Abstract

New gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 enable precision genome engineering within cell lines, primary cells, and model organisms, with some formulations now entering the clinic. “Precision” applies to various aspects of gene editing, and can be tailored for each application. Here we review recent advances in four types of precision in gene editing: 1) increased DNA cutting precision (e.g., on-target:off-target nuclease specificity), 2) increased on-target knock-in of sequence variants and transgenes (e.g., increased homology-directed repair), 3) increased transcriptional control of edited genes, and 4) increased specificity in delivery to a specific cell or tissue. Design of next-generation gene and cell therapies will likely exploit a combination of these advances.

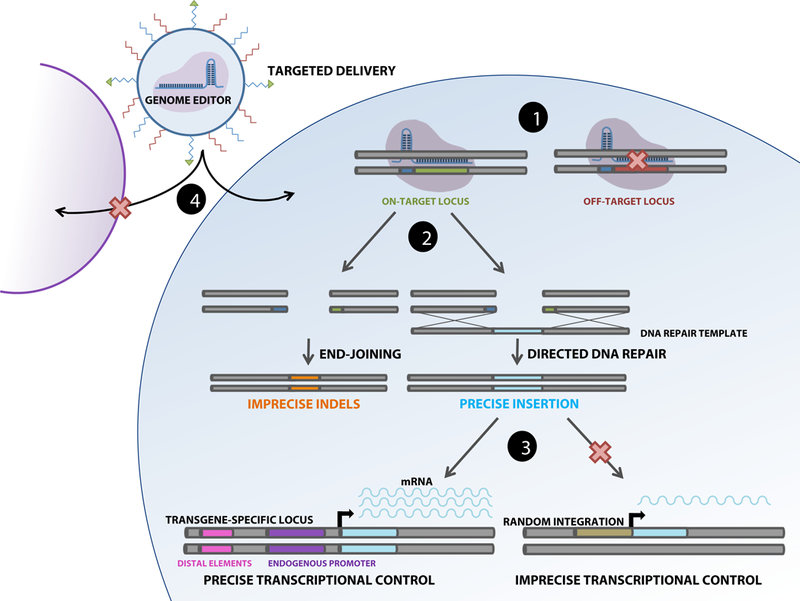

The advent of precision genome engineering has permitted staggering advances in the past decade, both as a basic tool for biological research and as a potentially transformative therapeutic agent. As the field develops, it is vital to consider what precisely is meant by “precision” engineering, and to consider a holistic approach to this paradigm. Here, we define precise genome editing in four ways: 1) editing a specific location within the genome, 2) creating scarless, definable genomic changes, 3) deliberate promoter and editing locus selection for transcriptional control, and 4) spatiotemporal specificity with regard to which cell and tissue types receive editing machinery (Figure 1). These four considerations are vital across diverse applications to ensure maximal functionality of edited sequences, while minimizing the incidence of deleterious or unnecessary mutations. As the field of clinical genome editing continues to evolve, researchers should consider each aspect of precision in their efforts to design the next generation of therapies.

Figure 1: Four types of “precision” in genome editing.

Schematic illustrates four ways in which precision genome editing can be achieved: (1) the binding of genome editing machinery to the desired target genomic locus, (2) the incorporation of the correct sequence into the edited locus following DSB formation or after base editing (not shown), (3) precise regulation of integrated transgenes by endogenous promoters and distal elements in comparison to random integration, and (4) delivery to specific cell types by engineered nanomaterials or viral capsids.

Precise on-target nuclease activity

From the inception of genome editing, researchers have been concerned with the ability to edit the genome at the target site, while limiting edits elsewhere within the genome, commonly called “off-target effects.” Shortly after CRISPR systems were identified as genome editing tools1,2, several groups raised concerns that Cas9 may create excessive undesirable mutations3–5. Varying rates of off-target events were reported ranging from >1000 per sgRNA sequence6 to negligible effects7, resulting in calls to develop better off-target screening methods. Popular techniques to quantify off-target sites include Digenome-seq, Circle-Seq, Guide-Seq, BLISS and integrase-deficient lentiviral vectors8–12.

