Abstract

Background

Inability to tolerate statins because of muscle symptoms contributes to uncontrolled cholesterol levels and insufficient cardiovascular risk reduction. Bempedoic acid, a prodrug that is activated by a hepatic enzyme not present in skeletal muscle, inhibits ATP‐citrate lyase, an enzyme upstream of β‐hydroxy β‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A reductase in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway.

Methods and Results

The phase 3, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled CLEAR (Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic acid, an ACL‐Inhibiting Regimen) Serenity study randomized 345 patients with hypercholesterolemia and a history of intolerance to at least 2 statins (1 at the lowest available dose) 2:1 to bempedoic acid 180 mg or placebo once daily for 24 weeks. The primary end point was mean percent change from baseline to week 12 in low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol. The mean age was 65.2 years, mean baseline low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol was 157.6 mg/dL, and 93% of patients reported a history of statin‐associated muscle symptoms. Bempedoic acid treatment significantly reduced low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol from baseline to week 12 (placebo‐corrected difference, −21.4% [95% CI, −25.1% to −17.7%]; P<0.001). Significant reductions with bempedoic acid versus placebo were also observed in non–high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (−17.9%), total cholesterol (−14.8%), apolipoprotein B (−15.0%), and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (−24.3%; P<0.001 for all comparisons). Bempedoic acid was safe and well tolerated. The most common muscle‐related adverse event, myalgia, occurred in 4.7% and 7.2% of patients who received bempedoic acid or placebo, respectively.

Conclusions

Bempedoic acid offers a safe and effective oral therapeutic option for lipid lowering in patients who cannot tolerate statins.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT02988115.

Keywords: hypercholesterolemia, lipids, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, muscle, statin

Subject Categories: Clinical Studies, Lipids and Cholesterol, Primary Prevention, Secondary Prevention, Cardiovascular Disease

Short abstract

See Editorial by Jia and Virani

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The phase 3 CLEAR (Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic acid, an ACL‐Inhibiting Regimen) Serenity clinical trial demonstrates the lipid‐lowering efficacy of bempedoic acid, a first‐in‐class, prodrug, small‐molecule inhibitor of ATP‐citrate lyase, among patients with established statin intolerance and elevated low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol who were receiving stable background therapy.

Muscle‐related symptoms contributed to the history of statin intolerance for almost all patients.

Although bempedoic acid acts on the same cholesterol biosynthesis pathway as statins, the muscle‐related adverse event rate in CLEAR Serenity with bempedoic acid, which is not activated in skeletal muscle, did not differ from placebo, even among patients who had experienced muscle‐related symptoms while on statin therapy.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Bempedoic acid may offer a novel treatment option to reach low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol goals for the large number of patients who have difficulty tolerating statin treatment due to muscle‐related side effects.

Consistent lipid lowering across patient subgroups and when administered as monotherapy or when added to stable background lipid‐lowering therapy indicate the potential for bempedoic acid to provide an effective, oral therapeutic alternative that is complementary to statins and other nonstatin therapies.

Introduction

Patients who cannot tolerate a statin‐based treatment regimen present a particular challenge for lipid management and cardiovascular event risk reduction.1, 2 Registries and observational studies have reported statin intolerance prevalence rates of 7% to 29%, with the predominant symptoms being muscle‐related side effects.3 Statin‐associated muscle symptoms account for >90% of side effects attributed to statins4 and contribute to the high rate of nonadherence and discontinuation frequently observed with statin therapy.3, 5, 6, 7 As treatment with a statin, the cornerstone of lipid‐lowering therapy, is not suitable at standard doses for individuals with intolerance, these patients are less likely to achieve adequate antiatherogenic lipid reduction and are, thus, at increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with statin‐treated patients.8, 9, 10 To reduce cardiovascular risk in these patients, additional pharmacologic lipid‐lowering options are needed.11, 12

Bempedoic acid (Esperion Therapeutics Inc, Ann Arbor, MI) is a first‐in‐class, small‐molecule inhibitor of ATP‐citrate lyase, a component of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway that works upstream of β‐hydroxy β‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A. Bempedoic acid is a prodrug that is activated by very‐long‐chain acyl‐CoA synthetase‐1, an enzyme that is not present in skeletal muscle.13 Therefore, although bempedoic acid acts on the same pathway as statins, lack of the activating enzyme in skeletal muscle may prevent the muscular adverse effects associated with statins.13 In phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials, bempedoic acid significantly reduced atherogenic lipoproteins and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP) levels, and was associated with a low risk for adverse events typically associated with statins such as muscle‐related symptoms and new‐onset diabetes mellitus.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Here, we report the results of CLEAR (Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic acid, an ACL‐Inhibiting Regimen) Serenity, a phase 3 clinical trial designed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of bempedoic acid 180 mg daily versus placebo in statin‐intolerant patients requiring lipid‐lowering therapy for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.

Methods

Patients

The CLEAR Serenity trial (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov unique identifier: NCT02988115) enrolled adult men and women receiving stable background lipid‐modifying therapy who required additional lipid‐lowering for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular events. At the initial screening visit, fasting calculated low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) was required to be ≥130 mg/dL for primary prevention patients (ie, those requiring lipid‐lowering therapy based on national guidelines) and ≥100 mg/dL for patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (diagnosed via genotyping, World Health Organization/Dutch Lipid Clinical Network Criteria with a score >8 points, or Simon Broome Register Diagnostic Criteria with an assessment of “definite heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia”) and/or who had a secondary prevention indication (coronary artery disease, symptomatic peripheral arterial disease, and/or cerebrovascular atherosclerotic disease). All patients had a history of statin intolerance, defined as the inability to tolerate at least 2 statins, 1 at a low dose, due to a prior adverse event that started or increased during statin therapy and resolved or improved when statin therapy was discontinued. Low‐dose statin therapy was defined as an average daily dose of rosuvastatin 5 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, simvastatin 10 mg, lovastatin 20 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, fluvastatin 40 mg, or pitavastatin 2 mg.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had experienced a cardiovascular or cerebrovascular event or procedure, or had undergone an endovascular or surgical intervention for peripheral vascular disease within 3 months before screening, or if they planned to undergo a major surgical or interventional procedure. Patients were also excluded if they had total fasting triglycerides ≥500 mg/dL, renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or glomerular nephropathy, body mass index ≥50 kg/m2, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled hypothyroidism, liver disease or dysfunction, gastrointestinal conditions or procedures that could affect drug absorption, hematologic or coagulation disorders, active malignancy, or unexplained creatine kinase elevations >3 times the upper limit of normal. Certain lipid‐modifying therapies were also prohibited, including mipomersen within 6 months of screening, lomitapide, or apheresis within 3 months of screening; investigational cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibitors within 2 years of screening (with the exception of evacetrapib, which must have been discontinued ≥3 months prior to screening); and red yeast rice extract and berberine‐containing products within 2 weeks of screening. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Data S1.

