Abstract

We present a novel treatment with the use of intraventricular antibiotics delivered through a ventriculostomy in a patient who developed septic cavernous sinus thrombosis after sinus surgery. A 65-year-old woman presented with acute on chronic sinusitis. The patient underwent a diagnostic left maxillary antrostomy, ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy and sinusotomy. Postoperatively, the patient experienced altered mental status with episodic fever despite treatment with broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. MRI of the brain showed extensive meningeal enhancement with the involvement of the right trigeminal and abducens nerve along with thick enhancement along the right pons and midbrain. MR arteriogram revealed a large filling defect within the cavernous sinus. Intraventricular gentamicin was administered via external ventricular drain (ie, ventriculostomy) every 24 hours for 14 days with continued treatment of intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole. The patient improved with complete resolution of her cavernous sinus meningitis on repeat brain imaging at 6 months posthospitalisation.

Keywords: neurosurgery; drug therapy related to surgery; ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology; meningitis; infection (neurology)

Background

Acute sinusitis is a common infection seen by primary care physicians in as many as 40 per 1000 patients and it is the second most common infectious disease seen by general practitioners.1 Most cases of sinusitis are caused by the same pathogens that cause an upper respiratory infection with the majority being viral in nature. However, a more serious disease course may ensue with bacterial or fungal infections. Although rare, the infection may extend from the sphenoidal or ethmoidal sinuses to the intracranial cavity, endangering the adjacent intracranial region including the cavernous sinus. This has the potential to cause acute fulminant meningitis and possibly a highly lethal septic thrombosis.2

Case presentation

The patient is a 65-year-old African-American woman. She presented to the emergency department complaining of a cough, fever, sore throat, purulent nasal discharge, loss of appetite, neck stiffness with the decreased rotational range of motion and weight loss for the prior 2 weeks. The family noted that she was becoming lethargic and somnolent. The patient described episodes of transient blurry vision accompanied by binocular double vision, lasting hours with spontaneous resolution. Significant medical history included chronic sinusitis and asthma. She denied recent sick contacts, travel, animal or insect bites. Physical examination on initial presentation was unremarkable and she was neurologically intact. Her initial vital signs and lab work were significant for sinus tachycardia (142 BPM), low-grade fever (100.2°F) and significant leukocytosis (31 560/μL with 88% neutrophils) consistent with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).

Blood cultures obtained on presentation grew Eikenella corrodens and Streptococcus anginosus with no documented resistance on sensitivity assessment. Acute on chronic sinusitis was considered as the source for her SIRS. A radiological investigation with CT of the brain and sinuses was performed which demonstrated no acute intracranial abnormality. However, there was opacification in the left sphenoid and posterior ethmoid air sinuses consistent with acute sinusitis. An admitting diagnosis of sepsis secondary to acute on chronic sinusitis was made. The patient was admitted to the hospital under the general medical service and started on empiric intravenous antimicrobial therapy with ceftriaxone, vancomycin and metronidazole. Consultations by the infectious disease and otorhinolaryngology (ear, nose and throat [ENT]) teams were requested.

Treatment

On days 2 and 3 of her hospitalisation, the patient continued to experience fever, with a maximum temperature of 102.0°F (38.9°C). Her level of consciousness declined to persistent somnolence but still able to complain of neck tenderness, photophobia and recurrent diplopia. On examination, she had mild periorbital oedema, tenderness to the right preauricular and submandibular regions and worsening nuchal rigidity. Acute meningitis was suspected and ceftriaxone dosage was increased from 1 to 2 g every 12 hours. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (table 1) strongly suggested acute bacterial meningitis. Given the patient’s diplopia, MRI of the brain and sinuses with and without contrast along with MR arteriogram (MRA) and venogram (MRV) were performed. Non-specific dural enhancement was noted along with bilateral non-specific nasal sinus opacification. Her MRV revealed a small opacification in the cavernous sinus and attenuation of the cavernous internal carotid artery; therefore, a diagnosis of septic cavernous sinus thrombosis (SCST) was made.