Following these observations, many researchers adopted new methodologies to controllably introduce genome editing components, including tighter stoichiometric control that replaced plasmid-based systems with ribonucleoproteins13 (RNPs), and strategies to regulate when and where Cas9 is expressed14–16. These controlled methods showed a concurrent decrease in the number of off-target effects15, and it is likely that RNP-based editing systems will remain popular in the clinic. The timing and location of editing events can also be modulated by light and small molecules to control nuclease activity. Modified Cas9 nucleases can be selectively activated with small molecules to decrease the gene editing time window14. These ligand- dependent nucleases demonstrate 25-fold higher specificity with regards to on-target vs. off- target edits, and can also be used to induce Cas9 functionality in vivo at time-specific intervals during development. Combined, these technologies highlight the power of dynamic temporal control over genome engineering machinery.

Additional efforts to decrease off-target effects have emphasized further modifying the nuclease, including engineered “nickase” Cas9 proteins featuring only one active nuclease domain. When used alone, nickases cannot create a full double strand break (DSB). However, when two nickases are paired, the resultant break can be repaired via non-homologous endjoining (NHEJ)17. While this method lowers off-target effects, the efficiency of genome editing is greatly decreased, as two nickases and two sgRNAs need to be delivered to the nucleus to perform simultaneous cuts; furthermore, high efficiency repair of individual nicks can impede successful creation of a DSB. Thus, practical applications of nickase therapeutics may be limited. Others have engineered Cas9 RNP by mutating residues that interact with the protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) (5’-NGG-3’ in S.Pyogenes) region of the sgRNA18. These modifications expand the targeting capabilities of Cas9 to recognize PAM sites that occur less frequently throughout the genome, thereby decreasing off-target binding capability. Cas9 proteins from different species (N. Menengiti19,S. Aureus20) have a similar potential.

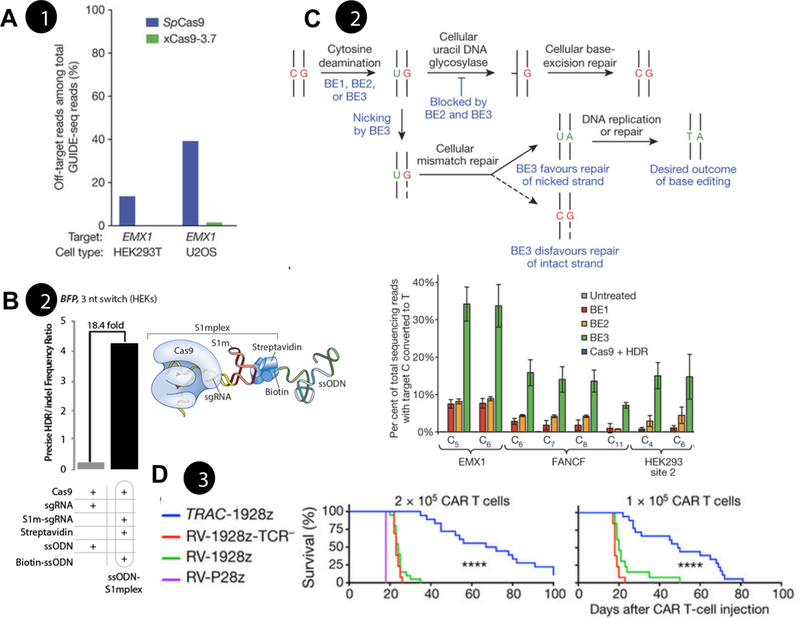

Insights into Cas9 structural biology21,22 yielded a rational design approach to create high-fidelity variants of Cas9: eSpCas923,Cas9-HF124, and xCas925 (Figure 2A). Cas9 variants function by decreasing the binding time of the sgRNA to the target sites within the genome, resulting in a decrease in off-target binding and cutting. All variants also claim to only slightly decrease the frequency of on-target DSB formation. Recent work has shown that they actually decrease off-target cuts by modifying the kinetics of the change in the structural formation26, but may also work poorly when introduced into human cells without modifications to the sgRNA27. At the moment, these high-fidelity Cas9 variants may represent a quick path to clinical relevance as they can greatly reduce off-target events.

