Abstract

Despite growing concerns for the mental health of the older generation most studies focus on mental health care for younger people and there is a lack of knowledge about helpful treatment approaches and models of care for older people. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to answer the question what health care approaches are most helpful for older people experiencing mental health problems. Databases from 2000 to July 2017 were searched with focus on outcome studies, experts’ opinions and treatment descriptions. Critical interpretive synthesis was used to analyse and interpret the findings. Four main models of care were found: the medical-psychiatric model which mostly focuses on antipsychotic medication for the treatment of symptoms. Psychotherapeutic and social interventions take into consideration the psychosocial perspectives of mental health problems, but little research has been done on their lasting effect. Research indicates that psychotherapy needs to be adapted to the special needs of older people. Few old people have access to psychotherapy which limits its usefulness. Holistic or integrated models of health care have emerged in recent years. These models focus on both physical and psychosocial well-being and have shown promising outcomes. To reduce antipsychotic medication older people need to be given better access to psychotherapy and social interventions. This presupposes training health care professionals in such treatment methods. The holistic models need to be developed and studied further and given high priority in health care policy.

Keywords: Mental health care, Quality assurance, Successful ageing, Critical interpretive synthesis

Introduction

When more years are added to a person’s life, there are more losses of close friends and family members. Also, with older age come changes in functional abilities that one needs to adjust to both physically and mentally. Hence, the growing life expectancies in the developed economies have led to growing concerns about the mental health of older people. As early as 1999, scholars in the field of geriatric psychiatry anticipated that in the near future, at least 20% of people in the USA older than 65 would suffer from mental health problems that require care (Jeste et al. 1999). A cross-national European study, involving six countries, showed that 15.2% of older people (65 +) had symptoms of subthreshold depression and 12.6% of depressive disorder (Braam et al. 2014). An American study using nationally representative data showed that 13.8% of older people (55 +) met the criterion for subsyndromal depression and 13.7% for depressive disorder (Laborde-Lahoz et al. 2015). According to Luppa et al. (2012), the prevalence of depression is even higher in latest life (75 +). They concluded from their meta-analysis that pooled prevalence of major depression was 7.2% in this age group and 17.1% for depressive disorders. Symptoms of anxiety are even more prevalent, and they are most often comorbid with symptoms of depression (Braam et al. 2014).

Numerous studies show that mental health problems diminish the quality of life of older people. For example, Unützer et al. (2000) found that primary care patients older than 65 and suffering from depression experience much lower quality of life than non-depressed persons, and several studies (e.g. Brown et al. 2011; Djernes et al. 2011) have found that depressed older people had higher mortality rate. Also studies have shown that the prognosis for depression amongst older patients in primary care is poorer than amongst younger patients (e.g. Licht-Strunk et al. 2009). Therefore, there is a general consensus that there is an urgent need to develop specialized services for older people with mental health problems (Aakhus et al. 2012; Bartels et al. 2003). When developing such services the barriers that hinder older people from seeking mental health care need to be considered (Mackenzie et al. 2010), including lack of health care professionals with adequate mental health training (Beck et al. 2011).

Anxiety and depression are the most common mental health problems associated with older people’s declining physical health. Two reviews found that 20–50% of older people with physical health problems suffer from depressive symptoms (Djernes 2006; Egede 2005). Also, research has shown that depressive symptoms are more strongly related to functional disability, and difficulties in performing activities of daily living, than with physical conditions alone (Braam et al. 2005; Meltzer et al. 2012). The few studies that have focused on the care needs of older people with depression, also, indicate a relationship between functional disability and depression. Houtjes et al. (2010) and Stein et al. (2016) found that unmet needs associated with daytime activities were related to depression amongst older people. Houtjes et al. (2010) also found that depression severity was related to unmet care needs in eyesight and hearing. Furthermore, late-life depression is associated with poor socio-economic status and social isolation (Copeland et al. 2004). Depression and anxiety are much more prevalent amongst older people living in an institutional setting than in private households (Djernes 2006; Seitz et al. 2010). This high prevalence of depression amongst older people in institutional care is of great concern for healthcare professionals.

When planning and developing mental health services for older people, policymakers and health professionals need to ask: What practical and theoretical approaches are most likely to enhance quality of life? In other words, what models of mental health care have the best potential to improve the quality of life of older people suffering from mental health problems? Until recently the development of mental health care systems has been targeted to the needs of young and middle-aged people. Hence, models of mental health care are mostly drawn from research on the needs of those who have not reached the retirement age. Studies on the care needs of older people show that those suffering from depression have more unmet needs than their non-depressive counterparts and that the severity of the depression is strongly related to unmet needs (Houtjes et al. 2010; Stein et al. 2016). Houtjes et al. (2012) also showed that meeting these needs can lead to better treatment results. Due to changes in social functioning, cognition and physiology, it cannot be assumed that mental health interventions, that have shown good results for younger people, will also be helpful for older people (Bartels et al. 2003; Ng 2018; Voyer and Martin 2003). The same argument applies to models of mental health care, and little is known about whether these interventions and models have successfully been, or have the potential to be, adjusted to the needs of older people. Therefore, the aim of this review is to answer to the question: Which models of care are helpful for older people experiencing mental health problems?

Numerous reviews and meta-analysis have been performed on the effectiveness of psychotropic medication and psychotherapeutic interventions for older people experiencing mental health problems. For example, the Pinquart’s and Sörensen (2001) hallmark study showed that psychotherapy with older people “… promotes an improvement in depression and increases general psychological well-being” (p. 230) and that psychosocial interventions enhance their subjective well-being. Therefore, the purpose of the current critical review was not to find out which models of care are most effective, measured with specific outcome indicators, but to assess their helpfulness according to broader criteria described below. Our aim was to summarize theoretical and empirical literature to gain a broad understanding of how different models of care meet the mental health needs of older people. Accordingly, a qualitative review method (critical interpretive synthesis) was used to answer the research question.

