the Wisconsin Glaciation, limit our ability to discern ecological patterns over time. However, the region supported forested swamps and warm-adapted mixed forests during much of the mid-Wisconsin. Florida underwent multiple periods of increasing aridity and more seasonal precipitation patterns throughout the Last Glacial Maximum (approximately 24,000 years BP)81. Scrub and prairie conditions arose in parts of Georgia, the Coastal Plain, and in southern Florida during both Wisconsin glacial and post-glacial times82. Moister conditions that favoured pine forests and swampland did not return until mid- to late Holocene, long after the extinction of the giant beaver81–83.

The first records of Castoroides in the Great Plains region are from Kansas and date to the Irvingtonian NALMA. However, the transition from an ancestral taxon Procastoroides (uncrenulated incisors) to Castoroides (crenulated incisors) probably occurred on the Great Plains during either the late Pliocene or the early Pleistocene during the Blancan NALMA2,84. Giant beaver populations became well-established across Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma during the late Irvingtonian and early Rancholabrean NALMA1,80. After onset of the Illinoian glaciation, giant beaver fossils disappeared from the Great Plains record and became concentrated east of the Mississippi River. The disappearance of no-analog forest communities, the regional extinction of certain conifer tree species, and the appearance of grass or herb plant communities all correlate to increasing aridity and coincide with the disappearance of the giant beaver in the region85–87.

In the north, Castoroides and Castor fossils are both found in lake bed and river deposits from the unglaciated region of Old Crow, Yukon Territory88. Giant beavers most likely inhabited Yukon Territory and Alaska during global warm periods between 200,000 to 75,000 years BP89,90. This chronology is similar to that of the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) and western camel (Camelops hesternus) and are interpreted to represent northward dispersals during the relatively warm Sangamonian interglaciation49,91. The presence of Castoroides fossils from in situ deposits correlative to Marine Isotope Stage 7 (~200,000 years BP) suggests there were repeated northward dispersals into the Arctic during at least two separate interglaciations89. Giant beaver populations could only have spread northward during these periods of warm climate, where the retreat of the ice sheets left a string of meltwater wetlands, and boreal forests and wet-tundra were established regionally. The presence of Castoroides in these arctic latitudes suggests they were capable of surviving the cold dark winters of interglacial periods, though regional aridification and establishment of cryoxerophilous steppe tundra vegetation probably created environments that were not habitable for them during glacial periods. It is highly likely that the giant beaver was regionally extirpated with the establishment of Wisconsinan glacial conditions around 70,000 years BP and subsequently all populations were restricted to areas south of the continental ice sheets until their final demise at the end of the Pleistocene90.

Radiocarbon dates from Ohio and New York indicate that the Great Lakes Basin was home to the last known population of giant beavers65. Fossils from the Sangamonian are also occasionally found. The population was concentrated south of the fluctuating continental ice sheet margin during the Wisconsinan glacial period prior to the extinction of the genus1,17–19,65,66. The giant beaver disappeared from Eastern North America shortly before the Pleistocene-Holocene transition6. With the disappearance of this population, the genus became globally extinct.

Wisconsinan age giant beaver fossils are more commonly associated with sediments from warmer interstadial times, when the retreat of continental ice sheets left the Great Lakes region flooded with meltwater. The cool, moist climate during the mid-Wisconsinan provided ideal habitat space in the form of extensive lacustrine environments surrounded by forest communities dominated by spruce and larch19,58. During the onset of the Holocene warm period, much of the shallow wetland habitat in Eastern North America became in-filled with sediment and deciduous trees replaced much of the open mixed-conifer forest communities92.

The only known instance of direct temporal and spatial overlap between human artifacts and Castoroides fossils occurs in New York State. The current youngest known Castoroides specimen (dating to 10,150 ± 50 years BP) indicates that megafauna populations overlapped with Palaeoindian culture for up to a thousand years6. However, there is no current zooarchaeological evidence that humans butchered, hunted, or otherwise utilized the giant beaver as a resource.

Conclusions

Castoroides δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol indicate that giant beaver diet was composed predominantly of macrophytes (particularly submerged macrophytes), rendering the genus highly dependent on wetland habitat for survival. The presence of giant beaver fossils coincides with palaeoenvironmental conditions that supported ample swamps and shallow lakes, and such remains disappear in settings associated with the arrival of warmer, more arid conditions. Sediment infilling, loss of glacial meltwater, the onset of more seasonal precipitation patterns, and increased temperature all contributed to wetland habitat loss across North America during this time. Without apparent refugia, Castoroides dwindled to an isolated population located in the lowlands south of the Great Lakes, where potential competition for habitat space and ongoing profound climate change contributed to their extinction.