Figure 2: Examples of increased precision with genome editing.

a) Decreasing off-target mutation through Cas9 protein engineering. xCas9 has engineered catalytic sites to recognize different PAM sites. This development led to decreased levels of off-target effects at the human EMX1 locus25. b) Increasing precise gene editing through localization of donor DNA templates. Left: Ratio of precise to imprecise editing using S1mplex. Right: S1mplex technology tethers donor ssODN to Cas9 RNP through aptamers in the sgRNA38. c) Top: Precise editing of genomic loci without DSB formation. Schematic of base editor (BE) technology, deaminase attached to Cas9 RNP is capable of creating a G>A mutation without the formation of genomic instability. Bottom: Efficiency of base editor system at three genomic loci49. d) Insertion of a Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) transgene into the human T cell receptor (TCR) alpha constant (TRAC) locus. Insertion into this locus regulated the gene via the endogenous TRAC promoter, yielding more potent CAR T cells that prolonged the survival of a leukemic mouse model54. RV: retroviral. All data pending reprint permission.

Precise scarless incorporation of new sequences

While some desired outcomes can be accomplished via error-prone DSB repair (e.g. NHEJ in Figure 1), there are still challenges that can only be solved through precise point mutations or transgene insertion via homology-directed repair (HDR), herein termed “scarless editing”. Researchers have thus attempted to increase both the overall efficiency of HDR as well as the ratio of precise to imprecise mutations.

Early work to increase scarless editing levels focused on modulating cellular DSB repair pathways. Multiple groups showed that small molecule mediators (e.g. SCR7, L755507) can increase the relative proportion of scarless editing events28,29. More recently, co-introduction of an i53 protein30 was able to increase scarless editing. These methodologies are most applicable for in vitro cell culture applications where potential toxicity is less limiting.

Building on this idea, other research demonstrated that timed delivery of gene-editing particles to certain points in the cell cycle corresponding to DNA synthesis could also increase HDR rates31. This method has been further applied by synchronizing cell cycles and subsequent timed delivery during S-phase32. Others have combined these ideas with Cas9 protein engineering methods. This technique, called Cas9-hGem, retains Cas9 protein within the cell only when HDR is favored during the cell cycle33. These methodologies hold great promise for in vitro cell culture applications, but may be untenable for in vivo editing where the majority of cells are in a post-mitotic state.

For point mutations and short knock-ins, single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) templates hold significant promise for treating disease variants due to their ease of synthesis. However, sequence changes encoded by the ssODN are infrequently incorporated after editing (<10%), and desired edits are typically outnumbered by other sequence outcomes (presumably NHEJ). Recent reports have shown that ssODN design can significantly alter how the DSB is repaired. By making ssODN homology arms asymmetrical around the cut site, HDR can be promoted up to 5-fold higher over symmetrical ssODNs34,35. However, these methods still require free-floating foreign DNA that is not necessarily available to create the desired edit at the cut site. To solve this problem, several groups have tried strategies to link the ssODN to Cas9. For example, the sgRNA and ssODN can be chemically tethered36. Other techniques have leveraged avidin/biotin binding capabilities to link the ssODN directly to the CRISPR protein37 or the sgRNA through the use of accessory proteins and RNA aptamers38 (Figure 2B). Each of these methods increase the ratio of precise edits:imprecise mutations and could potentially be delivered as a preassembled RNP for an all-in-one therapeutic.

Finally, other methods attempt to avoid the use of HDR altogether, and instead leverage other DNA repair pathways. One method that has been explored, especially in post-mitotic cells, is microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ). This pathway is thought to use small regions of homology between single strands that form via exonuclease activity during resection after the DSB. This pathway may contribute to commonly occuring indel mutations39 or small insertions40, although recent work has shown that integration of novel DNA may be possible. Several groups have developed protocols using small homology arms that undergo resection to form regions that overlap with genomic DNA41. The most well-known technology using this pathway is homology-independent targeted integration42, which requires only 8 bp of homology around the cut site to insert full transgenes in post-mitotic cells in vivo. These approaches avoid some of the challenges in assembling long homology arms into donor constructs.