Study Design

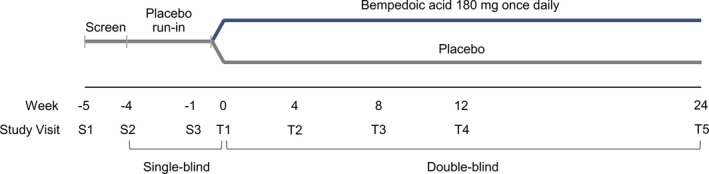

This phase 3, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study was conducted at 67 sites in the United States and Canada from November 16, 2016, to March 16, 2018. After a 5‐week screening phase, which included a 4‐week, single‐blind, placebo run‐in period, patients who satisfied eligibility criteria were stratified by treatment indication (primary prevention versus secondary prevention and/or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia), then randomized 2:1 to treatment with oral bempedoic acid 180 mg or placebo once daily for 24 weeks in a double‐blind treatment phase (Figure 1). Patients and study personnel were blinded to randomized study treatment assignments and to postrandomization values for lipid and biomarker measures that may have inadvertently suggested treatment assignment.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Patients were allowed to continue stable (ie, used for ≥4 weeks prior to screening) background lipid‐modifying therapy with selective cholesterol absorption inhibitors, bile acid sequestrants, fibrates (except gemfibrozil in patients receiving a very‐low‐dose statin), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors (if ≥3 doses were received prior to screening), or niacin, either alone or in combination. Patients tolerating very‐low‐dose statin therapy were permitted to continue statin therapy throughout the study, provided that the drug and dose were stable and well tolerated. Very‐low‐dose statin therapy was defined as an average daily dose of rosuvastatin <5 mg, atorvastatin <10 mg, simvastatin <10 mg, lovastatin <20 mg, pravastatin <40 mg, fluvastatin <40 mg, or pitavastatin <2 mg.

The study protocol and informed consent documents were approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site, and the study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles established by the International Conference on Harmonisation and Good Clinical Practice guidelines in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki. All study participants provided written informed consent. Data collection was performed by the investigators with assistance from the clinical research organization IQVIA (Durham, NC), and data analysis was conducted by IQVIA. All authors had access to the study data and take responsibility for the integrity, analysis, and representation of the data herein. At this time, the data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures.

Assessments and End Points

Clinical laboratory samples were collected and analyzed for basic fasting lipids (LDL‐C, non–high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol [non–HDL‐C], total cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL‐C], and triglycerides) at the initial and final screening visits (weeks −5 and −1), at baseline, and at weeks 4, 12, and 24. LDL‐C concentration was derived from total cholesterol, HDL‐C, and triglyceride values using the Friedewald formula; however, direct measurement of LDL‐C was performed if triglycerides were >400 mg/dL or LDL‐C was ≤50 mg/dL. Apolipoprotein B (apoB) and hsCRP levels were measured at baseline and at weeks 12 and 24. All lipid and biomarker analyses were performed at a central laboratory (Q2 Solutions, Marietta, GA). Postrandomization efficacy end point values were not made available to patients or study personnel.

The primary end point was the percent change from baseline to week 12 in LDL‐C. Secondary end points included percent change from baseline to week 24 in LDL‐C; percent change from baseline to week 12 in non–HDL‐C, total cholesterol, apoB, and hsCRP; and absolute change from baseline to weeks 12 and 24 in LDL‐C. Percent change from baseline to week 24 in non–HDL‐C, total cholesterol, apoB, and hsCRP, as well as percent change from baseline to weeks 12 and 24 in triglycerides and HDL‐C were also assessed.

Safety and tolerability were evaluated through continuous monitoring of treatment‐emergent adverse events, clinical safety laboratory findings, vital sign measurements, physical examinations, electrocardiograph readings, and cardiovascular event rates. Cardiovascular events, including major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, coronary revascularization) and non‐MACE events (noncardiovascular death, noncoronary arterial revascularization, hospitalization for heart failure), were adjudicated by a blinded, independent expert clinical event committee (C5 Research, Cleveland, OH). Adverse events potentially related to muscular safety were recorded on a muscle‐specific electronic case report form, and analysis of muscle‐related adverse events included the following Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms: muscular weakness, muscle necrosis, muscle spasms, myalgia, myoglobin blood increased, myoglobin blood present, myoglobin urine present, myoglobinemia, myoglobinuria, myopathy, myopathy toxic, necrotizing myositis, pain in extremity, and rhabdomyolysis.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 300 randomized patients (200 assigned to bempedoic acid and 100 assigned to placebo) was chosen to provide >95% power to detect a 15% difference between the bempedoic acid and placebo treatment groups in LDL‐C percent change from baseline to week 12. This calculation was based on a 2‐sided t test at the 5% level of significance and a common standard deviation of 15%.

Primary efficacy analyses were performed using the intention‐to‐treat population, which included all randomized patients. The primary and key secondary efficacy end points were analyzed using an analysis of covariance model, with treatment group as the main effect adjusting for patient type (primary versus secondary prevention/heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia) and baseline values. Baseline for LDL‐C, non–HDL‐C, and total cholesterol was defined as the mean of the last 2 nonmissing values on or before study day 1. Baseline for apoB and hsCRP was defined as the predose value on day 1. Missing data were imputed using a pattern mixture model. For patients with missing data who had already discontinued the study drug (bempedoic acid or placebo), the missing values were imputed using data from placebo group patients only (ie, their responses were assumed to be similar to patients in the placebo group once they were off treatment). For patients who had missing data and were adherent to study treatment, their missing data were imputed using patient data from their respective treatment group. Means, least‐squares means, and standard errors were calculated for individual treatment groups, and 95% CIs and P values were determined for the placebo‐corrected change from baseline. Data are presented as placebo‐corrected least‐squares mean changes, unless otherwise indicated. For hsCRP, nonparametric analyses (Wilcoxon rank‐sum test) with Hodges‐Lehmann estimates and CIs were performed. A stepdown approach was used to test the primary efficacy end point followed by specific secondary efficacy end points sequentially in the following order: LDL‐C (week 12), LDL‐C (week 24), non–HDL‐C (week 12), total cholesterol (week 12), apoB (week 12), and hsCRP (week 12). In this hierarchical testing structure, each hypothesis was tested at a significance level of 0.05, 2‐sided. Statistical significance at each step was required to test the next hypothesis. In this study, all end points included in the step‐down procedure achieved the prespecified significance level; thus, the overall type I error was preserved. Had statistical significance not been achieved at any step, any subsequent end points would be considered as descriptive only. Additional time points and lipid measures that were not part of the hierarchical testing structure, including changes in triglycerides and HDL‐C, were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Predefined sensitivity analyses for all primary and secondary efficacy end points were performed without imputation for missing data, and included data prior to any postbaseline change in concomitant lipid‐modifying therapy (adjunctive lipid‐modifying therapy analysis) and data from the on‐treatment period (on‐treatment analysis). Subgroup analyses were performed for the primary end point using analysis of covariance without imputation for missing data on the following groups: cardiovascular disease risk category (primary versus secondary prevention), baseline LDL‐C category (<130 mg/dL, ≥130 and <160 mg/dL, ≥160 mg/dL), history of diabetes mellitus, age (<65, ≥65 to <75, ≥75 years), race, sex, body mass index category (<25 kg/m2, ≥25 and <30 kg/m2, ≥30 kg/m2), and background lipid‐modifying therapy (statin, nonstatin, none). Safety analyses included all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug. No statistical comparisons were made between treatment groups for safety data. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Disposition