Table 1.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Completed on hospital days 2 and 14

| CSF parameters | Hospital day 2 | Hospital day 14 |

| Appearance | Slight xanthochromia colour with hazy appearance | No xanthochromia |

| Protein (mg/dL) | 206.9 | 9.9 |

| Glucose (CSF) (mg/dL) | 15 | 86 |

| Glucose (serum) | 98 mg/dL | Not recorded |

| RBC count | 0.0029×1012/L | 0.003×1012/L |

| WBC count | 0.96×109/L | 0.008×109/L |

| Other | PMN 93%, lymphocyte 2%, monocyte 5% and no other WBC types were identified. Herpes simplex virus PCR, varicella zoster virus PCR, West Nile virus RNA, HIV, cultures and Gram stain were unremarkable | PMN 93% |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

On day 4 of her hospitalisation, the patient underwent a left endoscopic maxillary antrostomy, left total ethmoidectomy, left sphenoidotomy and left frontal sinusotomy. Intraoperative cultures and tissue biopsy from the left sphenoid sinus grew beta-haemolytic Streptococci species not of groups A, B, C, D, F or G. Postoperatively, the patient continued to have episodic fever despite intravenous antibiotic treatment. Moreover, she continued to complain of persistent diplopia without associated neurological findings and there was no significant improvement in her mentation.

The patient remained persistently somnolent and confused for over a week after her second sinus surgery. She also continued to complain of diplopia without evidence of ophthalmoplegia on neurological examination. Her episodic fevers resolved with acetaminophen. On day 14 of her hospitalisation, repeated CSF analysis (table 1) revealed an improvement in her CSF protein, glucose and white blood cell count.

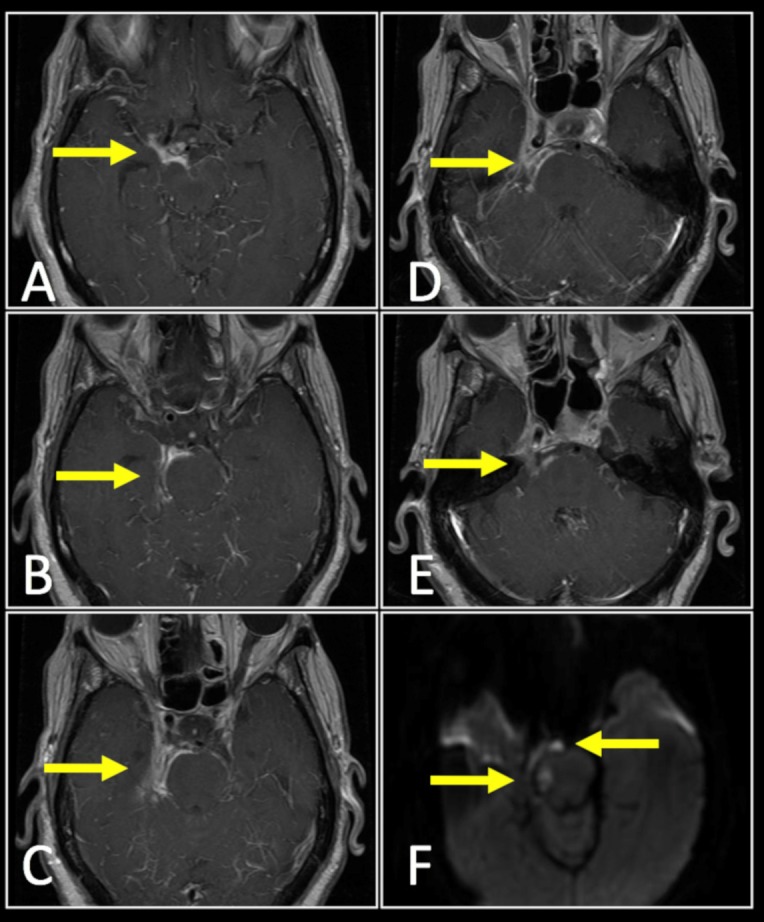

The following day, despite an improved CSF profile, she remained febrile and her mentation was more lethargic. A repeat brain MRI, MRA and MRV was performed. Compared with previous imaging, the MRI demonstrated significantly worse meningeal enhancement adjacent to the anterolateral border of the midbrain, pontine tegmentum and circumferential involvement around the cavernous and supraclinoid carotid artery (figure 1). There was also enhancement along the cavernous portions of the right trigeminal and abducens nerves, likely explaining her persistent complaints of diplopia. Diffusion weighted imaging demonstrated areas of restricted diffusion and abscess formation centred in the region of the right ambient and interpeduncular cisterns. Furthermore, MRA/MRV demonstrated a filling defect in the posterior aspect of the right cavernous sinus consistent with a cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Figure 1.