In combination with donor DNA design, novel CRISPR systems have been discovered that may help precise gene correction. Cas12a (formerly Cpf1) functions similarly to Cas9 nickase but requires only one protein component to make a staggered DSB around the target site43. By creating a staggered DSB that is 17 nucleotides distal to the PAM, the PAM is less likely to be destroyed during cleavage, thus allowing for repeated DSBs. In bacteria, repeated DSBs increased the likelihood of HDR over NHEJ44 Further work has also shown that Cas12a has a lower rate of off-target effects, contributing to the precision of the nucleases45. However, following DNA cleavage, HDR can still be initiated. This increases the ratio of precise to imprecise mutations, and reduces the risk of undesired NHEJ products46. Most recently this has been shown in spinal muscular atrophy patient iPSCs47, suggesting untapped potential for precision gene correction. While Cas12a has obvious benefits for precise gene editing, it has recently been suggested to possess ssDNA cleavage activity, even in the absence of a PAM site48; thus, it may be better suited for dsDNA templates used for large transgenes.

Base editors are particularly attractive for clinical translation, as they avoid DSBs entirely. They employ a catalytically dead version of Cas9 fused to a DNA deaminase to modify existing base pairs in the sgRNA protospacer region (Figure 2C). Base editors deaminate cytidine bases to form uridine. These modified bases are then recognized by the cell as mismatched and corrected to thymidine49. Current work in this area mostly focuses on C>T (or the analogous G>A) conversions, although future versions will aim to allow modifications of any single base50.While this technology should avoid unwanted genomic instability through the breaking of DNA strands, imprecise editing can also occur, as all C nucleotides within the protospacer region are capable of being modified. Current work is addressing this shortcoming by shortening the available editing region51.

Precise transcriptional control

Expression of edited transcripts can vary over time, as well as across cell differentiation and behavior patterns. Misregulation of the edited transcript can compromise therapeutic efficacy or lead to adverse events. Therefore, it is critical to consider strategies to maximize transcriptional control of any edited transcripts, especially knock-in constructs. Various strategies target “safe harbor” loci, such as the well-characterized AAVS1 locus in humans52. However, increasing efforts are focusing on selection of more specific editing loci, and emphasizing sophisticated transcriptional control of transgene expression beyond the use of constitutive promoters.

A striking discovery regarding the necessity for precise transgene expression recently emerged in the Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cell therapy field. In the CAR T paradigm, a synthetic CAR transgene targeting a cancer-enriched antigen is knocked into the patient’s T cells ex vivo, which are then expanded and reinfused, thereby engineering the immune system to recognize and target cells bearing the antigen53. Gene transfer traditionally employs retroviral or lentiviral vectors, which raises concerns ranging from insertional oncogenesis to unregulated CAR expression levels. One group recently used CRISPR-Cas9 to generate CAR T cells featuring a transgene at the T cell receptor alpha (TRAC) locus, which simultaneously knocked out the endogenous T cell receptor (TCR) and ensured that CAR expression was regulated by the endogenous TRAC promoter54 (Figure 2D). These CAR T cells demonstrated striking results in a leukemic mouse model, and also displayed fewer biomarkers of dysfunctional CAR T cells, thus suggesting that precise transgene control may yield a more potent clinical product.

Additional recent work further underscored the importance of transcriptional considerations through a strategy to map protein binding sites for BCL11A, a regulator of fetal hemoglobin silencing which is aberrantly expressed in hemoglobinopathies such as sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia55. This study elucidated promoter-mediated repression of BCL11A in adult cells driving the switch from fetal to adult globin, and indicated that some disease variants involve disruption to cis-regulatory elements of BCL11A. These elements of the genome are significant current targets for therapeutic development for diseases involving dysregulated protein expression.

Precise editing within specific cells and tissues

While the transcriptional regulation of gene editing outcomes is a critical consideration, delivery to appropriate tissues is equally if not more important for any somatic editing approach. Precise delivery of editing components remains an extant challenge within the field, as many delivery agents suffer from low efficiency, high toxicity, and immunogenicity. Both viral and nonviral delivery agents have been engineered to achieve cell and tissue specificity.

