Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by social and interpersonal communication disabilities and repetitive motor activities. A deficit in social interaction may be due to motor and synchronization disabilities in individuals with ASD. These disabilities serve as a hindrance for the progression of day-to-day life. ASD individuals are known to have variations in the neural network contributing to changes in their oral-motor activity. As the brain has experience-dependent structural plasticity, these changes in the neural network can probably be reversed with appropriate treatment Music playing a universal role in human life has been studied for its therapeutic potential in rehabilitation of ASD individuals. Music and rhythm have shown a significant potential in improving the oral-motor activities of people affected by ASD. Music based interventions are being used for children diagnosed with ASDs to improve their social communication and motor skills. This article represents the possible role of rhythmic cueing for sensorimotor regulation in ASD individuals. This can serve as a base for further research for the impact of musical therapy on coordination and oral-motor synchronization of individuals diagnosed with ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Rhythm, Motor synchronization, Cortical plasticity, Cognitive function

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a multifaceted neurodevelopmental disorder that encompasses a group of behavioral conditions, frequently characterized by social and interpersonal communication disabilities, associated with repetitive motor activities. Although, Kanner (1943) described ASD for the first time in 1943 and Asperger reported about autistic psychopathy in 1944 (Fitzgerald, 2001), until 1980’s it was treated as a psychiatric disorder and children were misdiagnosed as being schizophrenic (Chisholm et al., 2015). Individuals with ASD may exhibit sensory dysfunction and problems in oral motor movements. Sensory dysfunction is prevalent in at least 70% of individuals with ASD (Tomchek and Dunn, 2007). The hearing and language disorders in children with autism are predominantly expressed as sensitive hearing which is exhibited by closing the ears, anger, crying, irritation and throwing objects while hearing certain noises. Sensory processing deficits typically manifest as hyper or hypo-reactivity to sensory input such as sensory-seeking or sensory-avoiding behaviors (Baranek et al., 2006; Baranek et al., 2007). Although ASD children with expressive language deficits are found to have motor and oral-motor impairments which are closely linked with speech production, fluency and clarity, language deficits are not described as a significant feature of ASD in DSM-V (Benítez-Burraco et al., 2016; Dalton, 2017).

Toddlers and young children with motor difficulties tend to remain nonverbal or exhibit problems with expressive speech and language, implying that speech discrepancies maybe secondary to oral-motor deficits. While ASD is considered as a developmental disorder, disruptions of social communication is rarely accepted as a result of challenges in speech and language. Further, research investigating the efficacy of alternative multisystem therapies for children with ASD is still growing, but interventions that specifically aim the oral-motor features in ASD are still scarce. These therapies may be necessary to effectively improve the social abilities of affected individuals. Current research suggests that, listening to music and rhythmic patterns improves attention in children with ASD, which may be a sign of improved sensory integration. Among the following four major music therapy (MT) interventions for ASD including auditory motor mapping training, melodic intonation therapy, improvisational music therapy and rhythm training, the potential of rhythm training to improve sensorimotor functioning in ASD is gaining momentum. In this review, we discuss about the prospective roles of music, rhythm, rhythmic entrainment, how rhythm enhances cortical plasticity and the effect of rhythm based music intervention as a rehabilitation method for ASD individuals.

MUSIC, BRAIN, AND CONNECTIVITY

Music is known to regulate arousal as well as attention in the brain and has the capacity to engage different areas in the brains of individuals with neurological conditions. Perception and production of auditory rhythms involves the subcortical and cortical brain networks consisting of the auditory cortex, basal ganglia, supplementary motor area (SMA), premotor cortices, and cerebellum (Koelsch, 2014). The architecture of the auditory system detect temporal patterns in auditory signals with great precision and speed (Shelton and Kumar, 2010). The whole brain responds to music and the pitch of the music is processed in the right temporal lobes which also governs speech, making it possible to use music to improve interpersonal communications. Moreover, the ASD brain is characterized as consisting of short range and long range communications. The short range consists of cortico-cortical connections and long range includes brain regions like the frontal, temporal, parietal, and subcortical areas (O’Reilly et al., 2017) Khan et al. (2013) have reported that both the short and long range connectivity are reduced among ASD and the disability of long-range networks are claimed to cause the social-emotional and communication deficiencies of autism. However, as the brain has experience-dependent structural plasticity, these changes in the neural network can probably be reversed with appropriate treatment.