Cavernous sinus meningitis (below) with associated cavernous sinus thrombosis (not shown). T1-weighted contrast enhanced MRI of the brain revealed extensive meningeal enhancement (arrows) adjacent to the anterolateral border of the midbrain (A), pontine tegmentum (B–E), with circumferential involvement around the cavernous and supraclinoid carotid artery. There is involvement along the right trigeminal and abducens nerves. Diffusion weighted imaging demonstrated areas of restricted diffusion (F) suggestive of abscess formation centred in the region of the right ambient and interpeduncular cisterns.

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for further monitoring and the family was counselled about her critical condition with a potentially grave prognosis. A neurosurgical evaluation was requested.

To guide further treatment, we did a literature review. We did not find any evidence-based treatment options for complicated acute sinusitis, meningitis with abscess and an associated septic intracranial thrombus. A multidisciplinary discussion involving the neurosurgery, ENT, infectious disease and critical care teams took place to determine the best treatment options. Given the lack of response to the standard treatment of intravenous antibiotics and sinus debridements, the feasibility of further debridement through a craniotomy was explored. However, given the intense inflammation in the ventrolateral brainstem along with the potential of devastating injury to adjacent critical neural and vascular structures around the cavernous sinus, a craniotomy was not considered a safe option.

A final decision was made to administer intraventricular antibiotics for ‘local’ antimicrobial therapy as a salvage option. We counselled the family regarding the inherent risks associated with the placement of an indwelling intracranial catheter in the setting of infection and the family consented to surgical treatment. The neurosurgery team cannulated the right frontal horn of the lateral ventricle at the bedside and placed an external ventricular drain (EVD) on day 16 of her hospitalisation to deliver the intraventricular antibiotics. Once a follow-up head CT revealed no new intracranial haemorrhage related to the EVD placement, gentamicin 5 mg was administered with sterile precautions via an intraventricular route every 24 hours for 14 days. This was administered in conjunction with continued systemic intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Despite persistent lethargy, her neurological exam was stable for the remainder of her hospitalisation.

We did not administer systemic anticoagulation for the cavernous sinus thrombosis as we believed that the thrombosis process was infectious and inflammatory related and the thrombus would resolve with treatment of the underlying aetiology. Additionally, systemic anticoagulation was relatively contraindicated in the presence of an external ventricular drain; however, we were prepared to consider systemic heparinisation if there was evidence of thrombus propagation or her clinical condition worsened as a result of the thrombus.