Viral vectors are one of the most commonly used methods for delivering genetic payloads56. There is an increasing trend towards the use of adeno-associated viruses (AAV), which are capable of transducing non-mitotic cells while avoiding integration into the target genome. These vectors come in various serotypes with tropism specific to particular tissues, and have been used to edit the mammalian CNS57,58 and retina, for which a first-in-kind AAV gene therapy, Luxterna™, has received FDA approval. AAV viruses can handle genetic payloads up to 5 kb, which limits their efficacy for some constructs; however, when used with smaller nucleases such as SaCas9, this issue is somewhat mitigated20. Viral constructs can also be engineered to harbor cell and tissue-specific promoters driving expression of the gene editing system20,59, such that editing machinery is not expressed in non-desired cell types.

In spite of the relative efficiency of AAV delivery vectors, capsid immunogenicity remains a barrier. Additionally, if used to deliver the nuclease sequence along with template DNA, there are significant concerns about the effects of long-term nuclease expression within the target cell that severely dampen the potential for clinical use. Thus, nonviral delivery methods, such as nanocarriers and other customized biomaterials, are being explored to circumvent these problems. In order for gene editing components to produce therapeutic effects, they must traffic to the desired tissue without producing an immune response, enter the target cell, escape the endosome, and enter the nucleus60. This is particularly challenging in the context of nuclease delivery, as Cas9 and other proteins are sizeable and sgRNAs carry a negative charge, two characteristics that limit cell penetration61.

Several designs have demonstrated high gene-editing efficiencies when used with RNPs, ranging from 30–40% in cell lines, and up to 90% delivery efficiency13,62–64. These nanocarriers have demonstrated comparable efficiency to conventional electroporation or lipid-based reagents (e.g. Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX65), and have the potential to facilitate nuclease delivery in vivo at therapeutically active rates while remaining biocompatible in patients. To complement these nanoparticle designs, others have engineered gene-editing components themselves for improved tissue specificity. A recent paper described engineered Cas9 proteins featuring glycoprotein receptor ligands conferring specificity to liver cells66. These engineered nucleases were able to both penetrate liver cells in vitro and escape the endosome to confer organ-specific edits. While not yet validated in vivo, these findings raise the possibility for future precision editing designs featuring tissue-specific nucleases.

In addition to increasing the overall efficiency of delivery, custom biomaterials can be engineered to direct genetic payloads to specific tissue types to allow gene editing in situ, thereby bypassing many of the biomanufacturing challenges associated with ex vivo therapy design. Researchers recently developed DNA nanocarriers with the capacity to deliver CAR transgenes to T cells in a leukemic mouse model by coupling anti-CD3 ligands to polyglutamic acid (PGA)67. These nanocarriers demonstrated specificity to circulating T cells over other blood cell types shortly after delivery (34% and 6% respectively), demonstrated no immediately apparent toxicity, and caused tumor regression at rates comparable to adoptive T cell transfer. While further work is required to ensure the method’s safety, this approach represents a tantalizing possibility for off-the-shelf CAR therapies.

Complementary strategies

It is likely that advances within each of these types of precision will be complementary, ultimately enabling more precise genomic surgery within patients’ cells in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo. For in vitro applications, we envision precision drug discovery to be accelerated by enhanced tools for disease modeling, target validation and toxicological studies. Meanwhile, in ex vivo uses, we anticipate precision-engineered cell and tissue therapies that incorporate more functionality from synthetic circuits68. Finally, for in vivo somatic gene editing applications, we envision injectable viral and nanoparticle strategies that specifically edit stem cells to regenerate tissues and correct disease-causing mutations. A key challenge for translation will be to demonstrate precision through the regulatory pathway, as new tools are required to assess off- target events, the full array of sequencing outcomes and genetic variants from gene editing, aberrant expression of the edited transcript, and potential immune response. Successful strategies to overcome this challenge will pave the way for an unprecedented class of therapeutics, with curative potential for many of the world’s most pernicious and heterogeneous diseases.

Table 1.