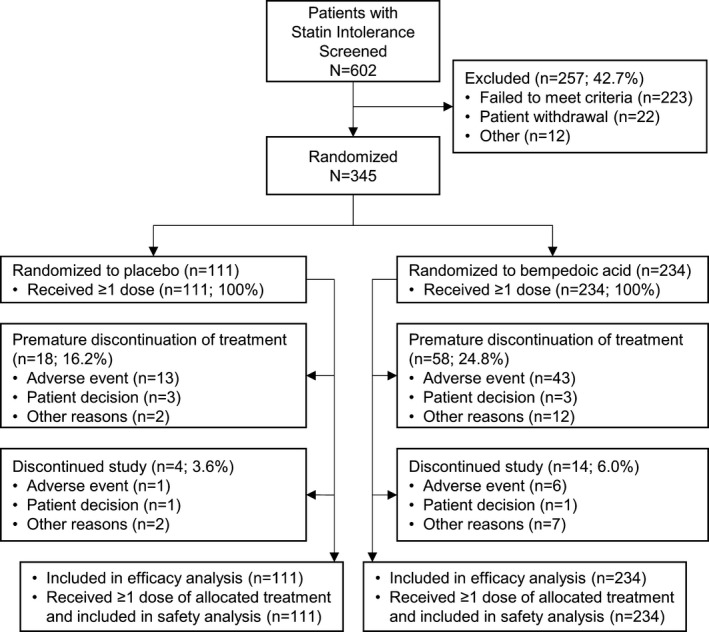

Six hundred two patients with hypercholesterolemia and statin intolerance were screened, and 345 patients were randomized to treatment with bempedoic acid (n=234) or placebo (n=111; Figure 2). A total of 327 patients (94.8%) completed the study, with 78.0% (n=269) receiving the study drug throughout. Fifty‐eight (24.8%) patients in the bempedoic acid treatment group and 18 (16.2%) patients in the placebo treatment group discontinued study treatment (Figure 2). Mean study‐drug exposure was similar in the bempedoic acid and placebo groups (147.4 and 154.1 days, respectively). All randomized patients were included in the intention‐to‐treat and safety populations.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition.

Baseline Characteristics

The study population was 56.2% female, 89.0% white, and had a mean age of 65.2±9.5 years (Table 1). A greater proportion of patients were enrolled for primary versus secondary prevention (61.2% and 38.8%, respectively). Two percent of patients had heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. A history of diabetes mellitus and/or hypertension was common in both treatment arms. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were generally balanced between treatment groups.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristicsa

| Parameter | Placebo (n=111) | Bempedoic Acid (n=234) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yb | 65.1±9.2 | 65.2±9.7 |

| Women, % (n) | 55.0 (61) | 56.8 (133) |

| Race, % (n) | ||

| White | 86.5 (96) | 90.2 (211) |

| Black or African American | 9.0 (10) | 6.8 (16) |

| Other | 4.5 (5) | 3.0 (7) |

| CVD risk category, % (n) | ||

| Primary prevention | 60.4 (67) | 61.5 (144) |

| Secondary prevention | 39.6 (44) | 38.5 (90) |

| Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, % (n) | 2.7 (3) | 1.7 (4) |

| History of diabetes mellitus, % (n) | 23.4 (26) | 26.9 (63) |

| History of hypertension, % (n) | 67.6 (75) | 67.5 (158) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 b | 30.6±5.2 | 30.1±5.8 |

| eGFR category, % (n) | ||

| ≥90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 14.4 (16) | 24.8 (58) |

| 60 to <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 62.2 (69) | 59.4 (139) |

| <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 23.4 (26) | 15.8 (37) |

| Background lipid‐modifying therapy, % (n) | ||

| Very‐low‐dose statin | 9.9 (11) | 7.7 (18) |

| Nonstatin | 29.7 (33) | 35.5 (83) |

| None | 60.4 (67) | 56.8 (133) |

| Reasons for statin intolerance, % (n) | ||

| Muscle symptoms | 94.6 (105) | 92.7 (217) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 8.1 (9) | 11.1 (26) |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 6.3 (7) | 6.4 (15) |

| Generalized fatigue | 2.7 (3) | 5.1 (12) |

| Cognitive decline | 2.7 (3) | 3.0 (7) |

| Elevated creatine kinase | 0.9 (1) | 0.9 (2) |

| Depression | 0 | 0.4 (1) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dLb | 241.1±44.3 | 245.7±47.3 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dLb | 155.6±38.8 | 158.5±40.4 |

| LDL‐C category, % (n) | ||

| <130 mg/dL | 25.2 (28) | 24.4 (57) |

| ≥130 and <160 mg/dL | 30.6 (34) | 32.9 (77) |

| ≥160 mg/dL | 44.1 (49) | 42.7 (100) |

| HDL‐C, mg/dLb | 50.4±14.4 | 52.2±14.5 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dLc | 164.0 (120.0, 225.5) | 156.5 (114.5, 219.0) |

| Non–HDL‐C, mg/dLb | 190.7±43.8 | 193.5±45.1 |

| apoB, mg/dLb | 141.9±30.4 | 141.0±31.6 |

| hsCRP, mg/Lc | 2.78 (1.21, 5.15) | 2.92 (1.34, 5.29) |

Baseline for LDL‐C, HDL‐C, non–HDL‐C, triglycerides, and total cholesterol was defined as the mean of the last 2 nonmissing values on or prior to day 1. Baseline for apoB and hsCRP was defined as the last nonmissing value on or prior to day 1. Baseline for all other parameters was defined as last measurement before the first dose of study drug. apoB indicates apolipoprotein B; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol.

The only statistically significant difference between treatment groups was eGFR category (P=0.044), with a greater proportion of patients with normal renal function in the bempedoic acid group and a greater proportion of patients with mild or moderate renal impairment in the placebo group.

Data are means±SDs.

Data are medians (Q1, Q3).

At baseline, mean LDL‐C was 157.6±39.9 mg/dL, non–HDL‐C was 192.6±44.6 mg/dL, mean total cholesterol was 244.2±46.3 mg/dL, apoB was 141.3±31.2 mg/dL, and median hsCRP was 2.90 (Q1, Q3: 1.29, 5.15) mg/L. The majority of patients (58.0%) were not receiving any concomitant lipid‐modifying therapy. One third of patients were on background nonstatin therapy (the most common agents were ezetimibe and fish oil), and very‐low‐dose statin therapy was used by 8.4% of patients. All patients had a history of prior statin use; the most frequently reported were atorvastatin and rosuvastatin. Documented statin intolerance attributable to muscle complaints (with or without other symptoms) was reported by 93.3% of patients. Approximately one third of patients who had experienced statin intolerance attributable to muscle symptoms had tried 3 or more statin medications.