The assessment of helpfulness

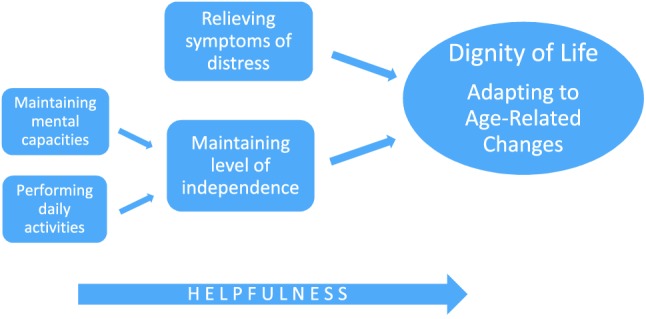

Before the helpfulness of mental health care can be assessed we need to answer the question: What are the desired outcomes of care for older people experiencing mental health problems? When searching the literature for “principles of good mental health care for older people” we found that the concept of dignity of life captures helpful adaptations to changes in the quality of life that both precede and follow mental health problems amongst older people, such as decreased functional abilities and losses in social contacts (Blanchard et al. 2009; Gibson et al. 2010).

Dignity of life is seen as a crucial component of older people’s quality of life for two reasons: firstly, because people become more vulnerable and dependent on others as they become older and, secondly, because dignity in dying is of great concern for those caring for older people and the terminally ill. Hence, some of the most important studies concerned with personal dignity originate from cancer care (Chochinova et al. 2002). The concept of dignity is hard to operationalize for the purpose of empirical studies. Therefore, scholars in the field of geriatric care have focused on factors that are believed to enhance people’s sense of dignity. It is a general consensus that autonomy and integrity are the most important of these factors (Franklin et al. 2006; Gibson et al. 2010; Randers and Mattiasson 2004). Autonomy is understood as the ability to make choices and to take responsibility for one’s own life and integrity as the ability to maintain privacy and personal space.

Chochinova et al. (2002) offer an insight into threats to dignity that can be used when assessing whether health care succeeds in maintaining or increasing the dignity of older people experiencing mental health problems. One of the categories that emerged from their study was illness-related concerns that influence dignity with the subthemes: level of independence and symptom distress. Symptom distress refers to physical and psychological distress caused by an illness that diminishes people’s ability to keep their sense of dignity. These findings are supported by Houtjes et al. (2010), who found that “most of the unique variances in depression severity [among 58–92 year old outpatients with depression] was explained by psychological unmet needs… presenting psychological distress” (p. 874). It is self-evident that mental health care is helpful if it manages to diminish symptoms of mental health illnesses. Level of independence, according to Chochinova et al. (2002), has two dimensions: “… the ability to maintain one’s mental/thinking capacity” (p. 435) and “… the ability to perform tasks associated with activities of daily living” (p. 436). Being able to maintain one’s mental capacity and to perform activities of daily living are preconditions for maintaining autonomy and integrity. Decreases in functional abilities and losses in social contacts precede and follow declining mental health amongst older people (Blanchard et al. 2009; Gibson et al. 2010). Therefore, helpful mental health care would promote adaptation to these conditions. Accordingly, Blanchard et al. (2009) have proposed that psychosocial support for older people should include “help to guide the grieving of the losses and significant changes” (p. 205) and “helping people to accept any new limitations placed upon them and to explore different directions” (p. 206). Therefore, we assume that mental health care is helpful if it promotes dignity of life and adaption to age-associated changes. To meet these goals mental health care needs to meet the criteria of relieving symptoms of distress and assisting older people to maintain their level of independence by helping them to maintain mental capacities and perform daily activities. The picture below shows how the criteria for helpful mental health care for older people are related (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Criteria for helpful mental health care for older people

Method

Critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) as described by Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) was chosen as a method for this review. We also sought guidance from Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) description of integrative review methods. CIS is better suited than traditional review methods when the answer to the research question can only be approached by reviewing different types of evidence and when the aim is to develop theories (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006). CIS does not require the reviewer to start out with a narrow research question or a hypothesis. Instead, it allows us to modify “… the question in response to search results findings from retrieved items” (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006, p. 3). In this review it was not suitable to formulate a narrow research question because we wanted to let clarifications of concepts emerge from the findings. We wanted to identify the models of care into which different approaches to older people’s mental health care could be categorized and to clarify the concept of helpfulness so it could be used as a criterion for the assessment of these models.

Whittemore and Knafl (2005) describe five stages of integrative reviews that were adopted for the purpose of the study. The problem identification stage applies to our initial concerns about the growing mental health needs of older people and about the importance of clarifying how well these needs are met. We wanted to draw as broad a picture as possible. Hence, we were not only interested in the outcome of particular interventions, but also in older people’s barriers to interventions and expert opinions. Also, we were interested in descriptions of mental health care programmes to be able to assess if, and how, they address the complex mental health needs of older people.

The second stage, the literature search, was guided by the broad scope of the problem identification stage; we began the search by combining the keyword of mental health, mental health care, mental health services, psychiatric nursing and psychotherapy with geriatric psychiatry, retirement, aged/ageing and geriatrics. The search results were used to identify references that helped to gain the goals defined in the problem identification stage. Based on these findings we narrowed our search strategies. The electronic databases, Web of Science, MEDLINE and PubMed were searched, and the search was limited to the years 2000 to July 2017. Cross-referrals were also used.