Outcome and follow-up

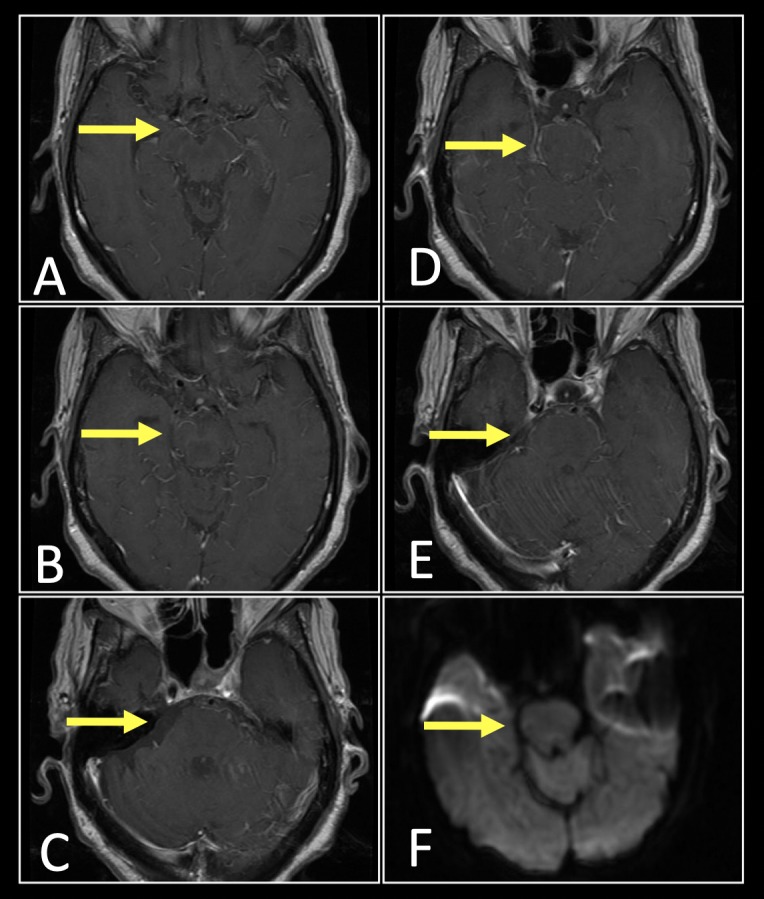

The patient underwent a total of 14 days of intraventricular antimicrobial therapy in addition to systemic antibiotics and her mentation slowly improved. By day 30 of her hospitalisation, the intraventricular therapy was discontinued and the EVD removed without complications. She made a recovery to her pre-hospital baseline and was discharged to a rehabilitation home on hospital day 35. The patient completed 3 months of outpatient oral antimicrobial therapy with oral ampicillin/sulbactam and oral metronidazole. At 3 months posthospitalisation, she had made a full neurological recovery. Follow-up MRI, MRA and MRV of the brain (figure 2) at 6 months posthospitalisation demonstrated a marked decrease in the extent of meningeal enhancement and no evidence suggestive of cavernous sinus thrombosis or abscess. At the time of publication, she remained alive without neurologic or ototoxic sequelae.

Figure 2.

Follow-up imaging of cavernous sinus meningitis after treatment with intraventricular antibiotic therapy. T1-weighted contrast enhanced MRI of the brain (A–E) revealed resolution of meningeal enhancement and associated intracranial abscess. Diffusion weighted imaging demonstrates resolution of the restricted diffusion with subtle low signal changes within the pontine tegmentum suggestive of encephalomalacia (F, arrow).

Discussion

This patient demonstrated acute on chronic sinusitis complicated by extension of her infection to the intracranial cavity. Direct extension of a sinus infection into the intracranial cavity leading to an intracranial abscess is a known sequela of complicated sinusitis.3 However, this patient’s condition was further complicated with the development of acute bacterial meningitis, an SCST and a brainstem abscess adjacent to the cavernous sinus which was in a surgically inaccessible location.

Sino-nasal infections can spread to the cavernous sinuses through multiple mechanisms: (1) haematogenously through the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins as well as through small branches from the posterior ethmoidal and sphenoidal sinuses; and (2) via direct osteomyelitic extension through the thin vulnerable posterior wall of the sphenoid bone that separates the sphenoid sinus from the cavernous sinus.4–7 The dural sinuses and the cerebral and emissary veins which share drainage with the nasal cavity are valve-less structures thereby allowing bidirectional blood flow. The valve-less structure of the veins accompanied by the vast vascular connections to the cavernous sinuses makes this region of the intracranial cavity particularly vulnerable to the formation of septic thrombosis.8 Once bacteria become haematogenously disseminated, coagulative substances and toxins released by the bacteria can stimulate the formation of a thrombus secondary to endothelial damage. Furthermore, thrombi provide a good growth medium for bacteria, with the outer layers providing a protective barrier against antibiotics, further complicating this condition and alluding to the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.6

Early diagnosis is crucial to the successful treatment of cavernous sinus infections as there exists high mortality associated with these conditions; however, clinical timing can complicate this task. Bhatia et al and Lize et al reported several different cases of SCST and noted that the latent period between the onset of symptoms of the primary infection and SCST averaged 6 days. Once the first symptoms of SCST manifested, the average time to SCST diagnosis was nearly 14 days. This latent period between symptom onset and diagnosis are vital to patient survival, given that there are lower mortality and morbidity rates for those who were initiated on antibiotics within 7 days of admission to the hospital.2

Many individuals with SCST, including our patient, present as acutely ill patients with numerous non-localising symptoms. Patients are typically critically ill and have evidence of severe complicated sinusitis with symptoms ranging from severe retro-orbital headache and high fever to cranial nerve involvement with associated diplopia and ophthalmoplegia.2 Should the treating physician recognise chemosis, periorbital swelling and/or proptosis, the suspicion for cavernous sinus thrombosis should be raised as they are the three most common findings seen in 95% such patients.6 9 Impaired ocular mobility is likely to occur due to the close proximity between the cavernous sinus and the trochlear, abducens and oculomotor nerves. Other symptoms include neck stiffness, mental status changes and neurological deficits6; all of which were manifested in our patient.