Change From Baseline in Lipids and Biomarkers

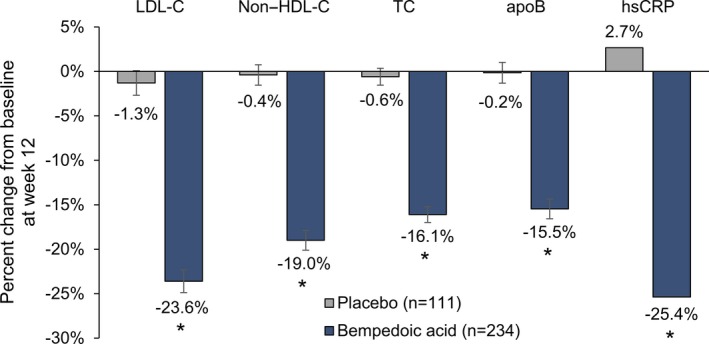

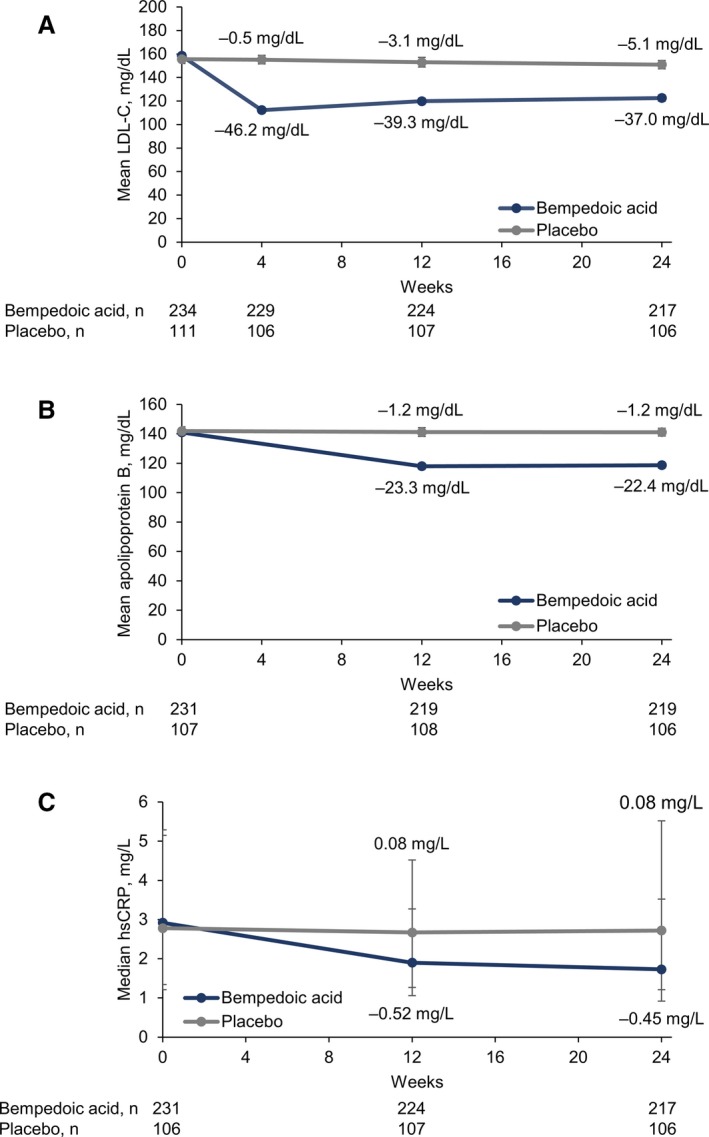

Treatment with bempedoic acid reduced LDL‐C significantly more than placebo at week 12 (placebo‐corrected change from baseline, −21.4% [95% CI −25.1% to −17.7%]; P<0.001, Figure 3). Reductions in LDL‐C were evident at the first postbaseline study visit (week 4) and were maintained throughout the study (Figure 4A). Significant reductions with bempedoic acid versus placebo were also observed for all secondary lipid and biomarker end points at week 12 (P<0.001; Figure 3). Changes from baseline were −17.9% (95% CI −21.1% to −14.8%) for non–HDL‐C, −14.8% (95% CI, −17.3% to −12.2%) for total cholesterol, and −15.0% (95% CI, −18.1% to −11.9%) for apoB, respectively. The location shift from baseline to week 12 for hsCRP was −24.3% (asymptotic confidence limits, −35.9% to −12.7%). Improvements in these parameters were maintained at week 24 (Figure 4 and Table 2). Changes in triglycerides were minimal and similar with bempedoic acid and placebo (Table 2). Effects on HDL‐C were negligible (<6% change from baseline in both treatment groups).

Figure 3.

Effect of bempedoic acid in patients with statin intolerance: percent change from baseline to week 12 in lipid parameters and biomarkers. Data for low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C), non–high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (non–HDL‐C), total cholesterol (TC), and apolipoprotein B (apoB) are means±standard error. Data are medians for high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP). LDL‐C, non–HDL‐C, TC, and apoB were analyzed using analysis of covariance, with percent change from baseline as the dependent variable, treatment and cardiovascular disease risk category (primary prevention, secondary prevention) as fixed effects, and baseline as a covariate. hsCRP was analyzed using nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. *P<0.001 vs placebo.

Figure 4.

Effect of bempedoic acid in patients with statin intolerance: LDL‐C (low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol), apolipoprotein B, and hsCRP (high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein) from baseline through week 24. Data for (A) LDL‐C and (B) apolipoprotein B are means±standard errors. (C) For hsCRP, data are medians, with error bars indicating Q1 and Q3.

Table 2.

Percent Change From Baseline to Week 24 in Lipid Parameters and Biomarkers

| Parameter | Placebo (n=107) | Bempedoic Acid (n=224) | Difference (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL‐C | −2.3±1.6 | −21.2±1.4 | −18.9 (−23.0, −14.9) | <0.001 |

| Non–HDL‐C | −0.9±1.3 | −18.0±1.2 | −17.1 (−20.5, −13.7) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol | −1.0±1.0 | −15.5±1.0 | −14.5 (−17.2, −11.8) | <0.001 |

| apoB | 0.5±1.3 | −15.0±1.1 | −15.5 (−18.8, −12.2) | <0.001 |

| hsCRP | 4.4 (67.8)a | −25.1 (73.7)a | −27.1 (−40.5, −13.7)b | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides | 7.4±3.5 | 7.9±2.7 | 0.4 (−8.2, 9.0) | 0.921 |

| HDL‐C | −0.6±1.0 | −5.2±1.1 | −4.5 (−7.5, −1.6) | 0.003 |

Data are least‐squares means±standard errors, unless otherwise specified. apoB indicates apolipoprotein B; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Data are medians (interquartile range).

Data are location shifts (asymptotic confidence limits).