The third stage, data evaluation, was combined with the literature search stage as described above. The search yielded 270 articles, but 93 articles were excluded based on the abstract. The remaining 177 full articles were reviewed. Of these 94 were excluded because they did not serve the purpose of clarifying the concepts in the research question or of answering it, or did not meet the quality criteria, which are described below. The remaining 83 articles fall roughly into six categories. (1) Outcome studies (n = 23) on the effectiveness of interventions and models of care. Only meta-analyses and systematic reviews were included, except for studies on the outcomes of holistic or integrated models since such analyses and reviews were lacking. (2) Epidemiological and prevalence studies on mental health problems, psychotropic medication, service needs and access to health care (n = 17). International and nationwide studies and systematic reviews were included. (3) Studies on the relationships between mental health problems and indicators of quality of life, such as physical health, social engagement and use of care (n = 8). Longitudinal studies and/or studies from nationwide samples were included. (4) Studies on the predictors, consequences and prognoses of mental health problems (n = 8). Systematic reviews, longitudinal studies and studies from national surveys were included. (5) Articles on policymaking and clinical guidelines and articles proposing new approaches to interventions and models of care (n = 17). Editorials in internationally recognized scientific journals and commentaries by authors with research records on older people’s mental health and treatment. (6) Descriptive articles and research (n = 10). This refers to articles that described models of care and qualitative studies on the views and experiences of older people and mental health workers. These kinds of references are rare, but have strong relevance to the research question. Therefore, all articles that were found were included.

The fourth stage, data analyses, had two intertwined phases: first, to define the concept of helpfulness and identify models of mental health care and, second, to assess how well each model met the criterion of helpfulness. In the assessment, references regarding each identified model of care were searched for evidence for if and how well they met the helpfulness criterion. This evidence was then synthesized to give an overall picture of the models and how they met the criterion. The results of the last stage, presentation, appear in the next two chapters.

Results

The findings of this critical interpretive synthesis indicate that models of mental health care for older people can be divided into three groups based on the understanding of mental health problems on which their interventions are based: (1) the medical-psychiatric model, (2) psychosocial interventions and (3) the holistic or integrated models of care. Most studies of the first two models focus on a single type of intervention, such as medication or psychotherapy, whilst studies of the holistic models focus on the overall quality of life. Authors addressing specific interventions usually do not address the theoretical perspectives on which the interventions are built. They are mostly pragmatic in their approach, asking questions about treatment outcomes.

The medical-psychiatric model

The medical-psychiatric model is based on the understanding that mental health problems are due to pathophysiological processes and hence, relies on psychotropic medication for treatment, treatment which is indeed the most common intervention for older people experiencing mental health problems. Already in 1996, 19% of the community-dwelling older people in the USA used psychotropic medication (Aparasu et al. 2003). Several studies show that the prevalence might be higher in other developed countries (e.g. Rikala et al. 2011; Téllez-Lapeira et al. 2016) and also that the use of psychotropic medication is increasing (Carrasco-Garrido et al. 2013; Ndukwe et al. 2014; Maust et al. 2017). Psychotropic medication is more prevalent amongst nursing home residents than amongst older people who live in the community. Stevenson et al. (2010) found that 26% of nursing home residents in the USA were prescribed antipsychotic medication, and studies indicate a higher prevalence in Europe; for example, Richter et al. (2011) found that 74.6% of nursing home residents in Austria and 51.8% in Germany were prescribed psychotropic medication, and Lövheim et al. (2008) found that the use of antidepressants had increased from 6.3% to 39.9% and tranquilizers from 13.25% to 39.9% between 1982 and 2000, amongst older people living in Swedish nursing homes.

Leading scholars in the field of psychiatry have pointed out that due to age-related changes in physiology and cognition, psychotropic medicines are likely to have a different effect on older people than on young people (Bartels et al. 2003). Furthermore, most of the research evidence, on which prescriptions of psychotropic medicine are based, are drawn from studies on younger people. For example, Wilkinson and Izmeth (2016) concluded from their updated meta-analysis that 12 months of continuous antidepressant medication appears to be helpful, though with the condition that it was based on only three small studies. They also found that the long-term benefits of continuing antidepressant medication for older people are unclear and that “… no firm treatment recommendations can be made on the basis of this review” (p. 2) and also, that the quality of the research included in the review was low. The increased risk of side effects due to declining functional status, and polypharmacy, which is often not duly considered when psychotropic medicine are prescribed to older people, add to the uncertain benefits of psychotropic medicine (Maust et al. 2014; Vidal et al. 2016). Studies indicate that psychotropic medication for older people is more effective if it is combined with psychological treatment (Clarke et al. 2015; Mackin and Areán 2005). This is more evident when mental health problems are related to psychosocial stressors (Bartels et al. 2003). However, few studies take into account how age-related psychosocial stressors and social support influence the prognoses of mental health problems (Mitchell and Subramaniam 2005). Also, studies have shown that older people diagnosed with depression or anxiety prefer counselling and psychotherapy rather than medication (Gum et al. 2006; Luck-Sikorski et al. 2017; Mohlman 2012). Nevertheless, Sanglier et al. (2015) found by matching 6316 depressed older people (65 +) with 25,264 depressed adults, younger than 65, from an national US database that the older people were almost three times less likely to receive psychotherapy (13.0% vs. 34.4%). The older people were also less likely to be treated with antidepressants (25.6% vs. 33.8%).