Methodology

Rodent sample material

Castoroides specimens originating from Yukon Territory, Canada, and Ohio, USA, were included to determine regional differences in diet (Fig. 1). Modern muskrat and beaver skeletal material were included to explore similarities in econiche and the accuracy of the SIAR mixing model. To facilitate comparison, the modern O. zibethicus and C. canadensis samples were sought from similar locations as the Castoroides fossils (Fig. 1, Tables 3 to 5). Modern skeletal materials were donated by conservation authorities, trappers, and ecological research groups.

Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon (14C) dating of Castoroides bone samples collected in Yukon Territory was performed at the Keck Carbon Cycle AMS Facility, University of California Irvine. The Keck laboratory employed ultrafiltration of the gelatinized collagen at 30 kDa, and a second time at 3 kDa to remove exogenous organic material93. Radiocarbon dating of Castoroides bone samples collected in Ohio was performed by the Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, University of Arizona using a modified Longin bulk collagen extraction method without ultrafiltration94.

Collagen stable isotope analysis

Detailed information regarding collagen sample preparation and stable isotope analysis is provided in Supplementary Information File SI1. In brief, collagen was extracted using a modified Longin method94. Crushed sample material underwent lipid extraction, followed by slow demineralization in a weak acid, and a final soak in a weak base to remove humic acids. Gelatinized collagen was analyzed using a Costech Elemental Analyzer coupled with a Thermo Scientific Delta Plus XL isotope ratio mass spectrometer operated in continuous-flow mode with helium as the carrier gas. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope results are reported relative to VPDB and AIR, respectively.

Stable isotope analysis of plants

An assessment of bulk plant carbon and nitrogen isotope signatures was undertaken to provide the necessary context to interpret Castoroides, C. canadensis and O. zibethicus δ13Ccol and δ15Ncol. Supplementary Information File SI1 provides detailed information regarding plant sample taxonomic identification, preparation, and stable isotope analysis performed for this purpose. We analyzed four plant functional groups: terrestrial trees and shrubs, emergent macrophytes, floating macrophytes, and submerged macrophytes. These groupings were chosen to (1) identify plants with access to similar pools of bioavailable carbon and nitrogen, and (2) to gauge Castoroides’ level of dependence on freshwater versus terrestrial food resources. Similar plant functional groupings are utilized in studies of modern C. canadensis54,95.

Modern plant samples were collected from shallow lakes, marshes, and creeks located in southwestern Ontario (Pinery Provincial Park and the London area) and Yukon Territory (Whitehorse and Old Crow Basin), Canada (Fig. 1).

The Ontario sites experience a temperate climate, and with annual average precipitation of approximately 1000 mm. Pinery Provincial Park is located on the south-east shore of Lake Huron. The park consists of the northern-most extension of the Oak Savannah ecosystem and overlays a succession of ancient dune ridges. London is located approximately 70 km east of Pinery Provincial Park, and is located in an area of Quaternary sediments (glacial till interbedded with interglacial lake sediments) overlaying Paleozoic limestone bedrock. The sites in Yukon Territory experience a subarctic climate, where annual average precipitation is between 200 and 300 mm. Whitehorse is located within the Whitehorse trough (an intermontane basin) in south-central Yukon Territory. The Old Crow community is located in a region of continuous permafrost within the Arctic Circle and is situated along the southern fringe of the Old Crow Flats (a plain filled with thermokarst lakes). The region is surrounded by adjacent mountain ranges and remained unglaciated during the Quaternary.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following people for their assistance: Jane Bowles, Michael Burzynski, Mike Dorland, Li Huang, Kim Law, Natalia Rybczynski, Rachel Schwartz-Narbonne, Racel Sopoco, Farnoush Tahmasebi, Michelle Viglianti, and Grace Yau. We also thank the following institutions and individuals who provided sample material: Canadian Museum of Nature, Ohio Historical Society, Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Government, Yukon Trappers Association, Long Point Conservation Authority, Wildlife Energetics and Ecology Lab (McGill University), Natasha Bumstead, Bill Fitzgerald, and Tom Porawski. This research was supported by funding from the following organizations: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant (F.J.L.), The Faculty of Science (The University of Western Ontario) (T.P.), Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s (T.P.), Northern Training Grant from the Northern Scientific Training Program (T.P.), and Arcangelo Rea Family Foundation (T.P.). The L.S.I.S. infrastructure used in this research was funded in part by The Canada Foundation for Innovation (F.J.L.), Ontario Research Fund (F.J.L.), and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Tools and Infrastructure grants (F.J.L.). Additional time for research (F.J.L.) was supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program. This is Laboratory for Stable Isotope Science (LSIS) Contribution #363.

