ABSTRACT

Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide have always been the subject of intense debate across society. In 2006 and in 2014, the Royal College of Physicians surveyed its members for their opinions on the subject. The results of these surveys are summarised here.

KEYWORDS: Euthanasia, physician-assisted dying, physician-assisted suicide, survey, WORK FORCE

Physician-assisted dying in the UK: background, terminology and legality

Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide (PAS) have been the subject of intense debate since time immemorial.1 The fiercely emotive issue may feel exceedingly complex to some while remaining desperately simple to others, resulting in extensive of discussion at all levels of society. From heated discourse over family dinners to formal deliberation and examination by Oxbridge scholars, the moral questions surrounding end-of-life care (EoLC) continue to be at the forefront of medical ethics. Each individual will have a unique view on euthanasia and PAS, created through a combination of religious beliefs (or lack thereof), cultural background, upbringing and experience. Despite this, we, as citizens of the United Kingdom (UK), all have a duty and responsibility to act within the law where both euthanasia and PAS are currently illegal (see Box 1).

Box 1.

|

Physician-assisted dying (PAD) is the overarching term, encompassing both euthanasia and PAS, which describes physician involvement in the intentional termination of a patient’s life. The fundamental difference between euthanasia and PAS is the degree of physician involvement.

The House of Lords Select Committee on Medical Ethics defines euthanasia as ‘a deliberate intervention undertaken with the express intention of ending a life’.

Euthanasia can be further subclassified into voluntary and involuntary where voluntary euthanasia occurs as a result of an informed request from a mentally competent patient to end their life while involuntary euthanasia can occur at a physician’s discretion without the patient’s informed consent. Furthermore, ethicists may also describe euthanasia as active or passive where active euthanasia is a positive action that leads to death, ie killing the patient, compared with passive euthanasia where inaction through omitting treatment to prolong life results in death. Many ethicists argue that passive euthanasia is a contradiction in terms as purposeful action does not directly cause death and therefore is not a form of euthanasia at all. For the purposes of this article we refer to euthanasia in its active voluntary form.

The Canadian Medical Association defined PAS as:

knowingly and intentionally providing a person with the knowledge or means or both required to commit suicide, including counselling about lethal doses of drugs, prescribing such lethal doses or supplying the drugs

Remembering the physician in physician-assisted dying

Death and EoLC can be difficult for many physicians. Some physicians feel that death is synonymous with failure, but with the expansion of palliative care there is a move toward accepting the inevitable and stopping futile attempts at prolonging life. With this acceptance comes the knowledge that physicians can actively help to make a patient’s last days free from pain, free from anxiety, spiritually rewarding and (here lies the dilemma) shorter. The line between active involvement in death and the active alleviation of suffering can be thin and blurred. This could not be better illustrated than by the ‘doctrine of double effect’: where the administration of medication may shorten life, but this is not the primary reason for doing so; the primary reason usually being pain relief or relief from agitation or anxiety. The guiding principle of ‘first, do no harm’ underpins the aversion to intentional killing, yet most physicians still accept the doctrine of double effect as part of good palliative care, contrarily due to the same underlying principle. The argument for PAD is undoubtedly across this blurred line as the resultant death is a direct consequence of the physician’s actions with no goal other than to end life, thereby relieving suffering (not vice versa).

However, the question is not solely a moral and ethical one. It clearly has practical implications too; if, hypothetically, euthanasia and/or PAS were to be made legal it would fall to physicians to enable these acts through prescription, action or both. It is therefore vital that the medical profession, both at the individual and governing body level, is integrally involved in the discussion. Recognising this, the Royal College of Physicians’ (RCP) Council determined to consult with its members on these issues to decide how to position itself in the debate.

The RCP asks its members for their views

The RCP carried out two surveys to gauge the views of its members and fellows on PAD. The first survey in 2006 was as a result of Lord Joffe’s Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill and the second survey in 2014 was as a result of Lord Falconer of Thornton’s bill of the same name.

The 2006 survey – should the law be changed to allow PAS?

Between 2003 and 2006 three attempts were made by Lord Joffe to introduce a bill that would legalise assisted dying into the House of Lords. Interrupted by the dissolution of parliament for the 2005 general election, it was finally rejected by 148 votes to 100. The bill outlined measures that would allow doctors to give terminally ill patients a fatal dose of medication to self-administer, ie PAS; it did not advocate for euthanasia.

The question was being asked in parliament so the RCP endeavoured to understand the views of its members and asked whether or not the law should be changed. A survey was sent to approximately 16,000 members, with 5,111 responding (around 30%).