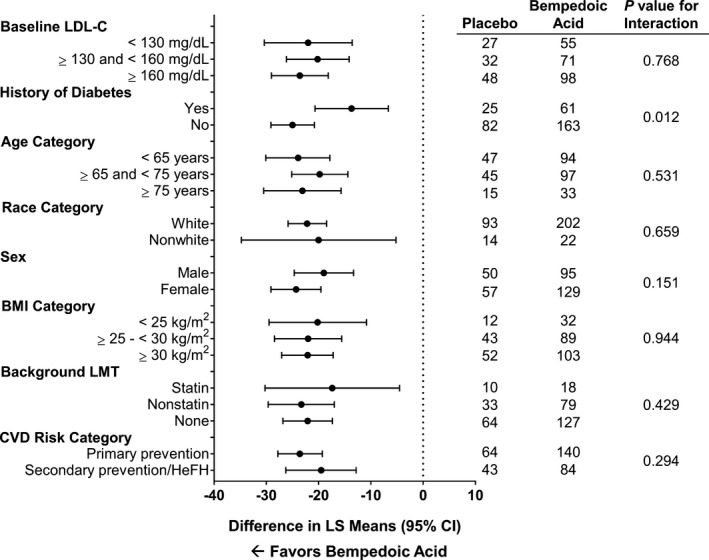

Significant reductions in LDL‐C at week 12 with bempedoic acid versus placebo were observed in all subgroups, including baseline LDL‐C, history of diabetes mellitus, age, race, sex, body mass index, background lipid‐modifying therapy, and cardiovascular disease risk category (P≤0.01; Figure 5). Heterogeneity was statistically significant only in the history of diabetes mellitus subgroup (P value for interaction, 0.012). In addition to the planned subgroup analysis, a post hoc analysis was conducted to analyze LDL‐C percent change from baseline by background lipid‐modifying therapy. Reductions in LDL‐C with bempedoic acid versus placebo were greater among patients receiving no background lipid‐modifying therapy (−22.1% at week 12) or nonstatin background therapy (−23.3%) compared with patients receiving background therapy with a very‐low‐dose statin (−17.4%). In the on‐treatment analysis set, the difference in LDL‐C reduction at week 12 between bempedoic acid (−25.6%) and placebo (−1.7) was −23.9% (95% CI, −27.5% to −20.2%; P<0.001; Table 3). Results of sensitivity analyses for efficacy end points were consistent with the primary analyses.

Figure 5.

Effect of bempedoic acid in patients with statin intolerance: change from baseline to week 12 in LDL‐C by patient subgroup. BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HeFH, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LMT, lipid‐modifying therapy; LS, least‐squares.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses for Efficacy Variables

| LDL‐C (Week 12) | LDL‐C (Week 24) | Non–HDL‐C (Week 12) | TC (Week 12) | apoB (Week 12) | hsCRP (Week 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjunctive LMT analysis | ||||||

| Placebo, n | 107 | 106 | 107 | 107 | 104 | 103 |

| LS mean, % ±SE | −1.2±1.4 | −2.5±1.5 | −0.2±1.1 | −0.7±0.9 | 0.3±1.1 | 2.7 (69.1)a |

| Bempedoic acid, n | 218 | 211 | 218 | 218 | 212 | 212 |

| LS mean, % ±SE | −23.2±1.3 | −22.5±1.4 | −18.9±1.1 | −16.0±0.9 | −15.0±1.1 | −27.6 (60.0)a |

| Difference, % ±SE | −22.0±1.9 | −20.0±2.0 | −18.6±1.6 | −15.3±1.3 | −15.3±1.6 | −25.2 (−36.8, −13.6)b |

| On‐treatment analysis | ||||||

| Placebo, n | 101 | 93 | 101 | 101 | 98 | 97 |

| LS mean, % ±SE | −1.7±1.4 | −1.6±1.6 | −0.4±1.2 | −0.8±1.0 | 0.07±1.2 | 2.7 (60.2)a |

| Bempedoic acid, n | 204 | 173 | 204 | 204 | 200 | 201 |

| LS mean, % ±SE | −25.6±1.3 | −26.5±1.5 | −20.5±1.1 | −17.4±0.9 | −16.8±1.1 | −29.0 (62.2)a |

| Difference, % ±SE | −23.9±1.9 | −24.9±2.1 | −20.1±1.6 | −16.6±1.3 | −16.9±1.6 | −24.4 (−36.3, −12.4)b |

apoB indicates apolipoprotein B; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LMT, lipid‐modifying therapy; LS, least squares; non–HDL‐C, non–high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol.

Medians (interquartile ranges).

Location shift (asymptotic confidence limits).

Safety

Treatment‐emergent adverse events occurred in 64.1% and 56.8% of patients in the bempedoic acid and placebo treatment groups, respectively (Table 4). The majority of adverse events in both groups were mild or moderate in intensity. The most frequent adverse events by system‐organ class were musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (22.2% bempedoic acid, 25.2% placebo), infections and infestations (17.5% bempedoic acid, 22.5% placebo), and gastrointestinal disorders (10.7% bempedoic acid, 11.7% placebo). Serious adverse events were reported by 5.2% of patients (6.0% bempedoic acid, 3.6% placebo), none of which were considered by the investigator to be related to study treatment. More patients in the bempedoic acid treatment group discontinued because of an adverse event (18.4%) compared with placebo (11.7%). Most adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation occurred in only a single patient, and no individual preferred term or system‐organ class drove the higher discontinuation rate in the bempedoic acid group (Table 5). Adverse event rates were similar in patient subgroups.

Table 4.

Treatment‐Emergent Adverse Events

| Parameter | Placebo (n=111) | Bempedoic Acid (n=234) |

|---|---|---|

| Overview of AEs, % (n) | ||

| Any AEs | 56.8 (63) | 64.1 (150) |

| Serious AEs | 3.6 (4) | 6.0 (14) |

| Study‐drug related AEs | 18.0 (20) | 21.8 (51) |

| Discontinuation due to an AE | 11.7 (13) | 18.4 (43) |

| Most common AEs, % (n)a | ||

| Arthralgia | 4.5 (5) | 6.0 (14) |

| Hypertension | 1.8 (2) | 4.3 (10) |

| Fatigue | 6.3 (7) | 3.4 (8) |

| Urinary tract infection | 8.1 (9) | 3.4 (8) |

| Back pain | 3.6 (4) | 3.0 (7) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 3.0 (7) |

| Bronchitis | 5.4 (6) | 2.6 (6) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 0 | 2.1 (5) |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 2.1 (5) |

| Muscle‐related AEs, % (n)b | 16.2 (18) | 12.8 (30) |

| Pain in extremity | 3.6 (4) | 5.6 (13) |

| Myalgia | 7.2 (8) | 4.7 (11) |

| Muscle spasms | 4.5 (5) | 4.3 (10) |

| Muscular weakness | 1.8 (2) | 0.4 (1) |

AE indicates adverse event.

Occurring in ≥2% of patients in either treatment group, excluding muscle‐related AEs (reported below).

Muscle‐related adverse events were predefined as muscular weakness, muscle necrosis, muscle spasms, myalgia, myoglobin blood increased, myoglobin blood present, myoglobin urine present, myoglobinemia, myoglobinuria, myopathy, myopathy toxic, necrotizing myositis, pain in extremity, and rhabdomyolysis.

Table 5.