Autistic individuals can possess “splinter skills” or “islets of ability” and approximately 10% of autistic entities have been reported to exhibit savant abilities in music, drawing, or calculation. The distinctive stimulus of music can offer ASD children the opportunity to interact socially and strive toward nonmusical social outcomes. Interestingly, studies had shown that autistic children were interested and perhaps more talented in music as compared to their unaffected counterparts, further exhibiting the possibility of developing MT (Applebaum et al., 1979; Molnar-Szakacs and Heaton, 2012). Traditional MT has been employed to cater to the social, communicative, and cognitive needs of ASD children (LaGasse, 2017). Cochrane meta-analysis suggested that music-based training significantly improves verbal and gestural communication abilities compared to placebo therapy in individuals with ASD (Gold et al., 2006). In many countries, MT has been practiced as a useful intervention to improve social interaction, verbal communication and socio emotional reciprocity (Geretsegger et al., 2014). Quintin et al. (2011) have further claimed that the ability of ASD individuals to recognize the emotions behind music were similar to that of other individuals, making music a potential therapeutic strategy.

RHYTHM IN MUSIC

Rhythm, the primary structural feature of music denotes the division of time through distinct order. Similarly, in our human life, the natural and extemporaneous body movements are a demonstration of inner timing. The developmental defects in the brainstem and cerebellum inutero can lead to deficits in sensory perception in ASD (Trevarthen and Delafield-Butt, 2013). Trevarthen and Daniel (2005) suggested that, disorganized rhythm and synchrony in infants can be the early signs of ASD and Rett’s syndrome. Chen et al. (2008) used a pulse-tapping method and have reported that, listening to music recruits motor associated regions of the brain further connecting it to movement and development. Rhythmicity plays a vital role in development and timing is critical in motor control and cognitive functions (Murphy, 2015a; Smith et al., 2014). Inutero, a fetus’s neural circuits and auditory memory are forming and at five months, it can feel the rhythm of the mother’s heartbeat and respiration. After birth, during development, each child finds a particular motor rhythm which will endure consistently throughout life. Rhythm also incorporates sensory perception and motor entrainment, which results into complex cognitive functions and motor adaptations. Remarkably, brain rhythms are heritable components of brain function and have been connected to computational primitives of language (Benítez-Burraco and Murphy, 2016; Knyazev, 2007; Murphy, 2015b) at the brain level. Further, rhythm has also been associated with language shortfalls, neural malfunction and autism (Overy and Turner, 2009). Social interactions that include eye contact, turn taking. Synchrony and imitation can be introduced to induce and enhance social and behavioral skills in children with ASD. Furthermore, it has been reported by studies that the interaction between the auditory and motor system can be utilized in rehabilitation therapies for individuals with motor condition. Neuroscience information regarding alpha, delta and gamma rhythmic oscillations in the brain continue increasing, these oscillation being a key to arousal, anxiety and relaxation responses, must be further researched in individuals with ASD for therapeutic advancement (Thaut et al., 1991; Thaut et al., 1997).

RHYTHM AND RHYTHMIC ENTRAINMENT

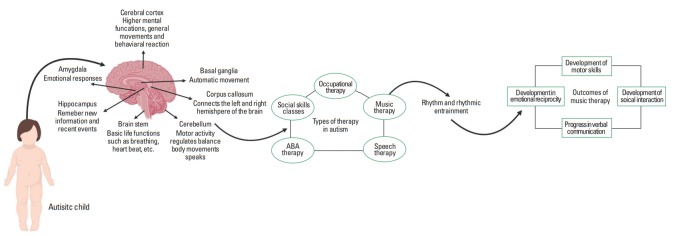

Rhythmic entrainment introduced the first motor theory for the function of auditory rhythm and music in therapy. Rhythmic entrainment is known to play a role in affecting heartbeat, pain reduction and muscle relaxation, and music-mediated imagery among in MT (Bengtsson et al., 2009). Entrainment to music involves a large network of brain structures (Grahn, 2012; Phillips-Silver et al., 2010; Sihvonen et al., 2017) which involves auditory, visual, proprioceptive and vestibular perception. The complex process requires motor synchronization, attention, performance and coordination within and across individuals (Sihvonen et al., 2017). Rhythmic entrainment methods connect an individual with their own body rhythm and also connect them nonverbally with other individuals. Subsequent studies on music entrainment contributed to the necessity to codify and standardize rhythmic-musical application for motor rehabilitation in affected individuals (Galińska, 2015; Thaut et al., 2015) (Fig. 1). It has also been reported that, synchronization, entrainment of rhythmic vocalizations and bimanual motor actions can effectively stimulate the speech, motor and language networks in ASD. These findings laid the foundation for neurologic MT (NMT). NMT will use rhythm as template to accomplish complex motor tasks by activating compensatory neural networks. Music can contribute to neurological rehabilitation in various ways that include, rhythmic stimulation and entrainment, patterned information processing, and differential neurological processing of musical components by means of different brain structures, and the affective-aesthetic response include arousal, motivation and production of emotions (Thaut et al., 2009). In NMT, rhythm has stimulating, cueing and coordinative function, through cortical plasticity (Boso et al., 2007). NMT is available as a standard treatment that has been accepted as therapy over the past decade. Since the central rhythm is disrupted in autistic individuals similar to that of patients with a damaged cerebellum, music can be used to synchronize movements and evoke emotions in affected individuals. NMT can serve as a therapeutic tool to bring natural rhythmicity to affected individuals promoting the reorganization of abnormal circuits (Chen et al., 2008; Kornysheva et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