Author Contributions

T.P. conducted the sampling and isotopic analyses, interpreted the data, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. F.J.L. and T.P. conceived the research design. G.Z. provided funding for some of the radiocarbon analyses. F.J.L. and G.Z. revised the manuscript and provided valuable comments and advice. F.J.L. provided funding to support the research.

Data Availability

The authors declare no limitations on data or standard operating protocol availability.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/6/2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-43710-9.

References

- 1.Cahn A. Records and distribution of the fossil beaver, Castoroides ohioensis. J. Mammal. 1932;12:229–241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin RA. Taxonomy of the giant Pleistocene beaver Castoroides from Florida. J. Paleontol. 1969;43:1033–1041. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds PS. How big is a giant? The importance of method in estimating body size of extinct mammals. J. Mammal. 2002;83:321–332. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnosky AD, Koch PL, Feranec RS, Wing SL, Shabel AB. Assessing the causes of late Pleistocene extinctions on the continents. Science. 2004;306:70–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1101476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faith JT, Surovell TA. Synchronous extinction of North America’s Pleistocene mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:20641–20645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908153106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulanger MT, Lyman RL. Northeastern North American Pleistocene megafauna chronologically overlapped minimally with Paleoindians. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2014;85:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen TJ, et al. Hydrological transformation coincided with megafaunal extinction in central Australia. Geology. 2015;43:195–198. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper A, et al. Abrupt warming events drove Late Pleistocene Holarctic megafaunal turnover. Science. 2015;349:602–606. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabanus-Wallace MT, et al. Megafaunal isotopes reveal role of increased moisture on rangeland during late Pleistocene extinctions. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017;1:1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guthrie RD. New carbon dates link climatic change with human colonization and Pleistocene extinctions. Nature. 2006;441:207–209. doi: 10.1038/nature04604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louys J, Curnoe D, Tong H. Characteristics of Pleistocene megafauna extinctions in Southeast Asia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007;243:152–173. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pushkina D, Raia P. Human influence on distribution and extinctions of the late Pleistocene Eurasian megafauna. J. Hum. Evol. 2008;54:769–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds PS. Size, shape, and surface area of beaver, Castor canadensis, a semiaquatic mammal. Can. J. Zoo. 1993;71:876–882. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins BS. Ancient beavers did not eat trees. Science News. 2009;176:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuart-Williams HLQ, Schwarcz HP. Oxygen isotopic determination of climatic variation using phosphate from beaver bone, tooth enamel, and dentine. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1997;61:2539–2550. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harington, C. R. The giant beaver. Neotoma 20 (1986).

- 17.Holman, J. A. Ancient life of the Great Lakes Basin: Precambrian to Pleistocene. (University of Michigan Press, 1995).

- 18.Gregory McDonald H, Bryson RA. Modeling Pleistocene local climatic parameters using macrophysical climate modeling and the paleoecology of Pleistocene megafauna. Quat. Int. 2010;217:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swinehart AL, Richards RL. Palaeoecology of a northeast Indiana wetland harboring remains of the Pleistocene giant beaver (Castoroides ohioensis) Proc. Indiana Acad. Sci. 2001;110:151–166. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurtén, B. & Anderson, E. Pleistocene Mammals of North America. (Columbia University Press, 1980).

- 21.Stirton, R. A. Cranial morphology of Castoroides. Mining and Metallurgical Institute, Dr. D. N. Wadia Commemorative Volume, 273–285 (1965).

- 22.Hay, O. P. The recognition of Pleistocene faunas. Smithson. Inst (1912).

- 23.McDonald, H. G. The late Pleistocene vertebrate fauna in Ohio: co-inhabitants with Ohio’s Paleoindians. The first discovery of America: Archaeological evidence of the early inhabitants of the Ohio area. Ohio Archaeol. Counc 23–39 (1994).