Adverse Events Leading to Discontinuation by System–Organ Class

| Parameter | Patients, % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=111) | Bempedoic Acid (n=234) | |

| Patients with a TEAE leading to discontinuation | 11.7 (13) | 18.4 (43) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 8.1 (9) | 9.4 (22) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 2.7 (3) | 2.6 (6) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0.9 (1) | 2.1 (5) |

| Nervous system disorders | 1.8 (2) | 1.3 (3) |

| Cardiac disorders | 0 | 1.7 (4) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 0 | 1.3 (3) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 1.3 (3) |

| Investigations | 0 | 0.9 (2) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 0 | 0.9 (2) |

| Infections and infestations | 0.9 (1) | 0.4 (1) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 0.9 (1) | 0.4 (1) |

| Vascular disorders | 0.9 (1) | 0.4 (1) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 | 0.4 (1) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 0.4 (1) |

TEAE indicates, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

No serious muscle‐related adverse events occurred during the study. Predefined muscle‐related adverse events occurred in 12.8% of patients receiving bempedoic acid and 16.2% who received placebo (Table 4). The most common event was myalgia, experienced by 4.7% and 7.2% of patients in the bempedoic acid and placebo treatment groups, respectively. Myalgia led to study drug discontinuation for 3.4% of patients who received bempedoic acid and 6.3% of patients who received placebo. Muscular weakness was reported by 0.4% of bempedoic acid‐treated patients and 1.8% of placebo‐treated patients. No patient had a repeated and confirmed creatine kinase elevation >5 times the upper limit of normal.

New‐onset or worsening diabetes mellitus was less frequently observed in the bempedoic acid treatment group (2.1%) than in the placebo group (4.5%). Among patients with no history of diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL and glycosylated hemoglobin ≥6.5% were less common with bempedoic acid (6.4% and 4.7% of patients, respectively) than placebo (10.6% and 12.9% of patients, respectively). Similar results were observed in patients with diabetes mellitus. Neurocognitive/neurologic events were rare, occurring in 2 patients who received bempedoic acid. Gout was reported by 1.7% of patients in the bempedoic acid group and 0.9% of patients in the placebo group, no cases of which were serious or led to study drug discontinuation.

Four patients, all in the bempedoic acid treatment group, had a single elevated alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase >3 times the upper limit of normal; one of these patients (who was off the study drug for 2 weeks) also had a second value that met this threshold 3 weeks after treatment. No patients met Hy's law criteria. During the course of the study, mean uric acid increased from baseline by 0.68 to 0.86 mg/dL in the bempedoic acid group and decreased by 0 to 0.12 mg/dL in the placebo group. No clinically meaningful changes were observed in other laboratory parameters, vital sign measurements, physical examinations, or ECG findings.

Adjudicated Clinical Events

A positively adjudicated MACE or non‐MACE clinical event occurred in 9 patients in the bempedoic acid group (all had a history of cardiovascular disease) and no patients in the placebo group (Table 6). Seven of the 9 patients had coronary revascularization, 5 of whom had unstable angina and 1 had a nonfatal myocardial infarction; the remaining 2 patients had a nonfatal stroke. No patients had a positively adjudicated cardiovascular death, noncardiovascular death, noncoronary revascularization, or hospitalization for heart failure.

Table 6.

Positively Adjudicated Clinical Events

| Parameter | Patients, % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=111) | Bempedoic Acid (n=234) | |

| Patients with any adjudicated MACE | 0 | 3.8 (9) |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 0 | 0.4 (1) |

| Nonfatal stroke | 0 | 0.9 (2) |

| Hospitalization for unstable angina | 0 | 2.1 (5) |

| Coronary revascularization | 0 | 3.0 (7) |

| Cardiovascular death | 0 | 0 |

| Other adjudicated events | 0 | 0 |

| Noncardiovascular death | 0 | 0 |

| Noncoronary revascularization | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalization for heart failure | 0 | 0 |

MACE indicates major adverse cardiovascular event.

Discussion

The main finding of the CLEAR Serenity trial is that bempedoic acid significantly reduces both LDL‐C and hsCRP compared with placebo and is well tolerated in patients with statin intolerance. Similar to statins, bempedoic acid is an inhibitor of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. It targets an enzyme, ATP‐citrate lyase, upstream of β‐hydroxy β‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A reductase, the target for statins. However, unlike statins, bempedoic acid is a prodrug that is not activated in skeletal muscle.13 The results of the trial demonstrate the potential for bempedoic acid as a novel treatment option for the large number of individuals who have difficulty tolerating statin treatment due to muscle‐related side effects.

Patients with statin intolerance are at increased cardiovascular risk because of ongoing atherogenic lipid elevations.8, 9, 10 Nonstatin alternatives that are currently available, such as bile acid sequestrants, fibrates, and ezetimibe, reduce LDL‐C to a lesser extent than statins and may, therefore, be insufficient alone to adequately lower LDL‐C and mitigate cardiovascular event risk.1, 3, 7 Furthermore, although anti–proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 antibodies have demonstrated large reductions in LDL‐C and a good safety profile in clinical trials, these injectable agents are expensive, are not available everywhere, and their use in countries where they are available is most often restricted to patients with proven familial hypercholesterolemia or coronary artery disease, and thus have had limited uptake in clinical practice.21, 22 Therefore, there is an ongoing need for nonstatin, oral options that can be used alone or as an adjunct to other lipid‐lowering therapies such as ezetimibe.

In the CLEAR Serenity study, bempedoic acid reduced LDL‐C significantly more than placebo in patients with hypercholesterolemia and a history of statin intolerance without inducing side effects commonly attributed to statin treatment. Myalgia and muscular weakness were numerically less frequent with bempedoic acid compared with placebo. Lipid lowering was consistent across patient subgroups and was observed when bempedoic acid was administered as monotherapy or when added to stable background lipid‐modifying therapy. A difference in LDL‐C reduction was observed among patients with a history of diabetes mellitus versus those with no history of diabetes mellitus; however, this was likely attributable to the play of chance in a subgroup analysis with a limited sample size, as LDL‐C reduction with bempedoic acid was comparable in patients with and without diabetes mellitus in previous phase 3 clinical trials.19, 20 Patients in the bempedoic acid treatment group also experienced significant reductions in non–HDL‐C, total cholesterol, apoB, and hsCRP, which were maintained throughout the 24‐week study. CLEAR Serenity expands on the existing body of evidence supporting the effectiveness and favorable safety profile of bempedoic acid for atherogenic lipid reduction in patients with statin intolerance16, 18, 19 by providing longer‐term data in a population meeting defined intolerance criteria and who were receiving treatment as monotherapy or on a background of lipid‐modifying therapy for primary or secondary prevention indications.