Four types of “precision” in genome editing.

| Type of Precision | Description | Potential Tools to Improve Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting | The nuclease cuts precisely at the desired genomic locus, without producing off-target double strand breaks. |

RNP vs. plasmid13 Ligand-dependent nucleases14 Light-dependent nucleases16,69 Nickases17 Engineered PAM recognition18 High fidelity nucleases23,24 |

| Sequence | Sequence outcomes are precisely defined (typically, increased homology-directed repair vs. non-homologous end joining). |

Small molecule HDR mediators28,29 Cell cycle-timed gene editing31,32 Cas9-hGem33 Asymmetrical donor templates34,35 Tethering ssODN to Cas9 or sgRNA36–38 Cas12a/Cpf143,45,46 Base editors49–51 |

| Expression | The edited gene is expressed in a definable manner mimicking endogenous expression levels. |

Selection of precise knockin loci/promoters54 CUT&RUN mapping55 |

| Delivery | Gene edits occur precisely within the target cell or tissue. |

Targeted AAV vectors57,58 Nanocarriers13,62,64,67,70 Tissue-specific nucleases66 |

HIGHLIGHTS.

Precision can be defined with respect to targeting, sequence, expression, and/or delivery.

Cas9 and other nucleases have been engineered to decrease off-target frequency.

Precise sequence outcomes can be favored through various strategies.

Insertion of transgenes at endogenous loci promotes well-regulated expression.

New nanomaterials and vectors can help direct potential therapeutics to specific tissues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge generous financial support from the National Science Foundation (CBET- 1350178, CBET-1645123, and DGE-1747503), National Institute for Health (1R35GM119644– 01), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA-G2013 -STAR-L1), Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, and the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery. The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Acronyms:

- CRISPR

Clustered Regularly-Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats

- BLISS

Breaks Labeling In Situ and Sequencing

- RNP

Ribonucleoprotein

- NHEJ

Non-Homologous End Joining

- HDR

Homology-Directed Repair

- PAM

Protospacer-Adjacent Motif

- ssODN

Single-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotide

- DSB

Double Strand Break

- sgRNA

Single-Guide RNA

- MMEJ

Microhomology-Mediated End-Joining

- CAR

Chimeric Antigen Receptor

- CUT&RUN

Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease

- TRAC

T Cell Receptor Alpha Constant

- TCR

T Cell Receptor

- AAV

Adeno-Associated Virus

- PGA

Polyglutamic acid

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- iPSC

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell

- BE

Base Editor

- RV

Retrovirus

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

J.C-S. and K.S. have filed a patent on the S1mplex technology. K.M. declares no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jinek M et al. A Programmable Dual-RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive bacterial Immunity. Science (80-.). 337, 816–822 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mali P et al. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. 823, 823–827 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cradick TJ, Fine EJ, Antico CJ & Bao G CRISPR/Cas9 systems targeting b- globin and CCR5 genes have substantial off-target activity. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan J et al. Genome-wide identification of CRISPR/Cas9 off-targets in human genome. Nat. Publ. Gr. 24, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pattanayak V et al. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA- programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuscu C, Arslan S, Singh R, Thorpe J & Adli M Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veres A et al. Cell Stem Cell Low Incidence of Off-Target Mutations in Individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN Targeted Human Stem Cell Clones Detected by Whole- Genome Sequencing. (2014). doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D et al. Digenome-seq: Genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat. Methods (2015). doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai SQ et al. CIRCLE-seq: A highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat. Methods (2017). doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai SQ et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 187–198 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan WX et al. ARTICLE BLISS is a versatile and quantitative method for genome-wide profiling of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Commun. 8, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai T-L, Wang B, Squire MW, Guo L-W & Li W-J Endothelial cells direct human mesenchymal stem cells for osteo- and chondro-lineage differentiation through endothelin-1 and AKT signaling. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 6, 88 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuris JA et al. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein- based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 73–80 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis KM, Pattanayak V, Thompson DB, Zuris JA & Liu DR Small molecule- triggered Cas9 protein with improved genome-editing specificity. Nat. Chem. Biol. (2015). doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Yanhao, Liu Xiaojian, Zhang Yongxian, Wang HA Self-restricted CRISPR System to Reduce Off-target Effects. 24, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemphill J, Borchardt EK, Brown K, Asokan A & Deiters A Optical Control of CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing. doi: 10.1021/ja512664v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ran FA et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinstiver BP et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. doi: 10.1038/nature14592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou Z et al. Efficient genome engineering in human pluripotent stem cells using Cas9 from Neisseria meningitidis. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313587110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ran FA et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. doi: 10.1038/nature14299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimasu H et al. Crystal Structure of Cas9 in Complex with Guide RNA and Target DNA. Cell 156, 935–949 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anders C, Niewoehner O, Duerst A & Jinek M Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 513, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.**Slaymaker IM et al. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 351, 84–8 (2016).Engineered Cas9 protein that reduced off-target activity while maintaining on-target efficiency.