Graphical abstract of the present study. ABA, applied behavior analysis.

RHYTHM, CORTICAL PLASTICITY, AND AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER

Musical training involves the cortical areas of movement such as, the precentral gyrus, SMA (Whitall et al., 2011), the cerebellum (Luft et al., 2004) auditory, occipital, sensory, frontal brain areas and the anterior corpus callosum and improves cortical plasticity and promotes structural and functional connectivity in the brain (Hardy and LaGasse, 2013). Further, Chen et al. (2008) have suggested an integral association between auditory and motor systems in the milieu of rhythm. Interestingly, Kornysheva et al. (2010) have compared the effect of desired to not desired musical rhythms on the premotor and cerebellar areas using functional magnetic resonance imaging and indicated that the desired tempo improved the activity in the ventral premotor cortex. It has also been found that structural and functional variances in the sensorimotor regions of the cerebellum and sensorimotor cerebro-cerebellar circuits can cause motor control disability and repetitive and stereotyped behaviors in ASD (D’Mello and Stoodley, 2015). Hence, music can be used as a tool to improve cortical plasticity in individuals with the disorder. It can be used to rewire sensorimotor cerebro-cerebellar circuits to improve motor control and repetitive behaviors. Rhythm can be used to couple auditory motor functioning and increase the motor function of ASD individuals.

REHABILITATION THROUGH RHYTHMIC STIMULI IN AUTISM

If rhythmic stimulus is applied systematically, it has the potential to enhance the timings of neural networks in addition to the ones associated with movement, and the interventions may have a greater impact on the patients. This may be one reason that studies on MT and ASD have demonstrated improved social (Brownell, 2002; Finnigan and Starr, 2010; Kern and Aldridge, 2006; Kim et al., 2008)) and communication skills (Lim, 2010; Wan et al., 2011). Berger’s study based on the hypothesis that patterned, tempo-based, rhythm interventions, brought systemic pacing under control, eased repetitive behaviors and also reduced anxiety in ASD individuals (Berger, 2012). Corriveau and Goswami (2009) discovered the relationship between rhythmic motor entrainment in children with speech and language impairments, and also its possible implication in dyslexia. An exploratory study by Sharda et al. (2018) observed that music improves social communication and auditory motor association in individuals with ASD. Report of the study showed that, children with proprioceptive deficits in ASD performed superior in auditory and visual attention responsibilities after receiving rhythmic proprioceptive input than children who received only the proprioceptive input. Suggesting a significant role of rhythmic input in these individuals. Kalas (2012) in his report has suggested that, simple rhythm facilitates attention in all functioning levels of ASD. Additionally it has been found that predictable rhythmic structure are important for movement, and that unconscious motor response to rhythm can regulate motor activity, further reinforcing the effect of predictable rhythm in movement (Molinari et al., 2007). Moreover, Stevens and Byron (2009) have reported that Predictable rhythmic structure creates a sense of expectation, focusing on the emotional benefits of MT. As rhythm assists in facilitating motor stability, Hardy and LaGasse (2013) have found that rhythmic synchronization and systematic rhythmic cueing can increase cortical plasticity. Further, ASD individuals had also shown an increase in motor skills after receiving a biweekly rhythmic program (Srinivasan et al., 2015) accentuating the importance of MT in ASD. Interestingly, it has also been established that individuals with ASD were able to synchronize rhythm just as well as their typically developed counterparts (Tryfon et al., 2017). Thus the unique correlation (Thaut et al., 2005). Improvement in motor skills can encourage ASD individuals to demonstrate their full cognitive, social, and communicative potential to respond socially and individually.