Prior to CT and MR imaging, CST was a clinical diagnosis unless the patient underwent formal diagnostic cerebral angiography. Other conditions may resemble the presentation of CST and this discrepancy makes early diagnosis of CST critical but sometimes difficult to perform; therefore, CT and MRI are necessary for the early diagnosis of intracranial complications from sinonasal disease.5 Timely imaging and treatment are critical at the earliest suspicion of a cavernous sinus infection. Furthermore, radiographic recognition of the direct signs of CST should be noted including expansion of the cavernous sinus, convex bowing of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and filling defects.2 5 6 Schuknect et al showed the average size of a thrombosed cavernous sinus to be larger (10.8 mm) than the average cavernous sinus control (8.3 mm). The same investigation showed that when compared with normal variations, size of filling defects correlates with CST, with single filling defects greater than 7 mm is suggestive of CST. Indirect signs of CST (related to venous obstruction) include dilatation of the superior ophthalmic vein, exophthalmos and increased dural enhancement.6 The most reliable imaging criteria for the diagnosis of CST is the presence of a large, single filling defect of non-fat density or signal intensity with sinus expansion.5 Detrimental sequelae of CST often arise from arterial ischaemia or venous obstruction and advances in high-resolution CT and MRI implicate cavernous carotid arterial wall inflammation as an increasingly probable source of ischaemic complications.

Primary treatment of SCST should consist of high-dose intravenous antibiotics directed at the probable source of infection, as antibiotics have undoubtedly had the greatest impact on the prognosis of developing SCST.6 If indicated, surgical drainage can be done on the primary source of infection in cases of primary sinusitis, dental infections, brain abscesses, orbital abscesses or subdural empyema.8 Anticoagulation therapy with systemic heparinisation as an adjuvant to antibiotics remains controversial, as the risk of intracranial bleeding and benefit to prevent further thrombotic proliferation need to be assessed.9–11 In a retrospective study performed by Levine et al, early heparin use was shown to have a significant reduction in morbidity.12 However, while many believe that anticoagulation therapy can help prevent propagation and future thrombotic events, it adversely raises the potential for intracranial haemorrhage.9 The lack of clinical evidence regarding the use of anticoagulation therapy in the treatment of SCST has resulted in a discrepancy about its use among treating clinicians. The decision to perform an invasive neurosurgical procedure (placement of an external ventricular drain) to deliver intraventricular antibiotics precluded the use of systemic anticoagulation due to increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage. We were prepared, however, to administer systemic heparinisation if there was evidence of thrombus propagation or if the patient’s neurological condition deteriorated as a result of the thrombus.

The use of intrathecal or intraventricular antibiotics for the treatment of complicated central nervous system (CNS) disease has been reported in the past. Ng et al recently performed a systematic review of intraventricular vancomycin for the treatment of meningitis, ventriculitis and CNS-device related infections and concluded marked clinical improvement in these conditions.13 While the optimal dosing and regimens for treating conditions with intraventricular therapy remain unclear, the use of intraventricular antibiotics in severely ill patients in whom systemic antibiotics have failed is a potential treatment option. Intraventricular therapy has a distinct advantage over intravenous therapy in that it allows treatment to directly bypass the blood-brain barrier, often a significant limitation for delivering drug therapy to the CNS. Foreign body use in the setting of infection is also considered controversial. However, given the severe critical state and radiographic disease progression in our patient and having already failed systemic antibiotic therapy, we elected to implement intraventricular therapy. Justification to place an indwelling ventricular catheter in the setting of infection was warranted on the basis of it being (1) a temporary treatment modality and (2) a salvage technique in the setting of a grave prognosis. To the best of our knowledge at the time of publication, treatment of SCST and an adjacent intracranial abscess with ventriculostomy (for the delivery of intraventricular antimicrobial therapy) has not been reported.

Significant consideration was also given to the intraventricular antimicrobial therapy of choice to treat this unique pathology. Our patient required treatment with an agent that would be effective towards both E. corrodens, a Gram-negative bacilli and S. anginosus, a Gram-positive bacilli sometimes known as Streptococcus milleri. In doing so, we also considered her sensitivities from prior blood cultures. Although gentamicin has a known profile for being neurotoxic to the vestibular and auditory system, we chose to treat with a dose of 5 mg of intraventricular gentamicin daily for 14 days given its extensive Gram-negative coverage along with effectiveness against Gram-positive organisms. We used a lower dose to initiate therapy and would have considered dose escalation or decrease depending on the patient’s clinical response. Since the time we treated our patient, a recent multicenter retrospective cohort study on intraventricular antibiotic therapy for meningitis and ventriculitis by Lewin et al suggested that daily use of gentamicin or tobramycin with a mean dose of 6.7 mg for a median duration of 6 days (a shorter course than our regiment) resulted in sterilisation of CSF cultures in 93.4% of subjects.14 The author also highlighted recent guidelines published in 2017 by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) for the use of intraventricular antibiotic therapy in healthcare-acquired ventriculitis and meningitis.15 One of the essential points by the Lewin et al is an emphasis to consider guiding intraventricular aminoglycoside therapy by CSF drug level concentrations to avoid ototoxicity, consistent with the guidelines proposed by the IDSA. However, the author noted that CSF drug level assay was not routinely performed at major institutions and should be considered in the future with aggressive salvage techniques. Prior to initiating treatment with an intraventricular aminoglycoside, we counselled the patient’s family on the significant risk of ototoxicity in treating with this antibiotic. The risk of ototoxicity should be reviewed with the patient and families when considering a similar approach. Monitoring the CSF of drug concentrations to guide treatment should also be considered.