- 24.**Kleinstiver BP et al. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases enable highly efficient genome editing in a wide variety of organisms Alteration of SpCas9 DNA contacts. Nature 529, (2016).Engineered Cas9 protein that lost nearly all off-target activity while maintaining on-target effectiveness.

- 25.**Hu JH et al. Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nat. Publ. Gr. 556, (2018).Developed the xCas9 variant to recognize different PAM sites, decreasing off-target effects at the human EMX1 locus.

- 26.Singh D, Sternberg SH, Fei J, Ha T & Doudna JA Real-time observation of DNA recognition and rejection by the RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. bioRxiv 7, 048371 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim S, Bae T, Hwang J & Kim J-S Rescue of high-specificity Cas9 variants using sgRNAs with matched 5’ nucleotides. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1355-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu VT et al. Increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair for CrIsPr-Cas9- induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu C et al. Small molecules enhance crispr genome editing in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 16, 142–147 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canny MD et al. Inhibition of 53BP1 favors homology-dependent DNA repair and increases CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing efficiency. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 95–102 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang D et al. Enrichment of G2/M cell cycle phase in human pluripotent stem cells enhances HDR-mediated gene repair with customizable endonucleases. Nat. Publ. Gr. (2016). doi: 10.1038/srep21264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S, Staahl BT, Alla RK & Doudna JA Enhanced homology-directed human genome engineering by controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. Elife 3, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutschner T, Haemmerle M, Genovese G, Draetta GF & Chin L Post-translational Regulation of Cas9 during G1 Enhances Homology-Directed Repair. CellReports 14, 1555–1566 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson CD, Ray GJ, Dewitt MA, Curie GL & Corn JE Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang X, Potter J, Kumar S, Ravinder N & Chesnut JD Enhanced CRISPR/Cas9- mediated precise genome editing by improved design and delivery of gRNA, Cas9 nuclease, and donor DNA. J. Biotechnol. 241, 136–146 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee K et al. Synthetically modified guide RNA and donor DNA are a versatile platform for CRISPR-Cas9 engineering. Elife 6, e25312 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma M et al. LETTER TO THE EDITOR Efficient generation of mice carrying homozygous double-floxp alleles using the Cas9-Avidin/Biotin-donor DNA system . Nat. Publ. Gr. 27, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.**Carlson-Stevermer J et al. Assembly of CRISPR ribonucleoproteins with biotinylated oligonucleotides via an RNA aptamer for precise gene editing. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01875-9Tethering of donor DNA to RNP increased the ratio of HDR:NHEJ events.