The survey asked respondents to consider the following key statement (the moral or ethical dilemma):

‘(We) believe that with improvements in palliative care, good clinical care can be provided within existing legislation, and that patients can die with dignity. A change in legislation is not needed.’ Do you agree?

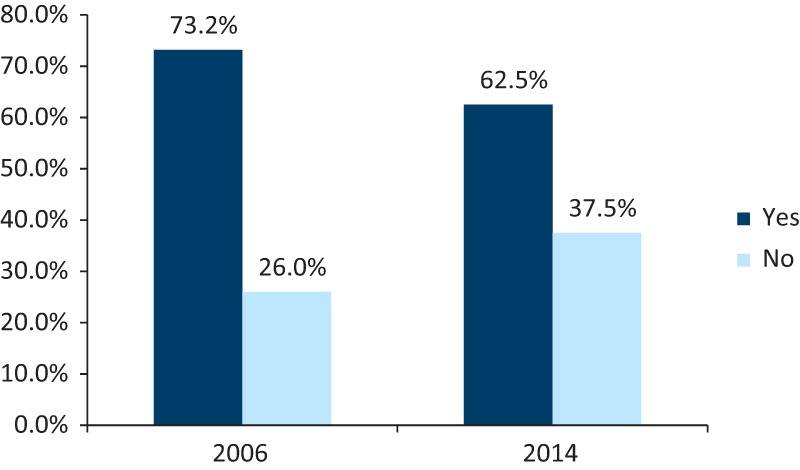

The large majority of respondents, 3,741 people (73.2%), answered that a change in legislation was not needed, leaving a minority of 26% supporting a change in the law.

The survey went on to ask members to consider the next key statement (the practical dilemma):

Regardless of your support or opposition to change, in the event of legislation receiving royal assent, would you personally be prepared to participate actively in a process to enable a patient to terminate his or her own life?

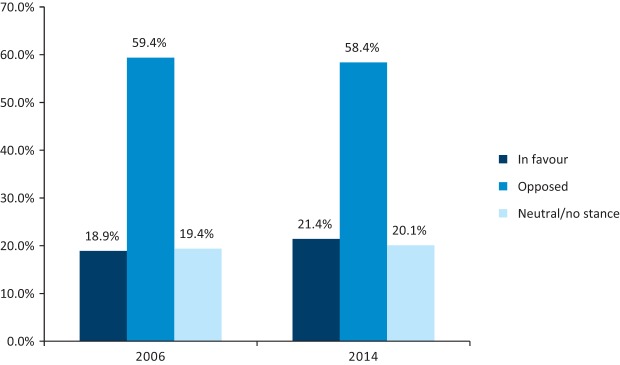

In contrast to the first question, only 59.4% answered no, while 18.9% said they would actively participate in PAS, leaving 19.4% uncertain.

As a result of the 2006 survey, the RCP indicated its opposition to the bill and did not advocate for a change in the law. Instead, the RCP called for a campaign for better EoLC within existing legislation.

The 2014 survey – should the law be changed to allow PAD including euthanasia?

In 2010 Lord Falconer chaired the Commission on Assisted Dying (COAD) to determine whether the approach to changing the law was effective and to examine under which circumstances PAD should be allowed within UK law. The Commission published its final report in 2012, which proposed that doctors would hold a prominent role in the new framework for assisted dying. This was brought before the House of Lords by Lord Falconer in 2014 in the Assisted Dying Bill. It stated that patients with a life expectancy of less than six months with an informed and voluntary settled intention to end their life (and deemed to have capacity in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005) could receive physician assistance to die. This should be confirmed by two doctors. A number of amendments were suggested, including a move to assisted suicide as opposed to assisted dying and the involvement of the High Court in each decision, but the bill underwent a number of defeats before finally failing due to parliament dissolution for the 2015 general election. A very similar bill was proposed in Scotland between 2009 and 2015. Scottish National Party Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) Margo MacDonald proposed the End of Life Assistance (Scotland) Bill followed by the Assisted Suicide (Scotland) Bill in which it was stated that doctors helping patients to end their life under certain conditions were not guilty of a crime.

As these bills had yet again been proposed in parliament, the RCP Council felt it needed to again elicit the views of its members and fellows. A survey was sent to members and accompanied by a consultation document which outlined the context of the discussion, defined terminology and signposted members to external resources. The survey was sent to 21,674 members, with 8,767 responding (40%).

As in the 2006 survey, members were asked to respond to the following key statement:

‘(We) believe that with improvements in palliative care, good clinical care can be provided within existing legislation, and that patients can die with dignity. A change in legislation is not needed.’ Do you agree?

The majority of respondents, 4,179 people (62.5%), answered that a change in legislation was not needed, leaving a minority of 2,507 (37.5%) supporting a change in the law.