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial interventions can be defined as interventions aimed at the psychological and social cause and manifestation of mental suffering rather than on the biological factors like the medical-psychiatric model. Most often these approaches to care use clearly defined and time-limited interventions with the purpose of improving psychological and/or social well-being.

Psychotherapeutic interventions

In accordance with the psychological theories on which psychotherapeutic interventions are based, they do not only focus on the symptoms of mental suffering, but also on the psychosocial stressors and life events that caused it. Most research evidence has been gathered on the positive outcome of problem-solving therapy (PST) and other forms of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for depression and anxiety in older people (Francis and Kumar 2013; Holvast et al. 2017; Jonsson et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2008). However, Cuijpers et al. (2011) concluded from a series of meta-analysis that different types of psychotherapies gave similar results for the treatment of late-life depression. The findings of Cuijpers et al. are supported by the few studies that have compared CBT with other types of psychotherapies for older people. These studies did not find any significant difference in treatment outcome between CBT and psychodynamic therapies (Mackin and Areán 2005; Wilson et al. 2008). Research has shown positive results for variety of psychotherapeutic interventions, e.g. problem-solving therapy, reminiscence therapy, brief psychodynamic therapy (Francis and Kumar 2013; Holvast et al. 2017; Huang et al. 2015), interpersonal psychotherapy (Francis and Kumar 2013; Huang et al. 2015) and bibliotherapy (Holvast et al. 2017). Also, the review by Ayers et al. (2007) showed the positive outcomes of relaxation training for older people suffering from anxiety. The outcome studies included in the meta-analysis and systematic reviews referred to above, with few exceptions, measure treatment outcomes with scores on symptom scales. After conducting their systematic review, Wilson et al. (2008) concluded that “outcomes measures should be broader than just scores on depression rating scales” (p. 11). Therefore, it is difficult to assess if the positive outcomes measured in these studies apply to the indicators of helpfulness set in this review, except for symptoms of distress. However, some of the items in the most widely used scales, for example, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, measure levels of daily functioning which are indicators of the level of independence, the capacity of performing daily activities. The same applies to the few studies that have been done on the effectiveness of psychotropic medication for older people.

Even though it is generally agreed that the outcome of psychotherapeutic interventions for older and younger people is comparable (Choi 2009; Cuijpers 2017), scholars in the field of geropsychology emphasize the importance of adjusting psychological interventions to the needs of older people, for example, by slowing the intervention pace, due to the slower cognitive function following older age (Bartels et al. 2003; Mackin and Areán 2005). This notion is supported by research that shows that psychotherapy for older people is more successful if the therapist has a special training in working with older people (Pinquart and Sörensen 2001).

Social interventions

Social isolation caused by the loss of loved ones and changes in social roles is one of the main risk factors for mental health problems amongst older people. Also, reduced social activity and a smaller social network have been shown to have a strong relation with depression amongst older people (Schwarzbach et al. 2014), whilst increased social activity has been shown to have the opposite effect (Hajek et al. 2017). Because there are few longitudinal studies it is hard to conclude if social isolation causes depression, if those who become depressed withdraw from social activity, or if there is an interactive relationship between these factors. However, Glass et al. (2006) concluded from longitudinal data that a decline in social engagement predisposes depressive symptoms amongst older people and Forsman et al. (2011) found that increased social activity reduced depressive symptoms. On the other hand, Houtjes et al. (2014) found that the course of chronic depression decreases social network size and concluded from their study that “… these effects may lead into further depression, creating a vicious cycle that undermines social embeddedness and leading to social isolation…” (p. 1016). There are a wide range of interventions that fall into the category of social interventions such as social skills training, social support groups and a physical exercise programme. The outcome of such interventions for older people experiencing mental health problems is not as well studied as the outcome of psychotherapeutic interventions. On the other hand, many studies have been done on the preventive effect of social interventions for older people in general and older people suffering from physical illnesses (Forsman et al. 2011). The physical exercise interventions for depressed older people, whose outcome has been studied, have a social engagement factor associated within them. Catalan-Matamoros et al. (2016) and Holvast et al. (2017) found that such interventions reduced depressive symptoms amongst older participants. It is noteworthy that two of the studies reviewed by Holvast et al. (2017) observed no difference between exercise groups and control groups who got interventions with social aspect to them: social contact control and cognitive behavioural group therapy.

Holistic or integrated models

To respond to the somewhat narrow scopes and sometimes poor outcomes of the medical-psychiatric and psychosocial models, numerous integrative or holistic models of care for older people experiencing mental health problems have been proposed and implemented. These models are based on the belief that mental health problems are caused by interactive physiological, psychological and social factors. For decades it has been presumed that the best mental health care for older people—and other age groups for that matter—needs to be comprehensive, multidisciplinary, accessible and integrated with other health and social services (Bartels et al. 2002; Jolley and Arie 1978). The most comprehensive of these models address medical, psychological and social issues and involve numerous clinicians from different disciplines, such as psychiatry, mental health nursing, social work and psychology (McEvoy and Barnes 2007; Moak 2011).

Nursing homes

The holistic ideals do not only apply to mental health care, but have guided what is sometimes called the culture-change movement in nursing home care. This movement strives to deinstitutionalize the nursing home culture and create instead homelike nursing homes with person-centred care (Koren 2010; Zimmerman et al. 2014). These models of care, for example the Eden Alternative Model and the Green House Model, are not especially directed towards mental health, but strive to address the “… psychosocial problems of residents, such as loneliness, boredom, helplessness and lack of meaning” (Kane et al. 2007, p. 832).