- 24.Moore J. Concerning a skeleton of the great fossil beaver. Castoroides ohioensis. Cincinnati Soc. Nat. Hist. 1890;13:138–169. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller RF, Harington CR, Welch R. A giant beaver fossil (Castoroides ohioensis Foster) fossil from New Brunswick, Canada. Atlantic Geology. 2000;36:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovegrove BG, Mowoe MO. The evolution of mammal body sizes: Responses to Cenozoic climate change in North American mammals. J. Evol. Biol. 2013;26:1317–1329. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson, E. Who’s who in the Pleistocene. A mammalian bestiary. (University of Arizona Press, 1984).

- 28.Hillerud, J. M. New specimens of Castoroides ohioensis from Ohio. In Abstracts: Annual meeting of Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Mass (1975).

- 29.Rybczynski N. Castorid phylogenetics: Implications for the evolution of swimming and tree-exploitation in beavers. J. Mamm. Evol. 2007;14:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rybczynski N. Woodcutting behavior in beavers (Castoridae, Rodentia): estimating ecological performance in a modern and a fossil taxon. Paleobiology. 2008;34:389–402. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tedford RH, Harington CR. An Artic mammal fauna from the Early Pleiocence of North America. Nature. 2003;425:388–390. doi: 10.1038/nature01892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly JF. Stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in the study of avian and mammalian trophic ecology. Can. J. Zool. 2000;78:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bocherens H, Drucker D. Trophic level isotopic enrichment of carbon and nitrogen in bone collagen: Case studies from recent and ancient terrestrial ecosystems. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2003;13:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krajcarz MT, Krajcarz M, Bocherens H. Collagen-to-collagen prey-predator isotopic enrichment (Δ13C, Δ15N) in terrestrial mammals - a case study of a subfossil red fox den. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018;490:563–570. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bocherens H. Isotopic biogeochemistry and the paleoecology of the mammoth steppe fauna. Deinsea. 2003;9:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coltrain JB, et al. Rancho la Brea stable isotope biogeochemistry and its implications for the palaeoecology of late Pleistocene, coastal southern California. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2004;205:199–219. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox-Dobbs K, Leonard JA, Koch PL. Pleistocene megafauna from eastern Beringia: Paleoecological and paleoenvironmental interpretations of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope and radiocarbon records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2008;261:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metcalfe JZ, Longstaffe FJ, Hodgins G. Proboscideans and paleoenvironments of the Pleistocene Great Lakes: Landscape, vegetation, and stable isotopes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013;76:102–113. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casey MM, Post DM. The problem of isotopic baseline: Reconstructing the diet and trophic position of fossil animals. Earth-Science Rev. 2011;106:131–148. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inger, R., Jackson, A., Parnell, A. & Bearhop, S. SIAR V4: Stable Isotope Analysis in R. An Ecologist’s Guide (2010).

- 41.Chappuis E, Seriñá V, Martí E, Ballesteros E, Gacia E. Decrypting stable-isotope (δ13C and δ15N) variability in aquatic plants. Freshw. Biol. 2017;62:1807–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keeley JE, Sandquist DR. Carbon: freshwater plants. Plant. Cell Environ. 1992;15:1021–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendonça R, et al. Bimodality in stable isotope composition facilitates the tracing of carbon transfer from macrophytes to higher trophic levels. Hydrobiologia. 2013;710:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long ES, Sweitzer RA, Diefenbach DR, Ben-David M. Controlling for anthropogenically induced atmospheric variation in stable carbon isotope studies. Oecologia. 2005;146:148–156. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee KY, Graham L, Spooner DE, Xenopoulos MA. Tracing anthropogenic inputs in stream foods webs with stable carbon and nitrogen isotope systematics along an agricultural gradient. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tahmasebi, F., Longstaffe, F. J. & Zazula, G. Nitrogen isotopes suggest a change in nitrogen dynamics between the late Pleistocene and modern time in Yukon, Canada. PLoS One 13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Tahmasebi, F., Longstaffe, F. J., Zazula, G. & Bennett, B. Nitrogen and carbon isotopic dynamics of subarctic soils and plants in southern Yukon Territory and its implications for paleoecological and paleodietary studies. PLoS One 12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Newsom, L. A. & Mihlbachler, M. C. Mastodons (Mammut americanum) diet foraging patterns based on analysis of dung deposits, In First Floridians Last Mastodons Page-Ladson Site Aucilla River 263–331. (Springer, Dordrecht, 2006).