While intraventricular treatment with a neurotoxic agent is potentially fraught with risk, the morbidity and mortality of a worsening CNS infection refractory to standard medical treatment required aggressive salvage therapy. Therefore, given our patient’s critical state along with the impending risk of death from a fulminant CNS infection, we proceeded with a novel treatment plan which included an invasive surgical approach for antibiotic delivery intraventricularly with an emphasis on close intensive care monitoring and frequent family interaction. Our patient ultimately responded well and made a full radiographic and clinical recovery from her CNS disease.

Learning points.

Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis (SCST) and associated meningitis is a severe and rare consequence of acute sinusitis with a high mortality rate.

Quick and definitive diagnosis along with early initiation of antimicrobial therapy are key to decreasing morbidity and mortality in SCST.

Recommendations for systemic anticoagulation in the setting of SCST remain unclear and extensive consideration should be discussed prior to starting therapy (including the need for any potentially invasive procedures).

If systemic intravenous antibiotics are ineffective in treating SCST, intraventricular antibiotics delivered via ventriculostomy can be considered as a salvage therapy.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Robert Conway, D.O. and Jacob Poynter from Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine with assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: JT assisted in the surgery and was in-charge of writing the manuscript. He is guarantor. MF helped to write and edit the manuscript. DT revised and finalised the manuscript. BFR was the surgeon in-charge of the case and follow-up plan of the patient. He offered revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Worrall G. Acute sinusitis. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:565–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lizé F, Verillaud B, Vironneau P, et al. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to acute bacterial sinusitis: a retrospective study of seven cases. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2015;29:e7–e12. 10.2500/ajra.2015.29.4127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patel K, Clifford DB. Bacterial brain abscess. Neurohospitalist 2014;4:196–204. 10.1177/1941874414540684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Assefa D, Dalitz E, Handrick W, et al. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis following infection of ethmoidal and maxillary sinuses: a case report. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1994;29:249–55. 10.1016/0165-5876(94)90171-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schuknecht B, Simmen D, Yüksel C, et al. Tributary venosinus occlusion and septic cavernous sinus thrombosis: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:617–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhatia K, Jones NS. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to sinusitis: are anticoagulants indicated? A review of the literature. J Laryngol Otol 2002;116:667–76. 10.1258/002221502760237920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Korathanakhun P, Petpichetchian W, Sathirapanya P, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: comparing characteristics of infective and non-infective aetiologies: a 12-year retrospective study. Postgrad Med J 2015;91:670–4. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ebright JR, Pace MT, Niazi AF. Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinuses. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2671–6. 10.1001/archinte.161.22.2671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pavlovich P, Looi A, Rootman J. Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinus: two different mechanisms. Orbit 2006;25:39–43. 10.1080/01676830500506077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Einhäupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet 1991;338:597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swaminath D, Narayanan R, Orellana-Barrios MA, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the nose complicated with cavernous sinus thrombosis. Case Rep Infect Dis 2014;2014:1–4. 10.1155/2014/914042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levine SR, Twyman RE, Gilman S. The role of anticoagulation in cavernous sinus thrombosis. Neurology 1988;38:517–22. 10.1212/WNL.38.4.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ng K, Mabasa VH, Chow I, et al. Systematic review of efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and administration of intraventricular vancomycin in adults. Neurocrit Care 2014;20:158–71. 10.1007/s12028-012-9784-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tunkel AR, Hasbun R, Bhimraj A, et al. 2017 Infectious diseases society of america’s clinical practice guidelines for healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis*. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017;64:701–6. 10.1093/cid/cix152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewin JJ, Cook AM, Gonzales C, et al. Current practices of intraventricular antibiotic therapy in the treatment of meningitis and ventriculitis: results from a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Neurocrit Care 2018. doi: 10.1007/s12028-018-0647-0 [Epub ahead of print 16 Nov 2018]. 10.1007/s12028-018-0647-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]