Three reviews were found that deal with the question of whether the culture-change movement has improved quality of nursing home care (Grabowski et al. 2014; Shier et al. 2014; Zimmerman et al. 2016). These reviews did not find conclusive evidence of improved quality of care or positive resident outcome in culture-change homes compared with conventional nursing homes. However, one longitudinal quasi-experimental study (Kane et al. 2007) found that Green House residents experienced better quality of life in several areas. Amongst them are dignity and autonomy, which correspond to the helpfulness criteria of “dignity of life” and “maintaining level of independence”, and relationship which corresponds to the criterion “adapting to age-related changes” because losses in social contacts are one of the most significant changes that comes with older age. The reviews from 2014 (Grabowski et al. 2014; Shier et al. 2014) did not focus on mental health indicators. On the other hand, Zimmerman et al. (2016) found studies showing that the adoption of Green House nursing homes increased both the residents’ social engagement and depressive symptoms, with the explanation that the reason might be more attentive staff and at the same time better reporting of depressive symptoms. An alternative explanation of the increase in depression is that the fundamental life changes older people go through when moving to a nursing home might in itself be depressing (Smalbrugge et al. 2006). This lack of positive findings from culture-change nursing homes might be due to the generally held opinion “… that the quality of care provided in LTC [long-term care facilities] is highly dependent upon the knowledge, skills and quality of intervention provided by those working as direct caregivers” (Gibson et al. 2010, p. 1076). These studies did not assess the standard of care. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn from whether the success of the culture-change movement might depend on how successfully its principles are put into practice.

Community care

It is premature to talk about a culture change in the care of older people in the community settings. However, several holistic or integrated models of mental health care for older people have been proposed and implemented with good results. Most of these models have in common the ideas of multidisciplinary teams and care management to ensure that the service users can benefit from best available services (McEvoy and Barnes 2007; Moak 2011).

Many of these models, e.g. the depression care management model (DCM), draw from “chronic care models” for treating chronic diseases. DCM is defined as a systematic multidisciplinary team approach and was strongly recommended by an expert panel of researchers and practitioners after thorough review of the relevant literature (Snowden et al. 2008). An example of a successful implementation of a DCM is the Program to Encourage Active, Rewarding Lives of Seniors (PEARLS) that was aimed at low-income older people with minor depression or dysthymia. The project that consisted of problem-solving treatment, social and physical activity and referral to clinicians if needed, has been shown to be helpful, by assisting older people in maintaining level of independence by enhancing their mental capacity, performing daily activities and social engagement (Ciechanowski et al. 2004).

The idea that mental health care for older people can learn from chronic care models is based on the notion that such models are developed as a response to modern medicine’s narrow focus on acute and episodic illnesses (McEvoy and Barnes 2007). Wagner et al. (2002) proposed a collaborative chronic care model (CCM) that has been adapted to mental health care for older people. This model is comprehensive and, along with a multidisciplinary approach and care management, includes the factors necessary to give holistic care and empower the service users, such as support for self-help, clients’ active engagement in service management and strong links with resources in the community. Alongside PEARLS, other mental health care programmes for older people whose interventions were inspired by chronic care models have been shown to be helpful by helping participants in maintaining mental capacity and performing daily activities. For example, the Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Care Treatment (IMPACT) programme, which was aimed at older people with major depression and/or dysthymic disorder (Hunkeler et al. 2006). These findings are supported by other research findings that show that collaborative chronic care models give a better outcome than conventional mental health care regardless of the age group (Miller et al. 2013). Also, collaborative mental health care for older people has been shown to be less costly than usual care (Unützer et al. 2008).

How do the models of care meet the criterion of helpfulness?

The main focus of the medical-psychiatric approach is to relieve symptoms of mental health suffering, which is essential first step in meeting the helpfulness criterion of performing daily activities and maintaining mental capacity. The model relies on medication in order to reduce symptoms amongst older people, but evidence for such effect is mostly lacking (Wilkinson and Izmeth 2016). Therefore, it cannot be concluded that the medical-psychiatric model meets our helpfulness criterion. The model would have more success meeting this criterion if psychiatric medication was combined with psychotherapy, as research has shown that such a combination is more successful in reducing symptoms than medication alone (Clarke et al. 2015; Mackin and Areán 2005).

Contrary to the medical-psychiatric model, psychosocial interventions do not ignore age-associated changes that often cause older people’s mental health problems. However, it is hard to tell how successful they are in helping older people adapt to these changes because the indicators most often used to measure their outcomes do not reflect them (Wilson et al. 2008). From numerous outcome studies it can, however, be concluded that these interventions do, in many cases, relieve symptoms of mental health problems, which partly meet the criterion of relieving symptoms of distress a step towards meeting the criteria of maintaining mental capacity and performing daily activities.

According to the theoretical principles on which they are based (see, for example, Hollon and Beck 1994) psychotherapeutic interventions do not only strive to relieve symptoms, but also to help the client make lasting changes in their lives that will sustain the positive gains of the interventions. If the interventions succeed in this, it can be assumed that they meet the criteria of helping older people maintain a level of independence and hence, adapt to age-related changes. Also, because of the strong relation between social activity and depression amongst older people (Schwarzbach et al. 2014; Hajek et al. 2017), it can be expected that interventions that aim at breaking social isolation meet that criteria. However, evidence for the longer-term efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions is lacking (Clarke et al. 2015) and studies on the outcome of social interventions are few. Therefore, few claims can be made about their lasting effects. Furthermore, the studies that measure the outcome of psychosocial interventions have the same shortcomings as studies of the medical-psychiatric model. They only measure changes in disease symptoms, but ignore factors associated with life age-related changes and level of independence.