This time, the survey also asked:

Do you support a change in the law to permit assisted suicide by the terminally ill with the assistance of doctors?

The majority of respondents, 3,858 people (58%), said no, compared with 2,168 people (32%) who said yes. A further 10% answered yes, but not by doctors.

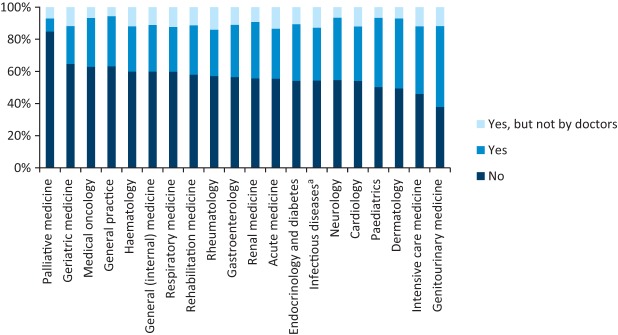

Interestingly, the specialties with more involvement in EoLC eg palliative medicine, geriatric and general medicine, oncology, etc, had the largest proportion of responders objecting to a move toward PAD. Fig 1 shows the breakdown of responses by specialties with more than 80 responses. The largest proportion of physicians saying ‘no’ came from palliative medicine (85%, 415 responses), with the smallest from genitourinary medicine physicians (38%, 119 responses).

Fig 1.

Responses broken down by specialty to the question ‘Do you support a change in the law to permit assisted suicide by the terminally ill with the assistance of doctors?’ aInfectious diseases and tropical medicine

Unlike the original survey, the 2014 survey asked members how they felt the RCP should position itself in the debate:

What should the College’s position be on ‘assisted dying’ as defined in the RCP’s consultation document?

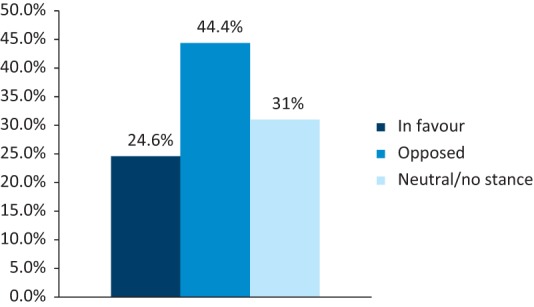

Of the members who answered this question, 6,697 respondents (44.4%) felt the RCP should be opposed to a change in legislation, compared with 24.6% in favour of supporting change; notably 31% felt the RCP should remain neutral / take no stance. Fig 2 illustrates the breakdown of responses.

Fig 2.

How should the Royal College of Physicians position itself on the issue of assisted dying?

The RCP Council has reassured members that regardless of the RCP’s position, individual members are entitled to take a position of their own and express their personal views on assisted dying.

Similar to the 2006 survey, members were asked the same final question:

Regardless of your support or opposition to change, in the event of legislation receiving royal assent, would you personally be prepared to participate actively in assisted dying?

This elicited a similar response to the 2006 survey: 58.4% answered that they were opposed, 21.4% were in favour of actively participating, and 20.1% were neutral/uncertain.

A comparison between the 2006 and 2014 surveys: a shift in opinion?

The results of both surveys showed that the majority of respondents did not support a change in the law on assisted dying; however, the number objecting to a change in legislation fell in 2014 by 10.7% from 73.2% to 62.5% (Fig 3), possibly indicating a shift in opinion.

Fig 3.

Comparison of 2006 and 2014 responses to the statement: ‘(We) believe that with improvements in palliative care, good clinical care can be provided within existing legislation, and that patients can die with dignity. A change in legislation is not needed. Do you agree?’

Although a much smaller change, these results also showed an increase of 2.5% in the number of physicians in favour of being actively involved in PAD, with a decrease of 1% in members opposed to taking part (Fig 4).

Fig 4.

Comparison of 2006 and 2014 responses to whether, in the event of legislation receiving royal assent, physicians would personally be prepared to participate actively in assisted dying.

Discussion

Physician-assisted dying is an area of continued political and professional debate both in the UK and abroad. While PAD remains illegal in the UK, the past 2 decades have seen legislative changes permitting euthanasia and assisted suicide in the Netherlands (Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act 2001), Belgium (Belgian Act on Euthanasia 2002) and Luxembourg (Law on the Right to Die with Dignity 2009). Many of the changes are modeled on the Death with Dignity Act passed in Oregon, USA in 1994; similar laws have been passed in the states of Washington, Vermont and, most recently, California. Columbia and Canada have similar legislation. Perhaps the most well-known country associated with PAD is Switzerland, where, surprisingly, there is no specific legislation on PAD protocol except to say that assisted suicide is legal in the absence of selfish motives under s.115 of the Swiss Criminal Code; it is organised by ‘right-to-die’ societies such as Exit or Dignitas.