- 49.Zazula GD, et al. American mastodon extirpation in the Arctic and Subarctic predates human colonization and terminal Pleistocene climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:18460–18465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416072111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.France CAM, Zelanko PM, Kaufman AJ, Holtz TR. Carbon and nitrogen isotopic analysis of Pleistocene mammals from the Saltville Quarry (Virginia, USA): Implications for trophic relationships. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007;249:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz-Narbonne R, Longstaffe FJ, Metcalfe JZ, Zazula G. Solving the woolly mammoth conundrum: Amino acid 15N-enrichment suggests a distinct forage or habitat. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–6. doi: 10.1038/srep09791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Klinken GJ. Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1999;26:687–695. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hornibrook ERC, Longstaffe FJ, Fyfe WS, Bloom Y. Carbon-isotope ratios and carbon, nitrogen and sulfur abundances in flora and soil organic matter from a temperate-zone bog and marsh. Geochem. J. 2000;34:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Milligan HE, Pretzlaw TD, Humphries MM. Stable isotope differentiation of freshwater and terrestrial vascular plants in two subarctic regions. Écoscience. 2010;17:265–275. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Russell, S. D. J. Nitrate sources in the Old Ausable River Channel and adjacent aquifers in Pinery Provincial Park. PhD dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, Department of Earth Sciences (2015).

- 56.Bateman AS, Kelly SD. Fertilizer nitrogen isotope signatures. Isotopes Environ. Health Stud. 2007;43:237–247. doi: 10.1080/10256010701550732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Government of Canada. Statistics Canada, https://www.statcan.gc.ca (2018).

- 58.Berti AA. Paleobotany of Wisconsinan interstadials, eastern Great Lakes region, North America. Quat. Res. 1975;5:591–619. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zazula GD, Froese DG, Westgate JA, La Farge C, Mathewes RW. Paleoecology of Beringian ‘packrat’ middens from central Yukon Territory, Canada. Quat. Res. 2005;63:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zazula GD, Froese DG, Elias SA, Kuzmina S, Mathewes RW. Arctic ground squirrels of the mammoth-steppe: paleoecology of Late Pleistocene middens (∼24 000-29 450 14C yr BP), Yukon Territory, Canada. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2007;26:979–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Busher PE. Food Caching Behavior of Beavers (Castor canadensis): Selection and use of woody species. Am. Midl. Nat. 1996;135:343. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muller-Schwarze, D. The beaver: its life and impact. (Cornell University Press, 2011).

- 63.Milligan HE, Humphries MM. The importance of aquatic vegetation in beaver diets and the seasonal and habitat specificity of aquatic-terrestrial ecosystem linkages in a subarctic environment. Oikos. 2010;119:1877–1886. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Severud WJ, Windels SK, Belant JL, Bruggink JG. The role of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) Mamm. Biol. 2013;78:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boulanger MT, Lattanzi GD, Parris DC, O’Brien MJ, Lyman RL. AMS radiocarbon dates for Pleistocene fauna from the American Northeast. Radiocarbon. 2015;57:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 66.McDonald, H. G. & Glotzhober, R. C. New radiocarbon dates for the giant beaver, Castoroides ohioensis (Rodentia, Castoridae), from Ohio and its extinction. In Unlocking the Unknown; Papers Honoring Dr. Richard Zakrzewski 51–59 (2008).

- 67.Collins MJ, et al. The survival of organic matter in bone: A review. Archaeometry. 2002;3:383–394. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keeling, R. F., Walker, S. J., Piper, S. C., & Bollenbacher, A. F. Scripps CO2 Program. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, http://scrippsco2.ucsd.edu. (2014).

- 69.Schmitt J, et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science. 2012;336:711–714. doi: 10.1126/science.1217161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1978;42:495–506. [Google Scholar]

- 71.DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1981;44:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Froehle AW, Kellner CM, Schoeninger MJ. FOCUS: Effect of diet and protein source on carbon stable isotope ratios in collagen: follow up to. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009;37:2662–2670. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campbell KL, MacArthur RA. Seasonal changes in gut mass, forage digestibility, and nutrient selection of wild muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus) Physiol. Zool. 1996;69:1215–1231. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Danell K. Reduction of aquatic vegetation following the colonization of a northern Swedish lake by the muskrat, Ondatra zibethica. Oecologia. 1979;38:101–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00347828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.France, C. A. M. A carbon and nitrogen isotopic analysis of Pleistocene food webs in North America: implications for paleoecology and extinction. PhD dissertation, University of Maryland, Department of Geology (2008).