The two main currents in holistic care for older people, the culture-change movement in nursing homes and collaborative community care, show promising potentials in meeting the shortcoming of the medical-psychiatric and psychosocial models of care. When reviewing the outcome studies referred to above that did not show better outcomes for nursing homes in the culture-change movement, one needs to keep in mind that these studies were not especially focused on mental health indicators nor on the indicators for dignity of life and adapting to age-related changes proposed in this review. It should be pointed out that one study that compared four Green House nursing homes (N = 40) with usual homes found higher self-reported emotional well-being and few symptoms of depression amongst the Green House residents even though no difference was found in self-reported general health (Kane et al. 2007). The collaborative care models have been shown to meet many of the criteria of helpful mental health care for older people proposed in this review. The outcome studies that assessed their successfulness did not only examine illness symptoms, but also indicators for independence and abilities to perform daily activities such as physical functioning and quality of life. The collaborative models are still in the experimental stage, but enough positive evidence has been gathered to urge health authorities and professionals to apply them to general community care.

Discussion

The medical-psychiatric model is the dominant model of mental health care for older people. Not only physicians but also nurses working in nursing homes and community care for older people are oriented towards it (Ryan et al. 2006; Voyer and Martin 2003). By focusing solely on symptoms, and by ignoring the normal life changes that often cause them, the model sustains the dominant “… culture where the ageing process… is increasingly regarded as ‘pathological’ [and] seen in terms of clinical events whose management involves the use of rapidly developing medications and other technologies” (Blanchard et al. 2009, p. 202). For the medical-psychiatric model to meet the criteria of helping older people maintain level of independence and adapt to age-related changes it needs to focus not only on the pathophysiology and symptoms of mental suffering, but also on the age-related stressors that cause it, such as losses and changes in functional abilities.

The holistic and integrated model of care has the potential to meet the helpfulness criterion defined in this review. Research has already shown promising outcomes of this model in community care, but the culture-change movement in nursing home care needs to be studied further. The objectives of the movement are, amongst others, to maintain their residents’ level of independence and help them to adapt to age-associated changes by addressing problems like loneliness, boredom and lack of meaning. The means and efforts taken to meet these objectives vary between nursing homes which might explain the differences in outcomes of care. In spite of the promises of the holistic and integrated model one can expect that for the years to come, most older people will still get mental health support from interventions grounded in the medical-psychiatric and psychosocial models of care. Therefore, it is of great importance that these models adjust to the special needs of older people. It is also essential that these models work better together, as psychotropic medication is more effective when combined with psychosocial interventions. Also, until holistic models of care are fully established, older people need better access to psychosocial interventions to turn around the almost epidemic increase in prescriptions of psychotropic medicine especially in nursing homes. To meet that goal the barriers that hinder older people’s access to psychosocial interventions need to be addressed. For example, some older people might lack the social support and the information that could motivate them to take advantage of psychosocial interventions (Choi 2009; Karlin et al. 2008) and most health care providers who older people come in contact with lack the skills necessary for delivering such interventions (Gonçalves et al. 2014; Knight 2011). To overcome these barriers several authors have proposed that those who provide health care for older people, such as home visits, community-based services and nursing home care, will be educated and trained to deliver psychosocial interventions (Choi 2009; Voyer and Martin 2003).

The medical-psychiatric and psychosocial models of care are based on the assumptions that people can overcome mental health problems by consuming psychotropic medicine or by participating in structured and time-limited intervention led by a qualified helper. These assumptions have been contradicted by new concepts of care emphasizing a more active role of the mental health care service user in their treatment and recovery—it is noteworthy that in our review of the literature the concept of recovery model only occurred once (Blanchard et al. 2009). The essence of the recovery model is that people take matters into their own hands and are in control of their lives and health in accordance with their abilities and their degree of dependence. Therefore, the recovery model approach could be helpful in meeting the shortcomings of medical and psychosocial interventions. Anthony (1993) defined recovery as “a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with the limitations caused by illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness” (p. 15). This definition could be adapted to the mental health needs of older people by changing the latter sentence into: Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the age-related stressors that lead to mental health suffering, such as losses, loneliness and decreased functional abilities.

Footnotes

Responsible editor: D. J. H. Deeg.