CONCLUSIONS

Apart from social and communication deficits, movement and language differences in ASD also play a vital part in development, and hence merits further investigation. The individuals affected with ASD often lack social, interpersonal and motor skills, providing a hindrance to their everyday life. Hence, clinical treatment of ASD must focus on motor coordination and the improvement of functional motor skills along with other aspects of ASD. Auditory cues are progressively used in movement rehabilitation, but controlled clinical trials are very rare and may not yield positive results each time. Rhythmic auditory cueing can be used as an appropriate technique to stabilize the movement patterns and simplify a motor plan. Rhythmic intervention may serve as a therapeutic tool to increase the motor, language and personal skills of ASD individuals leading to a better quality of life. Hence, further research is essential to establish the association between rhythm and movement in ASD individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Science and Engineering research board (SERB) (ECR/2016/001688), Government of India, New Delhi for funding this review. Biorender online software is used to create the graphical abstract of the study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- Applebaum E, Egel AL, Koegel RL, Imhoff B. Measuring musical abilities of autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord. 1979;9:279–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01531742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, Boyd BA, Poe MD, David FJ, Watson LR. Hyperresponsive sensory patterns in young children with autism, developmental delay, and typical development. Am J Ment Retard. 2007;112:233–245. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[233:HSPIYC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, David FJ, Poe MD, Stone WL, Watson LR. Sensory experiences questionnaire: discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson SL, Ullén F, Ehrsson HH, Hashimoto T, Kito T, Naito E, Forssberg H, Sadato N. Listening to rhythms activates motor and premotor cortices. Cortex. 2009;45:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Burraco A, Lattanzi W, Murphy E. Language impairments in ASD resulting from a failed domestication of the human brain. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:373. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Burraco A, Murphy E. The oscillopathic nature of language deficits in autism: from genes to language evolution. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:120. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger DS. Pilot study investigating the efficacy of tempo-specific rhythm interventions in music-based treatment addressing hyper-arousal, anxiety, system pacing, and redirection of fight-or-flight fear behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) J Biomusic Eng. 2012;2:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Boso M, Emanuele E, Minazzi V, Abbamonte M, Politi P. Effect of long-term interactive music therapy on behavior profile and musical skills in young adults with severe autism. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:709–712. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell MD. Musically adapted social stories to modify behaviors in students with autism: four case studies. J Music Ther. 2002;39:117–144. doi: 10.1093/jmt/39.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Penhune VB, Zatorre RJ. Listening to musical rhythms recruits motor regions of the brain. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2844–2854. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm K, Lin A, Abu-Akel A, Wood SJ. The association between autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a review of eight alternate models of co-occurrence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corriveau KH, Goswami U. Rhythmic motor entrainment in children with speech and language impairments: tapping to the beat. Cortex. 2009;45:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton JC, Crais ER, Velleman SL. Joint attention and oromotor abilities in young children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J Commun Disord. 2017;69:27–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Mello AM, Stoodley CJ. Cerebro-cerebellar circuits in autism spectrum disorder. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:408. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnigan E, Starr E. Increasing social responsiveness in a child with autism. A comparison of music and non-music interventions. Autism. 2010;14:321–348. doi: 10.1177/1362361309357747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M. Autistic psychopathy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:870. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galińska E. Music therapy in neurological rehabilitation settings. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49:835–846. doi: 10.12740/PP/25557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geretsegger M, Elefant C, Mössler KA, Gold C. Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD004381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold C, Wigram T, Elefant C. Music therapy for autistic spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn JA. Neural mechanisms of rhythm perception: current findings and future perspectives. Top Cogn Sci. 2012;4:585–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy MW, LaGasse AB. Rhythm, movement, and autism: using rhythmic rehabilitation research as a model for autism. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:19. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalas A. Joint attention responses of children with autism spectrum disorder to simple versus complex music. J Music Ther. 2012;49:430–452. doi: 10.1093/jmt/49.4.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern P, Aldridge D. Using embedded music therapy interventions to support outdoor play of young children with autism in an inclusive community-based child care program. J Music Ther. 2006;43:270–294. doi: 10.1093/jmt/43.4.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Gramfort A, Shetty NR, Kitzbichler MG, Ganesan S, Moran JM, Lee SM, Gabrieli JD, Tager-Flusberg HB, Joseph RM, Herbert MR, Hämäläinen MS, Kenet T. Local and long-range functional connectivity is reduced in concert in autism spectrum disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3107–3112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214533110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Wigram T, Gold C. The effects of improvisational music therapy on joint attention behaviors in autistic children: a randomized controlled study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1758–1766. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev GG. Motivation, emotion, and their inhibitory control mirrored in brain oscillations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:377–395. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:170–180. doi: 10.1038/nrn3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornysheva K, von Cramon DY, Jacobsen T, Schubotz RI. Tuning-in to the beat: aesthetic appreciation of musical rhythms correlates with a premotor activity boost. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:48–64. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGasse AB. Social outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder: a review of music therapy outcomes. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2017;8:23–32. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S106267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HA. Effect of “developmental speech and language training through music” on speech production in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Music Ther. 2010;47:2–26. doi: 10.1093/jmt/47.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft AR, McCombe-Waller S, Whitall J, Forrester LW, Macko R, Sorkin JD, Schulz JB, Goldberg AP, Hanley DF. Repetitive bilateral arm training and motor cortex activation in chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1853–1861. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari M, Leggio MG, Thaut MH. The cerebellum and neural networks for rhythmic sensorimotor synchronization in the human brain. Cerebellum. 2007;6:18–23. doi: 10.1080/14734220601142886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar-Szakacs I, Heaton P. Music: a unique window into the world of autism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1252:318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. Labels, cognomes, and cyclic computation: an ethological perspective. Front Psychol. 2015a;6:715. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. The brain dynamics of linguistic computation. Front Psychol. 2015b;6:1515. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly C, Lewis JD, Elsabbagh M. Is functional brain connectivity atypical in autism? A systematic review of EEG and MEG studies. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overy K, Turner R. The rhythmic brain. Cortex. 2009;45:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Silver J, Aktipis CA, Bryant GA. The ecology of entrainment: foundations of coordinated rhythmic movement. Music Percept. 2010;28:3–14. doi: 10.1525/mp.2010.28.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintin EM, Bhatara A, Poissant H, Fombonne E, Levitin DJ. Emotion perception in music in high-functioning adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:1240–1255. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharda M, Tuerk C, Chowdhury R, Jamey K, Foster N, Custo-Blanch M, Tan M, Nadig A, Hyde K. Music improves social communication and auditory-motor connectivity in children with autism. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:231. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0287-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton J, Kumar GP. Comparison between auditory and visual simple reaction times. Neurosci Med. 2010;1:30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sihvonen AJ, Särkämö T, Leo V, Tervaniemi M, Altenmüller E, Soinila S. Music-based interventions in neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:648–660. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Rathcke T, Cummins F, Overy K, Scott S. Communicative rhythms in brain and behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0389. 20130389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan SM, Park IK, Neelly LB, Bhat AN. A comparison of the effects of rhythm and robotic interventions on repetitive behaviors and affective states of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2015;18:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C, Byron T. Universals in music processing: entrainment, acquiring expectations, and learning. In: Hallam S, Cross I, Thaut M, editors. Oxford handbook of music psychology. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Thaut M, Schleiffers S, Davis W. Analysis of EMG activity in biceps and triceps muscle in an upper extremity gross motor task under the influence of auditory rhythm. J Music Ther. 1991;28:64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Thaut MH, McIntosh GC, Hoemberg V. Neurobiological foundations of neurologic music therapy: rhythmic entrainment and the motor system. Front Psychol. 2015;5:1185. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaut MH, McIntosh GC, Rice RR. Rhythmic facilitation of gait training in hemiparetic stroke rehabilitation. J Neurol Sci. 1997;151:207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaut MH, Peterson DA, McIntosh GC. Temporal entrainment of cognitive functions: musical mnemonics induce brain plasticity and oscillatory synchrony in neural networks underlying memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1060:243–254. doi: 10.1196/annals.1360.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaut MH, Stephan KM, Wunderlich G, Schicks W, Tellmann L, Herzog H, McIntosh GC, Seitz RJ, Hömberg V. Distinct cortico-cerebellar activations in rhythmic auditory motor synchronization. Cortex. 2009;45:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchek SD, Dunn W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:190–200. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen C, Daniel S. Disorganized rhythm and synchrony: early signs of autism and Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 2005;27(Suppl 1):S25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen C, Delafield-Butt JT. Autism as a developmental disorder in intentional movement and affective engagement. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:49. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryfon A, Foster NE, Ouimet T, Doyle-Thomas K, Anagnostou E, Sharda M, Hyde KL. Auditory-motor rhythm synchronization in children with autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2017;35:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wan CY, Bazen L, Baars R, Libenson A, Zipse L, Zuk J, Norton A, Schlaug G. Auditory-motor mapping training as an intervention to facilitate speech output in non-verbal children with autism: a proof of concept study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitall J, Waller SM, Sorkin JD, Forrester LW, Macko RF, Hanley DF, Goldberg AP, Luft A. Bilateral and unilateral arm training improve motor function through differing neuroplastic mechanisms: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:118–129. doi: 10.1177/1545968310380685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]