- 76.Rinaldi, C., Martin, L., Cole, T. III. & Timm, R. Occlusal wear morphology of giant beaver (Castoroides) lower incisors: functional and phylogenetic implications. In Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology (2009).

- 77.Morgan GS, White JA. Small mammals (Insectivora, Lagomorpha, and Rodentia) from the early Pleistocene (Irvingtonian) Leisey Shell Pit Local Fauna, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bull. Florida Museum. Nat. Hist. 1995;37:397–461. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parmalee, P. W. & Graham, R. W. Additional records of the giant beaver, Castoroides, from the Mid-South: Alabama, Tennessee, and South Carolina. Smithson. Contrib. to Paleobiol. 93 (2002).

- 79.Hulbert R, Kerner A, Morgan GS. Taxomony of the Pleistocene giant beaver Castoroides (Rodentia: Castoridae) from the southeastern United States. Bull. Florida Mus. Nat. Hist. 2014;53:26–43. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Graham, R. W. FAUNMAP: a database documenting late Quaternary distributions of mammal species in the United States. Illinois State Museum 25 (1994).

- 81.Watts, W. A. B. C. S. & Hansen, B. A. P. Environments of Florida in the late Wisconsin and Holocene. In Wet site archaeology 307–323 (1988).

- 82.Watts WA. The late Quaternary vegetation history of the southeastern United States. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1980;11:387–410. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Koch PL, Hoppe KA, Webb SD. The isotopic ecology of late Pleistocene mammals in North America. Chem. Geol. 1998;152:119–138. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Woodburne, M. Upper Pliocene geology and vertebrate paleontology of part of the Meade Basin, Kansas. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters 46 (1961).

- 85.Jackson ST, et al. Vegetation and enviroment in Eastern North America during the Last Glacial Maximium. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2000;19:489–508. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jackson ST, Weng C. Late Quaternary extinction of a tree species in eastern North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:13847–13852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strong WL, Hills LV. Late-glacial and Holocene palaeovegetation zonal reconstruction for central and north-central North America. J. Biogeogr. 2005;32:1043–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Harington CR. Pleistocene vertebrates of the Yukon Territory. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2011;30:2341–2354. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Froese D, et al. Fossil and genomic evidence constrains the timing of bison arrival in North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:3457–3462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620754114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zazula GD, Froese DG, Elias SA, Kuzmina S, Mathewes RW. Early Wisconsinan (MIS 4) Arctic ground squirrel middens and a squirrel-eye-view of the mammoth-steppe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2011;30:2220–2237. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zazula GD, et al. A case of early Wisconsinan “over-chill”: New radiocarbon evidence for early extirpation of western camel (Camelops hesternus) in eastern Beringia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2017;171:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacobson GL, Jr., Webb T, III., Grimm EC. Patterns and rates of vegetation change during the deglaciation of eastern North America. North Am. and Adjac. Ocean. Dur. Last Deglaciation. 1987;K-3:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beaumont W, Beverly R, Southon J, Taylor RE. Bone preparation at the KCCAMS Laboratory. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. 2010;268:906–909. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Longin R. New method of collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating. Nature. 1971;230:241–242. doi: 10.1038/230241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Severud WJ, Belant JL, Windels SK, Bruggink JG. Seasonal Variation in Assimilated Diets of American Beavers. Am. Midl. Nat. 2013;169:30–42. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Steadman DW, Stafford TW, Funk RE. Nonassociation of Paleoindians with AMS-dated late Pleistocene mammals from the Dutchess Quarry Caves, New York. Quat. Res. 1997;47:105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Feranec RS, Kozlowski AL. AMS radiocarbon dates from Pleistocene and Holocene mammals housed in the New York State Museum, Albany, New York, USA. Radiocarbon. 2010;52:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Erickson BR. Paleontological evidence concerning some post glacial features of the Mississippi River Valley. Sci. Pub. Sci. Mus. 1967;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tankersley KB, Landefeld CS. Curr. Res. Pleist. 1998. Geochronology of the Sheriden Cave, Ohio: The 1997 Field Season; pp. 136–138. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare no limitations on data or standard operating protocol availability.