References

- Aakhus E, Flottorp SA, Oxman AD. Implementing evidence-based guidelines for managing depression in elderly patients: a Norwegian perspective. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2012;21:237–240. doi: 10.1017/S204579601200025X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Aparasu RR, Mort JR, Brandt H. Psychotropic prescription use by community-dwelling elderly in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:671–677. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers CR, Sorrell JT, Thorp SR, Wetherell JL. Evidence-based psychological treatments for late-life anxiety. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:8–17. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Moak GS, Dums AR. Models of mental health services in nursing homes: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1390–1396. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxam TE, Schneider LS, Areán PA, Alexopoulos GS, Jeste DV. Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiat Clin North Am. 2003;26:971–990. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C, Buckwalter KC, Dudzik PM, Evans LK. Filling the void in geriatric mental health: the geropsychiatric nursing collaborative as a model for change. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59:236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard M, Serfaty M, Duckett S, Flatley M. Adapting services for a changing society: a reintegrative model for old age psychiatry (based on a model proposed by Knight and Emanuel, 2007) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:202–206. doi: 10.1002/gps.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam AW, Prince MJ, Beekman AT, et al. Physical health and depressive symptoms in older Europeans: results from EURODEP. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:35–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam AW, Copeland JR, Delespaul PA, et al. Depression, subthreshold depression and comorbid anxiety symptoms in older Europeans: results from the EURODEP concerted action. J Affect Disord. 2014;155:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Stewart JC, Stump TE, Callahan CM. Risk of coronary heart disease events over 15 years among older adults with depressive symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:721–729. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181faee19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Garrido P, López de Andrés A, Hernández Barrera V, Jiménez-Trujillo I, Jiménez-García R. National trends (2003–2009) and factors related to psychotropic medication use in community-dwelling elderly population. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:328–338. doi: 10.1017/S104161021200169X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan-Matamoros D, Gomez-Conesa A, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D. Exercise improves depressive symptoms in older adults: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinova HM, Hackb T, McClementc S, Kristjanson L, Harlose M. Dignity in the terminally ill: a developing empirical model. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:433–443. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG. The integration of social and psychologic services to improve low-income homebound older adults’ access to depression treatment. Fam Community Health. 2009;32(Suppl. 1):27–35. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000342837.97982.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:1569–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K, Mayo-Wilson E, Kenny J, Pilling S. Can non-pharmacological interventions prevent relapse in adults who have recovered from depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland JRM, Beekman ATF, Braam AW, et al. Depression among older people in Europe: the EURODEP studies. World Psychiatry. 2004;3:45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P. Four decades of outcome research on psychotherapies for adult depression: an overview of a series of meta-analyses. Can Psychol. 2017;58:7–19. doi: 10.1037/cap0000096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Andersson G, Donker T, van Straten A. Psychological treatment of depression: results of a series of meta-analyses. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65:354–564. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.596570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:372–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djernes JK, Gulmann NC, Foldager L, Olesen F, Munk-Jørgensen P. 13 year follow up of morbidity, mortality and use of health services among elderly depressed patients and general elderly populations. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:654–662. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.589368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede L. Effect of comorbid chronic diseases on prevalence and odds of depression in adults with diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:46–51. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149260.82006.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman AK, Schierenbeck I, Wahlbeck K. Psychosocial interventions for the prevention of depression in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Health. 2011;23:387–416. doi: 10.1177/0898264310378041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis JL, Kumar A. Psychological treatment of late-life depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36:561–575. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin LL, Ternestedt BM, Nordenfelt L. Views on dignity of elderly nursing home residents. Nurs Ethics. 2006;13:130–146. doi: 10.1191/0969733006ne851oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MC, Carter MW, Helmes E, Edberg AK. Principles of good care for long-term care facilities. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:1072–1083. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, Mendes de Leon CF, Bassuk SS, Berkman LF. Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: longitudinal findings. J Aging Health. 2006;18:604–628. doi: 10.1177/0898264306291017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves DC, Coelho CM, Byrne GJ. The use of healthcare services for mental health problems by middle-aged and older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59:393–397. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski DC, O’Malley AJ, Afendulis CC, Caudry DJ, Elliot A, Zimmerman S. Culture change and nursing home quality of care. Gerontologist. 2014;54(Suppl. 1):35–45. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gum AM, Areán PA, Hunkeler E, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006;46:14–22. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek A, Brettschneider C, Mallon T, et al. The impact of social engagement on health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in old age–evidence from a multicenter prospective cohort study in Germany. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:140. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0715-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Beck AT. Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In: Bergin EA, Garfield SL, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. Oxford: Wiley; 1994. pp. 428–466. [Google Scholar]

- Holvast F, Massoudi B, Oude Voshaar RC, Verhaak PFM. Non-pharmacological treatment for depressed older patients in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtjes W, van Meijel B, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT. Major depressive disorder in late life: a multifocus perspective on care needs. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:874–880. doi: 10.1080/13607861003801029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtjes W, van Meijel B, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT. Late-life depression: systematic assessment of care needs as a basis for treatment. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19:274–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtjes W, van Meijel B, van de Ven PM, Deeg D, van Tilburg T, Beekman A. The impact of an unfavorable depression course on network size and loneliness in older people: a longitudinal study in the community. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:1010–1017. doi: 10.1002/gps.4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AX, Delucchi K, Dunn LB, Nelson JC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. Br Med J. 2006;332:259–263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DC, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: research agenda for the next 2 decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:848–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley DJ, Arie T. Organization of psychogeriatric services. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson U, Bertilsson Allard P, Gyllensvärd H, Söderlund A, Tham A, Andersson G. Psychological treatment of depression in people aged 65 years and over: a systematic review of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0160859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RA, Lum TY, Cutler LJ, Degenholtz HB, Yu TC. Resident outcomes in small-house nursing homes: a longitudinal evaluation of the initial green house program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:832–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, Duffy M, Gleaves DH. Patterns and predictors of mental health service use and mental illness among older and younger adults in the United States. Psychol Serv. 2008;5:275–294. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.5.3.275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M. Access to mental health care among older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2011;37:16–21. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20110201-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren MJ. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: the culture-change movement. Health Aff. 2010;29:312–317. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborde-Lahoz P, El-Gabalawy R, Kinley J, Kirwin PD, Sareen J, Pietrzak RH. Subsyndromal depression among older adults in the USA: prevalence, comorbidity, and risk for new-onset psychiatric disorders in late life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;30:677–685. doi: 10.1002/gps.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht-Strunk E, van Marwijk HW, Hoekstra T, Twisk JW, De Haan M, Beekman AT. Outcome of depression in later life in primary care: longitudinal cohort study with three years’ follow-up. BMJ. 2009;338:a3079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim H, Sandman PO, Kallin K, Karlsson S, Gustafson Y. Symptoms of mental health and psychotropic drug use among old people in geriatric care, changes between 1982 and 2000. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:289–294. doi: 10.1002/gps.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck-Sikorski C, Stein J, Heilmann K, et al. Treatment preferences for depression in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:389–398. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, et al. Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie CS, Pagura J, Sareen J. Correlates of perceived need for and use of mental health services by older adults in the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology surveys. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:1103–1115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackin RS, Areán PA. Evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions for geriatric depression. Psychiat Clin North Am. 2005;28:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust DT, Oslin DW, Marcus SC. Effect of age on the profile of psychotropic users: results from the 2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:358–364. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, Kales HC, Marcus SC. National trends in antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and other sedative-hypnotic treatment of older adults in psychiatric and primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e363–e371. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m10713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy P, Barnes P. Using the chronic care model to tackle depression among older adults who have long-term physical conditions. J Psychiatr Ment Health. 2007;14:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Brugha T, McManus S, Rai D, Dennis MS, Jenkins R. Physical ill health, disability, dependence and depression: results from the 2007 national survey of psychiatric morbidity among adults in England. Disabil Health J. 2012;5:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron BE, Kilbourne AM, Woltmann E, Bauer MS. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta-analysis and metaregression to guide future research and implementation. Med Care. 2013;51:922–930. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a3e4c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Subramaniam H. Prognosis of depression in old age compared to middle age: a systematic review of comparative studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1588–1601. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moak GS. Treatment of late-life mental disorders in primary care: we can do a better job. J Aging Soc Policy. 2011;23:274–285. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2011.579503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlman J. A community based survey of older adults’ preferences for treatment of anxiety. Psychol Aging. 2012;27:1182–1190. doi: 10.1037/a0023126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndukwe HC, Tordoff JM, Wang T, Nishtala PS. Psychotropic medicine utilization in older people in New Zealand from 2005 to 2013. Drugs Aging. 2014;31:755–768. doi: 10.1007/s40266-014-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TP. Old age depression: worse clinical course, brighter treatment prospects? Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30186-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. How effective are psychotherapeutic and other psychosocial interventions with older adults? A meta-analysis. J Ment Health Aging. 2001;7:207–243. [Google Scholar]