Following the bills by Lord Joffe and Lord Falconer, and after the two RCP surveys, there was one further attempt to introduce the Assisted Dying Bill in the UK, this time into the House of Commons in 2015. It was overwhelmingly rejected by 330 votes to 118.

Within the UK there have been a number of large-scale academic studies exploring the attitudes of doctors toward PAD. A systematic review published by McCormack et al in 2010 analysed the findings of 15 studies published between 1990 and 2010 and found that broadly doctors do not support a change in legislation in favour of either active voluntary euthanasia or PAS,2 in keeping with the findings of the RCP surveys. Also in line with the surveys carried out by the RCP, McCormack et al found that only a minority of doctors would be willing to actively participate in either active voluntary euthanasia or PAS.

Although physicians are opposed to a change in legislation, this interestingly does not mirror the views of the general population in the UK. Seale (2009) directly compared the attitudes of the general public with those of doctors and found that the general public were generally in favour of a change in legislation.3 This leads to questions as to whether the difference is due to the proximity of physicians to life-and-death scenarios compared with the general population, or whether the training itself to heal and do no harm precludes the ability withdraw life. These philosophical and ethical dilemmas are intriguing and warrant further exploration, but are beyond the scope of this paper. The argument for proximity is borne out by other studies showing a statistically significant association between regularly working with dying patients and objection to PAD. What is clear, however, is that should PAD ever become legal in any form it is the doctors who will be relied upon and must bear the responsibility of implementing life-ending treatments and therefore their views must be considered central to the ongoing debate.

It is very likely that this subject will be revisited in the future with further bills being introduced into parliament and doctors’ views again elicited. If the trend shown by these two surveys continues, then it is possible that doctors may come to support a change in legislation over the course of time. We must learn from countries and American states that have already adopted the change. It is vital that we continue to discuss and imagine what such a change may look like in the UK. It will always be difficult to define unbearable suffering, given the variation in what different individuals can withstand; the basic difference yet complete co dependence of physical and psychological suffering makes the line even harder to draw. Should these definitions be resolved, it remains unclear who would be involved in the decisions for PAD: the number of physicians needed; whether the High Court or the coroner will be involved; ways to resolve and legislate disagreements between family members; whether this will affect the grieving process; and how vulnerable individuals will be protected. Unless each and every element and concern are addressed, it will be difficult to protect our patients and our society from the so-called slippery slope to illegal, and more importantly, immoral taking of life without cause or justification.

In addition to protecting patients, many doctors will also feel the need for protection. There are many factors that influence and individual’s stance on PAD, religion being the most influential. Most envision a scenario where doctors would have the option to ‘opt out’ if the legislation were changed to protect doctors who feel PAD is morally wrong. If ‘opt out’ were not adopted it could influence the type of person applying to medical school and actively deter some individuals, irrevocably changing the landscape of the medical profession, especially if we again consider the power of culture and religion in these debates.

The RCP shares its stance of opposition to PAD with other formal bodies including, but not limited to, the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP),4 the Association of Palliative Medicine (APM)5 and, disregarding a small period of neutrality, the British Medical Association (BMA).6 The RCP recognises the variation in individual members’ opinions, based on their own cultural, spiritual, religious and personal experiences.

Conclusion

Despite a number of bills and high-profile court cases in support of assisted dying, it continues to be an offence under UK law. In both 2006 and 2014, the majority of RCP members and fellows opposed a change in current legislation on assisted dying and favoured improvements in palliative care. Therefore, the RCP opposes any change in current legislation surrounding PAD and maintains that good palliative and end-of-life care is the mainstay in providing patients with a good and dignified death.

Note

The consultation document sent to members along with the 2014 survey is available to download at www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/rcp-reaffirms-position-against-assisted-dying

References

- 1.Harris NM. The euthanasia debate. J R Army Med Corps 2001;147:367–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack R, Clifford M, Conroy M. Attitudes of UK doctors towards euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 2012;26:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seale C. Legalisation of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: survey of doctors’ attitudes. Palliat Med 2009;23:205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of General Practitioners Assisted Dying Consultation Analysis. RCGP, 2014. Available online at: www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/~/media/Files/Policy/Assisted-Dying-Consultation/Assisted%20Dying%20 Consultation%20Analysis.ashx [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain Survey on Assisted Suicide 2015. APM, 2015. Available online at: http://217.199.187.67/apmonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/APM-survey-on-Assisted-Suicide-website.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.British Medical Association End of life care and physician assisted dying. London: BMA, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]