- 39.Bae S, Kweon J, Kim HS & Kim JS Microhomology-based choice of Cas9 nuclease target sites. Nature Methods (2014). doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemos BR et al. CRISPR/Cas9 cleavages in budding yeast reveal templated insertions and strand-specific insertion/deletion profiles. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716855115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao X et al. Homology-mediated end joining-based targeted integration using CRISPR/Cas9. Nat. Publ. Gr. 27, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki K et al. In vivo genome editing via CRISPR/Cas9 mediated homology- independent targeted integration. Nature 540, 144–149 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zetsche B et al. Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System Cpf1 is a RNA-guided DNA nuclease that provides immunity in bacteria and can be adapted for genome editing in mammalian cells. Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System. Cell 163, 759–771 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ungerer J & Pakrasi HB Cpf1 Is A Versatile Tool for CRISPR Genome Editing Across Diverse Species of Cyanobacteria. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim D et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno-Mateos MA et al. CRISPR-Cpf1 mediates efficient homology-directed repair and temperature-controlled genome editing. Antonio J. Giraldez 679, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou M et al. Seamless Genetic Conversion of SMN2 to SMN1 via CRISPR/Cpf1 and Single-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotides in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Patient-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Hum. Gene Ther. hum.2017.255 (2018). doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li SY et al. CRISPR-Cas12a has both cis- and trans-cleavage activities on single- stranded DNA. Cell Res. 1–3 (2018). doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0022-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.**Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA & Liu DR Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533, 420–424 (2016).Developed engineered Cas9 proteins capable of creating single nucleotide variations without the formation of DSBs.

- 50.Gaudelli NM et al. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bill Kim Y et al. Increasing the genome-targeting scope and precision of base editing with engineered Cas9-cytidine deaminase fusions. Nat. Publ. Gr. 35, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lyu C et al. Targeted genome engineering in human induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with hemophilia B using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 9, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piscopo NJ et al. Bioengineering Solutions for Manufacturing Challenges in CAR T Cells. doi: 10.1002/biot.201700095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.**Eyquem J et al. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature 543, 113–117 (2017).Integration of a chimeric antigen receptor transgene into the endogenous T cell receptor locus led to a more potent product than retrovirally-produced CAR T cells.

- 55.Liu N et al. Direct Promoter Repression by BCL11A Controls the Fetal to Adult Hemoglobin Switch. Cell 173, 430–442 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gori JL et al. Delivery and Specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing Technologies for Human Gene Therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 26, 443–451 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishiyama J, Mikuni T & Yasuda R Virus-Mediated Genome Editing via Homology- Directed Repair in Mitotic and Postmitotic Cells in Mammalian Brain. Neuron 96, 755–768.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaj T et al. In vivo genome editing improves motor function and extends survival in a mouse model of ALS. Sci. Adv. 3, eaar3952 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swiech L et al. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. (2014). doi: 10.1038/nbt.3055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yin H, Kauffman KJ & Anderson DG Delivery technologies for genome editing. Nat. Rev. DrugDiscov. 16, 387–399 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glass Z, Lee M, Li Y & Xu Q Engineering the Delivery System for CRISPR-Based Genome Editing. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 173–185 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alsaiari SK et al. Endosomal Escape and Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing Machinery Enabled by Nanoscale Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b11754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mout R et al. Direct Cytosolic Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9- Ribonucleoprotein for Efficient Gene Editing. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b07600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun W et al. Drug Delivery Hot Paper Self-Assembled DNANanoclews for the Efficient Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Editing. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu Xiquan, Liang Huimin, Xie Shantanu, Kumar Namritha, Ravinder Jason, Potter Xavier de, Mollerat du, Jeu Jonathan, Chesnut XD. Improved delivery of Cas9 protein/gRNA complexes using lipofectamine CRISPRMAX. Biotechnol. Lett. 38, (2064). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rouet R et al. Receptor-Mediated Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 Endonuclease for Cell Type Specific Gene Editing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. jacs. 8b01551 (2018). doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b01551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.**Smith TT et al. In situ programming of leukaemia-specific T cells using synthetic DNA nanocarriers Designing nanocarriers to achieve CAR expression in T cells. (2017). doi: 10.1038/NNANO.2017.57In situ nanoparticle delivery of gene editing components efficiently produced CAR T cells, raising the possibility of an off-the-shelf CAR T cell therapy.

- 68.Weinberg BH et al. Large-scale design of robust genetic circuits with multiple inputs and outputs for mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nihongaki Y, Kawano F, Nakajima T & Sato M Photoactivatable CRISPR-Cas9 for optogenetic genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mout R et al. Direct Cytosolic Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9-Ribonucleoprotein for Efficient Gene Editing. ACS Nano 11, 2452–2458 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]