Elevations of apoB and hsCRP are associated with increased cardiovascular event risk, whereas on‐treatment reductions or lower achieved levels have been linked to decreased risk.23, 24, 25 The importance of apoB reduction is underscored by epidemiologic and genetic data,26, 27 including a recent Mendelian randomization analysis that determined that the effect of cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibition on cardiovascular event risk correlates with changes in apoB‐containing lipoproteins to a greater degree than changes in LDL‐C or HDL‐C.28 The value of combining LDL‐C lowering with hsCRP reduction is highlighted by results from the JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) study in which the benefit of statin therapy was most pronounced in patients who achieved maximal LDL‐C lowering in combination with reduced hsCRP levels.29 The magnitude of hsCRP reduction with bempedoic acid is marked, ranging from 22.4% to 40.2% for bempedoic acid 180 mg/day.17, 18, 19, 20 In comparison, the addition of ezetimibe to a statin decreases CRP by only 9% to 10%,30, 31 whereas monoclonal antibodies to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 have no impact on CRP levels.32

Bempedoic acid was safe and well tolerated when administered to patients with hypercholesterolemia and a history of statin intolerance. Muscle‐related symptoms were not increased relative to placebo, even among patients who were receiving background therapy with a very‐low‐dose statin. This finding is notable for 2 reasons: >90% of patients enrolled in the study had experienced muscle symptoms during past treatment with a statin, and both bempedoic acid and statins act on the same biochemical pathway. A key differentiator between statins and bempedoic acid is that bempedoic acid is a prodrug that requires activation by very‐long‐chain acyl‐CoA synthetase‐1, an enzyme that is absent in skeletal muscle.13 The trial confirms the expectation that bempedoic acid does not induce muscle‐related side effects. Patients in the bempedoic acid treatment group did experience a small elevation in mean uric acid levels, but the occurrence rate of gout was low (1.7%). Increases in uric acid observed in patients taking bempedoic acid may be attributable to a potential competition between uric acid and the glucuronide metabolite of bempedoic acid for the same renal transporter(s). A small number of adjudicated clinical events occurred in the bempedoic acid treatment group, whereas none were observed in the placebo group. The imbalance between treatment groups is likely due to the small number of events overall and the 2:1 randomization scheme resulting in twice as many patients in the bempedoic acid treatment group. There has been no suggestion from prior studies of increased MACE risk with bempedoic acid. In the CLEAR (Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic acid, an ACL‐Inhibiting Regimen) Harmony study, which enrolled patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and/or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia receiving maximally tolerated statin therapy, the rate of adjudicated MACE over 52 weeks of treatment was 4.6% with bempedoic acid and 5.7% with placebo.20 Further insights regarding the long‐term efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid in patients with statin intolerance will come from the ongoing cardiovascular outcomes trial (CLEAR [Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic acid, an ACL‐Inhibiting Regimen] Outcomes; NCT02993406).

The CLEAR Serenity trial enrolled patients with either a primary or secondary indication for lipid‐lowering therapy, which, if not for demonstrated intolerance, would typically include a statin. The high baseline mean LDL‐C, frequent absence of any lipid‐lowering therapy at baseline, and marked prevalence of cardiometabolic comorbidities reflect both the high cardiovascular risk of this population and the paucity of treatment options for these patients. The CLEAR Serenity study is also notable for the large proportion of women, a group that is often underrepresented in clinical trials of pharmaceutical agents for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.33 The greater percentage of women versus men in the study may be related to the observed increased risk for statin intolerance among women.3, 34 Overall, the enrollment criteria of the study allowed for assessing bempedoic acid in the diversity of patients and background therapies that are encountered in clinical practice.

The efficacy and safety data presented herein must be interpreted with an understanding of the study's limitations, such as its comparatively short duration (24 weeks). The durability of effect and safety of extended bempedoic acid use is currently being evaluated in a long‐term, open‐label extension study, during which all patients will receive bempedoic acid for up to 78 weeks.

The results from the CLEAR Serenity study demonstrate that bempedoic acid significantly reduces LDL‐C and hsCRP in patients with statin intolerance, regardless of baseline LDL‐C or concomitant lipid‐lowering therapy. Treatment with bempedoic acid was well tolerated and was not associated with an increased risk for muscle‐related adverse events. These findings show that bempedoic acid offers an oral therapeutic alternative that lowers LDL‐C and is complementary to statins and other nonstatin therapies.

Sources of Funding

This clinical trial was funded by Esperion Therapeutics, Inc. Medical writing/editorial support for preparation of this article was also provided to JB Ashtin by Esperion Therapeutics, Inc.

Disclosures

Laufs has served as a consultant for Amgen, Esperion, and Sanofi. Banach has received research grant(s)/support from Sanofi and Valeant, and has served as a consultant for Abbott/Mylan, Abbott Vascular, Actavis, Akcea, Amgen, Biofarm, KRKA, MSD, Sanofi‐Aventis, Servier, Valeant, Daichii Sankyo, Esperion, Lilly, and Resverlogix. Mancini received research grant(s)/support from Merck, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has served as a consultant for these companies as well as Esperion, Novartis, and Servier. Gaudet has served as a consultant for Aegerion Pharmaceuticals (Novelion Therapeutics), Amgen, Akcea, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, CymaBay Therapeutics, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Esperion, GlaxoSmithKline, Gemphire Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi. Bloedon and Kelly are full‐time employees of Esperion. Sterling is a former employee of Esperion. Stroes has received research grant(s)/support to his institution from Amgen, Sanofi, Resverlogix, and Athera, and has served as a consultant for Amgen, Sanofi, Esperion, Novartis, and Ionis Pharmaceuticals.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supplemental Methods

Acknowledgments

The authors offer their appreciation to all the investigators, study site staff, and patient volunteers who participated in the study. They also thank IQVIA for their oversight of patient randomization, clinical laboratory services, statistical analyses, clinical monitoring, data management, and clinical programming. The authors thank Crystal Murcia, PhD, and Lamara D. Shrode, PhD, CMPP, of JB Ashtin, who developed the first draft of the manuscript based on an author‐approved outline and assisted in implementing revisions based on the authors’ input and direction throughout the editorial process.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011662 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011662.)