- Randers I, Mattiasson AC. Autonomy and integrity: upholding older adult patients’ dignity. J Adv Nur. 2004;45:63–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter T, Mann E, Meyer G, Haastert B, Köpke S. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use among German and Austrian nursing home residents: a comparison of 3 cohorts. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;13:187.e7–187.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikala M, Korhonen MJ, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Psychotropic drug use in community-dwelling elderly people-characteristics of persistent and incident users. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:731–739. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-0996-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R, Garlick R, Hapell B. Exploring the role of the mental health nurse in community mental health care for the aged. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27:91–105. doi: 10.1080/01612840500312902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanglier T, Saragoussi D, Milea D, Tournier M. Depressed older adults may be less cared for than depressed younger ones. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:905–912. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbach M, Luppa M, Forstmeier S, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Social relations and depression in late life-a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:1–21. doi: 10.1002/gps.3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:1025–1039. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shier V, Khodyakov D, Cohen LW, Zimmerman S, Saliba D. What does the evidence really say about culture change in nursing homes? Gerontologist. 2014;54:S6–S16. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalbrugge M, Jongenelis L, Pot AM, Eefsting JA, Ribbe MW, Beekman AT. Incidence and outcome of depressive symptoms in nursing home patients in the Netherlands. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:1069–1076. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000224605.37317.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden M, Steinman L, Frederick J. Treating depression in older adults: challenges to implementing the recommendations of an expert panel. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):A26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein J, Pabst A, Weyerer S, et al. The assessment of met and unmet care needs in the oldest old with and without depression using the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): results of the AgeMooDe study. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson DG, Decker SL, Dwyer LL, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC, Metzger ED, Mitchell SL. Antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use among nursing home residents: findings from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. Am J Geriatr Psuchiatry. 2010;18:1078–1092. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6c0c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Téllez-Lapeira J, López-Torres Hidalgo J, García-Agua Soler N, Gálvez-Alcaraz L, Escobar-Rabadán F. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use and associated factors in the elderly. Eur J Psychiatry. 2016;30:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Unützer J, Patrick D, Diehr P, Simon G, Grembowski D, Katon W. Quality adjusted life years in older adults with depressive symptoms and chronic medical disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:15–33. doi: 10.1017/S1041610200006177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unützer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, Schoenbaum MC, Lin EHB, Della Penna RD, Powers D. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal X, Agustí A, Vallano A, et al. Elderly patients treated with psychotropic medicines admitted to hospital: associated characteristics and inappropriate use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72:755–764. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyer P, Martin LS. Improving geriatric mental health nursing care: making a case for going beyond psychotropic medications. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2003;12:11–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E, Davis C, Schaefer J, Von Korff M, Austin B. A survey of leading chronic disease management programs: are they consistent with the literature. J Nurs Care Qual. 2002;16:67–80. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nur. 2005;52:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Izmeth Z. Continuation and maintenance treatments for depression in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006727.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KC, Mottram PG, Vassilas CA. Psychotherapeutic treatments for older depressed people (Article No. CD004853) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004853.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Shier V, Saliba D. Transforming nursing home culture: evidence for practice and policy. Gerontologist. 2014;54:S1–S5. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Bowers BJ, Cohen LW, Grabowski DC, Horn SD, Kemper P, THRIVE Research Collaborative New evidence on the green house model of nursing home care: synthesis of findings and implications for policy, practice, and research. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(Suppl 1):475–496. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]