References

- 1. Mancini GB, Baker S, Bergeron J, Fitchett D, Frohlich J, Genest J, Gupta M, Hegele RA, Ng D, Pearson GJ, Pope J, Tashakkor AY. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: Canadian Consensus Working Group update (2016). Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:S35–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenson RS, Baker S, Banach M, Borow KM, Braun LT, Bruckert E, Brunham LR, Catapano AL, Elam MB, Mancini GBJ, Moriarty PM, Morris PB, Muntner P, Ray KK, Stroes ES, Taylor BA, Taylor VH, Watts GF, Thompson PD. Optimizing cholesterol treatment in patients with muscle complaints. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1290–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, Vladutiu GD, Raal FJ, Ray KK, Roden M, Stein E, Tokgozoglu L, Nordestgaard BG, Bruckert E, De Backer G, Krauss RM, Laufs U, Santos RD, Hegele RA, Hovingh GK, Leiter LA, Mach F, Marz W, Newman CB, Wiklund O, Jacobson TA, Catapano AL, Chapman MJ, Ginsberg HN; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus P. Statin‐associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy‐European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J. 2015; 36:1012–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lakey WC, Greyshock NG, Kelley CE, Siddiqui MA, Ahmad U, Lokhnygina YV, Guyton JR. Statin intolerance in a referral lipid clinic. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:870–879.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): an internet‐based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banach M, Stulc T, Dent R, Toth PP. Statin non‐adherence and residual cardiovascular risk: there is need for substantial improvement. Int J Cardiol. 2016;225:184–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laufs U, Filipiak KJ, Gouni‐Berthold I, Catapano AL; SAMS Expert Working Group . Practical aspects in the management of statin‐associated muscle symptoms (SAMS). Atheroscler Suppl. 2017;26:45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Graham JH, Sanchez RJ, Saseen JJ, Mallya UG, Panaccio MP, Evans MA. Clinical and economic consequences of statin intolerance in the United States: results from an integrated health system. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11:70–79. e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Serban MC, Colantonio LD, Manthripragada AD, Monda KL, Bittner VA, Banach M, Chen L, Huang L, Dent R, Kent ST, Muntner P, Rosenson RS. Statin intolerance and risk of coronary heart events and all‐cause mortality following myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1386–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harrison TN, Hsu JY, Rosenson RS, Levitan EB, Muntner P, Cheetham TC, Wei R, Scott RD, Reynolds K. Unmet patient need in statin intolerance: the clinical characteristics and management. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2018;32:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, Birtcher KK, Daly DD Jr, DePalma SM, Minissian MB, Orringer CE, Smith SC Jr. 2017 focused update of the 2016 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of non‐statin therapies for LDL‐cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1785–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toth PP, Patti AM, Giglio RV, Nikolic D, Castellino G, Rizzo M, Banach M. Management of statin intolerance in 2018: still more questions than answers. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018;18:157–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pinkosky SL, Newton RS, Day EA, Ford RJ, Lhotak S, Austin RC, Birch CM, Smith BK, Filippov S, Groot PH, Steinberg GR, Lalwani ND. Liver‐specific ATP‐citrate lyase inhibition by bempedoic acid decreases LDL‐C and attenuates atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ballantyne CM, Davidson MH, Macdougall DE, Bays HE, Dicarlo LA, Rosenberg NL, Margulies J, Newton RS. Efficacy and safety of a novel dual modulator of adenosine triphosphate‐citrate lyase and adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase in patients with hypercholesterolemia: results of a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1154–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gutierrez MJ, Rosenberg NL, Macdougall DE, Hanselman JC, Margulies JR, Strange P, Milad MA, McBride SJ, Newton RS. Efficacy and safety of ETC.‐1002, a novel investigational low‐density lipoprotein‐cholesterol‐lowering therapy for the treatment of patients with hypercholesterolemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thompson PD, Rubino J, Janik MJ, MacDougall DE, McBride SJ, Margulies JR, Newton RS. Use of ETC.‐1002 to treat hypercholesterolemia in patients with statin intolerance. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9:295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ballantyne CM, McKenney JM, MacDougall DE, Margulies JR, Robinson PL, Hanselman JC, Lalwani ND. Effect of ETC‐1002 on serum low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic patients receiving statin therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1928–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thompson PD, MacDougall DE, Newton RS, Margulies JR, Hanselman JC, Orloff DG, McKenney JM, Ballantyne CM. Treatment with ETC‐1002 alone and in combination with ezetimibe lowers LDL cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic patients with or without statin intolerance. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:556–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ballantyne CM, Banach M, Mancini GBJ, Lepor NE, Hanselman JC, Zhao X, Leiter LA. Efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid added to ezetimibe in statin‐intolerant patients with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ray KK, Bays HE, Catapano AL, Lalwani ND, Bloeden LT, Sterling L, Ballantyne CM. CLEAR Harmony—long‐term safety, tolerability and efficacy of bempedoic acid vs. placebo in high cardiovascular risk patients with LDL‐C above 1.8 mmol/L on maximally tolerated statin therapy. Paper presented at: European Society of Cardiology Congress 2018; Munich, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohen JD, Cziraky MJ, Jacobson TA, Maki KC, Karalis DG. Barriers to PCSK9 inhibitor prescriptions for patients with high cardiovascular risk: results of a healthcare provider survey conducted by the National Lipid Association. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11:891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Virani SS, Kennedy KF, Akeroyd JM, Morris PB, Bittner VA, Masoudi FA, Stone NJ, Petersen LA, Ballantyne CM. Variation in lipid‐lowering therapy use in patients with low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥190 mg/dl: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry‐Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Mora S, Pedersen TR, LaRosa JC, Nestel PJ, Simes RJ, Durrington P, Hitman GA, Welch KM, DeMicco DA, Zwinderman AH, Clearfield MB, Downs JR, Tonkin AM, Colhoun HM, Gotto AM Jr, Ridker PM, Kastelein JJ. Association of LDL cholesterol, non‐HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B levels with risk of cardiovascular events among patients treated with statins: a meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2012;307:1302–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Holten TC, Waanders LF, de Groot PG, Vissers J, Hoefer IE, Pasterkamp G, Prins MW, Roest M. Circulating biomarkers for predicting cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review and comprehensive overview of meta‐analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bohula EA, Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, Zhou J, Murphy SA, White JA, Tershakovec AM, Blazing MA, Braunwald E. Achievement of dual low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein targets more frequent with the addition of ezetimibe to simvastatin and associated with better outcomes in IMPROVE‐IT. Circulation. 2015;132:1224–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Zdrojewski T, Williams K, Thanassoulis G, Furberg CD, Peterson ED, Vasan RS, Sniderman AD. Apolipoprotein B improves risk assessment of future coronary heart disease in the Framingham Heart Study beyond LDL‐C and non‐HDL‐C. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robinson JG, Williams KJ, Gidding S, Boren J, Tabas I, Fisher EA, Packard C, Pencina M, Fayad ZA, Mani V, Rye KA, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg‐Hansen A, Douglas PS, Nicholls SJ, Pagidipati N, Sniderman A. Eradicating the burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by lowering apolipoprotein B lipoproteins earlier in life. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009778 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ference BA, Kastelein JJP, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, Nicholls SJ, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Laufs U, Brook RD, Oliver‐Williams C, Butterworth AS, Danesh J, Smith GD, Catapano AL, Sabatine MS. Association of genetic variants related to CETP inhibitors and statins with lipoprotein levels and cardiovascular risk. JAMA. 2017;318:947–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM Jr, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, Macfadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT, Glynn RJ; JUPITER Trial Study Group . Reduction in C‐reactive protein and LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular event rates after initiation of rosuvastatin: a prospective study of the JUPITER trial. Lancet. 2009; 373:1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pearson TA, Ballantyne CM, Veltri E, Shah A, Bird S, Lin J, Rosenberg E, Tershakovec AM. Pooled analyses of effects on C‐reactive protein and low density lipoprotein cholesterol in placebo‐controlled trials of ezetimibe monotherapy or ezetimibe added to baseline statin therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morrone D, Weintraub WS, Toth PP, Hanson ME, Lowe RS, Lin J, Shah AK, Tershakovec AM. Lipid‐altering efficacy of ezetimibe plus statin and statin monotherapy and identification of factors associated with treatment response: a pooled analysis of over 21,000 subjects from 27 clinical trials. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223:251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sahebkar A, Di Giosia P, Stamerra CA, Grassi D, Pedone C, Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Ferri C, Giorgini P. Effect of monoclonal antibodies to PCSK9 on high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein levels: a meta‐analysis of 16 randomized controlled treatment arms. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81:1175–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scott PE, Unger EF, Jenkins MR, Southworth MR, McDowell TY, Geller RJ, Elahi M, Temple RJ, Woodcock J. Participation of women in clinical trials supporting FDA approval of cardiovascular drugs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1960–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karalis DG, Wild RA, Maki KC, Gaskins R, Jacobson TA, Sponseller CA, Cohen JD. Gender differences in side effects and attitudes regarding statin use in the Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE) study. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:833–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplemental Methods